By Karen Vesper and translated by Gregor Benton[1]

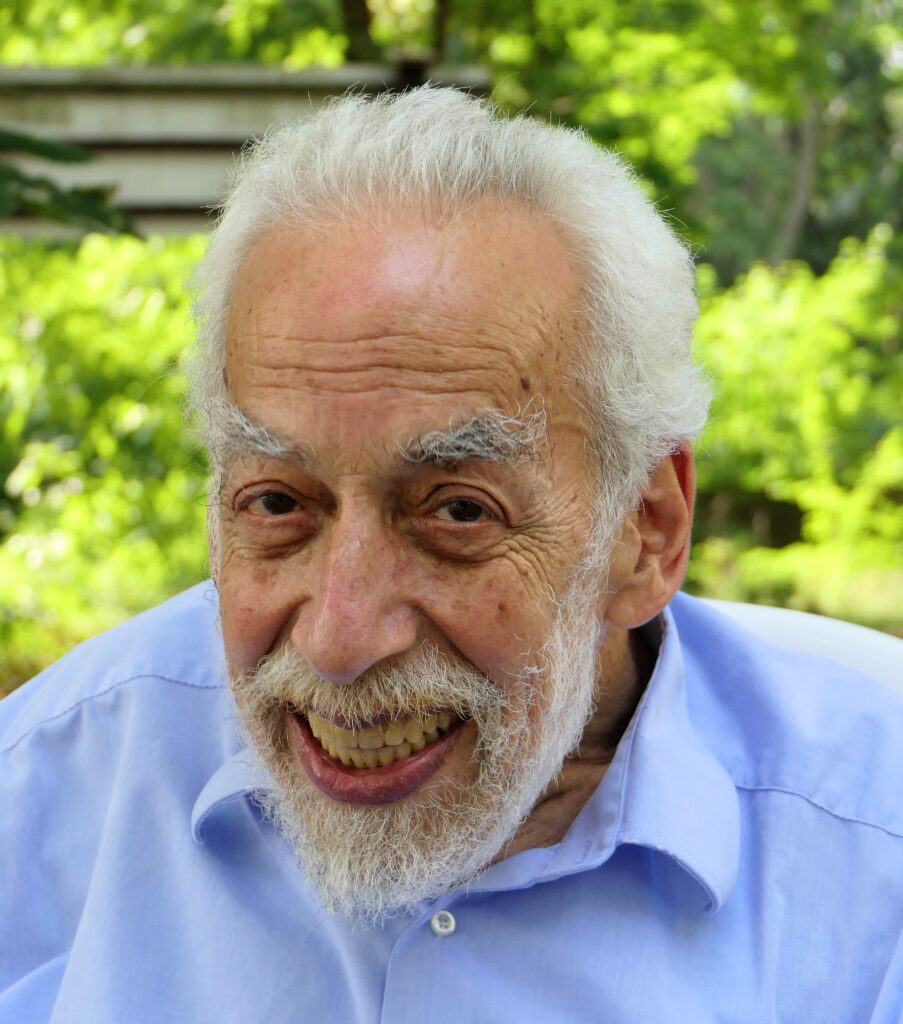

What character! What an impressive person. In his presence one felt lifted up.

To talk with him was always a pleasure, even if his characteristically mischievous smile was sometimes irritating. Had I expressed myself naively? What had amused the docile man? But no, Thomas Kuczynski took everyone and everything seriously. Even if he sometimes seemed to float above the clouds, to walk in far-off spiritual spheres, he was down-to-earth, completely of this world, open to earthly problems, worries, hardships, and even the supposedly most banal questions.

He never made a fuss about his grandiose family background. Sometimes one even had the impression that it was unpleasant for him to be asked about it. But he was proud, of course. Not only a great heritage, but one that entailed obligations. A baggage that he did not want to shake off, nor could he. But others were always curious to look into it and expected corresponding stories and explanations from him. That can be annoying. Especially if you want to live your own life, as Thomas Kuczynski said in an interview with this paper. Which he did.

He had his own academic merits, he was able to step out of the shadow of his father and grandfather, he did not remain “merely” the son or grandson of a celebrity – a fate to which no few offspring of important people, whether in politics, science or culture, are condemned throughout their lives. And yet, even here, one cannot avoid at least indicating briefly who and what shaped the life and academic career of Thomas Kuczynski. Born on 12cNovember 1944, in London, where his parents Jürgen and Marguerite Kuczynski, both economists, had sought refuge from Hitler, his anti-fascist convictions and attitudes were practically born with him in the cradle. His mother had founded, among other things, the library of the Free German Cultural League in Britain, his father – economics editor in the Weimar Republic of Rote Fahne (Red Flag), organ of the German Communist Party (KPD) – prepared analyses for the US Strategic Bombing Service (which led historical ignoramuses in West Germany to accuse him, decades later, of being responsible for the destruction of German cities by Anglo-American bombers in the last year of the war).

