In 1896, a new electric tram began service in the Saxon city of Dresden. Eleven days later, the incomprehensibly horseless carriage ran over a four-year-old boy. Fritz Globig’s lower right arm had to be amputated, and the trauma defined the rest of his life.

In childhood, he realized that he needed to stand up for himself — he could never back down. Later, as his generation was drafted into the First World War, the one-armed Globig got an exemption from military service. These two characteristics let him become a leader of the socialist youth movement in Germany. He was the youth delegate at the founding congress of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

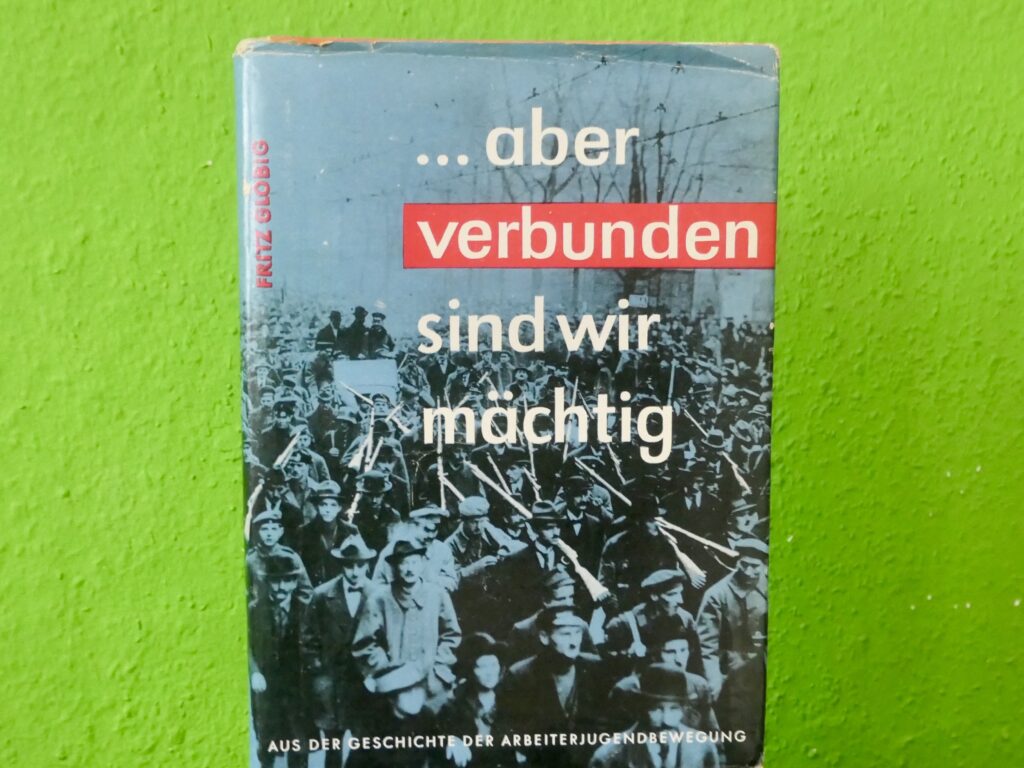

In 1958, Globig published recollections from his youth: …But United We Are Powerful: From the History of the Working-Class Youth Movement.[1] This 334-page East German volume, with a surprisingly modern design for the Ulbricht era, provides lots of personal anecdotes from the November Revolution of 1918-19 — alongside endless Stalinist clichés.

This book belongs to a genre of East German revolutionary memoirs. The Socialist Unity Party (SED) had put out a call to commemorate the revolution’s 40th anniversary by putting memories down in writing.

Hearts Burning

Globig starts at the beginning: his father was a poor, deeply religious tailor in Leipzig. Once an independent craftsman, he had to take a job in the factory to feed his eleven children. At 14, the young Globig entered working life with an apprenticeship as a Chemigraph: an engraver making coloured prints of paintings for art books. The top floor of the printshop was away from the din, but also full of toxic chemicals. Here, Globig joined the union and then the working-class youth movement led by Social Democracy. This process of politicisation required extensive reading: not just political economy, but also the classics of German literature.

