Ralf Hoffrogge

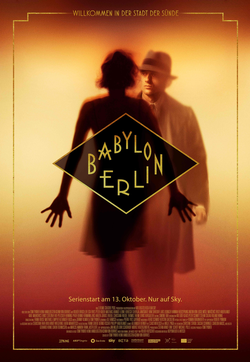

The German neo-noir television series Babylon Berlin, based loosely on the best-selling novels of Volker Kutscher, has spurred a wave of nostalgia for the1920s since Netflix aired the first season in 2018. In the latest season three, a young woman enters the scene: Marie Louise Seegers, daughter of the highest-ranking General of the German Reichswehr – and a devoted communist, ready to spy on her father’s secrets. The character looks so obviously made up that it has escaped most viewers that Marie Louise is based on a historical figure.

Berlin Babylon – Babylon Berlin

Unlike other pieces of German popular culture, Babylon Berlin does not shy away from politics: its main plotline is a military conspiracy by elite reactionaries in armed forces, police and politics that want to get rid of the young republic’s democratic system. The only discussion point seems to be whether those street-fighting Nazis can be of any help in this effort – or whether they are simply proletarian troublemakers. One of the main agents of the plot against democracy is General Seegers, head of the armed forces. Season three introduces his daughter Marie-Louise Seegers, who is shown as enthusiastic Marxist. The attractive and intelligent young women reluctantly gives in to the general’s request to entertain his friends on the piano – only to confront the reactionary clique with her critique of the capitalist system during dinner afterwards. Well-informed viewers have recognised quotes of Walter Benjamin in her replies. But not many identified the real woman serving as role model for the character: Marie Luise Baroness of Hammerstein-Equord (1908–1999).

Marie Luise was the daughter of General Kurt von Hammerstein and indeed a member of both the Communist Party and its secret intelligence apparatus. She and her sister Helga were involved in leaking crucial information about the Weimar Reichswehr. This started in 1929 and in 1933 they transferred intelligence about Hitler’s planned invasion of the Soviet Union to the Soviet authorities – years before the attack was carried out. The figure of Marie Luise, sometimes varied as “Marie Louise” or “Marieluise”, has captured the collective imagination of prominent German novelists such as Franz Jung, Alexander Kluge or Hans-Magnus Enzensberger – but with rather mixed results. Marie Luise, who died in 1999 in Berlin as a decorated anti-fascist veteran, is mostly portrayed as a naive student whose Marxist convictions did not derive from own reasoning, but from the seduction by an older man – Werner Scholem (1895–1940).

Scholem was a left-wing Communist, expelled from the German Communist Party due to his opposition to Stalin in 1926. He had indeed met Marie Luise when both studied law at Berlin University around 1927. So far, the novelists got it right – but, after that, imagination takes over, and it is as sad as it is telling how the roles are juxtaposed: while, in real life, Marie Luise was the driving agent and Scholem only got caught up in the case, in the realm of literature, Werner plays the active part and Marie Luise is reduced to his sidekick. But, where high culture has distorted historical reality, popular culture sets the record straight: In the series Babylon Berlin, there is no mention of Werner – only in one scene does Marie Luise mention a man, Oskar, mocking him an “unreliable subject”. This seems intentional, Marie Louise acts on her own. But why did her story go wrong in the first place? Based on my biography of Werner Scholem published with theHistorical Materialism book series,1 this article will help you to tell the difference between fiction and reality around the drama of Werner and Marie Luise.

Strong men and seduced women – Marie Louise in Literature

The first writer working with the espionage drama around Werner Scholem and Marie Luise von Hammerstein was Arkadij Maslow, a left Communist and close acquaintance of Werner Scholem.2 Exiled from Germany, Maslow conceived an entirely new life story for Scholem. Completed in 1935, his first and only novel was titled Die Tochter des Generals [‘The General’s Daughter’]3 and revolved around the exploits of ‘Gerhard Alkan’, an allusion to Scholem. Although the novel went unpublished for decades, Maslow’s manuscript circulated in literary circles and was revisited and adapted several times, making its author the originator of both Marie Luise and Werner’s duplications as a fictional character.

