Polemics tend to thrive during periods of significant social upheaval. In West Germany during the 1960s, it became a communication strategy aimed at addressing the lingering effects of post-fascism. In contrast, the rise of polemics in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) was primarily driven by an enhanced self-confidence among the technical and scientific intelligentsia, which resulted from their integration into the planning and control centers of socialism.

In complex ways, new ideas began to emerge that simultaneously continued to assign ideological tasks to philosophy while demanding greater autonomy for it. Philosophy was expected to concentrate on socialism and to utilise its intellectual resources to shape this society. To achieve this, tools needed to be developed in close collaboration with other sciences communicated to the general public as quickly as possible.

The generation that navigated this balancing act was born in the 1920s and 1930s, having experienced war and destruction firsthand. They ultimately concluded that advocating for socialism was essential. During this period, philosophy became a productive force, providing momentum, fostering networks, and spreading ideas. In the GDR, the transformation of philosophy was closely linked to the philosophy of science, natural sciences, and logic.

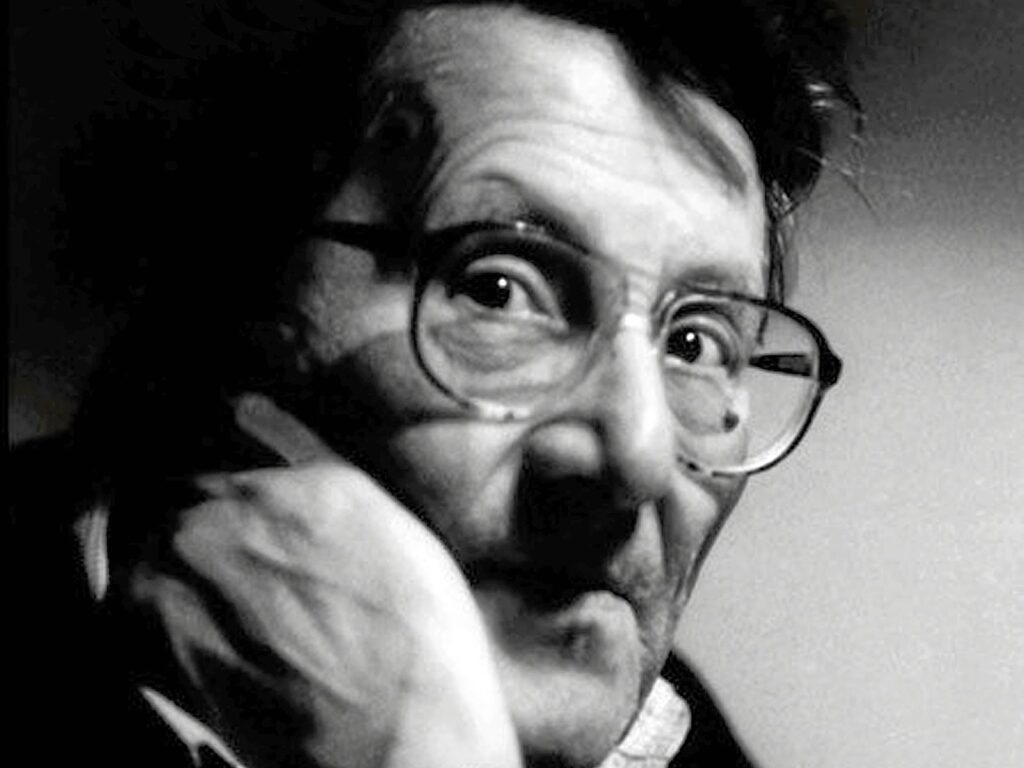

Among the notable products of these developments was Peter Ruben, born in 1933 and recently deceased. Ruben evolved into a prominent polemicist in philosophical Marxism but ultimately faced limitations within the political institutions of his time.

In 2022, the German publishing house Verlag am Park published a four-volume edition of Ruben’s philosophical writings[1], edited by Ulrich Hedtke (b. 1942) and Camilla Warnke (b. 1931). The volumes are organized thematically. While the first three compile his writings on philosophy and its relationship to physics, logic, mathematics, history, and economics, the fourth is dedicated to philosophy in the GDR and includes texts by Warnke. The edition provides insights into the historical circumstances of Ruben’s thinking as well as its continuities and ruptures. After its publication, this edition received significant attention in the German-speaking academic community, which is unusual for a philosopher from the GDR. The interest in Ruben’s work is not merely because he almost became a dissident and could therefore be categorised within the narrow, ideologically charged bracket of dogma and opposition. It also reflects the enduring relevance of his theses, as they address unresolved issues in both theory and practice.

Ruben’s Biography

After graduating from high school in 1952, Ruben served in the Kasernierte Volkspolizei (Barracked People’s Police) until 1955. In the same year, he joined the Socialist Unity Party (SED) and began studying philosophy with a minor in physics at Humboldt University of Berlin. However, he was forced to interrupt his studies in 1958 after being expelled from both the university and the SED due to his persistent challenges to party and cultural policies, as well as the official interpretation of the events of 1956 events in Poland and Hungary.

Following his expulsion, Ruben worked as an unskilled labourer on the construction of Schönefeld Airport. Despite these setbacks, he remained determined to resume his academic pursuits. Emigrating to West Germany was not an option for him, as he continued to identify as a communist. Additionally, his mother was engaged in the MEGA edition of Marx and Engels’s The German Ideology, while his brother was completing a doctorate in the Soviet Union. In 1961, Ruben was able to resume his studies and was readmitted to the SED in 1964.

Two significant educators influenced Ruben’s intellectual development: Klaus Zweiling (1900–1968) and Georg Klaus (1912–1974). Zweiling, trained in physics and mathematics, lectured on dialectical materialism, while Klaus, later a leading figure in cybernetics in the GDR, taught courses on formal logic. Both scholars explored the intersection of philosophy and the natural sciences, an inquiry that Ruben himself pursued. In 1969, he completed his doctorate under Hermann Ley (1911–1990) with a dissertation titled Mechanik und Dialektik. In this work, Ruben argued that criticism is an essential component of science. He challenged scientists from the socialist and the capitalist camps with intense polemics. For example, he charged Adam Schaff (1913–2006), a member of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, with advocating ‘pseudo-dialectics’[2]. Similarly, he criticised Karl Popper (1902–1994) for ‘capitulating to the aims of the philosophy of science,’[3] Ruben further contended that Popper struggled to provide a coherent definition of logic.

In his 1969 essay Problem und Begriff der Naturdialektik (not included in the large edition), Ruben articulated a key premise: ‘the meaning of a dialectics of nature stands and falls with the question of whether nature has a history.’ Ruben sharply criticised philosophers, as those in the tradition of Critical Theory, that rejected the notion of natural dialectics. He accused these thinkers, whom he labeled left-wing Hegelians, of ‘a desire for freedom of mankind but failing to understand how mankind can achieve freedom; hence their hostility to and ignorance of nature, which transforms the mere will to freedom into a hangover whenever knowledge does not rule the will. (…) There is no freedom from nature, only freedom within it. The illusion of freedom from nature is the essential content of the neo-Left Hegelian denial of the dialectics of nature—or this denial is itself that illusion of freedom from nature.’ For Ruben, the dialectics of nature was ‘essentially the theory of man as a natural being’. However, this did not imply a simplistic return to nature, as some ecological ideologues advocate in response to looming environmental crises. Instead, the dialectics of nature, according to Ruben, reveals that the appropriation of nature through the capitalist production relations in the present represents an ‘inhuman relationship’. Human existence, he argued, is only possible through social ownership of nature. As Ruben succinctly put it, ‘the appropriation of nature as social property is the content of the socialist revolution’.[4]

Through his polemical discussions, Ruben developed ideas that remain highly relevant today. His critiques were not limited to drawing boundaries; they also sought to establish a framework for theorising abstraction, labour, and contradiction. Ruben advanced his concept through a series of essays in the 1960s and 1970s. He adopted an interdisciplinary approach, exploring the intersections and distinctions among physics, mathematics, logic, and dialectics. The 1970s were particularly productive for him, marked by a visiting professorship in Aarhus University and a subsequent position at the Central Institute for Philosophy at the Academy of Sciences in Berlin. These roles contributed significantly to the increasing recognition of his methodological innovations.

Bernhard Heidtmann (1938–2014), a member of the Socialist Unity Party of West Berlin (SEW) and co-editor of the journal Sozialistische Politik, became acquainted with Ruben through Warnke and appreciated his work. As a result, Ruben’s writings gained visibility within the communist movement in West Germany. Ruben also developed a close working relationship with the West Berlin Hegel Colloquium. This collaboration included notable figures such as Peter Furth (1930–2019), Wolfgang Lefèvre (b. 1941), and Peter Damerow (1939–2011). Together, they formed the initial staff of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, which was established in 1994. Their efforts also supported numerous scientists affected by the Abwicklung (dismantling) of GDR scientific institutions.

Philosophy and Mathematics

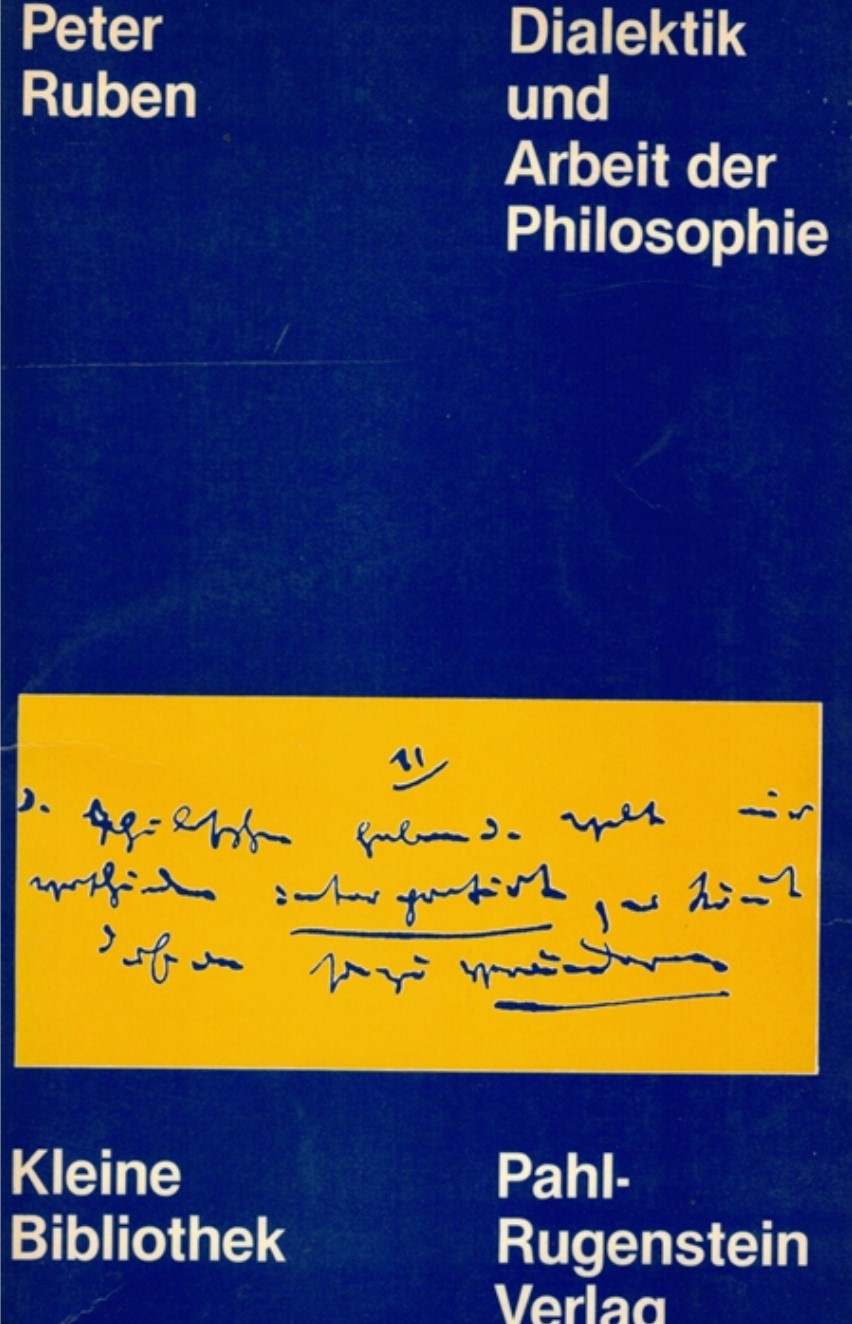

In 1979, Ruben articulated the essence of his approach in the brochure Philosophie und Mathematik. Drawing on Marx’s ideas, he defines every scientific activity as a form of ‘universal labour,’ with each specialised science representing an aspect of this concept. It is termed ‘labour’ because it involves a process in which individuals apply their skills to objective means and objects of labour. It is ‘universal’ because science produces ‘models determined by theories’.[5] These theoretical models reflect judgments and represent specific properties of natural objects that we seek to understand based on our needs.

With the rise of industrialisation under capitalism, these theories become essential to the production process of objects. In this context, it is not the human hand that directs the tool; instead, machines have integrated the tools into their operations. This shift leads to serial production, which is preceded by the programming of the machines. Reproducible sample drawings and models outline the work program for the machines.

The development of theories and models involves a process of abstraction. This does not mean simply eliminating aspects until only the essentials remain. Rather, to reach conclusions that enable us to make predictions and provide a theoretical foundation for our actions, we create categories, or genera, that represent populations. The individuals within a genus share common characteristics. By identifying distinguishing traits among parts of the population within a genus, we can form species. Establishing species helps crystallise characteristics that remain consistent under the same conditions.[6]

What may seem like philosophical thought is, in fact, part of everyday human practice, such as counting and measuring. For instance, when we go shopping, we might have bread rolls in our basket. We can count these rolls to determine their quantity. If we have ten rolls, it’s important to note that four of them may be priced differently than the other six. Simply stating that we have ten rolls tells us little about the total cost. When we shop, we often overlook the underlying nature of counting. In mathematics, however, we strive to understand the nature of counting to use it effectively in modeling. Descriptive and constructive mathematics are two approaches that help us grasp this concept. According to Ruben, however, neither approach delves deeply enough into the philosophical dialectics. He identifies a key contrast between abstract and concrete equations in understanding how we measure and count in reality—this contrast is informed by the value-form analysis developed by Marx. Mathematics tends to capture only abstract equations and, thus falling short of addressing the inherent dialectical contradictions.

According to Ruben, the philosophical significance of mathematics becomes clear when we consider its objectivity. In the GDR, various perspectives emerged regarding whether the specialised sciences reflect dialectical thought. Ruben’s position is clear: he describes separation and unification as aspects of counting that are fundamentally analytical and rooted in mathematics.[7] Mathematics , as a discipline, operates on the foundational assumption that contradictions do not exist within its logical framework. This assumption is necessary because contradictions would undermine consistency, making mathematical reasoning unreliable. According to Ruben, however, dialectics becomes relevant when the interconnectedness of things—obscured by abstraction—is consciously recognized. Thus, dialectics does not aim to solve mathematical problems; instead, it depends on abstractions while striving to criticise and transcend them. This implies that no scientific theory can conclusively determine whether reality is inherently dialectical; the question of dialectics remains a matter of philosophy.

Ruben asserts that both philosophy and mathematics maintain their independence. His insightful ideas remain pertinent, particularly in light of the continued mathematization of the sciences, which also prompts scientific inquiry into its political structuring.

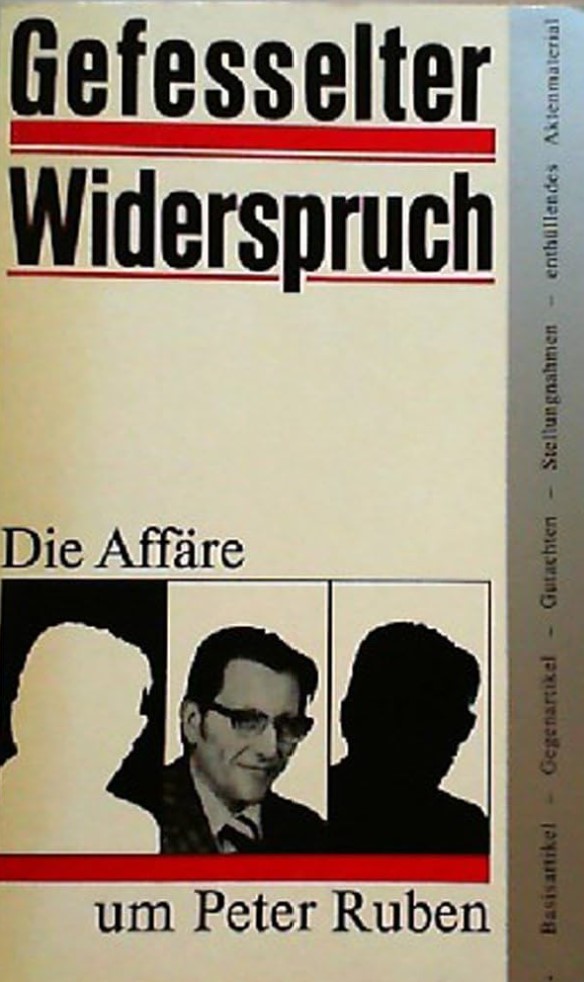

The ‘Ruben Affair’

The publication of the brochure in the Mathematische Schülerbücherei (Mathematical Student Library) was a result of growing political and scientific tensions at the Central Institute of Philosophy at the Academy of Sciences, which began to surface in the mid-1970s. Ruben accused his opponents, including Herbert Hörz (1933–2024) and John Erpenbeck (b. 1942) from the department Philosophical Questions in the Development of Science at the Academy of Sciences, of creating ‘confusion’[8]. Hörz and Erpenbeck raised concern that Ruben was establishing an insurmountable divide between the natural sciences and philosophy. This circumstance, marked by a mix of philosophical, political, and personal disagreements, ultimately led to the so-called Ruben Affair of 1980/81.[9]

The affair was triggered by an article co-written with economist Hans Wagner (1929–2012) on the socialist value form.[10] In this article, the two authors argued that ‘commodities are tied to the precondition of the existence of private property in the very general sense of the existence of different owners’[11] and called for a ‘value form of common exchange’[12]. In another article, Lenins Dialektik-Konzept und die materialistische Widerspruchslehre (Lenin’s Concept of Dialectics and the Materialist Theory of Contradiction), Ruben wrote of the ‘general validity of the value form for every historically occurring form of human labour!’[13] Critics saw this position as dangerous, fearing it would decouple the concept of ‘value form’ from the analysis of capital. The economist Klaus Müller, for instance, pointed out that Ruben misunderstood ‘value as the product of price and quantity.’[14]

In response to these controversies, a commission composed of members from the Academy of Sciences and external experts was established to evaluate Ruben and his colleagues. The expert reports ultimately concluded that Ruben’s approach was ‘revisionist’ and therefore contradicted SED policy. In an attempt to address the political disputes at an academic level, Ruben wrote sharp polemics against the expert opinions, but his efforts were in vain.[15]

As a result of the proceedings, Ruben was expelled from the party, subjected to publication restrictions, and transferred to another department. He remained employed at the Academy of Sciences largely due to protests from the German Communist Party (DKP), which warned against creating dissidents. Camilla Warnke, Peter Beurton (b. 1943), Bruno Hartmann, Hans-Christoph Rauh (b. 1939), and Ulrich Hedtke, all of whom were associated with Ruben, received severe reprimands and were either reassigned to new positions within the Academy of Sciences or transferred to other academic institutions.

The Revision of Marxism

For Ruben, the period of ‘inner exile’ began.[16] Step by step, he distanced himself from Marxism-Leninism and turned toward other theoretical influences such as Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) and Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936). He adopted Tönnies’ distinction between ‘community’ and ‘society’. While Marx argued that society is not made up of individuals but rather expresses the ‘sum of the relationships, relations (…) in which these individuals stand to one another’[17], Tönnies viewed ‘society’ as the legal connection between persons or communities (such as nations, poleis [city-states], etc.) that are in exchange with one another. From this point of view, communism appears to be an attempt to destroy society.[18]

The fall of the GDR had a catalysing effect on Ruben’s departure from Marxism. He was rehabilitated by the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS). He was appointed the director of the Central Institute for Philosophy of the Academy of Sciences in 1990, and became the president of the Berliner Debatte Initial association, as well as the co-founder of the journal of the same name. However, his career prospects in West Germany were limited. This was not only because the institutional philosophy landscape was thoroughly purged but also because he adhered to the natural dialectical premises of his thinking.

Without the GDR as a focal point, his writings after 1989 appear rather eclectic. Using his universal concept of abstraction, Ruben sought to revise fundamental aspects of Marxism, including alienation, class theory, and communism. He detached these concepts from traditional Marxism, attempting to fill the gaps he created with elements from other theories. This reconstruction, sometimes referred to as a ‘Marxist critique of Marxism,’[19] lacked a solid foundation. While the demise of historical socialism in Europe did not ‘in and of itself do away with Marxism,’ its end cannot be understood ‘as a practical decision on the acceptance of the validity of Marxist hypotheses.’[20] If one wishes to retain Marxism, its further development cannot consist of dissolving its core components.[21]

[1] It can be downloaded: https://www.peter-ruben.de/doks/downloads.html, last retrieved: December 17, 2024.

[2] Peter Ruben, ‘Mechanik und Dialektik,’ in Peter Ruben, Gesammelte philosophische Schriften, vol. 3, Berlin 2022, p. 195.

[3] Ibid., p. 75.

[4] https://www.peter-ruben.de/schriften/Natur/Ruben%20-%20Problem%20und%20Begriff%20der%20Naturdialektik%20.pdf last retrieved: 17th December 2024. The following quotations are from the page.

[5] Peter Ruben, Philosophie und Mathematik, Leipzig 1979, p. 73.

[6] Ibid., p. 49.

[7] Ibid., p. 113.

[8] Ibid., p. 45.

[9] See Hans-Christoph Rauh (ed.), Gefesselter Widerspruch. Die Affäre um Peter Ruben, Berlin 1991.

[10] See Peter Ruben/Hans Wagner, ‘Sozialistische Wertform und dialektischer Widerspruch,’ in Peter Ruben, Gesammelte philosophische Schriften, vol. 2, Berlin 2022, pp. 10–29.

[11] Ibid., p. 16.

[12] Ibid., p. 29.

[13] Peter Ruben, ‘Lenins Dialektik-Konzept und die materialistische Widerspruchslehre,’ in Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie 3 (1980), p. 304.

[14] Klaus Müller, ‘Letter to the editor,’ in junge Welt, April 17, 2023.

[15] See Peter Ruben: ‘Der Bericht kann nicht wahr sein!’, in Gesammelte philosophische Schriften, vol. 2, Berlin 2022, pp. 30–42.

[16] See Camilla Warnke: ‘Nicht vereinbar mit dem Marxismus-Leninismus!,’ in Gesammelte philosophische Schriften, vol. 4, Berlin 2022, p. 303.

[17] Karl Marx, ‘Ökonomische Manuskripte 1857/58’, in MEGA, II.1.1, Berlin 1976: p. 188.

[18] See Peter Ruben, ‘Von der Philosophie und dem deutschen Kommunismus,’ in Gesammelte philosophische Schriften, vol. 4, Berlin 2022, pp. 103–139.

[19] Peter Ruben, ‘Ist die Arbeitskraft eine Ware?,’ in Gesammelte philosophische Schriften, vol. 2, Berlin 2022, p. 291.

[20] Ibid., p. 290.

[21] This article is the revised translated version of ‘Dialektik fürs Kapitalozän. Zum Tod des Wissenschaftsphilosophen Peter Ruben (Dialectic for the Capitalocene. On the Death of the Philosopher of Science Peter Ruben)’ (Junge Welt, 24 October 2024) and ‘Philosophie als strenge Wissenschaft. Zur Ausgabe der “Gesammelten philosophischen Schriften” von Peter Ruben (Philosophy as a Strict Science. On the Edition of the “Collected Philosophical Writings” by Peter Ruben)’ (Junge Welt, 8 April 2023)..

Cover photo by Camilla Elle