Anti-imperialism has a history that has been in large part repressed, if not buried, amongst many currents of criticial thought and much of the radical Left. The struggles for decolonisation after the Second World War are, of course, remembered, but, too often, it is forgotten that the international communist movement created anti-colonial and anti-imperialist organisations on a transnational scale. Such was the case of the League Against Imperialism. In this interview by Selim Nadi, first published in French in the online journal Périodehttp://revueperiode.net/willi-munzenberg-la-ligue-contre-limperialisme-et-le-comintern-entretien-avec-fredrik-petersson/, Fredrik Petersson discusses the foundation of the LAI by the Comintern. He depicts a colonial question that was resolutely understood as a transversal question by communists. He highlights also the necessity for a mediation between the headquarters of world communism (Moscow) and the nationalist forces in each country that were its allies, all of which is helpful in developing the concept, which is still neglected, of the ‘anti-imperialist united front’.

In your academic work, you are mainly interested in the League Against Imperialism (LAI) – founded in 1928 in Brussels. Why focus on anti-imperialism during the inter-war period (and not only during the decolonisation process after World War II)?

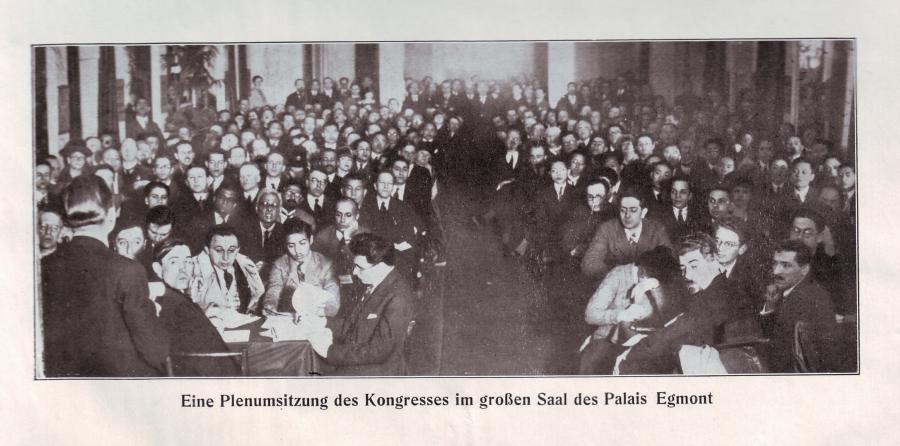

First of all, the founding congress of the League against Imperialism took place 10-14 February 1927. Now, with that sorted out, yes, one of my central items of research has been on the history and transnational networks of the LAI. I did my doctoral thesis on the LAI from the perspective that wanted to examine the twofold purpose: first, why the LAI was established in 1927; and second, the internal aspect of the organisation, something that required doing extensive empirical research in several archives in Moscow, Berlin, Amsterdam, London, and Stockholm, if I wanted to put the pieces together in a proper way. However, and after I got the thesis published the same year in 2013 as two volumes, I think the question of interwar anti-imperialism involves so many aspects that tells us about how the world was reconstituted after the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919. It is commonly accepted that the world was decolonised after the Second World War, yet my argument is that, in order for us to understand how this even was possible, we have to take into consideration the development of anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements as politically conscious entities between the wars. It was in the purest sense a time of learning, a time of accumulating experiences, and a time of creating relations and connections that either lasted or changed in the interwar years. Hence, it is about reading the history of decolonisation backwards, dating from, for example the “Afro-Asian conference” in Bandung 1955, and of connecting it to an organisation such as the LAI.

30 years after the founding of the LAI, during the Bandung Conference (1955), Sukarno said that if the founding congress of the LAI was held in Belgium in was not “by choice, but by necessity”, could you please explain this point?

