Notes on Late Fascism

Alberto Toscano on Fascism

This paper was first delivered as a seminar in February 2017 at Simon Fraser University. The author thanks Clint Burnham for the comradely hospitality and the participants for their critical engagement. A Greek translation can be found here.

Alberto Toscano is Reader in Critical Theory and co-director of the Centre for Philosophy and Critical Thought at Goldsmiths, University of London. He is the author of Cartographies of the Absolute (2015), The Theatre of Production: Philosophy and Individuation Between Kant and Deleuze (Palgrave, 2006) and Fanaticism: On the Uses of an Idea (Verso, 2010) as well as the translator, most recently, of Alain Badiou’s Logics of Worlds(Continuum, 2009) and The Century(Polity, 2007). He also edits the Italian List for Seagull Books and is a longstanding member of the HM editorial board.

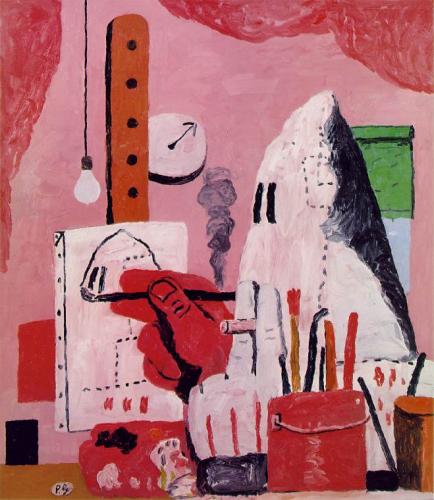

Image: Philip Guston, The Studio, 1969

Those who find themselves living in times of crisis and disorientation often seek guidance in analogical thinking. The likeness of one conjuncture with another promises the preparedness necessary not to be found wanting again, to avert the culpable errors of precursors unarmed with foresight. As a striking example of this recourse to analogy, among countless ones that have circulated before and after Trump’s grotesque coronation, consider this diagnosis by Franco Berardi ‘Bifo’, from a post on Yannis Varoufakis et al.’s DiEM25 page, entitled ‘National-Workerism and Racial Warfare’, published on November 10, 2016, and reprised in his intervention at a conference in Vienna this December under the title ‘A New Fascism?’, also featuring interventions by Chantal Mouffe and the Hungarian dissident and communist philosopher Gáspár Tamás:[1]

As they did in 1933, the workers have revenged against those who have long been duping them: the politicians of the “democratic” reformist left. … This ‘left’ should be thrown in the dustbin: they have opened the way to Fascism by choosing to serve financial capitalism and by implementing neoliberal “reforms”. … Because of their cynicism and their cowardice they have delivered people into the hands of the corporations and the governments of our lives. In so doing, they have opened the door to the fascism that is now spreading and to the global civil war that now seems unstoppable. … The white worker [sic] class, humiliated over the last thirty years, deceived by endless reformist promises, impoverished by financial aggression, has now elected the Ku Klux Klan to the White House. As the left has taken away from the hands of the workers the democratic weapons of self-defence, here comes the racist version of the class warfare.[2]

The analogy of fascism – itself inextricably entangled with its infrastructural pair, the analogy of economic crisis – is my starting point here. I don’t wish directly to explore the cognitive or strategic power of such an analogy, either in the present moment or in earlier iterations, gauging how it may allow us to see and act, but to use it as an occasion to reflect on what some philosophically-oriented theories of fascism advanced in the twentieth century may indicate about the contemporary nexus of politics and history, often by way of determinate dis-analogies. So, my aim will not be to adjudicate the question ‘Is this fascism?’, but rather to discern some of the effects of projecting theories of fascism onto the present, perhaps learning something from their refraction.

Very provisionally, I think they allow us to confront the peculiarity of a fascism without movement, without utopia; a fascism shorn of what Bloch called non-contemporaneity, and Bataille termedhetereogeneity; a fascism that is not reacting to the threat of revolutionary politics, but which retains the racial fantasy of national rebirth and the frantic circulation of a pseudo-class discourse. I also want to suggest that the latter is best met not by abetting the sociologically spectral figure of the “forgotten” white working class, but by confronting what collective politics means today, in the understanding that accepting this racialized simulacrum of a proletariat is not a stepping stone towards class politics but rather its obstacle, its malevolent ersatz form. The aim then is to sketch out, for collective debate and dispute, something like the elementary aspects of a pseudo-insurgency – with the caveat that a pseudo-insurgency was in many ways what the murderous fascism of Europe’s interwar period embodied.

For all of their disputes over the proper theoretical approach to the surge of fascism after the cataclysm of World War 1, most Marxist theorists at the time approached the phenomenon at the interface of the political and the economic, seeking to adjudicate the functionality of the fascist abrogation of liberal parliamentary democracy to the intensified reproduction of the conditions for capitalist accumulation.[3] This entailed identifying fascism as a ruling-class solution to the organic crisis of a regime of accumulation confronted by the threat of organised class struggle amid the vacillations of an imperialist order, but also recognising, at times, the contradictions between the autonomy or primacy of the political brutally asserted by fascist movements and the possibility of a reproduction of the capitalist mode of production – whence the debates of the 1930s and 1940s, especially instigated by the work of Frankfurt School theorists like Friedrich Pollock and Franz Neumann, over the viability ofstate capitalism, debates which contemporary historical work, such as Adam Tooze’s impressiveWages of Destruction, continues to illuminate. Without discounting the tactical alliances that sundry sectors of the US capitalist class may make with the Trump administration (from cement to private security, oil to cars), there is little at present,especially in what concerns any organised challenge to capitalist hegemony, which to my mind warrants the analogy of fascism in this respect – not least in light of widespread corporate protestations, the comparative attraction for capital of Hillary Clinton-style socially-conscious neoliberalism for the maintenance of social peace and profitability, the enigma of protectionism and so on.

The intensely superstructural character of our present’s fascistic traits seems instead to warrant looking elsewhere. Many have already noted the insights that may be mined from the psycho-social inroads that the Frankfurt School (again) made into the phenomenon of fascism, from the writings of Fromm, Marcuse and Horkheimer on petty-bourgeois sadomasochisms in theirStudies on Authority and the Family to the postwar Studies on Prejudice series, with its compendious empirical inquiries into the authoritarian personality. I’ll return to these later, to reflect on some of Adorno’s insights on mass psychology and narcissism, but I want first to try and think with one of the most heterodox entries in the interwar philosophical debate on fascism, Ernst Bloch’sThe Heritage of Our Times. This protean, fascinating and unsettling work – which Walter Benjamin once likened with pejorative intent to spreading wonderfully brocaded Persian carpets on a field of ruins[4] – contains a central, and justly famous, reflection on ‘Non-Contemporaneity and the Obligation to its Dialectic’. Like Bataille, if in a very different register, it was not at the level of political instrument or psychic pathology but at that of perverted utopian promise that Bloch approached fascism. Notwithstanding the crucial elements this occluded from his view,[5] this angle of vision allowed Bloch to identify its popular energising features, ones which, in his view, its Marxist and communist counterpart had failed effectively to mobilise. Underlying Bloch’s argument is the idea that thesocius is criss-crossed by plural temporalities; the class structure of modern society is shadowed by multiple cultural and historical times that do not exist synchronously. The racist, conspiratorial occultism of the Nazis taps this lived experience of uneven development:

The infringement of ‘interest slavery’ (Zinsknechtschaft) is believed in, as if this were the economy of 1500; superstructures that seemed long overturned right themselves again and stand still in today’s world as whole medieval city scenes. Here is the Tavern of the Nordic Blood, there the castle of the Hitler duke, yonder the Church of the German Reich, an earth church, in which even the city people can feel themselves to be fruits of the German earth and honor the earth as something holy, as theconfessio of German heroes and German history … Peasants sometimes still believe in witches and exorcists, but not nearly as frequently and as strongly as a large class of urbanites believe in ghostly Jews and the new Baldur. The peasants sometimes still read the so-called Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses, a sensational tract about diseases of animals and the forces and secrets of nature; but half the middle class believes in the Elders of Zion, in Jewish snares and the omnipresence of Freemason symbols and in the galvanic powers of German blood and the German land.[6]

Where the class struggle between capitalist bourgeoisie and proletariat is a struggle over modernisation, the synchronous or the contemporary, both socially and psychically many (indeed most) Germans in the interwar period lived through social forms and psychic fantasies embedded in different rhythms and histories. Mindful that it would be wrong to view any of these as merely primitive, in a country where social relations of production were never actually outside capitalism, Bloch wants to detect the ways in which, when it comes to their fears (of social demotion or anomie) and desires (for order or well-being), these groups are somehow out of sync with the rationalizing present of capitalism – the enlightened space occupied by the mainstream socialist and labour movements. For Bloch, the Germany of the 1930s is a country inhabited not just by disenchanted citizens, workers and exploiters. Crisis has brought ‘nonsynchronous people’ to the fore: declining remnants of pasts whose hopes remain unquenched, easily recruited into the ranks of reaction.