In the uniform of the US Army, Jürgen Kuczynski returned to Germany in 1945, helped to secure documents of German arms production, and personally arrested the head of I.G. Farben, a corporation headed by war criminals that had profited not only from forced labour but also from the gassing of more than one million men, women, and children at Auschwitz. Fewer than ten years later, Jürgen Kuczynski appeared as an expert witness for Friedrich Karl Kaul, the GDR joint plaintiff, in the first Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt am Main, initiated by Hesse’s admirably courageous Attorney General Fritz Bauer.

Thomas Kuczynski’s grandfather, Robert René Kuczynski, a highly respected statistician and pollster, who was never a member of the KPD but who voted for it and helped organise the popular demand for the expropriations of the Weimar period, had already fled to Britain to escape the German anti-Semites in 1933, three years before his son. His daughter, in turn, known as Ruth Werner (her later pseudonym as a writer), and younger sister of Jürgen Kuczynski, placed herself at the service of Soviet military reconnaissance during the Second World War. She worked as an employee of the top spy Richard Sorge.

Thomas Kuczynski would forgive my excursion into his family saga. It belongs to him like a second skin. And he has undeniably followed in the footsteps of his predecessors, continuing what seemed to him to be the right thing to do.

In the 1960s, Thomas Kuczynski studied statistics at the Economics High School in Berlin-Karlshorst and wrote his doctoral thesis on the end of the Great Depression, which had begun in 1929 with New York’s “Black Friday” and contributed to the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany. From 1972 he worked at the Institute for Economic History of the Academy of Sciences of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), whose last director he became in 1988.

The destruction after 1989 of the GDR’s academic elite also affected this clever, creative, and erudite man. The fact that he had to contend with the vanities and superficialities of the free market must have been an imposition and anathema for him. He bravely took up the challenge. Capitulation, especially in the face of capitalists and their apologists, was not his thing. True, no bestsellers ever flowed from his pen. However, his works will long remain important!

Thomas Kuczynski calculated the claims for compensation for forced labour in Hitler’s Third Reich on the basis of “the additional revenues and profits generated at that time” (the unwieldy but academically appropriate title of his study), owed by the Federal Republic of Germany, at 180.5 billion DM. Thomas Kuczynski never abandoned his academic projects, a rare characteristic – especially among today’s scientists, who switch quickly and unabashedly from one topic to the next, flippantly submitting to the spirit of the times and commerce. Not so Thomas Kuczynski, who followed up his study with a volume titled Crumbs from the Rich Men’s Table, in which he upped the sum to be paid by the legal successors of the Nazi state to 228 billion DM (116 billion euros).

Another massive project, which demanded not less but even more effort and time from him, held him “captive” him for more than two decades – a voluminous (new) edition of the first volume of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, in which he finally realised Marx’s wish – never fulfilled during his lifetime or thereafter – to compare the German first edition with its French counterpart.

Thirsty for knowledge and undaunted, Thomas Kuczynski also considered other translations of this classic of Marxist economics. Much of the edition is therefore taken up with footnotes. No wonder that his work did not make it onto the Spiegel’s bestseller list.

Kuczynski’s ambitious undertaking was a response not only to Marx’s own request but also to that of the director of the Moscow Marx Engels Institute and editor of the first, incomplete Marx-Engels Complete Edition (MEGA1) David Ryazanov, cancelled at Stalin’s behest. The Odessa-born scientist was arrested in 1931 during preparations for a show trial of members of an alleged “Menshevik Headquarters”, sent into exile, and shot in 1938 as a “Trotskyist” in Saratov.

It is interesting to note at this point, for it shows how strongly mothers shape their sons, that Marguerite Kuczynski, a staff member at the Marx-Engels-Institute in Berlin (IML), was responsible for bringing into being a new edition of Marx’s Poverty of Philosophy for the Marx Engels Works (MEW) published in the GDR, in which she included a French edition Marx had annotated extensively, a volume she had discovered while doing archival study in Japan. And the son, of course, also contributed to the flourishing of MEGA2.

The demise of “real socialism” – a formulation of Erich Honecker, as Thomas Kuczynski always emphasised; he himself preferred the term proposed by his friend Fritz Behrens, “nominal socialism” – disappointed him but did not shake his resolve. He recognised that the economic causes of the failure outweighed the subjective errors. And he was convinced that this socialism, even though it perished, has not simply disappeared but will be resurrected in the sense of the Hegelian dialectic.

This man has now taken his leave of us at the age of only 78. He died on 19 August. Not only his books remain. So too do the many memories of his lectures and conversations. And there remains the episode during which Kuczynki was invited by this newspaper to serve as its economics editor. The experience did not end well. A daily newspaper under the merciless pressures of editorial deadlines cannot afford to ponder over formulations.

Alas. Yes, it is true that the editorial encounters with Thomas Kuczynski remain unforgettable. It sometimes seemed like a meeting with his father, Jürgen Kuczynski, who had insisted to the end in taking his manuscripts, background articles, stock market reports and commentaries with him to the editorial office.

Annette Vogt was her husband’s first reader and editor of his writings, and is of the same friendly and open-minded disposition as he himself always was. We wish her strength and confidence. And patience to secure and safeguard the treasure that is his estate, just as Thomas Kuczynski himself did, with the estates of his grandfather and his father. Annette, you can be sure that Thomas will be missed by many.

[1] Published in Neues Deutschland, 23 August 2023