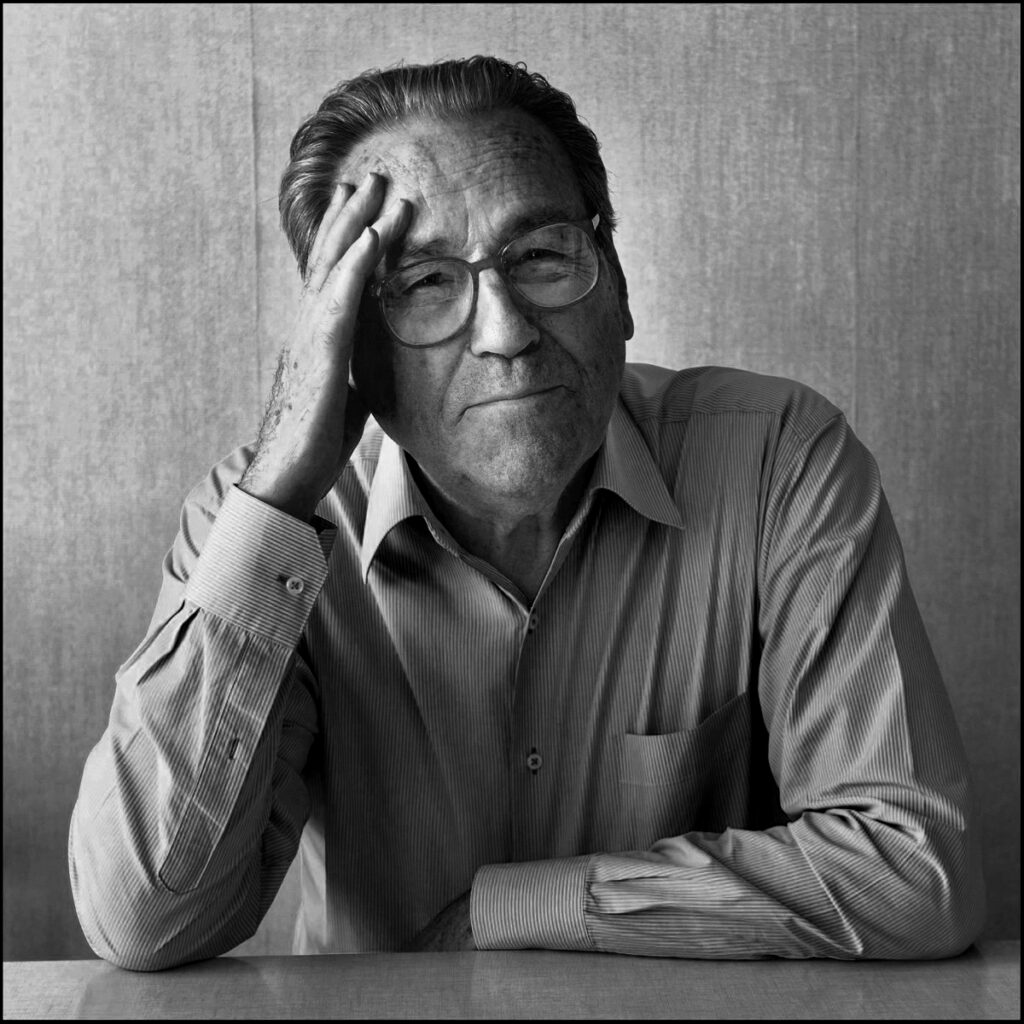

The philosopher and communist militant Lucien Sève died, aged 93, on the 23rd of March 2020. Lucien had been a close friend for over thirty years. The experience of reading his books, and then of our regular meetings, played a decisive role in my life. Regardless of whether we agreed or disagreed on a question, he was always a kindly and uncompromising interlocutor, unceasingly generous, brilliant and funny – a man of exceptional humanity. This text, written in sadness and anger, has no other ambition than to be a homage and an invitation to read or reread his – insufficiently known and discussed – work.