In a sense at once social and psychic, the political conjuncture is torn between the antagonistic and unfulfilled Now of capitalist conflict and the incomplete pasts that teem in its interstices. The collective emotional effect is a ‘pent-up anger’, which the Nazis and their capitalist boosters are able to mine and to exacerbate, while it remains off-limits to a communism whose enlightenmental rationalism risks becoming practically irrational. So it is that the ‘monopoly capitalist upper class . . . utilizes gothic dreams against proletarian realities’. The question of how to relate, intellectually and politically, to the nonsynchronous becomes central, since it is useless to console oneself with the evolutionist just-so story according to which the archaic will gradually be eroded by social and economic progress. ‘[N]ot the theory of the national socialists is serious, but its energy is, the fanatic-religious impact, which does not just come from despair and ignorance, but rather from the uniquely stirring power of belief’, writes Bloch.[7] Though the political strategy of the proletariat must perforce be synchronous if it is to confront the capitalist Now, it is also required to recover and shape the kind of nonsynchronicity from where immemorial and invariant demands of justice stem. Bloch articulates this unfulfilled and ‘unclaimed’ task in terms of the relation between two forms of contradiction: on the one hand, the synchronous and determinate negativity of the organized proletariat; on the other, those ‘subversively utopian’ positivities that have ‘never received fulfilment in any age’. In this regard, Bloch was trying to supplement a thinking of the ‘synchronous’ contradiction between capital and labour and the ‘nonsychronous contradictions’ that implicated classesout of step with the rhythms and sites of capital accumulation (peasants, petty-bourgeoisie, aristocracy, lumpen proletariat, etc.).

As Rabinbach notes, quoting from Heritage:

The contradiction between these temporal dimensions demands what Bloch calls "the obligation to its dialectic," a recognition of complexity which not only focuses on the synchronous, but on the non-synchronous, the multi- temporal and multi-layered contradictions within a single present. For Bloch it is precisely this sedimentation of social experience that creates the intense desire for a resurrection of the past among those groups most susceptible to fascist propaganda. For Marxism the problem is that fascist ideology is not simply an instrument of deception but "a fragment of an old and romantic antagonism to capitalism, derived from deprivations in contemporary life, with a longing for a vague 'other.'”[8]

For Bloch, the point is to identify fascism as a ‘swindle of fulfilment’ – in his wonderful phrase – while taking that urge for fulfilment, and the manner in which it reactivates unfulfilled pasts and unrealised futures, seriously. But is the complex dialectic of ‘salvage’ invoked by Bloch – for whom, it is not just phases of emancipatory élan but also derived “periods of decline when the multiplicity of contents are released in its disintegration” from which one may revitalise a revolutionary heritage – one that we can turn to today? Severe doubt is cast on this possibility by all those critical theories which have emphasised, from the immediate post-war period onwards, the evanescence or obliteration of cultural and temporal difference from the lived experience of advanced capitalist economies.

A ‘postmodern’, ‘one-dimensional’ or ‘administered’ society is defined perhaps above all by this waning of historicity – which may of course be accompanied by the proliferation of its instrumentalised simulacra. An interesting testament to this might be sought in the controversial newspaper articles of the mid-1970s in which Pier Paolo Pasolini, shortly before his murder, sought to articulate the difference between an old and a new fascism. The latter, which for Pasolini was coterminous with a repressively hedonistic neo-capitalism, with its overt and covert mechanisms for utter conformity, was marked by the obliteration of the past, in the form of what he called (in supposed if rather mystifying reference to The Communist Manifesto) an “anthropological genocide”, namely the death of the experiences linked to peasant and ‘popular’ times and forms of life, a “genocide” he would even register in the transformation of bodies, gestures and postures themselves.[9] For Pasolini, the old fascism (and here the reference is strictly to its Italian variant) was incapable of really undoing or transforming – we could say ‘synchronising’ – those deeply embedded lifeways. This was evident in how they re-emerged seemingly unscathed after the death of Mussolini. Contrariwise the total power of contemporary capitalism, to intensively shape and homogenise desires and forms of life, especially under the appearance of difference, choice and freedom, meant the destruction of all the signs of historical unevenness, with all their utopian potentials. In the profoundly pessimistic view of Pasolini, and contra Bloch, there were no pasts left to salvage.

Now, how might we revisit this question of fascism and (non-)contemporaneity in our moment? Perhaps we can begin with an enormous dialectical irony: the fascistic tendencies finding expression in the election of Trump, but also in coeval revanchist nationalist projects across the ‘West’, are seemingly driven by a nostalgia for synchronicity. No archaic pasts, or invented traditions here, but the nostalgia for the image of a moment, that of the post-war affluence of thetrente glorieuses, for a racialized and gendered image of the socially-recognised patriotic industrial worker (Bifo’s national-workerism could also be called anational or racial Fordism, which curiously represses the state-regulatory conditions of its fantasy). To employ Bloch’s terms this isa nostalgia for the synchronous, for the contemporary. The authorised emblem of a post-utopian depoliticised post-war industrial modernity, the industrial worker-citizen, now reappears – more in fantasy than in fact, no doubt, or in the galling mise-en-scène of ‘coal workers’ surrounding the US President as he abolishes environmental regulations – in the guise of the “forgotten men”, the “non-synchronous people” of the political present. If this is a utopia, it is a utopia without transcendence, without any “fanatic-religious” element, without an unconscious or unspoken surplus of popular energies.

Accordingly, just as the non-synchronous dialectic has been transmuted today into the paradoxical non-synchronicity of the synchronous (or the nostalgia for Fordist modernity, the utopia of a post-utopian age), so Bataille’s parallel identification of the dynamic appeal of fascism with its manipulation of heterogeneity (that which is incommensurable with the orderly self-reproduction of capitalist order, whether from below as mass excess or from above as unaccountable sovereignty) requires present correction. The fascistic tendencies of the present contain little if any relationship to such a libidinal surplus, except in the degraded vestigial form of what we could call, by analogy with the psychoanalytic notion of the ‘obscene father’, the ‘obscene leader’. And this too is linked to the absence of one of the key historical features of fascism, namely the revolutionary threat to capitalist order, demanding that homogeneity inoculate itself with excess (or with its simulacrum) in order to survive. As Bataille noted in his essay on ‘The Psychological Structure of Fascism’:

As a rule, social homogeneity is a precarious form, at the mercy of violence and even of internal dissent. It forms spontaneously in the play of productive organization but must constantly be protected from the various unruly elements that do not benefit from production, or not enough to suit them, or simply, that cannot tolerate the checks that homogeneity imposes on unrest. In such conditions, the protection of homogeneity lies in its recourse to imperative elements [the fundamentally excessive character of monarchical sovereignty] which are capable of obliterating the various unruly forces or bringing them under the control of order.[10] (p. 66)

The signal absence of anything like a mass movement from contemporary manifestations of fascism – which is only further underlined by the fact that today’s racial-nationalist right advertises its movement-character at every opportunity – could also be seen as a sign of this lack ofheterogeneity andnon-synchronicity, the palpable absence of theutopian and theanti-systemic from today’s germs of fascism.

