On Understanding Our Needy World through SF and Utopia/nism

An Epistemological Introduction

By Darko Suvin

Why did the heathens tremble and the peoples imagine inanities?

- Psalm 2

The catastrophe is that things just go on as before.

- Walter Benjamin, Central Park

When no hope is left, one has to follow one’s principles.

- Old miner in Brassed Off (dir. Mark Herman, 1996)

0. Categories

For a forthcoming book of mine dealing with science fiction (SF) and utopia/nism, I opted for an approach that I call political epistemology. It attempts to fuse a reflection on how we understand what we think we understand (which in humanities or arts one calls texts, whether musical, pictorial or verbal…) with an emancipatory political stance that leads to focussing on contradictions and splits in meaning and the body politic.

Looking at the essay-chapters of that book of mine (still seeking a publisher), Disputing the Deluge, I wondered what makes them part of the same argument, that is, how do the various parts and levels of a longer text feed back into and reinforce one other? Inevitably, through categories illuminating and, one hopes, largely justifying the whole. (Once and for all, I do not mean that categories must be explicitly presented as a system anywhere in such a text, though many texts that owe allegiance to scholarship or systematised knowledge may do so.) Categories are, up to a point and perhaps obliquely, always present in a text. But their being teased out and understood by a reader also ought to illuminate the main nodes of the text, making it richer and clearer. These nodes are mostly, as Jameson put it, ‘formal peculiarities of … narratives’,1 with all the rich thickness of artistic cognition, which then may, in a preface or conclusion (or indeed a loyal review), be thinned down to the ideational or notional skeleton indispensable for an overview. How does one pick the categories needed for understanding? They must not be too many – to my mind, using more than circa five main categories confuses the memory of reader and writer alike – and it would be economical if they reinforced one other. The rest is situational wisdom, what the Germans call Fingerspitzengefühl, an intuitive flair for the situation in the text (on the author’s side) and of the book (on the reader’s side).

I shall, here, concentrate on a few categories needed for understanding or cognition, which, in my case – since I explicitly claim that the ideal horizon and cases of SF and utopia/nism are cognitive – means that I wish to understand cognition or cognise understanding. I trust this can be done without falling into a vicious epistemic circle. However, it needs to remain an abbreviated overview for who’s fleshing out, I must regretfully often refer to other works of mine (based upon insights by many other people).

1. Knowledge, frames, structures of Feeling

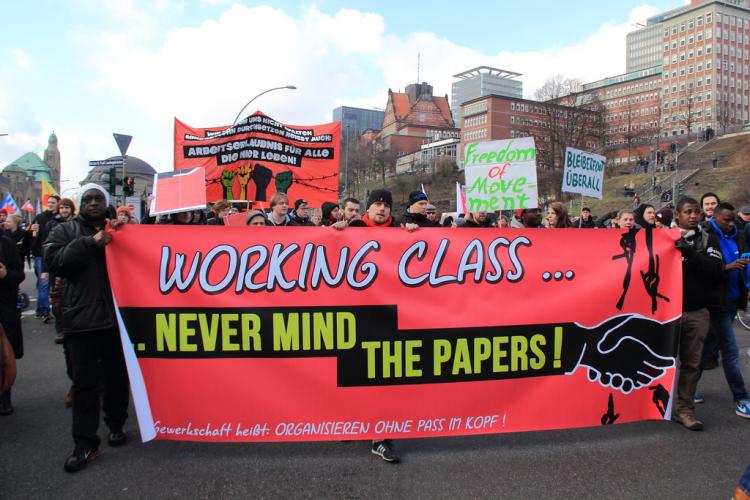

1.1 What do I understand by ‘knowledge’ or ‘understanding’? And what is the function of us intellectuals as their bearers? Let us start from our dire class situation, where most of us live by our work, that is to say are objectively a part of the working people against whom a more and more stringent class war from above is being waged by our rulers, capitalists and their henchmen. Today, we live in a perverted ‘knowledge society’ where brainwashing images and words have polluted the very structure of our perception and experiencing. Useful knowledge and perniciously fake knowledge are closely intertwined, and any realistic understanding must include a detoxification and deprogramming of hegemonic understandings. Knowledge as use-value for living is being evicted by knowledge as exchange-value for profits, with its logical end in ‘smart bombs’ for mass killings, or ‘smart’ online work that may serve as a stopgap but finally increases alienation as against sociability. This is why I cannot see how a civil life can survive without first establishing a great deal about how we know what we believe we know. In other words, there is no way around focusing on some knots within our understanding, formalised as a political epistemology.

I adopt the definition of epistemology as the theory of human knowledge, preoccupied with the latter’s possibilities and limits, with the analysis of propositional and metaphoric (and thus logical and affective) cognitive systems, and in particular with the critique of language and other sign systems as concrete consciousness.2 Epistemology speaks to ‘how do we know what we (think we) know’ not in terms of individualist psychology but of the collective conditions that make knowledge possible. It stages, on a theoretical level, an encounter of knowledge, art, science, and liberatory politics which started out together in practice, and, at its best, mediates between theory and a return to practice: who, and in whose interests, decides the meaning of terms and what they enable or disable?

Now, any epistemic tool defines its object-types and its subject-wielders as something and to (for) something: it allows an access to the world of signifying and finally of significant potential actions. We must realise, as both Lenin and feminists did, that epistemology does not function without our asking the political question ‘In whose interest?’. Interests and values decisively shape all perception: it was Marx's great insight that no theory or method can be understood without the practice of social groups to which it corresponds. Thus, our answers can be found only in a feedback loop with potential action. As Vico argued, whatever we cannot intervene into, we cannot understand; it follows thatthe epistemological and the political intertwine.

To advance in this lush jungle of opinions and prejudices, I need to begin with two foci: on categories and on structures of feeling. Categories first.

1.2 I see categories as frames. Understanding and action proceed by means of groupings into kinds of things: a pine is a tree, a plant, and so on. All seeing is seeing-as (Wittgenstein), in categories. The always-already existing frames are cultural mega-presuppositions, latent in all the resulting positions. How am I going to see or understandX without them? As a rule, there is a set of concentrically embedded frames that determine thisX. My operative frame is SF and/or the horizon of formulatingutopia. A given story is inside such a framing. Outside of it, it is not readable. You can register, but not read with understanding, an opening line likeThey landed in the light of the blue sun if you don’t know the presuppositions it carries. This line, if you’ve never read SF, makes no sense. But what does it mean when framed? Easy: we are in another solar system, and not in ours where the sun is yellow; and the inhabitants of the planet can be anything the author pleases, except that they are always analogies of our hopes and fears, utopian or anti-utopian. The opening feeds into what the theoreticians call a reading protocol for this kind of story. How do you understand it? By reading a lot of this stuff with interest! If you are a fan, you won’t wonder. But if you’re not? After five sentences like this, you’ll get lost because you don’t know which category – to begin with, which literary genre – you are in. Surrealist or nonsense poem, weird disturbance of sight, an experiment by malevolent Lovecraftian gods?

