Articles

Duterte in The Hague

Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte gained international notoriety with his violent ‘war on drugs’ – a campaign of violence targeting the country’s poor that claimed thousands of lives. He is now in a cell in The Hague, awaiting trial at the International Criminal Court, but it remains to be seen what will happen in the Philippines.

Charles Bettelheim and the Value-Form: The Problem of the Real Socialisation of the Productive Forces in Socialist Transition

The reintroduction of the question of democratic planning into contemporary Marxist debates has rested on two conjunctural factors. First, the multiple crises defining our current moment make a socialist transition, if not an inevitability, then certainly a necessity if we are to counter the tendential death drives of contemporary capitalism. Second, the qualitative leap in the productive forces – especially data-driven computational technologies – are seen, by some, as addressing the technical and logistical questions raised by prior iterations of the calculation debate: primarily the complexity of real-time, global-scale resource allocation and incentive mechanisms. These technologies, particularly data-driven tools and adaptive machine learning are said to hold potential – if oriented towards socialist aims – to manage the scale and complexity of resource allocation effectively.

Empire Unmasked: Struggles for Gender and Sexual Freedom in an Era of US Imperial Crisis

US power has organised the expanded reproduction of global capitalism over the past 70 years and continues to do so. Much ink is currently being spilled over its decline. Commentators are debating whether US decline is inevitable or overstated, whether it is proceeding rapidly or steadily, or, indeed, whether it is in decline at all. In this blog post, I want to think about US dominance not in these quantitative terms, but, rather, venture an assessment about its changing character. I will first outline how I understand the term ‘US empire’. Second, I will offer some speculative remarks about the current directionality of US empire amid generalised capitalist crisis. And, third, I will reflect on how radical struggles for gender and sexual freedom have historically taken shape in relation to the character of US empire, and what that means for queer and trans struggles today.

MEGA (From the Historical-Critical Dictionary of Marxism)

Translation of the entry ‘MEGA’ in the Historical-Critical Dictionary of Marxism (Historisch-Kritisches Wörterbuch des Marxismus [HKWM]), vol. 9/I (Hamburg: Argument, 2018), pp. 388-404. Part I written by Rolf Hecker, Manfred Neuhaus, Richard Sperl, and part II by Hu Xiaochen.

Greece: the mass rallies for justice and truth, the irreversible crisis of legitimacy and the “new that cannot yet be born”

On the 28 February, Greece experienced its biggest day of mass protest in many years. During a general strike with mass participation, large gatherings where organised in every city and town in Greece, along with protests in almost every city abroad with a Greek community. In Athens alone, it was a giant demonstration, with the estimates ranging from 400,000 to 800,000 persons attending, and everyone agreeing this was perhaps the biggest demonstration ever organised. This followed, another day of protest, on the Sunday 26 January, when the demonstrations organised all over Greece were the biggest since the 2010s.

Retotalising Capitalism: A Very Short Introduction to its History

I’ve divided this presentation into four distinct parts.[1] A shorthand description of these might be