To develop this intuition further it is worth exploring in some detail the relevance of the debates over the mass psychology of fascism to the contemporary debate. It was not only Bataille in his intervention, but many members of the Frankfurt School, who saw Freud’s 1922 essay ‘Mass Psychology and the Analysis of the “I”’ as a watershed in the study of the nexus of collective politics and individual desire, not least in its analysis of leadership. The influence of Freud’s text was vast and variegated (see for an interesting contemporary reflection Stefan Jonsson’s work) but I want to consider it via a postwar text of Adorno’s, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’ (1951), which may also be taken as a kind of corrective to the salvage-readings of fascism provided by Bloch and Bataille. The interest of Adorno’s text is only increased by the fact that it relates to research, namely his own participation in the collective research project on The Authoritarian Personality and the book by Löwenthal and Guterman on American fascist agitators,Prophets of Deceit, which have been justly alluded to as illuminating of the Trump phenomenon.[11]

In The Prophets of Deceit, Löwenthal and Guterman draw the following composite theoretical portrait of the American fascist agitator:

The agitator does not confront his audience from the outside; he seems rather like someone arising from its midst to express its innermost thoughts. He works, so to speak, from inside the audience, stirring up what lies dormant there. The themes are presented with a frivolous air. The agitator's statements are often ambiguous and unserious. It is difficult to pin him down to anything and he gives the impression that he is deliberately playacting. He seems to be trying to leave himself a margin of uncertainty, a possibility of retreat in case any of his improvisations fall flat. He does not commit himself for he is willing, temporarily at least, to juggle his notions and test his powers. Moving in a twilight zone between the respectable and the forbidden, he is ready to use any device, from jokes to doubletalk to wild extravagances. … He refers vaguely to the inadequacies and iniquities of the existing social structure, but he does not hold it ultimately responsible for social ills, as does the revolutionary. … The reformer and revolutionary generalize the audience's rudimentary attitudes into a heightened awareness of its predicament. The original complaints become sublimated and socialized. The direction and psychological effects of the agitator's activity are radically different. The energy spent by the reformer and revolutionary to lift the audience's ideas and emotions to a higher plane of awareness is used by the agitator to exaggerate and intensify the irrational elements in the original complaint. … In contradistinction to all other programs of social change, the explicit content of agitational material is in the last analysis incidental—it is like the manifest content of dreams. The primary function of the agitator's words is to release reactions of gratification or frustration whose total effect is to make the audience subservient to his personal leadership. … He neglects to distinguish between the insignificant and the significant; no complaint, no resentment is too small for the agitator's attention. What he generalizes is not an intellectual perception; what he produces is not the intellectual awareness of the predicament, but an aggravation of the emotion itself. Instead of building an objective correlate of his audience's dissatisfaction, the agitator tends to present it through a fantastic and extraordinary image, which is an enlargement of the audience's own projections. The agitator's solutions may seem incongruous and morally shocking, but they are always facile, simple, and final, like daydreams. Instead of the specific effort the reformer and revolutionary demand, the agitator seems to require only the willingness to relinquish inhibitions. And instead of helping his followers to sublimate the original emotion, the agitator gives them permission to indulge in anticipatory fantasies in which they violently discharge those emotions against alleged enemies. … Through the exploitation of the fear of impending chaos the agitator succeeds in appearing as a radical who will have no truck with mere fragmentary reforms, while he simultaneously steers his adherents wide of any suggestion of a basic social reorganization.[12]

How does Adorno seek to theorise this ‘microfascist’ and antagonistic, but ultimately conservative, intensification of a ‘malaise’ that joins the sense of agential impotence to the disorientation of the humiliated individual before the enigmatic totality, here transmuted into conspiracy? He undertakes a detour via Freud’s ‘Mass Psychology and the Analysis of the “I”’. What he finds, especially since it relates to the forms of fascism in a post-war, i.e. post-fascist, context is perhaps more instructive for the present than the interwar philosophical reflection on fascism as a revolutionary phenomenon.

Adorno wishes to move from the agitational devices singled out by Löwenthal and Guterman, ones that have as their ‘indispensable ingredients … constant reiteration and scarcity of ideas’,[13] to the psychological structure underlying them. As Peter E. Gordon has noted, in his very rich review of Adorno’s contributions to reflecting on the Trump phenomenon,[14] Adorno’s reflections are oriented by his understanding of fascism as a phenomenon linked to the crisis of bourgeois individuality, as both psychic experience and social form. Or, in Adorno’s dialectical quip: “[We] may at least venture the hypothesis that the psychology of the contemporary anti-semite in a way presupposes the end of psychology itself”.[15] As for Freud, Adorno observes that he “developed within the monadological confines of the individual the traces of its profound crisis and willingness to yield unquestioningly to powerful outside, collective agencies”.[16] Adorno homes in on the problem of the libidinalbond that fascism requires, both vertically towards the leader (especially in the guise of a kind of play of narcissisms, the follower finding himself reflected in the leader’s own self-absorption) and horizontally, towards the racialized kin or comrade, identifying this as a technical, or psycho-technical, problem for fascism itself. Commenting on the Nazis obsession with the adjective “fanatical” (already the object of a brilliant entry by Victor Klemperer in hisThe Language of the Third Reich) and with Hitler’s avoidance of the role of the loving father, Adorno remarks: “It is one of the basic tenets of fascist leadership to keep primary libidinal energy on an unconscious level so as to divert its manifestations in a way suitable to political ends”.[17] This libidinal energy is of necessitypersonalized as an ‘erotic tie’ (in Freud’s terms), and operates through the psychoanalytic mechanism ofidentification (again, both horizontally and vertically).

At the psychoanalytic level, fascism preys on the contradiction between the self-preserving conatus of the ego and his constantly frustrated desires. This is a conflict that “results in strong narcissistic impulses which can be absorbed and satisfied only through idealization as the partial transfer of the narcissistic libido to the object [i.e. the leader] … by making the leader his ideal he loves himself, as it were, but gets rid of the stains of frustration and discontent which mar his picture of his own empirical self”.[18] What’s more, “in order to allow narcissistic identification, the leader has to appear himself as absolutely narcissistic … the leader can be loved only if he himself does not love”.[19] Even in his language, the leader depends on his psychological resemblance to his followers, a resemblance revealed in the mode of disinhibition, and more specifically in “uninhibited but largely associative speech”.[20] “The narcissisticgain provided by fascist propaganda is obvious. It suggests continuously and sometimes in rather devious ways, that the follower, simply through belonging to the in-group, is better, higher and purer than those who are excluded. At the same time, any kind of critique or self-awareness is resented as a narcissistic loss and elicits rage”.[21]

Yet the factor that more often than not the fascist leader appears as a “ham actor” and “asocial psychopath” is a clue to the fact that rather than sovereign sublimity, he has to convey some of the sense of inferiority of the follower, he has to be a “great little man”. Adorno’s comment is here instructive:

Psychological ambivalence helps to work a social miracle. The leader image gratifies the follower’s twofold wish to submit to authority and to be authority himself. This fits into a world in which irrational control is exercised though it has lost its inner conviction through universal enlightenment. The people who obey the dictators also sense that the latter are superfluous. They reconcile this contradiction through the assumption that they are themselves the ruthless oppressor.[22]

This loss of ‘inner conviction’ in authority is to my mind the true insight of Adorno’s reflections on fascist propaganda, and where it moves beyond Freud, still hamstrung by his reliance on the reactionary psychological energetics of Le Bon’s Psychology of the Crowd. This relates once again to the “end of psychology”, which is to say the crisis of a certain social form of individuality, which Adorno regards as the epochal context of fascism’s emergence. The leader-agitator can exploit his own psychology to affect that of his followers – “to make rational use of his irrationality”, in Adorno’s turn of phrase – because he too is a product of a mass culture that drains autonomy and spontaneity of their meaning.Contra Bataille and Bloch’s focus on the fascism’s perversion of revolution, for Adorno its psycho-social mechanism depends on its refusal of anything that would require the social or psychic transcendence of thestatus quo.

