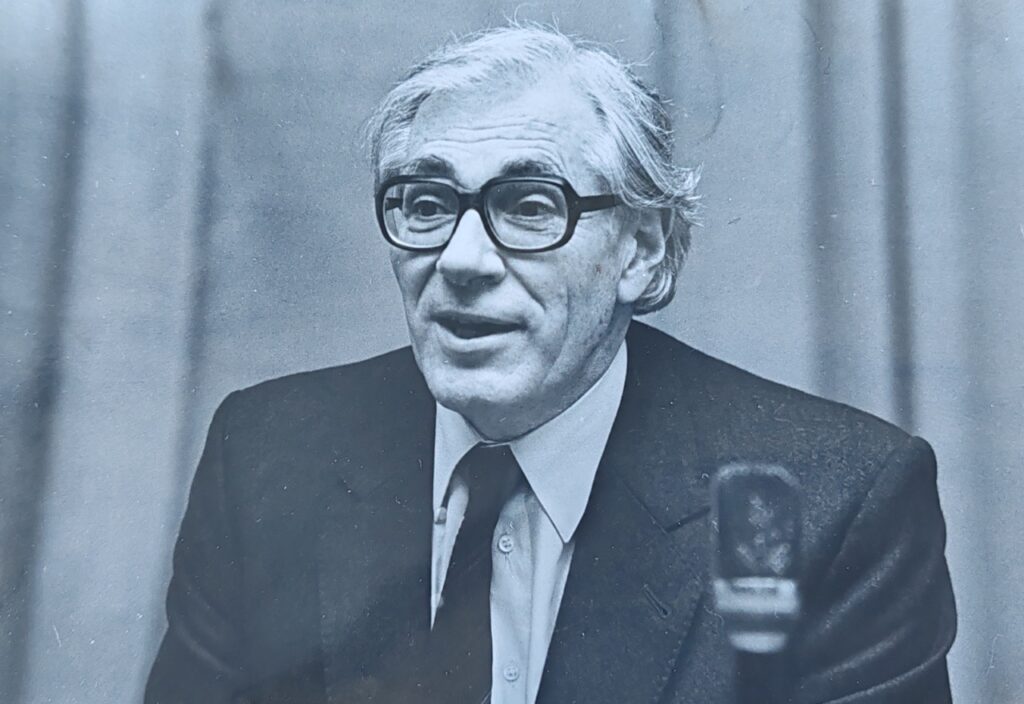

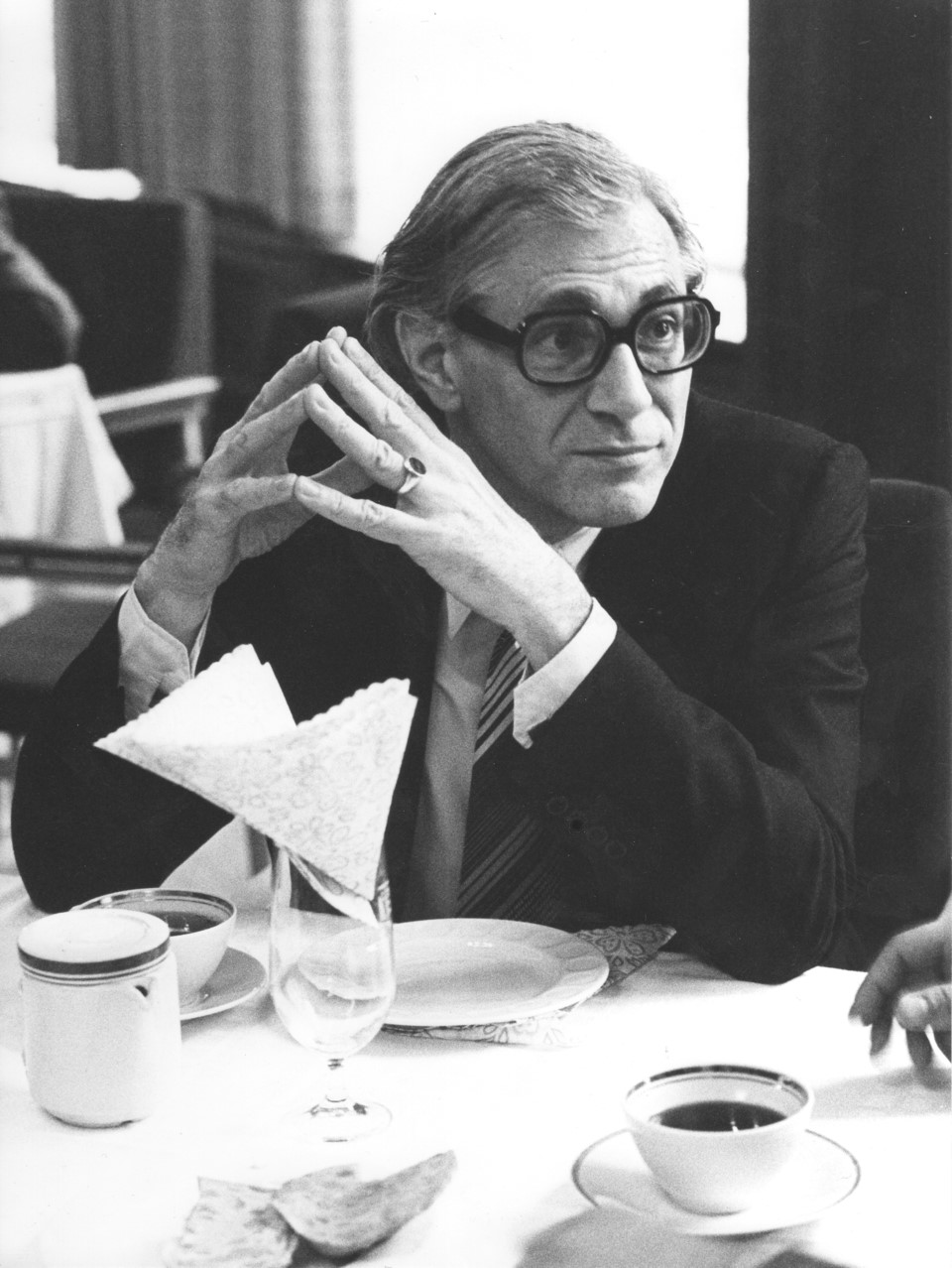

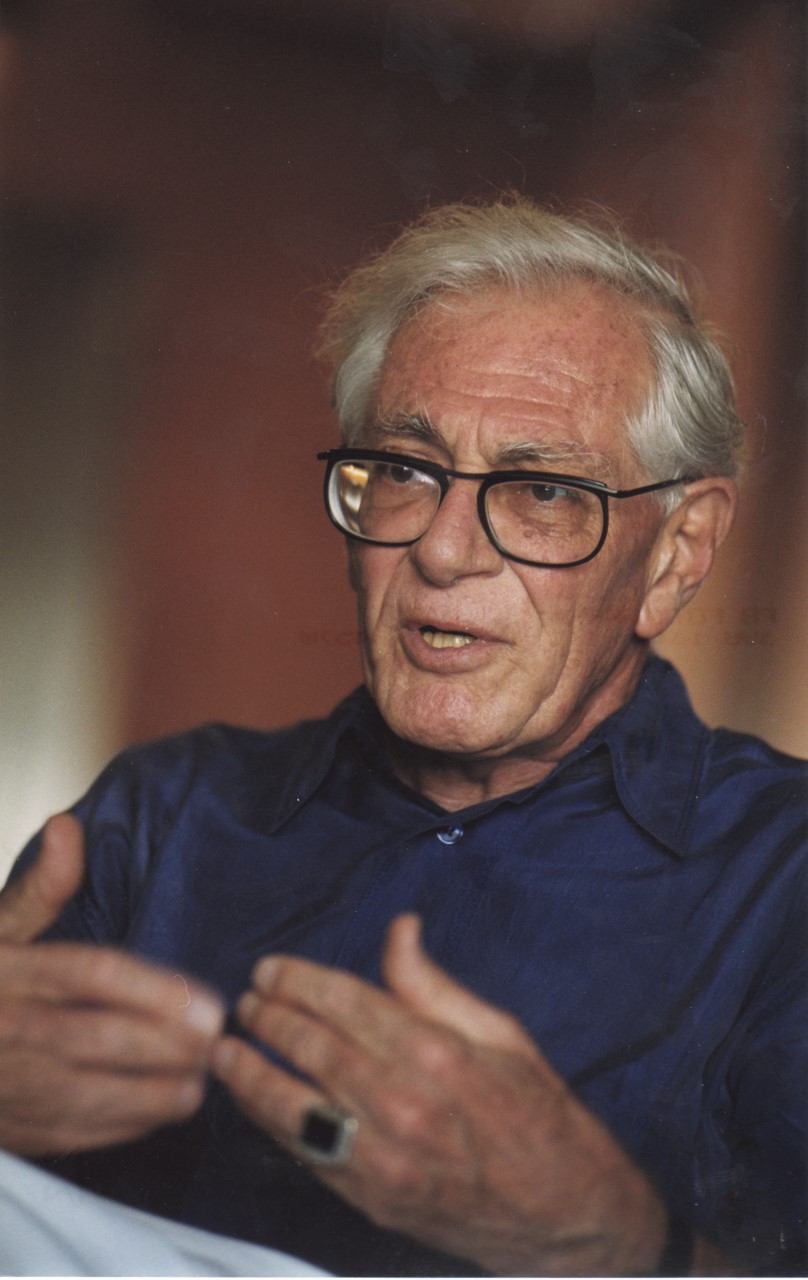

Hans Heinz Holz (1927–2011) was one of the most outstanding and eminent Marxist philosophers of the second half of the 20th century. As he described in interviews shortly before his death in February 2011, his involvement in the resistance against National Socialism as a high school student marked the beginning of his intellectual development.[1] Incarcerated by the Gestapo, he became acquainted with a fellow inmate—a communist—who introduced him to Marxism.

After the Second World War, Holz worked as a journalist and earned his Ph.D. as a West German in the GDR with a thesis on Herr und Knecht bei Leibniz und Hegel (Master and Slave in Leibniz and Hegel), supervised by Ernst Bloch. Holz had been planning to move to the GDR since