Articles

Lenin’s Alternative: Dual Power and a Politics of Another Type

The following essay is a revised and expanded version of the author’s online intervention entitled “Lenin’s Alternative: A Politics of Another Type”, which took place on 25 May 2024, as the closing address of the international series of events Leninist Days/Jornadas leninistas (27 January to 25 to May 2024), organised in commemoration of the centenary of the death of Vladimir I. Lenin.

Dan La Botz: The Intellectual Autobiography of an American Leftist

I am almost eighty, an age when one begins to think about what one has done, what one has accomplished in life. So, I have been looking back on my forty-year career as a writer about labour and social movements. During this time, I have written principally about the importance of democracy in the labour movements, in society and in politics. I have written about ordinary working people’s attempts to take control over their workplaces, their labour unions, and of the political parties in which they became involved or created. I explore how ordinary people often ran into the power of the bureaucracies of unions, parties or the state, whether in the United States, Mexico, Nicaragua, or Indonesia, bureaucracies that frustrated their desire for control of their own lives.

On Jan Rehmann’s Deconstructing Postmodern Nietzscheanism: Foucault and Deleuze

Engels after Marx: a (critical) defence

Frederick Douglass and Karl Marx on the Paris Commune and the Labour Question in the United States

Critical Theory without political praxis? A discussion with the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung

Edited by Max Horkheimer for the Institute for Social Research, the journal Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung stands in admirable contrast to the usual grey publications from the emigration-circles. From Thomas and Heinrich Mann to Brecht and Feuchtwanger, from Georg Bernhard to Hart and Hiller, from Stampfer to Walcher, Münzenberg and Pieck, those only reflect the general intellectual stagnation and decay. Apart from a small number of exceptions that we will discuss later, the contributions to this journal are on the contrary characterised by a high scientific level and purity in thought and words. Most of all, the essays by Horkheimer himself attract our interest. Horkheimer attempts to address the contemporary philosophical reaction – irrationalism, neo-empiricism, ‘neo-humanism’- with the tools of dialectical materialism, which he also calls critical theory.

John Bellamy Foster Interviewed by Daniel Tutt on Georg Lukács and The Destruction of Reason

In this interview, conducted on 10 February 2023, John Bellamy Foster speaks with Daniel Tutt about the work of István Mészáros and Paul Baran, contemporary irrationalist tendencies in left ecological thought, intensifying global class struggles and the continued relevance of Georg Lukács’s The Destruction of Reason (1952), recently reissued with an introduction by Enzo Traverso by Verso in 2021. The interview is being made available in advance of a forthcoming special issue of Historical Materialism, for which Tutt is a co-editor, dedicated to Lukács’s The Destruction of Reason.

I Am Afraid of AI

A Few Levels of Commentary

It was always about Marx and Freud: yesterday’s form, no doubt, of the age-old philosophical antinomy: mind/body, idealism/realism, base/superstructure, in a situation in which the opposition, the gap or break, reappears again within each term. The base has its own base/superstructure problem within itself, as does the mind: there is an interminable scaling at work, a fission, whose unimaginable end-terms are nothingness and infinity. (Even in Freud there is an obvious base and superstructure in the form of the Unconscious and its consciousness, while the latter is equally divided between itself and its unconscious ‘base’ in the super-ego.)

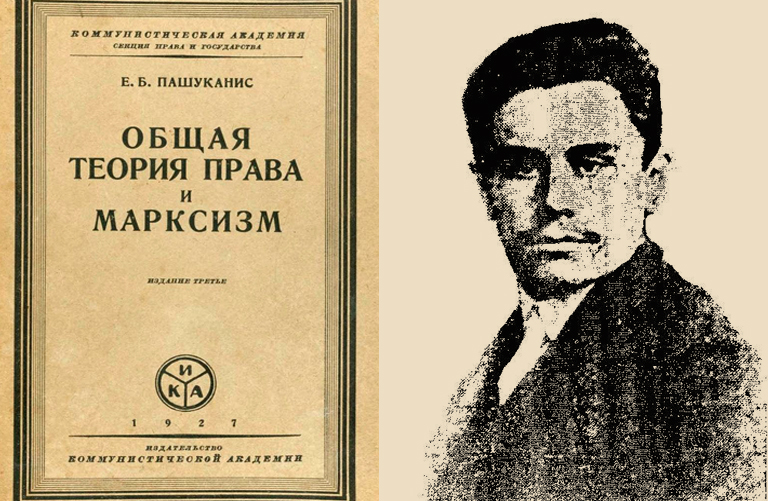

Three texts by Evgeny Pashukanis translated into English for the first time

‘Historical Materialism publishes three texts by Evgeny Pashukanis, translated into English for the first time.

“A Survey of the Literature on the General Theory of Law and State” (1923)

Jointly Edited and Translated by Rafael Khachaturian and Igor Shoikhedbrod.

“The Bourgeois State and the Problem of Sovereignty” (1925)

Jointly Edited and Translated by Rafael Khachaturian and Igor Shoikhedbrod.