A university lecture by the boring ‘privy councillor’ Triepel at Berlin University’s law school in the year 1927 – this is how Maslow introduces his main female character, Marieluise von Bimmelburg, the ‘General’s Daughter’ – a malapropism of Marie Luise von Hammerstein. Whether Bimmel or Hammer, Marie proved to be much more than just another daughter of noble upbringing, both in the novel as well as in real life. Her father was the head of the so-called ‘Troop Office’, a covert name for the German general staff, and thus the highest-ranking military officer in the Weimar Republic. Ultimately, however, it is Marieluise who is taken in by the older man’s exciting life. The young woman is keen to break free from the constraints of her family background and virtually forces Alkan into an affair. Marieluise seeks to demonstrate that even an aristocrat can serve the revolution. Sometime in early 1933, the General’s daughter of Maslow’s tale, sneaks into her father’s study and steals a file – in the novel, a document without significance. Marieluise’s amateurish theft, however, brings Alkan and his lover into the Nazis’ sights, and thereby pulls Scholem’s Doppelgänger into a plot to oust the General – who, as a conservative, is not fully in line with the Nazis. Marieluise is subpoenaed, intimidated, and wilts under pressure. Unaware that she had only stolen planted, irrelevant documents, the young woman signs a confession. Alkan, aka Scholem, is arrested shortly afterwards and presented with a fabricated charge. While Alkan is caught in an unending limbo of indecision and uncertainty, his lover’s end is definitive: the General’s daughter is beheaded at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin.

The real Marie Luise von Hammerstein was spared decapitation. She would outlive Maslow by decades, dying in 1999 at the age of 91. In the novel, her fate is mixed with that of Renate von Natzmer, an employee at the Reich Ministry of Defence who was executed on charges of espionage in 1935. Maslow took even more liberty in devising his characters than he did with regard to his plot. In Maslow’s novel, Alkan and other characters created with this amalgamation technique vacillate between caricature and tragedy, supplemented with a pinch of Boudoir-esque eroticism. The latter is almost exclusively to the detriment of the main female characters throughout, whom Maslow models as naïve and seducible victims of their own desires. The actual Marie Luise von Hammerstein relinquished the privileges of her noble family background, risked her life for her beliefs and faced significant political persecution during the Nazi era. In the novel, she becomes the unremarkable Marieluise von Bimmelburg, whose political acts depend entirely on her current love affair. Maslow’s male characters, by contrast, appear as active protagonists, in spite of their general pettiness and malice. Neither Maslow nor his life partner, the former KPD-chairperson Ruth Fischer ever found a publisher for the novel. For decades, the manuscript gathered dust in an archive at Harvard University, before being published in an annotated German edition in 2011.

But, long before, through Maslow and Ruth Fischer, the motif was passed on to exiled writer Franz Jung. Fischer and Jung had known each other since 1919 and remained friends after Ruth Fischer distanced herself from Stalinist Communism. Jung, after all, was anything but a hack. He was expelled from the KPD as a left deviationist already in 1920. It was Fischer who introduced Jung to Maslow’s literary legacy after the latter’s death in 1941. Jung recognised the material’s potential and worked on a ‘radio novella’ from the mid-1950s onward, and later on a TV movie, but his impressive manuscript would ultimately fail to bear fruit. Jung died in Stuttgart in 1963, his manuscript ‘Re. the Hammersteins – The Fight for the Seizure of Command over the German Army 1932–7’, was only published posthumously in 1997.4 Jung’s narration is essentially a condensed and politicised version of Maslow’s novel. He reduces the private dramas and anecdotes, guided by the structure of classical drama, whose characters inescapably head towards catastrophe against their own better judgement. Furthermore, he refrained from using pseudonyms: his main characters were not Alkan and von Bimmelburg, but Scholem and von Hammerstein. In Jung’s account, there are similar attempts to compromise the General through his daughter’s Communist involvement. Werner Scholem appears not as a victim, but as a willing protagonist. His appearance is of fascinating ambivalence, combining dry rationalism with communist passion. Marie Luise, who Jung refers to only as ‘the daughter’, is impressed and seeks to get to know Scholem better, but is received coolly: ‘Scholem had already made an ironic joke of this. He talked about his family, wife and children, his understanding of family cohesion, his view on marital and extra-marital relationships, the overratedness of sexual intercourse, the glandular functions and secretions, all in a style resembling the interpretation of an article in a legal brief’. But, nevertheless, ‘the tragedy ensues and takes its course’. The two begin an affair, and Marie Luise once again forces documents from her father into Scholem’s hands, although, this time, the material is not irrelevant, but rather explosive: contingency plans for war with the Soviet Union. Marie Luise and Scholem are arrested and subjected to harsh intimidation. But, unlike in Maslow’s telling of the story, in Jung’s version, Marie Luise shows backbone and defends her lover vigorously without giving away any secrets. Scholem also remains stubbornly silent. The Gestapo is forced to pursue other strategies, Scholem grows useless to them and is soon taken to a concentration camp: filed under the ‘typical reference number’: ‘Return undesired’. What Maslow presents as a tragic comedy about human cowardice, Jung turns into a drama in which the harshness of reality overwhelms the individuals involved. Despite his private affairs, Jung’s Werner Scholem is a thoroughly political person, experienced and perceptive, yet also powerless vis-à-vis the conspiracies closing in on him. Marie Luise is part of the tragedy – with more moral backbone, but still second to Scholem, who is the main actor on the stage set by Jung.