Fascism is here depicted as a kind of conservative politics of antagonistic reproduction, the reproduction of some against others, and at the limit a reproduction premised on their non-reproduction or elimination. Rather than an emancipatory concern with equality, fascism promotes a “repressive egalitarianism”, based on an identity of subjection and a brotherhood of hatred: “The undercurrent of malicious egalitarianism, of the brotherhood of all-encompassing humiliation, is a component of fascist propaganda and fascism itself” – it is its “unity trick”.[23] In a self-criticism of the psychological individualism that governedThe Authoritarian Personality, Adorno now argues that fascism does not have psychological causes but defines a “psychological area”, an area shared with non-fascist phenomena and one which can be exploited for sheer self-interest, in what is an “appropriation of mass psychology”, “the expropriation of the unconscious by social control instead of making the subjects conscious of their unconscious”. This is “the turning point where psychology abdicates”. Why? Because what we are faced with is not a dialectic of expression or repression between individual and group, mass or class, but with the “postpsychological de-individualized atoms which form fascist collectivities”.[24] And while these collectivities may appear “fanatical” their conviction is hollow, if not at all the less dangerous for that. Here lies the “phoniness” of fascist fanaticism, which for Adorno wasalready at work in Nazism, for all of its broadcasting of its own fanaticism:

The category of “phoniness” applies to the leaders well as to the act of identification on the part of the masses and their supposed frenzy and hysteria. Just as little as people believe in the depth of their hearts that the Jews are the devil, do they completely believe in the leader. They do not really identify themselves with him but act this identification, perform their own enthusiasm, and thus participate in their leader’s performance. It is through this performance that they strike a balance between their continuously mobilized instinctual urges and the historical stage of enlightenment they have reached, and which cannot be revoked arbitrarily. It is probably the suspicion of this fictitiousness of their own “group psychology” which makes fascist crowds so merciless and unapproachable. If they would stop for a second, the whole performance would go to pieces, and they would be left to panic.[25]

This potentially murderous “phony fanaticism” differs from that of the “true believer” (and we could reflect on the problem that revolutionary fascists, from National-Bolsheviks to futurists, often posed to their own regimes) in a way that hints towards the crucial reliance of fascistic phenomena on varieties of the “unity trick”, on various forms of fictitious unity. Here Jairus Banaji’s reflections on fascism in India include a key insight, namely the contemporary uses to which Sartre’s reflections on “manipulated seriality” can be put for analysing fascist violence. The fascist “sovereign group” acts by transforming the serial existence of individuals in social life (Adorno’s “postpsychological deindividualised atoms”) into a false totality – be it nation, party or race (and often all three). “Manipulated seriality is the heart of fascist politics”, as Banaji asserts, because it is not justany mass that fascism conjures up (in fact, the fear of the masses was among its originating psycho-political factors, as Klaus Theweleit’s so brilliantly showed in its analysis of the writings of theFreikorps inMale Fantasies), but an other-directed mass that never “fuses” into a group, a mass which must produce macro-effects at the bidding of the group “other-directing” it, while all the while remaining dispersed. This is the problem of fascism (in a different but not unconnected guise to the problem of a depoliticising liberal democracy): how can the many act without gaining a collective agency, and above all without undoing the directing agency of the few (the group)? Banaji insightfully enlists Sartre’s categorial apparatus from theCritique of Dialectical Reason to think through the fascist ‘pogrom’:

The pogrom then is a special case of this ‘systematic other-direction’, one in which the group ‘intends to act on the series so as to extract a total action from it in alterity itself’. The directing group is careful ‘not to occasion what might be called organised action within inert gatherings’. ‘The real problem at this level is to extract organic actions from the masses’ without disrupting their status as a dispersed molecular mass, as seriality. So Sartre describes the pogrom as ‘the passive activity of a directed seriality’, an analysis where the term ‘passive’ only underscores the point that command responsibility is the crucial factor in mass communal violence, since the individuals involved in dispersive acts of violence are the inert instruments of a sovereign or directing group. Thus for Sartre the passive complicity that sustains the mass base of fascism is a serial complicity, a ‘serial responsibility’, as he calls it, and it makes no difference, in principle, whether the individuals of the series have engaged in atrocities as part of an orchestrated wave of pogroms or simply approved that violence ‘in a serial dimension’, as he puts it.[26]

That Sartre saw seriality as crucial to the very constitution of the modern state and its practices of sovereignty, also suggests that the borders between fascist and non-fascist other-direction may be more porous than liberal common sense suggests. Yet we could also say that fascism excels in the systematic manipulation of the serialities generated by capitalist social life, moulding them into pseudo-unities, false totalities.

If we accept the nexus of fascism and seriality, of a politics which is both other-directed and in which ‘horizontal relations’ are ones of pseudo-collectivity and pseudo-unity, in which I interiorise the direction of the Other as my sameness with certain others (Sartre’s analogy in Critique of Dialectical Reason, vol. 1 between everyday racism and the phenomenon of the Top Ten comes to mind here), then we should be wary of analysing it with categories whichpresume the existence of actual totalities. This is why I think it is incumbent on a critical, or indeed anti-fascist, Left to stop indulging in the ambient rhetoric of the white working class voter as the subject-supposed-to-have-voted for the fascist-populist option. This is not only because of the sociological dubiousness of the electoral argument, or the enormous pass it gives to the middle and upper classes, or even because of the tawdry forms of self-satisfied condescension it allows a certain academic or journalistic commentator or reader, or the way it allows a certain left to indulge in fantasies for which ‘if only we could mobilise them…’. More fundamentally, it is because, politically speaking, the working class as a collective, rather than as a manipulated seriality, does not (yet) exist. Endowing it with the spectre of emancipation is thus profoundly misleading, irrespective of statistical studies on those quintessentially serial phenomena, elections.

To impute the subjectivity of a historical agency to a false political totality is not only unwittingly to repeat the “unity trick” of fascistic propaganda, it is to suppose that emancipatory political forms and energies lie latent in social life. By way of provocation we could adapt Adorno’s statement, quoted earlier, to read: “[We] may at least venture the hypothesis that the class identity of the contemporary Trump voter in a way presupposes the end of class itself”. A sign of this is of course the stickiness of the racial qualifierwhite working class. Alain Badiou once noted about the phraseology ofIslamic terrorism that “when a predicate is attributed to a formal substance … it has no other consistency than that of giving an ostensible content to that form. In 'Islamic terrorism', the predicate 'Islamic' has no other function except that of supplying an apparent content to the word 'terrorism' which is itself devoid of all content (in this instance, political).”[27] Whiteness is here, not just at the level of discourse, but I would argue at that of political experience, the supplement to a politically void or spectral notion of the working class; it is what allows a pseudo-collective agency to be imbued with a (toxic) psycho-social content. This is all the more patent if we note how incessantly in both public discourse and statistical pseudo-reflection in order to belong to this “working class” whiteness is indispensable, while any specific relation to the means of production, so to speak, is optional at best. The racialized experience of class is not an autonomous factor in the emergence of fascistic tendencies within the capitalist state; it is the projection of that state, amanipulated seriality, and thus an experiencedifferent in kind from political class consciousness, and likely intransitive to it. In a brilliant and still vital analysis, Étienne Balibar once defined racism as a supplement of nationalism:

racism is not an 'expression' of nationalism, but a supplement of nationalism or more precisely a supplement internal to nationalism, always in excess of it, but always indispensable to its constitution and yet always still insufficient to achieve its project, just as nationalism is both indispensable and always insufficient to achieve the formation of the nation or the project of a 'nationalization' of society. ... As a supplement of particularity, racism first presents itself as a super-nationalism. Mere political nationalism is perceived as weak, as a conciliatory position in a universe of competition or pitiless warfare (the language of international 'economic warfare' is more widespread today than it has ever been). Racism sees itself as an 'integral' nationalism, which only has meaning (and chances of success) if it is based on the integrity of the nation, integrity both towards the outside and on the inside. What theoretical racism calls 'race' or 'culture' (or both together) / is therefore a continued origin of the nation, a concentrate of the qualities which belong to the nationals 'as their own' ; it is in the 'race of its children' that the nation could contemplate its own identity in the pure state. Consequently, it is around race that it must unite, with race - an 'inheritance' to be preserved from any kind of degradation - that it must identify both 'spiritually' and 'physically' or 'in its bones' (the same goes for culture as the substitute or inward expression of race).[28]

Class, in contemporary attempts both to promote and to analyse fascistic fantasies and policies of ‘national rebirth’, risks becoming in its turn a supplement (of both racism and nationalism), stuck in the echo chambers of serialising propaganda. There is no path from the false totality of an other-directed racialized class to a renaissance of class politics, no way to turn electoral statistics and ill-designed investigations into the ‘populist subject’, the ‘forgotten men and women’, into a locus for rethinking a challenge to capital, or to analyse and challenge the very foundations of fascist discourse. Any such practice will need to take its distance from the pseudo-class subject which has reared its head across the political scene. This false rebirth of class discourse is itself part of the con, and another reminder that not the least of fascism’s dangers is the fascination and confusion its boundless opportunism sows in the ranks of its opponents. Rather than thinking that an existing working class needs to be won away from the lures of fascism, we may fare better by turning away from that false totality, and rethinking the making orcomposition of a class that could refuse becoming the bearer of a racial, or national predicate, as one of the antibodies to fascism.

