In his 2017 book De la Vertu, Jean-Luc Mélenchon attacks the corruption and immorality of contemporary politics.1 In support of his arguments he cites Colette Audry’s book Les militants et leurs morales [The Activists and their Moralities].2

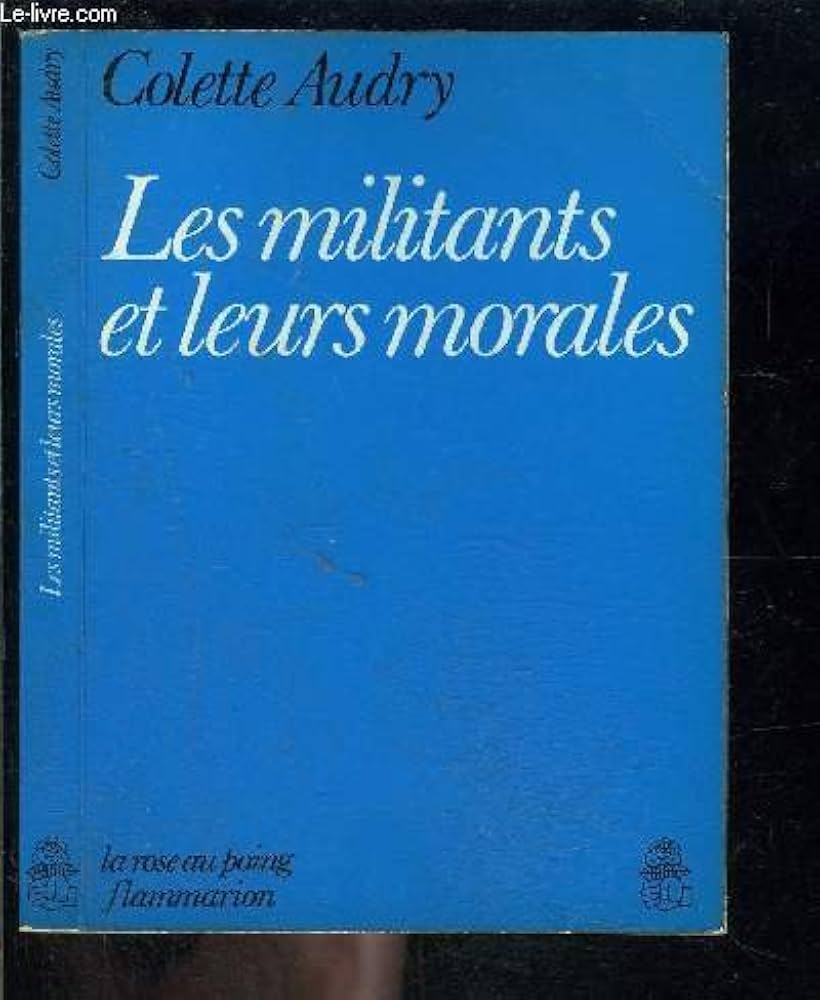

Audry is not a well-known name today, and only a few of her books are in print. (Mélenchon has promised to get a new edition of Les militants et leurs morales published.3) But she was a significant figure on the French Left in the mid-twentieth century, and she deserves to be remembered and read.

Audry was born in 1906, into a political milieu.4 Her great-uncle was Gaston Doumergue, a Radical politician who became President of the Republic in 1924; his period of office included the Rif War and repression in Indochina.

Her father had been active in the Socialist Party, but became a state official and eventually a préfet (the highest state functionary in a département).

Audry trained as a teacher, and in 1932 moved to Rouen, where she became active in the teachers’ trade union. Alongside her political and literary activities, she continued to work as a lycée teacher for most of her life until her retirement in 1965.

In Rouen, she met Paul Nizan, a friend of Sartre and a committed Communist, who introduced her to Simone de Beauvoir. She briefly considered joining the Communist Party, but read Trotsky’s My Life and became committed to the anti-Stalinist Left.

This was a dramatic period of French history, with some striking parallels to our own age. With Hitler’s accession to power in 1933, France had fascist regimes on two of its main frontiers. A right-wing riot in February 1934 brought down the government and raised genuine fears of a fascist take-over.

