Barbara C. Allen

The Workers’ Opposition was a 1920-22 political faction in the Russian Communist Party that advocated trade-union management of the economy through a system of worker-elected representatives. It consisted of Communist metalworkers who led trade unions and industry. Its major centres of support included industrial areas of Russia and Ukraine (Kharkov, the Donbas, Odessa, Nizhny Novgorod, Samara, Omsk, Ryazan, Krasnodar, Vladimir, and Moscow). Regional nuances ran through the Worker Oppositionists’ proposals, analysis, and behaviour.1

The term ‘workers’ opposition’ in the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party historically originated in Ukraine in 1900, when radical intellectuals [intelligenty] applied it to uncooperative groups of workers in Ekaterinoslav and Kharkov. As a hostile term, the name drove a wedge between worker andintelligent socialists.2 The 1920s group’s most visible political work was in Moscow, the capital of the RSFSR. Its supporters in Ukraine were never as numerous as the supporters of other opposition movements there, such as the Democratic Centralists or Trotskyists. Nevertheless, study of Worker Oppositionists in Ukraine is essential to understanding oppositionism across Soviet space and the relationship between oppositionism and the party and police institutions.

Distinctive characteristics of the Workers’ Opposition in Ukraine included: 1) its members’ specific objections to the merger of the Borotbists (Socialist Revolutionaries) with the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine; 2) its multi-ethnic membership (Russians, Jews, and Ukrainians); and 3) the challenge it faced in the appeal of the Makhno anarchist insurgency to workers. The economic dilemmas its members faced as trade-union leaders and managers of Soviet industry undermined the vision of the Worker Oppositionists in Ukraine. This paper highlights some aspects of Worker Oppositionists’ activities in Ukraine before and after their defeat in 1921.

The idea for this project emerges from my 2015 biography of Workers’ Opposition leader Alexander Shlyapnikov,3 but the paper is based on research I conducted in summer 2017 in the Central State Archive of Public Organisations of Ukraine (TsDAHO) the Central State Archives of Supreme Bodies of Power and Government of Ukraine (TsDAVO), and the State Archive of the Security Services of Ukraine. I examined and took notes from about 200 files in the first two archives and took 1930 digital photos of pages from security service archive files on the case of the Workers’ Opposition in the 1930s and from personal case files of seven former Worker Oppositionists who were arrested in Ukraine in the 1930s and politically repressed (Petr Bykhatsky, Ivan Dudko-Petinsky, Moisei Goldenberg, Semen Kozorezov, Mikhail Lobanov, Grigory Sapozhnikov, and Isai Shpoliansky).

Worker Oppositionists in Ukraine confronted additional challenges to those facing the group’s supporters in central Russia. At a CP(b)U congress in March 1919 in Ukraine, Lavrentev, who would later join the Workers’ Opposition, caused a stir when he spoke of “completely new tasks for trade unions.” Yet he also acknowledged the challenge posed by Bolsheviks’ lack of a majority in Ukraine’s trade unions, which were controlled, he said, by Mensheviks who had been ousted from trade unions in Russia. When they would achieve this, he said, trade unions “organise the entire economy,” “compose the Council of Economy and the highest body of the economic policy in full,” “organise the Commissariat of Labour,” and assume “all the work of organizing production and labour.” He called for Bolshevik party committees to take control of trade union leading bodies at the upcoming All-Ukraine Congress of Trade Unions.4 He did not acknowledge the irony that this would set a precedent for Communist Party interference in trade union leadership matters.5

The All-Russian Central Council of Trade Unions (VTsSPS) created a Southern Bureau (Iuzhburo) in 1920 to organise trade unions in Ukraine, but ongoing military conflict undermined its work and the composition of its leadership changed frequently. A Iuzhburo report also pointed to “banditry” as a “specifically Ukrainian phenomenon” and as harmful to the organisation of unions. Besides those, political authorities frequently changed, Finally, Menshevik influence was stronger far longer in parts of Ukraine than in the Russian centres. These conditions led to “lack of discipline” and “samostiinost” (Ukrainian separatism), according to Iuzhburo. Efforts were focused on the gubernias where heavy industry prevailed: Donetsk, Ekaterinoslav, Kharkov, Odessa, Kiev.6

