Articles

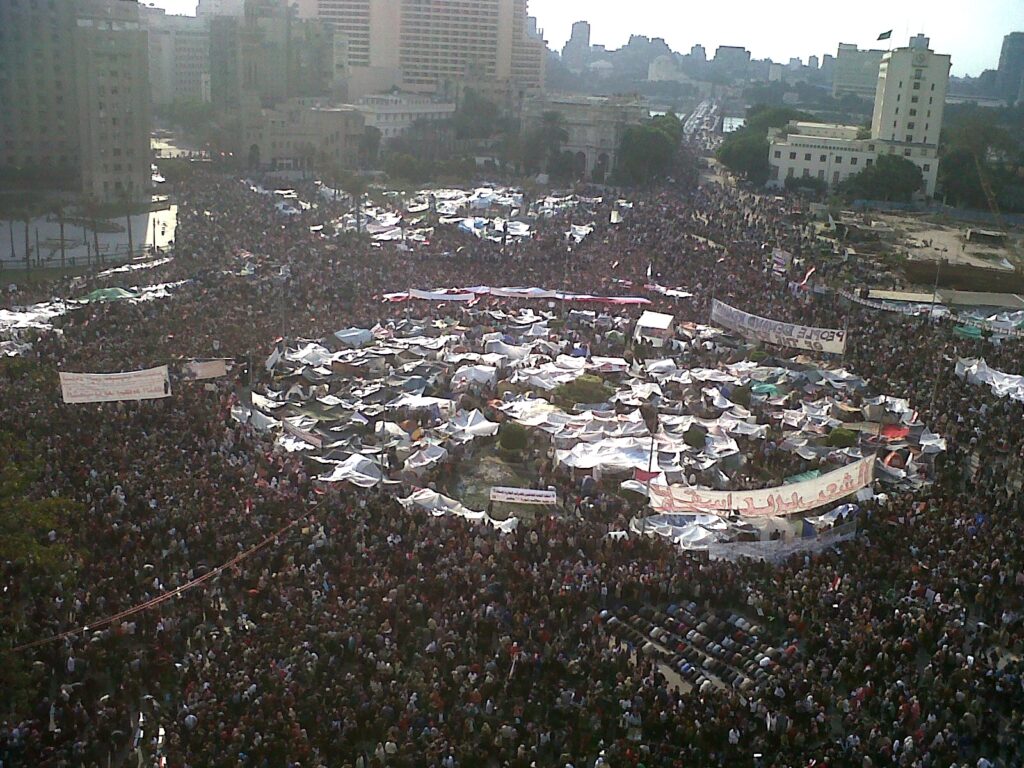

Can the People Overthrow the Regime While the State Remains in Place? On the Central Dilemma of the Arab Uprisings

The Elephant in the Room – the Rising Historical Standard of Living of the Working Class

The point is so elementary it ought not to require a quotation from Engels or anyone else to establish it. But, since the argument here points in a direction that many on the Left do not want to go, let us go with Engels. ‘The condition of the working class is the real basis and point of departure of all social movements at present … A knowledge of proletarian conditions is absolutely necessary to be able to provide solid ground for socialist theories …’. This is what he wrote in 1845 in his preface to his The Condition of the Working Class in England.[1]

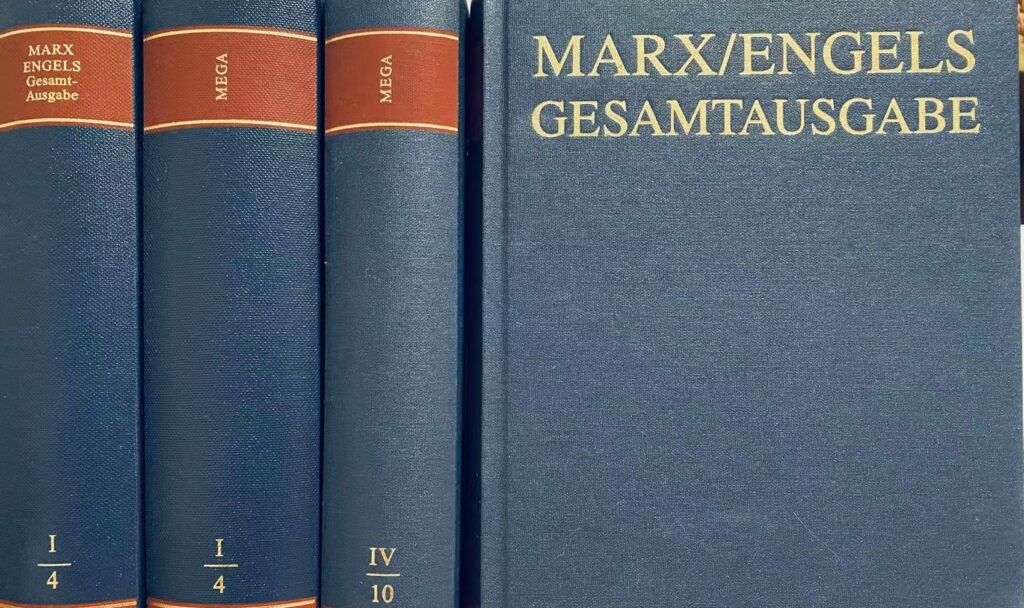

Introduction to Dossier ‘Marx, MEGA and MEGA-Marx’