‘What if the most direct threat now was that of anthropological disintegration through the totalitarianism of the profit motive – what if the threat was no longer about the physical destruction of the species, but the moral asphyxiation of the human race?’[1] Those words now take on an ominous meaning: Lucien Sève, their author, died from COVID-19 on March 23, 2020, several days after going into hospital. Aged 93, he was categorised a ‘non-priority’ patient, deprived, because of the shortage of ventilators, of access to one. The disastrous state of French public hospitals, subjected for decades to destructive neoliberal reforms, in addition to a health policy that is nothing short of criminal, forced doctors to pick and choose between patients. Negligent at one moment, cynical at the next, the Macron government has given new life to social Darwinism, the pseudo-scientific name for capitalist barbarism.

This is, in fact, exactly the kind of fraudulent ‘Darwinism’ to which the CEO of the CNRS [the French National Centre for Scientific Research] – a revealing oxymoron – had the temerity to lay claim. In doing so, he played his part in despoiling French academic research all the more effectively – including, in particular, fundamental epidemiological research on the family of coronaviruses, conducted by precarious and under-funded teams.[2] If we add in the fact that the virus’ global spread does actually seem to have been caused by the advanced state of destruction of the world’s ecosystems, and accelerated by pollution from microparticles, then both the pandemic and its handling under liberalism are what Lucien Sève fought against his whole life long. They are also what finally put to an end to his life, though certainly not to his struggle – one which, more than ever, is our own as well.

Philosopher of the human person, thinker of bioethics, communist theorist and militant, Sève wrote in the following terms on the subject of the connections between health, ethics and funding:

Today, this kind of inversion of ends and means has embarked on a deep remodelling of the entire, painstakingly constructed system that was originally based on values of public responsibility, social solidarity and the dignity of the person. For this it intends to substitute, always in the name of efficiency, equality and liberty, commercial and financial regulations in which the qualitative differences between health and a product, or between the human body and a commodity, threaten, in the worst case, to vanish.[3]

Capitalism, which has now entered into the most destructive phase of its history, piloted by fanatical and authoritarian ruling classes indifferent to the lot of mankind or the planet, their eyes glued on dividends alone, is the deadliest of pandemics. Lucien Sève takes his place in the long tradition of those who have made the effort to link a continually renewed understanding of its logic with the struggle for its overcoming/abolition, as Marx said in a single word: Aufhebung.

Without making any claim to sum up Lucien Sève’s work and life here, we will follow a particular guiding thread – the theme of the human person and individuality as they wrestle with alienation. The first reason for this choice is that this theme runs through, and also crystallizes, the entirety of Sève’s trajectory, straddling two centuries and the multiple dimensions of his imposing œuvre. From his battle against the so-called theory of talents, in a widely remarked article of 1964,[4] to the question of the personality, and from bioethics to the definition of a new-generation communism, this question remains central. The second reason for choosing this thread is that, at the same time, it was continually woven into the concrete person of Lucien Sève himself – someone who, as is shown by the numerous biographical inserts in his books, was fond of reflecting on his own trajectory. In short, the Sèvian question of individuality, linking the private with the social, is the site of a relentless attempt to construct a unity between the thinker and their thought, in a tangible version of the marriage – permanently hoped for but permanently deferred – of theory and practice, the favourite slogan of an often hollow Marxism.

In fact, the question of the individual and of the social and political conditions of their emancipation appears very early in Sève. He was initially a Sartrean, before rallying behind the cause of Marxism and joining the Communist Party in 1950, in the very midst of the Cold War. This kind of intellectual and political itinerary, which led early on to Marx and to the PCF, was not a rare one for his generation. But in Sève’s case it was full of pitfalls – something that was rare for a graduate of the École Normale Supérieure and for a young holder of theagrégation degree in philosophy, who theoretically was destined to a peaceful career.

