Costas Lapavitsas: Money, money, money

Originally published in French in Periode: http://revueperiode.net/money-money-money-entretien-avec-costas-lapavitsas/.

BB: How would you describe your intellectual and political trajectory between Greece and England?

CL: I went to Britain when I was very young. I came out of the ferment in Greece after the fall of the Regime of the Colonels, so I participated in that period of very intense politicization. I also come form a left-wing family tradition. I was a Marxist and a socialist long before university, I didn't discover Marx at university. But I went to Britain very young- in the late 1970s – so my development has always been in the British and European left. I have been participating in the political and intellectual life in Britain and the rest of Europe for a long time now. In that sens, getting involved in Greek economic and political debates in the last 7 years was for me a return to Greece. But whatever I have done I tried to maintain distinctive aspects in my work that come from my Greek cultural origins. I firmly believe that we need to bring into social science something that we have from our selves and our own development. If we simply reproduce something we learned elsewhere we become hobbies.

BB: Profiting without Producing and also your brand newMarxist Monetary Theory draw on Hilferding'sFinancial Capital but also highlight its shortcomings. What are Hilferdings main theoretical insights for understanding contemporary capitalism?

CL: Let me first of all say that Hilferding, with whom I have profound political differences, is in terms of economics the only Marxist of the 20th century to have the claim to belong to the tradition of monetary theorists. Hilferding isn't just a Marxist political economist, he is also an important monetary theorist in his own right, and the only Marxist in that field in my judgment. Monetary in the broad sens, not so much because of what he has to say on money, but much more because of what he has to say on finance. The real contribution of Hilferding was on finance and without Hilferding it is very difficult to understand finance today. Hilferding is fundamental to any monetary theory of Marxist description for today. He offered two very important things. The first is an innovative way of analyzing the relationship between industrial capital and financial capital. He has understood financial capital for what it is: a separate type of capital and analyzed it separately. He explained the organic links with industrial capital. I would argue that the connection today isn't the same as then but the understanding and the way to analyze it comes from Hilferding. The second point is that Hilferding analyzed profit, financial profit. The return to financial capital, the connection between financial and industrial profit in innovative ways, is something which Marxist economics, at least in the anglosaxon tradition, has begun to understand only recently. 100 years after the publication of Hilferding's book. So in that regard too he is a very important Marxist theorist. Obviously, a last point, not so much about theory, Hilfdering was fundamental in understanding the change of periods in capitalism, which of course, Lenin took when he formulated his theory of imperialism. So that's a broader concern.

BB: Recently, empirical data at hand, Marxists such as Andrew Kliman and Michael Roberts repeatedly argued for the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall as the general cause of crisis. What role does this tendency play in your account of the 2007 crisis which is based on the pivotal role of finance?

CL: When i look on the development of the Marxist political economy, especially during the last 3-4 decades of the 20th century, to be honest I'm amazed. During that period a tendency has emerged explaining everything pretty much in terms of some putative tendency of the profit rate to fall. This kind of thinking has somehow mutated into the Marxist account of the macroeconomic performance of capitalism and the behavior of capitalism over time. I want to stress that this understanding, particularly the tendency of the rate of profit to fall because of the organic composition of capital, this understanding of explaining everything is a very new thing. Classical Marxists, Marx himself never did that. You won't find it in the great Marxists at the beginning of the 20th century, Rosa Luxemburg, Lenin, Hilferding, Kautsky , Otto Bauser, you won't find it in these people, and historically they were the best of the Marxists. You will not find it in Marx and Engels. This is a creation of the end of 20th century and it reflects in my judgment a decline of Marxism. It is Marxism becoming a narrow self-referential kind of intellectual endeavor, which has found some kind of principle and then keeps turning around it, irrespective of what the rest of the world says. So, in theoretical terms I find this kind of practice by Marxists terribly poor and saddening. It tells you very little in theoretical terms. Empirically it has no substance at all. I measured the rate of profit time and again. In fact, I'm publishing work now serious empirical work on the rate of profit in the USA and there is no evidence that it has been falling in any serious ways since the early 1980s. Of course it fluctuates but there has been no evidence that is has been falling in the long term. So neither theoretically nor empirically it makes sens. In terms of the theory of crisis finally, I want to stress something very important: crises are very complex events. A theory of crises is a very complex thing, by its own nature. To think that because presumably you have shown a decline in the rate of profit, let's say, because you have shown that there will be a crisis is to misunderstand what a crisis is. Often many of these so-called theories, basically demonstrate somehow a decline in the rate of profit, often to invent the decline and then on the basis of that add some kind of low level of sociology which presumably explains what the results are from the rate of profit. I don't like this kind of Marxism, I think it is confusing, misleading. The sooner Marxist theory gets out of this the better for all of us. Politically, as well it is appalling. The emphasis on the rate of profit to fall is a direct reflection of the political relevance of much Marxism. The less influential Marxism becomes among real people the more you stress the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. A lot of people think that if they demonstrated somehow that the rate of profit is falling, they are being revolutionary. Because they are showing that capitalism generates crisis and that capitalism will somehow create impossible situations for working people. They achieve nothing with that. It's pointless for political purpose. It's a reflection of political weakness. We need complex arguments that make sense. I've been involved in politics in Greece in the last years and i can tell you that if you start you analysis with the rate of profit to fall, most people don't know what you're talking about. And there are parties in Greece that reproduce that analysis, such as the Communist party, but they have been utterly irrelevant to political events in Greece in the last few years.

BB: Where does today's financialized accumulation come from? You mention 3 underlying tendencies which are monopolization, restructured banks and the consumption of workers.

CL: I think financialization is a very important dimension to contemporary capitalism and I understand it as a period in historic development. And as you indicated in your question, one must start with productive capital. Of course the rise of big business, monopoly capital, whatever you call it and its own behavior is very important. What we observe there, and it holds in France, it holds in Germany, it holds in England and the USA , is that that big business at the moment doesn't depend on banks as much as it used to. This is a fundamental point. For a long time big business has been in command over substantial money resources, capital which it doesn't it invest domestically. We have weak investment and huge availability of financial capital, and the use of this by big business to extract financial profit. Financialization starts with that. It is the result of underlying developments in the mode of production and the result of institutional changes in the state, the frame of the financial system and its own regulations. This remains the core reality, and the fastest financializing country is France. So that's were it starts. Then of course, there are changes in banks. Banking capital has its own logic. Banking capital is not some kind of capital that is dragged along by big business or alternatively commands big business, it has its own logic. It doesn't work towards big business in the way Hilfdering assumed it 100 years ago, or as Lenin assumed. And if the prospects of profitability from lending to big business are not very good, big banks will do other things. In that respect we have a change in banking. Banks are more geared in making profit out of transactions, out of dealing in big markets and out of lending to ordinary people and households. And as you know from my book, that's the 3rd thing that is very important: the penetration into households. That in some ways is the most evident aspect of financialization, the aspect that all of us see. Modern capitalism is very unusual in this respect. And that has economic and non-economic aspects. Of course households have economic behavior but there are also non-economic in what they do because people aren't businesses. You've got a family, to have to bring up children, you got to recreate labor power. This in not directly an economic process. So how finance connects to you is a very complex process that varies from country to country. But what we have is the extraction of profits directly form households, directly from workers. This is a new phenomenon. Value transfer from individuals and households directly to the financial institutions, this a very important development in the behavior of finance and households. A new form of exploitation.

BB: The Monthly Review current but also Giovanni Arrighi claim that there has been an epochal shift in the balance between the spheres of production and circulation, in favour of the latter. Similarly, there is the figure of banks as monied capitalists, often considered as rentier, distant from production, and predatory toward accumulation. Could you explain more broadly the relationship between finance and real accumulation?