the early 1950s. However, the Hungarian Uprising of 1956 and the formation of the so-called ‘Harich Group’ (Wolfgang Harich, Walter Janka, etc.)—which, among other things, demanded the removal of party and state leader Walter Ulbricht—led to Bloch falling out of favour. Bloch had maintained links with Harich and did not approve of the Soviet invasion of Hungary. His resignation was accompanied by a political campaign against his philosophy.

As a consequence, Bloch was no longer able to award Holz his doctorate in 1956, and it became impossible for Holz to move to the GDR. In 1957, Bloch left the GDR and thereafter lived in the FRG. Holz was eventually able to complete his doctorate in Leipzig in 1969.

In a vein similar to Bloch, Holz was convinced that classical philosophy and metaphysics are an indispensable heritage of Marxism. The influence of Leibniz and Hegel is therefore crucial for understanding Holz’s philosophy. In the 1950s and 1960s, he worked as a feature writer and independent scholar. Despite his journalistic work, Holz aspired to an academic career. After political opposition from conservative and social-democratic circles in Bern and West Berlin prevented him from obtaining a habilitation and professorship, he was finally appointed Professor of Philosophy in 1971 with the support of Wolfgang Abendroth, his disciples, and students in Marburg.

In 1979, he joined the philosophy department at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, where he worked until his retirement in 1997. Thereafter, he published comprehensive systematic and historical works on aesthetics,[2] dialectics,[3] and the history of dialectics.[4] Holz died in his house in San Abbondio, Switzerland, in 2011.