Organizing a Bolshevik Southern Bureau (Iuzhburo) of the All-Russian Metalworkers’ Union in Ukraine was only possible after the Whites’ counterrevolutionary armed forces had been cleared from the territory in December 1919. As the Whites retreated, factory owners and directors left, too, which left management in the hands of worker organisations controlled by Mensheviks, which Bolsheviks “dispersed”. This seems to have been an overwhelming challenge to Iuzhburo VSRM. Lavrentev and other personnel returned from Moscow in February 1920 and undertook early organizational work. Lavrentev focused on wage rates. Leadership changed after the 3rd All-Russian Metalworkers’ Union Congress. The new Iuzhburo leader, Mikhail Lobanov, who had arrived by June 1920, shifted his attention to organizing production and working through government economic bodies.7

Born in Moscow gubernia to parents who worked in weaving and woodcarving, Lobanov was educated at home and in revolutionary study circles. He joined the Bolshevik party in 1903 and the Metalworkers’ Union in 1905. Due to his exceptional talents, he was chosen to attend Maxim Gorky’s school at Capri in 1909-10. He also went to Paris and attended Lenin’s lectures (he is referenced as “Stanislav” in Lenin’s Sochineniia). In 1917, he helped organise the party and trade unions in Moscow. In 1918-20 he worked in the Commissariat of Labour, the Metalworkers’ Union CC, and the Soviet. In Ukraine, he worked in union, party, and economic bodies in Ukraine until 1929, when he was transferred to the Urals for economic work.8

Other prominent Worker Oppositionists also operated in Ukraine in summer 1920. Flor Mitin was directed to chair the Lugansk gubernia trade union council on June 30, 1920.9 Iurii Lutovinov participated in a meeting of senior communists of Lugansk party organisation on 9 August 1920, where there was a report about the problem of communists leaving the party, ostensibly for family reasons, illness, or lack of time. Arguing against opinions that those who left were self-seekers or politically illiterate, Lutovinov argued that central party and state policy was at fault for being insufficiently communist, and that too many alien elements in the party pushed out workers and poor peasants. He called “to workerise the communist party” by bringing in a mass of new members from the working class “in such a way … that it would take the leading role in Management of the Soviet Republic.”10

By mid-September 1920, party leaders of Ukraine expressed concern to one another about Lutovinov having created organised support for the Workers’ Opposition in Donbas, which, in their eyes, had become mixed up with Nestor Makhno’s anarchism. They expressed the need for strong leadership and better organization at the uezd andvolost levels.11 Around the same time, Mitin, Lobanov, and some other Workers’ Opposition supporters spoke at an all-Ukrainian meeting of trade unions, where Mitin proposed a resolution, which was accepted, criticising the Council of Defense’s appointment of metals section chiefs and board chiefs without having consulted trade unions.12

The Worker Oppositionists met rude pushback from Ukraine party leaders. In October 1920, Andrei Ivanov, a former metalworker who had become a CP(b)U CC member and chair of the VTsSPS Southern Bureau, tried to assign Iuzhburo VSRM member Pavlov to work in committees of poor peasants, without the permission of Iuzhburo VSRM. He threatened to set the Cheka on Lobanov and others for not complying. Lobanov offered himself to Ivanov in Pavlov’s place. Ivanov took the bait, but this elicited the interference of the CC VSRM, because Ivanov’s order violated CC RCP(b) decision on how to mobilise Metalworkers’ Union personnel.13

On behalf of the Workers’ Opposition, Perepechko, Antonov, and Kuznetsov spoke at the 5th CP(b)U conference in Kharkov, November 1920, supported by at least twenty delegates. They were especially aggrieved over the influence of former Borotbists (Left SRs) within the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine, which added a specific cast to the broader allegations of ‘petty-bourgeois’ elements flooding into the party that Workers’ Opposition leaders in Moscow and other areas lodged. Zinoviev spoke against them. Excerpts of their speeches were included in a document collection he edited, but I found the full versions in the Ukrainian archives.Perepechko felt that the CP(b)U was too invested in the work of committees of poor peasants and insufficiently seeking support among the proletariat.14 Antonov agreed with Perepechko on many points and faulted the CC CP(b)U report for not mentioning trade unions and connected it to neglect of the working class’s leading role. Controversially, he claimed that communist inattention to the working class allowed Makhno to gain support among factory and mill workers, who he said stood “in line for his assemblies by the tens of thousands.”15 Antonov read a resolution in the name of the Workers’ Opposition, but I could not find its text in the files.16