CL: Finance is a very old thing. In fact we have evidence of financial transactions in classical Greece and ancient Rome. Very sophisticated transactions and clearly capitalistic, capitalistic in the sens of investing money to make money profit, which is the most basic dimension of capitalism. So financial capitalism is a very ancient thing. It existed long before the capitalist mode of production. These people knew how to make profits in a variety of ways, they don't needed a capitalist mode of production to make financial profits. This knowledge is there since, as it is inherent in being finance, working with money and money capital. That also contains a predatory element, because finance is a step removed from production and it makes profit out of real production, whether it is capitalistic or not. So ultimately finance doesn't care about production and if it makes profit by squeezing productive capital it will do so. So the predatory element is always there toward production and individuals. Finance will destroy individuals as we know from a long tradition. Industrial capitalism in the way Karl Marx and the great political economists discussed it in some ways was an unusual period. What happened in the years of intensified industrial capitalism is that for the first time in the history of humanity a system of finance emerged, not just financial activity. So a structured system of finance emerged. And this system was mobilized to serve the interest of industrial capital. As Karl Marx said financial capital is subordinated to industrial capital and serves it. And indeed that's how it worked in the 19th century in England and elsewhere. This is the classical model that Marx had in mind, where banking, stock markets and financial institutions served the accumulation of productive industrial capital. The 20th is very different, and 21th is again different. What we observed with the maturing capitalism is of course a break in this simple way of formulating and an increasing autonomy of financial capital. Financial capital has always had some potential for autonomy but in the 19th century it was kept under control by industrial capital. In the 20th century autonomy increased and even more with financialisaiton. With Hilferding we can think the autonomy of financial capital reestablishing itself and dominating industrial capital. It's a reversal of what Marx had argued, and this is Lenin's classical imperialism. During the 20th century industrialists came back and pushed financial capital back down during the period o f Keynesianism. Now finacializaiton can be considered as a second period of renewed ascendency of finance. This time, not by controlling industrial capital but by making profits in a variety of ways, by dealing with individuals and giving to the financial system a profound degree of independence, where it can expand in a variety of ways. This has happened while the industrial capital in the west hasn't been growing very much and where profits, although not falling, have not been rising significantly. So we have a re-balancing of the capitalist economy in the last 40 years in a way that is historically unprecedented. Finance expanded, production is more stagnant. This is financialization and it means some ancient tendencies reasserting themselves and Marxism needs to take that into account and needs to think innovatively and creatively.

BB: You consider that the crisis that has been triggered in 2007 is a peculiar one because of the distinctive significance of finance, which has its own internal logic. In this context, you hold that money is the basis from which credit and finance derive. What are the foundations of a Marxist monetary theory today?

CL: You've asked me 2 things. The crisis 2007-2009 isn't due to a falling rate of profit. Let's begin with that. Those who think that and that they are defending Marxism because they link it to some reality of capitalist economy are misguided. It's irrelevant. The crisis emanated from the heart of capitalism, but the heart of capitalism contains finance. The crisis emanated from very peculiar events. Just think about it: it is the fact that the poorest section of the US working class had borrowed very heavily, couldn't repay it, and these housing debts triggered a gigantic global crisis. In the context of Karl Marx this would have been unthinkable. And that tells you the transformations of capitalism and how we should integrate finance. Money is of course at the foundations of finance for a Marxist approach. And its importance has been demonstrated very vividly since the crisis. Marxist theory of money has also been a very problematic field for many reasons. In the Anglo-saxon world Marxist theory of money has historically been very week. In the German tradition and even more in the Japanese tradition it has always been much stronger. Only gradually its getting better in the Anglo-saxon world. My approach to it is this: logically, we must understand money as a commodity, as Marx said. But this is only the beginning. Once we understood it as a commodity then the next thing is to understand the evolution of money and the particular way in which credit money and fiat money work. These are the two most important forms of money for modern capitalism. Contemporary money from this perspective very important for 2 reasons. First of all, the great bulk of it is created by private banks through the credit mechanism. Second, and even more important, the foundation of this system, the ultimate means of payment, the legal tender is state fiat, convertible into nothing. It 's a promise to pay itself, nothing else, produced by the state through the banking system. That's what makes it different: it is fiat but produced through the banking system. This gives to the modern state enormous power: it allows him to drive interest rates down to 0 – which is unprecedented in the history of capitalism – essentially by producing huge amounts of this fiat money, which is possessed by banks. So what we witness today is a incredible explosion of the hoarding tendency. In gigantic dimensions this money produced by the state is hoarded by banks. So it is the ability of the state to create money and to put it in the hands of the banks that has allowed the modern state to deal with the crisis. Without that it would have been impossible. It is also this ability of the state to create money in this way, that has allowed the state to support financialization. This power of the state is placed at the service of the financial system. It allows the financial system to obtain liquidity, it drives interest rates down, it subsidizes the financial system by creating gaps between interest paid and interest received. It is a very powerful lever of managing the capitalist economy and supporting finance. That's for the domestic system. Internationally, the role of money is more complex and there it's the opposite of the domestic system. In the domestic use of money we have a degree of knowledge and management, according to specific purposes. Internationally, it's the opposite, anarchy. There is no money that can operate like that, there is no structure serving these purposes in the world markets. We have competition between states, contest between big businesses for payment, for transaction, for shifting wealth. These contests are mediated by forms of money created by powerful states, mainly the USA but also the EU to a certain extent, which compete with each other, but which are unstable. This is a source of the global uncertainty and instability which we are witnessing at the moment. We have been on the brink of a currency of a currency war for 2 years now. Whether it will break out we don't know but it shows the instability of the system globally. The international dimension of money, i can see no prospect of stabilizing it. Therefore, all the vast contradictions of the global capitalist system are manifested there.

BB: The concept of fictitious capital is relatively widespread in current debates. Could you explain the difference between financial profit from holding equity and financial profit from trading financial assets? And linked to that question, why is the figure of the speculator inadequate for the analysis of financial profit resulting from trading financial assets?

CL: I'm very skeptical of the use of the concept of fictitious capital and much of the debate around the figure of the speculator. Fictitious capital and speculation exist but I'm skeptical of stressing these things because it's the other side of the coin of the tendency of the profit rate to fall. Usually, that kind of Marxist analysis starts with the tendency of the rate of profit to fall and thinks it explains the world, and once it has done that it adds fictitious capital and speculators and thinks it has explained finance. So it is an incredibly jumbo. Now, fictitious capital is an idea that Karl Marx used, the simplest way to understand it is as net present value. Those who do finance will know that. To impute a monetary value to some fictitious capital that corresponds to the regular payment that one receives. You can do that, finance does it all the time. Marx was aware of this and said it is fictitious, and he was right. But there is no capital of this type. When you receive money regularly it doesn’t mean that there is some capital behind. If trade it however, if you trade the right to receive those payments you create a price for it, which is how finance works. You create a piece of paper that corresponds to this capital and gives you a right on payment, then someone has to pay money for it. That money isn't fictitious, it's real. When we talk about fictitious capital that's one thing, but it doesn't mean that the capital we observe in the financial markets is fictitious, far from it. This capital should be understood as loanable money capital. That's the real concept we need for finance. What Marxist theory should be spending its time discussing is loanable money capital, because fictitious capital is basically a widows cruse. It's a pot out of anything can come. It gives you very little intellectual leverage. The real issue is loanable money capital. Which allows to understand the real capital that is available in the money form and is transacted among participants in financial markets, through borrowing and lending usually, creating often buying and selling transactions. This takes the form of fictitious capital, it creates fictitious capital but underneath there is a reality of it which corresponds to loanable money capital. In my work, I've been concerned to point precisely this out. To find the bridge, because the profits out of finance are not fictitious, they are very real and made out of loanable money capital. So what happens there? Two things which are analytically and politically important. First, real profits emerge because some agents obtain rights to future flows of value. That can be future profits, wages, future anything. You obtain rights of that and accumulate them. That's a real source of return. The second thing that happens is the difference in monetary value between what you paid for a financial asset and what you receive for it. Capital gains, if you wanna call it like that, or capital losses. These are one-off differences in absolute terms of value, these are value transfers, they aren't flows and that's another mechanism of profit making in the financial markets. Financial profits then should be analyzed through a combination of these 2 things: change in the rights of future flows of value and change in differences in money paid and money received to obtain assets, capital gains. Here a key analytical instrument comes from Hilferding. Much of those capital gains, or the access to profits will depend on the rate of return, and on the rate of interest on the market. Hilferding was the first Marxist to analyze that, to analyze the systematic difference between the rate of profit and the rate of interest. He proposed the concept of „profit of enterprise“. Marxists should spend their time analyzing this instead of trying to show that the rate of profit is falling.

