Figures

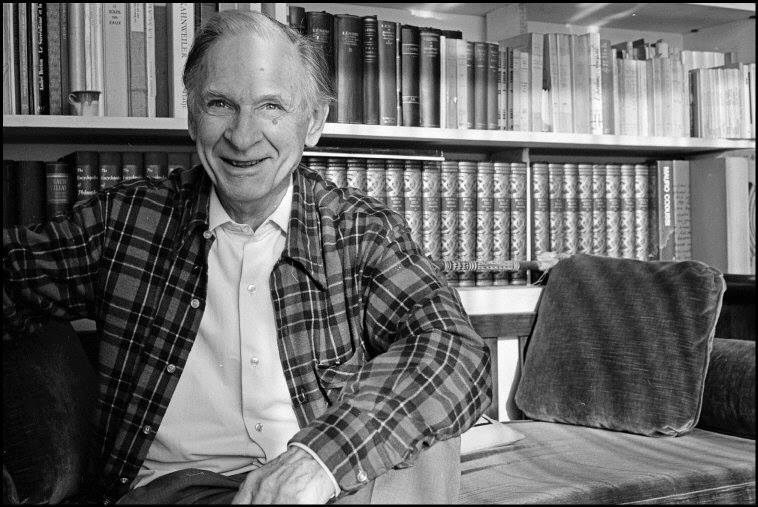

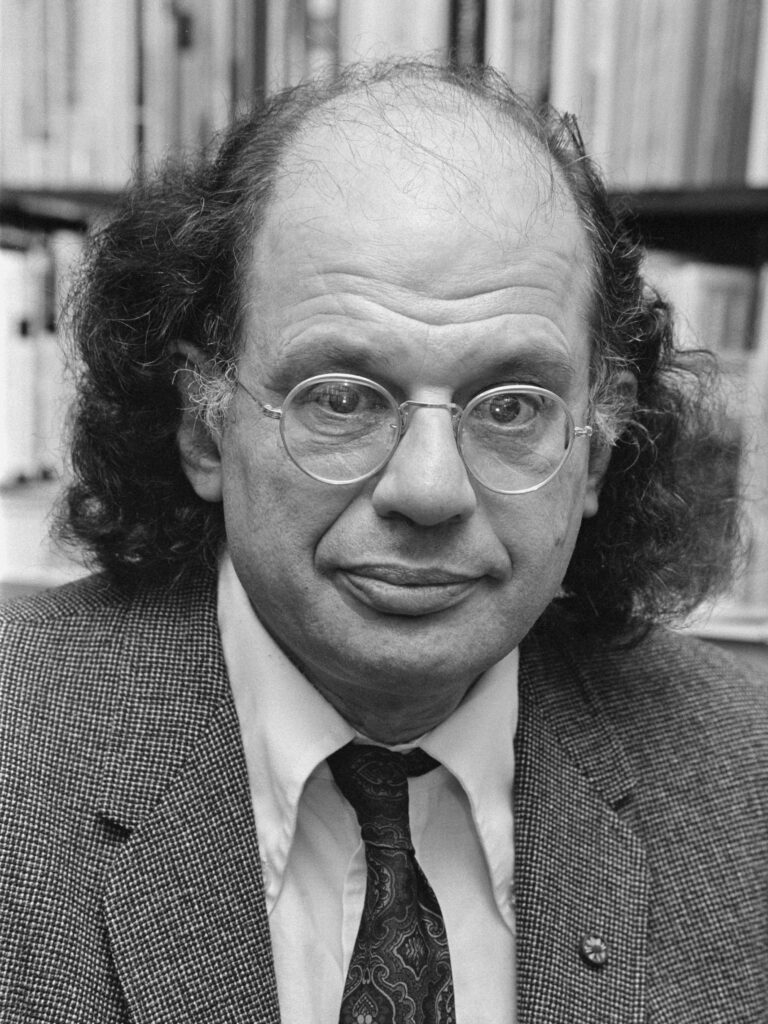

Paul Nizan

Paul Nizan (1905–1940), novelist and committed socialist, who left Europe for Aden in September 1926 when he was just 20, to spend six months there and write the philosophical memoir for which he is best known today. This brilliant piece of writing, called Aden, Arabie, published in 1931, was eventually reissued in 1960 with the proverbial Sartre preface. The book begins, famously, with the sentences “I was twenty. I will let no one say it is the best time of life”.