As he became more active in the youth movement, Globig got to know the “Interna” of Leipzig’s Social Democratic Party (SPD)— other sources refer to it as the “Corpora.”[2] This secret body of old fighters from the time of Germany’s Anti-Socialist Laws (1878-1890) was supposed to keep the party on the right course: only proven comrades were invited to meetings where the actual decisions were taken about posts in unions, cooperatives, and party organisations. Yet, for Globig’s radical young comrades, these old fighters represented a conservative bureaucracy.

After four years as an apprentice, Globig’s Wanderjahre, his years of travel, took him to jobs in Stuttgart, Dresden, and Geneva. In Stuttgart, he began to identify with the SPD’s far-left wing, including Fritz Westmeyer, Clara Zetkin (with her jibes against “wannabe ministers”), and, above all Karl, Liebknecht.

The rest of Globig’s book is full of hagiographical praise for Liebknecht, who was a champion of the independent socialist youth movement in their constant wrangles with the party bureaucracy, years before he became a global working-class hero for his opposition to the First World War. The constant repetitions about young hearts burning when Liebknecht spoke can sound cheesy, but, for a generation of young men condemned to death in the trenches, Liebknecht really did have a secular halo.

Even before the big betrayal of 4 August 1914, the revolutionary left in the SPD had noted the party’s slow process of adaptation to the German Empire. Globig recalled the “Panther Leap to Agadir” in 1911, when Kaiser Wilhelm sent the cannon boat SMS Panther to the Moroccan port city and almost provoked a war with France. In this Second Morocco Crisis, the “Marxist Centre” of the SPD leadership had remained completely passive, while Rosa Luxemburg demanded energetic opposition.

Jena Conference

As a German citizen working in Switzerland, Globig had to return to his country when the Great War broke out — but his missing arm saved him from service. Facing unemployment for the first time in his life, Globig moved to Berlin on 15 February, 1915. Just a month later, on 18 March, 600 socialist women gathered in front of the Reichstag for the anniversary of the 1848 revolution. Following a long tradition of the Berlin workers’ movement, they were honouring the “March Fallen” who had died on the barricades. This protest was not only a celebration of the recently established day of struggle for working women, but also the first demonstration against the war.

All the leaders of the SPD publicly supported the War, but their young comrades were markedly less enthusiastic. Just a month after the mobilisation, in September 1914, socialist youth started meeting in a beer garden in Neukölln, then a city south of Berlin, called Karlsgarten.[3] They were soon joined by Liebknecht, and on 12 March 1916, they founded a Youth Education Association of Greater Berlin as a cover for their anti-war activities.

On 1 January 1916, Globig was the youth delegate at a meeting in Karl Liebknecht’s law office on Chausseestraße. This is where the “resolute Left” (entschiedene Linke), as they called themselves at the time, founded the Spartacus Group — though they were first known as the International Group, and only got the name Spartacus later that year. Globig offers reminiscences from the “frog perspective,” as the Germans say. During the lunch break, the delegates sat at Aschinger, an enormous chain restaurant with cheap pea soup, sausages, and beer, and discussed their perspectives, with Käthe Duncker arguing to remain in Social Democracy as long as possible, while Johann Knief from Bremen called for a quick break.[4]

Globig offers a balance sheet of this debate on whether and how to break from the SPD, and later the Independent Social-Democratic Party (USPD), which I quoted in a recent article about the pre-history of the KPD.[5] He argues that “the SPD leadership did not fear a split, but the Left did.” While young socialists had already broken ties with the official youth leaders in 1915 over their pro-war positions, it took the Spartacists until the very end of 1918 to part ways with reformists and centrists. Globig recalls that this “weakness of and half-heartedness of the Spartacus leaders” had not impressed the young people eager to raise a new banner.

With the support of Karl Liebknecht, 62 oppositional youth from 18 cities across Germany used the long Easter weekend in April 1916 to organize a secret conference in Jena. Following this meeting, they began publishing an illegal newspaper (Freie Jugend, Free Youth) and held mass meetings out in the forest far away from police — Globig recalls a hike with 2,000 young people on 5 May 1918, to celebrate Karl Marx’s 100th birthday.

The Easter Conference in Jena is where the revolutionary wing of the youth movement began to organise, culminating with the formation of the Free Socialist Youth (FSJ) two years later. On 26-28 October 1918, just before the revolution broke out, the FSJ held its founding conference in an impressively modern office building in central Berlin, the Schicklerhaus, that contained the headquarters of the Berlin USPD and later the Marxist Workers’ School (MASCH). An East German historical plaque recalling the FSJ congress has long since disappeared — the building has since been taken over by a criminal realty speculator.