Perepechko denied Zinoviev’s assertion that mobilisation of communists for the front contributed to a crisis in the party, for Moscow trade unions, he said, followed a proletarian class line. A “petty bourgeois element” “deeply hostile to the proletariat” was “inundating the party.” He denied that the Workers’ Opposition was hostile to the intelligentsia. The only way to ensure proletarian influence over the party and soviets was “to restore their rights to the trade unions.” He read aloud theses of the Workers’ Opposition.17

Kuznetsov spoke of the fear of reprisals for speaking freely in support of the Workers’ Opposition. The common expression for this was being “sent to eat peaches,” but he said that some were sent where there were no peaches at all. He referred to communists being shot in Volhynia. He complained that one could not voice criticism without being called a Makhnoist or Menshevik.18 Kuznetsov wound up by acknowledging that much of what the Workers’ Opposition wanted was in the conference’s common resolution, which it could support, but that it would “reserve the right to voice disagreement in the future.”19

On the eve of the 10th All-Russian Party Congress, Workers’ Opposition representatives (Pavlov, Mitin, Polosatov, Kuznetsov) spoke out at the 4th Donetsk gubernia CP(b)U conference in mid-February 1921.Polosatov struck many familiar notes of the Workers’ Opposition’s platform, such as that the party had become isolated from the working class. He called for struggle against engineers’ and technicians’ influence over the party. Not only the “vanguard of the working class” but the entire class down to the local level should build the economy. Involvement by trade unions and soviets would not weaken the party’s role, but strengthen it, for the party “will guide the trade union movement.” He spoke of linkinggubernia level party committees, trade union councils, and soviet executive committees, but without specifics. Isolation among these bodies he blamed on Trotsky and his supporters. He denied there was anything wrong with groupings in the party, which were always part of party life “both in the West and in Russia”, if they observed party discipline. Destroying groupings was “not a Marxist approach.”

At the same conference, Kuznetsov argued that the worker was basically a communist and could be drawn into the party and its work if the party would do more to attract workers. Workers, he said, ought to be united more broadly in trade unions, which should expand their work and channel workers into the party. Soviets used to be like a powerful parliament, but had become just an executive “troika”. Strengthening both trade unions and soviets would lead to a stronger party more anchored in the working class. The Workers’ Opposition just wanted to eliminate the party’s “illnesses”, not to oppose for the sake of opposition.20

At the Tenth Party Congress in Moscow, the Workers’ Opposition was censured and banned. Through 1921, party leaders engaged in a campaign of suppression to neutralise its influence within party and trade union organisations. Some of this is described in my biography of Alexander Shlyapnikov.

In Ukraine, the metalworkers’ inability to resist party leaders’ campaign of repression was hindered by poor communications between Iuzhburo and CC VSRM in Moscow.21 Party leaders’ efforts to quash oppositionism was phrased in terms of “strengthening” the unions, such as the Metalworkers, which harboured oppositionists.22 Politburo CC CP(b)U records contain frequent references to personnel transfers of Workers’ Opposition supporters. Fall 1921 transfers of people from Nikolaev was related to the strength of the Workers’ Opposition there. At the same time, distribution of bread to hungry workers in Nikolaev was meant to dilute their grievances.23

The influence of the Workers’ Opposition within central bodies of the Metalworkers’ Union was reduced. At the same time, new issues related to the introduction of the New Economic Policy changed the terms of oppositionism. In August or September [?] 1921, Iuzhburo VSRM expressed concern to CC VSRM, VTsSPS leading bodies, and CC CP(b)U about Gosplan desires to lease large metals industrial enterprises and coal mining operations in Donbas to Belgian capitalists. Iuzhburo pointed out that it demoralised economy personnel to read in press articles that old private capitalist ‘bosses’ could return. Iuzhburo called for a special session of CC VSRM to discuss the matter. It claimed not to oppose “concessions in general or leasing” but did not want the entire economy turned over to capitalist entrepreneurs.24