* * *

Preliminary Theses on Late Fascism

Thesis 1 (after Bloch): late fascism is bereft of non-contemporaneity or non-synchronousness – except for the non-synchronousness of the synchronous, the nostalgia for a post-utopian industrial modernity;

T1 Cor. 1 (after Bataille): fascism today is very weak on the heterogeneous surplus necessary to reproduce capitalist homogeneity, both as the “sovereign” (or imperative) level, and that of the “base” (whether lumpen excess or unconscious drives);

T1 Cor. 2 (after Pasolini): the new fascism is a fascism of homogenisation masquerading as the jouissance of difference;

T2 (after Freud and Adorno): the psychic structure of fascism operates through a form of mass narcissism;

T3 (after Adorno): late fascism operates through a performance of fanaticism devoid of inner conviction, though its “phoniness” does nothing to lessen its violence;

T4 (after Adorno): (late) fascism is a conservative politics of antagonistic reproduction;

T5 (after Banaji-Sartre): (late) fascism is not the politics of a class, a group or a mass, but of a manipulated series;

T6: the racialized signifier of class functions in the production and reception of late fascism as a spectre, a screen and a supplement – of the racism which is in turn a necessary supplement of nationalism (a minimal definition of fascism being the affirmation of the supplement, and its more or less open transmutation into a key ingredient of the nation-state);

T7: late fascism is driven by a desire for the state and a hatred of government;

T8: late fascism reacts against what is already a liberal reaction, it is not primarily counter-revolutionary;

T9: late fascism is not consolidated by a ruling class effort to use the autonomy of the political to deal with an external limit of capital but one of the offshoots of an endogenous protracted crisis of legitimacy of capital, in which the political is autonomous more at the level of fantasy than function;

T10: late fascism is a symptom of the toxic obsolescence of the modern figure of the political, namely a “national and social state” in which citizenship is organised across axes of ethno-racial and gender identity, and articulated to labour.

[1]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-QHj7fE2I1o

[2]https://diem25.org/national-workerism-and-racial-warfare/

[3] For a lucid and nuanced introduction to the Marxist debate, from the standpoint of the 1970s, see Anson Rabinbach, ‘Toward a Marxist Theory of Fascism and National Socialism: A Report on Developments in West Germany’,New German Critique, 3 (Autumn, 1974), pp. 127-153.

[4] ‘The serious objection which I have of this book (if not of its author as well) is that it in absolutely no way corresponds to the conditions in which it appears, but rather takes its place inappropriately, like a great lord, who arriving at the scene of an area devastated by an earthquake can find nothing more urgent to do than to spread out the Persian carpets – which by the way are already somewhat moth-eaten-and to display the somewhat tarnished golden and silver vessels, and the already faded brocade and damask garments which his servants had brought.’ Walter Benjamin, Letter to Alfred Cohn of 6 February 1935, cited in Anson Rabinbach, ‘Unclaimed Heritage: Ernst Bloch's Heritage of Our Times and the Theory of Fascism’,New German Critique, 11 (Spring, 1977), p. 5.

[5] As Rabinbach notes, highlighting the significance of Benjamin’s reflections on capitalism, technology and modern spectacle: ‘Bloch emphasizes the continuity between fascism and the tradition embodied in its ideas, but he neglects those elements of discontinuity with the past-elements which give fascism its unique power as a form of social organization-so that its actual links to modern capitalism remain obscure.’ Ibid., p. 14.

[6] Ernst Bloch, ‘Nonsynchronism and the Obligation to Its Dialectics’, trans. M. Ritter,New German Critique, 11 (1977), 26. This text is an excerpt fromThe Heritage of Our Times.

[7] Bloch,The Heritage of Our Times, quoted in Rabinbach, ‘Unclaimed Heritage’, pp. 13–14.

[8] ‘Unclaimed Heritage’, p. 7.

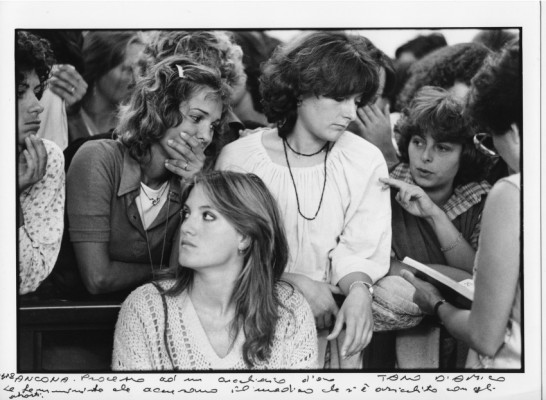

[9] Pier Paolo Pasolini, ‘Il vuoto di potere in Italia’,Il Corriere della Sera, 10 February 1975. The article would later be reprinted inScritti Corsari, a collection of Pasolini’s journalistic interventions published shortly after his death.

[10] Georges Bataille, ‘The Psychological Structure of Fascism’, trans. Carl L. Lovitt,New German Critique, 16 (1979), p. 66.

[11] Perusing the list of ‘themes’ of American fascistic agitation gives an inkling of such illumination: ‘The Eternal Dupes’; ‘Conspiracy’; ‘Forbidden Fruit’ (on the jouissance of the wealthy); ‘Disaffection’; ‘The Charade of Doom’; ‘The Reds’; ‘The Plutocrats’; ‘The Corrupt Government’; ‘The Foreigner’ (with its sub-section ‘The Refugee’).

[12] Leo Lowenthal and Norbert Guterman,Prophets of Deceit: A Study of the Techniques of the American Agitator (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949), pp. 5-9, 34.

[13] Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, inThe Frankfurt School Reader, ed. Andrew Arato and Eike Gebhardt (New York: Continuum, 1982), p. 119.

[14]https://www.boundary2.org/2016/06/peter-gordon-the-authoritarian-person…

[15] Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Remarks on the Authoritarian Personality’ (1958), cited in:https://www.boundary2.org/2016/06/peter-gordon-the-authoritarian-person…

[16] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, p. 120.

[17] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, p. 123.

[18] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, p. 126.

[19] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, pp. 126-7.

[20] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, p. 132.

[21] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, p. 130.

[22] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, pp. 127-8.

[23] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, p. 131.

[24] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, p. 136.

[25] Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’, pp. 136-7.

[26]http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/16825/1/Jamia%20lecture%20%28fascism%29.pdf

[27] Alain Badiou,Infinite Thought: Truth and the Return of Philosophy (London: Continuum, 2003), p. 153.

[28] Étienne Balibar, ‘Racism and Nationalism’, in E. Balibar and I. Wallerstein,Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities (London: Verso, 1988), pp. 54 and 59.

The Eastern Origins of Capitalism?

A Revolutionary Line of March: ‘Old Bolshevism’ in Early 1917 Re-Examined

Contrary to Leon Trotsky's influential account, Bolsheviks in March 1917 opposed the Provisional Government and called for a revolutionary soviet regime.

Eric Blanc is an independent researcher in Oakland, California. He is the author of the forthcoming monograph, Anti-Colonial Marxism: Oppression & Revolution in the Tsarist Borderlands (Brill Publishers, Historical Materialism Book Series).

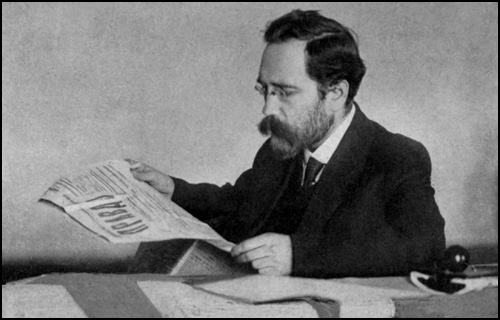

Photo Caption: Lev Kamenev reading Pravda

Intro

In the hundred years since the overthrow of Tsarism, there has been a near consensus among socialists and scholars that Bolshevism underwent a strategic rupture in early 1917. According to this account, the Bolsheviks supported the liberal Provisional Government until Vladimir Lenin returned to Russia in April and veered the party in a radical new direction by calling for socialist revolution and soviet power.