There were widespread demands for left unity. The Communist [PCF] and Socialist [SFIO] Parties united with the middle-class Radicals to form a “Popular Front”. In 1936, the Popular Front won an electoral majority, and a government was formed under Socialist leader Léon Blum. But, before Blum even took office, the rising expectations of workers led to a general strike of two million workers, many of them occupying their factories. It was this wave of direct action, rather than the Popular Front’s programme, which produced some real gains for workers, notably wage increases, trade-union rights in the workplace, a forty-hour week and two weeks paid holiday per year.

Audry became an active member of the SFIO in the early 1930s, attending meetings and selling the SFIO paper Le Populaire on the streets. Unlike the monolithic PCF, the SFIO allowed organised factions; Audry was a founder-member of the Gauche Révolutionnaire [Revolutionary Left] led by Marceau Pivert, which represented the most radical wing of the party.5 At the time of the 1936 strikes Pivert wrote a famous article proclaiming that “Everything Is Possible”.6 The Gauche Révolutionnaire did not confine itself to polemicising but organised against fascism, setting up the armed groups of the TPPS [Toujours Prêts Pour Servir: Always Ready to Serve], which drove the fascists out of working-class districts.7

Audry was also an active trade unionist and was already beginning to develop as a writer. She wrote for various left-wing publications, including La Révolution prolétarienne, (launched by Pierre Monatte after his expulsion from the PCF in 1924), as well as the left-wing trade-union paper L’École émancipée (notable among the contributors to this was Maurice Dommanget, a distinguished historian, who wrote on Babeuf and Blanqui; when Trotsky was exiled in France Dommanget found him accommodation). To help understand the Nazi threat, she wrote a study of Heidegger, showing the essentially fascist nature of his philosophy and anticipating arguments that would be developed ten years later.8

In 1936, too, the Spanish civil war broke out. Despite a previous agreement, Blum refused to send French arms to defend the Republic. Audry became a supporter of the POUM [Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista: Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification], which earned the enmity of the Communist Party for being anti-Stalinist revolutionary socialists. She visited Spain at the start of the war; she was a gifted linguist and helped to produce and distribute a French version of the POUM’s journal.

Audry was also a close friend and work-colleague of Simone de Beauvoir. In her memoirs, de Beauvoir described Audry as a Trotskyist. In fact, there is no evidence that she was ever a member of a Trotskyist organisation.9 (Trotsky was very critical of the POUM.10) But she was certainly familiar with Trotsky’s writings and ideas and was influenced by them. She was strongly critical of the way Stalinism was developing.

But she did not confine her activity to writing and party work. On occasion, she put her head on the line to pursue her principles. In 1939, Franco was victorious; half a million Republican refugees fled across the Pyrenees. They were not welcomed in France; the government, still based on the parliament elected on the Popular Front programme, herded them into horrific improvised camps on the French beaches.

Audry, with Daniel Guérin and other comrades, took a lorry across the Pyrenees to find the POUM leaders, who risked freezing to death or being murdered by Stalinists. Audry, as the daughter of a préfet, knew how such things worked and managed to obtain a document which got them through the frontier controls. They rescued five POUM leaders including Wilebaldo Solano.11 (When I met Solano, some fifty years later, he still remembered Audry with gratitude.)

In 1938, the Gauche Révolutionnaire was expelled from the rightward-moving SFIO and the members formed the PSOP [Parti Socialiste Ouvrier et Paysan: Workers’ and Peasants’ Socialist Party], which Audry rather unenthusiastically joined. She was opposed to the looming war with Germany and signed the Manifeste des femmes contre la guerre [Womens’ Manifesto Against War]. After the German occupation, she became involved in the Resistance and worked alongside Communists in the Grenoble area. In 1939, she married Robert Minder, and had a son, Jean-François (to whom Les militants et leurs morales is dedicated); they divorced in 1945.

Audry was already a close friend of Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. At the Liberation, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty founded a new journal, Les Temps modernes. Audry was immediately involved with the circle around the journal, writing regularly for it and becoming a member of the editorial team. Les Temps modernes aimed to be a journal of the independent Left, publishing such authors as Victor Serge and Richard Wright. (Audry wrote a very favourable review of Serge’s novel The Case of Comrade Tulayev.12) It published reports from the USA by Audry’s old comrade from the Gauche Révolutionnaire, Daniel Guérin; reports that were too critical of US racism for the right-wing press, but too sympathetic to American workers for the PCF.