Scholem’s and Marie Luise’s colourful literary phantasms free themselves from the biographical limitations even further in the work of a third author, the narrative Lebendigkeit von 1931 [‘Vitality of 1931’] by Alexander Kluge, published in 2003.5 This tale did not draw from Maslow’s novel, but directly from Franz Jung’s text, rounded out with observations from contemporary witness Renee Goddard, Scholem’s daughter. Kluge had managed to convince her to conduct a film interview with him. In Alexander Kluge’s story, Werner Scholem joins the KPD’s military-political apparatus in 1929: ‘His task is to subvert the army, to obtain illegal state secrets’. To Kluge, however, the matter at hand is more than just a spy thriller. Instead, the motif of a ‘secret life’ becomes a metaphor for the contradictions of the human psyche as such. Kluge hints at the dilemmas of biographical writing, which entails constantly searching for a ‘red thread’ to unite the narrative, despite the fact that real people never actually follow a single path in life. Therefore, Kluge takes even more liberties than Maslow, presenting Scholem as some kind of Communist version of James Bond, who tries to win over the proletarian rank and file of Hitler’s street fighting organisation SA to the Communist cause. Once again, Scholem is the master spy while Marie Luise is more or less a source for secrets Scholem wants to obtain.

A fourth and final author boils the matter down to an essence: Hans Magnus Enzensberger in his 2009 account, The Silences of Hammerstein.6 Ultimately, what emerged from his through collaboration with historian Reinhard Müller is a hybrid, a non-fiction novel which interprets history and fills in the gaps with anecdotes and fictional elements. Despite the great temporal distance that had since developed, Enzensberger’s version also bases itself on oral accounts, which he first encountered in 1955 during his time at the Süddeutscher Rundfunk:

One day there appeared in the Stuttgart office […] an elderly man, in poor health, from San Francisco, small and shabbily dressed but with a pugnacious temperament. At the time, Franz Jung was one of the forgotten men of this generation. […] The visitor made suggestions, and I still remember that Hammerstein and his daughters were also mentioned. I was fascinated by what Jung told us and scented an exemplary story. In my naivety, I also took everything I was told at face value and overlooked the cheap novel elements of Jung’s hints and suggestions.

That said, it took Enzensberger more than forty years to process the material and publish his own version. Here, Werner and Marie Luise again play prominent roles. Her classmate’s political background impresses the General’s daughter, and their liaison initially takes the path familiar from previous accounts. Her father was aware of the relationship, but ‘passed over [it] in silence’. In Enzensberger’s narration, Marie Luise fulfils KPD ‘party duties’ independently of Werner from 1930 onward – just like the real Marie Luise did, with the only inaccuracy that she started in 1929. The General, although increasingly suspicious, protects her from repression. This does not stop her from sending further documents to far off Moscow. In Enzensberger’s story, however, they are neither plans for a coup d’état nor trivialities, but rather confidential documents relating to German foreign policy. First, she smuggles out a transcript of Hitler’s inaugural speech to army generals on 3 February 1933, delivered after a formal banquet at Hammerstein’s official residence. This meeting did in fact occur, and was tremendously important to Hitler’s consolidation of power. His aim was to commit the leaders of the military to the new regime. Apart from Marie Luise, her sister Helga is also said to have overheard Hitler elaborate his agenda to the officials present. Hitler’s words have been recorded in various transcripts later published by historians. Hitler presented his vision of expanded Lebensraum in Eastern Europe, calling for Germanisation of conquered territories and the expulsion of native populations. The Führer was straightforward, promising rearmament and a new war. His adversaries soon had knowledge of the impending danger, for a transcript of Hitler’s remarks would reach the Comintern in Moscow only three days later. Enzensberger, like many historians asks himself: Who was behind this masterpiece of KPD intelligence? Had Marie Luise been the leak, and Scholem her contact?