This career began with a dismissal from the French lycée in Brussels for having mentioned Lenin in positive terms at a lecture at the French embassy: it would certainly have been hard to shoot oneself in the foot more flamboyantly. A disciplinary transfer ensued: this time, Sève found himself threatened with permanent dismissal. He only escaped by putting an end to the deferral of his military service, and found himself assigned in 1952 to the ‘Bat d’Af’ [Bataillon d’Afrique, African Battalion], a disciplinary unit based in Batna in Algeria,[5] where bullying and threats intensified against the ‘communist militant for life’ that he was in the process of becoming.[6]

This trajectory, both intellectual and militant from the outset, excluded him from any university career. This was an enduring source of bitterness to Sève, even if, no doubt, it also protected him from any trace of scholasticism. Instead of the institution of the university, he had to grapple with a different institutional structure: the Communist Party. He quickly took on important roles in it, initially in addition to his teaching job in lycées, then as a full-time staffer. He was involved in training, and was a municipal councillor and also a union activist, as well as a member of France-USSR and of the Maurice Audin committee against torture in Algeria. From 1964 to 1994 he was a member of the Central Committee and from 1976 to 1982 director of Éditions Sociales [the official PCF publisher]. It was as the head of Éditions Sociales that he went about launching a complete – and for the first time rigorous – edition of the works of Marx and Engels in French.[7] From 1983 to 2000, he was a member of the National Consultative Committee on Ethics.

But Sève’s life cannot be reduced to these official functions and positions, since he gradually came to question the direction of the party leadership, and then to contest it: from 1984, he launched the idea of a ‘communist refoundation’, a critical current bringing together a group of communist leaders and intellectuals. He accompanied this, in himself, by an intense theoretical effort centred on communism as an abiding goal and on an ever more radical critique of the party form.

Lucien Sève was never a self-satisfied hierarch or a pontificating intellectual, any more than he was a rebellious maverick. In his last published book, the first section of the final part IV of his enormous compendium Thinking with Marx Today, which he began in 2004, he said that he had, for the first twenty years of his life as a militant, been a ‘conformist for the most part towards a party leadership which I thought seemed much more learned and experienced than me’, before, little by little, finding the courage to ‘think strategically by myself’.[8]

In their entirety, his career and his published work are shot through – but also structured – by the contradictions arising from a life of leadership roles in a Communist Party that was itself grappling with its past and present. Sève reflected on these contradictions continually. It should be recalled, contrary to all the hasty labels that exasperated him – ‘Stalinist intellectual’ or ‘official philosopher’ – that he was one of the principal agents of the de-Stalinisation of the PCF, a process he considered unfinished. He was also a fierce enemy of all dogmatic Marxism – he preferred to call himself a ‘Marxian’ – but also battled – with passion, partisan loyalty and sometimes sectarianism – against orientations he judged to be questionable. In 1980, he would self-critically revisit his 1960 polemic with Henri Lefebvre, recognizing that ‘the process of ‘philosophical justification’ of an exclusion from the party, which in my eyes appeared to be a fine Politzerian polemic, today seems to me to be unjustifiable’.[9]

How could anyone endure that kind of tension? By making it the very heart of a Marxism that was simultaneously engaged and committed to preserving its own ‘relative autonomy’, to repeat Engels’ famous enigmatic formula. A positioning of this kind is unstable by definition. All engaged Marxists who remain creative can be considered to be affected, in different ways and degrees, by the difficulties inherent in it, from the very moment they accept the link between theoretical work and militant intervention – a link that is tight, but that exists without either the fusion or confusion of the two.

In the face of the contempt and everyday prejudice that heterodox trajectories of this kind arouse, it is important to emphasize that the most pure academic careers are also situated in powerful institutional logics, most often without thematising or questioning their effects. That is why, contrary to all the reductive analyses denouncing partisan engagement as a simple intellectual straightjacket or as a cynical will to power,[10] a nuanced and detailed analysis of twentieth and twenty-first century French Marxism is yet to be produced – an analysis with the goal of understanding this difficult and stimulating articulation of theoretical work and political engagement, from Lucien Sève to Louis Althusser, from Henri Lefebvre to Daniel Bensaïd (to cite only them), which would challenge the thesis of a Western Marxism confined in theory.[11] At the outset of the unprecedented period that is opening today, faced with the combined rise of threats and possibilities, and in the face of the historic weakness of the organised workers’ movement, it is high time to extend and renew its heritage, remote from academic Marxologies and disenchanted post-Marxisms.

