The Problems of Tradition

By Alex Maguire

To paraphrase Marx who, like Lucifer, has all the best lines: a spectre is haunting political discourse – the spectre of the Traditional Working-Class. By Traditional Working-Class (TWC) I do not mean the class itself, instead I mean the typical concept and collection of common misunderstandings that underpins the popular understanding of this class. In the years since the 2016 Brexit Referendum, the term ‘Traditional Working-Class’ has become endemic in political and cultural discourse in Britain.1 Prior to this the term was seldom used, though it did exist as a category in the BBC 2013’s class survey. The term is now probably the most used class descriptor in common discourse (its only rival would be ‘white working-class’ which is used either as a pejorative or a badge of honour); however, it has not been defined who and what this class are. What is this class’ relationship to production, consumption, and other classes? Does the TWC exist, and if so where? What precisely makes them traditional, and what are these traditions? It is necessary to investigate these questions to properly understand what precisely this class is. It should be emphasised that interrogating the concept of the ‘traditional working-class’ is not the same as interrogating working-class traditions. The English working-class has a rich and varied history of traditions. This is indisputable. What is open to question is the precise nature of the TWC.

There have been substantial changes in the material reality of working-class life, and, just as the concept of tradition must be investigated, material changes must also be recognised. There have been substantial demographic changes in many of England’s communities in the last fifty years, capitalism has provided new industries such as platform and call centre work, and working conditions have rapidly declined in the last ten years. The working-class looks quite different today than it did thirty years ago.

In the face of these changes, a common construction of the TWC is that it resides in ex-industrial and mining towns in the North,Midlands, and South Wales, is largely comprised of white male labourers, skilled or unskilled, and is often ignored by metropolitan society. The precise geographic location of this construction is largely a product of Labour’s 2019 electoral defeat in many of these constituencies, and partly accounts for the distinctly English character of this class, even if occasional acknowledgements are made of the impacts of deindustrialisation on towns and villages in Wales.2 This is a glib description that has taken root on both the right and the left. This construction marginalises women, ethnic minorities, and the working-class located in urban centres, particularly those associated with the new industries of the inter-war period, such as electronics and electrical engineering, vehicle construction, chain retailing and bulk clothing production, artificial fibres, aviation, cinema in places such as Coventry and Oxford. While not all uses of this term are as simplistic, most are.3

The description used for the Great British Class Survey is equally problematic. Mike Savage et al. argue that one of the defining characteristics of this class is that ‘old-fashioned’ occupations such as lorry driver, cleaner, electrician, and factory worker, are over-represented in its number. Effectively, they are arguing that these jobs are traditional working-class jobs. ’.4 However, Savage et al. argue, class is not just the job one does, but the specific labour relations that are part of that job. These labour relations are the social relations of production. The authors go on to state that:

‘we might see this class as a residue of earlier historical periods, and embodying characteristics of the TWC. We might see it as a “throwback” to an earlier phase in Britain’s social history, as part of an older generational formation’.

When history is invoked, it must be asked who is invoking it, why are they invoking it, and which specific construction of history are they invoking. Furthermore, the specific notion of tradition is a historically difficult term. Hobsbawm noted that traditions ‘which appear to claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and sometimes invented’.5 While all traditions are at some point invented, and most enjoy liberal relations with historical veracity, unlike Hobsbawm’s traditions, the TWC has not been ascribed a delineated set of actual tradition (such as a common dress sense akin to the early twentieth century ubiquity of the flat cap). Instead, ‘traditional’ is a collection of common ideas that individuals ascribe to and identify, even if these ideas are not materially grounded. Indeed, Hobsbawm observes that the recently invented notions of tradition tend to “be quite unspecific and vague as to the nature of values, rights and obligations of the group membership they inculcate’.6 Perhaps it is this vagueness that has made the TWC such a potent rhetorical device.

