Figures

Unsentimental and resolute

By Georg Fülberth and translated by Gregor Benton [i]

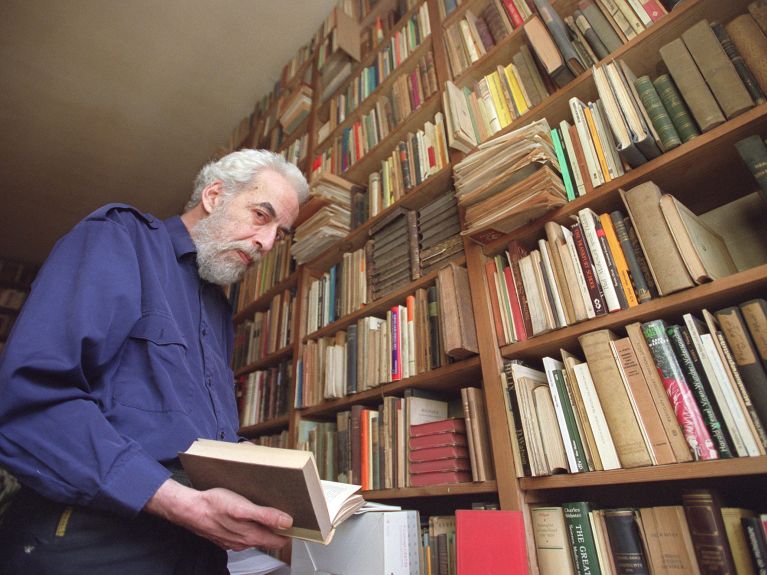

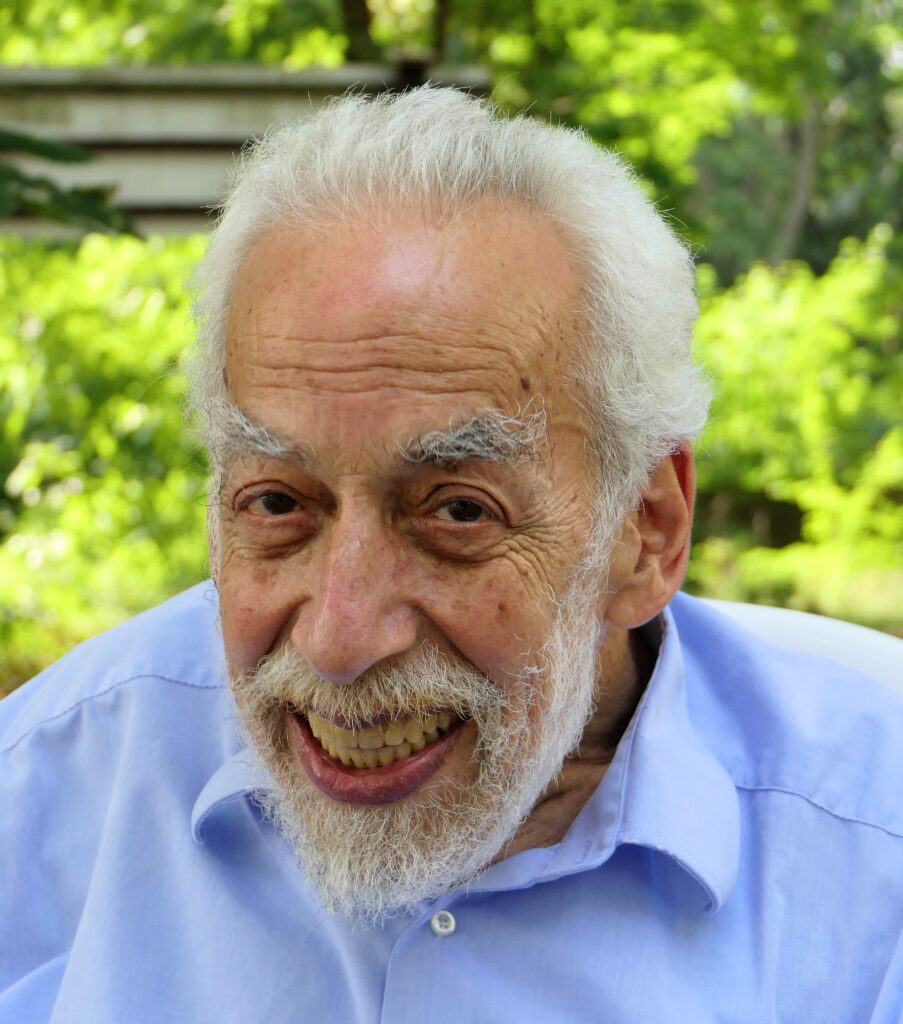

Otto Karl Werckmeister 1934-2023

“Marx’s theory of society and history was obviously not devised in order to provide a more adequate understanding of culture. It was meant to be an instrument of political practice.” (1982)

Irma Rothbart-Sinkó (1896-1967)

