‘Historical Materialism publishes three texts by Evgeny Pashukanis, translated into English for the first time.

They will soon appear in a forthcoming volume with Brill’s “Historical Materialism Book Series”, under the tentative title: The Revolution of Law: Developments in Soviet Legal Theory, 1917-1931, jointly edited and translated by Rafael Khachaturian and Igor Shoikhedbrod.

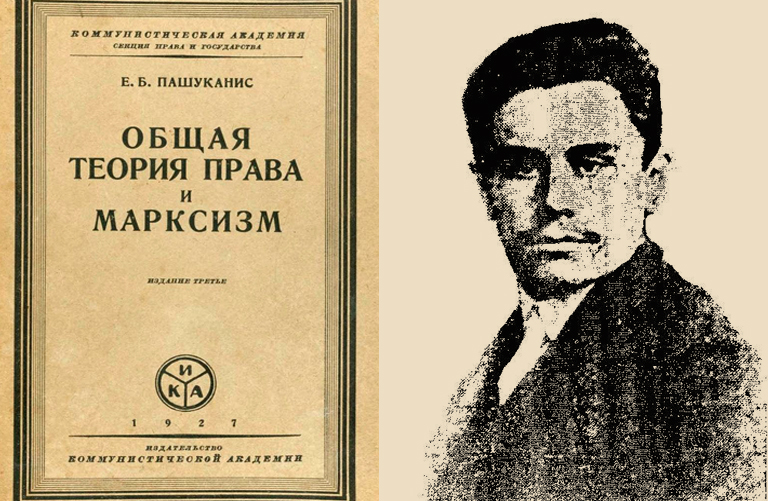

They are being made available as “pre-prints” for the centenary of Pashukanis’ General Theory of Law and Marxism.

In particular, these translations are being circulated because they provide a vivid sample of Pashukanis’ critical engagement with influential legal and political theorists both before and after the publication of The General Theory of Law and Marxism.

The texts are the following

Hegel. State and Law (On the Centenary of His Death)

This article was written by Evgeny Pashukanis in 1931, on the centenary of Hegel’s death. Several international congresses were held by Hegelian societies at the time to commemorate Hegel’s philosophical legacy, most of which are taken to task by Pashukanis in the article for their refusal to acknowledge Marxism-Leninism as natural heir and successor to Hegelian philosophy. Pashukanis uses the occasion to critically reflect on contemporary political appropriations of Hegel’s philosophy against the backdrop of fierce divisions between opposing camps—Marxist-Leninists (in which Pashukanis proudly situates himself), social democrats (or “social fascists” in Pashukanis’ terminology) such as Siegfried Marck, and full-blown fascists, such as Giovanni Gentile, whom Pashukanis calls “Mussolini’s faithful servant”. More substantively, Pashukanis displays an impressive command of Hegel’s representative works—The Science of Logic (with many references to Lenin’s Conspectus on that work), The Philosophy of History, The Philosophy of Right, and lesser-known works. He proceeds by underlining the critical-revolutionary and reactionary sides to which Hegel’s Philosophy of Right lends itself. Pashukanis ultimately sides with Hegel against his epigones, adversaries, and competitors, including Kant, celebrating Hegel as “the greatest representative of classical German philosophy” and reaffirming his bold view that Hegelian philosophy has been effectively “sublated” in revolutionary Marxism-Leninism

“A Survey of the Literature on the General Theory of Law and State” (1923)

This article offers what appears to be Pashukanis’ earliest and most sustained critical engagement with Hans Kelsen’s “pure” theory of law. There is good reason to believe that Pashukanis was reviewing Kelsen’s Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts (1920) and Der soziologische und der juristische Staatsbegriff (1922) as he was completing his General Theory of Law and Marxism (1924). In that famous work, Pashukanis dismisses Kelsen’s legal theory as a theory that “explains nothing, and turns its back from the outset on the facts of reality, that is of social life, busying itself with norms without being in the least interested in their origin (a meta-juridical question!)”.[2] Elsewhere in that work, Pashukanis contrasts Kelsen’s theory with his own theoretical attempt “to present a sociological interpretation of the legal form and of the specific categories that express it”.[3] In this article, Pashukanis spends more time unpacking Kelsen’s “meta-juridical” framework before pointing out its many shortcomings. Pashukanis also interrogates the extent to which Kelsen—a token neo-Kantian legal positivist—oscillates between a legal positivist and a legal naturalist framework when it comes to the broader arena of international law, a point that receives less attention in The General Theory of Law and Marxism. Kelsen responded with a polemic against Pashukanis and other early Soviet legal theorists in The Communist Theory of Law (1955). Pashukanis was shot in 1937 and was therefore deprived of his response to Kelsen.

“The Bourgeois State and the Problem of Sovereignty” (1925)

This article published nearly a decade before their in-person encounter, offers Pashukanis’ most sustained engagement with Harold Laski’s work.

And a note from the editors: there are instances where we couldn’t find English references to specific works by Siegfried Marck, for example, or passages from Hegel for which Pashukanis does not provide any references. If these are found along the way by readers, we would be happy to acknowledge the assistance of those individuals who bring this information to our attention.