In the early fifties, Sartre, for a few years, took a position close to the PCF. However, Les Temps modernes continued to publish material hostile to Stalinism. In 1953, the journal carried three highly critical articles by Marcel Péju on the show trial in Czechoslovakia in which the former secretary-general of the Communist Party, Slánský, was sentenced to death.13

In 1953, Audry wrote a sympathetic review of a book critical of Stalinism; she described PCF intellectuals as mindless transmitters of the official line and contrasted Lenin to contemporary Communists.14 This provoked a very hostile response from Jean Kanapa, one of the most servile of the intellectuals in the PCF leadership. Sartre was furious at this attack on his old friend, and temporarily suspended his alliance with the PCF to launch a sharp polemical reply.15 Kanapa was forced to make a rather grudging retraction.

In the mid 1950s, new currents began to emerge on the French Left; the rising in Hungary had produced a certain degree of opposition in the PCF, while many SFIO members were deeply hostile to their party’s support for the war in Algeria.

Audry was involved in the emerging New Left. She wrote for the journal Arguments, which aimed to develop a non-Stalinist Marxism.

She was hostile to the French war in Algeria, signing a statement calling for a negotiated peace.16 But she refused to sign the famous Manifesto of the 121 supported by Sartre and others, because she did not approve of advocating desertion from the army, believing that radicalised soldiers should stay in the army and organise opposition.17

The various left currents led to the foundation of the PSU [Parti Socialiste Unifié], of which Audry became a member in 1960; she stood several times as a candidate for the PSU in national and local elections.

In 1968, a wave of student demonstrations sparked off a general strike which repeated 1936 on a much bigger scale. Ten million workers struck. Audry supported the movement from the outset. One of the very first statements supporting the students – when the PCF was still complaining that working-class students were being prevented from sitting their examinations18 – was signed by Audry together with Sartre, de Beauvoir and Daniel Guérin.19

The period after 1968 saw a realignment of the French Left. The SFIO had never recovered from its losses during the Algerian War. The PCF, which had criticised the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, was slowly moving away from its former slavish loyalty to Moscow.

Now François Mitterrand proposed the launching of a new Socialist Party. Mitterrand was a careerist politician – during the Algerian War he had served as the so-called Minister of Justice and had ordered executions of liberation fighters in Algeria.20 Later, he had become an opponent of President de Gaulle. His aim was to launch a new party, with himself as leader, which would seek an alliance with the PCF and thereby win over Communist voters to support his party. (Previously, all other political parties had refused to make alliances with the PCF, even though it got some 20% of the vote.)

Audry joined the new party and became a member of its executive committee There is no evidence that she felt any enthusiasm for Mitterrand; it is noteworthy that, in Les militants et leurs morales, which was aimed at the members of the new party, the name Mitterrand occurs just once – in a footnote.

Her aim was to influence the new members of the organisation, especially the younger generation. One of the young activists whom she met and encouraged was none other than Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who never forgot her.21

Audry’s aim, in many ways, remained what it had been over forty years earlier in the Gauche Révolutionnaire, namely to contribute to the formation of a current of the Left that had broken with the negative features of both Stalinism and social democracy. Her aim was not to choose between them, but to go beyond them both.22

She was familiar with the history of the Russian Revolution, and frequently referred to Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolshevik Party, drawing out their positive features. But, unlike many Marxists, she did not quote them as authorities, but referred to their ideas as something that should be approached critically; there was much to be learned from them but they were not infallible.

Mitterrand was elected president in 1981 and brought the PCF into government. The results were disappointing; Mitterrand soon abandoned the more radical elements of his programme and moved to the right. It was amid the disillusion with his government that the Front National (precursor of the Rassemblement National) first began to take off. This must have been a disappointing time for Audry, and she devoted more of her time to literature than to politics. But she never abandoned the basic principles which had inspired her over six decades of socialist activity. She died in 1990.

