Miriyam Aouragh writes on the recent protests in Morocco following the death of Mohsin Fikri

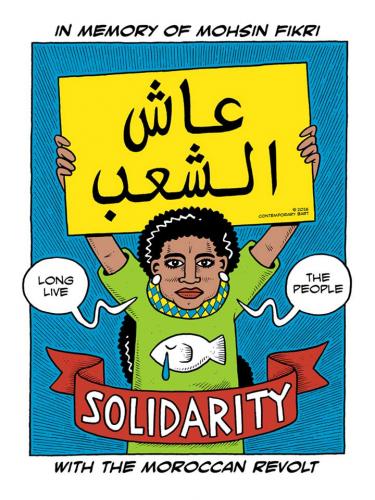

Poster by Contemporary Bart

As Morocco’s streets roiled with protest, we looked with astonishment and even mistook some of the videos for scenes of the 2011 uprisings. It is not an exaggeration to say that, yet again, the whole country rose up. Hundreds of thousands of people are protesting across the country chanting ‘al sha’b yourid isqat al fasad’ [the people demand the downfall of the corrupt] or ‘tahiya nidaliya, al hoceima thawriya’ ‘[salute to the uprising, al hoceima is our revolution]. The protests quickly spread to more than 40 cities. They then reverberated in the major cities of France, Spain, Belgium and the Netherlands where most of the Moroccan diaspora reside.

These protests began after a fish seller was crushed to death in the northern Mediterranean town of Al Hoceima. The story of Mohsine Fikri is gruesome and particular but also symptomatic. He jumped into the garbage truck with a few other colleagues to protest the embezzlement (and waste) of their fish, which was ordered by the police and the well-connected merchant controlling the retail of fish. Witnesses said the police then ordered the driver to set-off the trucks grinder-system. Mohsin’s colleagues managed to jump out in time, but he got stuck behind.

One of the policemen sarcastically commented “than mo”, which is loosely translated asgrind the mother. Mother is both a contraction of a well-known derogatory swearword in whichmo/k revers to ‘mother’, and denotes the Darija (Moroccan Arabic) mostly spoken by non-Amazigh policemen enlisted in the area. Historically, these men are sent from central Moroccan army barracks to control and intimidate Amazigh locals, mostly with impunity. Their interactions are often disrespectful, loaded with references to imazighen as inferior people. So the hashtag♯than_mo has a deeper meaning for imazighen than appears on the surface. “Than ‘mo” went viral on social media, often joined by photos displaying the gruesome act. When the photos and videos of Mohsin and the first protests circulated that same day, the spontaneous movement became a fact authorities could not ignore.

The outrage led to mass rallies, although mostly spontaneous they often including previous 20 February activists, the nation-wide network behind the demonstrations during the Arab uprisings of 2011.

Sensing the jeopardies that come with these these trans-local steadfast collaborations, the furious mood as well as the awareness that smaller incidents can spark major transitions, the political elite of the Makhzan [Moroccan reference to the state structure which is itself an intricate part of the palace] almost immediately pledged to conduct an investigation. Officials form different ministries and parties ordered to visit Fikri’s family and persuade them to quell the protests. King Mohammed 6 and ministry entourage have also tried to sway the dynamic back to ‘normal’. Although there have been arrests (and in the un-exposed villages and smaller cities the response remains violent), the police and army are mostly restrained. This unusual response signifies how puzzled the regime is. The fact that this week the Kingdom hosts the COP22 climate conference has augmented apprehension over their response.

Hyper-capitalism with a crown

The events reflect different important things simultaneously. There is the recurring manifestation of anger over careless police repression, as people are tired of the unhindered behavior of the security forces, often showing its monopoly over violence and authoritarian policies in a spur-of-the-moment such as that fatal day for Mohsin. But it is also a continuation of the explosion of anger and protest in 2011 across the Arab world – including the Maghreb with its many non-Arab communities and political minorities, such as the imazighen in the northern and southern parts.

As was important to note in 2011, these are not just protests against repression and violence typical of a police state. Dictatorships cannot be understood outside of their larger political-economic context. We find with Morocco a very complex reality caused by the sort of unlimited-privatization and hyper-capitalism that transfers its for-profit logic onto a much more harshly controlled trade of (mostly local) fishery. This regional and national problem is felt very clearly in Morocco’s coastal cities and towns. For instance, we see this in Al Hoceima, where many people are dependent on fish and have been selling fish independently for a long time. Fish and fishery, the coast and the sea are part of the social fabric. All the new rules and regulations, to the point of violent prevention of personal retail, are experienced by residents and fishers as aberrations to normal life. These incidents are testimonies of how economic liberalisation impose undesirable socio-cultural changes. But the contradiction is that they also encourage resistance.

Analysis of these protests needs to incorporate how millions of ordinary people are confronted with critical socio-economic shifts caused by Morocco’s extreme neoliberal policies. This dynamic is in addition to crucial local and historic issues such as the demand for local sovereignty (e.g. to allow local fish and crops to benefit the community instead of a few well-connected (me’rifa) businessmen) and democracy with particular demands for accountability of police repression.

However much these swift and raw public spasms are confirming that social tensions have reached a tipping-point, these are not new. Since independence in 1956, Morocco has provided both a geopolitical and economic sphere of influence, including in particular the northern regions because of their geographic locations connecting Africa, Europe and the Middle East — this was after all, the main motive for the international status of Tangier for a very long time, the poster-boy that provided Africa its largest and oldest tax-free manufacturing zones. And this historic exploitation and suffering is why it matters that the protests erupted in the northern Al Hoceima region, also known as the Rif.