By the 21 September 1921 session of Iuzhburo, Lobanov had been demoted to assistant chair, with [ ] Ivanov replacing him as chair. Nevertheless, former Worker Oppositionists still had a strong presence in the bureau (Skliznev, Tolokontsev, Mitin [and Poliakov, Prasolov?]).25 In late September 1921, they were debating the merits of collegial vs. one-man management for industrial combinations.26 In early October, Mitin informed the Iuzhburo VSRM that the CP(b)U Don gubernia committee had recalled him from the Don raikom of VSRM. They objected that this was not supposed to be done without the permission of the Union CC’s communist fraction bureau. They told Mitin to remain in his post until the CP(b)U Politburo would resolve the question upon an appeal through the Iuzhburo of VTsSPS.27

Yet it was difficult for Iuzhburo VSRM to protect former Worker Oppositionists when it faced even greater problems of scarce resources for union work, insufficient food and clothing for workers, and violations of wage rates agreements. Trade unions had to find food and fuel for workers, so that they could work and would not go on strike. In addition, trade unions often had to oversee enterprise leases, if sovnarkhozes neglected their duty. At one factory, the management was all arrested without consulting the trade union. Theft was also a problem in factories. The bad harvest stifled official bodies’ ability to show initiative.28 Finally, Iuzhburo VSRM had conflicts with sovnarkhozists about management of Iugostal and other trusts.29

By December 8, 1921, Lobanov returned to his position as chair of Iuzhburo VSRM.30 But pressure contined upon Mitin, especially at the hands of CC member and formal metalworker Andrei Ivanov, who chaired Iuzhburo of VTsSPS. Mitin complained in a letter, with support from Lobanov, Perepechko, and others, that Ivanov denied Mitin’s nomination to CC CP(b)U. The denial was phrased in extremely offensive language, accusing Mitin of having been a Menshevik who joined the Bolsheviks out of self-seeking motives and of having demoralised the party and the Donbas.31 CP(b)U members in Iuzhburo CC VSRM wrote to Politburo to explain the detrimental impact that reprisals against Worker Oppositionists had on Metalworkers’ Union and trade union work generally. First, there were not enough communists in the trade union movement because trade unions had until only recently been in Menshevik hands and there were still many Mensheviks in the movement. Party bodies’ distrust toward Workers’ Opposition supporters in trade union leading bodies also hurt work among unions and in the economy. Metalworkers in large industrial centres were not allowed seats in gubernia trade union councils, which undermined work. They asked for party leaders in Ukraine to emphasise that metalworker representatives should be allowed ingubernia trade union council presidiums, to send them more senior metalworker communists, allow those purged from party to continue in union and economic posts until a replacement would be found, and insisted that members could not be removed from Metalworkers’ Unionraikoms bygubernia trade union councils and party committees without the permission of Iuzhburo VSRM. People should not be transferred just because they belonged to a pre-congress factional grouping.32

In January 1922, CP(b)U leadership blamed the Workers’ Opposition for the murder of an engineer in Donbas. A worker party cell meeting called for release of the party secretary who killed the engineer, because “proletarian instinct guided” him to carry out the act.33

On 10 January 1922 when Iuzhburo VSRM met, Lobanov was still chair and Skliznev was secretary. Others present included an Ivanov who was chair of the Metals Board of Ukraine and Kolesnikov from Iuzhburo VTsSPS. They objected to the VTsSPS order on wage rates as “completely unacceptable in Ukrainian conditions” and resolved “to energetically protest against its implementation at the current time in Ukraine.”34 This shows they still had fighting spirit. Nevertheless, they could not prevent reprisals against their comrades.

In early 1922, two former Worker Oppositionists named Gorlovsky and Shpaliansky addressed higher party bodies (incl. the CC RCP(b), CC CP(b)U) explaining their decision to leave the party. Their first grievance was the pressure that the party leaders had placed on the 1921 congress of trade unions’ communist faction, resulting in the CC’s rejection of wage rates proposals passed by the congress communist faction, which “demoralised communist trade unionists.” But, they wrote, provincial party leaders exceeded central ones by exerting “the rudest, clumsiest, most tactless, and most unjustified pressure” on the communist faction at the third gubernia congress of trade unions in Nikolaev. The congress was so undermined that its communist faction did not want to vote and was only forced to do so by party discipline. Many of the congress’s faction members wanted to turn in their party cards right then. At first, reprisals came individually against Worker Oppositionists by removing them from posts or transferring them, then entire organisations were dispersed for spurious reasons. Manuilsky mobilised nearly all former Worker Oppositionists from the Nikolaev party organisation, including authors of this letter, to go to guard the Soviet border with Poland and Romania. But, in fact, most were sent not to guard the borders but to “diverse places”. That is how the authors landed in Omsk, Siberia, where they met suspicion that they might continue oppositionist factionalism. They believed the distrust shown toward them led to contradictions and sudden changes in their work assignments, which made it impossible for them to work within the party and motivated their decision to leave.35

