Articles

Frederick Douglass and Karl Marx on the Paris Commune and the Labour Question in the United States

Critical Theory without political praxis? A discussion with the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung

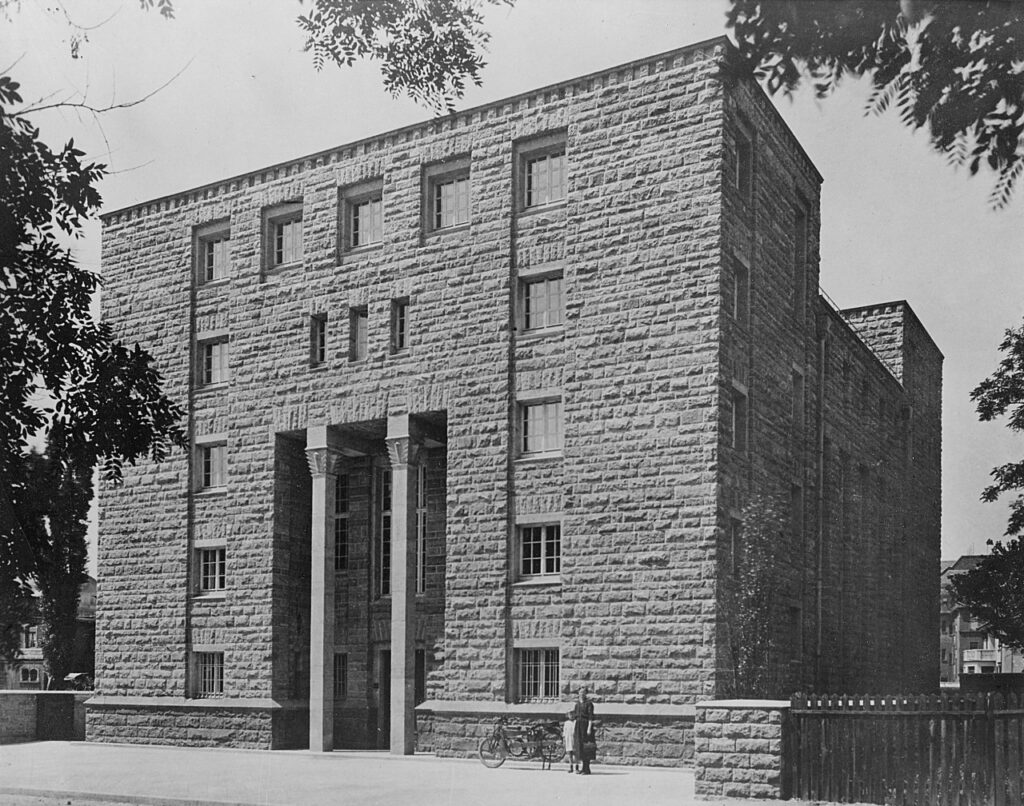

Edited by Max Horkheimer for the Institute for Social Research, the journal Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung stands in admirable contrast to the usual grey publications from the emigration-circles. From Thomas and Heinrich Mann to Brecht and Feuchtwanger, from Georg Bernhard to Hart and Hiller, from Stampfer to Walcher, Münzenberg and Pieck, those only reflect the general intellectual stagnation and decay. Apart from a small number of exceptions that we will discuss later, the contributions to this journal are on the contrary characterised by a high scientific level and purity in thought and words. Most of all, the essays by Horkheimer himself attract our interest. Horkheimer attempts to address the contemporary philosophical reaction – irrationalism, neo-empiricism, ‘neo-humanism’- with the tools of dialectical materialism, which he also calls critical theory.

John Bellamy Foster Interviewed by Daniel Tutt on Georg Lukács and The Destruction of Reason

In this interview, conducted on 10 February 2023, John Bellamy Foster speaks with Daniel Tutt about the work of István Mészáros and Paul Baran, contemporary irrationalist tendencies in left ecological thought, intensifying global class struggles and the continued relevance of Georg Lukács’s The Destruction of Reason (1952), recently reissued with an introduction by Enzo Traverso by Verso in 2021. The interview is being made available in advance of a forthcoming special issue of Historical Materialism, for which Tutt is a co-editor, dedicated to Lukács’s The Destruction of Reason.

I Am Afraid of AI

A Few Levels of Commentary

It was always about Marx and Freud: yesterday’s form, no doubt, of the age-old philosophical antinomy: mind/body, idealism/realism, base/superstructure, in a situation in which the opposition, the gap or break, reappears again within each term. The base has its own base/superstructure problem within itself, as does the mind: there is an interminable scaling at work, a fission, whose unimaginable end-terms are nothingness and infinity. (Even in Freud there is an obvious base and superstructure in the form of the Unconscious and its consciousness, while the latter is equally divided between itself and its unconscious ‘base’ in the super-ego.)

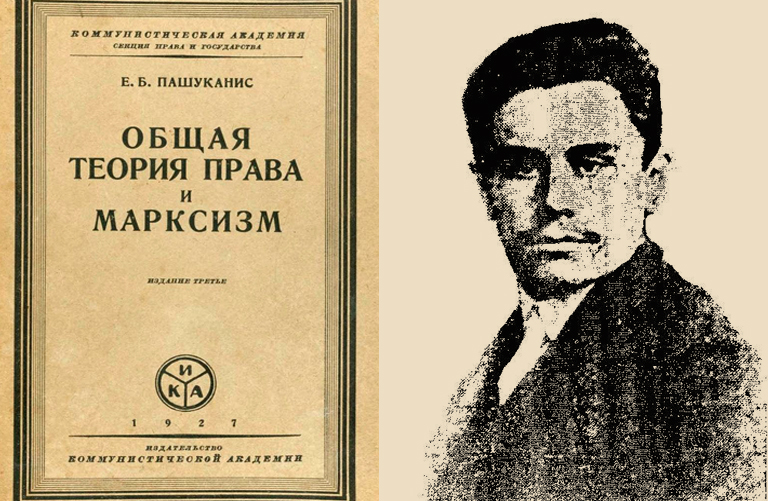

Three texts by Evgeny Pashukanis translated into English for the first time

‘Historical Materialism publishes three texts by Evgeny Pashukanis, translated into English for the first time.