Well, this is kind of a political statement on behalf of Achmed Sukarno where he more or less defined the historical progression of twentieth century anti-colonialism, and how the movement both relied on and was dependent on establishing connections and relations. But what Sukarno even more wanted to show with his observation was probably the following: in the interwar period, it was next-to-impossible to convene a similar congress or conference as the one held in Bandung 1955. Thus, by holding the “First International Congress against Colonialism and Imperialism” in Brussels, it was not only held there “by necessity”, but it was intended to function as a demonstration against colonialism and imperialism in one of the “hearts of imperialism”, and it could also gain attention amongst colonial emigrants living in Western Europe. However, what comes across as rather evident by reading the sources is that the formal organisers of the congress (the LAI’s forerunner: the League against Colonial Oppression, established in Berlin 10 February 1926) and its secretary, the Hungarian communist Laszlo Dobos, had promised the Foreign Secretary in Belgium, the well-renowned socialist Emile Vandervelde, that under no circumstances was the congress to deliver any critique of Belgian colonialism and the atrocities taking place in Congo. Even more, Dobos had to provide Vandervelde with extensive list of names of individuals planning to attend the congress. Hence, this pretty much outlines the historical experience of the Brussels Congress of not having been “by choice, but by necessity” as Sukarno later stated in his opening address.

Could you develop the main differences between the founding Congress of the LAI in Brussels in 1928, and the Baku Congress (1920)?

The central difference is how it was organised and under what kind of auspices and with what intentions. If we think about the Baku congress in 1920, it had been preceded by intense discussions between Lenin and the Indian nationalist revolutionary Manabendra Nath Roy on the colonial question at the Second International Comintern Congress in Moscow. Even more, the Baku congress was held for the primary reason of getting Far Eastern anti-colonial activists to support the recently established Bolshevik regime in Soviet Russia, or as the then Comintern chairman, the Russian communist Grigori Zinoviev, explained it: it was to win them fully over to communism. However, there is another dimension to the Baku congress, and it is that it offered Asian activists with an opportunity to meet and discuss with each other the situations in their home countries. While some, so to speak, drifted towards communism as a source that would support their struggle, other continued to forge the nationalist struggle along other principles shaped by socialism and liberalism. Thus, if we can compare Baku with Brussels, the later essentially continued the agenda of the former by highlighting how colonialism and imperialism continued to shape the world after 1919. One important difference between these two events was the more international scope of the Brussels congress, meaning, while Baku focused primarily on Asia and the Far East, the Brussels congress had an international outlook that tried to depict a global system of colonialism and imperialism. What unites the two of them is that they were both organised and sanctioned by the Communist International and its headquarters in Moscow.

To what extent was the LAI a response to Woodrow Wilson’s principle of national self-determination?

I think this is a central question that pretty much outlines and explains how the LAI came into fruition, at least, in the initial phase of 1927. As Woodrow Wilson introduced the famous Fourteen Points in January 1918, which included the relevance and importance of paying attention to the principle of national self-determination, in fact, this was replaced by the liberal internationalism on display at Versailles, and as consequence of this, this somewhat downgraded the capacity of the colonial world to become independent once the war was over. If we look again at the Brussels congress, its official credo and public slogan was to advocate “National Freedom – Social Equality”, and a majority of the speeches delivered at the congress addressed the call for national independence and the right to self-determination. In general, the propaganda of the LAI frequently called for a critical scrutiny of the fallacy of the League of Nations of putting into practice what it once had set out to do, that is, the equal treatment of all peoples and races through the principle of national self-determination. I think this was one of most potent and viable political messages of the LAI, and therefore, it can be seen as adversary and subversive contingent to the League of Nations.

Who was Willy Münzenberg (1889 – 1940)? What role did he play in the LAI?