Holz’s efforts to integrate the entire theoretical tradition of metaphysics into his own conception of dialectical philosophy in the second half of the 20th century were aimed at counterposing a contemporary conception of rational praxis to the irrational tide of events of the time. Throughout his life, Holz pursued the programme of uniting materialism and metaphysics within dialectics—without losing sight of the fact that its realisation is inseparably linked to the scepticism of the hypothetical. In line with this programme, the subtitle of his major systematic work Weltentwurf und Reflexion (World Model and Reflection) is Versuch einer Grundlegung der Dialektik (Attempt at a Foundation of Dialectics). The term ‘attempt’ reflects an insight drawn from Leibniz: metaphysical models are always hypothetical and transitory. After all, how else could a five-volume history of dialectics have been written?[5]

Moreover, the subtitle reveals another dimension of Holz as a Leibnizian thinker: a world model that proceeds from the plurality and perspectivity of the perception of the world can only ever be an attempt at founding dialectics, for it presupposes that other such attempts are both possible and necessary.[6]

In what follows, we will trace both the singular historical signatures and, more importantly, the intrinsic historical content of Holz’s philosophy—that is, the historical conditions under which his model of dialectics took shape, and the epoch-making significance of that model. To this end, we will draw on a philosophical testimony: a series of lectures Holz delivered at the University of Girona in 2001—a kind of intellectual autobiography, recently published in German.[7] These lectures begin with anecdotes about the liberation from Nazi tyranny, signifying both a personal and a world-historical experience: the adolescent’s perception of liberation, which had yet to become an awareness of freedom as the fulfilment of reason in history. It is striking to observe, while reading these lectures, how personal points of departure and individual motivations are inscribed into the very structure of Holz’s thought.

For instance, Holz reads Sartre through the lens of Sartre’s historical influence, drawing from him the foundation of a problem that goes well beyond its immediate context, namely:

How is it possible to weave the self-certainty of the subject—which finds an evident ground of being within itself and in its thinking—into the equally self-evident experience of being conditioned by the external world, all within the framework of a cogent ontology?[8]

This question would become central to Holz’s theory of reflection (Widerspiegelungstheorie). In his (second) lecture on Lukács, Holz conceptualises history both as the objectivity of human reality and as the universal concept of the individual. This figure of thought would also be systematised in his theory of reflection, taking up Lukács’s formulations of the philosophical concept of history—while simultaneously exposing their limitations and overcoming them. Lukács’s historical materialism sketches a plausible outline of the general course of history. Yet one may rightly ask: where is the place of human creativity in this process? How do human beings acquire the power to intervene in a history shaped by its overarching tendencies? How much room for manoeuvre do they have? And what is the basis of this leeway, which necessarily stems from the universal?[9]

These are the fundamental questions that lead to the development of a dialectical-materialist philosophy. According to Holz, they can only be answered through engagement with classical philosophy. It is for this reason that the third Girona lecture is dedicated to the influence of Leibniz on Holz’s thinking. At the outset of this lecture, Holz stresses that ‘the Marxist (has to) search for the substantiation of materialism in a world model that depicts the relationship between object and subject, being and consciousness, in a logically convincing manner and in accordance with experience within praxis’.[10] That such a substantiation is necessary for the Marxist does not imply that it has been commonly pursued within Marxist thought. On the contrary, Holz is arguably the first Marxist thinker to explicitly take on this task. Nor is such self-substantiation characteristic of classical philosophical materialism. Materialist positions, Holz notes, typically appear as posited presuppositions rather than as grounded outcomes of philosophical argumentation. Ernst Bloch had good reason, therefore, to speak of the ‘problem of materialism’ [Materialismusproblem]: unlike idealism, materialism does not enjoy the royal road of a self-grounding, consciousness-immanent foundation.[11] The theory of reflection represents an attempt to confront this difficulty by exploring the possibility of grounding materialism in a structure whereby material relations manifest themselves in consciousness. In so doing, it seeks to mediate between the ontological priority of being and the logical primacy of thought.

Holz arrives at such a model through his engagement with Leibniz. This engagement provides the conceptual basis for his effort to establish a foundation for materialist dialectics. At the core of this effort are two categories: totality, understood as the relational unity of individuals conceived as an open order; and possibility, understood as the openness of the real world to movement and change. ‘On the one hand, it is the category world that outlines the totality and unity of all being; on the other hand, it is the category possibility which designates that the real world is open to motion and change, that is, to a not-yet-real’.[12] These systematic insights, gained through Leibniz, resonate with what Holz calls the ‘impulse of Bloch’ in contemporary philosophy, as explored in the fourth Girona lecture. Bloch’s central idea, Holz argues, is to combine the concept of the world as totality with its processual openness and incompleteness, all within a systematic unity. ‘Real is not only what factually exists, i.e. what “the case is”, but also what is possible’.[13]

Bloch serves as a paradigmatic case of system-oriented philosophising and provides a form of historical legitimation for it. ‘Through Bloch’s philosophy, we encounter perennial problems of philosophical thought in contemporary guise. [Departing] from the immediacy of the realisation of philosophy in political praxis, Marxism is mediated again with the philosophical movement of thought from which it originated. Bloch’s philosophy compels us to consider and understand Marx in the light of Aristotle, Leibniz and Hegel. It was Bloch’s great merit to have drawn attention to the fact that Marxism must not evade the metaphysical question of the system character of the world…’.[14]

Yet this legitimacy must be earned through systematic grounding—this is the claim of the theory of reflection [Widerspiegelungstheorie]. The ‘model of a universal system of reflection’ [Entwurf eines universellen Reflexionssystems] becomes the subject of the fifth Girona lecture and is elaborated further in the subsequent ones. We may now turn to show how Holz’s later systematic works relate to his reconstruction of philosophy’s basic statements.

Philosophy—regardless of its ideological provenance—is a commitment to the rational grounding and validation of its claims about the world. What distinguishes philosophy from the specialised sciences, which are concerned with discrete sectors of reality, is its reflexive mode of theorising: philosophy aims to develop a concept of the totality of reality by means of foundational insights [Grundgedanken]. This grounding must, by necessity, begin with thought, since the foundation of thought can only be undertaken by and through thought itself. Yet this starting point seems to structurally privilege idealism. Dialectical-materialist philosophy is thereby confronted with the challenge of explaining how the material relations it presupposes can be grounded in thought. This is once again the problem to which Bloch referred when he spoke of the ‘problem of materialism’: unlike Cartesian traditions of self-grounding consciousness, materialist philosophy faces an exacerbated foundational difficulty—one that must be addressed if dialectical materialism is to satisfy the demands of philosophical justification. Since dialectical materialism cannot justify reality on the basis of thought alone—a feat that Hegel had attempted within the idealist tradition—it must instead secure the connection between being and thought in such a way that material relations can manifest themselves in and through thought.

Holz’s theory of reflection must be understood against this backdrop of philosophical foundation. It is an attempt to take seriously the challenge of grounding materialism within a dialectical-philosophical framework. As he writes: ‘The origin and the place of philosophy is within the philosophising subject that ascertains its relation to the world. The particular position of the subject toward objectivity is determined by thought. Therefore, thought itself becomes an object of thought and thus appears within philosophical thought as reflected reality. (That Descartes realised this fact proves his significance for modern philosophy.) From the outset, this means that thoughts are the reality with which philosophy is concerned—the world as will and representation. However, if thoughts are understood as mirror images of material objects and relations outside themselves (i.e., mirroring as a real relationship between real beings, and thoughts as the function of these relations), then the ontological right of primacy of the world is reinstated, and the inversion is revealed as a necessary illusion [Schein]—a mirror illusion in which the virtual appears as the primary and real’.[15] Holz’s theory of reflection is thus an effort to establish the priority of material relations upon the apparent primacy of thought.

Marxism, as it developed in the 19th century, incorporated the anti-metaphysical impulse of the post-Kantian era. Against this backdrop, it may seem provocative—or even misleading—when a Marxist philosopher explicitly aligns himself with the entire history of metaphysics and integrates this alignment into the project of founding materialist dialectics through the inheritance of traditional metaphysical questions. Since the publication of his major systematic work Weltentwurf und Reflexion (World Model and Reflection), Holz continued this ambitious trajectory with other works, including his multi-volume opus on dialectics. His Problemgeschichte der Dialektik von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart (The Problem History of Dialectics from Antiquity to the Present) does more than trace the history of dialectical thought—it reconstructs it from a systematic perspective. In Holz’s view, the history of philosophy is not merely a history of ideas but a history of problems, understood as the pre-history of systematic formulations. Thus, his engagement with the philosophical tradition serves the purpose of developing his own systematic model.

Holz’s focus on problems in the history of philosophy—especially those tied to theoretical dialectics—underscores his central aim: to lay the foundation for materialist dialectics within the horizon of classical philosophy, all while grappling with the internal difficulties of philosophical materialism. These difficulties come into sharper relief in his final major work, the three-volume Aufhebung und Verwirklichung der Philosophie (Sublation and Realisation of Philosophy).[16] After reconstructing the development of dialectics from Hegel to Marx in the first volume, and elucidating the theoretical concepts of the classics of the Third International in the second, Holz culminates the third volume with an ambitious proposal: the foundation of a materialist-dialectical theory of categories. Such a philosopher can hardly be seen as believing that philosophy will simply sublate and abolish itself in an undialectical manner. Nor does he assume that reconstructing the history of dialectical theory suffices to establish its foundation. Rather, Holz formulates this foundation as a still-unrealised desideratum and advances the theory of reflection as a possible model for the philosophical grounding of Marxism.

This proposition is central for understanding Holz’s significance for Marxist theory. As he puts it:

Dialectics, proceeding to be the heir of metaphysics, undertakes a perspectival change. Also, dialectics needs models of the world to set out the operational framework of active humans, to enable orientations, to amplify the reality-content of meanings, to answer sensible questions. However, dialectics cannot adopt a model of the world like an object vis-à-vis thought. The world is not an ‘object’, but a field of activity in which the thinking human is embedded as a part and moment of it. Humans not only have the world in front of them, but also around them. The world does not show and structure itself according to properties, but according to meaning.[17]

Humans are in the world and can form a concept of the world only from this condition of being-in, that is, from their perspectival relation and horizon. Metaphysical modelling, in this context, becomes an effort to determine this relation of reflection—the relation of being that arises from the human’s embeddedness in the world.

To grasp Holz’s significance for grounding materialist dialectics, one must carefully attend to the specificities of his conception. Central to his approach is a decisive break with any one-sided orientation—be it critical or affirmative—and a conception of dialectics not merely as method, but, drawing on Leibniz, as an ontological structural model of real universal interconnection. In Leibniz’s monadology, this interconnectedness appears as a relational plurality of individual substances, each manifesting the whole from its own perspectival standpoint.[18]

This rationale underlies Holz’s model of Widerspiegelung (reflection), which he elaborates not as an epistemological notion—i.e. the reproduction of reality in the mind, as commonly found in Marxist discourse—but as an ontological relation. Spiegelung (mirroring), for Holz, denotes the structural model of a materially grounded and reflexive whole: a real relation between finite being and infinite totality. The theory of reflection is thus both an ontology of universal relationality and—since this relationality appears as conditioned and reflected—a regional ontology of subjectivity.

This locates the theory of reflection at the intersection of material being and subjectivity: the subject, from the outset, exists within a material relation that presupposes the existence of its other—its external reality—in order to become capable of reflection. Subjectivity is therefore not an isolated or unconditioned capacity but one that is embedded within and determined by being. It is compelled to reflect being perspectivally, from within.

Holz conceives of subjectivity as reflection of reflection—as a relation that returns to itself within being, as one moment among others in the structure of being. This relation is asymmetric: it involves a reflexive moment that mirrors material relations. This dual character—of structural totality and objective transcendentality—was already present in Holz’s early writings.[19] Holz’s concept of Widerspiegelung should not be seen as an epistemological framework that passively duplicates reality, but as a model of ontological relation: the mirror, formally, is simply one object among others, but with the distinctive property of containing the image of another.

In this, the mirror does not arbitrarily represent, but re-presents a determined relationality. Mirroring presupposes the presence of the other—without the other, the mirror ceases to function as such. The mirrored image is not a mere duplication; it embodies the perspectival standpoint from which the object is mirrored. Thus, in its formal-structural characteristics, the mirror becomes a necessary metaphor for dialectical ontology—one that determines all being as being-in-relation, where each entity is what it is only in relation to another.

Crucially, the mirror also gestures toward a model of materialist dialectics: it does not merely depict the relation between being and thought abstractly, but reveals this as a material relation—one in which the ideal appears immanently, within the virtual image. If we heuristically treat subjectivity as analogous to the mirror, and consciousness to mirroring, we arrive at the concept of objective transcendentality: the subject, far from being placeless and unconditioned (as in classical idealism), is situated within being, and serves as the medium through which material relations appear.

As such, mirroring offers a viable structural model for materialist dialectics. It not only captures the general relation between being and thought but also specifies this relation as materially grounded. The entanglement of subjectivity and objectivity within the reflection-relation means that subjectivity is no longer an external or abstract observer but a reflexive moment within materiality itself. It reflects the world from a specific perspective, always embedded in and mediated by material conditions.

The structure of mirroring thereby demystifies the illusion (Schein) of consciousness’s priority, revealing instead that being is the condition for consciousness, which in turn mediates the appearance of material relations. Holz articulates this insight in his Girona lecture:

In this sense the mirror-relation as such is a material relation between material objects (the mirrored [object] and the mirror), from which the ‘immaterial’ phenomenon of the mirror image originates, which in turn cannot exist without a material carrier, namely the mirroring object (the mirror). The theory of reflection thus expresses the unity of the world in its materiality…[20]

Holz thus extends the mirror-theoretical conception of subjectivity—indispensable to any emancipatory dialectics—beyond epistemology toward a theory of objective activity. If mirroring is a material relation becoming conscious of itself, even in ideational contents, then it becomes possible to represent human practical and even natural relations within it as a structural model.

This surpassing of the epistemological paradigm was already anticipated in Marx’s critique of Feuerbach. As Holz puts it:

Marx worked out the reorientation towards the historical foundation of non-philosophical premises for philosophising without abandoning the base of the modern thought experience, through a structurally inconspicuous but substantial shift in determining the relation of humans and the world. Contra Feuerbach, who precedes thought with sensuousness as being-giving, Marx precedes apperception with “objective activity”.[21]

To take up this insight, subjectivity is no longer conceived merely as epistemological relation but as practical relation. Beyond reflecting the world, the subject becomes embedded in and co-constitutive of material relations—its consciousness an expression of the very structure it mirrors.

This notion of the mutual encompassing of the material and the ideal enables Holz to ground the theory-practice relation—essential to Marxism—within dialectics. At the end of the third volume of Aufhebung und Verwirklichung der Philosophie (Sublation and Realisation of Philosophy), Holz reflects on Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach:

His (Marx’s, J.Z.) concern was that philosophy should not remain [merely] a kingdom of concepts—which it is and always must be—independent of praxis, but that it must become a moment of praxis. Not theoria cum praxis, as Leibniz chose for the motto of his scientific society—where cum designates a conjunction that preserves distinction—but theoria qua praxis, expressing unity within difference. That is, not a binary but a dialectical relation.[22]

Theory as praxis: to conceptualise a dialectical relation between theory and praxis means neither substituting praxis for theory nor dissolving theory into praxis. Rather, it means that theory influences practice, and that praxis, under specific historical conditions, generates the need for theoretical reconsideration. In other words, in the sublation of theory through the process of its realisation, theory preserves itself as a constitutive moment of praxis. One of Holz’s key achievements lies in his dialectical reconciliation of theory and praxis—a disjunction that Marx criticises in the eleventh thesis on Feuerbach. Holz resolves this tension philosophically by positing both terms in a necessary dialectical relation, which he defines through the logical figure of the overarching general:

We view the eleventh thesis on Feuerbach in the context of the binomial ‘sublation and realisation of philosophy’. ‘You cannot sublate philosophy without realising it. If the two processes are to be understood as one, then this means: sublation is contained within realisation, and realisation within sublation. This is a parallelism in which both sides encompass one another.[23]

Without this dialectical figure—of reciprocal encompassing—it is not possible to comprehend the theory-practice relation in its necessary, non-contingent form. Philosophy preserves itself in the very process of its realisation; it must therefore be established as a dialectical-materialist philosophy that understands itself as a moment of praxis. Significantly, in his final work—after reconstructing the theories of Hegel, Marx, and the Marxist classics of the Third International—Holz develops a theory of categories that articulates the theory-practice relation. In doing so, he underscores the need to ground dialectical-materialist philosophy systematically.

Holz is critical of his own tradition in asserting that the sublation and realisation of philosophy does not entail the disappearance of philosophy. This is a crucial insight. Holz’s reflexive materialism is committed to a perennial philosophy—to grounding materialist dialectics through philosophy understood in the breadth and depth of its historical development. In today’s Marxism, this makes Holz a singularly creative thinker: his engagement with the problem-history of metaphysics signals a commitment to a substantive concept of philosophy which, as he shows, is not in contradiction with the eleventh thesis on Feuerbach—even if it has often been read as such in the wake of the abolition metaphor (reading Aufhebung in merely negative terms) and the enthusiasm for ‘realisation’.

References

Bloch, Ernst (1972): Das Materialismusproblem, seine Geschichte und Substanz. Frankfurt/M.

Hahn, Erich/Silvia Holz-Markun (Hgg., 2008): Die Lust am Widerspruch. Theorie der Dialektik – Dialektik der Theorie. Symposium aus Anlass des 80. Geburtstages von Hans Heinz Holz. Berlin

Holz, Hans Heinz (1996/97): Philosophische Theorie der bildenden Künste. Drei Bände. Bielefeld

Holz, Hans Heinz (2003): Widerspiegelung. Bibliothek dialektischer Grundbegriffe 6. Bielefeld

Holz, Hans Heinz (2005): Weltentwurf und Reflexion. Versuch einer Grundlegung der Dialektik. Stuttgart-Weimar.

Holz, Hans Heinz (2010/2011): Aufhebung und Verwirklichung der Philosophie. 3 Bde. Berlin.

Holz, Hans Heinz (2011): Dialektik. Problemgeschichte von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. 5 Bde. Darmstadt.

Holz, Hans Heinz (2013): Leibniz. Das Lebenswerk eines Universalgelehrten. Herausgegeben und mit einem Nachwort versehen von Jörg Zimmer. Darmstadt

Holz, Hans Heinz (2015): Freiheit und Vernunft. Mein philosophischer Weg nach 1945. Mit einem Vorwort von Jörg Zimmer. Bielefeld.

Holz, Hans Heinz (2017): Die Selbstinterpretation des Seins. Formale Untersuchungen zu einer aufschließenden Metapher. In: Ders.: Speculum Mundi. Schriften zur Theorie der Metapher, spekulativen Dialektik und Sprachphilosophie. Aus dem Nachlaß herausgegeben von Jörg Zimmer. Bielefeld.

Holz, Hans Heinz (2018): Die Sinnlichkeit der Vernunft. Letzte Gespräche. Herausgegeben von Martin Küpper, Vincent Malmede und Johannes Oehme. Berlin

Hubig, Christoph/ Jörg Zimmer (Hg., 2007): Unterschied und Widerspruch. Perspektiven auf das Werk von Hans Heinz Holz. Köln

Klenner, Hermann/ Domenico Losurdo, Jos Lensink/ Jeroen Bartels (Hgg., 1997): Repraesentatio Mundi. Festschrift zum 70. Geburtstag von Hans Heinz Holz. Köln

Zimmer, Jörg (2013): Hans Heinz Holz und das Problem der dialektisch-materialistischen Philosophie. In: Z. Zeitschrift marxistische Erneuerung 93: 138 – 148.

For further information, please see http://www.hansheinzholz.com/

[1] Holz 2018.

[2] Holz 1996/97.

[3] Holz 2005; Holz 2010.

[4] Holz 2011.

[5] Holz 2011.

[6] Holz 2013.

[7] Holz 2015.

[8] Holz 2015, p. 25.

[9] Holz 2015, p. 46.

[10] Holz 2015, p. 52.

[11] Bloch 1972.

[12] Holz 2015, p. 55.

[13] Holz 2015, 80.

[14] Holz 2015, p. 87.

[15] Holz 2005, p. 357.

[16] Holz 2010/2011.

[17] Holz 2005, p. 146.

[18] Holz 2013.

[19] Cf. Holz 2017.

[20] Holz 2015, p. 99.

[21] Holz 2005, pp. 366-7.

[22] Holz 2011, p. 339.

[23] Holz 2011, p. 345.