However, this operative frame can only come into being because it grows out of a matryoshka-style embedding into wider frames. The widest one, for our purposes, would be ‘human collective understanding/s of common reality’ and a middle one ‘imaginative literature’ or ‘fiction’. The widest one can be briefly summarised, freely following Lakoff and the Eleanor Rosch school, as ‘Thought is embodied, imaginative, and a gestalt’. First, human understanding begins with perception, bodily movement, and situated physical and social experience. Second, ‘those concepts which are not directly grounded in experience employ metaphor, metonymy, and mental imagery’. Third, the concepts (I would prefer to call thempropositions) are not atomistic but have an overall structure in dynamic feedback between particular and general imaginative structures. This view of understanding implies an axiomatic commitment to the existence of a common world, which necessarily places constraints on human imagination, as well as to the existence of a shared though constantly changing knowledge of that world.3 As Putnam provocatively put it, meaning is not in the mind – but in mind’s interaction with world.4

Thus, categories are our indispensable cognitive tool. Of course, when seeing X, different people will not only see it in slightly different ways and use slightly different categories to understand the seen, but there can be outright illusions, frauds, and mass hysterias (example: UFO sightings in USA; or today, Trumpism and other forms of fascism 2.0 as bearers of mass salvation). Furthermore, some categories are graded and with fuzzy boundaries (example: a tall person) and others may have clear boundaries (example: bird) but also a graded spread, so that some members are better or worse examples of the category.5 But this model of seeing is linguistically unavoidable, in good part automatic and unconscious, and ideologically fortified as the norm.6 True, categorising can be, like almost everything, abused for purposes of pedantry and/or dogmatism. However, it is potentially a deeply philosophical cognitive pursuit: it determines the Possible World of a text.

1.3 Yet one more tool is needed to explain deep ideological and epistemological oppositions between large human groups when it comes to categorising: class interests and their divergence. A crass example is under all our eyes: in a pandemic such as the current Covid-19 one, a very large majority of people wants their superordinated community (here the state) to take as an absolute priority their survival; a small minority, as a rule, less than 5%, takes as an absolute priority their profits – and using national chauvinism and other demagogic illusions, they can enlist maybe 30% of people to follow them, as Hitler and Trump did. The reigningdoxa or common sense can be built up into huge and apparently seamless systems of fake categories, of which the most important in late capitalism is the social Darwinism coursing from Rockefeller Sr. to Trump.7 A wonderful example is the brief 1984 kerfuffle in the US press that Lakoff reports,8 based on the report by Robert Half Inc. – described in Google as the world’s biggest accounting firm, with a revenue of 6 billion US$ in 2019 – that US office employees steal on average 4 hours 22 minutes per week from their employers by malingering. When you compare this with Marx’s labour theory of value, by which almostall profits from capital originally come from appropriating a major part of the workers’ labour-power (that is, unpaid working hours in comparison to what they actually produce), the divergent class interests become quite clear. The categories collide.

The richest way to understand them is to use Williams’s ‘structures of feeling’ or structures of experience, as I have often attempted in my work.9 According to this theory, all artistic works – and more fuzzily, one could infer, all our systems of understanding – embody an overriding epistemological framework that rests on a ‘structure of feeling’ or of experience, differentiated by period, generation, and in cases of acute social tension by class groupings, making for hegemonic, nostalgic, and oppositional horizons as well as for different ‘semantic figures’, that is, forms and conventions.10

2. On the collective understanding of shaping words

Let me, therefore, advance from the outermost frame of any collective understandings of common reality as just argued – always bearing in mind there can be competing collectives – and restrict political epistemology here to the already daunting domain of understanding or cognition in words (language).If Disputing the Deluge, in seeking out what we need for collective and personal salvation, arrived finally at the need of a fusion between an organised plebeian political upsurge and depth utopian energies, it would seem useful to propose here some initial, necessarily laconic theses ona method for radical utopian cognition. They are an amendable initial view and stance. They re-produce – that is, both repeat and advance from – some of my writings of the last quarter century.

It follows from my brief discussion of Williams that cognition is not only open-ended but also codetermined by the social subject and societal interests looking for it: its horizons are multiple. Not only is this legitimate, it is unavoidable and all-pervasive. The object of any praxis can only be ‘seen as’ that particular kind of object from a subject-driven standpoint and bearing that is personal but also collective. If you want to be Master of your Company, you have to treat profit-making concepts as raw material on the same footing as profit-making labourers and iron ore. Bourgeois civilisation’s main way of coping with the unknown is aberrant, Nietzsche once argued, because it transmutes nature into concepts with the aim of mastering it: that is, it turns nature only into concepts and furthermore makes a more or less closed system out of those concepts. It is not that the means get out of hand but that the mastery – the wrong end – requires appositely wrong means. The problem lies not in the Sorcerer’s Apprentice but in the Master Wizard.

2.1.Premise

In both our presuppositions and our positions, a double cognitive movement is necessary: destruction (deconstruction) of old ways of thinking, focussing on useless interpretation of key terms; construction of dialectically flexible, usable meanings for such terms, having a constant denotative core along with a pulsating (expanding and shrinking) periphery of connotations. The rhythm and direction of the pulsations is historically contingent and situational, it too is subject to phronesis (practical wisdom) rather thantheoria.

Our tools as essayists are, no doubt, notional; they are regulative ideas. However, I shall argue in 2.2 below that, in all richer cases, they rest on ametaphor (in the widest sense of a trope). They are all initially located in the imagination, but ‘imagination becomes reality when it enters the belief of masses’ (Marx, slightly tweaked).

All understanding carries its own delight, of a piece with its end to make life easier and more pleasant. Cognition – artistic, scientific or any other – is a joy and pleasure, it fuses logic and emotions. It is always an imaginative synergy between Pascal’s ésprit géometrique, the intuitive ésprit de finesse, and last not least (in what today seems a somewhat archaic metaphor), the ésprit du coeur or emotional wisdom. If emotions are tools for understanding the world,11 they can be right or wrong, clear or muddied, just like any propositional or notional system: another highly important but usable and misusable tool or faculty.

A first axiom: the survival of Homo sapiens sapiens has precedence over the profit principle.

2.2. Cognitive acts in words

First, cognitive acts in words (often called ‘discourse’ in French theory) are not closed or walled off – simply a combination of discrete linguistic units – but rely on an interplay of identification (what is presented as being in singular: Peter, this table, the fall of Rome) andpredication (a quality, a class of things or a type of relation) in any sentence or proposition: who or what relates how toX. Was the fall of Rome to supposed barbarians, which we take to have ended the slave-owning system, a terrible crash or a refreshing renewal, a palingenesis? For whom was it either or both?

Second, when dealing with sentences, Frege’s Sinn und Bedeutung12 are best translated as sense and meaning, avoiding the huge minefield of competing uses of “reference”: sense operates through relationships within the sentence language correlating the identification function and the predicative function, while meaning refers to the Possible World of the text, where ‘language is directed beyond itself’.13A text’s propositions and metaphors always arise ingiven situations, and Sartre would add within our freedom to understand situations,14within an imagined community; in all poetry or narration they imply, shape, and in turn presuppose a Possible World on the analogy of what we imagine is ‘our world’, and only within it do they have a meaning

Third, cognitive acts in words are sometimes seen as divided into two distinct sub-ensembles: propositional and metaphoric. But this seems to me outdated semantics, based on linguistics à la Benveniste, for meaning encompasses very much also all connotations, implications, affects, echoes, and analogies of the so-called propositional content. There isno ‘said as such’15 – unless, perhaps, for specific narrow purposes, as in much specialised philosophy. Conversely, every true metaphor is a dialectical contradiction: in each metaphor kinship appears where ordinary vision or ruling common sense sees none, in what stricter philosophers like to dub a ‘category mistake’.16 This ought to induce us to use categories prudently.

