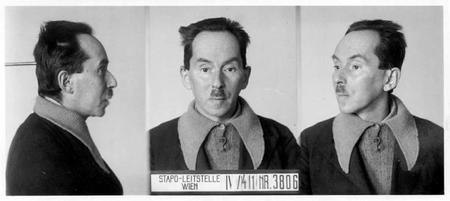

In May 1941, a new prisoner was brought into cell 44A of the police prison at Roßauer Lände, Vienna, Austria. A fellow-prisoner, Hans Landauer, a veteran of the Austrian Brigade in Spain, later remembered; ‘not yet fifty years old, he was already an old man. Short, red-hair – in as far as it was possible to say this of someone with so little hair left – the mouth almost without teeth, dressed in an ill-fitting suit, timid, indeed almost frightened…’ Soon his cellmates learned his name. He was Franz Koritschoner, an early member of the Communist Party of German-Austria and in the early years of the Party one of its most important leaders. Since 1930, he had lived in the Soviet Union where he had worked for the Red International of Labour Unions or Profintern. There, he was arrested as part of the ‘purges’ in 1936. A colleague of the Profintern who was arrested at the same time later remembered that Koritschoner was sentenced to three years of imprisonment. He appealed against the verdict, which was revised. Koritschoner was now sentenced to ten years in a labour camp. He spent years in penal colonies in the far North, suffering from hunger and extreme cold. He fell ill with scurvy and, at times, was forced to work as a gravedigger. After all, the mortality rate in the camps was very high. In April 1941, he was, together with around 40 others, handed over to the Gestapo in Lublin, Poland. After an interval of several weeks at Morzinplatz, the Vienna headquarters of the Gestapo, he arrived in the police prison at Roßauer Lände.

At first, his fellow inmates were distrustful of Koritschoner. Someone who had been imprisoned in Soviet penal colonies and subsequently deported surely was a traitor, an enemy of the Soviet Union. They were all the more surprised when, in private discussions, they heard from Koritschoner that, despite everting that had happened to him, he had not given up his faith in the Soviet Union. Hans Landauer writes:

During these conversations he again and gain emphasised that his arrest in the Soviet Union was the result of a mistake or sabotage. He never doubted the victory of the proletariat, of the party. In his case as well, one day the truth would come to light. The ‘current mistaken development’ would certainly be corrected and then one would recognise that those communists currently imprisoned in the Siberian camps were not traitors to the workers’ cause.

Koritschoner did not stay long in the Viennese police prison. Already in early June, he was transported to Auschwitz where, on 8 June, he was reported as having ‘passed away’. Two weeks later, the German armies marched into the Soviet Union.

Koritschoner’s fellow inmates could not know that, since the signing of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, the Soviet Union had deported hundreds of political emigrants, among them many loyal Communists, German and Austrian, into the hands of their worst enemy, National-Socialist Germany. They would also not hear about this for many years. The leaders of the Communist Party of Austria, the KPÖ, who, after the War, returned from exile in the Soviet Union remained silent about this and other crimes. For whatever reason, they would not reveal such crimes, not even to fellow party-members. After the 20th Congress of the CPSU, Koritschoner was ‘legally and politically’ rehabilitated, as the Historical Commission of the KPÖ put it in a history of the Party published in 1987 (without being able to specify when, where and on grounds of which articles of Soviet criminal code the sentencing of Koritschoner – to which the ‘rehabilitation’ referred—had taken place). It still took years after the 20th Congress before Koritschoner’s name was again mentioned in publications by the KPÖ. Of his life and his activity in the Party little is known. His work on ‘the Austrian workers’ movement during the war and revolution’, announced in a November 1928 issue of the Rote Fahne, never saw the light of day. This supposedly concerns a manuscript that is part of the private collection of the Viennese historian Herbert Steiner. Steiner published a small part of this manuscript which likely dates from 1924. The following brief sketch is partly based on this manuscript.

Koritschoner, born in 1892, came from a Jewish family of the grande bourgeoisie. Already during his time in the Gymnasium he joined the socialist youth movement and, as a student, he was an official of the Verbandes Jugendlicher Arbeiter, the Association of Young Workers. During those times, he also met the Russian Bolshevik Nicholai Bukharin, who until 1913, lived in exile in Vienna. Koritschoner later wrote that; ‘Bukharin came to Vienna in 1911 … He gained a strong personal influence over a part of the socialist academic youth. Bukharin’s educational work, which affected only a very small circle, would later bear fruit as it became the foundation of a small, but determined movement that would develop during the world war’.

By this Koritschoner referred to the young left-wing radicals who, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War would oppose the attitude of the Social-Democratic leadership that supported the War.

Contravening the earlier decisions of the Socialist International, at the outbreak of the War almost all the socialist parties of the warring countries came out in favour of ‘national defence’, the Austrian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party among them. Victor Adler spoke of a ‘situation of self-defence to defend the economic, legal and cultural spheres against the Tsarist desire for conquest’ whereas the social-democratic parties of the Entente claimed they were forced to confront Prussian militarism.