“A Survey of the Literature on the General Theory of Law and State” (1923)

Jointly Edited and Translated by Rafael Khachaturian and Igor Shoikhedbrod.

“The Bourgeois State and the Problem of Sovereignty” (1925)

Jointly Edited and Translated by Rafael Khachaturian and Igor Shoikhedbrod.

Hegel. State and Law (On the Centenary of His Death)

Jointly edited and translated by Rafael Khachaturian and Igor Shoikhedbrod

Boris Kagarlitsky: In the Eye of the Storm

It takes enormous courage and principle to publicly oppose war by one’s own country. Think of the tiny group of Marxist internationalists who, en route to Zimmerwald in 1915 to denounce the imperialist war, joked they could be squeezed into four carriages. Dr Boris Kagarlitsky, the renowned, left-wing, Russian sociologist and political scientist, a vocal opponent of President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine since it was unleashed in February 2022, has now paid the price for doing so, twice: On 26 July 2023, Kagarlitsky was detained by the Russian federal security service, the FSB, charged with the alleged crime of ‘justifying terrorism’ based on an innocuous, jocular observation that he had made online back in October 2022, soon after the first Crimean Kerch Bridge explosion, that it could be understood ‘from a military perspective’; an absurd charge he vehemently denied. He was immediately transported from his hometown of Moscow to the remote northern city of Syktyvkar where he was detained awaiting trial and the prospect of up to seven years’ jail. In fact, on 12 December 2023, he was found guilty as charged by a military court, but, instead of jail, he was fined 609,000 roubles (6,337 Euro) and then released. Unfortunately, that was not the end of the now 65-year old’s tribulations. The prosecution appealed the fine as ‘unjust due to its excessive leniency,’ alleging that Kagarlitsky was bankrupt and that he had failed to cooperate with the court. This was a fabrication: While still insisting on his innocence, Kagarlitsky had paid the fine and cooperated with all the court’s requirements.[1] Nevertheless, on 13 February 2024, a military appeal court sentenced him to five years in a penal colony and banned him from administering any website for two years once his sentence is served. Immediately arrested, he has reportedly been detained in the Tver region neighbouring Moscow, although his precise whereabouts are undisclosed, standard Russian penal practice pending his appeal against the latest judgement which is scheduled for 5 June 2024.

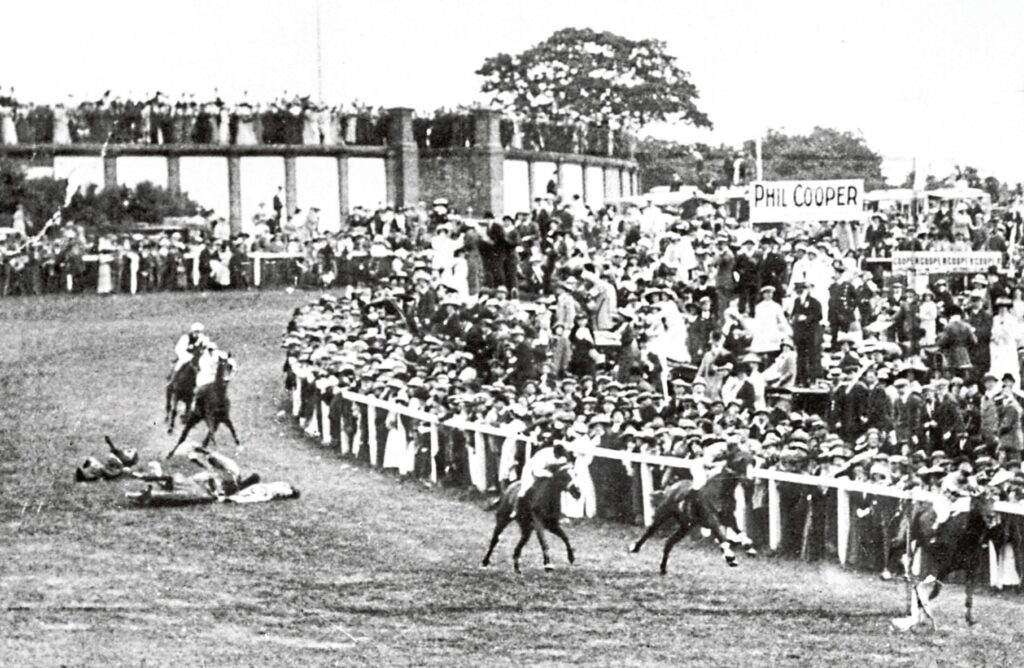

Forget the Pipelines: Blowing Up Bad History – the Peculiar Story of Andreas Malm and the Suffragettes

With its provocative title, Andreas Malm’s 2021 How to Blow Up a Pipeline broke out of the left ghetto and gained mainstream attention for the argument that the climate change crisis is so severe that direct action is justified. Certainly, we need more mass protest and campaigns to push for change. But Malm wants to go further, lauding disruptive direct-action tactics and suggesting that Extinction Rebellion is too tame.