BB: To what extent has financialisation transformed the social relations in developed capitalist countries?

CL: Tremendously, that the simple answer because the change is enormous. One thing we need to stress is that we don't really have the return of the financial rentier. People extract rent, they extract financial profit but they don't seem to extract it by lending money or making money available. The rentier here, in the traditional political economy is the person that lends loanable money capital and makes it available. Such a thing is not immediately happening, this is not the age of the rentier. This is the age of the financial institution related to industrial business in an unusually way. It's the age of institutional finance in a very complex fashion, that mobilized funding from across society. From the perspective of workers the transformation brought by financialisation is very important. Finance has penetrated individual life. On the side of debt but also on the side of asset. Typically people in the Marxist tradition or on the left look at the side of debt only. And they think that this is how financialisaiton works, because of course indebtedness has increased. And often there is an analysis that says that debt has increased because income isn't high enough. People borrow to maintain their standard of living. This is fallacious thinking. It's just not possible to increase private debt systematically for 30 years because income isn't enough. Financial institutions that would have done that would have gone bankrupt a long time ago. So there are different processes. It isn't simply that wages are not high enough, of course real wages in many countries like the US have been stagnant for a long time, but the reason why people increased their personal debt is far more complex. The biggest element of debt is for mortgages, for housing, only a smaller part is insecure borrowing for consumption and even there we don't know exactly what is going on. Now, I suggest, the reason why this has increased in many countries is related to the development of real income, but more heavily, more closely it is related to the provision for basic goods, that households need: housing, eduction, health and so on, that make the consumption basket of the working class. Most provisions there moved away from social provision towards private provision. Private provision has been mediated increasingly by the financial system. Fiancliasation works in that way. So people became more heavily indebted because of commercialization of these activities, mediated by the financial system. Without negating the role of wage, the problem is much more complicated for the individual worker and household. And it affects the behavior of the worker. The workers feels the pressure of debt, he or she has a different behavior on the workplace, the worker feels that he or she can obtain goods from a variety of private providers, the mentality of the worker changes as a result because it's a constant process of keeping pennies and pounds in order and in place. A muzzle pressure comes from housing, which brings me to the assets. The left only looks at the liabilities of the workers but working people also have assets, and also financial assets. They have financial assets for pensions, a lot of workers put money aside for pensions and this is a big deal for them, and housing can be thought as an asset. You have your mortgage but you also have your house. So on the asset side finacialisation is also very prominent. People learn how to play with their house, expecting to make profits and that’s a very important mental process. People also come to rely heavily on private providers of pensions on the asset side and there again they might lose money or acquire rights in complex ways. So fnancialisation also works on the asset side, making profits for financial institutions. The combination of these two sides makes powerful results, which we see in everyday life. This doesn't only affect the middle class, but the working class also knows it very well. That creates new political pressures on the left. We must be able to offer concrete proposals to working people in this situation and know how to deal with the pressures they're facing.

BB: Regarding the countries in the periphery you claim that there has been no return to formal imperialism, but financialization in developing countries takes a subordinated character which is linked to the hierarchical nature of the world market. What are the features of subordinate financialization?

CL: That in some ways is the most interesting developments of the last 15 years in terms of the global system. We don't have a return to imperialism in the classical way. Those who consider that we have a return to imperialism in the way Lenin meant it have not studied Lenin carefully. Because Lenin talks about monopolization and unity of finance, banks and big business, which imposes trade controls, dominates the globe and redivides it. None of that is observable. And yet, we do have aggressive finance dominating the globe and penetrating everywhere, together with business, which is financialising itself. We do have forms of imperial imposition but not in the way Lenin meant it, which is why we don't have similar phenomena. There is no empire in the formal sens. On the contrary, what we see is that when these aggressive states intervene, they create chaos. Instead of creating empire and dominating and integrating it in their own system of control. The US, in particular since the 1990s, has created chaos when it intervened: in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and the Balkans. So imperial presence is there, it's aggressive, it's destabilizing and it's driven by the expansion of finance and the expansion of big business, establishing outposts everywhere but not in Lenin's way. For a long time, the imperialists wished to maintain open borders, free trade and free movement of finance. How that will end up we will see. In the same context, for the last 40 years we have had financialization, also in the emerging world, in the middle income countries, but not in the poorest. There foreign banks have penetrated and transformed the domestic system along the lines discussed previously (especially regarding households in countries like Turkey, India, Mexico, South Africa...). This has had implications for a variety of developing countries. What is interesting is that that financialization is clearly derivative of the financialization of the main countries. There financialization has occurred and expanded while these countries were growing and therefore it shows that financialisation doesn't necessarily mean stagnant production. The big unknown here is China, which might change everything. China is the last front in this regard because its economy is enormous, the financial system too, but China isn't yet financialized in the way that the mature or several developing countries are. In China we still have a broad outline of a financial system that serves the purposes of capitalist accumulation. We have the outlines of a system that is there to promote investment in big business, the extraction of profit from industry. That can still create financial bubbles or over-extension of credit, but in key ways it still serves the interests of productive accumulation. The are two reasons for that. First, the continuing role of the state. Much of the Chinese financial system is state operated. Second, the Chinese financial system is still not fully internationalized, there are still controls over the flows of capital. If China financializes, like Britain or the US or another core country, then we will have gigantic phenomena in the world economy. We need to think carefully about that if and when it happens.

Nick Dyer-Witheford: Cyber-Marx

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/cyber-marx-entretien-avec-nick-dyer-witheford/

We often say with some emphasis that information and communication technologies will soon bring the end of work, and therefore the disappearance of proletariat. Nick Dyer-Witheford adresses that new illusion, intrinsic to actual capitalism, by accounting for the generation of “surplus population” on a scale unseen before. There is no substitution of immaterial labour (or cognitive capitalism) to its traditional, material form, but polarisation : technology doesn’t lead to the aboliton of class composition but to its reconfiguration. The goal becomes then to determine how the different forms of exploitation are interacting, and how that will shape the future of cyber-proletarian struggles. (Période magazine)

- Every two months now, a new bestseller announces another disruption or even revolution of work and production elicited by technological progress: Richard Florida’s rise of the « creative class », Jeremy Rifkin’s « end of work » and « eclipse of capitalism », Martin Ford’s « jobless future », the « fourth industrial revolution » promoted by Klaus Schwab and the German government, etc... And yet, following authors like Ursula Huws1, you chose to name your last bookCyber-proletariat2, claiming that there still is a working class. Why would it still be relevant?

Jairus Banaji: Towards a New Marxist Historiography

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/pour-une-nouvelle-historiographie-marxiste-entretien-avec-jairus-banaji/

- When one takes a look at your published works, one notices a great variety of interests, from Value-Form Theory (“From the commodity to Capital: Hegel's dialectic in Marx'sCapital”), to Critical Theories of Fascism (Fascism: Essays on Europe and India) and to Marxist historiography and historical theory(Theory as History). Should one consider this various interests as different interventions within heterogeneous fields of research or is there a continuity and systematicity to be found in your work ?