Buy a Ticket

Three days earlier, Liebknecht had arrived in Berlin, after an amnesty by the new “liberal” government installed to be the public face of Germany’s capitulation. Globig was in front of the station, together with thousands of workers trying to reach the platform and greet their hero when his train pulled in at 5pm. They were blocked by police, but Globig got past them by buying a ticket. Thus, Globig’s book is one source of the best — though probably not quite accurate — joke about the German revolution:

“Revolution in Germany will never work. When these Germans want to occupy a train station, they first buy a platform ticket!”[6]

When the revolution arrived on 9 November 1918, Globig helped storm the Police Presidium at Alexanderplatz — Berlin’s notorious Red Castle — and his partner Marta Globig helped set up Berlin’s new revolutionary police force under the socialist journalist Emil Eichhorn.[7] In the following stormy weeks, Globig was at all the most important meetings and struggles. He joined the national conference of the Spartacus League on 30 December, where they voted to finally leave the USPD. The next day, he was the youth delegate at the founding congress of the KPD. When the Berlin workers attempted an insurrection in early January 1919, Globig was one of the fighters who occupied the Mosse publishing house. Now, despite his disability, he took up arms. But, once the other occupations had been defeated, the 30 or so young people decided to flee the building and go into hiding.

The second FSJ conference met in February of 1919, in the Prince Albrecht Palace, which just a few years later became the Gestapo HQ. Globig’s narrative ends in September 1920, when the third FSJ conference renamed itself the Communist Youth League of Germany (KJVD).

East German Biography

Globig’s book was one of many published in East Berlin for the fortieth anniversary of the revolution. The most monumental of them was the 584-page volume Vowärts und nicht vergessen! (Forward and don’t forget), including 36 different recollections. In an introduction, Stalinist party boss Walter Ulbricht laid down the line regarding the correct historical interpretation of 1918-19.[8] I have translated the best account from that book for Verso.[9] There were also standalone volumes such as this one and the memoirs of the young soldier Fritz Zikelsky.[10] Another collection included a few dozen more recollections.[11] At least one book-length manuscript, by Ewald Ochel, landed in an archive and only published 60 years later for the revolution’s centennial.[12]

All these books are great, even though they need to be read with a critical, even a downright suspicious eye. Writing an autobiography is always a process of selecting — this can lead to disappointing results when the story of a young revolutionaries has to be told by an old cynic. In the case of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), in the iron grip of Ulbricht, the selection must have been particularly intense. Reading this book, one would love to ask Globig how he looked back on his life at age 66.

According to the Biographical Handbook of German Communists, Globig had a dynamic career in the KPD in the 1920s, editing Communist newspapers in different cities and serving in the Bremen parliament, before he moved to the Soviet Union in 1930 to work at the Workers’ International Relief. He had never been part of an opposition faction, but as the Great Purges ramped up, any previous contact with “dissenters,” even with fanatically loyal Stalinists who had fallen out of favour for unknown reasons, was enough to get arrested. In 1934, Globig got an official “reprimand” in 1934 for speaking with “Trotskyists” — who were emphatically not Trotskyists. In 1937, he was arrested and sentenced to ten years in a Gulag, and was later sent into exile in Karaganda in Kazakhstan. In 1943, his wife divorced him as a traitor.

He returned to Germany in 1955, a quarter of a century after he left, and the GDR rehabilitated him. Globig served on in the local SED leadership in Leipzig, and worked as a historian, contributing to the eight-volume History of the German Workers’ Movement (published in 1966) and writing his memoirs.

How did Globig reflect on 25 years of imprisonment and banishment under a system he supported? What did he think of the GDR’s recalcitrant process of de-Stalinisation after the dictator’s death? He does not appear to have written this down. Even the heroic period covered in this volume has been subject to crude censorship — though it is not clear whether Globig or an unnamed editor was doing the censoring. The original manuscript could quite well be in the SAPMO Archive if anyone wants to check.