At the same time, when Iuzhburo VSRM heard of and lodged protests about Donetsk party leaders forced re-election of delegates to Fifth Congress of Metalworkers’ Union, they also had to discuss factory debt, unemployment, clothing for employed workers, management’s failure to fulfil commitments to workers, etc.36 Iuzhburo VSRM leaders went themselves to conduct district conferences in Kharkov, Bakhmut, and other cities, but this was not enough to prevent irregularities.37

By summer 1922, Iuzhburo VSRM was overwhelmed by the crisis of indebtedness in the metalworking industry, which gave rise to strikes and disturbances.38 They attempted to arrange payment in kind by food supplies to workers of the Ukraine agricultural machinery trust.39 They were also attempting to cope with the reorganisation of metalworking industry in the conditions of the New Economic Policy and of a capital shortage.40

By August-September 1922, members of Iuzhburo VSRM were being reassigned to work in metals and machinery trusts, at least partially according to their own wishes, because they found it impossible to carry out work in Iuzhburo. Lobanov was assigned by Sovnarkom to the Ukrainian Economic Council presidium, but remained chair of Iuzhburo until his replacement arrived. Iuzhburo VSRM nominated Mitin as a board member of the Ukrainian Metallurgical Trust.41 Kubyshkin and Skliznev became board members of the Ukrainian Trust of Agricultural Machinery. As Iuzhburo’s leadership broke down due to transfers and lack of replacements, the presidium relinquished initiative to district committees of Metalworkers’ Union to carry out their own wage rates negotiations with boards of trusts and with factory managements.42

By the end of September 1922, Iuzhburo VSRM had a new chair in Pavel Arsentev.43 But lack of money to pay workers’ wages continued to cause problems, especially in Nikolaev.44 This, along with the poor harvest, resulted in deaths of workers. In late October it was revealed in a Iuzhburo report that in Nikolaev factories, “400 skilled workers died of starvation from January to August.”45 Despite movement of Iuzhburo leaders into trusts, trade unions still could not work effectively with economic planning personnel, as reported by Skliznev at a meeting of VSRM Ukraine organisations in December 1922, and this exacerbated the problems with protection of the workforce.46

Although dispersed from trade unions into economic bodies, former Worker Oppositionists continued to associate informally and to speak out during periods of open party debate in the 1920s. The evidence I have found indicates that they maintained a distinct identity based on their former coalescence as the Workers’ Opposition and did not merge with Trotskyist or Zinovievist oppositionist groups. Lobanov has been misidentified as a signatory of the Declaration of 46 in 1923, an act which led to the formation of the Trotskyist Left Opposition, but the signature on the statement does not look like his signature I have seen elsewhere. It must have been a different Lobanov.

At the October 1926 all-Ukrainian conference of the CP(b)U, Kaganovich and other speakers slammed Shlyapnikov, Medvedev, and connected the old Workers’ Opposition, which Lenin had condemned, to the United Opposition of Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Kamenev. Lobanov was among those demonised in Kaganovich’s speech.47 As a guest rather than full voting delegate, Lobanov managed with difficulty to obtain permission to speak and his appearance was “met with noise and laughter.”Defenders of the Soviet Party leadership’s line interrupted him nearly forty times, with mockery and ridicule. Sarcastically knocking his audience’s knowledge of party history, he complained that one could not criticise but could only “sing hosannas to our most supreme CC.” He defended his own history in the party as one of the “ants who assembled the party” in the underground before 1917. An audience member questioned why he still held an important work position, but Skrypnik interjected that Lobanov should not worry about being removed from his job. Lobanov asserted that the former Workers’ Oppositionists should be allowed to write their own history rather than be judged according to distorted textbooks on party history. His own account of the Workers’ Opposition’s origins lay in its discontent over the “nonproletarian element” in the party, the payment in gold roubles for foreign locomotive orders at a time when Soviet factories had too little work and workers were starving. He claimed that party leaders had accepted some Workers’ Opposition proposals, such as the purge, and that it had cancelled some foreign orders. He saw the Workers’ Opposition as having succeeded in convincing the 10th party congress to pass a resolution “about democracy and about bringing the working class closer to the leadership.” He pointed out that Shlyapnikov had successfully parried Lenin’s charge of syndicalism at the 1921 Miners’ Congress by pointing out that the Workers’ Opposition could not be syndicalist, because production in the RSFSR was already in workers’ hands, whereas syndicalists pressed for workers to own production in capitalist society. He claimed that Lenin no longer used the term after the Miners’ Congress. Furthermore, he said, Lenin did not treat Shlyapnikov as an enemy. He portrayed Lenin and Shlyapnikov as equals in the party. Analysing the economy of 1926, he expressed scepticism about reported economic successes, for industrial capital was nearly exhausted, especially in Iugostal. Productivity could not be increased further without new machinery and new capital. He was concerned about the growth in unemployment: “who does not have an unemployed person in your family?” Yet beyond advocatingsovkhozes and sarcastically a medal for those who do not interfere in the work of the economy, he did not seem to offer brilliant solutions to acquire new capital.48 Lobanov was followed by a round of attacks upon him, his positions, and his version of party history.49