Between the beginning and the end of any unit of cognition-in-words the reader may understand something, in the best cases a novum – a new event or existent – by induction from experience. His take on the world in which he acts or is being acted upon is modified by the experience of other possibilities, of Possible Worlds.

A second axiom: human nature abhors meaninglessness.

2.3. On dialectical totalities

Pre-industrial totality was ideally stable; it could accommodate slight or at any rate non-structural, changes in the fashion of Tomasi di Lampedusa’s slogan in TheLeopard (Il Gattopardo): ‘everything changes [in politics] in order to remain the same [in economics]’. Such totality was then perverted by Gentile and Mussolini into the ideology of ‘totalitarianism’, meaning total organisation of society by the state from above, fusing the politics and economics; Nazism brought this to perfection, while Stalinism largely came to follow a kindred idea, equally bloody if more productive in technologically backward societies. Both were centrally aspiring to a kind of divine perfection, perhaps relevant to times before the Industrial revolution and its new normality of disconcerting change within one lifetime, beginning with the Napoleonic wars: not to speak about the following revolutions in technology and cognition, in perfectly evil feedback with bigger wars. Shocked by all these politics, Arendt and the liberaldoxa of postmodernism not only rightly refused them but also threw the baby out with the bathwater, logically ending in ‘weak thought’ (pensiero debole).

It is much more economical to wash and grow the baby: that is, to retain the concept of strategic, flexible, and imperfect totalities.17 ‘Strategic’ means shaped by deep and cognitively argued macro-situational necessities; ‘flexible’ means changeable in extension and intension; ‘imperfect’ means not only unfinished but, in principle, unfinishable dualities and multiplicities. No image or notion is graspable except as such a (provisional!) historical totality. Thomas More’s great insight, philosophical and literary, was to formalise such a totality in his Book 2 of Utopia as a happy and virtuous country and counter-universe organised in politico-economical categories, not simply a moral fable about a piecemeal problem as were his Polylerites, Achorii, and Macarenses in Book 1,18 estranged into abstract generality rather than into sociopolitical analytics.

‘Total’, in this discussion, does not mean all-exhaustive, nor that everything is to be planned from above and violently enforced, as Cold War propaganda insinuated. Many major SF and utopian writings are open-ended totalities. Indeed, every poem, story or book is an invitation to the readers’ cognitive participation and re-membering. Any totality has inbuilt contradictions which make for changes, glacially slow or explosively sudden. The art of planning, of being ready for the unforeseeable future, is to find the dominant contradiction.19

A third axiom: strategic, flexible, and imperfect totalities are the only thinkable cognitive acts.

3. Some transitive foci of utopia/nism: around anti-utopia

From a number of categories under which the cognitive investigations of SF and utopia/nism can be grouped, I can here dwell only on freedom vs. destiny, some further aspects of anti-utopia, and our salvational choice: violence vs. care. The first of these three foci leads into some further delving into anti-utopia and the third follows logically as its upshot.

3.1. Freedom and destiny: the arbiter actant

As Marx clarifies in Capital,Volume 3, in the sphere of material production – which is under the sway of necessity – ‘[freedom] can consist only in … the associated producers govern[ing] the human metabolism with nature in a rational way. … The true realm of freedom, the development of human powers as an end in itself, begins beyond it. … The reduction of the working day [in material production] is the basic prerequisite’.20 I speak of freedom in our unhappy epoch where millennial class society is breaking down yet redoubles its tenacious hold in its death throes (to which I shall return under the rubric of repressive intolerance), while the truly free society of the associated producers cannot yet be born. In this most dangerous interregnum of ours, the arts and imagination in general register deeply and durably both the disalienated horizons and the fullness of human alienations. As an extraordinary passage by Simmel has it: ‘the intellect is egalitarian and as it were communist’, for its contents are both generally communicable and, if correct, generally shareable ‘by every sufficiently educated mind (Geist) … and the potential infinity of disseminating theoretical imaginations has no influence on their meaning, [so that] they exclude private property’.21 Simmel is probably echoing, with more prudence in more complexly alienated times, Plato’s equally astounding proposition in Meno that any slave is capable of understanding geometry.22 Centrally, disseminated fiction’s contract with the reader is ‘not just egalitarian … [but constitutive of] the story-teller’s art itself. The moral of the very act of fabulation was the equality of the intelligence’.23 Such astriving for freedom through understanding, assumed from Aristotle to Rousseau as a natural human right though often unnaturally suppressed,is here discussed within ‘word art’, literature in the widest sense of all oral and written instances, and taking as its pars pro toto narrative agents, with a focus on theactant as arbiter.

Among the structurally necessary functions of narrative agents, as pioneered by Vladimir Propp and Claude Lévi-Strauss and worked out in many variations from Étienne Souriau to Yuri Lotman, the most important for the narrative horizon and the outcome of events is the actant as Mandator or Arbiter. Usually called Destiny, as the Greek ananke it was a religious (mythical) notion fusing violent power with transcendent necessity, best codified at the outset in the Oedipus myth and plays. But historically hegemonic necessity may change, as already foreshadowed by Sophocles’s Antigone, nostalgically loyal to the old values, and in overtly subversive fashion by Aeschylus’s Prometheus, for the moment – a long historical age of class society – bound. Thus, the opposition of freedom and destiny can be used as one key to the interplay of the posited intra-textual and the presupposed extratextual elements of narration.24 This interplay varies according to the writers’ and readers’ structures of experience and feeling about force relationships in history. In what I call metaphysical genres like horror or heroic fantasy – and ever more so in myth – Destiny is sovereign; in early bourgeois ‘realism’ and SF it is not – characters and its actions, successful or failed, are decisive. This means that the SF plot is typically open or ‘epic’, where the plot of metaphysical genres is typically closed or ‘mythic’.25

In the Middle Ages, Destiny was subsumed under the equally capricious and numinous monotheistic God.26 But the corrosive hegemony of bourgeois individualism downgraded Destiny and annexed it to the – more or less typical – individual conflict of the Protagonist’s vs. the Antagonist’s wills and forces. This was, in a way, a huge liberation from under an idealised Mycenean (later feudal) Lord (anax, Dominus). Such a liberation was foreshadowed in the best Athenian rebels: from the quite explicit and programmaticalPrometheus Bound to the less monolithic but still exemplaryBacchae. But this latter play already prefigures the downfall of the free aspect of the polis, overwhelmed by the slave-owning empires, whose defeat finally bred Christianity as a realtertium datur: slavery, oppression, and misery on Earth, freedom, equality, and bliss in the heavens. This illusory compromise collapsed with the dominance of merchant capitalism. Modern SF after Verne and Wells, at its best, shared the liberatory aspect of bourgeois realism – nothing is foreordained, it all depends on the situation and the actions within it, mainly by our Protagonist: Ursula Le Guin’s Shevek, or Philip K. Dick’s Hoppy, or the Strugatsky brothers’ explorer hero with many names. At any rate, from the nineteenth century on, the ideological master code of industrial society became History as Destiny and Power, I found in a depth in investigation of SF in the United Kingdom between 1848 and 1885.27 True, an open ending does not, again realistically, lead to necessary success: within the spread of SF horizons between eutopian and dystopian, it may well lead to utter defeat. But the defeat is as a rule causally explicable and contingent rather than destined: it can be undone by other actions and/or other situations, in the same Possible World or other ones.