For his part, Lucien Sève always very consciously remained on the precipitous path of what could be called a ‘political Marxism’ – one concerned with global issues, but also involved in debates of the most tactical nature. For that very reason, his kind of Marxism needed continually to redefine and recapture the enabling conditions for an autonomy that holds a position of neither rupture with politics nor of mere observation of it from above the fray. These kinds of contradiction which – let us emphasise again – Sève experienced intimately, gave rise to friendships and hostilities that were both equally unbreakable. They were no doubt one of the deep motors of his theoretical reflection, particularly during that phase of French social and political history from the end of the war until the 1980s, in which occasions for deep hope and despair alike proliferated: a real but unfinished de-Stalinisation; a Eurocommunism that ended up going nowhere; a shattered Union of the Left but the continual renewal of a strategic alliance with the Socialist Party; a communist perspective that persisted but that was inextricably mired in its past.

It was in the grip of these contradictions and the effort to orient and conceptualise them that Lucien Sève’s particular kind of individuality was forged: plausibly, this was also the crucible in which his fundamental interest in a materialist theory of individuality was constructed. This took up the program of a materialist psychology – one previously only sketched by Georges Politzer – precisely because a programme of this kind includes and, above all, renews the question of engagement and of emancipation, that indivisibly individual and collective act. Sève’s analysis could not, then, be separated from a permanent critical introspection – one that, for him, remained fundamentally alien to psychoanalysis. Marx himself had never stopped trying to think the condition of his own historical possibility and that of revolution in the one single movement. ‘You will never be better than your time, but at the best you will be your time’ had been the maxim of the young Hegel, father of modern dialectic and thinker of the Odyssey of consciousness in the world.

Lucien Sève was himself also a major thinker of this living dialectic, through his original concept of the ‘historical forms of individuality’ in which real individuals are constructed:

Biography is to personality what history is to the social formation: it is the history in which the personality, in so far as it succeeds at all, constitutes, activates and transforms itself right up to the end.[12]

On this point, Marx’s contributions remain foundational in Sève’s eyes. He detects in them a theoretical anthropology which connects ‘the thought of the individual formation with that of the social formation in an extremely deep way’. Thus, far from disappearing into strictly philosophical or, even worse, moralising considerations, the question of individuality makes it possible to think of disalienation, in so far as it is a revolutionary task, as a social and political process, and in light of the ‘engaged life’ as well.[13] Sève made the effort to interrogate the PCF’s strategic line from this shifted point of view, not just with respect to its relevance, but also with respect to its renunciations, its capture by short-sighted electoralism, even if this meant neglecting the contemporary question of the role and conquest of the state.

The Manifesto’s formula defining communism as ‘an association in which the free development of each is the condition of the free development of all’ is at the heart of Sève’s rereading of the young Marx’s sixth thesis on Feuerbach – an extensively elaborated reading that he puts forward inMarxism and Theory of the Personality, published in 1969. This thesis, which Sève took the trouble to retranslate himself, states that ‘human essence is not an abstraction inherent to the individual taken on their own. In its effective reality, it is the entirety of social relations.’

On the same occasion, Sève also set out to develop the philosophical category of essence and re-explore in more general terms the question of the Marxian dialectic. This was the other principal component of his work, which he particularly oriented towards a new dialectic of nature, in close dialogue both with contemporary physics and biology,[14] and with the exploration of the ‘philosophical’ in Marx[15] (rather than an exploration of a philosophy supposedly separable from the rest of his work). But, for all this, Lucien Sève never shut himself away in research intended only for initiates, or in a hermetic style – something which a good number of contemporary philosophers at the time made the sign of their jealously guarded originality. His Introduction to Marxist Philosophy, published in 1980,[16] made accessible, while preserving in all their complexity, the key components of his rereading of Marx.

At the same time, continuing to explore the paths of a materialist, anthropologically-oriented psychology and placing biography at the centre of his concerns, Lucien Sève never broke the link with the political stakes inherent in them. It so happened that, from the middle of the 1960s, the lively strategic debate then current within the PCF installed itself, for the purposes of its public expression, on the shifting ground of humanism. This echoed the great post-war theoretical upheavals over the traditional questions of the definition of man, the subject, or freedom – questions on which not only Jean-Paul Sartre, but also Henri Bergson and personalism had been the most recent main spokespeople. Yet this was not the main question.