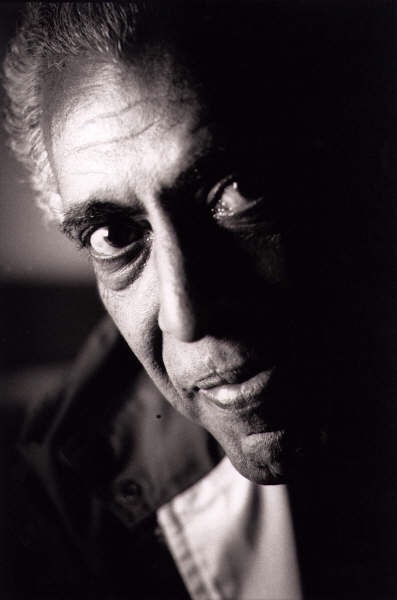

Pierre Naville

In 1926, Naville wrote a pamphlet seeking to steer the nascent movement of French Surrealists, with which he was associated as one of ‘19 founders’, beyond its spontaneous anarchism and hatred of bourgeois society towards what he saw as a more revolutionary politics grounded in historical materialism and in the “discipline” of working for a party committed, ostensibly (!), to a socialist revolution. Breton welcomed the pamphlet but replied, “All of us Surrealists want a social revolution… but at the same time we want to pursue our experiments in the life of the Mind without any external controls, including controls by Marxists”. The irony behind Naville trying to win the Surrealists to revolutionary politics (that is, to joining the Communist party in France) was, of course, that, just as Breton and Aragon did in fact join the Party, Naville himself was expelled from it for having sided with the Left (or Trotskyist) Opposition in Russia. He was expelled in 1928.

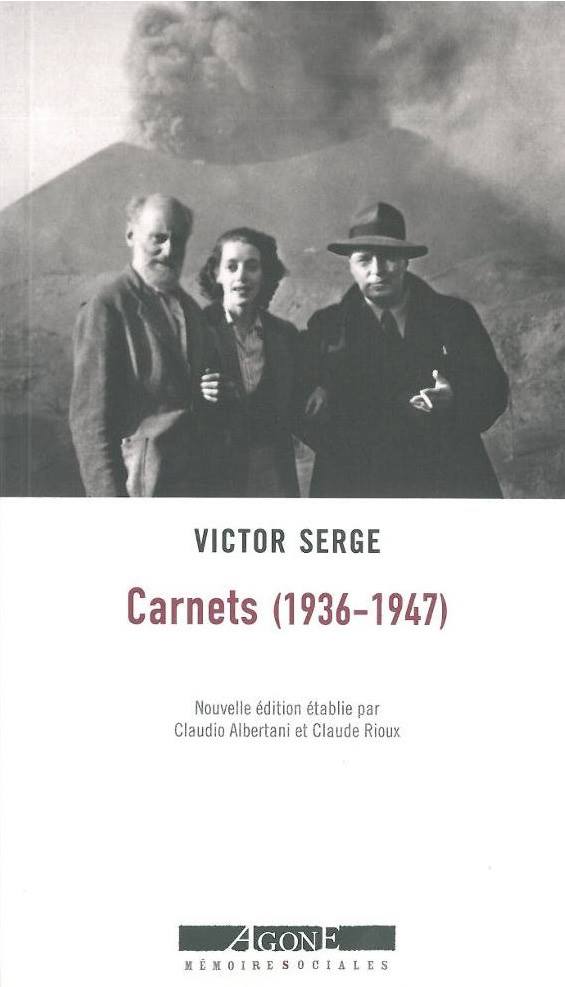

Victor Serge

Two excerpts from Victor Serge’s fascinating Notebooks (1936–1947), including a scathing but remarkably prescient forecast of the moribund future of the Fourth International. TheNotebooks are contained in a bundle of exercise books that were discovered in 2010, in a small town sixty kilometres south of Mexico City. They were published in full (836 pages) two years later by the Marseilles publisher Agone. Serge, who left Europe at the end of March 1941, in the same (last!) ship as luminaries like Lévi-Strauss and André Breton, arrived in Yucatán just over five months later, not long after Trotsky had been assassinated.