What happens to Destiny in these last three or four decades of boundless financialised imperialism, under the new hegemon of existential anti-utopia (registered early on by some of us, most prominently by Jameson)? It is omnipresent and inescapable as its grimmest ancestors were, from Zeus and Yahweh on, it punishes by death and torture as they did, but it has also grown actantially invisible – a hidden yet powerful God, not posed or explicit but presupposed and structurally necessary in order to make readable sense of the stories. In what one should concede is a masterpiece of monolithically successful inculcation by massified means, anti-utopia instils its theology tacitly. It is the system of feral social Darwinism where the strong man fights and the weak man dies, the allegorical ‘Man’ standing both for machismo and for entire human groups and classes.28 As usual, the Nazis’ ‘racial’ theory, flying in the face of the fact that there are no races within the speciesHomo sapiens sapiens, carried this system to its ultimate and clearest extreme; however, in their situation of incomplete hegemony the Arbiter had to be biologised and enforced by both open and hidden mass murder. It is much more economical for globalised capitalism to enforce it by misery plus tacit assumptions that cannot even be noticed by the mass reader or TV consumer, though ongoing structural violence causes tens of millions of premature deaths, while tens of thousands of outright murders whenever rebellion rises are an indispensable complement.

This, as it were, Destiny degrades power struggles between people into total inhumanity, well emblematised in the SF militarists’ predilection for ‘Bugs’ or Bug-Eyed Monsters, that have to be squashed as rats or bacteria (pardon me, viruses) – see Heinlein at his most virulent in Starship Troopers and the movie adaptation by Paul Verhoeven. The old adage ‘hate the sin not the sinner’ is swept into oblivion, physical repression by hunger, untreated pandemics or the bullet is getting to be the order of the day. Going Marcuse one better after the demise of the welfare state, we have to update his 1960s concept of repressive tolerance intorepressive intolerance, sometimes masquerading as repressive quasi-semi-demi-tolerance. If God and communism are dead, everything is allowed, we do not really need all those silly parliamentary masks anyway, Twitter and violence suffice (personifications: Trump, Bolsonaro, and the mini-dictators in size but not cruelty from the East European bosses Orbán and Kaczyński to general el-Sisi and the hereditary Kim).

3.2. Anti-utopia as norm: closed horizon and infiltrating form

US SF, as a whole, was, for four decades, from the New Deal on, sociologically based on an ascending middle class that began rapidly falling behind, falling down in power and confidence, and falling apart; and in particular, on the intellectuals (the apprentice ones from roughly 13 to 25 years, and the adult ones after that age). The closing of the Golden Age of SF and its implied utopianism can be precisely dated to ca. 1974,29 the end of the anti-war and Black protests in the USA and the beginning of an initially slow but soon strengthening Right-wing offensive. US SF was always ideologically ‘two-souled’, and it was further hollowed out both by the Zeitgeist and by a well-funded turn to militarist fiction.30 True, feminist utopias held on significantly longer and were in the 1980s joined by the best cyberpunk, since both had important and active constituencies – US and European feminists, as well as the new media and internet intellectuals of the globalising North. But these two important dissident movements proved too isolated for a successful counter-offensive, especially since SF was getting downgraded into a poor relative of Tolkien, Conan, and horror fantasy.31 This made for a social-Darwinist reduction of history to a point-like eternity where only quantities matter and fashions change, squarely aimed at expunging the indelible ‘amphibiousness’ of a utopia that participates in the present and in the (possible) future.32

Intellectuals are two-souled, oscillating between the rulers and the ruled, the exploiters and the exploited; this can be registered in US SF, as I’ve discussed elsewhere.33 I saw the opposed poles as being a destructive soul focussed on adolescent fears, technological fixes, violence and war – exactly like today’s Trumpists – and a cognitive soul focussed on salvation, where truth shall make you free (if you recognise and practice it). In other words, the intellectual’s need for freedom and control over one’s own product, in order simply to ply his or her trade, may be oriented either toward a liberatory hybrid between citoyen and comrade, or toward dreams of a new ruling class in their own image. The latter can be well seen in their grasping for alternative yet quite hierarchical power systems, pioneered by the ambiguous Francis Bacon and the more resolutely closed Tommaso Campanella, where the adumbrated worlds are either a rigid lay monastery or a rigid research science set-up.34 Utopias by intellectuals (are there any other ones?) also demonstrate a taste for closing systems, as Roland Barthes found, or more precisely an anti-cognitive ideological aspect, fortunately, in the best cases, recessive rather than dominant.35 All these were easily squelched by commercial capitalism and absolutism, well shown by More’s fate as an epochally significant but failed political heresiarch; and his ‘first new image of the role of the intellectual’ since Augustine of Hippo, the glimpse of humanists as a new ruling class, was definitively downgraded by the industrial grande bourgeoisie36 which created the prevailing image of utopia as synonym of the impossible and ridiculous.

Enter, at the turn of our twenty-first century, anti-utopia, a subject so new and so important that it will bear revisiting. My thesis is that anti-utopia as horizon and form is a major novelty, related to the fact that its original bearers are not only and not primarily professional intellectuals but professional politicians, the state apparatus of violence and its embedded think-tanks. Anti-utopia is the latest crown for the ruling classes’ repressive tradition, evolving in my generation from welfare-state pseudo-tolerance into intolerance. Intolerant repression was always the material truth of violent power. Lately, it ranges from refusal of money and careers for deviant thinkers, proclaimed unthinkably confused and/or dogmatic (!), to incarceration (probably the case for a great majority of officially assumed ‘terrorists’, if we are to judge from the US criminal justice as applied to the poor, beginning with the visible ‘others’ of women, Blacks, and immigrants). It ends with assassinations, so frequently instanced in US politics by the Kennedys, the leadership of the Black Panthers’, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and many humbler people under the media radar. Anti-utopia is the horizon that holds that all central power and ideological pillars are untouchable, like Yahweh: I am that I am; but it is also the vector of intolerant repression in order to eternalise the ruling system as the best possible one. The ruthless saturation of imaginary space in an eternal present makes anti-utopia’s grip very powerful indeed.

A revealing light is thrown on the genesis and form of anti-utopia, and on its rise to the age’s doxa or common sense crowding out Destiny, by the new political ontology of the US ruling class – and to a degree all rulers of its allied and even enemy states – after 9/11. In this oligarchic ontology, imagination directly issues into factual states. Whether the US federal government really feared a worldwide ‘Islamist’ insurrection or simply used this as a godsent opportunity to invoke ‘Homeland security’, creating in 2002 the titanic eponymous department, what it also excogitated and engaged upon was the evilnovum of ‘a parallel ... extra-legal universe’.37This was an alternative, largely secret and hidden world obeying new procedures of violent power and creating new spaces for it: on the one hand ‘extraterritorial rendition networks, prison archipelagos, and secret “black site” facilities’, on the other, ‘indefinite detentions, military tribunals, and executive circumventions of national and international law’ permitting planned kidnappings and killings of anybody the central security agencies deemed important enough.38 This parallel world in the interstices of our everyday one ruthlessly jettisoned not only basic principles of international law but the whole of lay theory and practice of humanist-cum-liberal history and culture; that is, it jettisoned the revolutionary citoyen values in favour of a blend of slave-owning empires, colonial subjugation, the Holy Inquisition, and strictest World-War-type secrecy and disinformation. It is the best empirical approximation to Lovecraft’s vague but malignantly powerful Dark Gods.

