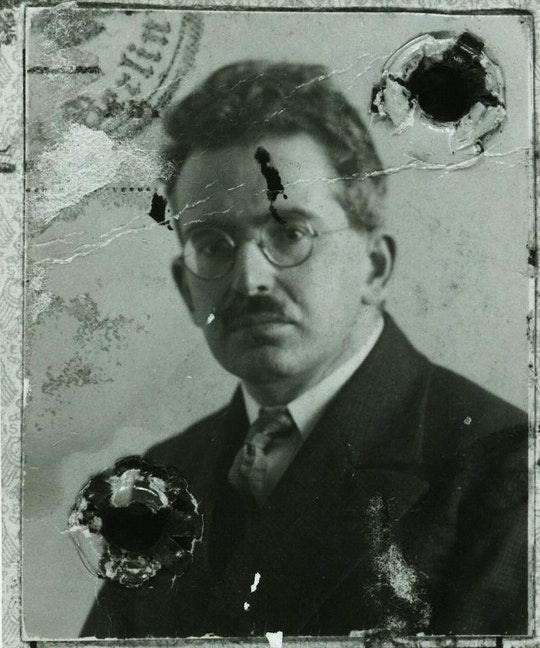

The cardinal fact to start from is that. if Walter Benjamin had committed suicide at Portbou, as we are told, how could he possibly have been buried in the local Catholic cemetery there? This, as a local resident pointed out to Mauas, the Argentinian photographer & filmmaker pictured here, was simply “unthinkable”, since suicides are never buried in Catholic cemeteries.

David Mauas’s brilliant documentary Quién mató a Walter Benjamin? (Who Killed Walter Benjamin?) (2005), which is a painstaking reconstruction of what is likely to have happened to Benjamin, even establishes the identity of his killer (though this man acted with the complicity of a whole coterie that included the police, the parish priest, the judge, and crucially the owner of the hotel at which Benjamin stayed the night). The man in question was a Portbou doctor and leader of the local Falange (the Spanish variant of fascism, established back in 1933). His name was Dr. Gorgot. Mauas’s basic reconstruction is wrapped up in fifty minutes.

First a quick background. Lisa Fittko who served as a guide for political refugees crossing the border into Spain says they set out for the border on 26th September. Since Benjamin is not known to have spent more than one night in the hotel at Portbou, this has to be the correct date. He died on 27th September. Eric Fromm’s future wife Henny Gurland who made the crossing along with Benjamin and her teenage son Joseph later recounted, in a letter she wrote in October that year, that they arrived in the evening and “went to the police station to request our entry stamps”. There they were told that stateless persons could no longer travel through Spain and would be taken back to the border in the morning. They were deeply distressed. They spent the night at one of two local hotels under guard. Then, “[a]t 7 in the morning [morning of the 27th!!] Frau Lippman called me down because Benjamin had asked for me. He told me that he had taken large quantities of morphine at 10 the preceding evening and that I should try to present the matter as illness; he gave me a letter addressed to me and Adorno TH. W….(sic!) Then he lost consciousness. I sent for a doctor, who diagnosed a cerebral apoplexy; when I urgently requested that Benjamin be taken to a hospital, i.e. to Figueras, he refused to take any responsibility”.

What is disconcerting in this account is the ostensible fact that Benjamin had consumed a vast amount of morphine at ten the previous night, yet was conscious enough to talk to Gurland at seven the next morning. Even Rolf Tiedemann told Mauas “I remember that I was also suspicious (when I read this). I asked a doctor whether it was possible”. Narcis Bardalet, a medical professional, emphatically ruled it out. “Someone who decides to commit suicide at night and takes 10, 15 or 20 morphine pills couldn’t possibly be lucid by seven the next morning … [or] by 9 in the morning”.