Memory Hole

The day after Liebknecht returned from prison on 23 October 1918, a reception was held in his honour at the Soviet embassy on Unter den Linden. Globig dedicates several pages to the event and the speeches made by different attendees, but scrupulously avoids mentioning the Soviet ambassador’s name, even when quoting him directly. It was Adolph Joffe, a comrade of Trotsky, committed suicide in protest against Stalinism in 1927.

Similarly, Globig describes the preparations for the founding meeting of the Communist Youth International (CYI), which opened in the back room of a Neukölln bar on 20 November 1919. The “Secretary of the Russian Communist Youth League” stayed at Globig’s apartments for several weeks. Yet, despite several pages of anecdotes about him, again the name is missing. It was Lazar Shatskin, a Komsomol leader and later a dedicated Stalinist, who nonetheless fell out of favour in 1930 and was shot in 1937.[13]

Instead of these disappeared figures, we get the names of people who three decades later aligned with the GDR, like Wilhelm Pieck and Fritz Heckert, who certainly played big roles in the November Revolution, yet might nonetheless be overemphasised here.

It is not easy to find source material about the November Revolution. So many of the participants were killed before they could write their memoirs: by “democratic” counterrevolution, by fascism, or by Stalinism. Memoirs written after the war in West Germany, such as the wonderful book by Karl Retzlaw, could be written with a bit more freedom — yet Retzlaw also edited his memories as a result of his wartime capitulation to British imperialism.[14] Hence, East German books like this one, made with great care, are an invaluable resource for anyone who wants to understand the lost potential of 1918.

[1] Fritz Globig, ...aber verbunden sind wir mächtig. Aus der Geschichte der Arbeiterjugendbewegung (Berlin (East): Verlag Neues Leben, 1958).

[2] Paul Fröhlich, In the Radical Camp: A Political Autobiography 1890-1921 (Leiden: Brill, 2020), 71-75.)

[3][3] While this particular beer garden no longer exists, Neukölln still has a street and a school named Karlsgarten that mark the spot.

[4] There is not nearly enough information about Knief, who later led the Bremen Council Republic, available in English. See: Gerhard Engel: “The International Communists of Germany,” in: Ralf Hoffrogge / Norman LaPorte (eds.): Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918-1933 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2017).

[5] Nathaniel Flakin, “An Overdue Birth: Rosa Luxemburg and the Founding of the KPD,” Left Voice, 20 January 2025.

[6] For my retelling of this joke, see Nathaniel Flakin, Revolutionary Berlin: A Walking Guide (London: Pluto, 2022), 48. This quote is often attributed to Lenin, but he is almost certainly not the author. It might actually come from a 1931 interview with Stalin, in which the dictator was telling an anecdote from 1907, hence unrelated to the German revolution. In any case, Globig’s testimony shows there was at least one German revolutionary who bought a ticket in order to meet Liebknecht.

[7] See “Marta Globig,” in: Vowärts und nicht vergessen! Erlebnisberichte aktiver Teilnehmer der Novemberrevolution 1918/19 (Berlin (East): Dietz, 1958), 301-10.

[8] Was it a bourgeois revolution? A proletarian one? Ulbricht offers Stalinist gobbledygook: It was a “bourgeois-democratic revolution that was carried out, to a certain extent, with proletarian means and methods.”

[9] Cläre Casper-Derfert, “Get up, Arthur, today is revolution!!”, Verso Blog, 18 November 2021.

[10] Fritz Zikelsky, Das Gewehr in meiner Hand: Erinnerungen eines Arbeiterveteranen (Berlin (East), Verlag des Ministeriums für Nationale Verteidigung, 1958

[11] Unter der roten Fahne: Erinnerungen alter Genossen (Berlin (East): Dietz, 1958.

[12] Ewald Ochel, „Was die nächste Zeit bringen wird, sind Kämpfe”: Erinnerungen eines Revolutionärs (1914–1921) (Berlin: Metropol, 2018).

[13] Readers will be able to learn lots about Shatskin in the forthcoming English-language publication of the proceedings and resolutions of the early congresses of the Communist Youth International, in a volume being edited by Mike Taber and Bob Schwarz, to be published soon by the Historical Materialism Book Series (Brill and Haymarket).

[14] Karl Retzlaw, Spartakus: Aufstieg und Niedergang — Erinnerungen eines Parteiarbeiters (Frankfurt: Verlag Neue Kritik, 1971)