Enzensberger, for his part, believes ‘this can with good reason be doubted’. Instead, he brings up Marie Luise’s sister Helga’s relationship with a Communist – Leo Roth, an agent of the KPD’s ‘N apparatus’ who intercepted all sorts of crucial information for the party. Roth is a historical figure, his biography exhibits parallels to that of Werner Scholem. Born in Russia but raised in Berlin, he joined the Left-Zionist group Poale Zion as a teenager before switching to the Communist youth organisation in 1926. Although Leo Roth, born in 1911, did not belong to the war generation, his youthful radicalisation very much resembled Werner’s. A supporter of Karl Korsch, Roth was driven out of the ranks of the KPD, joined the Lenin League and became involved with Ruth Fischer and Arkadi Maslow. But, unlike Scholem, Roth was not a leading member of this group, so he was re-admitted to the KPD in 1929 . Operating under the codename ‘Viktor’, he built a career in the party’s intelligence service, serving as a leading functionary by 1933 at the uncommonly young age of 22.

After having introduced Roth, Scholem’s connection to KPD espionage strikes Enzensberger as rather implausible. He declines to investigate the matter further, as Kurt von Hammerstein and his family are the main subjects of the story. Unlike Maslow in 1935, Enzensberger depicts von Hammerstein against the backdrop of World War and Holocaust, allowing him to appear as a possible alternative to the coming horror. The General almost appears as a resistance fighter, although Enzensberger cannot avoid reference to Hammerstein’s initially positive view of the Nazis. ‘We want to move more slowly. Aside from that, we’re really in agreement’, the historical Hammerstein is purported to have said to Hitler in 1931.

Nevertheless, Hammerstein did attempt to appeal directly to Hindenburg in the final days of January 1933 and prevent Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor. Hindenburg, however, ignored his advice, and Kurt von Hammerstein quietly resigned as chief of command in September 1933. Open resistance would come neither from him nor from any of the other generals over the next decade. It was not until the defeat at Stalingrad that a handful of officers dared to strike a blow against the Führer, whose uniform they had worn loyally for over a decade, in the summer of 1944. Two of von Hammerstein’s sons were among these ‘men of 20 July’. The General himself, however, was not: Kurt von Hammerstein died in the summer of 1943. Werner Scholem lived to see only the first year of this new war, detained in the Buchenwald concentration camp where he was murdered in 1940.

The Hammerstein Case: Fiction and Reality

In the universe of Babylon Berlin, the story ends in 1929 and only the next season, which is said to be staged in 1931, will show us how the story of Marie Louise Seegers unfolds. But what about the real Marie Luise – and Werner? A glimpse at Werner Scholem’s police and court files, now kept in the BerlinBundesarchiv, is actually rather sobering. One finds no mention whatsoever of Marie Luise or her father, nor of stolen military documents or secret telegrams to Moscow. Instead, the main points of concern are some remarks made during a quite trivial conversation over drinks at a bar. Some military men were indeed present, although they were not generals, but rather a horde of drunken infantrymen. Neither was Scholem ever charged with espionage. Rather, Werner supposedly attempted to ‘incite discontent among Reichswehr soldiers and provoke their insubordination towards their superiors’. Werner Scholem as subverter of German army discipline? The strange prose referred to an incident in early 1932 when Werner and his wife Emmy were said to have met with former KPD parliamentarian Wilhelm Koenen in a bar in Stromstraße 62 in Berlin’s Moabit district. The establishment was run by Paul Schlüter and called ‘Zum Bernhardiner’, named after the famous St Bernhard dog breed. Its patrons, however, fondly referred to it as the ‘Dirty Apron’. The indictment brought against Scholem recounts what allegedly conspired:

The three culprits mentioned sat at a table in the tavern together with four Reichswehr soldiers […] All three tried to convince the soldiers they ought to bring together the Communist-oriented soldiers in special cells so as to further infiltrate the Reichswehr. Furthermore, they insisted that the soldiers of the Reichswehr should not, under any circumstances, shoot at workers if they were to be deployed against them. During their conversation they passed newspapers and hand-written or hectographed leaflets titled “Reichswehr Soldiers – Comrades” to the soldiers.