Willi Münzenberg was pivotal for the LAI. Being a German communist and member of the German Reichstag, Münzenberg has been recognised as the leading entrepreneurial force in the development of communist propaganda in Europe and beyond between the wars. What has to be emphasised is that Münzenberg came from a pacifist and socialist background; however, after meeting Lenin in Zimmerwald in 1915, this was the beginning of his journey to communism. After having been an organisational force in coordinating the work among socialist and communist youth during the Great War, in 1919, Münzenberg was central in the establishment of the Youth Communist International (KIM). Later in 1921, Lenin appointed Münzenberg to establish the embryo of International Workers’ Aid, an international proletarian mass organisation that lasted until 1935 when it was quietly dissolved on the direct instructions of Comintern headquarters in Moscow. While this is a general description of Münzenberg’s political career, I consider Arthur Koestler’s foreword in Babette Gross book Willi Münzenberg. A politische Biographie (1967) still as one of the most accurate descriptions of the man: he was “a political realist” that should be seen as a propagandist and activist, neither as a politician nor theoretician. Then we have his so-called mysterious death in 1940, where his body was found in the outskirts of the French town Montaigne. There has been debate as to whether it was suicide or murder that caused Münzenberg’s death. Yet this discussion will continue without any real or credible empirical evidence. If we return then to his pivotal role in the establishment of the LAI, by this I mean that, without his energy and vision to organise “an international congress against colonialism and imperialism”, as he declared in a personal letter to Zinoviev in August 1925, there would not have been a project of trying to mobilise the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movement in Europe and the USA like that of the LAI. Second – and I keep returning to the Brussels congress, but still, it represents a central moment for interwar anti-colonialism – it was an idea that Münzenberg developed after being introduced to it by a couple of Chinese trade unionists in Berlin in connection with the “Hands off China” campaign in 1925. Yet what Münzenberg managed to do was to transform the idea into something viable and concrete. This did not, however, come without a price tag. Münzenberg had to either negotiate or rely on the consent of the Comintern before being able to proceed with the political project of the Brussels congress. And, indeed, the idea of establishing the LAI was not Münzenberg’s; it was on the recommendation of Manabendra Nath Roy in 1926. However, without the success of the Brussels congress, there would have never been any need for the establishment of the LAI. But both Münzenberg and the Comintern seemed unprepared as to how to approach and build on the success of the Brussels congress, which in the longer perspective implied that the idea of the LAI and its practical outcome started from the wrong foot from the beginning. Actually, together with some colleagues, I ma planning to write a personal biography of Münzenberg, with emphasis not on his political persona but rather trying to going beyond this perspective, and instead, try to discuss Münzenberg as a person and how different spatialities, opportunities and moments shaped his life. I mean, he still continues to haunt me in a funny way, and you just have to take into account the traces the man has left in numerous archives across the world. The story of Münzenberg has for sure not been fully told yet, I argue.

In your forthcoming book in the Historical Materialism Book Series, you write that the Brussels Congress and, later, the establishment of the LAI, had been the results of meticulous planning and construction rather than “by necessity”, in a “cleverly-disguised interplay between Münzenberg, the IAH [Internationale Arbeiterhilfe] and the Comintern”. Could you please develop the role played by the IAH and by the Comintern? What were the relations between the LAI and the Comintern?

Yes, that is correct; I am working on my book at the moment, which will focus more on the transnational character of the LAI, but also, the transnationalism of anti-colonialism between the wars. This November, I will return to Moscow and do additional research in the Russian State Archive for Social and Political History, which houses the papers of the Communist International. And this leads me again to the intertwined relationship between the LAI and the Comintern, or to be more precise, the constant and regular contacts that flowed between the LAI’s international headquarters in Berlin – the International Secretariat – and Comintern headquarters in Moscow. I mean, from the very onset, and even prior to the establishment of the LAI in 1927, various institutions and individuals at Comintern headquarters stipulated during the preparations for the Brussels congress in 1926, that the sole reason for establishing an international organisation against colonialism and imperialism was “to act as an intermediary between the Comintern and nationalist organisations in the colonies”. Further, the LAI’s International Secretariat in Berlin functioned as a hub for the organisation, meaning that it received instructions from Comintern headquarters, which in return were dispatched to the LAI’s national sections or affiliated members. In return, when the International Secretariat received information or intelligence from the sections, it was dutifully dispatched back to Moscow. In conclusion, every important decision pertaining to budget or personnel questions was taken in Moscow. This also involved the writing of political material such as congress resolutions, manifestos, pamphlets or material for the official publications of the LAI.

What where the kind of contacts the LAI had with European radical left movements?