Audry wrote prolifically throughout her life. She was the author of a number of novels, including the autobiographical La Statue, Derrière la baignoire, which tells of the life and death of a dog, and L’Héritage, a story of family conflict.23

Her 1956 play, Soledad, about revolutionaries in a South American dictatorship, was a success and was later made into a film Fruits amers (1967); her sister Jacqueline was a well-known film director. She also worked on film scripts, notably La Bataille du rail (1946), about sabotage by railway-workers during the German occupation.

She wrote two books about Sartre, Connaissance de Sartre and Sartre et la réalité humaine.24 Her historical essay Léon Blum ou la politique du juste,25 presented an argument also developed in Les militants et leurs morales. Her final book, Rien au-delà,26 published posthumously, was an exchange of letters with a Benedictine monk in the last years of her life.

Mélenchon is right to see the question of morality as central to Audry’s work. For her, politics was a matter of choices and values. She remained deeply marked by the experiences of the 1930s, when she was first involved in political activism – the threat of fascism, the possibilities aroused by the Popular Front and the deep-lying contradictions at its heart.

Audry was concerned to get away from the mechanical reductionist Marxism widespread on the Left. She and her fellow-activists in the Gauche Révolutionnaire recognised the need to understand the novelty of fascism and the new problems it posed for the Left. In the final paragraph of her 1934 article on Heidegger, Audry lamented the fact that mainstream Marxism had become obsessed with the economic and political, rather than giving a more complex materialist account of the totality of human culture,

In his study of fascism and capitalism, Daniel Guérin, while giving full importance to the economic factors which produced fascism, also argued that the Left often neglected the psychological appeal of fascism.27 Audry was doing something similar with her article on Heidegger and her attempt to understand the “tragic” nature of Nazi philosophy.

In Les militants et leurs morales, Audry cited Sartre – from Saint Genet – as saying that under capitalism morality was simultaneously inevitable and impossible [la morale est tout à la fois inévitable et impossible].28 Inevitable, because human beings are obliged to choose – in Sartre’s phrase “condemned to be free” [condamné à être libre]29 – and all choices are choices of values. But impossible because, in an unequal society divided by class, we cannot apply the same moral standards to the whole of society. Present privileges are based on the use of force in the past.

At the end of his major philosophical work L’Être et le néant, Sartre had promised a sequel dealing with moral questions.30 He never published that sequel, but his incomplete draft was published posthumously as Cahiers pour une morale.31 It is not impossible that Audry, who was very close to Sartre, had seen or discussed Sartre’s work from the 1940s.

In the Cahiers, Sartre quoted with admiration Trotsky’s Their Morals and Ours. He argued that the idea of a future socialist society was not something pregiven and known, but something to be created; hence, any end we arrive at will be the product of the means used to get there.

Audry had known Sartre since the 1930s; later she wrote two books about him. But she should not be seen merely as a disciple of Sartre. In the 1930s, Audry had developed an understanding of politics far beyond Sartre’s, and he learned a great deal from her (although he foolishly and perhaps facetiously used to argue that women should not be involved in politics32). Audry found the time to try and influence him.33

Audry’s concern with morality led her to confront a question which would become central for twentieth-century Marxism, the relation between exploitation and oppression. In particular, Audry was a pioneer feminist.

In 1936, women still did not have the vote in France. The parties of the Popular Front, fearing the influence of the Catholic Church on women, did not include the right to vote for women in their programme (although Blum did appoint three women ministers in his first government). It was the Vichy constitution that first gave French women the right to vote; only after the Liberation were they able to exercise that right.

In the 1930s, Audry was a close friend of Simone de Beauvoir, and often said to her that someone should write a book on the oppression of women.34 Audry never had time to write such a book, but she seems to have been the original inspiration for de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. When de Beauvoir published her book, she faced widespread criticism, including from the PCF and others on the Left.35 Audry defended her and published a review of reviews, examining the criticisms directed against her friend. She stressed the book’s relevance and expressed surprise that the Communist press had been so hostile when de Beauvoir had drawn heavily on Engels.36

Les militants et leurs morales was one of her last works, when she was interested in seeing the development of a new generation of activists in the Socialist Party. In it, she set out her argument that morality was central to political action, looking at the different concepts of morality held by Lenin and the Bolsheviks, Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg, and by social democrats, in particular Léon Blum.