A numerically insignificant number of ‘leftist’ officials under leadership of Friedrich Adler was opposed to the attitude of the Austrian party leadership. Although they were honest opponents of the War, they in no case wanted to split party unity and refrained from all illegal agitation. The pacifist position that they defended in the party press and in speeches and resolutions at several party conferences found little support during the early years of the War. The despair over the merciless ‘staying the course’ of the own party as well as bitter hostility to the war policies of the government drove Friedrich Adler to his attack on the Austrian prime-minister Count Karl von Stürgkh in October 1916. The party leadership labelled his action that of a ‘madman’ and even Lenin criticised it as an ‘act of despair … isolated from the masses’, but the attack and even more the brave defence-speech of by Adler before the extraordinary court in May 1917 made a profound impression on the already war-weary masses. Its influence reached far beyond the borders of Austria and most of all had an impact on the youth of the warring countries.

The young Linksradikalen also welcomed the action of Friedrich Adler. Basing themselves on the Vienna-Ottakring (where Koritschoner was educational adviser) and Leopoldstadt branches of the Verbandes Jugendlicher Arbeiter, they had, from the beginning of the War, conducted lively, illegal propaganda. With primitive means, they produced anti-war leaflets for distribution – the first of which was a call against ‘the chauvinist campaign of the Arbeiter-Zeitung’. The leaflet attacked Friedrich Austerlitz’s infamous article of August 5, 1914, ‘On the Day of the German Nation’. The group quickly won support among members of the socialist high-school student organisation and the Vereinigung Sozialistische Studenten, the Association of Socialist Students. In the winter of 1915-16, a secret ‘Action-committee of the left-radicals’ was formed under leadership of Franz Koritschoner.

Inside the Socialist International, opponents of the War came stronger to the fore outside of Austria. In September 1915, opponents of the War coming from 11 countries met at a socialist conference in Zimmerwald, Switzerland. There were no participants from Austria, but the decisions of the conference encouraged the oppositional currents in Austrian Social Democracy. In April 1916, another international socialist conference took place, again in neutral Switzerland, in Kienthal. This conference was more heavily under the influence of the radical opponents of the War led by Lenin. Koritschoner was sent to this conference by the Action-Committee. Although he arrived late, he was able to meet Lenin and Bukharin. In Lenin’s letters from 1916, there are some references to his meeting with Koritschoner, who had aroused ‘great hopes’ in him.

As the War continued, the dissatisfaction among large popular layers in Austria became increasingly visible. Not only the horrific human death toll of the War, but also the misery caused by bad living conditions behind the front, resulting from insufficient supplies, the extension of the working day to 12 hours and the increasing pace of work in the militarily led arms-factories formed a fertile soil for agitation by anti-war activists.

The left-radicals showed a lively activity in the great mass-strike that erupted on 14 January 1918. Beginning in Wiener Neustadt, within a few days it encompassed hundreds of thousands of workers not only in Austria itself but also in Krakau, Brunn and Budapest. One of the triggers of the strike was the reduction by half of flour rations. But soon, the strike also had political goals. The Soviet government that had emerged from the October revolution of 1917 had immediately made a peace-proposal to the Central Powers. This evoked hopes among the peoples of the warring countries that the end of the War was near. In December, peace negotiations took place in Brest-Litovsk. However, these were temporarily broken off by the Soviet delegation on 12 January because of the enormous demands made by the Central Powers. Bitterness resulting from disappointed hopes for peace contribute to the outbreak and rapid spread of the strike. In illegal, mass-distributed leaflets, the left-radicals demanded an immediate cease-fire and the election of workers’ councils modelled on the Russian example.

Grudgingly, the Social-Democratic leadership engaged itself in the spontaneously erupted strike. It succeeded, although it took all its strength in convincing the workers to break off the strike. Otto Bauer wrote about this in his book Der österreichische Revolution: ‘in the stormy meetings before the end of the strike, the left-radicals carried out an intense agitation. This small group, led by Franz Koritschoner had … made connections with workers in the industrial area of Vienna Neustadt. Now, it opposed the decision to break of the strike … To them calling of the strike was pure treason.’ Bauer gives a list of reasons why the party leadership wished the strike to be a ‘great revolutionary action’, but ‘could not want’ the extension of the strike into a revolution; ‘the military position in the areas affected by the strike, the rejection of the strike by Czech workers, the millions in the German reserve army of labour’, and so on. The left-radicals refused to accept these arguments. Koritschoner wrote; ‘The capitulation was decided at a moment when the workers were capable of overthrowing the government and imposing an immediate peace. The Austrian government, lacking ammunition for the army, with a rebellious proletariat in its back and mutinous soldiers at the front, was shaken to its inner core – at that moment, the Social-Democratic leaders came to the rescue of the imperilled state’.

The strike was called off and the mass slaughter lasted for several long months more, until the collapse of the Central Powers in the autumn of 1918. After the strike, left-radical activists, among them Koritschoner, were arrested. They were not released until the end of October, when the monarchy was collapsing. On 12 November 1918, Austria became a republic.

On 3 November, the Kommunistische Partei Deutsch-Österreichs (as it called itself until 1920) was founded. The initiative for its foundation became from two small groups that were almost unknown to the general public and that had no links to significant layers of the working class. The ‘left-radicals’ that considered the foundation of the Party to be premature and hesitated.

