Articles

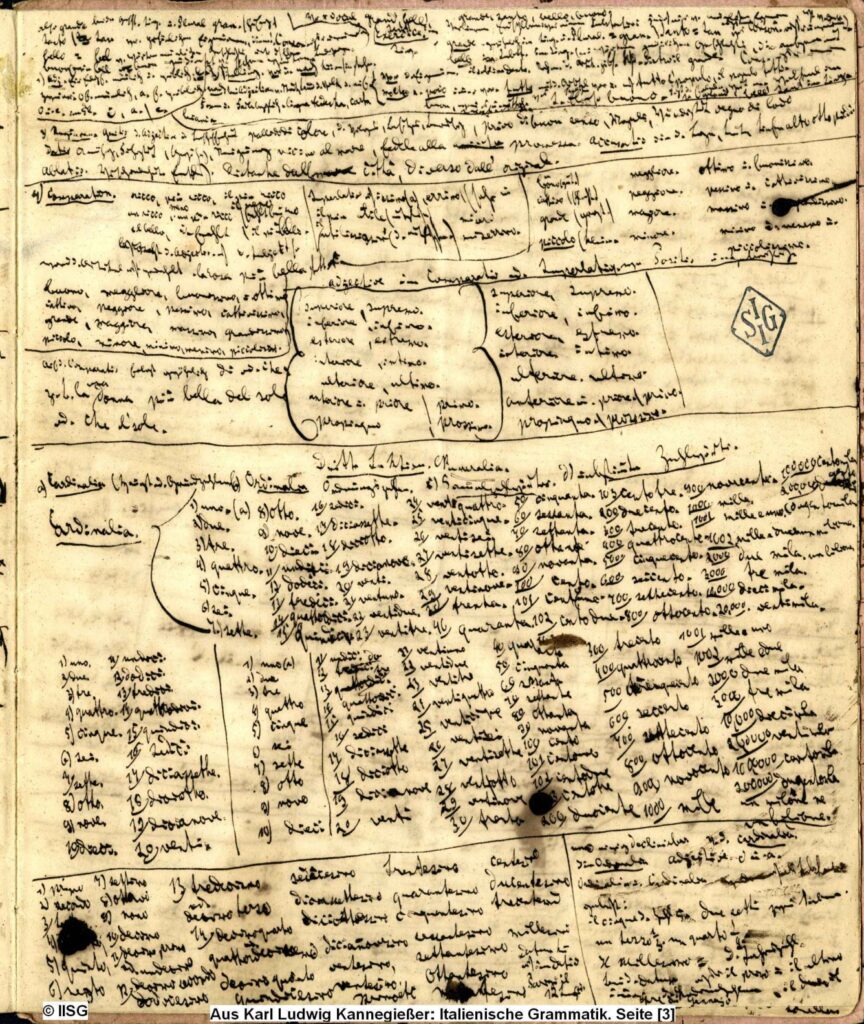

Marx and Engels as Polyglots

Karl Marx’s 1852 work The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte opens with the famous remark that men ‘make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please.’[1] He goes on to argue that whatever happens in the present time arises from and is a reaction to a political past. Recollecting and interpreting the past for present purposes requires a language. Such a language is not naturally given but needs to be socially constructed. What is more, its vocabulary and grammar stem from linguistic legacies of past ideologies. Marx draws in this regard an analogy, comparing acquisition of a political language with mastering a natural language:

Strains in a Revolutionary Leadership: Dobbs-Cannon Tensions in the US Socialist Workers’ Party

[This article is based on an unpublished manuscript by Farrell Dobbs, his Schematic on Party History.[1] Quotations from the Schematic begin each section of the article.]

Gender and/in the nation: Converging and diverging discourses

Recently, the High Court in England ruled that only those deemed biological females are legally recognised as women. In Hungary, gender identity recognition has been effectively abolished. In the US, illegalisation of abortions and attacks on the LGBTQI+ community are intensifying, under the auspices of religious groups. Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention dates back almost four years. Recently, the Greek Prime Minister declared that there are only two genders, as biology dictates.

Critical Apologetics: On Rainer Forst’s Noumenal Power

Jurgen Habermas, Rainer Forst, Nicole Deitelhoff, and Klaus Gunther signed on 16 November 2023, ‘Principles of Solidarity: A Statement’,[1] in which they clarified that the role of critical theory today was to be clear on not attributing genocidal intentions to Isreal’s actions against the Palestinian people, who are referred to in the statement as ‘the Palestinian Population’. According to this statement, the primary concern of the representatives of the Frankfurt School today is to refine ‘the standards of judgement’ and defend the ethos of the Federal Republic of Germany that is based on the obligation to ‘respect human dignity’ and protect primarily Jewish life and Isreal’s unquestionable right to exist as a Jewish state. There is no other mention of the Palestinian people in the statement, the sole and primary task of critical theory today, according to its signatories is to fend off the return of antisemitism. They single out 7 October as an event that has no historical narrative of its own beyond that of German politics of memorialisation and reconciliation – as though 7 October was an attack against Germany and Europe, and not against an ongoing colonial occupation. The signatories also effectively equivocate antisemitism with anti-Zionism. This issue is not the focus of my essay here, I can point the reader to numerous recent critical engagements such as Historical Materialism’s special issues on the topic. Rather, I am concerned with the claim that the task of critical theory is to point out the ‘standards of judgement’. This cannot be farther from Marx’s critical contribution to the analysis of modern society and its contradictions. Critical theory must not be allowed to descend into the task of safeguarding the normative liberal order and the defence of a fictive public sphere bereft of ideologies, for this definition of the task of critical theory is one step away from bourgeois moral philosophy.