The central theme of the book is to look at aspects of the history of the socialist movement and the way it has been affected by the problem of morality. In particular, she looks at the two major currents which have dominated the history of socialism in the twentieth century – Stalinism and reformist social-democracy.

A good deal of the book is devoted to the experience of Stalinism. She cites numerous examples of Stalinist activists and intellectuals and the ways in which, in various circumstances, they betrayed moral principles in acting as they did.

Audry makes quite clear her hostility to Stalinism, which she describes as “one of the most crushing and murderous tyrannies that history has ever experienced” [une des tyrannies les plus étouffantes et les plus meurtrières que l’histoire ait connues].37

But she also clearly demarcates herself from “anti-communism”. She does not accept any direct continuity between the Bolshevik Revolution and the emergence of Stalinism. On the contrary, she is often sympathetic in her treatment of Lenin and Trotsky, and, when she is critical of them, it is in quite different terms from her condemnation of Stalinism.

She is equally critical of the reformist social democracy which had dominated the pre-war SFIO, where she had had her first political experience. In particular, she looks at the experience of Léon Blum, whom she refers to as “Le Juste”38 [The just one]. Moral values were clearly of great importance to Blum, but it was in the name of such values that he made disastrous decisions, such as the refusal to send arms to Republican Spain and the appeal to the French upper classes not to export capital. In effect, he was taking moral decisions for his own side “while expecting the other side to feel morally obliged to follow the example” [en comptant que le camp adverse s’estimera tenu moralement de suivre l’exemple].39

She also looked at the crushing of social democracy in Austria in the early 1930s, showing how the moralising attachment to legality of the Social Democrats prevented them from mobilising direct action by the working class to resist right-wing violence.

Her aim, therefore, was to develop a critique of both Stalinism and social democracy (focussing on the theme of morality) which would enable the socialist movement to go beyond the limitations of both currents, to transcend them both in the direction of a new movement. “This transcendence, for both Communists and Socialists, is our task at the present time” [Ce dépassement, pour les communistes comme pour les socialistes, est la tâche de l’heure].40

This would mean, not simply creating a new organisation, but transforming the human beings who made up that organisation: “transcending what they used to be in the collective enterprise of the party” [dépasser ce qu’ils étaient dans l’entreprise collective qu’est le parti].41

One question which Audry confronts is that of ends and means. Those seeking to radically transform society have to determine which means are effective or ineffective, which are morally permissible or impermissible.

However, Mélenchon is somewhat misleading when he contrasts Audry’s ideas on morality to those put forward by Trotsky in Their Morals and Ours, which he summarises as “the end justifies the means”42 [la fin justifie les moyens].

In fact, Trotsky quite explicitly rejected the position that the end justifies the means. On the contrary, he argued for “the dialectic interdependence between means and end”. The end – a socialist transformation – was not something already defined but would be shaped and determined by the means employed to achieve it. Hence he argued: “When we say that the end justifies the means, then for us the conclusion follows that the great revolutionary end spurns those base means and ways which set one part of the working class against other parts, or attempt to make the masses happy without their participation; or lower the faith of the masses in themselves and their organization, replacing it by worship for the ‘leaders’.”43

Audry recognises that this is Trotsky’s position; in fact, she quotes, with apparent approval, this very passage from Trotsky’s Their Morals and Ours. And, alluding ironically to the vilification of Trotsky within Stalinist parties, she notes that any Communist, presented with Trotsky’s formulation, would have to agree with it, so long as the author’s name was not revealed.44

Audry makes no attempt to equate Trotsky and Stalin; she clearly identifies unequivocally with the Left Opposition to Stalinism. She recognises the validity of Trotsky’s argument that the end is not independent of the means used to achieve it but is shaped by those means. Nonetheless, she has a significant reservation about Trotsky’s formulation concerning ends and means.