Through a re-examination of Bolshevik politics in March 1917, the following article demonstrates that the prevailing story is historically inaccurate and has distorted our understanding of how and why the Bolsheviks eventually came to lead the Russian Revolution.

That important facts about early 1917 remain obscure one century later in part stems from an ongoing uncritical acceptance of Leon Trotsky’s interpretation of ‘Old Bolshevism’, first articulated in his famous 1924 pamphlet ‘The Lessons of October’. Trotsky claimed that because the Bolshevik leadership had not hitherto advocated socialist revolution in Russia, it had therefore sought only to pressure the bourgeois Provisional Government, rather than overthrow it.[1]

According to Trotsky, ‘Old Bolsheviks’ such as Lev Kamenev and Joseph Stalin ‘took the position that it was necessary to complete the democratic revolution by putting pressure on the Provisional Government’.[2] Adherence to the ‘doctrinaire’ conception of democratic revolution had led ‘inevitably to Menshevism’ in March.[3] Not until Lenin’s April 1917 campaign to convince the party to fight for socialist revolution did the Bolshevik leadership break from this de facto Menshevism, seek to overturn the bourgeois regime, and fight to establish a soviet government.[4]

Were such claims correct, it would indeed be fair to state that Lenin’s April interventions brought about a dramatic break with ‘Old Bolshevism’. On the basis of my original research into Russian and Latvian Bolshevik newspapers, leaflets, minutes, and resolutions across the empire in March 1917, I will show below that irrefutable primary sources undermine the entire edifice of Trotsky’s argument.

The top Bolshevik leaders in March––including both Kamenev and Stalin––did call for the elimination of the Provisional Government and the establishment of a revolutionary soviet government. Only by breaking with the national and imperialist bourgeoisie, they argued, could working people end the war, win their social demands in Russia, and spark the world socialist revolution. Without this programmatic foundation, the rise of the Bolshevik party in 1917 would have been unthinkable. April marked a moment of political evolution rather than strategic rupture for Bolshevism.

My argument coincides in part with historian Lars Lih’s groundbreaking challenges to Trotsky’s narrative.[5] The available evidence generally corroborates Lih’s stress on the Bolshevik party’s radicalism in March and its strategic continuities up through October 1917. That said, Lih overstates the case by minimising the early political vacillations of the party and downplaying some significant changes in Bolshevik politics over the course of the year.

Despite the party’s militant strategy, Bolshevik leaders not infrequently politically bent to moderate socialists and workers during March, particularly in the periphery of the empire. In most regions, this wavering constituted a break from (rather than expression of) the stance articulated by the party’s ‘Old Bolshevik’ leadership. But political inconsistency before Lenin’s return was also facilitated by certain tensions in Bolshevik strategy, particularly its open-ended approach to which party and class should lead the revolutionary regime. Ambiguities in the ‘Old Bolshevik’ call for a ‘democratic dictatorship of workers and peasants’ meant that party policy could be–and indeed was–developed in distinct directions following Tsarism’s demise.

On the whole, however, it is justified to highlight Bolshevism’s continuities in 1917, especially because these have been so widely denied by decades of historiography. Bolshevik vacillations–unavoidable to a certain extent for any political current engaged in mass struggle–were overshadowed by the current’s general orientation to proletarian hegemony.

Trotsky can be excused for putting forward a one-sided account of ‘Old Bolshevism’ during his desperate struggle to uphold workers’ democracy and proletarian internationalism against rising Stalinism in the 1920s. In the face of an increasingly bureaucratised Communist party and Soviet state, it is hard to fault Trotsky for using all the polemical weapons at his disposal to discredit the ‘Old Bolshevik’ triumvirate of Stalin, Kamenev, and Grigory Zinoviev. But there is no need today to remain wedded to Trotsky’s interpretation of early 1917, which is clearly contradicted by a wide range of primary sources. Revolutionary Marxism, including the strategy of permanent revolution, is strong enough to withstand a critical re-assessment of the actual politics of Bolshevism in March 1917.

The Political Context

Bolshevik policy prior to Lenin’s arrival in Petrograd can only be adequately examined in light of the context of that very particular moment in the revolution. At no other point in 1917 would the stance of both the Provisional Government and the moderate socialists be so in line with popular sentiment.

By March the basic structure of dual power had been established in the capital and across the empire. The Provisional Government nominally ruled the land, but the soviets held more real power and authority. Elected by nobody, and isolated from the working class due to the liberal leaders’ longstanding support for the war and the monarchy, the Provisional Government’s survival depended on the support given to it by the moderate socialist leaderships. In the eyes of most politically active workers and soldiers, the soviets were the sole legitimate power. In the famous phrase of the 2 March Petrograd Soviet resolution, the new bourgeois administration would be supported only ‘in so far as’ [постольку, поскольку] it met the people’s demands.

Menshevik leaders could largely take political credit for establishing this dual power regime, which to a great extent reflected their post-1905 strategy of conditional support for the liberals. Though Menshevism remained a heterogeneous political tent, one fundamental point upon which all wings agreed was that the bourgeoisie must assume the reigns of power following the downfall of the autocracy. Given Russia’s backward social conditions, socialist transformation was impossible and, therefore, a working people’s government was off the table.

By 1917 most Mensheviks had long ago abandoned the strategy of the hegemony of the proletariat and viewed liberals as indispensable allies of the proletariat. On an immediate level, they felt that only an alliance with a wing of the bourgeoisie would be sufficient to defeat the serious threat of a right-wing counter-revolution. Ideologically, the Mensheviks were committed to the view that decisive forces in the upper class would support democracy and social progress against the remnants of feudalism. At the same time, opinions among Mensheviks continued to vary widely concerning expectations in Russian liberalism. This is important to stress, since Menshevism in March was significantly more oppositional than it became after the April Crisis and the conciliatory socialists’ subsequent entry into the Provisional Government.

In early 1917 the general Menshevik sentiment was that steady pressure by an independent labour movement was necessary to push from below to overcome the hesitations of the bourgeoisie. Mensheviks held firm to this relatively oppositional stance for most of March and they sought to use their strength to steer the government in a progressive direction. Thus they rejected the liberals’ initial attempt to maintain monarchic rule; they asserted the Soviet’s political control over the mass of soldiers; they sought to build up the Soviet as an effective proletarian bastion to drive forward the government and society generally; and they initiated a major campaign to pressure the Provisional Government and the Allies to take concrete steps towards ending the war.

Under the leadership of the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs), the Soviet scored some important early victories. It obliged the Provisional Government to grant political freedom and legal equality for all, abolish the police and security apparatus, release all political prisoners, refrain from reprisals against mutinous soldiers, remove the top Tsarist officials, and agree to rapidly convoke a Constituent Assembly. The latter promise, in particular, should be underscored, since many socialists in March emphasised the provisional nature of the current government, which they believed would only be around for a few months.

The viability of the Menshevik dual power plan hinged on two factors: the bourgeoisie’s ability to continue to meet the people’s urgent demands and the proletariat’s ability to refrain from pushing too far, too fast. Events would soon show that neither class behaved in the way the Mensheviks had hoped.

March constituted the high point of the Provisional Government’s grudging acceptance of progressive measures. Despite the Soviet’s campaign for peace, Russian liberals––backed by French and English imperialism––continued the war and stated that no major social reforms would be implemented until military victory. When news of the administration’s plans to continue the war ‘until victory’ became public in April, anti-government demonstrations and riots broke out in the capital, against the wishes of the Soviet leadership. The April Crisis made it clear that the current Provisional Government lacked sufficient popular legitimacy to govern. A restructuring of the administration––and Menshevik strategy––was required. Forced to choose between their principled opposition to participation in a capitalist government and their commitment to an alliance with liberals, the Mensheviks chose the latter.