Two factors seem to me central here: first, the establishment of what Elaine Scarry calls an alternative universe with different permissibilities – ‘different bases for fact, standards of proof, evidentiary parameters, rights, procedures, penalties, guarantees, and expectations’.39 It fits well the urge of rulers in late capitalism for the state of exception or a de facto martial law, applicable at will and in piecemeal fashion. This was theorised most clearly by the Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt, undergoing a revival at those times, and observed also by Judith Butler within a critical Agambenian frame. However, Butler goes one important step further, noting that it is ‘a paralegal universe that goes by the name of law’.40 For the second defining factor of the existential anti-utopia systematically developed from within the nuclei of our ruling classes – and zealously followed by (sad to say) very many intellectuals right down to a tacitly new understanding of dystopia as cynically inevitable – is that this new universe is not openly affirmed, as in its four historical predecessors identified above and their culmination in Nazism; on the contrary, it propositionally and axiologically splits off from the official universe, still ruled by publicly accessible contracts and remaining in force for the docile masses of the ruled (in the more affluent North, at least) insofar as they remain exploitable or otherwise usable. The secret world works by covertly yet systematicallyinfiltrating the overt one, in which it is revealed first by macro-events that cannot be denied (but can be misnamed), such as the mass bombings from Afghanistan and Serbia to Syria or Libya, and then by the occasional courageous whistle-blower, who is made to pay dearly: from Frank Snepp (CIA, 1977) and Mordechai Vanunu (Israeli nuclear weapons, 1986) to John Kiriakou (CIA 2007), Chelsea Manning (US Army, 2010), Edward Snowden (NSA, 2013) and so on.41 Were there space, I would undertake to show that existential anti-utopia is the left hand of darkness, whose right hand is the incessant murderous warfare of late capitalism which has never stopped from 1914 on. It is indeed warfare that in our Capitalocene first clearly grew into the substitute for liberatory politics and the unacknowledged economical pillar of the system.42

I concluded, in my ‘What Existential Anti-Utopia Means for Us’,43that anti-utopia was a targeted and embattled ideologico-political use of a closed horizon to render unthinkable both the eutopia of a better possible world and dystopia as an awful warning about the tendencies in the writer’s and readers’ present. Anti-utopia stifles not only the right to dissent but primarily the desire for radical novelty – in brief, it dismantles any possibility of plebeian democracy. This was a world-historical novum by which the ideologico-political development of capitalism, that had all along produced fakenovums galore, morphed by the beginning of twenty-first century into this encompassing monster – existential anti-utopia as a super-weapon. One of its pillars was the Cold War misuse of 1984, whose ambiguities, weaknesses, and plain errors44 allowed its use for proving that any alternative to capitalism would be even worse. I think Orwell himself would be horrified by the horizon of a world where all people and human possibilities existed only as adjunct exploitable labour for profit or as mercenary servants.

3.3 Violence vs. care: an ending in creation

I could think of several worthy ways in which to end an article on these concerns, but one stark dichotomy seems most useful: the one between Violence and Care in relationships between people, including their metabolism with nature.45 On the side of Violence is Class Power and Embedded Science, on the side of Care is Liberating Knowledge.46 Violence, as part of the semantic cluster of ‘power in operation’,47 is one keyword of any political epistemology. I have discussed it at some length,48 concluding that power (Macht) is inherent in any interhuman situation or politics, whereas violence (Gewalt) is predicated on the manifold tensions between and inside groups or classes of dominators and dominated. I defined as violence psychophysicallesion of people, usually with irreversible traces, deviating from the hegemonic British sense of ‘opposition to legal power’.49 Economic harm to commodities or other property may well be destructive and punishable, but it constitutes violence only if it leads to wounds, hunger, or similar. Capitalism can only exist by means of a ceaseless and pitiless ‘primordial accumulation’ violently ruining the lives of entire subordinate classes, as exemplarily posited in Marx’s pages on sixteenth-century England and re-actualised byRosa Luxemburg even before the World Wars and other globalisations. The permanent violence needed for the accumulation of capital was consubstantial with militarism. Much the largest amount of violence is to be found in ripe capitalism due to high-technology wars which have in the twentieth century caused at least110 million deaths;50 I would include within the ambit of violence severe psychic lesions, from prolonged stress to terror, which victimises hundreds of millions. While all violence is contemptible, it can be divided into individual, group, and state violence against people, and, as a rule, state violence towers above the group one by a factor of circa 2,000 to 1. Mutually reinforcing causal factors of violence are state violence, omnipresent everyday alienation in work conditions and its repercussions on all human relationships, as well as other forms of ‘structural’ or ‘systemic violence’ – such as extreme poverty leading to death by hunger and/or avoidable diseases, at present threatening more than three billion people.

Are there situations when violence is justified, and if yes, for what ends and in which measure?

First, not all violence, whatever its excuse may be, is permissible: for example, killing civilians in declared or undeclared wars, or any torturing. All violence testifies to a profound sickness of the system and persons generating and using it. Nonetheless, self-defence is recognised by most historical systems. If it aims to counteract and minimise societal violence as a whole and to diminish its causes, this may justify counter-violence. I have come to the conclusion – as finally did Thoreau, Martin Luther King Jr., and even, it seems, Gandhi – thatcounter-violence is not so hurtful as the want of it. When individual and communal human rights are routinely violated, oppressed people can and should react, first by using their power of disbelief, in order to recognise the disinformation and cultural lies used to keep them in their place, and then by coming together in collective action. For,central to and constitutive of violence is a denial of personal psychophysical integrity and therefore of freedom as a basic human need and right. It amounts to an overt or covert racism that classifies certain types of people as not Us but Them, so that inhumanity in their regard can be masked, denied, and induced as normal. In particular, counter-violence is inescapable in situations involving armed repression by the police, military or private mercenaries. A strict differentiation between justifiable and unjustifiable violence then becomes mandatory; it necessarily centres on state-militarised repression but should also include reactive groups and individuals internalising the institutionalised violence. Even when forced counter-violence is permissible, it is fraught with long-range dangers, so that keeping it to the necessary minimum must remain a permanent objective.

The central argument has been most memorably formulated in the final two articles of the Jacobin Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793:

Article 34: The societal body is oppressed when any of its members is oppressed. All members are oppressed when the societal body is oppressed.

Article 35: When government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is the most sacred right and the most indispensable duty of the people and of any part of the people.