Nathaniel Mills: Ragged Revolutionaries

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/revolutionnaires-en-haillons-entretien-avec-nathaniel-mills/

- In your book – Ragged Revolutionaries (University of Massachusetts Press, 2017) – you look at how African American authors (and especially members of the Communist Party of the USA, or close to it) have rethought the concept of theLumpenproletariat in “order to better explicate the socioeconomic and cultural structures of the modern United States” (p. 3). The fact that the concept ofLumpenproletariat is rather negatively-worded in “classical” Marxism and that African American leftists have reconceptualise it is a very interesting point, but why did you focus on authors and on literature? And why especially during the Depression-Era?

Catherine Bergin: Communism and Experiences of Race

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/chester-himes-ralph-ellison-richard-wright-communisme-et-experiences-vecues-de-la-race-un-entretien-avec-catherine-bergin/

- In the introduction of the book you have edited, African American Anti-Colonial Thought, 1917-1937, you write that one of the reasons why you choose to focus on this specific period is because “[t]his historical period also saw a novel relationship between African American activists and the Left in the USA, a relationship that strongly informed the race politics of the time” (p. 2). Could you please explain this point?

Kylie Jarrett: Feminism, labour and digital media

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/des-salaires-pour-facebooker-du-feminisme-a-la-cyber-exploitation-entretien-avec-kylie-jarrett/

- You recently published Feminism, labour and digital media : the digital housewife[1], in which you tried to frame the booming empirical research about digital technologies on the ground of post-operaist marxism and digital labour theories on the one hand, and of feminism on the other. What is decisive in the contribution of the first two ? Why should we put political economy, and even more specifically the concept of labour, at the core of our understanding of digital mediations?

Christian Fuchs: Internet and Class Struggle

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/internet-et-lutte-des-classes/

- Your book Digital Labour and Karl Marx offers an inspiring analysis of things we daily do, such as browsing on the internet, using social media... What motivated you to develop a Marxist theory of communication?

John Sexton: The Congress of the Toilers of the Far East

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/le-congres-des-travailleurs-dextreme-orient-entretien-avec-john-sexton/

- Could you please tell us about the origins of the Congress of the Toilers of the Far East (1922)? Why was this Congress much smaller than the Baku Congress (1920)? How can one explain that there were around 37 Nationalities in Baku but that the majority of the delegates during the Congress of the Toilers of the Far East came only from four countries (China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia)?

Stefan Kipfer: Gramsci as geographer

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/gramsci-geographe-entretien-avec-stefan-kipfer/

- Your research interests include a recurrent focus on space, specifically urban questions as well as the spatial organization of relations of exploitation and domination. Theoretically, you mobilize the works of Henri Lefebvre and Frantz Fanon, but you are also interested in Gramsci’s take on, for example, urbanity and rurality. How do you see the relevance of Gramsci’s analyses for geographical concerns today?

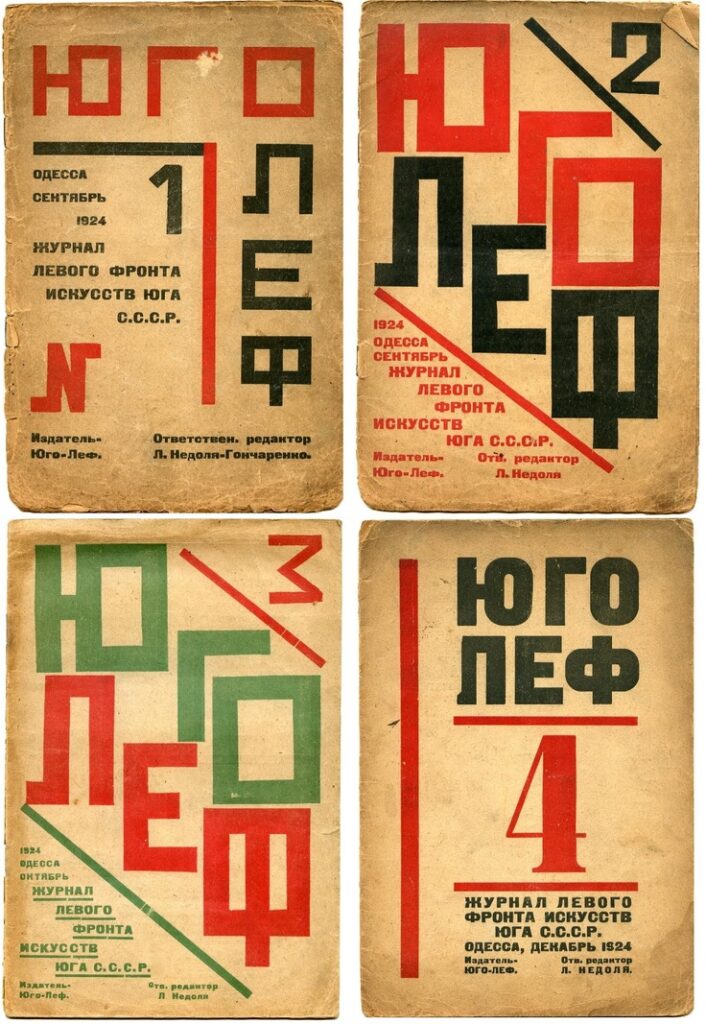

Craig Brandist: Language, Culture and Politics in Revolutionary Russia

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/langage-culture-et-politique-en-russie-revolutionnaire-entretien-avec-craig-brandist/

Craig Brandist is Professor of Cultural Theory and Intellectual History, and Director of the Bakhtin Centre at the University of Sheffield, UK. Specialising in early Soviet thought, his books include Carnival Culture and the Soviet Modernist Novel (1996),The Bakhtin Circle: Philosophy, Culture and Politics (2002) andPolitics and the Theory of Language in the USSR 1917-1938 (with Katya Chown, 2010). Building on the research for his recent bookDimensions of Hegemony: Language, Culture and Politics in Revolutionary Russia (2015), he is currently working with Peter Thomas on a book about Antonio Gramsci's time in the USSR, and on early Soviet oriental studies.

- Could you please expand on the evolution of orientology that emerged at St. Petersburg University at the end of the 1890s and how « ideas [from those orientalists] about empire tended to coalesce around a liberal-imperial perspective » (p. 56)? To what extent did linguistics became an «autonomous discipline » with the 1917 Revolution?

Six points on the eve of the UCU strike

HM editorial board members are currently on strike in their pre-1992 UK universities over the private financialisation of pensions.

Editor Jamie Woodcock is an academic worker with a few institutions at present, some of which will be on strike starting the 22nd February 2018. He is a member of two trade unions: UCU and theIWGB. The following six points are intended as a brief reflection before the strike [this post was originally published byNotes From Below on 21 February 2018]:

1. The strike is about pensions!

The UCU is planning 14 days of strike action to oppose changes to the USS (Universities Superannuation Scheme) pension. For many workers, pensions are now limited to the legal requirement from employers. Others are denied pensions by using bogus self-employment status. At present, academic workers have a relatively good pension scheme.

There are two points worth noting about this pension scheme. First, while employers pay into the scheme, so do we. Second, the pension scheme has already partly been sold out. This means that early career academic workers already get a worse deal in USS. Instead of their pension being based on their final salary at retirement (which would mean more) it is now based on their career average (which would be less). Furthermore, academic workers in post-92 institutions are on a different pension scheme.

The changes are being forced through by Universities UK and supported by the Chair of the USS Board. They claim that the pension scheme is running at a deficit. Their valuation has been challenged and is based on a worst case scenario of all universities going bust at the same time. Their proposal is to move away from a “defined benefit” scheme, in which you can predict what your pension will be worth at retirement. Instead it will become a “defined contribution” scheme. Rather than a guaranteed amount, it means contributions are placed into an individual portfolio of stocks and shares, exposing them to risk. This means the benefit could reduce as the investment is gambled.