At the same conference, a reference was made to Sapozhnikov continuing to maintain oppositionist views (as having stated at a party committee plenum in Kiev that trade unions were deceiving the working class).50

Although the Worker Oppositionists seem to have ceased to make public critical comments by 1928, many of them were swept up into the Stalinist terror of 1935-8, arrested, interrogated, charged falsely, and tried in secret. It appears that the NKVD was attempting to assemble the elements for a show trial of the Workers’ Opposition, whether separately or together with other former oppositionist groups.

Lobanov left Ukraine for work in the Urals during the First Five Year Plan, but returned in the early 1930s to Kharkov, where he was arrested on the fabricated case of the Workers’ Opposition in 1936. Lobanov was arrested in Kharkov in August 1936 and sent by special convoy to Kiev. Accused on case of Workers’ Opposition in November 1936. The NKVD accusation against him of terror claimed he confessed to charge. He was condemned in Moscow in March 1937 by Military Collegium of Supreme Court. But when he appeared before the court, he retracted the part of his confession to terrorist activity. Said he did not belong to the Trotskyists, but that he was one of leaders of Workers’ Opposition in Ukraine and it created a bloc with Zinovievists but not with Trotskyists.51

The Ukrainian Bykhatsky was a young supporter of the Workers’ Opposition in 1921 who seemed to have regretted his ‘instinctive’ (his word) vote for Lenin’s platform on trade unions and determined to show more ‘political maturity’ as he continued to defend the views of the Workers’ Opposition later in the 1920s, even as he found social mobility in the Soviet system through education, becoming an engineer from his starting place as a metalworker. He visited Shlyapnikov and Medvedev in Moscow in the early 1930s, visits which the NKVD attempted to construct as conspiratorial encounters. Bykhatsky was arrested in 1934 and exiled to the Kazakh SSR, where he seems to have died in a prison camp sometime during World War II.52

Sapozhnikov was repeatedly interrogated and broke down from initial defiance to apparent readiness to testify with the most damning charges against Shlyapnikov, Medvedev, and other alleged members of a Workers’ Opposition ‘centre’ in Moscow. The NKVD took Sapozhnikov from Kiev to Moscow for closed trial, where he recanted the most damning charge he had made against fellow Worker Oppositionist Sergei Medvedev – about having approved individual terrorist acts. Although he was brought to Moscow to stand trial at a closed session of the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court, he recanted the part of his testimony with the most damning charge against Medvedev, that of having urged individual acts of terror against Soviet leaders. This may have contributed, along with Shlyapnikov’s and Medvedev’s failure to confess and the death from heart failure of Mikhail Chelyshev during the investigation, to the unravelling of the NKVD’s case against the alleged Workers’ Opposition. 53

In the NKVD investigations of these individuals and others associated with them in the 1930s, Jewish Worker Oppositionists seem to have become more prominent as targets of repression. The NKVD preserved only one case file of interrogation protocols relating to the Workers’ Opposition in 1936, as compared to dozens of files on Trotskyists. Correspondingly, only a few dozen people in Ukraine seem to have been targeted as Worker Oppositionists, as compared to many thousands of Trotskyists. Trotsky supporter N.V. Golubenko was a major figure targeted in the NKVD case against the Trotskyists in 1935-8 in Ukraine. He was acquainted with some of the Worker Oppositionists targeted and his testimony against them played a key role in their arrests and convictions. The interrogators treated the former Worker Oppositionists as a subset of the threat they perceived from Trotsky supporters in the 1930s. Some of those they targeted became Trotskyists or had always been Trotskyists, while others had attempted to maintain a separate identity as former Worker Oppositionists while voicing support for Trotskyist proposals.