Bolshevism and Revolutionary Government

The specific political configuration of Russian society in March 1917 had not been foreseen by the Bolsheviks. From 1905 onwards, they had assumed that either workers and peasants would establish their own ‘democratic dictatorship’ or Russian liberals would come to power in the framework of a constitutional monarchy. Yet the unexpected emergence of a post-Tsarist liberal government did not invalidate the Bolsheviks’ main line of march: proletarian hegemony to establish a revolutionary workers’ and peasants’ government to end the war and meet the people’s urgent social demands. ‘Bolshevism did not primarily make a prediction about the day after the fall of the tsar, but rather proposed a scenario of the “active forces” of Russian society, joined to a corresponding strategy for carrying the revolution “to the end,”’ notes Lih.[6]

In the first few days of March, the most radical (arguably ultra-left) Petrograd Bolsheviks had called for immediate mass agitation for an armed uprising against the Provisional Government.[7] Most Bolshevik leaders, in contrast, argued that such a push was dangerously premature, given that workers generally supported the moderate socialists in the Soviet; since the Bolsheviks were organisationally weak; and because revolutionary developments outside Petrograd lagged behind the capital.[8] Additionally, the Provisional Government in these very days was ceding to key democratic measures. As Bolshevik leader Filipp Goloschekin put it at the party’s late March conference, ‘the Provisional Government is counter-revolutionary both in its personnel and in its essence. Under the pressure of the masses it is accomplishing revolutionary tasks, and to this extent, it entrenches itself. We must not overlook that the masses are saying that the Provisional Government has done everything. … If we want to struggle against the counter revolution, we must aim for the seizure of power, but without forcing events.’[9]

On 4 March, the Russian Bureau of the Central Committee––the top Bolshevik leadership body inside of Russia, led by Alexander Shlyapnikov and Vyacheslav Molotov––affirmed the current’s strategic orientation in a resolution published in the party’s central newspaper, Pravda:

The present Provisional Government is essentially counter revolutionary, because it consists of representatives of the big bourgeoisie and the nobility, and thus there can be no agreement with it. The task of the revolutionary democracy is the creation of a Provisional Revolutionary Government that is democratic in nature (the dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry).[10]

The Vyborg Bolsheviks felt that this goal was an immediate task and passed the following resolution at a big factory rally in early March: ‘The Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies must immediately eliminate the Provisional Government of the liberal bourgeoisie and declare itself to be the Provisional Revolutionary Government.’[11]

Other Bolshevik leaders put forward a somewhat more cautious tactic. On 3 March the Petersburg Committee of the party resolved that it would ‘not oppose the Provisional Government power in so far as its actions comply to the best interests of the proletariat and the broad masses of the democracy and the people.’[12] Various authors have incorrectly claimed that these Bolsheviks had thereby adopted the Mensheviks’ stance of conditional support for the Provisional Government.[13] In fact, the resolution only implied that the Bolsheviks did not seek to immediately eliminate the regime and that they would support the specific progressive measures that it implemented––additionally, as Bolshevik leader V. N. Zalezhsky explained, the use of the phrase ‘does not oppose’ instead of ‘support’ was consciously employed to differentiate the Bolsheviks’ stance from that of the Soviet leadership.[14]

The political orientation of the Bolsheviks’ Petersburg Committee was soon expounded in the party press. One of the more articulate explanations came from Latvian Bolshevik leader, Pēteris Stučka, a member of the Petersburg Committee and one of the three Bolsheviks represented in the Soviet Executive Committee. As a supporter of the Petersburg Committee’s 3 March ‘in so far as’ resolution, Stučka elaborated on how it fit into party strategy in his 7 March article ‘Our Mission’.

This important document––overlooked in the historiography because it was published in Latvian––sought to answer ‘whether the revolution has come to an end or is just beginning’ and, subsequently, how the Bolsheviks addressed the question of state power. Stučka noted that though the workers and peasants in uniform had made the revolution, the Provisional Government was run by the ‘counter-revolutionary’ bourgeoisie. The new administration had been obliged by popular pressure to take some real steps forward (such as eliminating the monarchy), but it was incapable of meeting the essential tasks of the revolution: ‘As soon as it loses the support of the revolutionary people, it will fall.’ He explained that this strategic perspective constituted ‘the foundation which separates us from the moderate leftists’ who believe that ‘the fall of the Provisional Government would mean the collapse of the whole revolution’.

In contrast, Stučka concluded that only a ‘truly revolutionary provisional government, that is, a provisional government of workers and peasants’ could lead Russia out of its crisis and meet the demands of the people such as land to the peasants and an end to the imperialist war. With this state power objective in mind, the immediate task of revolutionaries was to reject ‘moderation’, to raise ‘direct revolutionary slogans’, and to ‘criticise every step’ of the Provisional Government, while ‘supporting only those [steps]’ that did not go against the development of the revolution.[15]

Clearly Bolshevik leaders integrated the ‘in so far as’ formulation into a distinct strategy from that of the conciliatory socialists. Petrograd Soviet leader Nikolai Sukhanov recalled that to not oppose the Provisional Government’s progressive steps ‘was the official position of the Bolsheviks at that time. But the sabotaging of Right Socialists, and demagogy addressed to the masses—that was also their official position.’[16] Whereas the Menshevik leadership actively supported the establishment of bourgeois rule and limited its strategic perspective to pressuring the liberals, the Bolsheviks rejected an alliance with the bourgeoisie and explicitly called for the replacement of the current government with a workers’ and peasants’ regime. Russian historian V.I. Startsev notes that ‘the similarity of the [3 March Bolshevik] resolution to the 2 March Soviet resolution was purely superficial, one could say grammatical, in that it included “in so far as”’.[17]

‘Old Bolsheviks’ in March were quite clear that the revolution was far from over. Crucially, the Bolsheviks never reduced the goal of the democratic revolution to ending autocratic rule––in their view, this upheaval would only be complete once the landed estates were confiscated, the workers armed, a republic established, and a series of radical economic measures enacted. As ‘Old Bolshevik’ Nikolai Miliutin put it later in the month, ‘our revolution is not only a political but also a social revolution.’[18]

On 12 March, party leaders Kamenev, Stalin, and Matvei Muranov arrived in Petrograd and promptly assumed editorial responsibility for Pravda. Their arrival tilted the balance of forces towards the relatively cautious elements within the party leadership and away from the more intransigent Russian Bureau and Vyborg Committee. Put simply, Kamenev and Stalin promoted the revolutionary ‘in so far as’ line first elaborated by the Bolshevik Petersburg Committee on 3 March.

Contrary to Trotsky’s unfounded claims, the new Pravda editors openly affirmed the party’s objective of eliminating the current government and putting all power into the hands of workers and peasants.[19] Throughout the month, Kamenev and Stalin affirmed that they did not support the government as such, only the particular progressive actions that it was compelled from below to implement. To quote Kamenev: ‘Support is absolutely inacceptable. It is impermissible to have any expression of support, even to hint at it. We can not support the Government because it is an imperialist government.’[20]

In a 14 March article, Kamenev clearly reiterated the standard Bolshevik perspective on state power:

The proletariat and the peasantry and the army composed of [these groups] will consider that the revolution that has begun will be completed only when their demands are entirely and fully satisfied, when all the remnants of the former regime are torn to the ground, both in economic and in the political sphere. This full satisfaction of the [demands of] workers, peasants and the army is possible only when all the power is in their own hands. Insofar as the revolution will widen and deepen, it will arrive at this, to the dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry.[21]

To underscore the continuity of their strategy on soviet power, on 17 March the new editors published on Pravda’s front page the entire Bolshevik 1906 resolution on the soviets, which affirmed that these bodies were ‘embryos of revolutionary power’ that must be ‘turn[ed] into a provisional revolutionary government’ through a proletarian-led uprising. The editors declared that the orientation of the resolution ‘basically remains true today’ even though ‘today’s soviets operate on a terrain that has already been cleared of Tsarism’.[22]

This line was developed in Pravda’s 18 March issue, in which Stalin explicitly called for the establishment of an empirewide Soviet body, which must take political power. ‘The first condition for the victory of the Russian revolution’, he argued, is that an ‘all-Russian Soviet’ must ‘transform itself at the necessary moment from an organ of the revolutionary struggle of the people into an organ of revolutionary power’.[23]

To be sure, Kamenev and Stalin (unlike the most radical elements in the Bolshevik party) were not calling for the immediate overthrow of the Provisional Government. Against the impetuousness of Petrograd Bolshevik militants eager to initiate an armed uprising at the earliest possible moment, Kamenev insisted that it was necessary not only to conquer power, but to keep it.[24] ‘This moment will come, but it is beneficial for us to delay, as our forces are still currently insufficient’, he argued in the Petrograd Committee.[25]

The Pravda editors in March viewed party isolation and tendencies towards ultra-leftism as a grave danger. This issue was not a figment of their imagination: wings of the Petrograd organisation, particularly in the Vyborg district, were treading close to Blanquism by pushing to take down the government well before the majority of workers supported soviet power. After returning to Russia, Lenin similarly fought hard against impatient Bolsheviks, whose reckless actions in April and July threatened to abort the revolutionary process through a premature uprising.