Here’s a condensed summary of those final fateful hours, as Mauas tells it in his documentary. Benjamin, Gurland and her son were clearly taken to the Hotel de Francia under guard. The owner of the hotel was one Juan Suñer Planas. According to Francesc Rosa, the oldest interviewee in Mauas’s film, “Suñer had joined the Fascists during the war and became Justice of Peace; his wife Eva Rafregau was French”. (Suñer and his wife would both flee to Venezuela after the war, to avoid arrest by the French.) One of the interviewees Juan Ramon Capella remembers asking Suñer whether Benjamin had killed himself. He was told that Benjamin had fallen ill and “was visited by a doctor several times”. (The doctor’s bill dated 28 September listed 75 pesetas “for 4 visits with injections, checking blood pressure and bleeding the traveller Mr. W.B.”) It was Suñer who went to fetch the doctor. Although it was the village doctor Ramon Vila Moreno who signed the death certificate on 27 September, Vila had been away from Portbou the whole of the previous day (Thursday), visiting his brother’s family at Figueres. It is unlikely that Vila was the doctor who visited Benjamin “several times”. In fact, he was quite upset when he heard that someone had actually died. Anna Caixas, a former employee of a nearby hotel who knew him, couldn’t explain why he was so upset. A plausible reason could well be that Vila had not been called to see Benjamin when he was actually available during the early hours of 27 September. Mauas probed the issue further and found that the doctor who actually visited Benjamin was one Dr. Gorgot, whom Vila disliked intensely and who hated Vila.

Pedro Gorgot, who had studied medicine in Barcelona and Paris joined the fascists during the war. In 1940, after Franco’s victory, he went back to Portbou, where he became one of the local leaders, together with the mayor and the priest. Doctor—mayor—priest. This was the inner core of Portbou’s fascist branch, the local Falange. Gorgot was the leader; the mayor’s house was where they used to meet; and the parish priest was an arch-reactionary called Father Andreu Freixa who had fled the Republicans to go into temporary exile in France.

Here’s a transcript of this part of the documentary:

The mayor Guixeres lived right across the street from the hotel; right in front of the hotel. Hotel Comercio was on the Rambla, at most 100 meters away from Hotel de Francia. “That’s where the mayor would meet the Falange members. They had their meetings here, in this room” (Simó Granollers, former hotel worker). So in this same room you heard a conversation saying they’d gotten rid of him. “That’s all.” Who was the Falange leader at the time? “At that time I think it was Dr. Gorgot. “ Mauas asks Antonio Lassiera, Can you remember which doctor visited Benjamin when he committed suicide? He replies, “I think it was Dr. Gorgot. Gorgot.”

Benjamin’s killers were in a hurry to complete the formalities of a burial. “This event [Benjamin’s burial] is full of incorrect procedures. If you look at the death register, you see that not all the information was entered at the same time. The Judge’s name was filled in afterwards, which doesn’t make much sense” (Francina Alsina). In fact, “The judge who drew up the certificate claimed he was under pressure. Pressure from above. In other words, he’d been told ‘Make it short and just write down this man’s basic information’” (Narciso Alba, lecturer at Perpiñán).

Finally, about the Hotel de Francia, “A lot of Germans ate there because the food was excellent” (Lassiera). To Novell Mauas says, Someone told me that during those years there was a rumour in the village that Mrs Suñer had contact with the Germans, giving information , to which he responds, “That’s what people said, that she could have been an informer, or a collaborator, so to speak. It could be, it could be, it could be.” Alba is asked, What happened to Suñer as the years went by? “Suñer went to Venezuela when the war was over, but he went to Venezuela for a reason, for the same reason that the Germans left when they were being tracked down to be tried in Nuremberg or somewhere else … their lives were in danger, because the French authorities were looking for him, looking for those people to send them to trial. That’s why he had to go into hiding for a while for being a collaborator” (Alba).

Benjamin’s fellow travellers all arrived safe and sound in Lisbon, on the afternoon of 30 September. Benjamin himself had an entry visa for the USA as well as transit visas to travel through Spain and Portugal. He had planned to sail to the US from Lisbon.

You can watch the documentary here.

Henny Gurland’s October letter can be found in Gershom Scholem, Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship.

By Jairus Banaji