The controversy between Louis Althusser, Roger Garaudy and Lucien Sève was at the heart of the famous session of the Central Committee [of the PCF] at Argenteuil in 1966. There, Sève went into battle against both the theoretical anti-humanism of Althusser and the philosophical humanism of Garaudy. In a Communist Party which never recognized the right to form tendencies, he acted in close connection with diverging political views, thereby dividing the party from the inside. This situation, among other factors, encouraged the implicit overpoliticisation of theoretical squabbles – ones which today appear byzantine – and risked mixing different discursive registers without ever connecting them to each other. The Argenteuil session – the height of this paradox – settled the question by default, namely by clearly dissociating theory and tactics. At the same time as affirming the absolute freedom of research, it also asserted its utter strategic innocuousness, thereby instituting the divorce between, on the one hand, a kind of tactics determined without any theoretical guidance or debate, and, on the other, a kind of theoretical reflection completely deprived of consequences. Well beyond the PCF, this critical and strategic collapse became general on the Left.

Plausibly, the centrality of the question of individuality, which Sève continually took back to the drawing board, and which loosely united the other dimensions of his research, allowed him to avoid getting bogged down in debates and internal quarrels and all the traps they contained. This did not mean, however, that he did not participate in them. So it was that his approach to individuality, by virtue of its own theoretico-political dynamic, branched off in separate directions, stimulating the revival of the communist question on one side, and on the other feeding an ethical and bioethical reflection which also made no concession to any kind of moralising approach to social reality.

Along the way, the question of alienation in Marx was reexplored. Always relying on the texts, Sève demonstrated just how far this theme never disappeared from the concerns of the author of Capital: his bookAlienation and Emancipation[17] offers a good example of a relation to Marx based on philological rigour and original critical elaboration. Alienation and Emancipation was written in dialogue with contemporary research – even if Sève, except when he was in a polemical mode, often favoured authors close to his own orientations, and also neglected research foreign to French Marxism, which at that time was in the process of becoming provincialised and isolated. Among a number of exceptions to this, it is worth mentioning his link to Lev Vygotsky, the Soviet psychologist of the 1920s, translated into French by his spouse, Françoise Sève.

This tendency could be judged as bureaucratic, but it also sprang from Sève’s friendships. Nonetheless, the fields of research which he laboured were immense. Without any doubt, however, the question of the individual is the focal point around which the other axes of his research were centred and organised: dialectic, communism, sciences, bioethics – fields in which Sève made contributions which it is impossible to detail here. In any case, it is remarkable that Sève always increasingly placed individual emancipation and self-realisation close to the heart of what he called the ‘communist goal’. This was completely contrary to the radical critique of the subject essential to non-Marxist contemporary philosophy and to structuralism,[18] and therefore as remote as it was possible to be from Louis Althusser’s analytical framework and his conception of interpellation, but also from psychoanalysis, which Sève rejected vigorously and no doubt too hastily.

Sève’s extraordinarily complex relationship to Louis Althusser is one of the constants, and also doubtless one of the spectres, at the heart of his trajectory as a theorist and as a person. This is attested by the odd collection of letters from 2016,[19] in which Sève undertook to reply, fifty years later, to letters from Althusser – some of which had never even been sent to him until the directors of the Althusser archive at IMEC [an institute and archive for the history of contemporary publishing] took it upon themselves to do so. From the perspective of this book, the debate on the question of the subject and individuality appears more than ever linked to the personal and the affective, in their simultaneously constitutive and collateral political and philosophical dimensions – in, in short, an inextricable, lived dialectic which certainly goes beyond the concept, but which subtends the incessant effort to construct it.