Lenin once said: if you ditch Hegel, you derail Marx. This comes with a reminder: read your Marx or crash hard! But what to read in Marx, which Marx, when, and how? Reading Marx doubles, triples, quadruples as misreading, overreading, underreading, un-reading, Ur-reading Marx; as reading into Marx; as reading Marx into others; as reading Marx reading others. ‘Marx’ usually designates Marx and Engels as an intellectual unit and a political party; at other times, ‘Marx’ refers to a lone wolf apart from Engels. Engels, the ‘General’, for his part, inhabits several lives: Engels before Marx, alongside Marx shoulder-to-shoulder, and after Marx. Engels may have called himself a ‘second fiddle’ next to Marx, but he was more than a reader, editor and sponsor of Marx. He was a theoretician, tactician and adventurer in his own right. The two comrades in arms authored what fills their archives, and, by silence, what never made it in. Yet the fate of that legacy is scarcely theirs to decide alone.

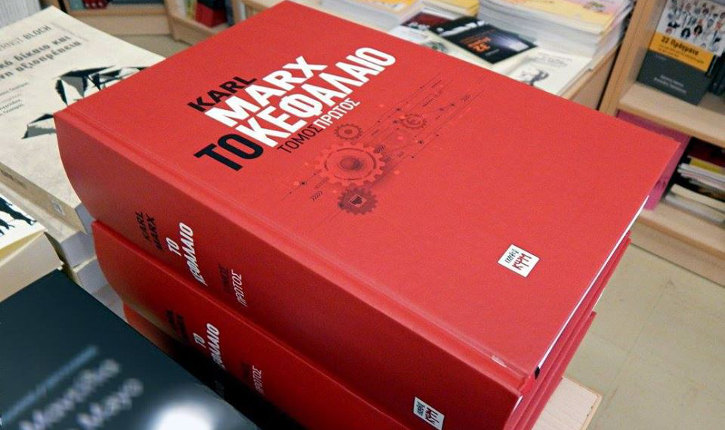

MEGA in Greece: Reflections on Translating and Editing Marx’s Writings

The reception and dissemination of Karl Marx’s opus in Greece, in its first steps during the interwar period, is combined with the development of the nascent labour movement. Already before WWII, there were more several attempts to translate Das Kapital, whereas many of the minor ‘canonical’ works (Manifesto of the Communist Party, On the Jewish Question, etc.) had been translated and published in the form of brochures (or newspaper articles) for the benefit of the militant classes. The militant aspect of the translations, i.e., their instrumental incorporation into the realm of political praxis in the form of an exemplary discursive reference,[1] was a feature that would accompany the translations of the majority of Marxian works in the following decades.

Reading Capital in Light of “New MEGA”: Teinosuke Ōtani’s Research on Marx’s Original Manuscripts and the Theory of Interest-Bearing Capital

In April 2019, the Japanese Marxist economist Teinosuke Ōtani[1] died at the age of 84. Outside of Japan, Ōtani is probably best known for his involvement in the Marx Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA) project. From 1992 until his death, Ōtani was a member of the editorial board of the Internationale Marx-Engels-Stiftung (IMES), which is tasked with editing new MEGA volumes; and, from 1998 to 2001, he headed the Tokyo-based MEGA editing team.[2]

A French edition of the works of Marx and Engels based on MEGA-2: the GEME project

The aim of this article is to present the main features of the Grande édition Marx et Engels (GEME)[1] project from a specific angle: that of the dissemination, in France and more generally in the French-speaking world, of the philological advances made possible by the second Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA-2).[2] The aim here is not to revisit the general theoretical issues[3] of the GEME project, but, rather, to situate it within the history of Marx and Engels editions in France in order to show the contribution made by the various volumes published since its launch in 2008 and to indicate how future volumes are likely to extend it.

Notes on the Translation of Some Specialist Marxist Terms into Italian and English

Adapted and translated by Gregor Benton and Ingrid Hanon

The Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe in Italy

The second Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe has enjoyed a degree of popularity in Italy since the late 1970s.