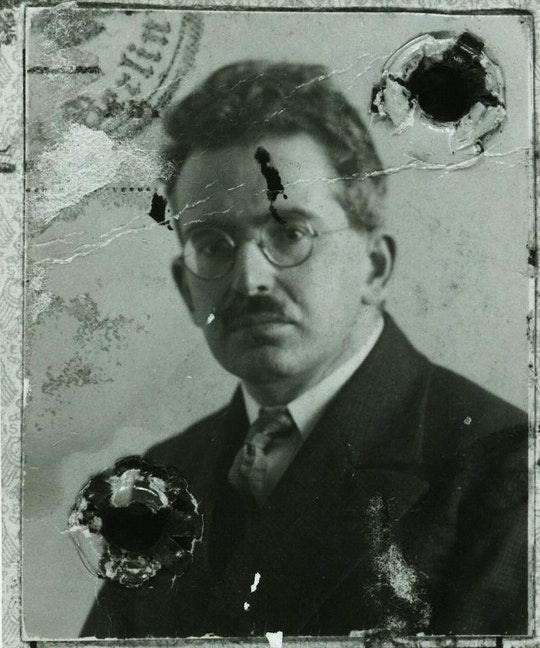

Civil-society-fascism & the death of Walter Benjamin

The cardinal fact to start from is that. if Walter Benjamin had committed suicide at Portbou, as we are told, how could he possibly have been buried in the local Catholic cemetery there? This, as a local resident pointed out to Mauas, the Argentinian photographer & filmmaker pictured here, was simply “unthinkable”, since suicides are never buried in Catholic cemeteries.

Abraham’s exile: the sad story of a young Marxist historian

Abraham’s exile: the sad story of a young Marxist historian

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pasolini’s horrific murder on an Ostia beach at the beginning of November 1975 was a political crime camouflaged (and widely accepted) as a homophobic hate crime. It was part of a chain of murders that stretched back to the assassination of Enrico Mattei, head of the Italian oil giant ENI, in October 1962 and to the subsequent kidnapping and killing of investigative reporter Mauro de Mauro, whom the Mafia killed in a Palermo suburb in September 1970. At the 2006 trial of the journalist’s murder, ex-Mafia witnesses (the type calledpentito) testified that De Mauro was killed because he was about to go public about Mattei’s 1962 murder as a result of research he had done for Francesco Rosi’s movieThe Mattei Affair. He told colleagues he had a scoop that was going to “shake the whole of Italy”. Of course, he never lived to publish that.

Allen Ginsberg

Marx drew the analogy between Moloch and capital at least once, in the economic manuscripts written between October and November 1862, which formed the last portions of Theories of Surplus Value. Here (in Notebook XV), he wrote, “The completeobjectification,inversion andderangement of capital as interest-bearing capital—in which, however, the inner nature of capitalist production, [its] derangement, merely appears in its most palpable form—is capital which yields ‘compound interest’. It appears as a Moloch demanding the whole world as a sacrifice belonging to it of right…”. Here it was finance capital that reminded Marx most immediately of the Canaanite god associated with child sacrifice.

