Figures

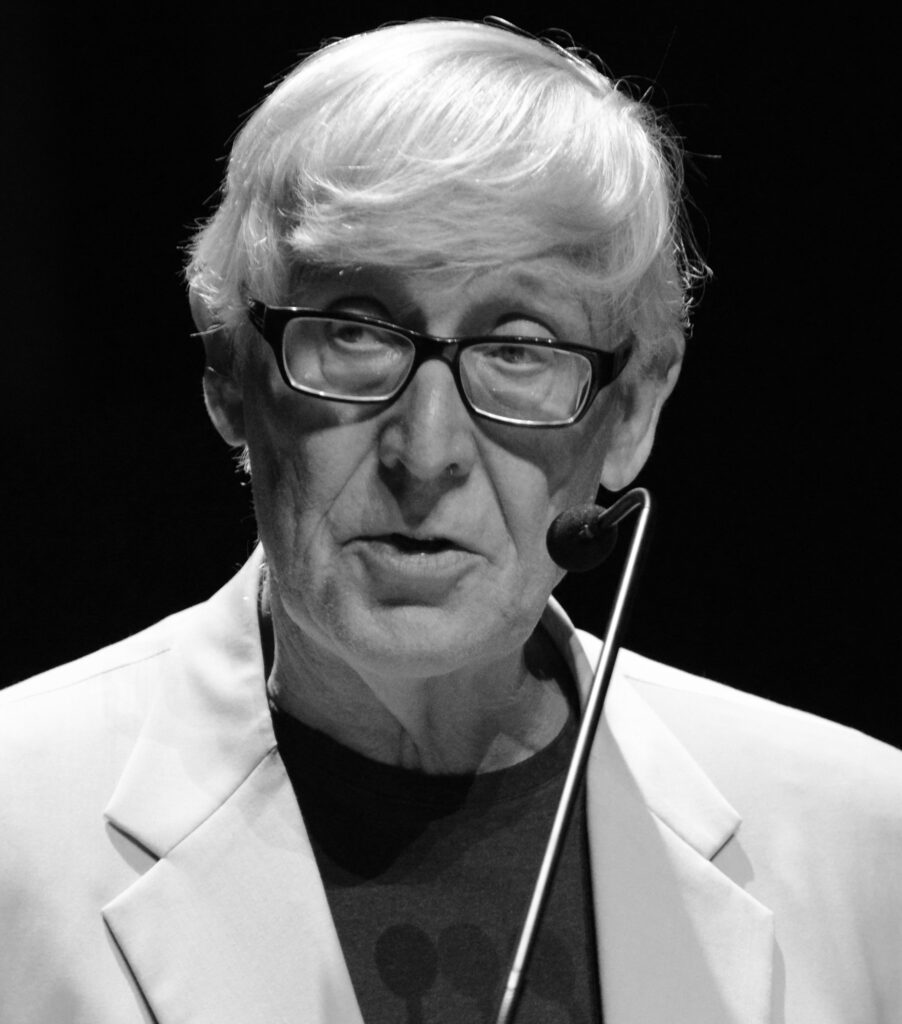

Chris Marker and Sans Soleil

“We do not remember. We rewrite memory much as history is rewritten. How can one remember thirst?” Chris Marker, Sans Soleil (1982).