Similarly, there is considerable evidence that Pravda’s flanking tactics may have been the best suited for the political climate in March. To cite just one example, Israel Getzler’s study of Kronstadt shows that the tactical pivot under Kamenev’s guidance succeeded in turning around the party’s fortunes in this strategic locale: ‘If the unsuccessful Bolshevik debut in Kronstadt [under the influence of the Vyborg Committee] was to some extent due to its aggressive, ‘maximalist’, jarring tone, the moderate, ‘minimalist’ stance adopted from the latter part of March until the ‘April Days’ seems to have served well in the building up of the Bolshevik party organization and influence.’[26]

Calls in March for a revolutionary soviet government (and/or dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry) were not limited to Petrograd. In Latvia, one party committee declared that ‘the only consistent expression of the workers’ interests is the Soviet of Workers' Deputies, and therefore it is our duty to support it in every way, to transfer the power of the Provisional Government to it, and through this to continue the revolution until final victory.’[27] Similar proclamations were made by Bolsheviks in Moscow, Ekaterinburg, Kharkov, and Krasnoyarsk.[28]

The April 3-4 Bolshevik Moscow citywide conference likewise gives a good sense of the general party leadership’s state perspective on the eve of Lenin’s return. Only a single person, V.I. Yahontov, opposed the fight for a new revolutionary regime, arguing that ‘if the working class takes power into its own hands, it will not be able to cope with the economic breakdown.’ The other delegates responded by shouting him down––‘you are a Bolshevik?’ they taunted.[29] Yahontov immediately after joined the Mensheviks, as did a handful of co-thinkers in Petrograd led by Wladimir Woytinsky (who was likewise sharply criticised and politically isolated by the Petrograd Bolsheviks).

It is significant that the very few opponents of seizing power among the Bolsheviks were overwhelmingly marginalised before Lenin’s return and that they therefore immediately joined the Menshevik party. If there were no major differences between the currents, as Trotsky implies, how can one explain the resignations of Yahontov and Woytinsky?

Likewise, how are we to account for the numerous examples of the right-wing press publicly singling-out the Bolsheviks for political denunciation? Shlyapnikov’s memoir documents ‘the furious persecution and slander’ of the upper class against the party throughout the month due to its opposition to the war and the government––‘the hostility of the bourgeoisie proved to us that the decisions we took were correct’, he concludes.[30] Michael Hickey’s recent work on the revolution in Smolensk similarly observes that ‘Bolshevist positions repeatedly came under fire in the local press even before Lenin's return to Russia’.[31]

Bolshevism’s stance on the war and the Provisional Government was also sharply attacked by the moderate socialists in March. The party’s refusal to support the military effort was particularly controversial. As Shlyapnikov recalls, ‘the bourgeoisie and the defencist Mensheviks and SRs managed to create literally a pogrom mood against us. There were days when we could not speak to soldiers to outline our internationalist views.’[32] Polemics over the question of soviet power likewise began well before Lenin’s return. Against their radical rivals, the Mensheviks responded that the need for an alliance with the bourgeoisie, as well as the low level of Russia’s level of economic development, precluded the rule of working people. ‘If the Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers’ Deputies took power into its own hands, it would be an illusory power, a power that would immediately lead to the eruption of civil war,’ declared the Mensheviks’ main Petrograd newspaper.[33]

As we have seen, Bolshevik leaders explicitly called for a soviet regime prior to the arrival of Lenin in April. Contrary to the assumptions of most academic and activist historians today, socialist revolution was not seen by Marxists at this time as a necessary corollary of soviet power. Looking back at the politics of the party in March, Stučka noted in 1918 that ‘we, the Bolsheviks, the Petrograd executive committee, both raised the demand for all power to the soviets, but we did not yet think about immediately moving to socialism’.[34]

It should be underscored that until late 1917 the demand for ‘All Power to the Soviets!’ concretely meant the establishment of a government led by the Mensheviks and SRs, two currents openly opposed to direct socialist transformation. Similarly worth noting is the fact that the Menshevik Internationalists later in the year called for a soviet government but not socialist transformation. Thus Rafael Abramovitch, a central leader of the Menshevik (and Bundist) Internationalists, argued in July 1917 that the Soviet must take the reigns of power.[35] He declared: ‘The revolution now only has one way forward: the dictatorship, the rule of the working class, together with the revolutionary layers of the urban and rural petty bourgeoisie! In Russia, the bourgeois-democratic revolution must take place without the help of and even against the will of the middle or big bourgeoisie!’[36] Various other parties and currents across the empire put forward calls for soviet power from a range of distinct strategic perspectives, most of which did not include socialist revolution.[37]

Unlike the later-day stageism of the Stalinised Communist International, the ‘Old Bolsheviks’ did not argue that socialist transformation in Russia could only take place after an extended period of capitalist development and political democracy. In fact, Bolshevik leaders explicitly rejected this view in March 1917. They argued, instead, that the working class at the head of the peasantry had to seize power in Russia to spark the international overthrow of capitalism.

In countless leaflets, speeches, and articles, Bolsheviks affirmed that the capitalist crises expressed and exacerbated by the imperialist conflict must lead to an imminent world socialist revolution, which would allow the Russian Revolution to move beyond capitalism. In a typical article on 21 March, Stučka made the case for why revolutionary Marxists in the Russian empire rejected the view that ‘first there must be a long period of social freedom and only then can one start a serious struggle for socialism’, which would mean ‘postpon[ing] socialism itself for many years’. He explained that while ‘there was little hope of putting socialism into practice within Russia’s borders only, the rise of social revolution across Europe without a doubt will also drag Russia into it.’ The transformative experience of revolution, Stučka declared, would allow Russia’s workers to reach radical conclusions without an extended period of political freedom: ‘it should be noted that six months in the life of a revolution equals the same as decades of peaceful development.’[38]

Up through and often well past October, most Bolshevik leaders continued to predicate the potential for any substantial socialist transformation of the Russian economy on successful proletarian revolutions in Europe. Lenin’s April proposals for ‘steps towards socialism’—calls for ‘socialist revolution’ in Russia were conspicuously absent—did not include expropriating capitalist industry. He posited that ‘we cannot be for “introducing” socialism—this would be the height of absurdity’ since ‘the majority of the population in Russia are peasants, small farmers who can have no idea of socialism’.[39] Explicitly disputing the claim that he was aiming to ‘skip’ the bourgeois-democratic stage, Lenin insisted in April that he was not advocating a ‘workers’ government’ but rather a broader regime of workers, peasants, soldiers, and agricultural labourers.[40]

For months after the October Revolution, Lenin and the Bolshevik leadership continued to push back against the calls and initiatives from below to nationalise production. Nevertheless, as Trotsky had predicted in 1906, upon leading workers to power the Bolsheviks were compelled to go much further than they had initially planned. Capitalist economic sabotage, workers’ wildcat expropriations, and the dynamics of civil war swept the party into nationalising all major industries in the second half of 1918. Though there was likely no other viable option in the given circumstances, this wave of premature nationalisations deepened the catastrophic collapse of production and played a central role in the massive growth of a privileged state bureaucracy.[41]

Bolshevism’s evolution regarding socialist transformation was far more convoluted and protracted than has usually been assumed. Though the historical record undermines claims that Lenin won the party to socialist revolution in April 1917, it confirms the prescience of Trotsky’s argument for permanent revolution made eleven years prior:

Under whatever political banner the proletariat has come to power, it will be obliged to take the path of socialist policy. It would be the greatest utopianism to think that the proletariat, having been raised to political domination by the internal mechanism of a bourgeois revolution, will be able, even if it so desires, to limit its mission to the creation of republican-democratic conditions for the social domination of the bourgeoisie.[42]

Conciliation in the Capital