So, why should other people care about this? Public sector pensions not some sort of “privilege”, they are deferred earnings. Attacking these pensions has the potential to undermine private sector pensions too. While we are defending our pensions, they are something that all workers should receive. Within universities, reducing the cost of pensions opens up the possibility of further privatisation. Lower costs make universities a more attractive opportunity for private ownership.

2. The strike is not about pensions!

Universities have changed. When I finished my PhD, a professor of employment relations asked me where I would be taking up my lectureship. At the time I was working at three different universities in London, stringing together short term, hourly paid contracts. I had to explain – to a professor of employment relations – that work had changed for many in the university.

Over 50% of academic workers are now employed on precarious contracts. For example, many contracts are for only one year (sometimes excluding the summer). These can be extended, but not beyond three years. This is because the offer of a fourth year provides some scant employment protection.

Conditions are getting worse. There has not been an above inflation pay rise in universities since 2009. (As a side note, this was during my undergraduate degree. This means that during my entire time in Higher Education, the pay of academics has declined). Estimates put this loss in pay at 14.5% in real terms.

As we have written about elsewhere in Notes from Below, workers’ inquiry can be used to investigate and organise in the university. There is a long list of other issues including: precarity, pay (and the gender pay gap), institutional sexism and racism, workload modelling that bears little if any relationship to reality, stress and bullying, the pointlessness of REF (a way of comparing research outputs) and TEF (the teaching version), the attempt to make academics act like border officials, racist policies like Prevent, and so on.

Legally, this strike is about pensions, but it is also clearly about so much more. It is about all the other issues we know are happening at universities, but have not fought over. This is because we were told the big fight over pensions was coming.

For many, the strikes are about so much more than pensions. This is despite the fact that UCU is not officially contesting anything else.

3. We need to do the 14 days of strike action!

The UCU balloted members in 61 Universities and laid out a plan of strike action starting on the 22nd of February. The schedule is as follows:

First week: strike on Thursday 22nd and Friday 23rd of February

Second week: Monday 26th, Tuesday 27th, and Wednesday 28th of February

Third week: Monday 5th, Tuesday 6th, Wednesday 7th, and Thursday 8th of March

Fourth week: Monday 12th, Tuesday 13th, Wednesday 14th, Thursday 15th, and Friday 16th of March

The strike, withdrawing our labour, remains a key way we can fight our employers. This is also being accompanied by something called action short of a strike (ASOS). This involves working to contract, refusing to take on voluntary duties, etc. At some universities, there is now a threat that failure to do all of this additional work (outside of the contract) will result in full deduction of pay. This reveals how much unpaid work academic workers are expected to do.

At universities across the country, branches are planning to do more than withdraw their labour for the day. For example, planning teach outs and a demonstration in London on the 28th of February.

Between branches, activists are organising to coordinate action. You can join the Facebook group here.

4. We need to do more than the UCU strike!

In my last job, I would usually only come onto campus to teach. When I was not teaching, my only interaction with the university management was by email. This was regardless of whether I was physically “there” or not. While away from campus I spend my time on research. This makes striking in universities feel different to many workplaces. It is therefore worth briefly considering the academic labour process and how it can be effectively disrupted.

If we isolate out the activities of the university to just academics (which while useful for now, is also a terrible idea – and I’ll return to this in the next paragraph), what is the aim of the work? The aim is twofold. First, to sort potential workers for the job market. This involves teaching, marking, and awarding of degrees. Second, doing “research.” This is something that most of the time does not matter to the university until the REF. This is an expensive and subjective attempt to “measure” the quality of work approximately every five years. In addition to this, academic workers have to do increasingly larger amounts of administrative work.

So what does this mean for effective strike action in the university today? During a previous dispute, my local branch asked the national UCU if we could organise an email boycott as part of the strike. They replied by email (without any irony) that this would not be possible as it would be “too effective.” As many precarious academic workers have no permanent offices, this means it is often management’s only way to communicate.

The university is much more than just the academics. My last department employed more support staff than academics. This includes technical staff, cleaners, groundskeepers, catering, and so on. It would take many days (and perhaps even weeks) for my employer to notice I had withdrawn my labour. But when cleaners strike the effects are felt the next day. While academics have seen their conditions eroded over the last ten years, the cleaners in central London have been a beacon of precarious workers struggle.

Many of the plans for the strike at different universities sound exciting, but imagine a strike in which all the workers of the university walk out. For many academics, this would mean getting to know the other workers upon which the university relies. It means seeing that while we have relatively good conditions, we also have the freedom to organise not found in many workplaces.

5. We need the UCU!

The UCU is a large union with an established structure and resources. It is involved in national pay bargaining - the setting of rates of pay across every university in the country. This means collectively negotiating between the union and the all of the employers. While it has not used this capacity in a long time, this means the UCU can organise national strike action with all universities at once.

UCU is the largest trade union for academic workers. In many university departments the majority of academic workers are members. This means branches can act as a focus for workplace concerns and organising in universities.

Many branches across the country spend huge amounts of time and resources on case work. This involves supporting vulnerable workers against management. The expertise within the union has been developed over many years, with some successes on a local level and a layer of militant activists.

6. We need more than the UCU!

This strike is a test of the UCU. Previous struggles – particularly around precarious contracts – have been deliberately held back to wait for the fight over pensions. The result of this strike will be decisive.

There is much we can learn from the alternative unions in London. IWGB and UVW provide powerful examples of successful organising in universities. This is why I organise in my workplace and am a member of both UCU and IWGB. At Senate House (part of the University of London), IWGB members will be walking out on the first day of the UCU strike. This is the kind of action we need to win the dispute.

Rather than starting with the union - in this case UCU - we need to begin instead with the workplace. By understanding how we work, we can best plan to disrupt the workplace - particularly by organising with other workers in the university. It is this kind of organising that can challenge our employers and build power.

Although their work was very different to contemporary academic workers, the Clyde Workers’ Committee laid out an important principle for the relationship between workers and the union:

We will support the officials just as long as they rightly represent the workers, but we will act independently immediately they misrepresent them. Being composed of Delegates from every shop and untrammelled by obsolete rule or law, we claim to represent the true feeling of the workers. We can act immediately according to the merits of the case and the desire of the rank and file.

As the strike begins, this is an important principle to keep in mind. We have voted for strike action to defeat the pensions changes, anything less is a failure.

On the eve of the UCU strikes we should all be ready to fight as hard as possible for victory – but soon after we need to have a discussion about what happens next.

At Notes from Below, we will be on picket lines handing out “the University Workers” bulletin, which can be found online here. If you want to join a picket line, there is information about Senate Househere.

Jamie Woodcock is a researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute, author of Working the Phones, and a member of the Class Inquiry Group. Twitter:@jamie_woodcock.

The Explanatory Value of the Theory of Uneven and Combined Development

Susan Dianne Brophy has a PhD in Social and Political Thought (York University - Toronto, Canada) and is currently an Assistant Professor in Legal Studies (St. Jerome's University - Waterloo, Canada). For more info see https://uwaterloo.ca/scholar/s3brophy. An earlier draft of this paper was presented at the HM London 2016 conference.