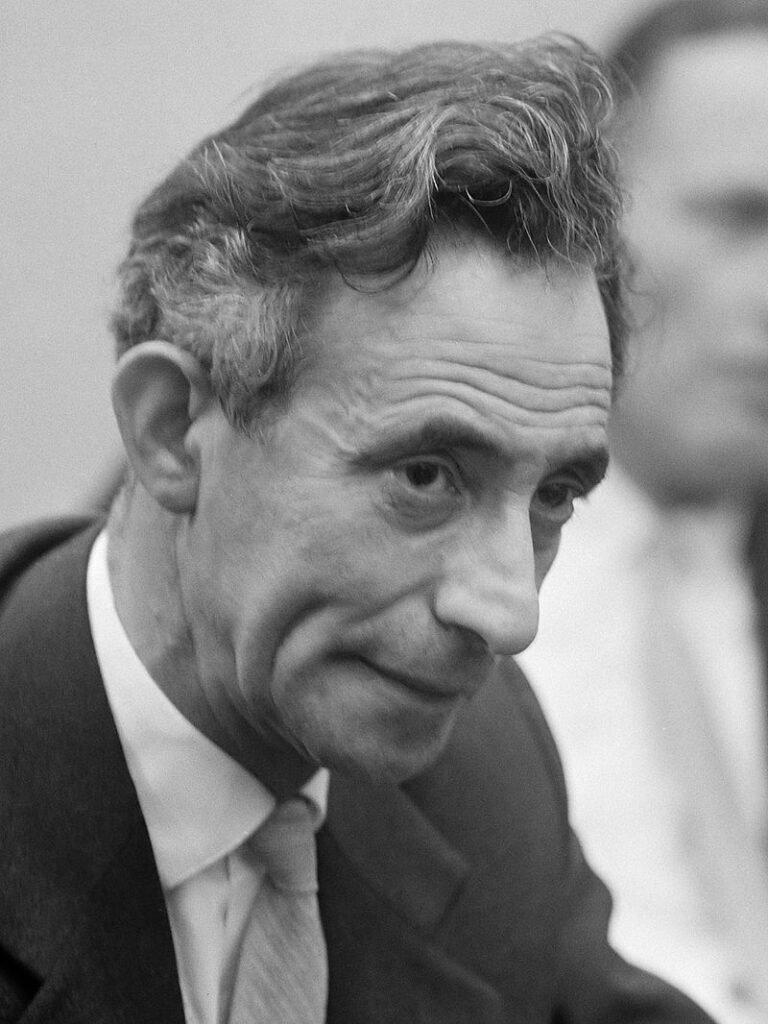

Perry Anderson

Arguably the most interesting essay to appear in Britain in 1968 was Perry Anderson’s “Components of the National Culture”, published in New Left Review in July/August of that year and later described by Ian Birchall as Anderson’s “ponderous tour through the sterility of British intellectual life”. Against the background of growing student unrest in many universities up and down the country, Anderson saw himself instigating “adirect attack on the reactionary and mystifying culture inculcated in universities and colleges … which it is one of the fundamental purposes of British higher education to instil in students” (p. 3). He argued that what set British students apart from their counterparts on the continent was an intellectual heritage marked by “the lack of any revolutionary tradition within English culture” (p.4). Marxist theory had never become naturalised in Britain, which remained the one European country “which—uniquely—never produced either a classical sociology or a national Marxism” (p. 11). The picture could not have been less flattering—a bourgeoisie quiescent in its seeming subordination to a governing aristocracy, a working-class party (Labour) “untouched by Marxism” (pp. 13-14), a society, England’s, defined by its “immutable character” (p. 17). To top it all, the backbone of British academic life (and this was the core thesis of the polemic) was formed by a “White”, counter-revolutionary emigration (p. 18), intellectuals who fled fascism to settle in Britain thanks to an elective affinity for its mediocre, conservative culture—Wittgenstein (philosophy), Malinowski (anthropology), Lewis Namier (history), Karl Popper (social theory), Isaiah Berlin (political theory), Gombrich (aesthetics), Eysenck (psychology), and Melanie Klein (psychoanalysis). These expats expunged any sense of historical time from their respective disciplines, relying on modes of explanation dominated by psychologism. They “codified the slovenly empiricism of (Britain’s) past” (p. 19). The one exception to the quiescent political tenor of this wave of intellectual refugees, viz. Isaac Deutscher, “was reviled and ignored by the academic world throughout his life” (p. 20). (Anderson might have added Arthur Rosenberg’s failure to find a place in British academia in the mid-thirties; but another historian who fled fascism and did land a job at a British university was of course Momigliano.) And, starting his critique with Wittgenstein, Anderson argued, the linguistic philosophy of the forties and fifties represented a deliberate renunciation of the traditional vocation of philosophy in the West (p. 22).

Tran Duc Thao

Tran Duc Thao (1917–1993) joined the École Normale Supérieure in 1939 and worked on Husserl under the supervision of Jean Cavaillès. Much later he would write,