The books from the 1990s and the following decades are marked by a growing break from politics, counterbalanced by a maintained loyalty to communism, focussing strategic reflection on forms of communist organisation and the way out of its crisis. In them Sève develops the analysis of new – in his eyes – possible forms of organisation of anticapitalist struggle. This question became one of the major themes of his last works: ‘communist action cannot be conducted except in a way that is itself communist: an organisational philosophy that directly and unavoidably extended Marx’s precept that “the emancipation of the workers will be the task of the workers themselves”.’[20]

Sève came to judge as obsolete any perspective based on the taking of power, whether electorally or through revolution, and advocated going beyond the party form, in the belief that ‘an advance into communist strength that will finally be worthy of the name will be proportional to the degree to which the leadership has withered away’.[21] In 2010, Sève left the Communist Party, ‘not,’ he wrote, ‘out of fatigue with communist struggle, but, quite to the contrary, in the deep conviction that today, its crying necessity demands entirely different forms of culture, practice and organisation’.[22]

In his last books, especially in the final, never-finished volume of his tetralogy, the idea of a bifurcation between socialism and communism is asserted more and more. This turns individual development into the marker of an absolutely definite – and wholly questionable – opposition between, on the one hand, recourse to statism and violence, and, on the other, true emancipation. This opposition is of a kind which leaves little room for analysis of class conflict and its mediation, but stakes itself on horizontality and network-formation.[23] This area of theoretical work is all the more vast as it partially takes up the study of two singular historical trajectories, those of the socialist and communist experiments of the twentieth century. In the fourth volume of his Thinking with Marx Today, Sève has no hesitation in proposing a globally negative general historical appraisal, from the USSR to China, via the GDR and Cuba, in conformity with the thesis of prematurity. Without explicitly saying so, this goes back to the problematic thesis of the primacy of the development of productive forces. He writes:

What died under the deeply fraudulent name of ‘communism’ at the end of 1989 with the fall of the Berlin wall, and then in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union, had nothing to do in any deep way with communism in its authentic Marxian sense.[24]

He immediately adds:

If yesterday’s general failure has as its fundamental reason the prematurity of the transition to a classless society, as brilliantly announced by the Communist Manifesto, but with two centuries’ lead over history, then the first and decisive question to ask oneself is this: is the movement towards communism finally coming to historical maturity, in both a local and global way? I think we have major reasons to reply in the affirmative.

Sève then strives to redesign the new pathways of a communism coming into life under our eyes. This is identifiable from the current rise of technological possibilities, the ‘profusion of individuals and people taking their own, and our common, lot into their hands’,[25] the rise of feminism, the multiplication of democratic aspirations, the desires for autonomy and individual fulfilment colliding against capitalist logics with their full force. To this communist goal he frontally opposes socialism, described as constituting a twofold impasse, and as solely responsible for the historical drama of the twentieth century:

Socialism, even at the risk of otherwise sinking into opportunism and class collaboration, thus presented itself as necessarily united with violent revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat.[26]

From now on the question becomes one of envisaging ‘the surpassing of capitalism as an immense set of qualitative transformations, no longer in the first instance abrupt ones, but of a continuously gradual kind’.[27] How, though, could this kind of calm transformation be set in motion under the domination of authoritarian neoliberalism? The analysis stops short at a climactic point: the second volume of the fourth part, which remains unfinished, had this very question of the transition to communism as its object. Whatever one may think of this political option, it has the unambiguous advantage of reoccupying the terrain, today largely abandoned, of strategic reflection in the full sense of the term.

Lucien Sève’s death comes at the exact moment when, without any possible ambiguity, dramatically combined crises of capitalism mark the real start of the twenty-first century. As its legacy it bequeaths us a twofold task: that of pursuing a reflection that distances Marxism from any pure ‘Marxology’, any return of Marx into the scholastic comfort of the ‘classic authors’ or a philosophical retreat into disengagement; and that of reviving the fundamental debate – a collective one – on the question of the political alternative to capitalism and the means of its social and political construction, including the question of organisation.

The recent death of several political Marxists of this generation, such as André Tosel or Daniel Bensaïd, who all shared similar concerns and suggested different ways forward, must be made the occasion to reexplore this history in order to take it up again and readjust it to present circumstances. Their contribution, barely known today, and overshadowed by a post-Marxism that, for all its refinement, comprehensively deserts the question of the alternative to capitalism, has not been widely disseminated, as it deserves to be. Reactivating a political Marxism aware of its own history is an urgent task. In bequeathing us his share of that history, Lucien Sève has left us a hugely rich legacy – of that, there can be no doubt.

By Isabelle Garo.