History cuts like a knife

Morocco was occupied and colonized by France and Spain, and Spain was the colonizer in the north. And it was a particularly harsh colonization in the north. The legacy is stained by colonial violence and this history still cuts like a knife. The Northern regions have a particular history of unrest, since the Rif is also the birthplace of Abd el-Krim al-Khattabi, one of the most important anticolonial resistance fighters in the early 1920s, respected across the Arab world, Africa and what was previously known as “Third World”.

Moroccan independence differed from other liberation movements, most importantly nearby Algeria. It was an agreed transition with the colonizers. In the north, some of the fiercest battles were fought (and, remarkably, often won) where people suffered unimaginable violence for decades. Medical and scientific reports about the lasting effects of mustard-gas aerial attacks are still on-going. The local consensus was to continue the struggle. They wanted real independence, one that included the right to determine their own future with respect for the regional Amazigh culture, language and politics. This blew up during the Rif insurrection in ’58-59, which was crushed by the then-new kingdom of Mohamed 5 and in which crown-prince Hassan 2 personally participated (See filmBriser Le Silence). This is a very painful part of the memory of the Rif and the general sense there is that people do not forgive or forget. But the makhzan doesn’t let people forget.

These memories are prompted every time the people rise up and are suppressed again, as occurred during the Intifadas of 1981, 1984, 1991. Al Hoceima (mostly as part of the Food Riots in the rest of the country in response to IMF imposed cuts or planned privatization of education) experienced major uprisings. Some were actually initiated and led by young school students and spread throughout the north of the country. So those memories are continuously refreshed and in due course become part and parcel of the syntax of certain politically involved citizens.

But all of these previous experiences culminated in 2011. Those who were politically involved were able to disseminate these memories – and all the lessons derived from them – to a new generation of activists. This is crucial because as is typical for any dictatorship, for decades there has been a very strict censorship of the political history of Morocco, at least until the early 2000s around the time the new King Mohammed 6 took over the throne when his father Hassan 2 died and understood the regime had to adapt. But it seems that in the last few weeks reached a limit, “than mo” was the last straw broke the camels back. The placards carried at protests (often joined if not led by women) saying The Rif Does Not Kneel is the ephemeral retribution of the incessant and compulsory obedience.

Caption placard: The Rif Does Not Kneel. Photo by Mohammed El Asrihi]

Unfinished Business

While many didn’t really know about these histories, not even of the epic anti colonial resistance of the 1920s and the massacre at the hand of their own government during the 1950s insurrection, it all haunts the Rif. They then merge with more recent experiences of 2011. We could see the current uprisings as an opportunity for those old and recent memories to converge. Indeed, during the 20 February protests in Al Hoceima five demonstrators were killed and their corpses moved to another location where they were burned to hide evidence. When people reject the promises to investigate the death of Mohsin Fikri, they recall these 5 young men.

Those cases were never resolved despite promises to conduct honest investigations. So there is a certain unfinished business – both a feeling of unfinished business in Al Hoceima in terms of its history and repression by the makhzan, and with the rest of the country with regards to the movements that arose in 2011-12 and were successfully quelled through government cooptation and the promises of new constitution and elections.

Makhzan Public Relation

Marrakesh will host the 22nd COP UN climate summit. All the official climate-related motives notwithstanding, this cannot be separated from other political interests of the Kingdom. There is an interesting international development with regards to Morocco’s attempt to become part of the international community. Morocco has invested enormously in its PR over the years. Ironically, one of the major recipients of funding has been the Clintons and especially Hilary Clinton in anticipation of her Presidency (activists are currently sharing sarcastic statements to claiming back their tax-funded gifts). A number of reports (diplomatic cables known as “Marocleaks”) exposed how the Moroccan makhzen employed PR advisers, some belong to Brookings and others agencies affiliated with pro-Israeli lobby firms (See Intercept). In other words, organizations that are experienced in rebranding unacceptable policies or states, that sell dictatorships as democracies. In Morocco this is mainly related to the controversy over Western-Sahara.

The invitation of big organizations and NGOs to Morocco to organize their conferences is one of the ways the Moroccan state is trying to improve its international stature. We saw that with the international Human Rights conference two years ago. Many human rights activists and lawyers were very angry about this charade, for while these conferences took place human rights in Morocco were crushed. The level of cynicism and sometimes irony in all the hashtags, posters and banners are precisely about exposing that fierce contradiction. A country that is organizing international conferences about climate change or democracy, and at the same time not offering any of those rights to its own citizens. But this week the activists are reminding the delegates of their disillusionment with these attempts, as one poster says, “Come to COP 22. We will crush you,” in reference to the crushing of Fikri.

The past weeks in Morocco are therefore both similar and different from the uprisings in 2011. Mainly, the extremely challenging (and then very new) experiences of 2011-2013 are behind them. Many of the lessons have been learned, often in tragic ways. Hence, activists now expect to see state manipulation of the protests. Besides the orchestrated efforts of all the official media, some confirm that infiltrators were sent to the different protests across the country. The people have no illusions in the promises of a government, which uses its networks of spies to spread rumors about the protests as anti-Arab Amazigh sectarianism, about the activists being Algerian spies, or influenced by Polisario provocateurs. As this new chapter in Moroccan politics reminds us, ordinary people bare the brunt of the Makhzan and therefore change can only come through a united effort across ethnic, linguistic and regional class.