By Stefan Gužvica

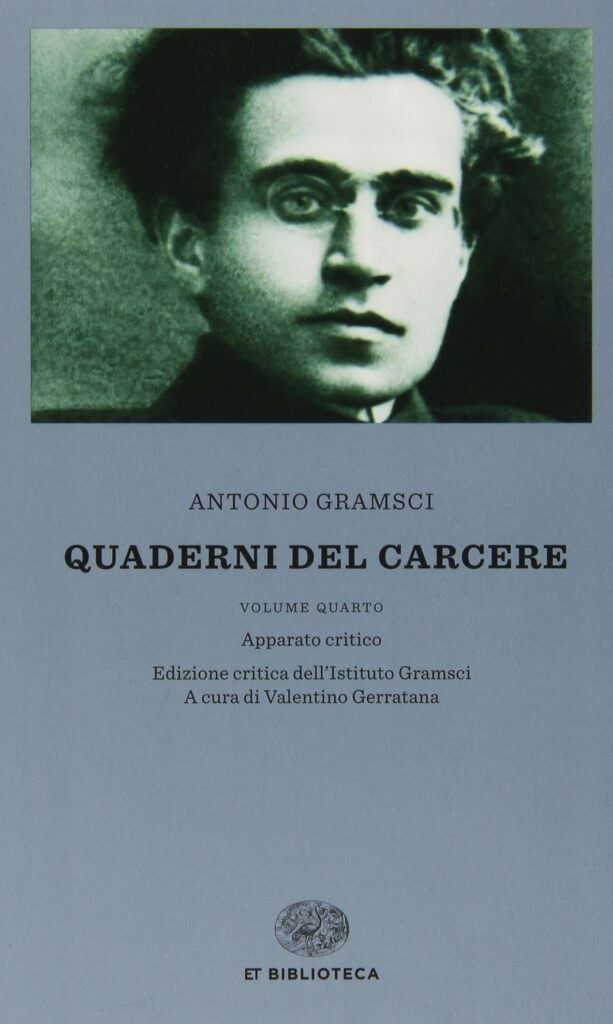

Gramsci, Sartre and the Fordist machine

The brilliant essay which makes up prison notebook 22, viz. ‘Americanism and Fordism’, was written by Gramsci in 1934, five whole years before Agnelli started FIAT’s giant Mirafiori complex near Turin, where Fordist methods were first used in a big way. The shortcoming of Gramsci’s otherwise remarkable notes is that he never gets round to the issue of how the new levels of automation associated with mass production (conveyor systems, semi-automatic machines, etc.) were transforming the nature of skills and affecting workers’ experience of work.

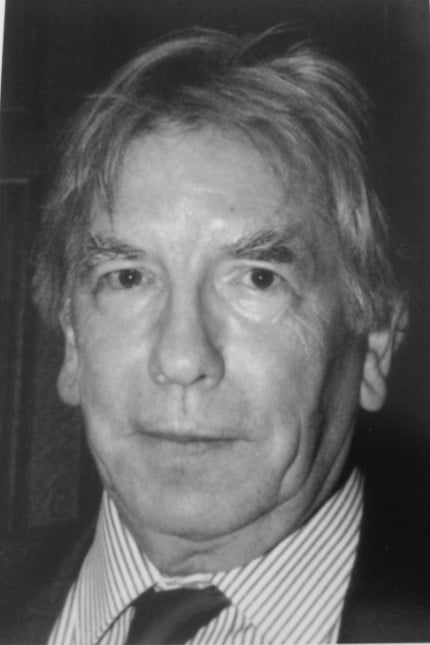

Fergus Millar (1935–2019)

Fergus Millar (1935–2019), Camden Professor of Ancient History at Oxford from 1984 until his retirement in 2002, who died a little over 2 years back. His scholarship was prodigious, but just as important, he was a remarkably kind, unassuming person (not an iota of self-importance!) who would go out of his way to be welcoming to new graduates in the Classics Faculty, as I know from my vivid memory of a reception (in Michaelmas 1987) where Fergus appeared affably out of nowhere to rescue a couple that must have looked pretty lost.