Abdelrahman Munif

When Abdelrahman Munif wrote his great work of fiction in the eighties, his name for the five novels as a whole was Cities of Salt (Mudun al-milh). Today, this title is usually (and of course wrongly) used for the powerful first novel of the quintet, which deals with the ravages caused by petro-capitalism to the lives of Saudi Arabia’s indigenous Bedouin communities. What is interesting is that Munif’s own title for the first novel was al-Tih (التيه ). The routine translation of this as “wilderness” misses the true purport of the word in this context. Like Eliot’s Wasteland, what Munif was driving at is that in the Saudi kingdom, indeed in the whole of the Middle East, given the form it took, the alliances it struck and the devastation it caused, capitalism engendered a wasteland. The first of the five novels built a powerful image of the way the entry of American oilmen brought this about.

Chris Marker and Sans Soleil

“We do not remember. We rewrite memory much as history is rewritten. How can one remember thirst?” Chris Marker, Sans Soleil (1982).

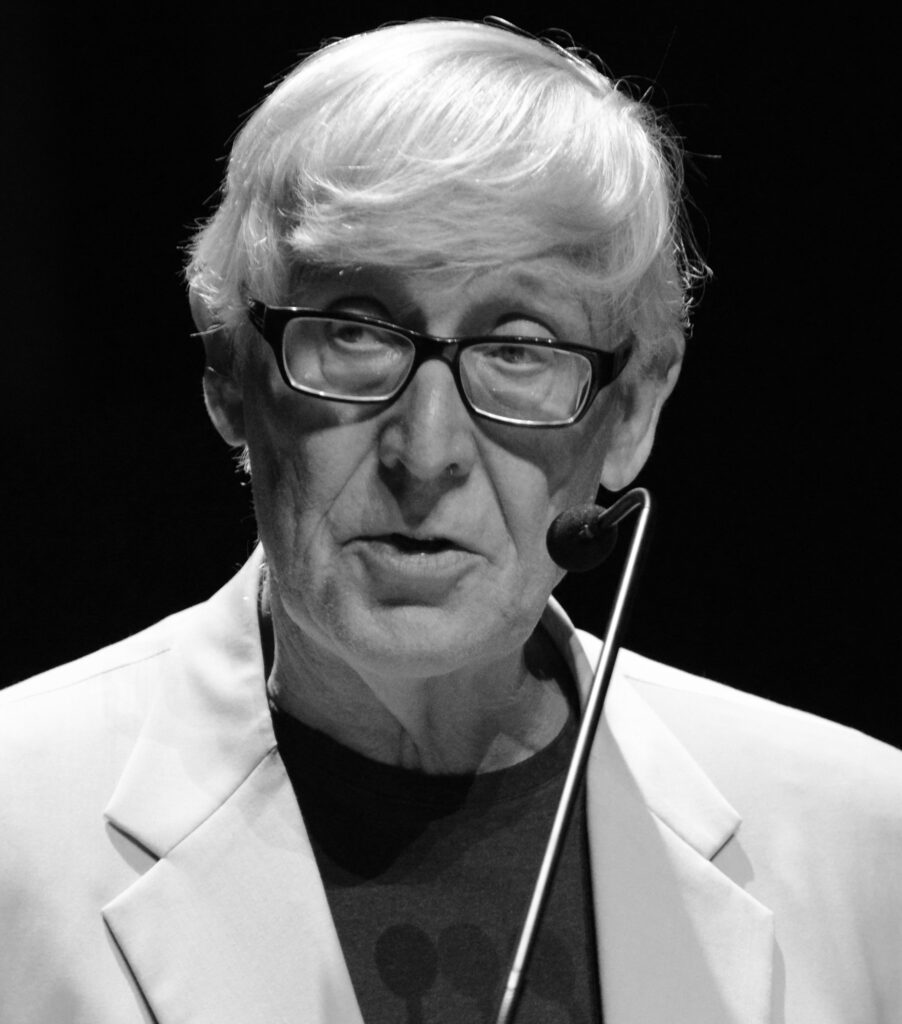

Perry Anderson

Arguably the most interesting essay to appear in Britain in 1968 was Perry Anderson’s “Components of the National Culture”, published in New Left Review in July/August of that year and later described by Ian Birchall as Anderson’s “ponderous tour through the sterility of British intellectual life”. Against the background of growing student unrest in many universities up and down the country, Anderson saw himself instigating “adirect attack on the reactionary and mystifying culture inculcated in universities and colleges … which it is one of the fundamental purposes of British higher education to instil in students” (p. 3). He argued that what set British students apart from their counterparts on the continent was an intellectual heritage marked by “the lack of any revolutionary tradition within English culture” (p.4). Marxist theory had never become naturalised in Britain, which remained the one European country “which—uniquely—never produced either a classical sociology or a national Marxism” (p. 11). The picture could not have been less flattering—a bourgeoisie quiescent in its seeming subordination to a governing aristocracy, a working-class party (Labour) “untouched by Marxism” (pp. 13-14), a society, England’s, defined by its “immutable character” (p. 17). To