The Everyday Causes and Contradictions of Trumpism

The first few months of Donald Trump’s return to the presidency have been dizzying and unsettling. From the attacks on public servants, universities, and students to the almost daily announcement of new tariffs and the slashing of a great many Federal programmes, it is difficult to just keep up with the latest news let alone to make sense of it and understand the broader context and implications of what is happening. Although most focus on the Trump regime’s increasingly authoritarian tactics and his xenophobia and imperial rhetoric, usually comparing it to past anti-democratic and fascist moments, what is often ignored is how deeper transformations of capitalism and our everyday lives may serve as the material conditions that made Trump’s political tenor and success

Duterte in The Hague

Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte gained international notoriety with his violent ‘war on drugs’ – a campaign of violence targeting the country’s poor that claimed thousands of lives. He is now in a cell in The Hague, awaiting trial at the International Criminal Court, but it remains to be seen what will happen in the Philippines.

Charles Bettelheim and the Value-Form: The Problem of the Real Socialisation of the Productive Forces in Socialist Transition

The reintroduction of the question of democratic planning into contemporary Marxist debates has rested on two conjunctural factors. First, the multiple crises defining our current moment make a socialist transition, if not an inevitability, then certainly a necessity if we are to counter the tendential death drives of contemporary capitalism. Second, the qualitative leap in the productive forces – especially data-driven computational technologies – are seen, by some, as addressing the technical and logistical questions raised by prior iterations of the calculation debate: primarily the complexity of real-time, global-scale resource allocation and incentive mechanisms. These technologies, particularly data-driven tools and adaptive machine learning are said to hold potential – if oriented towards socialist aims – to manage the scale and complexity of resource allocation effectively.

Empire Unmasked: Struggles for Gender and Sexual Freedom in an Era of US Imperial Crisis

US power has organised the expanded reproduction of global capitalism over the past 70 years and continues to do so. Much ink is currently being spilled over its decline. Commentators are debating whether US decline is inevitable or overstated, whether it is proceeding rapidly or steadily, or, indeed, whether it is in decline at all. In this blog post, I want to think about US dominance not in these quantitative terms, but, rather, venture an assessment about its changing character. I will first outline how I understand the term ‘US empire’. Second, I will offer some speculative remarks about the current directionality of US empire amid generalised capitalist crisis. And, third, I will reflect on how radical struggles for gender and sexual freedom have historically taken shape in relation to the character of US empire, and what that means for queer and trans struggles today.