Translated by Nick Riemer

[1] Lucien Sève, Pour une critique de la Raison bioéthique, Paris, Odile Jacob, 1994, p. 342.

[2] Introducing the law on research programming, Antoine Petit declared on November 26 2019, in an opinion piece published by Les Echos [the principal French financial daily] ‘We need an ambitious and unequal – yes, unequal – law; a dizzying and Darwinian law which encourages the scientists, teams, laboratories and institutions that perform best at the international level, a law that gets the energy moving.’

[3] Lucien Sève, Qu’est-ce que la personne humaine ? Bioéthique et démocratie, Paris, La Dispute, 2006, p. 103.

[4] Lucien Sève, « Les « dons » n’existent pas », L’École et la Nation, 1964

[5] Sève recounts this episode in the first part of his tetralogy (« Court post-scriptum sur Marx et moi », Penser avec Marx aujourd’hui, I. Marx et nous, Paris, La Dispute, 2004, pp. 249ff.); detailed biographical information can be found in the entry in the Maitron dictionary written by Jacques Girault (https://maitron.fr/spip.php?article173192).

[6] Lucien Sève, Penser avec Marx aujourd’hui, I. Marx et nous, Paris, La Dispute, 2004, p. 259.

[7] This translation project continues today as the GEME (Grande Édition des œuvres de Marx et d’Engels en français [Standard Edition of the Works of Marx and Engels in French]), which Sève worked towards establishing.

[8] Lucien Sève, Penser avec Marx aujourd’hui, IV, 1ère partie, « Le communisme » ?, Paris, La Dispute, 2019, p. 28.

[9] Lucien Sève, Une introduction à la philosophie marxiste, Paris, Édition Sociales, 1980, p. 617.

[10] It is worth reading Sève’s reply to the caricatural analysis presented by Frédérique Matonti (Intellectuels communistes – Essai sur l’obéissance politique: La Nouvelle Critique (1967-190) [Communist Intellectuals – Essay on political obedience: La Nouvelle Critique (1967-190)], Paris, La Découverte, 2005) in an article entitled ‘Intellectuels communistes: peut-on en finir avec le parti pris?’ [‘Communist intellectuals: can we finish with the prejudice?’] (Contretemps n°15, Paris, Textuel, 2006, http://www.contretemps.eu/wp-content/uploads/Contretemps%2015.pdf)

[11] Perry Anderson, Considerations on Western Marxism. London, NLB, 1976.

[12] Lucien Sève, Penser avec Marx aujourd’hui, II. « L’homme » ?, Paris, La Dispute, 2008, p. 514.

[13]ibid., p. 511.

[14] Lucien Sève (in collaboration with scientists), Sciences et dialectiques de la nature, Paris, La Dispute, 1998 andÉmergence, complexité et dialectique, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2005.

[15] Karl Marx, Écrits philosophiques, présenté par Lucien Sève, Paris, Champs/Flammarion, 2011.

[16] Lucien Sève, Une introduction à la philosophie marxiste,op. cit. n. 9.

[17] Lucien Sève, Aliénation et émancipation, Paris, La Dispute, 2012.

[18] Lucien Sève, Structuralisme et dialectique, Paris, Messidor-Éditions Sociales, 1984.

[19] Louis Althusser, Lucien Sève, Correspondance, 1949-1987, Paris, 2018, Éditions sociales.

[20] Lucien Sève, Aliénation et émancipation,op. cit. n. 17, p. 90.

[21] Lucien Sève, Commencer par les fins – La nouvelle question communiste, Paris, La Dispute, 1999, p. 196.

[22] Lucien Sève, Penser avec Marx aujourd’hui, IV, 1ère partie, « Le communisme » ?, op. cit. n. 8, p. 29.

[23] Lucien Sève, Commencer par les fins,op. cit. n. 21, p. 196.

[24] Lucien Sève, « Le « communisme » est mort, vive le communisme ! », interview with Pierre Chaillan, L’Humanité, 8 novembre 2019 (https://www.humanite.fr/le-communisme-est-mort-vive-le-communisme-679952)

[25]ibid.

[26] Lucien Sève, Commencer par les fins, op. cit. n. 21, p. 50.

[27]ibid. p. 119