In conclusion, I would go further and claim that violence and creation (poiein), are the two opposed poles of power. All creation, the domain of de-alienation, relates to people and values. It does so directly ascare, and indirectly asunderstanding about situations and the causes of events. Taking a cue from Ricoeur’s note that human beings are “designated as a power to exist”,51 I would tabularise the following alternatives:

VARIETIES OF THE POWER TO EXIST

| UNDERSTANDING/SEEING Histories of Friendship: On Christopher Chitty's Sexual HegemonyBy Asad Haider Maurice Blanchot wrote in a tribute to his friend Georges Bataille, a decade after his death, that friendship “does not allow us to speak of our friends, but only to speak to them.”1 Chris Chitty was my friend. As I read his posthumous book Sexual Hegemony, which comes to me in his absence, I cannot help but speak to him. And I have tried to remember when we spoke to each other, as he passed the time he was given on earth. A life leaves traces after its end, but most elude our grasp. With my own passage of time, I have come to think they become the warp and weft of memory and loss which weave the fabric of a life that continues. As I tried to access these memories, I had to pose myself the question of whether to review the writing that had been exchanged between us. Initially I decided that I would deliberately leave these traces unseen, and unthought. Yet I eventually found myself combing through every trace that remained. I expected mainly to find vigorous intellectual exchanges. Certainly, I found those. But I also learned that, in the strange operations of the unconscious, the psychic toll of his last days and death had suppressed memories of the time we had spent together, which was much more than I remembered, and the genuine intimacy and conviviality between us. I was reminded, too, of his political interventions, which in writing consisted primarily of commentaries and proposals regarding university austerity and the labor conditions of instructors. I found no record of the discussions between us that arose in the moments of eruption, when early mornings were spent on picket lines and buildings were occupied, or the rest and refuge we took in his apartment after long nights on the streets, as we set off together on the arduous and aleatory path of the movement. We met as graduate students in History of Consciousness at UC Santa Cruz, both interested in Marxism and both interested in the work of Michel Foucault. Unlike many others, we viewed the encounter between Marx and Foucault not as an antagonistic confrontation, but as a kind of swerve which made a world. I approached Foucault as one instance of the broader French intellectual and political scene of the 60s and 70s, and it was primarily through French Marxism that I staged the encounter, in which questions of method and politics were transversally posed. Chris had deeply absorbed himself in Foucault’s work itself, and moved through it into dialogue with Marxism on the division of labor, technology, political economy, the family, and the state. Engaged in a polemic against the anti-Marxist sectarianism of depoliticised academic “Foucauldians,” while, at the same time, trying to demonstrate to Marxists that Foucault had made a singular contribution which could not be dismissed from the vantage point of a fictive Marxist orthodoxy, Chris already had his work cut out for him. But he also sought to follow the example of Foucault rather than simply commenting on him or “applying” his theories, and this meant conducting fine-grained research into changing power relations in the transition to capitalism, as Foucault explicitly saw himself doing since History of Madness.2 When dealing with a certain kind of Marxism, this presented methodological ambiguities, which Foucault himself had wryly noted. Those who, like Jean-Paul Sartre, accused Foucault of the “refusal of history” seemed never to have set foot in an archive.3 Closer to the Marx who sat on his carbuncles in the British Museum was Foucault, who from the very beginning wroteHistory of Madness immersed in the “slightly dusty archives of pain.”4 In the Marxian register captivated by the idea of history, yet unburdened by historical research, the microscopic detail typical of Foucault’s practices of archaeology and genealogy could become little more than evidence for causal historical claims guaranteed in advance by a general theory, necessary expressions of a predetermined historical totality. The task Chris set for himself was to write about Foucault, and to write about Marxism, and, from this overlapping conceptual standpoint, enter into the archive to write a different kind of history of homosexuality. I had the fortune of many discussions with Chris on the broad contours of his project; in one memorable case, he told me about his research into the history of homosocial male spaces as we changed clothes in the men’s locker room of the UCSC gym. The publication of the first volume of the History of Sexuality in 1976 inspired countless attempts to formulate a theory of the modern constitution of homosexuality. The difficulty of this task is perhaps best illustrated by none other than Foucault himself, who immediately entered into a year of apparent intellectual silence. He returned with a marked change in his approach, and would not publish another book until just before his death in 1984: the second and third volumes ofThe History of Sexuality, which abruptly turned the reader to a study of ethics, truth, and the self in antiquity, and announced a shift from the analysis of power to the analysis of “the subject.”5 It was the very category he had ruthlessly criticised for decades – another axis of dispute with Sartre – but which he now sought to rethink in an entirely novel way. As we will see, Chris had profound insights into these developments in Foucault’s thought. There are many reasons why projects remain unfinished. I have the impression from my discussions with him that the scale and ambition of Chris’s project demanded a series of studies, beyond the scope of a single dissertation. But there is something constitutive about incompleteness, as the examples of both Marx and Foucault attest. As Blanchot put it in “The Absence of the Book”: “To write is to produce the absence of work.”6 In his first great book, Foucault used the phrase “absence of work” as the definition of “madness.” It is likely he was recalling a figure almost lost to history: Jacques Martin, who, along with Louis Althusser, formed Foucault’s closest circle of friends at the École normale supérieure in the late 40s. InHistory of Madness, the absence of work was also a theory of history itself: of that which is rejected by a civilisation as useless and unintelligible, and thus makes history meaningful by constituting its limits. For Foucault, the production of the categories of madness and homosexuality rended the dialectic of history; Martin’s experience was located at both of these limits. Unable to write, Martin called himself a “philosopher without work,” a label he realised by destroying his own papers. Facing the prospect of a lifetime of confinement, Martin’s struggle culminated in his tragic suicide.7 Thanks to the publication of Sexual Hegemony, Chris Chitty is not a philosopher without work. But it is the absence of work which I am unable to forget: not only everything he did not manage to write, every conversation we never ended up having, but also the question of history and its limits which pervades the traces he left. In another moving tribute, Blanchot wrote that “friendship was perhaps promised to Foucault as a posthumous gift.” He said: “In bearing witness to a work demanding study (unprejudiced reading) rather than praise, I believe I am remaining faithful, however awkwardly, to the intellectual friendship that his death, so painful for me, today allows me to declare to him.”8 It is this Foucault who, in his investigation of truth-telling in his final years, will make note of “the obligation to be frank with one's friends.”9 My faithfulness to this friendship is to speak now to Chris Chitty, and to speak frankly, as a matter of ethics, in tribute to his own thinking of and as the subject of truth. And, so, I turn first to my own archives. *** I found exchanges with Chitty in 2012 revolving around his translation of Foucault’s 1976 lecture “The Mesh of Power,” which he published in Viewpoint along with a detailed and original commentary that was immediately an outstanding success and has since been widely cited.10 On rereading, I find it magisterial. Chitty had mastered the whole scope of Foucault’s work, in its notoriously inscrutable convolutions and changes in terminology, identifying not only the shifts themselves but also what was at stake in them, operating not only at the level of the concept but also of politics. Thus, Chitty situated Foucault’s shifting thought in his participation in the struggles of the 60s and 70s, with a political and theoretical acumen that should embarrass those who blather about whether the fact that Foucault read Gary Becker made him a closet neoliberal. In dialogue, Chitty and I worked out our thinking. Reviewing my own positions, I do not always agree with myself, though often I do. The crux of the discussion: Chitty insisted to me that it was necessary to pose a dialectical question regarding Foucault’s thought. This was because Foucault studied, first of all, vestigial forms of power, but then went on to show how new political rationalities, or technological organisations, were grafted onto these older edifices. But the followers of Foucault, he argued, had failed to measure up to these questions because they had rejected the possibility of thinking them dialectically. He attributed the needed dialectic to Marx, meaning that only Marx’s theory could explain how the residual forms of power of political economy and the state continued to exist after the end of 19th century capitalism, and, indeed, how existing political forms might survive a transition out of capitalism. I did not agree with him then because I believed in the necessity of rejecting the dialectic of history, which so many enemies of the dialectic have ended up reproducing. I thought, and still think, that the historical dialectic cannot deal with this problem, because it is concerned with supersession, and not with survivals, vestiges, or residues. Nevertheless, already thirty years ago, Judith Butler asked, in a perceptive analysis of Foucault in the context of the reading of Hegel, if anti-dialectical positions are “still haunted by the dialectic, even as they claim to be in utter opposition to it.” As Butler points out, Foucault criticises a Hegelian philosophy of history “inasmuch as the dialectical explanation of historical experience assumes that history manifests an implicit and