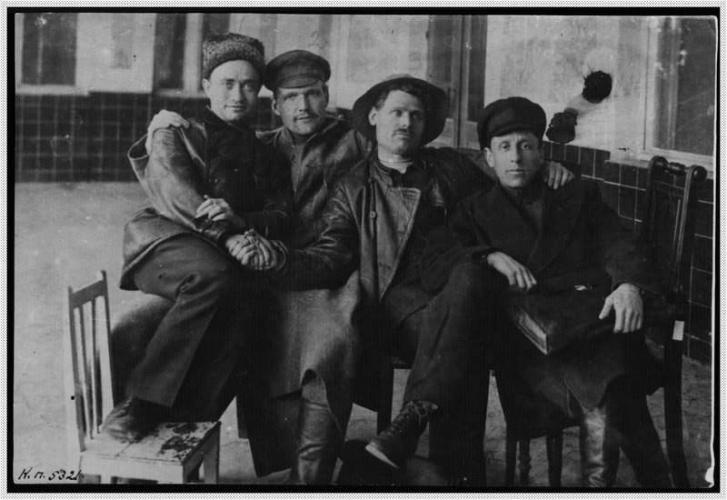

Caption: Members of the Workers’ Opposition at the Fourth Party Conference of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine. 1920

Source: State Central Museum of the Contemporary History of Russia

- 1. A shorter version of this paper was presented at the Study Group of the Russian Revolution Conference, Cardiff University, Wales, UK, 4-6 January 2018; and the Southern Conference on Slavic Studies, Charlotte, NC, March 22-24, 2018.

- 2. Allan Wildman 1967, The Making of a Workers’ Revolution: Russian Social Democracy, 1891-1903 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), pp. 107–8.

- 3. Barbara C. Allen, Alexander Shlyapnikov, 1885-1937: Life of an Old Bolshevik (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2015; Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2016).

- 4. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 15. ll. 91-93, March 5, 1919 session. During the discussion of the trade union question, the chair admonished delegates for “reading newspapers, carrying on conversations, and making noise” during the discussion, which to him indicated insufficient interest in the trade union movement’s work (l. 101). This comment, as well as a few lines from Lavrentev’s speech, were struck out in the stenographic record as if they were not to be published.

- 5. TsDAHO, f. 1, op. 1, d. 15, l. 105. The Third Congress of CP(b)U met from March 1-6, 1919, with a preliminary session on February 28. Most of the 170 delegates were from the Donbas, Poltava and Kiev gubernias.

- 6. TsDAVO, F. 2605, op. 1, d. 9, ll. 51-2.

- 7. TsDAVO, F. 2605, op. 1, d. 25, ll. 1, 45, 70-78; F. 2595, opis 1, d. 1, l. 4, l. 10.

- 8. TsDAHO, f. 23, op. 1, d. 56, ll. 1-22. Lobanov, Mikhail Ivanovich. 1932-34, Kharkov, application for membership in the Society of Former Political Prisoners and Exiles. He was on leave from an assistant manager in an economic trust. His application was approved.

- 9. TsDAVO, F. 2595, opis 1, d. 1, l. 14.

- 10. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 20, d. 213. l. 110 Protocol no. 1 of soveshchanie of senior personnel communists of Lugansk organization, 9 August 1920. 55 people attended. Chair was Razumov and secretary was Pogrebnoi. The meeting resolved to blame the “mass departure” on “lack of consciousness and political illiteracy.” They also called for a purge of petty bourgeois elements from the party and to “workerise the party and soviet bodies.”

- 11. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 20, d. 143, l. 96. Perepiska, zapisi razgovorov po priamomu provodu s Donetskim gubkomom KP(b)U…. 17 January – 30 December 1920. 19 September 1920 phone conversation between Akhmatov in Kharkov and Drobnis in Lugansk.