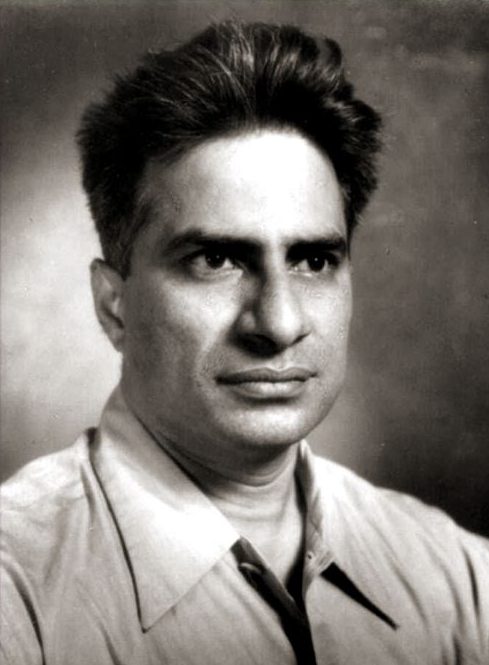

D.D. Kosambi

D.D. Kosambi (1907–1966), Indian mathematician, statistician, and Marxist historian, who was fluent in several European languages and active intellectually in a wide range of fields from genetics to Sanskrit philology. (His [Sanskrit!] dedication of a 1948 philological work, The Epigrams Attributed to Bhartrhari, significantly omits the name of Stalin from its list of dedicatees; “To the sacred memory of the great and glorious pioneers of today’s society, Marx, Engels, Lenin”.) Kosambi was also an early critic of “diamat” and the idea that all major societies passed through the same succession of modes of production, rejecting the notion that India ever knew slavery in the classical (Graeco-Roman) sense, and arguing thatcaste was India’s historically specific form of bondage so that India had a caste-based Asiatic mode for much of its history.

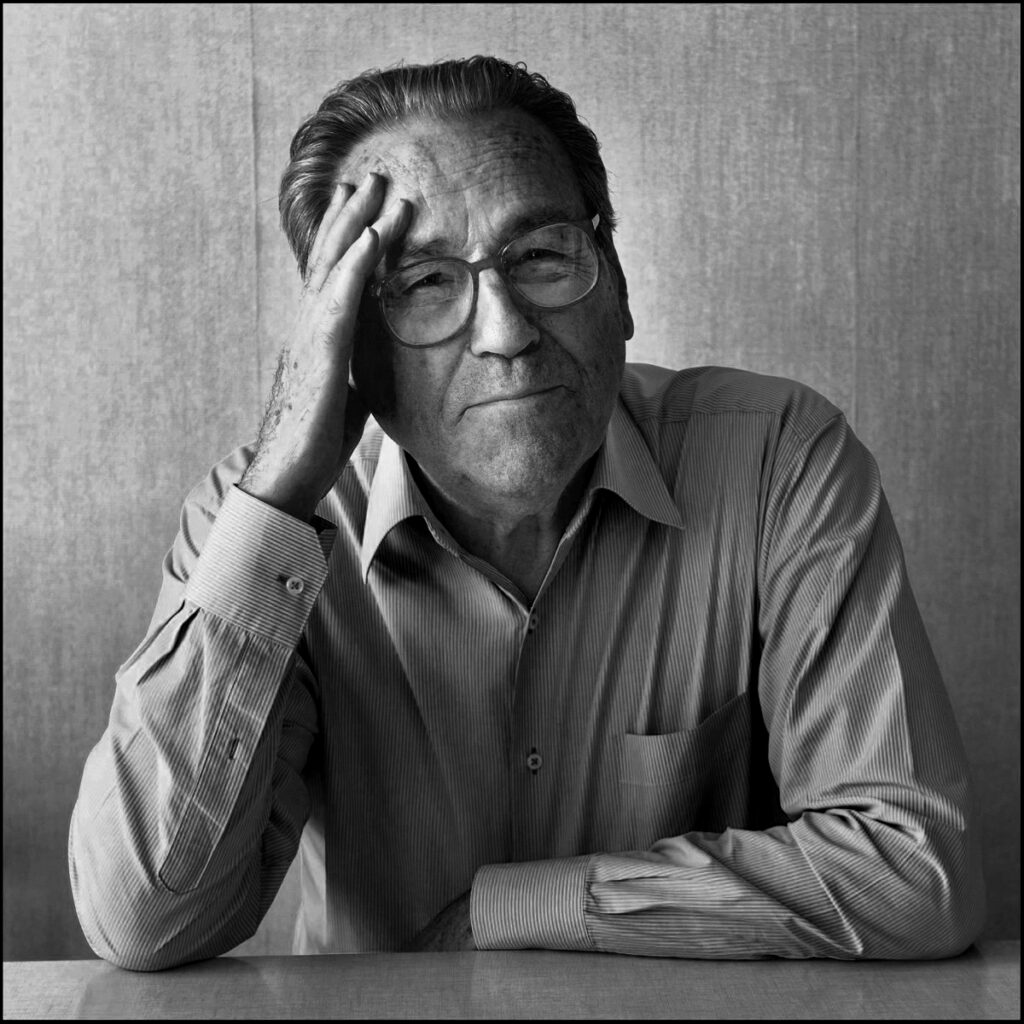

Lucien Seve

The philosopher and communist militant Lucien Sève died, aged 93, on the 23rd of March 2020. Lucien had been a close friend for over thirty years. The experience of reading his books, and then of our regular meetings, played a decisive role in my life. Regardless of whether we agreed or disagreed on a question, he was always a kindly and uncompromising interlocutor, unceasingly generous, brilliant and funny – a man of exceptional humanity. This text, written in sadness and anger, has no other ambition than to be a homage and an invitation to read or reread his – insufficiently known and discussed – work.