top it all, the backbone of British academic life (and this was the core thesis of the polemic) was formed by a “White”, counter-revolutionary emigration (p. 18), intellectuals who fled fascism to settle in Britain thanks to an elective affinity for its mediocre, conservative culture—Wittgenstein (philosophy), Malinowski (anthropology), Lewis Namier (history), Karl Popper (social theory), Isaiah Berlin (political theory), Gombrich (aesthetics), Eysenck (psychology), and Melanie Klein (psychoanalysis). These expats expunged any sense of historical time from their respective disciplines, relying on modes of explanation dominated by psychologism. They “codified the slovenly empiricism of (Britain’s) past” (p. 19). The one exception to the quiescent political tenor of this wave of intellectual refugees, viz. Isaac Deutscher, “was reviled and ignored by the academic world throughout his life” (p. 20). (Anderson might have added Arthur Rosenberg’s failure to find a place in British academia in the mid-thirties; but another historian who fled fascism and did land a job at a British university was of course Momigliano.) And, starting his critique with Wittgenstein, Anderson argued, the linguistic philosophy of the forties and fifties represented a deliberate renunciation of the traditional vocation of philosophy in the West (p. 22).

Tran Duc Thao

Tran Duc Thao (1917–1993) joined the École Normale Supérieure in 1939 and worked on Husserl under the supervision of Jean Cavaillès. Much later he would write,

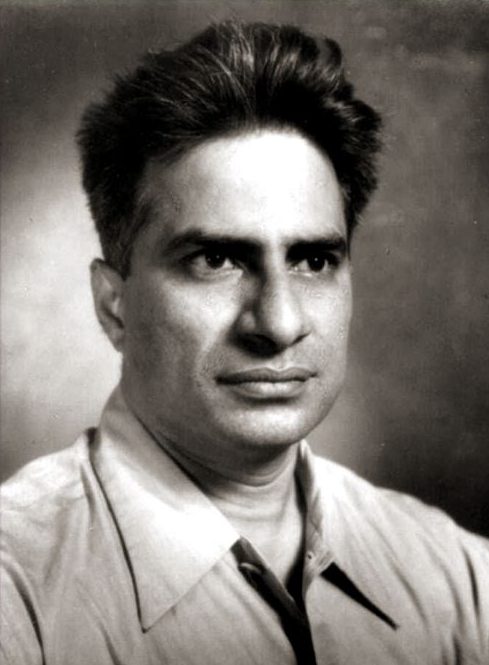

D.D. Kosambi

D.D. Kosambi (1907–1966), Indian mathematician, statistician, and Marxist historian, who was fluent in several European languages and active intellectually in a wide range of fields from genetics to Sanskrit philology. (His [Sanskrit!] dedication of a 1948 philological work, The Epigrams Attributed to Bhartrhari, significantly omits the name of Stalin from its list of dedicatees; “To the sacred memory of the great and glorious pioneers of today’s society, Marx, Engels, Lenin”.) Kosambi was also an early critic of “diamat” and the idea that all major societies passed through the same succession of modes of production, rejecting the notion that India ever knew slavery in the classical (Graeco-Roman) sense, and arguing thatcaste was India’s historically specific form of bondage so that India had a caste-based Asiatic mode for much of its history.