It now struck him that nowhere in the modern world had so much crime gone unpunished as in Nazi Germany, with its extraordinary mixture of banality and bloodshed. Asked later why he chose Nazism rather than Fascism, Visconti said: “Because of the difference between tragedy and comedy. Fascism was a tragedy in many many cases…but as the perfect archetype of a given historical situation that leads to a certain type of criminality, Nazism seemed to me more exemplary… Nazism seems to me to reveal more about a historic reversal of values.”

Once he decided on the setting, Visconti realized that for years he had been unconsciously researching this very subject. Not only had he read many recent books about Hitler’s Germany, but also his passion for the theater had prompted him, as a young man, to visit the Weimar Republic during a period when theater history was made there. (…) he “retained precise recollections of the atmosphere of Germany in those days.” He meant originally to call his film Die Götterdämmerung (The Twilight of the Gods), because Hitler doted upon Wagner’s opera about the world of the Nibelungs, which ends in a blaze of death and destruction. (…)

Since industrialists were among Hitler’s first satraps, Visconti decided to make his fictitious family, the Essenbecks, the latest generation of a dynasty of steel magnates. He was accused later of having portrayed the Krupps but, in fact, his portrait of the imaginary Essenbecks contained details suggested by the lives of all the industrialists who supported Hitler—not merely the four-star Krupps, but also the Kirdorfs (coal), Thyssens (steel), Voeglers (steel), Schnitzlers (I.G.Farben chemical cartel), Rostergs and Diehns (potash), Schröders (bankers). Visconti’s reading about Nazi Germany had hitherto been desultory. Now it became systematic… Above all, he read and reread William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, of which he was to say, “…It really became our bible throughout the making of the film.”

Visconti wanted to show the beginnings of Nazism, the brief period when it might have been possible to stop Hitler.

(Monica Stirling, A Screen of Time, pp.191-93)

Following the murder of the von Essenbeck patriarch Joachim, Visconti shows the ensuing power struggle for control of the family’s massive steelworks as inextricably bound up with the struggle between the SS, the SA and the army generals, with the two major contenders within the family (Baroness Sophie [Ingrid Thulin], the widowed daughter-in-law of Joachim, whose lover Friedrich Bruchmann [Dirk Bogarde] is manager of the steel works, and Baron Konstantin, Joachim’s nephew and an SA officer) enlisting the support of one or other of those state rivals, and an SS officer Aschenbach manouvering to blackmail the heir apparent, Sophie’s son Martin [Helmut Berger] who has just killed a young Jewish girl he was sexually abusing. Konstantin is eliminated in a stunning sequence showing the Night of the Long Knives, during the bacchanalian debauchery of a thoroughly inebriated crowd of stormtroopers. He and his rowdies are machine-gunned by the SS as they fuck each other in states of half-stupor.

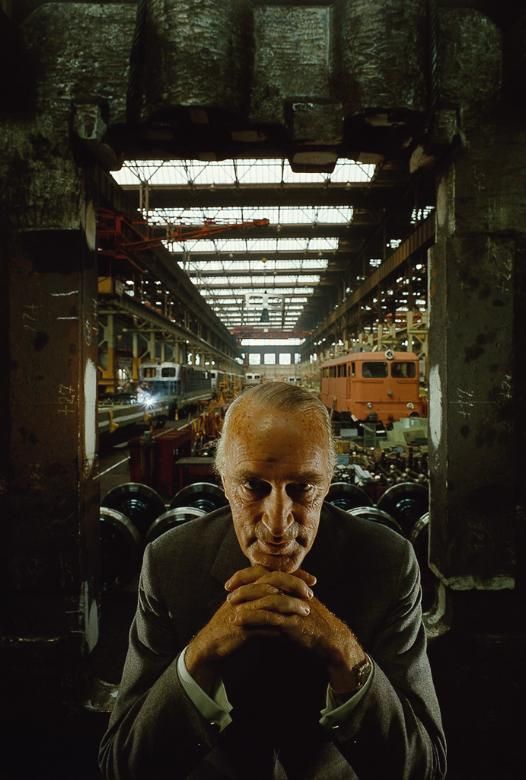

The most complex character by far, and a tribute to Visconti’s genius, was that of Martin, portrayed by the novice Helmut Berger, Visconti’s lover at the time (their relationship lasted from 1964 to 1976). The clash between Sophie and Martin fuses Oedipal themes with a naked power struggle for control of one of Germany’s biggest family enterprises. Visconti, of course, was forced to deny that the von Essenbecks were a cinematic replica of the Essen-based Krupp family, the country’s biggest steel magnates (next to Fritz Thyssen and the Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG), and Martin a portrayal of Alfried Krupp, the ruthless pro-Nazi businessman who took full control of the family firm when his father Gustav had a stroke in 1941. A scene in which Martin, wearing full SS uniform, orders Bruchmann not to be late for his wedding with Sophie and later even leads the way in their marriage procession could well be symbolic of the clash between family tycoons and a restless managerial class that never succeeding in creating Germany’s version of US-style managerial capitalism.

Fast forward beyond the film to 1951. The US High Commissioner for Germany John McCloy’s mass clemency towards Nazis convicted for war crimes has to count as one of the most shameful episodes of the Allies’ postwar settlement in Europe. Instigated in different ways by both McCarthy and Adenauer, it led to Krupp’s release from prison barely 2 years after his conviction (at Nuremberg) on a 12-year sentence as well as to restoring the bulk of his confiscated industrial assets. ‘A beaming Krupp strode out of Landsberg prison and celebrated a champagne brunch with his supporters’, writes Martin Lee in The Beast Reawakens. With Hitler’s full backing, Krupp had simply plundered territories occupied by the Nazis and made extensive use of slave labour. (The Krupp concern is said to have employed 100,000 slave laborers, recruited from the concentration camps, at a time when his ‘free’ employees were 278,000.) McCloy himself went back to Wall Street, becoming the chairman of Chase Manhattan.

(The photo is a portrait of Alfried Krupp by American photographer Arnold Newman, 1963. Newman’s style of photography came to be called ‘environmental portraiture’, hence the industrial context that surrounds Krupp. Unlike Martin in The Damned, Krupp emerges as a pure personification of capital.)

Jairus Banaji