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Revolutionary Russia’s avant-garde with the Japanese writer Tamiji Naito, Moscow, May 1924 (photo by Anatoly Cemenka). From left to right: Pasternak, Mayakovsky, Naito, (diplomat) Arseny Voznesensky, Olga Tretyakova, Eisenstein, and Lilia (or Lili) Brik. Mayakovsky always seemed to tower over these gatherings, as he does in this photo with that ubiquitous fag.

Roman Rosdolsky (1898–1967)

In 1948 the Ukrainian Marxist Rosdolsky wrote a devastating critique of the “nationality politics” of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, the paper that Marx and Engels published and used as the platform for their interventions in the uprisings and struggles that surged around the “bourgeois” revolutions of 1848. Rarely has any Marxist exposed the limitations of any of the concrete political stances taken by Marx and/or Engels with more frankness (less restraint) or more theoretical lucidity. Rosdolsky’s critique focused on the way the paper viewed the aspirations of the Czechs, Croats, Ukrainians and other East European nationalities, starting with the unrestrained racism of (especially) its Vienna correspondent. To Rosdolsky the former (the views espoused by Marx and Engels) mattered more than the latter (the outrageous Slavophobia of this or that correspondent), since it affected the way revolutionary socialists would view struggles for national emancipation.

Sartre and his Critique of Dialectical Reason

In his Critique of Dialectical Reason, Sartre recasts Marx’s notion of alienation as our experience of the practico-inert. Alienation, Sartre suggests, is our ‘experience of the materialised result’. ‘It is no longer the positive moment in which onedoes, but the negative moment in which one is produced in passivity by what the practico-inert ensemble makes out of what one has just made’ (vol. 1, p. 337). If we say, the worker produces capital, then that is simply a shorthand way of saying what Sartre has just said. ‘What one has just made’, the product of one’s labour, becomes capital (a commodity that belongs to the capitalist) thanks to capital (thanks to a ‘practico-inert ensemble’ which is the accumulation of capital and the system bound up with it). As a wage labourer the worker is a ‘worked Thing’ (p.325), and as capital ‘worked matter’ is the ‘inert meaning of the worker’ (p. 328).

Benjamin Aäron Sijes

Much of the work of Dutch historian Benjamin Aäron Sijes (1908-1981) revolved around the Second World War. He wrote about the persecution of Roma and Jews by the Nazis, forced labour of Dutch workers during the occupation and the February strike of 1941 that broke out in protest against the anti-Semitic measures of the occupiers.

Nico (Niek) Engelschman

Nico (Niek) Engelschman (1913-1988) was a Dutch actor, resistance member, and pioneering gay-rights activist. During the Nazi-occupation, members of the socialist group around the journal De Vonk (The Spark) met at his house. Together with his brother, Engelschman helped several Jews escape deportation by finding hiding places for them. He would later play down his activities during the occupation.

Chris Pallis/Maurice Brinton

‘The concept that society must necessarily be divided into “leaders” and “led”, the notion that there are some born to rule while others cannot really develop beyond a certain stage have from time immemorial been the tacit assumptions of every ruling class in history. For even the Bolsheviks to accept them shows how correct Marx was when he proclaimed that “the ruling ideas of each epoch are the ideas of its ruling class”.’

Alfred Sohn-Rethel

Alfred Sohn-Rethel (1899–1990), who in his major work Intellectual and Manual Labour, completed in 1951 but published two decades later, argued that the ‘real abstraction’ of exchange is the true origin of abstract (mathematical) thinking and, through that, of scientific thought more generally. Thus, the evolution of money and that of science run parallel to each other, both beginning in archaic/classical Greece with the invention of coinage c.680. This thesis, of ‘the secret identity of commodity form and thought form’, remains unique in being the only major attempt to integrate epistemology into historical materialism via Kant, or the problem Kant poses in theCritique of Pure Reason, and Marx’s theory of value. (For later development on broadly similar lines see Richard Seaford,Money and the Greek Mind (2004) and R. W. Müller,Geld und Geist (1977))