In 1927, the contacts were strong and many. However, this depends on how you define “radical left movements” in Europe”. If we exclude the communist aspect here, I would say that contacts with radical trade unions, pacifist circles, socialists or anarchists were large from a quantitative perspective. However, once talk of the LAI as a new actor on the political stage began to emerge in 1927, and particularly as the organisation raised the question of being an ardent opponent against colonialism and imperialism, various circles in the European socialist movement approached the LAI with suspicion. For example, the leader of the Labour and Socialist International, the Swiss socialist Friedrich Adler, instigated a thorough investigation on the historical and political ties of the LAI, which in October 1927, drew the conclusion that the LAI had intimate ties to the Comintern and the international communist movement. As a consequence of this, any party affiliated to the Labour and Socialist International was prohibited of becoming member to the LAI. In a longer-term perspective, the communist connotations of the LAI severely restricted access to radical leftist movements that were not communist in nature and scope. What I am really talking about here is a kind of historical narrative that began with success but ended in seclusion and isolation the longer we stretch out the history of the LAI.

Did the LAI lead to any theoretical innovations concerning colonialism and/or racism?

No, I do not believe that. Yet what the LAI amounted to do was to function as nostalgic point of reference for the decolonisation movements that emerged in the postwar period. I have stated that the LAI should be seen as “a concerted source of inspiration” in the context of postwar decolonisation of the world, something that reached its culmination at the “Afro-Asian Conference” in Bandung in 1955. Moreover, what the LAI accomplished to do was in raising awareness in the so-called “imperialist centres” on the situation in the colonies. This was done through various campaigns, letter writing campaigns and so forth. Hence, what we are addressing here is the transnational scope of anti-colonialism between the wars, and how this was further developed after the Second World War in the postwar period.

In an article published in 1960 in Les Temps Modernes on Sultan Galiev, Maxime Rodinson wrote that the “Afro-Asian bloc” that followed the Bandung Conference was a kind of “Colonial International”, would you agree with this?

No, I would not agree with that. I think that you should rather see the LAI as an effort that tried to coordinate a range of nationalist organisations and movements that all were seeking to highlight their own political and cultural agenda. In fact, the Comintern feared the idea of the LAI becoming an anti-imperialist “International” capable of standing on its own. It was all about control over an agenda and political idea that had managed to create a buzz, and therefore, once the LAI was dissolved in 1937, several individuals that previously had held some role in the organisation, for example the British socialist and pacifist Reginald Orlando Bridgeman (who acted as International Secretary of the LAI from 1933 to 1937), quickly acted and formed new anti-colonial organisations or associations. In Bridgeman’s case, he formed the “Colonial Information Bureau” in 1937, which cooperated closely with the British “Centre against Imperialism”, where the former should be seen as more “socialist” while the later was “communist”. Hence, we are talking of transformations and transferences of ideas and practices here.

How would you describe the legacy of the LAI?

I think I have summed up that answer already, however, I would like to add that the LAI introduced a new form of activism in a world that had faced the horrors of global war (the Great War, 1914-18), and it aided in making anti-colonialism into a politically conscious movement from the perspective that it provided with contacts, relations and networks for anti-colonial activists that travelled the world between the wars. Later, a person such as India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who had been active in the first years of the LAI, could draw on this experience. In conclusion, I think that the LAI broke new political ground for anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism, however, due to the intimate relation to the Comintern and how the organisation developed itself in the 1930s, much of its history was seen as a failure, and therefore reduced to the dustbin of history. Yet, and which I hoped to do with my research, is in showing that there exists so many dynamic perspectives and relations that up until now have been forgotten and hidden.

Fredrik Petersson is Lecturer in General History at Åbo Akademi University since 2014. He received his PhD from Åbo Akademi University in 2013; his dissertation was titled‘We Are Neither Visionaries Nor Utopian Dreamers’. Willi Münzenberg, the League Against Imperialism, and the Comintern, 1925-1933 (published as vol. I-II, Lewiston: Queenston Press, 2013). Petersson is currently working on two projects: “The Elephant and the Porcelain Shop”. Transnational Anti-Colonialism and the League against Imperialism, 1927 – 1937 (forthcoming 2017) ; and the research project “Hidden Narratives and Forgotten Stories. The Colonial World in the Nordic World”. He has published several articles on anti-imperialism, international communism and radicalism.