The matter seems laughably trivial compared to its dramatic literary counterparts. Nonetheless, urging German soldiers not to fire on civilians in the case of an uprising did in fact constitute high treason. The corresponding law, dating from the Kaiserreich, remained in effect during the Weimar Republic and was attached to more severe punishments after 1933. The investigation was conducted by Section IA of the Berlin police – i.e. the political police of the Weimar Republic, not the Gestapo. Only a letter written by Werner’s mother Betty Scholem in May 1935 hints to the General’s daughter. She wrote:

The Hammerstein story goes something like this: Werner, in his profound cleverness, persuaded General von Hammerstein’s daughter to join the Communist Party. When they arrested her in April 1933, she of course changed sides and did her best to wash herself clean through accusation – more specifically, by claiming that Werner had seduced her (hopefully only to Communism!). I heard about this girl only once, when Werner bragged that an aristocrat had gone over to their side. He really is a jackass of historic proportions!

Betty received her information second-hand from Scholem’s wife Emmy, who had been arrested, but later was released due to her bad health. She fled to Britain in 1934 and was firmly convinced that Marie Luise had incriminated Werner. There is, however, no evidence for this in any of Scholem’s police and court files, nor does it seem particularly likely given that essentially any fellow student enrolled during the summer semester of 1927 at Berlin University could have observed and reported their contact. Neither is there any indication of espionage activities on Werner’s part anywhere in the Scholem’s testimony – Emmy denies them, Betty does not mention them at all, and no evidence can be found in the archives. After taking all available facts into account, a different story appears far more plausible: after 1926 Werner was alienated from the ‘Stalin Communists’, as he called them, but he remained faithful to the Communist idea, and it would have come naturally to him to discuss politics when meeting an interested young woman, demonstrating his extensive knowledge on the topic in the process. Marie Luise’s interest had been piqued by Werner’s knowledge and experience in political work; the intelligence services had little to do with their contact, to which Marie Luise von Hammerstein herself ultimately testified.

If one follows the court files, Werner was arrested not because of his connection to Marie Luise – he fell victim to a police informer called Willi Walter, who simply invented Scholem’s meeting with the soldiers at the “Dirty Apron” in 1932. The files reveal that Scholem’s wife was a regular there – it was the local hangout for communists in the Hansaviertel-neighbourhood where the Scholems lived. When communist and anti-militaristic graffiti popped up in the area, police started an investigation – and pressed local residents to identify potential agitators by showing them archived photographs. Among those were photographs of Werner shelved during former confrontations with the political police. Willi Walter, as a diligent informer, ultimately “identified” more than a dozen people. Werner therefore fell victim to his past – in 1932, as a prominent former Reichstag deputy, communist dissident and follower of Trotsky, it was impossible for him to work for Stalin’s intelligence service. Even the Nazi “Volksgerichtshof” in 1935 found this unlikely – Scholem was acquitted. But this was of no use for him: while other culprits walked free, Werner, as a communist of Jewish descent, was transferred to a concentration camp. He was murdered in Buchenwald in 1940.

But who leaked Hitler’s speech to Stalin? Was it Marie Luise then? Despite maintaining a steadfast public silence throughout her life, a government questionnaire from 1973 sheds more light on her involvement. The document in question is Marie Luise’s application to be recognised as a ‘Persecutee of the Nazi Regime’ under East German law. Here, Marie Luise admits, for the first time, that she worked as a member of the KPD’s intelligence service from 1929 onward. Her duties were strictly conspiratorial:

At the same time, I was instructed to cease all public party activities. Neither was I allowed to carry my party book with me any longer […] I was urged to mingle in my father’s social milieu. My task was to immediately pass on the content of any conversation I overheard. It was then forwarded to my closest colleague, Comrade Leo Roth. There were frequent meetings at brief intervals with him […] I also sought the aid of my sister who is five years younger than me […] My tasks furthermore included monitoring my father’s written correspondence. For this purpose I received a duplicate key to the desk in the private residence. Any letters of concern were then photocopied at night and returned immediately.