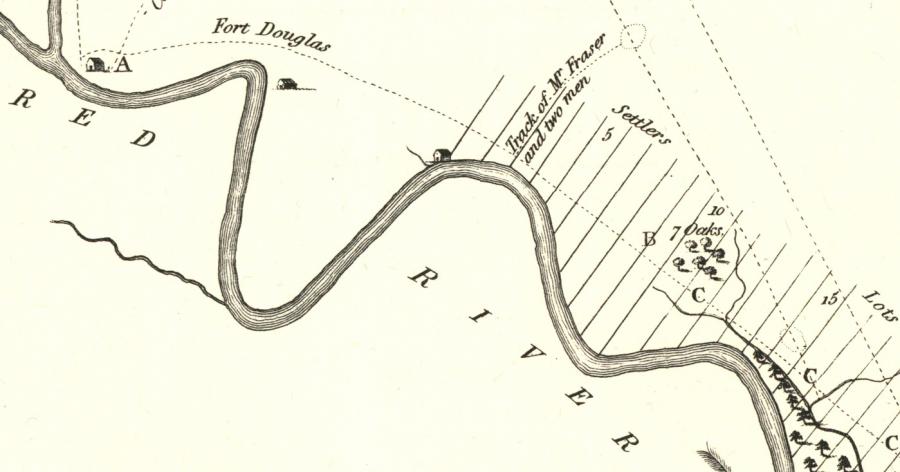

Picture: “Red River Settlement 1818 [1910]” by Wyman Laliberte is licensed underCC BY 2.0 / Cropped from original

Capitalism does not evolve in either a linear or uniform way. Unevenness, exemplified by different levels of market penetration or industrial development, may be present in a single jurisdiction, while non-capitalist elements may combine with capitalist forces of production to varying degrees. Articulated in this way, the uneven and combined development (UCD) of capitalism is a demonstrable fact, one so assumed as a given that some hold it up as a ‘law’ of development.[1] So commonsensical is UCD that in the pages of New Left Review two decades ago, Justin Rosenberg pondered why an historical perspective that offers such ‘retrospective simplicity’ took as long as it did to emerge in the first instance.[2] This supposed simplicity, however, points to another curiosity: how can the manifestly obvious also (and still) be so contentious?

Rosenberg’s instincts in 2013 were right. To answer this question means to journey into the philosophical wilds where this concept first took root;[3] if one wishes to study the philosophical grounds of UCD, the terminus is not Trotsky alone,[4] but the broader philosophical foundation of Marxism: dialectical materialism.

Debates about UCD continue today, especially but not exclusively in the arenas of historical sociology[5] and international relations (IR) theory.[6] Among the more interesting disputes are those between Political Marxists (generally proponents of Robert Brenner’s class-focused approach to the transition to capitalism) such as Benno Teschke,[7] and UCD-proponents in IR, such as the recent work by Alexander Anievas and Kerem Nişancıoğlu.[8] There are two intersecting fault-lines in this debate, one having to do with the temporal scope of UCD, and the other raising questions as to the explanatory value of the concept. Presumably, if we could just agree on whether UCD is a transhistorical law or a characteristic exclusive to capitalism, then we can settle the matter of its substantive utility. However, this quick fix does nothing to solve the underlying tautology, which holds that UCD explains the development of capitalism, but at the same time UCD itself requires further elaboration — or more succinctly, the notion ‘that UCD explains UCD’.[9] Taxed with such deep-seated liabilities, I maintain that a closer look at the dialectical materialist premises of UCD may lead to a resolution. Recast in these terms, the law of UCD is simply an expression of dialectical materialist logic arrived at through the application of an historical materialist methodology. From this philosophical reframing we can draw logical clarity, which will at least dampen the apocryphal renderings of UCD, and maybe even reinstate it as an instructive framework for the study of historical transformation.

Trotsky, to start

Let us turn our attention first to Trotsky, who is among the principal originators of the notion of UCD as an historical law.[10] Even a basic understanding of historical materialism compels us to acknowledge that Trotsky begins with an account of history — the Russian Revolution in meticulous detail — and from that evidence posits UCD as a law of history.[11] The Russian case imprints on him the ‘planless, complex, combined character’ of development,[12] as he describes its historical transformation as occurring in ruptures and ‘leaps’.[13] He observes gaps and disparities, where developmental leaps are not only possible but inevitable under certain conditions; this, he identifies as uneven development. At the same time, he notes the ‘drawing together of the different stages’, where the disassociated becomes unified to establish a new developmental amalgam; this, he identifies as combined development.[14] With leaps, ruptures, disparities, and unevenness, on the one hand, and fusion, interdependency, adaptations, and combination, on the other, we have evidence of the contradictory forces that electrify historical transformation.[15]

Before us is the blueprint for the dominant controversies that persist today, which I only sketch-out here, but will return to in more detail later. First, if Trotsky’s law of UCD is the product of his historical analysis of social relations endemic to capitalism, is it either permissible or wise to assume that the law can also apply transhistorically in a variety of epochs that are characterized by non-capitalist modes of production? Second, even if the law only applies to capitalist development, what is its broader explanatory value beyond the tautological claim that capitalism develops in an uneven and combined manner because...capitalism develops in an uneven and combined manner? Intractable as these disputes appear, we can also see the prospects of a resolution once we embark on a careful dissection of the inner-workings of UCD.

Trotsky arrives at the law of UCD because he understands historical change as essentially conditional, subject to geography and timing — bolting forward or lurching slowly, always in movement. As a law of history it is both generalized and abstract, but as a law of history derived from the application of an historical materialist methodology it reflects the volatility and contradictions of actual social transformation. I think of this as a type of rule of unruliness, which, for Trotsky, anchors two other definitive claims: the rejection of the economic determinism that gives rise to a stagist approach to history,[16] and the theory of permanent revolution. Since remnants of previous eras of production are carried over and come into conflict with new productive means, economic change is revealed as highly contingent and susceptible to an array of internaland external (i.e. international) influences.[17] Revolution, likewise, must then be understood as interminable because no successive phase is ever complete until the class system itself has been decisively overthrown.[18] In unequivocally dialectical terms, ‘the process of development’ is the uninterrupted but nonlinear disintegration and integration of discrete phases wherein disparate facets of historical transformation interpenetrate to comprise a ‘totality’, or more precisely, a ‘differentiated unity’.[19]

Almost by stealth, but in no respect by accident, we have before us the philosophical tenets of dialectical materialism — negation, contradiction, and synthesis — each of which serves a common logical imperative: what the adept-but-underrated materialist dialectician, Frantz Fanon, referred to as the ‘perpetual interrogation’ of the relation between the concrete and the abstract.[20] I view the law of development that Trotsky advances as an iteration of this dialectical materialist imperative; the two are inseparable, if not synonymous, and to ignore this deep association is to misunderstand the philosophical foundations of UCD. It follows, then, that the most egregious distortions of UCD in contemporary debates result from the lack of attention to (at best), or outright denial of (at worst), this explicit correlation.

Debates adrift

From the divergences in the relative fidelity that scholars insist upon when it comes to Trotsky’s original formulations we can trace a diversity of expectations with regard to UCD. Though I account for only a selection of these offerings, my sampling is enough to showcase both the distortions that characterize contemporary debates about UCD, and the value of a return to dialectical materialism as a riposte.

On the first page of the first chapter of Late Capitalism, Ernest Mandel begins his defense of the law of UCD with a note on the relation between the abstract and the concrete.[21] Almost embarrassed to raise such an elementary consideration, he anchors this section with a quote from theGrundrisse that spans three-quarters of a page. He then offers a deft summary — supplemented by Lenin’sPhilosophical Notebooks — in the form of four rules that serve to guard against over-simplification of Marx’s method: first, the concrete is both the starting focus and the end objective; second, the abstract and the concrete give rise to each other in a process of dialectical progression; third, this manner of progression unifies ‘analysis and synthesis’, keeping intact the mutually constitutive relation between the abstract and the concrete as a ‘unity of opposites’;[22] and fourth, each successive phase of cognition must be ‘tested in practice[23] as a means of validation. With this philosophical logic at hand, he undertakes to comprehend the distinctiveness of late capitalism, first by identifying the laws of capitalism in general.