Trump 2.0, Fascism, and the Problem of Order under Capitalism

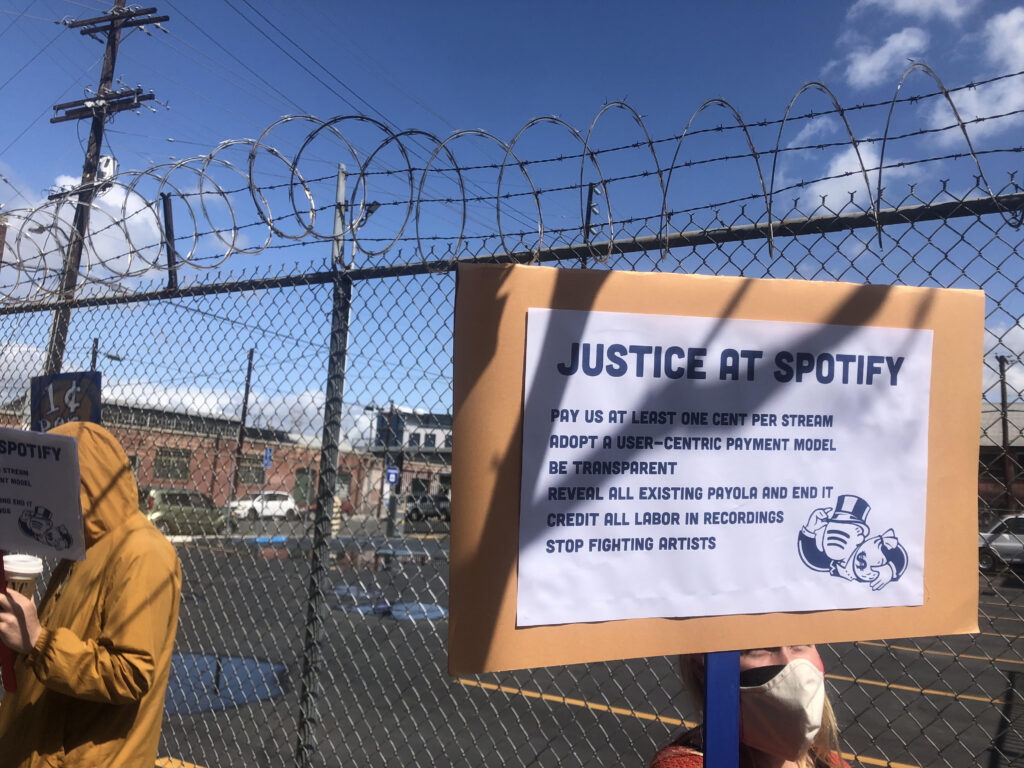

Every Song’s a War Song: Spotify and the Military Music Industrial Complex

In the 1890s, the idea of a “record industry” was a novel concept. The phonograph had only been invented in 1877, its close cousin the gramophone patented and made available for purchase little more than a decade later. The notion that you could hear a sound at a time other than when it was being created? Until recently, this had been beyond the pale of possibility, akin to the first decades of the photograph, just starting to shift the sonic and cultural contours of daily life.

The Council System in Germany (1921)

Richard Müller (1880–1943) was a German lathe operator, union organiser, and revolutionary who led the Revolutionary Shop Stewards during World War I. In November 1918, he became Chairman of the Executive Council of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils, effectively serving as head of state of the short-lived Socialist Republic of Germany. After losing influence in the Communist Party by 1921, he turned to writing, producing the classic three-volume history Vom Kaiserreich zur Republik (1924–25). Withdrawing from politics after 1925, he became a businessman and died in relative obscurity. For further discussion of Müller’s life and work, see the book by Ralf Hoffrogge, Working-Class Politics in the German Revolution: Richard Müller, the Revolutionary Shop Stewards and the Origins of the Council Movement.

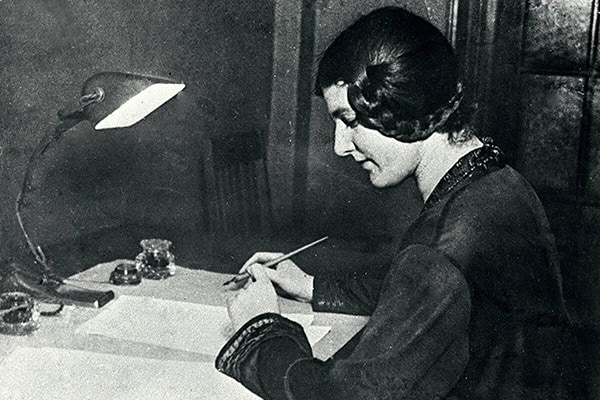

Who Was Larisa Reisner? An Interview with Cathy Porter

Cathy Porter, author and translator, educated at London’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies and Cambridge University, has published over twenty books on Russian history, culture and politics, most recently Larisa Reisner. A Biography (2nd ed., Brill/Historical Materialism/Haymarket, 2022), shortlisted for the Isaac Deutscher Memorial Prize, and its accompanying volume Writings of Larisa Reisner, her six books, translated with Richard Chappell, again for the Historical Materialism Book Series. Author of Alexandra Kollontai. A Biography, first published in 1978, she is also a translator of Kollontai’s fictional trilogies Love of Worker Bees and A Great Love. This interview was originally published in About Narration (1975): Materials, Comments, Interventions, Edited and introduced by Sezgin Boynik and Tom Holert, Rab-Rab Press, 2025