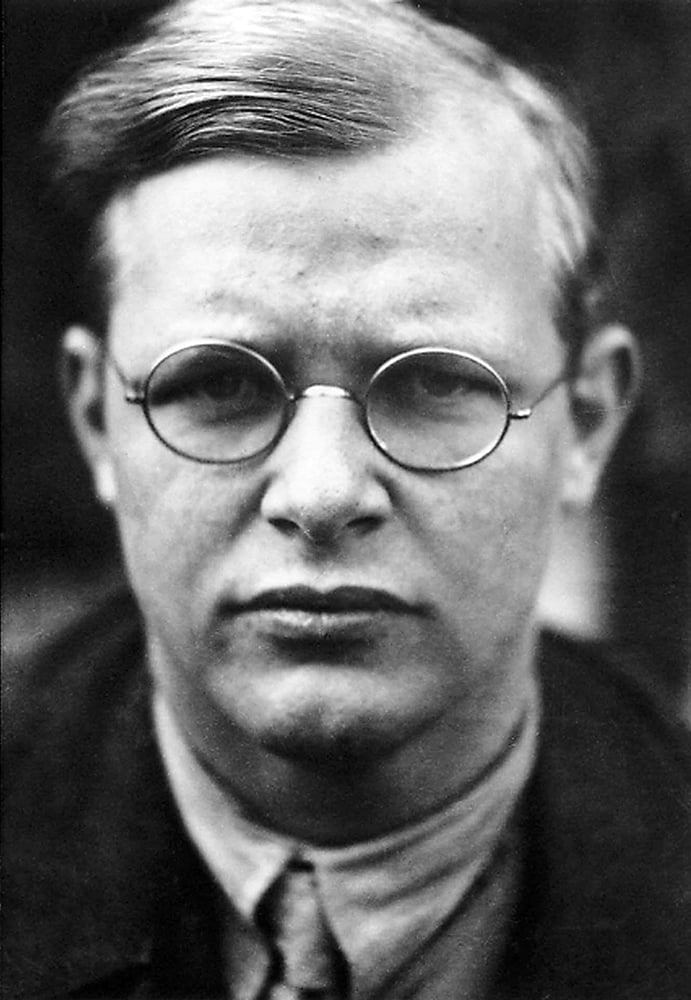

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945)

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945), the great German theologian who was executed by the Nazis in 1945. He was arrested by the Gestapo in April 1943 and hanged exactly two years later (at Flossenbürg concentration camp), accused of associating with the group that conspired to assassinate Hitler in July 1944. Tragically, his execution took place just three weeks before Hitler killed himself.

Webs of complicity: Reading Moravia’s The Conformist in India today

Italian literature and cinema have explored the issue of fascism in more subtle and fascinating ways than most comparable traditions elsewhere in Europe. In Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970), Elio Petri’s brilliant political thriller about a police commissioner who murders his lover in cold blood, then deliberately leaves clues at the scene of the crime to demonstrate his own untouchability by the law, Petri gave us a theory of the state in its most lucid and penetrating form, set against the background of the political turmoil in Italy in the late sixties.

Leopoldina Fortunati

Marx writes, ‘Only labour which produces capital is productive labour’. So what do we say about women who work at home (so-called ‘housewives’) whose labour produces/reproduces the male worker who in turn produces capital? Do they produce capital? In a crucially important passage at p. 274 of volume 1 of Capital Marx offers two radically different definitions of the ‘value of labour-power’, the first in terms of the living labour objectified in the commodity labour-power, the second in terms of the value of the means of subsistence necessary for the maintenance of the worker. It was the latter definition that became standard, viz. the conception of the value of labour-power as a basket of wage goods.

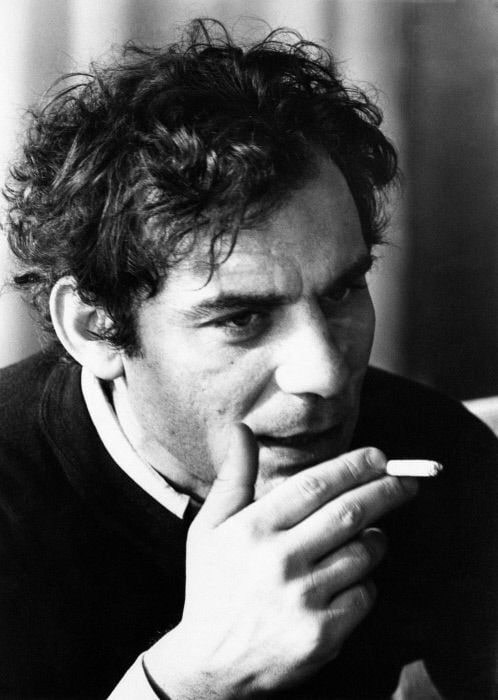

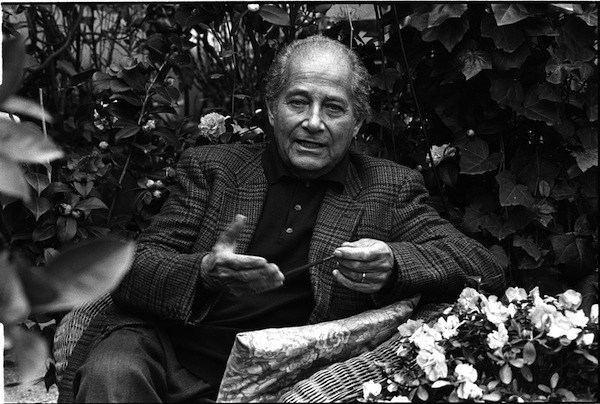

Gillo Pontecorvo (1919–2006)

Gillo Pontecorvo (1919–2006), whose masterpiece “The Battle of Algiers” (1966) remains the most perfect example of a ‘reconstructed realism’, the purest cinematic equivalent of Marx’s famous metaphor of the ‘life of the subject-matter’ being ‘ideally reflected as in a mirror’ (1873 Afterword to Capital, vol. 1). What Pontecorvo set out to do was, in his words, ‘represent the irreversibility of a revolutionary process when a colonized people acquires consciousness of its identity as a nation’. And he did this so well that the film was boycotted by the French delegation at the Venice Film Festival in 1966 and banned for over three years in both France and England (till 1971).