Koritschoner reports that, around this time, there were meetings with Friedrich Adler, who attempted to convince the left-radicals not to join the Communist Party and offered to work together. But a unification did not take place.

About his considerations concerning joining the KPDÖ Koritschoner wrote: ‘objectively seen, the foundation of the Communist Party should be characterised as premature because it precluded the consolidation of a left-radical movement, while part of the revolutionary groups remained in the framework of Social Democracy and only a small fraction went over to the new party … while the ideas of the Russian Revolution, the idea of Soviets was deeply rooted in the consciousness of the workers, the idea of a Communist party remained alien to them.’

Despite their misgivings, the left-radicals joined the Communist Party in early December 1918, stating ‘We are joining the Communist Party of German-Austria, the only class struggle party that stands with the old socialist ideas’. With this, the Communist Party won a number of workers from the workplaces where the left-radicals since the January strike had some connections. It also meant that the Party was joined by organisers who were more capable than the original founders. Obviously, the latter realised this as, according to Koritschoner, to agreed that the left-radicals would take half of the seats in the party-leadership, be represented in the editorial board of the Party’s newspaper and be given the right to continue illegal work ‘by themselves’, and without oversight.

At the first party conference in February 1919 Koritschoner was elected to the party leadership. He would be a member for several years. During these years, he also represented the Austrian Party at the Congresses of the Communist International and the Communist Youth International as well as at meetings of the Executive Committee of the International. He was one of the best known and most effective speakers of the Party.

A part of the Austrian working population had expected that, from the collapse of the monarchy, a socialist republic would emerge. The birth of short-lived council republics in Hungary in March and in Munich in April 1919 strengthened such hopes. The membership of the Party increased from around 3,000 in early 1919 to 40,000 during summer that year. During the first republic, the Party would never again come close to this membership figure. But the Party did not succeed in penetrating the masses of industrial workers that remained loyal to Social Democracy. The new party found its members mostly among the unemployed and the disabled and veterans returning from the War. Those groups hit hardest by the post-war crisis. The radicalisation of these groups led to heavy clashes with the police on 17 April and 15 June 1919, resulting in several deaths and heavy injuries.

The defeat of the Hungarian council-republic pushed the Communist Party of Austria into a deep crisis. The hope that with mass-actions the Austrian workers could come to the aid of the Hungarian revolution proved to be illusory. Inside the Party, intense discussions regarding strategy and tactics took place. As the Party lacked a real political base, it was not able to test the correctness of different opinions in practice. Because of this, the discussions increasingly degenerated into fruitless bickering between individuals and groups. Little is known today about the real content of these confrontations; in party publications, they were dismissed as ‘unprincipled factional fights’. Koritschoner was involved in these conflicts at the side of his personal friend Karl Tomans.

In authoritarian fashion, the Communist International finally put an end to the conflicts inside the party leadership. A representative of the International made sure that in the autumn of 1923 the party leadership, which had been elected only months prior, was deposed and replaced by unelected officials. When, in 1924, at the Seventh Party Congress, again fierce confrontations took place, the International transferred leadership of the party to an ‘executive committee’. Not until the Eight Congress in 1925 was a new leadership, one that was approved by the International, elected. Since then, Koritschoner was no longer part of any of the leading bodies of the Party. He continued to speak at the congresses of the Party, write for its publications and, most of all, dedicated himself wholeheartedly to the education of the youth in the Party. Rosa Puhm, at the time an official of the Kommunistischen Jugendverbands wrote about this; ‘In those days I got to know the sympathetic comrade Franz Koritschoner. He worked with youth like us and for me was a kind of father figure’.

When Koritschoner dedicated himself to politics, he gave up his bourgeois existence. As a grandchild of one of the founders of the Länderbank, he had been director of one of its branches. That subsequently he lived in difficult conditions is confirmed by Lucien Laurat in his Le Parti communiste autrichien. ‘When I was in Moscow in 1924, 1925 and 1926’, he wrote, ‘I visited Bukharin more than once and pointed out to him the material needs of Koritschoner. After each time, Koritschoner would receive a letter asking him to write several well-paid articles for Pravda.’ It was also because of Bukharin that Koritschoner in 1929 or 1930 was called to Moscow to work for the Profintern.

Already during his last years in Vienna, Koritschoner had told friends that he thought that the policies of the Communist Parties were too strongly determined by the national and international interests of the Soviet Union. Such heretical statements – the veracity of which would be increasingly confirmed – likely contributed to his arrest and tragic end.

A young historian, close to the Communist Party, called Koritschoner ‘surely the most significant personality’ in the early history of the Party. One of its ‘most honest leaders, with a strong character … who would not let himself be dissuaded from his opinions’. This view is based on the judgment of people who had known Koritschoner personally. To do justice to his life and work, today, half a century after his death, access to both the archives of the Austrian Communist Party and the Soviet-Union is needed. When will this be possible?

Original publication in: Memorial. Österreichische Stalin-Opfer (Vienna, 1990).

Translation by Alex de Jong.