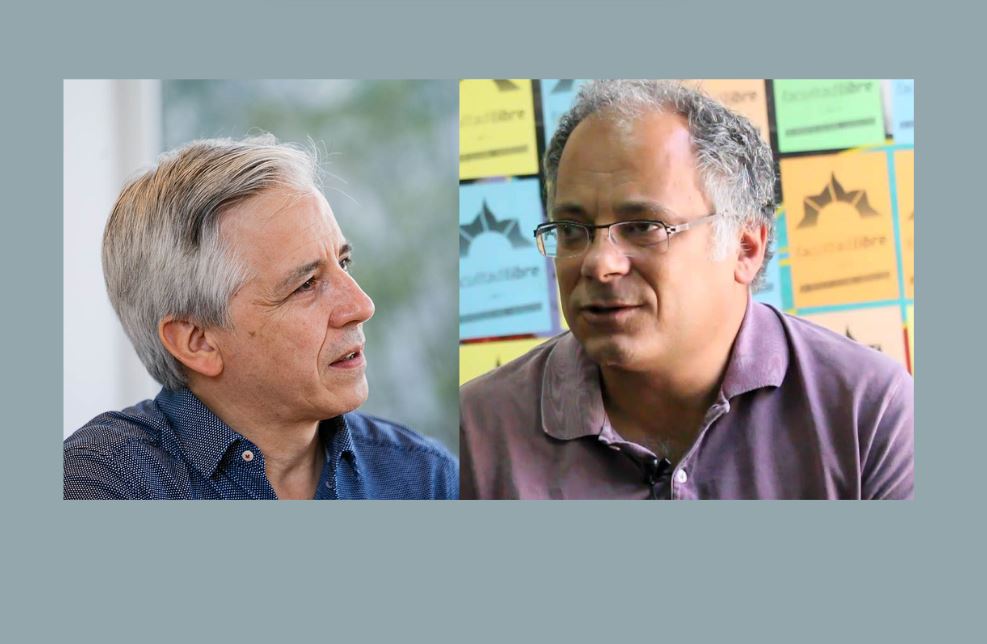

State, Counter-power and Post-fascism: from Poulantzas to the Present – Interview with Álvaro García Linera and Sandro Mezzadra

This is the text of a discussion of Álvaro García Linera and Sandro Mezzadra, responding to questions by Matteo Polleri. In this dialogue, Álvaro García Linera and Sandro Mezzadra discuss the relevance and irrelevance of Nicos Poulantzas’s thought. After tracing the role played by Poulantzas’s theory of the State in their respective works, the conversation turns to its potential uses in the present. The conversation touches on a number of key issues for the critical analysis of contemporary capitalism, such as recent changes in the global economy and the international scene, the rise of the far right and the possible horizons of a post-capitalist transition.

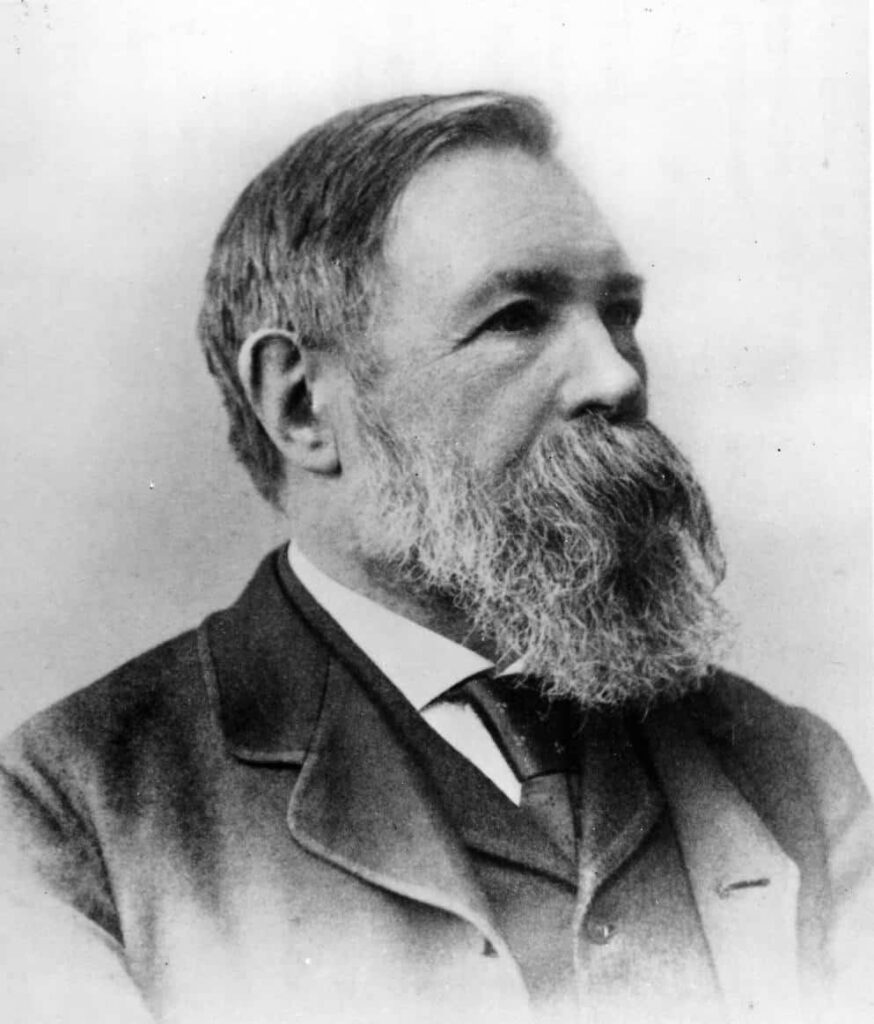

Do Marx – and Engels – have something to say on the national question (and internationalism)?