Mandel’s interpretation of the development of capitalism turns on the law of UCD, which he thinks distinguishes him from those that assume equilibrium as a law.[24] For Mandel, disequilibrium is the ‘essence of capital’;[25] how and to what end surplus-value can be extracted and accumulated in one area is related to how and to what end surplus-value can be extracted and accumulated in another. The ‘juxtaposition of development and underdevelopment’ that Mandel observes leads him to endorse UCD as a law,[26] one that he considers universal insofar as it applies to capitalist development in general,[27] but not transhistorical in the sense that it applies to other non-capitalist epochs. On the surface, we can grant Mandel this differentiation between the universal and the transhistorical; peel back a layer, though, and we see how an abuse of his own rules leads to confusion about the temporal scope of UCD and, by extension, to tautological inferences.

Arguably, Mandel is more concerned with a defense of the abstract laws of capitalism, and of Marxism in general, than with understanding capitalism as a differentiated unity undergoing constant change. This is Chris Harman’s position in his scathing review of Late Capitalism, in which he argues that processes of perpetual change also implicate the laws themselves, and that in failing his own philosophical tenets, Mandel ‘replace[s] explanation by eclecticism’.[28] Once we stop querying the abstractions, they lose validity and become relics that can only be deployed in an eclectic fashion. This may explain what happens to the law of UCD as it becomes a hallmark specific to capitalist development; UCD’s temporal restriction banishes it as an idiosyncrasy of capitalism, in effect hypostatizing the abstraction and dissolving the ‘unity of opposites’ into total identification. When the abstract is assumed as the concrete, the explanatory value of the law of UCD gives way to a tautology: the fact of UCD explains the law of UCD, which is taken as a fact.

What if we just stopped calling the law of UCD a ‘law’, would that not fix the problem? Marcel van der Linden offers this very suggestion. Scientific laws serve a predictive purpose, but van der Linden is not convinced that the ‘law’ of UCD can achieve such an outcome with any reliability. He argues, therefore, that the ‘law’ of UCD is ‘insufficiently specific’ and as such, is not a ‘law’ at all.[29] In a way Jon Elster offers a like statement about UCD, but with a more renunciatory flair. Analytic Marxist as he is, to his mind UCD is ‘vapid’, and falls in with other Marxist theories he likewise finds suggestive and elusive.[30] In support of this dismissal, he contends that there is a lack of clarity with respect to how the ‘objective’ elements (i.e. the economic conditions) and the ‘subjective’ elements (i.e. the political or social temperament) would ever combine in such a way that would allow us to predict where and how a communist revolution would occur. Whereas van der Linden maintains that once we rid the yoke of ‘law’ from UCD, we can better examine the social relations that occasion ‘historical leaps’,[31] Elster rejects UCD altogether because of its meagre predictive value. Yet both challenge UCD as a static abstraction, and both begrudge the abstraction because it loses sight of the concrete.

But no, we cannot just to strip the term ‘law’ from our understanding of UCD because in doing so we risk going too far in the other direction: that is, sacrificing the dialectic for materialism and undermining the logic that brought us to UCD in the first place. Elster would be fine with this outcome, but that only goes to show how closely identified UCD is with dialectical materialism to start with. Perhaps the answer is to keep the notion of the ‘law’, but extend its application to non-capitalist epochs, and in doing so, arrive at a less restrictive understanding of the abstract law — one that allows for the further differentiation of the concrete. This is what Rosenberg brings to IR theory.

For Rosenberg, UCD serves his broader aim, which is to introduce a more systematic understanding of the history of social transformation to the field.[32] He suggests UCD as a way into the debate because it brings ‘the social’ to bear on ‘the international’ at the same time that it offers ‘a general abstraction of the historical process’ (read: UCD as not exclusive to capitalism).[33] Related to the second point, he argues that to treat UCD as an exclusively capitalist ‘side-effect’ is to distort Trotsky’s original formulation, which presents UCD as an historical law of a more temporally-generalizable scope.[34] In response to Rosenberg’s interpretation of Trotsky, Alex Callinicos (arguably in a manner reminiscent of Mandel) makes the case for a ‘mode-of-production’ approach, drawing on concepts fromCapital to accentuate the specific ways that capitalism emerges in certain geographies and periods.[35] Although he does acknowledge that UCD, per Trotsky’s vision, resists economic essentialism,[36] this admission does not protect Callinicos himself from the charge that he approaches UCD in ‘exclusively economic terms’.[37] Overall, this productive exchange between Callinicos and Rosenberg in IR theory reflects the more general debate over UCD. Applied in one manner, UCD as an analytical framework can account for ‘the social’ and is stalwart against reductive economism. From another angle, it over-generalizes and as such is insufficiently explanatory, rendering its applicant unable to account for the particularities of how capitalism evolves.

The 2008 Callinicos/Rosenberg exchange led to a special section on UCD published by the Cambridge Review of International Affairs in 2009. Here, we tread the same disputed terrain as before, but with a concerted interest in the contentiousness of Rosenberg’s reading of UCD as tranhistorical. In the lead essay, Neil Davidson argues that the UCD that Trotsky speaks to is not the transhistorical UCD that Rosenberg identifies with, but is rather a particular moment in Russian history that ‘only arrives with capitalist industrialisation’.[38] Sam Ashman concurs, attesting that capitalism engenders a specific type of unevenness that is not in fact transhistorical, so by deploying UCD as a transhistorical law we lose sight of the unique facets of capitalism that gave rise to UCD in the first place.[39] A like assessment comes from Jamie C. Allinson and Alexander Anievas, who claim that it is only possible to arrive at UCD once one acknowledges that the drivers in capitalist expansion (competition and surplus-value) compel as much.[40] This starting point necessarily limits the transhistorical applicability of UCD, although they find some worth in how UCD links pre-capitalist and capitalist history. That Anievas in particular finds value in UCD is evidenced by the monograph he later co-authors with Nişancioğlu,How the West Came to Rule. The authors identify three applications of UCD: as an abstract law, as a methodology, and (their preferred approach) as a theory,[41] and argue — in line with Rosenberg’s view — that the best part of UCD is Trotsky’s promotion of the international as a force in historical transformation.[42]

Among the more acerbic commentaries on Rosenberg’s approach to UCD is Teschke’s from 2014. Teschke is skeptical of the IR twist on UCD, indicting it as the regrettable offspring that resulted from the union between neo-realism and structuralism.[43] For him, the collapsing of UCD as a law and as a theory in IR undermines its explanatory promise by ensconcing it in abstraction,[44] an eventuality he finds insupportable because it violates a key tenet of Marx’s dialectical method,[45] namely the ‘perpetual interrogation’ of the relation between the abstract and the concrete. Indeed, what Teschke finds disconcerting is that which others have already flagged: the hypostatization of the abstract law that both loses sight of the concrete and leads to a tautology. I would add, however, that in what is otherwise a trenchant study, Teschke’s dismissal of UCD is disingenuous. He wrests any trace of dialectical materialism from his understanding of UCD, inserts a tautology in the resultant void, and declares that ‘it remains unclear what drives uneven and combined development’.[46] The transhistorical scrap that is left over is incapable of identifying the productive role of ‘political agency’ in historical development,[47] and as such, should be rejected.

Taken solely as an abstract law, the simplicity of UCD undermines its anticipated explanatory value. At first blush, UCD purports to explain the development of capitalism by providing a template for understanding economic change; however, this template proves insufficient, leading to the realization that the concept of UCD itself requires further elaboration. Teschke refers to this as the inescapable ‘flat tautology’ of UCD.[48] His diagnosis exposes the terminal flaw of UCD; yet this palliative assessment is antithetical to dialectical materialism and is a misleading consignment of the explanatory value of UCD. Specifically, Teschke treats as synonymous the notion of UCD as an abstract law and historically-differentiated UCD, which amounts to a desertion of dialectical materialist methodology that leads to the tautological trap. Far from inevitable or fatal, the trap is of his own making: UCD can be diagnosed as a ‘flat tautology’ only when the mutually constitutive dialectic between the abstract and the concrete has been flattened.