If, as Trotsky argues, our criterion in making a choice should be what best leads to the success of the revolution, the problem remains that, in any particular circumstance, “the interests of the revolution are not necessarily obvious” [les intérêts de la révolution ne sont pas forcément évidents].45

Activists may disagree as to what is the best means to achieve a desired end. How is it possible to decide between the different evaluations of those who share a commitment to the same end? As she points out, monolithic Stalinism, which permits no democracy within the organisation, is lacking in safeguards [garde-fous]. If the reputedly omniscient leader makes disastrous errors, there is no means of correcting them until circumstances enforce a change of line.46

(It is worth noting that the argument about ends and means has evolved since the time Audry wrote her book. During the period of Cold War anti-communism, it was common to attack Communists for believing that the end justifies the means, saying that this proved their essential immorality.

But, more recently, the argument that the end justifies the means has been adopted by the defenders of Western imperialism. Asked in 1996 if killing half a million Iraqi children was justified, US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright responded that “the price is worth it.”47)

On the basis of her critique of Trotsky, and of her much more fundamental opposition to Stalinism, Audry develops one of the most important themes in her book, the need for democracy within socialist organisations. In the absence of a self-evident way forward and of an infallible leader, the only way decisions can be made is through debate among the membership and the confrontation of alternatives.

Audry completely rejects the claim that Lenin led directly to Stalin. As she points out, Lenin was frequently challenged within the leadership of the Bolshevik party, and sometimes found himself in a minority.48 It was only in 1921 that the right to form factions was suspended in the Bolshevik party, and this was seen as an exceptional necessity in a situation of grave danger for the revolution.

The right to form an organised faction also existed in the French SFIO. Audry herself had been an active member of the Gauche Révolutionnaire. In fact, as she shows, the whole history of the socialist movement has been a history of debates and disputes within and between organisations. Only through such internal debate is it possible to confront questions of tactics and strategy, of ends and means. As a result, democracy itself becomes a moral value.

In particular, Audry looks at the question of lying within the party. Her critique is not based on the idea of truthfulness in traditional morality. Audry recognises that context defines everything. As a former member of the Resistance, she would have no problem with lying to the Gestapo to protect a comrade.

Lying within a purportedly socialist party was a different matter. Here, all members were supposed to be equal comrades, yet the leadership found it necessary to lie to its own membership. The worst examples came from the Stalinist tradition, and Audry cites several cases. Dominique Desanti, who after being influenced by Sartre joined the PCF, wrote on party instructions a whole book devoted to vilifying Yugoslav leader Tito after he had broken with Stalin49.

But reformist social democrats were also guilty. She cites Rosa Luxemburg as saying that reformist leaders treated the masses like children, who must be protected from the truth in their own interests.50

Audry takes virtually all her examples from France, Austria, Russia and Eastern Europe. She has nothing to say of the tortuous history of the British Labour Party. But her point would be well illustrated by the current leadership of Keir Starmer, who manipulates the membership in the interests of his own version of reality, suspending and excluding members who deviate from his own imposed version of the “truth”.

In describing the democracy required within a socialist party, Audry invokes the principle of reciprocity. This is a key notion for her, and essentially implies the equal participation of all in the process of developing the party’s practice. There can be no reliance on an infallible leader, no manipulation of, nor lying to, a membership judged too immature for the truth.

Applying the principle of reciprocity would mean, according to Audry, a recognition of the equality of all members: “the full and total participation of the others in determining the aims and in the action of the whole party” [la participation pleine et entière des autres à la détermination des objectifs et à l’action de tout le parti].51

Moreover, Audry argues, reciprocity is not just a necessary principle of party organisation, but it lies at the very heart of the socialist society that we aspire to build: “the morality of a socialist society would mean the exercise of generalised reciprocity” [la moralité d’une société socialiste coïnciderait avec l’exercice de la réciprocité généralisée].52

She goes on to suggest that the application of the principle of reciprocity in a socialist society would take the form of autogestion [self-management]. Autogestion was much discussed in the 1970s and 1980s, although (or perhaps because) the term had a fatal ambiguity, meaning something between workers’ control and workers’ representation in management. But she refers to this only briefly and does not develop the argument.53

Recent years have seen the emergence of a new generation of activists, radicalised by Black Lives Matter, by the defence of Gaza and by the demonstrations in opposition to the Rassemblement National. They will have to invent and develop their own organisations and strategy; there is no ready-made programme for them to adopt.