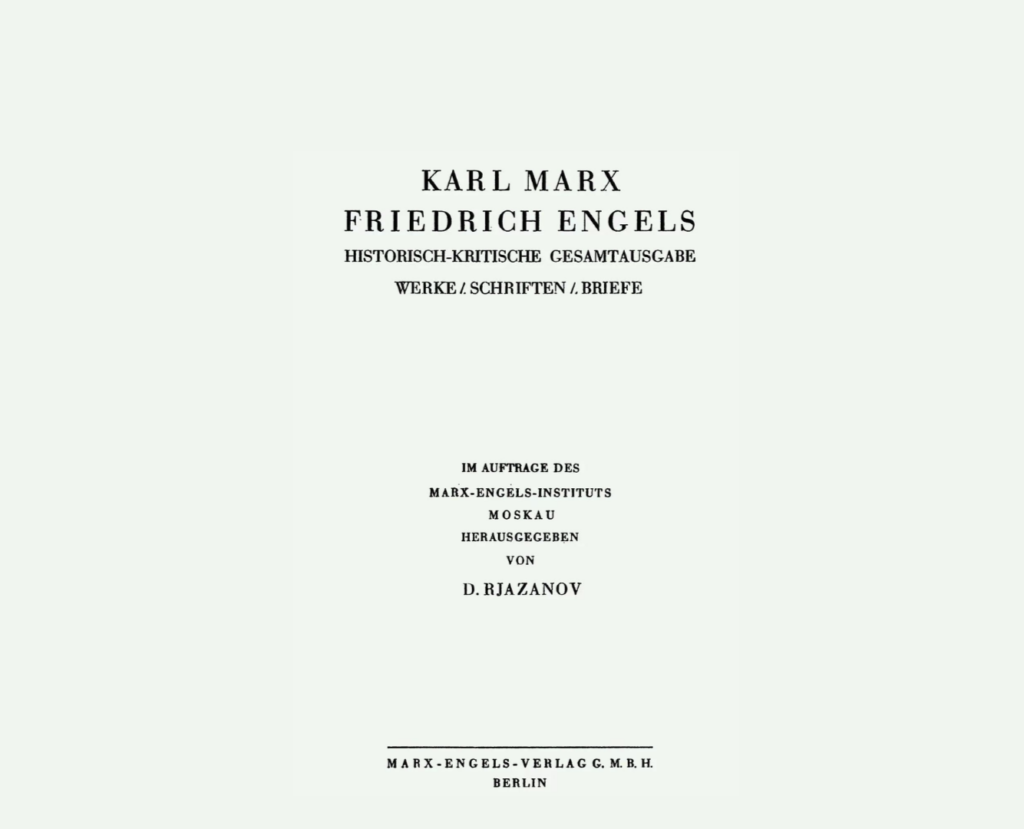

MEGA (From the Historical-Critical Dictionary of Marxism)

Translation of the entry ‘MEGA’ in the Historical-Critical Dictionary of Marxism (Historisch-Kritisches Wörterbuch des Marxismus [HKWM]), vol. 9/I (Hamburg: Argument, 2018), pp. 388-404. Part I written by Rolf Hecker, Manfred Neuhaus, Richard Sperl, and part II by Hu Xiaochen.

Greece: the mass rallies for justice and truth, the irreversible crisis of legitimacy and the “new that cannot yet be born”

On the 28 February, Greece experienced its biggest day of mass protest in many years. During a general strike with mass participation, large gatherings where organised in every city and town in Greece, along with protests in almost every city abroad with a Greek community. In Athens alone, it was a giant demonstration, with the estimates ranging from 400,000 to 800,000 persons attending, and everyone agreeing this was perhaps the biggest demonstration ever organised. This followed, another day of protest, on the Sunday 26 January, when the demonstrations organised all over Greece were the biggest since the 2010s.

Retotalising Capitalism: A Very Short Introduction to its History

I’ve divided this presentation into four distinct parts.[1] A shorthand description of these might be

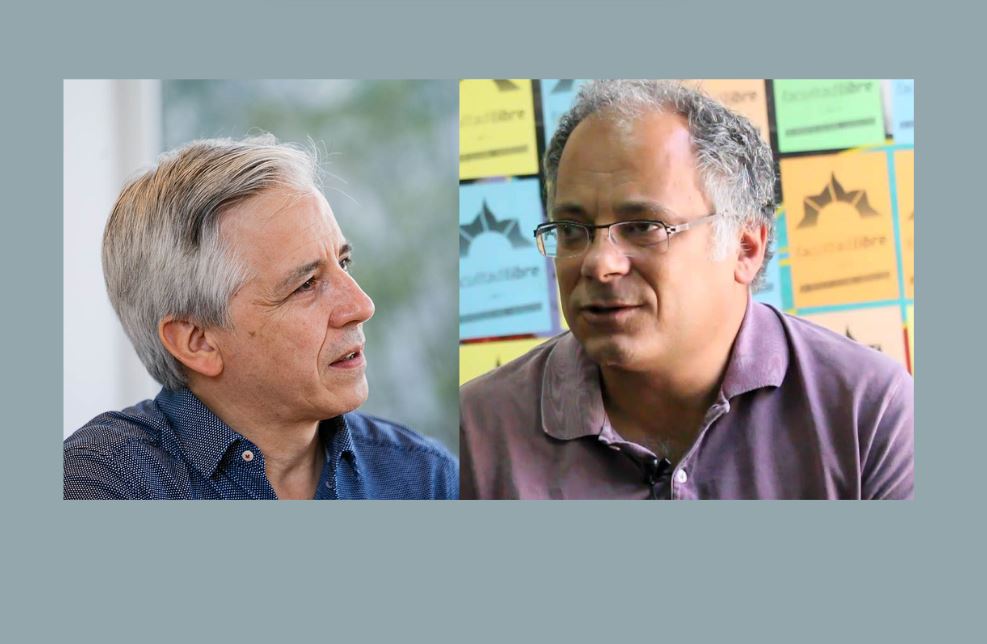

State, Counter-power and Post-fascism: from Poulantzas to the Present – Interview with Álvaro García Linera and Sandro Mezzadra

This is the text of a discussion of Álvaro García Linera and Sandro Mezzadra, responding to questions by Matteo Polleri. In this dialogue, Álvaro García Linera and Sandro Mezzadra discuss the relevance and irrelevance of Nicos Poulantzas’s thought. After tracing the role played by Poulantzas’s theory of the State in their respective works, the conversation turns to its potential uses in the present. The conversation touches on a number of key issues for the critical analysis of contemporary capitalism, such as recent changes in the global economy and the international scene, the rise of the far right and the possible horizons of a post-capitalist transition.