As I have shown, some cast the law of UCD as a transhistorical, overly-generalizing imposter that is beyond redemption, yet when we repatriate UCD back to the realm of dialectical materialism, such grim diagnoses are insupportable for two reasons. First, UCD as an abstract law is the logical product of the dialectical materialist logic in practice, and since this logic ‘perpetual interrogation’ cannot abide such a tautological assertion,[49] those who banish UCD on the grounds of its tautological character also forsake its dialectical materialist essence. Second, UCD is tautological only if it remains within the confines of a static abstraction. Since the duty of the dialectical materialist is to concretize abstractions (and vice versa), UCD must be understood as a clarion call for further analysis, or as Anievas and Nişancıoğlu explain, it is an undertaking that ‘proceeds through a series of descending levels of abstraction, further approximating, and reconstituting in thought, empirical reality along each step of the way’.[50] We are needlessly drawn down the tautological path when we abandon the core of the dialectical materialist philosophy, namely by mistaking the simple abstraction for a concrete category.[51] Instead of deploying these concepts interchangeably toward self-defeating ends, we should be mindful of the mutually constitutive relation between the law of UCD as a simple abstraction and historically-differentiated UCD as a concrete category.

A riposte

While Teschke is wary of the ‘circular result that UCD explains UCD’,[52] it is an essential principle in dialectical materialist analysis that we should not take comparable concepts as identical, fixed abstractions, as Trotsky reminds us, ‘in reality “A” is not equal to “A”’.[53] With reference to measurements of sugar, he explains that a pound of sugar on one scale is not equal to a pound of sugar measured on a more exacting device. Absolute correspondence requires formalism and fixedness, but where there is no change (temporal or otherwise), there is no life or ‘existence’.[54] Meanwhile, ‘[d]ialectical thinking analyses all things and phenomena in their continuous change, while determining in the material conditions of those changes that critical limit beyond which “A” ceases to be “A”’.[55] From this perspective, the diagnosis of UCD as a ‘flat tautology’ comes into focus as a red herring: UCD is not equal to UCD, unless understood undialectically, and by extension, inconsistently with respect to its originating mode of engagement.

A strong case against a temporally-contained conception of UCD comes from Anievas and Nişancıoğlu, who see the tentacles of UCD as extending beyond European capitalism.[56] In more philosophical terms, however, this persistence of the debate about whether or not UCD is transhistorical stems from the lack of a more apt demarcation between UCD as a simple abstraction versus a concrete category, and is complicated by divergences into formalism that accompany the insistence that UCD is tautological. By focusing on this relation between the abstract and the concrete in more detail, however, we can excavate the entwined roots of dialectical materialism and UCD, which allows us to re-assess what we can reasonably expect from UCD in the study of historical transformation.

We know that fixed abstraction freezes the dialectic and breeds tautology by mistaking the abstract for the concrete, but the way out of this bind requires more than the interrogation of abstraction through concretization. Trotsky insists that the drive to concretize the abstract does not give rise to categorical verdicts on social relations, but in fact that ‘the more concrete the prognosis, the more conditional it is’.[57] For example, we can have, on the one hand, labour as an undifferentiated (abstract) category, and on the other hand, wage labour as a more historically-differentiated category. Although the latter is more historically-specific, it is still an abstract and in no way a settled category;[58] we are only in “the process of ‘true abstraction”’,[59] and not at the end point of our analysis. Indeed, as we proceed with an assessment of historical development, our truth claims about the concrete become increasingly relative. However, we should not confuse this with a descent into pure relativism, doing so would come at the cost of losing the constitutive connection to totality. As Lenin explains, dialectical materialist logic guards against this degeneration because it ‘recognises the relativity of all our knowledge, not in the sense of denying objective truth, but in the sense that the limits of approximation of our knowledge to this truth are historically conditional’.[60] Through the unity of ‘analysis and synthesis’, we keep the differentiation between the abstract and the concrete intact, compelling us toward the interrogation of our very understanding of totality. What we have, then, is a dialectic between relative truth and objective truth, wherein our knowledge of objective truth is conditional, yet objective truth exists unconditionally.[61] In this sense, our comprehension of the unconditional and objective occurs through our comprehension of the conditional and relative, and vice versa.

More than just concretizing the abstract, therefore, it is also a matter of taking what we think of as concrete and holding it up to further analysis, that is, abstracting the concrete. For instance, the contract, as a simple abstraction, appears across various epochs. However, the specific type of contract that is integral to the capitalist mode of production can only be understood as developing its unique form in relation to other specific historical developments. When the simple abstraction is interrogated according to the particulars of a given time and place, it is subjected to ‘the process of ‘true abstraction’’, where we have the union between ‘synthesis’ and ‘analysis’. This involves placing the specific historical developments of the capitalist contract (such as who is allowed to enter into contract at a given time and place) against the abstract concept of the contract (with its early roots in the swearing of oaths).[62] The abstraction interpenetrates the concrete, and although the two categories remain distinct, the historical development of the contract in its capitalist form both assumes and negates the contract as a simple abstraction. In this transformation, the contradictory elements can remain intact to varying degrees, which allows us to comprehend how the contract, effectively a testament to enmity in capitalism, remains connected to the notion of the contract as an expression of fealty in other epochs.

An example that better evinces these dialectical connections is the early settler-colonial context of Canada. With the founding of the first settlement on the prairies in 1812 at Red River (in present-day Manitoba), the feudal contract that bonded servants to the fur trading Hudson’s Bay Company was transforming as some servants became land-holding settlers. For this to occur, the servant had to be ‘set free, to work for himself’ and to ‘be charged as a debtor’ to the company’s store, adopting prototypical bourgeois freedoms along the way.[63] But this was not a simple tale of how the fealty of the servant’s feudal contract was negated by the so-called ‘freedom’ of the settler’s debt-based contract. Crucially, this transformation portended changes to Indigenous peoples’ freedom. The synthesized freedom that was at the core of the settler’s new contractual position was an abstract condition shaped by the reality of what it meant to be a debtor and by the fact that landownership entailed compromises to the freedom of certain Indigenous peoples. The synthesized freedom of these Indigenous peoples, in turn, reflected the reality that their signatures were needed on treaties in order to legitimize the dispossession of land.[64] Seen as ‘unacquainted with control and subordination’, their freedom was recognized by colonial agents in instances that facilitated contract-based relations of dispossession.[65] At Red River at around 1812, therefore, contract-making was a vehicle of change, but the actual process was interpenetrated by abstract concepts of freedom and racial and class realities.

To begin to comprehend the totality of the transformations is to identify a historically-specific manifestation of UCD, which requires close scrutiny of contradictions, negations, and syntheses occurring at a particular historical site and time. In the example provided, the abstract and undifferentiated dimensions of the contract become comprehensible when the relative and historically-specific facets are attended to, which in turn illuminates how abstract elements are differentiated though no less constitutive in actual contractual relations. Even with this brief illustration, we begin to see the uneven and combined dynamics of a specific transformative period, which clarifies the constitutive relation among the contract as an undifferentiated construct, the bourgeois-type freedoms associated with capitalist contracts, and the contract in a still more specific early settler colonial context. By progressing through ‘descending levels of abstraction’, it becomes possible to connect but differentiate the contract as a fixed abstraction in relation to historically-specific practices of contract-making. At the same time, we see how UCD as an abstract, general law and UCD in a more concrete historical context are mutually constitutive, but not identical.