progressive rationality.” Accordingly, he questions the historiographical assumption that “the origin of an historical state of affairs can be found and, if found, could shed any light on the meaning of that state of affairs.”11 Yet Foucault, Butler suggests, nevertheless remains a “tenuous dialectician,” insofar as his is “a dialectic without a subject and without teleology, a dialectic unanchored in which the constant inversion of opposites leads not to a reconciliation in unity, but to a proliferation of oppositions which come to undermine the hegemony of binary opposition itself.”12 How such distinctions might have generated a different dialogue in response to Chitty’s dialectical injunction, I will never know. What is striking to me now is that the carefully refined text Chitty finally placed on my desk expelled the question of the dialectic entirely. He expressed no regret about this. The prevailing theoretical discourse had sutured the question of the dialectic to the polarisation between Marx and Foucault; Chitty took up a position in the battlefield of philosophy which opposed the very framing of this question. In an exchange which followed soon after the publication of his article on Foucault, Chitty pointed out that the dialectical mode of historical thought, which he associated with Sartre but said was rooted in 19th century discourse, posited a set of speaking subjects at the centre of the historical process, which was precisely the existential subject. Foucault, in contrast, while posing the same questions regarding the construction of thought and sequences of thought, took the perspective of a moment in which the speaking subject could no longer be established as the driving force of an individual psychic history, or for that matter as the driving force of history as such. It was technology that decentred the subject, because, at a certain historical stage, the technological organisation of society began to matter much more than what people thought or said about it. Because 19th century discourse was unable to grasp the role of technology in the industrial age, Chitty said that Marx had failed to develop a theory of the material force of ideology, while Hegel had to attempt to hypostatise human consciousness in the form of the “world-historical individual.” Foucault, in contrast, theorised the scientific and technological neutralisation of the speaking subject. His challenge to Marxism, then, was that a “theory of praxis” could not capture the way technology had begun to program subjectivity and impose limits on collective agency. Studying the history of industrial society now required us to capture new phenomena, namely the category of the population, and so Foucault abandoned his previous idea, which Chitty attributed to The Order of Things, that history was a “process without a subject.” Now the population became the subject of history, thus presenting the possibility of periodisation, and with the method of genealogy Foucault surpassed the archaeological opposition between continuity and discontinuity. In my view, this reading presents us with a historicist Foucault, indeed a Foucault who had, despite his stated intentions, returned to the historical dialectic. Yet, at the same time, Chitty argued forcefully against a historicist reading of Foucault, the reading that Sartre himself had presented in response toThe Order of Things, which turned his thought into a mere expression of an alienated and technocratic society. Chitty explained his rejection of this reading by arguing that the history of categories and thought forms refers to things which formally exist between us and reality, rather than being purely objective or purely subjective. It was, instead, a matter of a dense and historical combination of the two. As I read this now, I see two possible dialectics. At first, we have a “dialectic unanchored,” a logical dialectic for which historical thought is the relation between thought and the history of thought. But then we have history as the historical combination of the objective and the subjective, the historical dialectic, in which case we have a subject of history. *** Reviewing Chitty’s work I was struck to find that in a talk at the Historical Materialism conference in New York the year after our exchange, he now affirmed that, for Foucault, history remained a process without a subject.13 This term – which, to my knowledge, Foucault does not use – was introduced in passing by Étienne Balibar in the 1964-5 Reading Capital seminar (though of course the words may have been uttered earlier unrecorded), but was only developed three years later by Althusser in a talk called “Marx’s Relation to Hegel” at the seminar of Jean Hyppolite.14 In posing the question of Foucault’s adherence to the concept of history as a process without a subject, Chitty was pointing to a fundamental methodological problem. In The Order of Things, Foucault had indeed shown that the subject of Man is a discursive effect which is coming to be displaced by a new order of knowledge. It was also precisely in the critique of the anthropological conception of history, of history as the process of alienation of the subject of Man, that Althusser formulated the concept of the process without a subject. Provocatively, Althusser credited Hegel himself with this concept, since for Hegel the subject of the historical dialectic is not Man but the dialectic itself. The insertion of Man as the subject of history by Feuerbach and the young Marx was not a viable materialism; it could not measure up to the systematic power of Hegel’s idealism. The real difference between Marx’s materialist dialectic and Hegel’s idealist dialectic, Althusser argued, was not that the form of dialectics was applied to a different substance, which would after all be an entirely non-dialectical formulation.15 It was, rather, that, for the materialist dialectic, the historical process was no longer directed towards the telos of Absolute Knowledge, and therefore, as he would later elaborate, was also a process without a goal.16 But this was not due to a historicalground for history, identified by a subject of knowledge which, in a kind of circle, would also be generated by that same historical ground. (This circle can be taken as a geometrical definition of historicism.) It was, instead, theconcept of history, which was the product of a break in knowledge resulting from theoretical labors which had no relation of necessity to their historical time. That is the concept of history as a process without a subject was a constitutive condition and limit of knowledge of history, which Marxproduced through theoretical work rather than byexpressing his historical period in thought. To posit that historicity emerges at a historical moment, which amounts to saying that it becomes available to a subject of knowledge that had to already exist and be oriented towards this goal, would be to regress from the Marxist to the Hegelian dialectic. The idealist dialectic is only possible on the basis of what Althusser had earlier characterised in his paper for the Reading Capital seminar as the “homogeneous continuity” and “contemporaneity” of time. Thehomogeneous continuity of time “is the reflection in existence of the continuity of the dialectical development of the Idea.” For this conception, historical analysis consists of the “division of this continuum according to a periodisation corresponding to the succession of one dialectical totality after another.” Thecontemporaneity of time is the structure of the “essential section”: “an intellectual operation in which avertical break is made at any moment in historical time, a break in the present such that all the elements of the whole revealed by this section are in an immediate relationship with one another, a relationship that immediately expresses their internal essence.”17 In contrast, for the materialist dialectic, making a cut in history would reveal different levels with different temporalities – political, legal, ideological, and economic levels whose times, breaks, rhythms, and punctuations would not correspond.18 From this vantage point, Foucault presents us with several difficulties in The Order of Things, despite his stated opposition to both the dialectic and to historicism. The “episteme” appears to be an essential section, in which all knowledge is necessarily its expression. Because of Foucault’s emphasis on discontinuity, it might appear, as it did to Sartre, that these are simply static and disconnected images. But, in fact, it is difficult to see how such “ages” can be periodised without reference to a homogeneous and continuous historical time. Furthermore, since the standpoint from which Foucault studies the episteme remains unspecified, and yet it is the modern episteme which gives rise to historicity itself, it is not clear how we can avoid returning to the historicist circle of the subject. We run the risk of either allowing for the possibility of a subject which is outside history altogether, or restoring the subject of history. In the unfinished work of Sexual Hegemony, I see Chitty working through these very problems. He engages in the complex staging of conceptual conflicts internal to his own framework, and in this displays the exceptional combination of creativity and erudition which characterised his intelligence. A careful reading of the incompleteness of his text, its distance from resolution, a refusal to fill its empty spaces with ideological plenitude and to resolve its points of heresy into harmonious reconciliation, is what will allow us to pose the questions which otherwise remain obscure. *** The question of history in Sexual Hegemony is closely articulated with differing conceptions of capitalism. Chitty’s “hypothesis concerning the relation between sexual repression and the origins of capitalism” has a powerful attraction today, but the concepts it implies are not simply given by the empirical data; they must be constructed. The visible presentation of this hypothesis is situated within “the longue durée of sexuality, social form, and economic development” – a reference to the historiography associated with the Annales school, represented in the book’s footnotes by Fernand Braudel.19 Foucault noted at the beginning of The Archaeology of Knowledge that this new writing of history displaced the subject with the vast sedimentary strata of geography and demography. But it did so within the frame of historical continuity, in contrast to the emphasis on discontinuity that was characteristic of Foucault’s own previous work and new developments in the history of the ideas.20 The tension between continuity and discontinuity pervades the trajectory of Foucault’s historical method, and it also appears in the conceptions of capitalism in Sexual Hegemony. The following passage points us to the visible and invisible questions at stake:

While the word “capitalism” does not appear in this passage, the word which gives us access to the invisible questions of the text is “correspond.” Correspondence is the master concept which regulates the visible historical analysis in Sexual Hegemony. In TheArchaeology of Knowledge, where the unresolved questions ofThe Order of Things are taken up in a new discourse on method, we find indications what this word means for historical analysis. The first indication comes when Foucault defends himself from the criticism that The Order of Things reduces every phenomenon to a necessary expression of its historical period. Foucault argues that his conception of a “discursive formation” does not follow such rules of historical necessity – in fact, it is subject to modifications made possible by its system of “strategic choices.”22 The discursive formation “does not play the role of a figure that arrests time and freezes it for decades or centuries,” as critics like Sartre had charged. It, rather, “determines a regularity proper to temporal processes,” presenting “the principle of articulation between a series of discursive events and other series of events, transformations, mutations, and processes.” Therefore “it is not an atemporal form, but a schema of correspondence between several temporal series.”23 The second indication comes when Foucault attempts to distinguish his work from the history of ideas, even though he had initially identified it as the site of new histories of discontinuity. Now, Foucault entirely associates the history of ideas with traditional forms of historical analysis, defined by “genesis, continuity, totalization.” It is the analysis of “distant correspondences, of permanences that persist beneath apparent changes, of slow formations that profit from innumerable blind complicities, of those total figures that gradually come together and suddenly condense into the fine point of the work.” Foucault’s “archaeological description” is a radical alternative to this history of ideas.24 To use his own terminology, Foucault has mobilised the word correspondence within two distinct strategies. First, he uses it to show that the discursive formation is neither static nor the necessary unfolding of a historical origin, because it is the analysis of correspondences between several temporal series. Second, he uses it to show that the history of ideas remains within the traditional form of history, because it is the analysis of correspondences between permanences that constitute the unity of the work. Correspondence is doubled here, representing at the same time the discontinuity and dispersion of multiple temporalities described by archaeology, and the continuity of the unitary temporality of the traditional conception of historical continuity. Another term, however, which appears and reappears in entirely different contexts in TheArchaeology of Knowledge, establishes a marginal tension with correspondence. This word,décalage, which I will, for the momen,t translate as discrepancy, is not easy to detect, because it is never presented systematically and frequently appears in lengthy lists including words like series, cuts, limits, levels, specificities, forms, relations, temporalities, remanences, modifications, analogies, differences, hierarchies, complementarities, coincidences, thresholds, succession, disconnections, dispersions, ruptures, and scansions.25 In this barrage of terms, it is not self-evident why each one is necessary, whether they are compatible with each other, or how they help us understand what is distinctive about archaeology. In the English translation, matters are even less clear, because the term is rendered as both “shifts” and “gap,” and on one occasion is omitted.26 To these translations, along with “discrepancy,” we could add “lag” and “delay.” In Reading Capital, where it is used constantly by both Althusser and Balibar, it has been translated as “dislocation.”27 This usage of the term is fundamental, because it grasps precisely the historical problem Chitty posed to me, of the grafting of new forms onto the vestigial edifice, a phenomenon which is actually inexplicable in the linear and unitary temporality of the historical dialectic. In the transition to capitalism, Balibar points out, the existing forms of the law and the state are not expressions of the emergent economic structure – this would be a teleological absurdity. Yet their power and organised force facilitate and accelerate the capitalist transition. As Balibar writes: “this dislocation can be translated by saying that the correspondence appears… in the form of anon-correspondence between the different levels.”28 That is, it is not a non-correspondence which is resolved into correspondence, but a constitutive dislocation which Althusser calls the “intertwining” of multiple temporalities in the historical process.29 Thus dislocations cannot be measured against a single continuous time, and the radical implication is that “there is no history in general, but only specific structures of historicity.”30 To return to the question of historical knowledge, it is in precisely the same sense that there is a dislocation between knowledge and history, not as an expression in thought of a historical moment but as a structure of historicity. This dislocation, which might now be more clearly stated as a discrepancy, rules out the possibility that knowledge simply corresponds to history, that it expresses history in the manner that we might be tempted to say that any ideological phenomenon is the expression of the historical stage of the economic structure. Notwithstanding his moments of historicist restoration, Foucault’s project also begins with the critique of the notion that the process of cognition emerges from the identity between the subject of experience and the subject of history. With this starting point, the subject is always decentred, because we have no extra-historical vantage point from which to identify a historical period and determine that a particular kind of subject is its expression, and there is no subject of history whose self-consciousness constitutes historical knowledge. As he attempts to maintain this position over time, Foucault constantly passes through discrepancies; by considering them seriously, The Order of Things, too, as Balibar has since demonstrated, can be read otherwise.31 *** We have established the fundamental relation between capitalism and history and its consequences for historical knowledge. The conception of capitalism which introduces the theory of correspondence in Sexual Hegemony is the historical continuity of trade as it extends across the world-system over the course of seven centuries, comprising cycles of financial and material expansion in Florence, Venice, Milan, Genoa, Amsterdam, London, and New York. However, another capitalism emerges later in the text, when Chitty writes:

According to this conception, capitalism emerges primarily within two centuries in the English countryside, as the result of struggles within feudal society. As Chitty writes, this account “shifts focus away from a deterministic account” towards the “contingent features of the transition to capitalism.”33 Peasant revolts provoked landlords to consolidate and enclose their land and lease it to competing tenants, separating people from their means of subsistence and ultimately forcing them to sell their labor-power for a wage. Within this new capitalist class structure it became possible for property owners to extract a surplus from labour and accumulate capital. This is a theory of discontinuity, insofar as capitalism is now a historical rupture whose specific social relations of trade, division of labour, and accumulation cannot be used to explain its own emergence. The geographical and temporal specificity of the transition to capitalism could, furthermore be taken as a kind of historical nominalism. However, it is possible for the category of “property relations” to reintroduce both historical continuity and a general theory of history, if it is a historical invariant built on a transhistorical foundation. In the classical and now more or less discredited model of dialectical and historical materialism, this foundation was the development of the productive forces. That theory has today been replaced by one more palatable to our contemporary sensibilities: the choices made by individual economic actors who seek to reproduce themselves. Chitty, aware that this takes us back to the most unreconstructed conception of the subject, hesitates in adopting this framework. Foucault made the point quite clearly in The Archaeology of Knowledge: