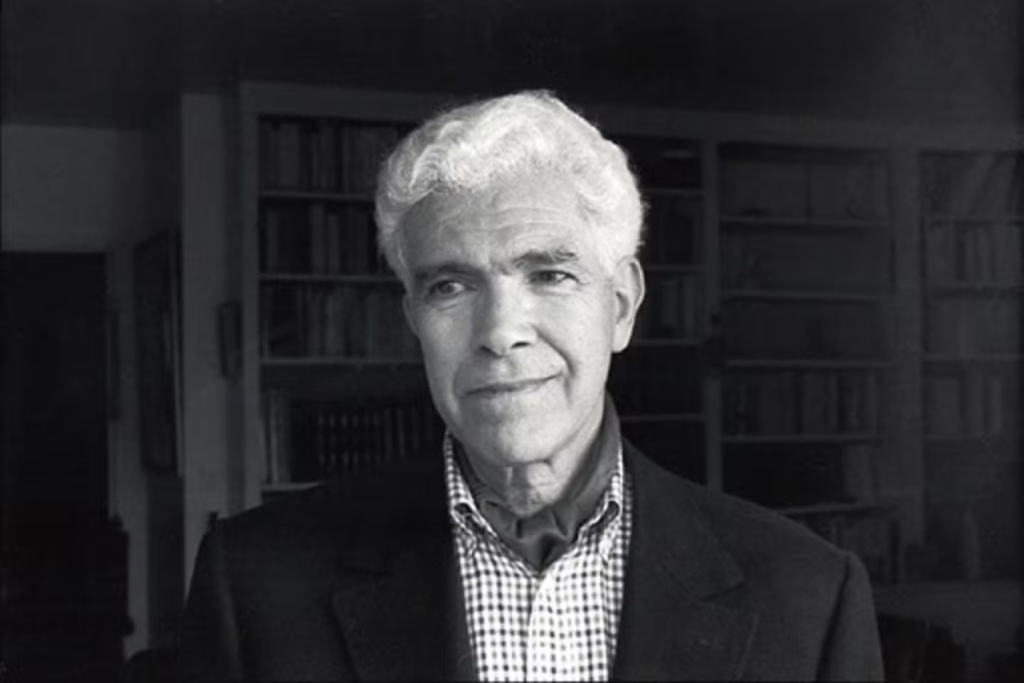

On 1 January 2026 Algerian anticolonial militant and historian Mohammed Harbi passed away, aged 92. Describing himself as a ‘Marxist in a nationalist organisation’, Harbi was a militant in the Algerian Front de libération nationale (FLN) during the independence struggle between 1954 and 1962 and the early years of independence. Arrested after the 1965 coup led by Houari Boumédiène, Harbi became a fierce critic of the regime. While in French exile since 1973, he became a leading historian of the Algerian struggle and the FLN. His work combined an insider’s view, theoretical sophistication and the rigour of the historian.

Born in June 1933 in well-off family that appreciated intellectual talent, Harbi had a ‘privileged childhood’. Harbi became politically active at a young age. In the late forties, he joined the anticolonial MTLD (Mouvement pour le Triomphe des Libertés Démocratiques) of Messali Hadj, describing his position as supporting independence and armed struggle. As a high-school student, Harbi had as one his teachers Pierre Souyri, a former résistant and a member of the heterodox Marxist group Socialisme ou Barbarie (SouB); ‘it was Pierre Souyri’s lectures that awakened my interest in Marxism. For many of us, he was, without even realising it, a reference point.’[1]

SouB had originated in the Trotskyist movement but had come to adopt positions that were close to those of the council-communist left. A central question for the group was that of bureaucracy. In The Revolution Betrayed, Trotsky had analysed the Soviet bureaucracy as a materially privileged stratum ruling over a ‘degenerated workers’ state’, a result of the isolation of the Soviet Union and the underdeveloped nature of its society. SouB, rather, saw the root of bureaucracy in the division of labour and the concomitant hierarchical relations that in its view characterised capitalism. The Soviet Union as well as China were, in this analysis, capitalist societies, although of a peculiar ‘bureaucratic capitalist’ type. When Harbi later would analyse the character of the FLN and of the one-party state that it had produced, similar concepts would be present. Harbi focused on how specific elite groups used organisational and ideological means to impose their rule. He sought to explain Algerian history politically, rather than adopting vague notions of ‘culture’ as an explanation.

After joining the FLN, Harbi became a key figure in its contacts with the European radical left, trying to organise political and practical support for the Algerian struggle. Harbi’s familiarity with Marxism and the debates among the dissident, non-Stalinist Left proved to be helpful, as the mainstream of the workers’ movement, both in its reformist and Stalinist incarnations, refused to aid the Algerian struggle or even opposed it. Notable among Harbi’s collaborators was Michel ‘Pablo’ Raptis, at the time a leading a member of the Fourth International.

Harbi saw the FLN as an essential tool to achieve Algerian independence but was aware of the limitations of its revolutionary populism. The FLN adapted its presentation according to its audience. When facing the international Left, the movement presented a democratic, progressive face and used Marxisant language. But, in its propaganda directed at the Algerian homefront, the movement was more inclined to use religious and traditional motifs. This tendency to stress the Arab and Islamic nature of the nation it sought to liberate from French colonialism meant marginalising the country’s ethnic and religious minorities.

The eruption of the armed struggle in 1954, Harbi wrote, marked a decisive change in the independence struggle; ‘the direct involvement of peasants in the struggle marked a new stage in the Algerian revolution. It took place under the leadership of the populists of the FLN’. The old elites who had previously dominated the struggle were pushed aside as ‘the village replaced the city’.[2] In the FLN, this populist current had imposed its hegemony over the other factions by all means available, including force. The existence of class divides in Algerian society was denied by declaring the indivisible unity of the Algerian nation. Unable to claim legitimacy as representatives of a class, the populist leaders instead used political mythology. Harbi developed this analysis in books such as his 1980 FLN, mirage et réalité, which was promptly banned in Algeria.

Already during his years as a FLN militant, Harbi’s differences with those who had more sanguine view of the organisation like Frantz Fanon became clear. Harbi recalled a discussion with Fanon and another comrade who had expressed their joy that the leadership had declared that national and social liberation were one whole and that the peasantry was the leading force in the revolution. Harbi told them they ‘were living in a fantasy world and projecting their political desires and strategic considerations onto a rural world the sociological nature of which they were concealing from themselves’; ‘Fanon made a meaningful grimace that showed how little interest he had in what he perceived to come from an orthodox Marxism.’[3] The notion that, because peasants made up the mass of the revolutionary fighters the revolution would be a peasant one, ignored the crucial issues of the nature of the political leadership and its programme. Fanon had what Harbi called ‘a spontaneist conception of revolution’.[4]

When, after years of intense struggle and sacrifice, Algerian independence was won, Harbi and others continued to work for a socialist orientation. Its 1962 Tripoli programme, that Harbi helped to draft, declared ‘socialism’ to be the FLN’s goal. As part of the FLN’s left wing, and together with international supporters of the Algerian revolution like Pablo and the Egyptian Lotfallah Soliman, Harbi put forward plans for a socialism based on workers’ control which would begin by socialising enterprises abandoned by colonists. In discussions with Algerian president Ben Bella, Harbi attempted to persuade him to abandon single-party rule by the FLN. Such a form of rule would not allow the formation of alternative centres of powers, such as workers’ self-management, all the more because the new government had basically taken over ‘the apparatus left behind by colonialism and this apparatus was completely opposed to self-management’.[5] But the 1965 coup by Houari Boumédiène meant the final coming to power of a FLN faction based on the army and bureaucracy. The FLN’s left wing was purged, and its international supporters expelled.[6]

Attempts to organise resistance against the coup failed and Harbi was arrested, sent without trial into internal exile and then put under house arrest. In 1973, he managed to escape using a false Turkish passport. Now in exile in France, Harbi reinvented himself as a historian of the FLN and the Algerian revolution. His death on the first day of 2026 means the passing of one of the last eyewitnesses of one of the great anticolonial struggles and the loss of an incisive historian.

Harbi has left an extensive legacy that, unfortunately, remains largely untranslated. Among his major works are Aux origines du FLN. Le populisme révolutionnaire en Algérie, Paris: Christian Bourgeois, 1975 and FLN, mirage et réalité. Des origines à la prise du pouvoir (1945-1962), originally published in 1980 and reissued in 2024 by Editions Syllepse. Together with Gilbert Meynier, he also edited a massive collection of documents, Le FLN: Documents et histoire, 1954-1962, Paris: Fayard, 2004. His own life was documented in his autobiography Une vie debout. Mémoires politiques 1945-1962, Paris: La Découverte, 2001, supplemented by a remarkable series of filmed interviews: https://www.youtube.com/@algeriememoirehistoirearch5081.

[1] Mohammed Harbi, Une vie debout. Mémoires politiques 1945-1962, Paris: La Découverte, p. 79. In his articles for the journal of the group, Pierre Souyri especially focused on Maoist China. These have recently been published as Pierre Souyri, Luttes de Classes en Chine Maoïste (1949-1967), Toulouse: Smolny, 2025.

[2] Mohammed Harbi, FLN, mirage et réalité. Des origines à la prise du pouvoir (1945-1962), Éditions Jeune Afrique, Paris, 1980, pp. 170-1.

[3] Harbi, Une vie debout, p. 297.

[4] Shatz, Adam, and Mohammed Harbi. “An Interview with Mohammed Harbi.” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques, vol. 28, no. 2, 2002, pp. 301–9, p. 305. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41299240.

[5] Mohammed Harbi, L’autogestion en Algérie. Une autre révolution? (1963-1965), Paris: Editions Syllepse, 2022, p. 24.

[6] See Catherine Simon, Algérie, les années pieds-rouges. Des rêves de l’indépendance au désenchantement (1962–1969), Paris: La Découverte, 2011.