Enzensberger, who must have known this file via his co-writer Reinhard Müller, presented the accurate version: Leo Roth was the Hammerstein sister’s KPD go-between. In a letter intercepted by the East German Stasi in 1985, Marie Luise explicitly denied the notion that Werner Scholem recruited her: ‘I was already a Communist when I met Werner at university […] Through his wife, Emmy Scholem, I came into contact with the locally responsible neighbourhood group. There can be no question of my “recruitment” to the party by either Werner or Emmy Scholem’.

Werner and Emmy supplied contacts and perhaps even ideas to a young student whose political engagement was nevertheless self-motivated. Marie Luise had previously been active in the ‘unpolitical youth movement’, but was left unsatisfied with the generational rebellion and sought out socialist theory: ‘I found the answer in Marx and Engels’, she wrote in a 1964 article in the East German daily Neues Deutschland recounting her adolescent politicisation. Both Marx and Engels, as well as Werner Scholem had a certain influence on Marie Luise. Werner must have seen something of himself in her when they met in 1927: a young woman, alienated from her family, involved in the youth movement and in search of deeper meaning in life. She struggled with her transition to adulthood, hammered out her own worldview and searched for her path into a new society – in short, Marie Luise found herself at the same point in life in 1927 as Werner Scholem had in 1912, when he converted to socialism. The two travelled this path together for a brief period, full of enthusiasm and evidently somewhat in love with each other. But Werner’s cynicism vis-à-vis the Stalinised German Communist Party was anything but compatible with Marie Luise’s youthful optimism towards that party. Werner remained a renegade in the eyes of his former comrades, while Marie Luise quickly ascended into the inner circle of the KPD intelligence gathering service – without Werner’s protection. From then on, their lives would follow different paths, as not only Emmy, but also her daughter Edith Scholem confirms – she was born in 1918 and a teenager when her father was arrested. Edith states that Marie Luise was ordered by the KPD to end all contact with Werner, with which the young Communist complied. Marie-Luise survived fascism and war, working as a lawyer in East Berlin from 1952. In 1973, she was awarded the “Medal for Fighters Against Fascism” by the East German authorities.

Leo Roth had a more tragic fate. The Nazis were never able to trace him, and he managed to stay in Germany under a false name until being recalled to Moscow in 1935. Despite his service to the Soviet Union, he quickly became a target of Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD, who were suspicious of his contacts with foreign embassies and the Germany army, amplified by his links to Karl Korsch and other ‘renegades’. Roth’s name was placed on an NKVD list of ‘Trotskyites and other hostile elements’ even prior to the first show trials in Moscow. Arrested on 22 November 1936, Roth was sentenced to death on charges of ‘espionage’ by a military tribunal after a year of imprisonment, and executed by firing squad on 10 November 1937. He was 26 years old.

The intelligence Roth provided was ignored and left to collect dust in an archive. Stalin would conclude a pact with Hitler partitioning Eastern Europe in 1939, even though, thanks to Roth and the Hammerstein sisters, he knew of Hitler’s plans for conquest and extermination in the eastern territories first hand. Stalin’s characteristic paranoia when it came to imagined domestic threats found no equivalent in foreign policy, where the logic of the balance of forces had long superseded the revolutionary idea. That the Nazis might strike a different balance between reasons of state and ideological fervour seems not to have occurred to the Soviet leader.

Image By Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56738759

- 1. Ralf Hoffrogge, A Jewish Communist in Weimar Germany – the Life of Werner Scholem (1895–1940), Haymarket Press, Chicago 2018. This article is based on Chapter 7 of the book, all references and sources and an in-depth discussion of the case based on the juridical records can be found there. This article owes much to the work of Loren Balhorn and Jan-Peter Herrmann, who did a fantastic job in translating the German original of the Scholem biography into the English Language.

- 2. Mario Kessler, A Political Biography of Arkadij Maslow, 1891-1941: Dissident Against His Will, Cham 2020: Palgrave.

- 3. Arkadij Maslow, Die Tochter des Generals, Bebra: Berlin 2011 (original manuscript 1935).

- 4. Jung, Franz 1997, ‘Betr. Die Hammersteins – Der Kampf um die Eroberung der Befehlsgewalt im deutschen Heer 1932–1937’, in Franz Jung Werkausgabe, Vol. 9/2, Hamburg: Nautilus.

- 5. Kluge, Alexander 2003, ‘Lebendigkeit von 1931’, Die Lücke die der Teufel läßt, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, pp. 25–30.

- 6. Hans Magnus Enzensberger, The Silences of Hammerstein, Seagull Books, London 2009.