But that does not mean they have nothing to learn from the past. History does not repeat itself, but the experience of history has much to teach us. In particular, we need to understand the failures of both Stalinism and social democracy. So it is important to look to those who attempted to go beyond the existing forces on the Left. Among them, Colette Audry was a significant figure who deserves study.

1 J.-L. Mélenchon, De la Vertu, Paris, Éditions de l’Observatoire, 2017, p. 14.

2 Colette Audry, Les militants et leurs morales, Paris, Flammarion, 1976.

3 For example, in a lecture of 22 April 2024 https://www.youtube.com/live/SV8G6xqB3qM

4 For a biography see https://maitron.fr/spip.php?article10428

5 I. Birchall, “Marceau Pivert Was a Key Figure in the History of French Socialism”, Jacobin, 10 December, 2022 https://jacobin.com/2022/12/marceau-pivert-france-socialism-mass-workers-organization-strategy

6 Le Populaire, 27 May 1936 https://www.marxists.org/francais/pivert/works/1936/05/pivert_19360527.htm

7 Y. Craipeau, Le Mouvement Trotskyste en France, Paris 1971, pp. 123–4.

8 Colette Audry, ʻUne philosophie du fascisme allemand: lʼoeuvre de Martin Heideggerʼ, LʼEcole émancipée, 14 October 1934, pp. 34–5, and 21 October 1934, p. 53. See I. Birchall, “Prequel to the Heidegger Debate”, Radical Philosophy March-April 1998.

9 Maitron and Pennetier’s Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier français, volume 16, pp 481-84, lists about 550 people who belonged to a French Trotskyist organisation before 1939; Audry is not included.

10 See A. Durgan, “Trotsky and the POUM”, International Socialism 2/147.

11 D. Guérin, Front populaire: révolution manquée, Paris: Julliard,1963, pp 255-9.

12 Les Temps modernes, July 1949.

13 Les Temps modernes, May, June, July 1953.

14 Les Temps modernes, November 1953.

15 “Opération Kanapa”, reproduced in Situations VII, Paris, Gallimard, 1965.

16 Combat, 6 October, 1960.

17 L’Express, 11 May 1961.

18 L’Humanité, 4 May, 1968.

19 Le Monde, 8 May, 1968.

20 I. Birchall, “Mitterrand’s War”, Jacobin, 5 June 2016; F. Malye & B. Stora, François Mitterrand et la guerre d’Algérie, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 2010.

21 See the final section (at 1 hour 18 minutes) of https://www.youtube.com/live/yDDlHRuweWc

22 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 142.

23 Paris, Gallimard, 1983; Paris, Gallimard, 1963; Paris, Gallimard, 1984.

24 Paris, Julliard, 1955; Paris, Seghers, 1966.

25 Paris, Julliard, 1955.

26 Paris, Denoël, 1992.

27 D. Guérin, Fascisme et grand capital, Paris, Maspéro, 1969, pp. 73–6.

28 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 12; J-P Sartre, Saint Genet, Paris, Gallimard 1952, p. 177.

29 J.-P. Sartre, L’Être et le Néant, Paris, Gallimard, 1943, p. 515.

30 Sartre, L’Être et le Néant, p. 722.

31 J.-P. Sartre, Cahiers pour une Morale, Paris, Gallimard, 1983.

32 D. Bair, Simone de Beauvoir, London, Cape, 1990, p. 325.

33 J. Gerassi, Jean-Paul Sartre — Hated Conscience of His Century, vol. I, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989, pp. 111, 139.

34 Bair, Simone de Beauvoir, pp. 325, 379-80, 680.

35 See for example Marie-Louise Barron in Les Lettres françaises, 23 June 1949.

36 Combat, 22 December 1949.

37 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 61.

38 Audry, Léon Blum ou la politique du Juste.

39 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 28.

40 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 18.

41 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 148.

42 De la Vertu, p. 14.

43 L Trotsky, Their Morals and Ours, 1938 https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1938/morals/morals.htm

44 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 53.

45 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 47.

46 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 159.

47 https://www.newsweek.com/watch-madeleine-albright-saying-iraqi-kids-deaths-worth-it-resurfaces-1691193

48 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 95.

49 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 83.

50 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 153.

51 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 161.

52 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 148.

53 Les militants et leurs morales, p. 163.