Let me start with some explanations concerning the title of my paper.[1] There is a commonly shared opinion on the relation between the “founding fathers” of historical materialism and the nation. Shared by non- or anti-Marxists and by most Marxists alike, this claims that Marx and Engels have little to say on the subject. “Little” does not mean here quantitatively little, since it is acknowledged that their writings include lengthy discussions of those “national questions” that were of primary importance at their time – Poland, Italy, Ireland, German unity, the “Eastern question”, colonial expansion, to name just the most prominent ones. The claim is, rather, that, in all those texts, there is little, if anything, that is properly original and specific, that is, integrated to their broader theoretical framework.

Lenin’s Alternative: Dual Power and a Politics of Another Type

The following essay is a revised and expanded version of the author’s online intervention entitled “Lenin’s Alternative: A Politics of Another Type”, which took place on 25 May 2024, as the closing address of the international series of events Leninist Days/Jornadas leninistas (27 January to 25 to May 2024), organised in commemoration of the centenary of the death of Vladimir I. Lenin.

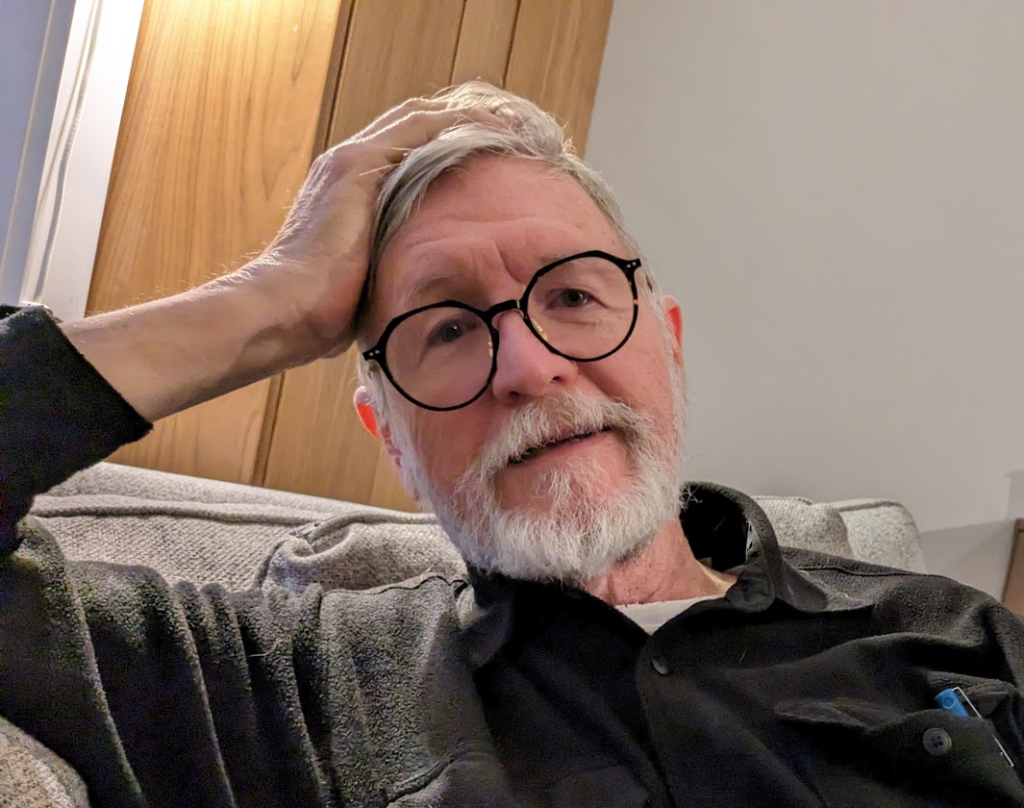

Dan La Botz: The Intellectual Autobiography of an American Leftist

I am almost eighty, an age when one begins to think about what one has done, what one has accomplished in life. So, I have been looking back on my forty-year career as a writer about labour and social movements. During this time, I have written principally about the importance of democracy in the labour movements, in society and in politics. I have written about ordinary working people’s attempts to take control over their workplaces, their labour unions, and of the political parties in which they became involved or created. I explore how ordinary people often ran into the power of the bureaucracies of unions, parties or the state, whether in the United States, Mexico, Nicaragua, or Indonesia, bureaucracies that frustrated their desire for control of their own lives.