- 12. TsDAVO, F. 2595, opis 1, d. 1, l. 27, September 19, 1920.

- 13. TsDAVO, F. 2595, opis 1, d. 1, l. 29 October 5, 1920.

- 14. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 42, ll. 61-2.

- 15. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 42, ll. 65-9, I have found little biographical information about Antonov. He said about himself that he had belonged to the Bolshevik Party for 15 years and had been educated in a cartridge factory (l. 123). He was very active at this conference and spoke several times on behalf of the Workers’ Opposition.

- 16. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 42, l. 123.

- 17. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 42, ll. 165-168.

- 18. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 42, ll. 196, 198.

- 19. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 42, l. 241.

- 20. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 20, d. 453, ll. 7-11. Trotsky group’s theses got two votes, Workers’ Opposition got 21 votes and the Ten got 79 votes. Mitin also spoke. I did not find speeches of Pavlov and Mitin.

- 21. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op.1, d. 20, l. 2 March 14, 1921

- 22. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 6, d. 19. Materialy k protokolam no. 29-41…. 22 March – 19 April 1921.

- 23. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 6, dd. 13, 16, Politburo CC CP(b)U protocols, 2 January – 27 December 1921.

- 24. TsDAVO, F. 2595, opis 1, d. 1, l. 58.

- 25. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op.1, d. 22, l. 7.

- 26. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op.1, d. 22, l. 9.

- 27. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op.1, d. 22, l. 12, October 7, 1921.

- 28. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 5, d. 113, l. 1. Amosov’s speech at [Gorodskoi raion of Dnepropetrovsk?] conference of the Metalworkers’ Union in Ukraine on October 13, 1921,

- 29. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op.1, d. 22, l. 28.

- 30. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op.1, d. 115, l. 26.

- 31. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 6, d. 20. Materials for protocols no. 42-48 of Politburo sessions. 21 April – 14 June 1921. l. 68 handwritten letter from Flor Anisimovich Mitin, dated March 29, 1921. To TsK KPU in Kharkov.

- 32. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 6, d. 28. Materialy k protokolam no. 104-110. Politburo sessions CC CP(b)U. 11 November – 27 December 1921. Signed by Members of Bureau of Fraction of CP(b)U of Iuzhburo CC VSRM Ivanov, Skliznev, and [Lobanov?].

- 33. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 6, d. 29, l. 1.

- 34. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 101, l. 35.

- 35. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 6, d. 34, l. 54. Materials to protokols no. 33-44 of Politburo sessions CC CP(b)U. 31 March – 9 May 1922. Signed by V. Gorlovsky (party ID 882020) and I. Ia. Shpaliansky (party ID 882018).

- 36. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 101. l. 4; d. 102, ll. 83, 89.

- 37. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 102, l. 69, 88.

- 38. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 102, l. 49.

- 39. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 102, l. 31.

- 40. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 100 l. 24

- 41. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 102, ll. 21-22.

- 42. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 102, ll. 7, 10-11, 17.

- 43. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 102, l. 2.

- 44. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 101, ll. 28-29.

- 45. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 101, l. 21.

- 46. TsDAVO, F. 2595, op. 1, d. 103 ll. 43-44. Protocols of joint sessions of Iuzhburo… w reps of other organizations. 1922.

- 47. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 182. l. 22 Stenogramma I Vseukrainskoi Konferentsii KP(b)U. Part 1, uncorrected. 17-21 October 1926.

- 48. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 182. ll. 193-206, uncorrected version; f. 1, op. 1, d. 184, ll. 111-125, corrected version. When I read the uncorrected stenographic record, I thought he sounded rattled and unclear. His corrected version made him sound more persuasive. I cannot be sure which version portrays his demeanor most accurately.

- 49. TsDAHO, f. 1, op. 1, d. 182, ll. 207, 226-227, 239-258.

- 50. TsDAHO F. 1, op. 1, d. 183 l. 183. Stenogramma I Vseukrainskoi konferentsii KP(b)U, part 2, uncorrected copy.17-21 October 1926.

- 51. Lobanov’s 1936-7 case file from Kharkov branch of Security Services Archive.

- 52. Bykhatsky’s case file in TsDAHO.

- 53. Sapozhnikov’s case file in the Kiev branch of the Security Services Archive.