To better underline what I think the problems with the concept of the TWC are, I shall provide a brief definition of what I think the English working-class is. The working-class has always constituted an array of relationships and employment conditions. After all, no class is homogeneous and the working-class is made up of different overlapping fractions with their own nuanced relations to production. It is the relative precariousness of these fractions that ensures they regularly overlap. As Satnam Virdee wrote, the ‘labour process imparts on [the working-class] a fractional character, which, in turn, means that at any one moment in time, the class consciousness of the aggregate working class is unlikely to be identical’.7 The English working-class is large and, in some instances, has a significant liminality with parts of the middle-class in terms of relation to production and income. An example of this is how most of the NHS’ junior management is drawn from the shop-floor, meaning that staff are promoted from engaging in production to managing production. Equally, a few high earning members of the labour aristocracy, such as very successful self-employed plumbers and carpenters, will be able afford a middle-class quality of life and often live-in middle-class neighbourhoods. In this sense, the TWC differs from a class such as the British landowning aristocracy which is small enough to regulate entry and can selectively reproduce itself.

The overlapping fractions that constitute the bulk of the English working-class (excluding children and retired pensioners) are: the proletariat, labour aristocracy, organised labour, unorganised labour, wage labourers (who’s employment may be relatively stable but is still tied to a wage), and unpaid domestic labourers. Indeed, throughout their lives, most members of the working-class will have been part of many, and some even part of all, of these fractions. This list is by no means complete, and while it is possible to identify other groups, I think that these categories account for the majority of the working-class and sufficiently illustrate the nuances of this class’ internal relationships. I define the proletariat as being the part of the working-class whose employment conditions are characterised by insecurity, and therefore their employment conditions (though not their culture, sense of class, and assets) may have more in common with some precarious members of the middle-class, for instance actors, than other members of the working-class.8

The term labour aristocracy requires clarification. I do not mean it in the Leninist sense, which refers to the working-class of the western world who benefited from the spoils of nineteenth and twentieth century imperialism. I use the term to describe a group similar to Hobsbawm’s Labour Aristocracy who are ‘better paid, better treated and generally regarded as more “respectable”’, though I reject Hobsbawm claim that this group is innately more politically moderate than the ‘mass of the proletariat’.9 The labour aristocracy are the ‘upper strata of the working class’ who have more control over their processes of production, on account of their skilled labour, which better enables them to navigate the working day.10 Richard Price provided a good description of the Labour Aristocracy when he wrote:

‘the labour aristocracy may be seen not as a fixed group, dependent upon a certain kind of industrial technology or organization, but as encompassing those who were able to erect certain protections against the logic of market forces on the basis of the spaces provided by aspects of segmentation. Thus, to admit the many lines of segmentation within the working class is not to dispose of the problem of the labour aristocracy; it is, rather, to drive it back to its original location in the sphere of production. A fundamental line of cleavage within the working class is between those who are able to realize some protections against market vulnerability and those who are not. In the mid-nineteenth century, this cleavage attained a particular importance and prominence because, in the absence, for example, of political democracy, it provided one of the few ways by which sections of the working class could assert their influence and self-conscious identity in society.’11

As a result of this privileged relation to productive forces, usually on account of possessing specific skills, the labour aristocracy has often organised itself into craft unions. These craft unions, for instance the Fire Brigade Union, Bakers Unions, and the Associate Society of Locomotive Engineers and Fireman, until the rapid reversal of the forward march in the eighties, exerted considerable control over the labour market as they were able to regulate the supply of labour by regulating entry into their specific craft. Although this still exists in part, the trajectory of trade unions in the United Kingdom is towards general unions, for instance UNISON, Unite, and GMB, meaning that the labour aristocracy may continue to decline.

Organised labour means workers who are part of labour organisations, most importantly trade unions, while unorganised labour means those who are not. Even within the distinction of organised labour there are further divides: some trade unions may be open (general) while others may be closed (craft) unions. Not all these categories are mutually exclusive, and some will go hand in hand, for instance a labour aristocracy operating a closed union, but they are useful distinctions to keep in mind. Thus, it is evident that even the supposed traditions of a class are complex and varied, and this is before the splits between the workplace, the home, and public life are taken into account. Therefore, ascribing one group as the sole TWC, without accounting for the different social relationships that define this class, is a flawed exercise.

While it is important to note the distinctions between different types of working-class existence, it is equally important not to become lost in these distinctions. Edward Thompson argues that:

‘“Working classes” is a descriptive term, which evades as much as it defines. It ties loosely together a bundle of discrete phenomena. There were tailors here and weavers there, and together they make up the working classes.”12

This is where it is important to draw the distinction between the objective situation of a class and a groups’ subjective awareness of its situation. While it is true that many people consider themselves/are considered to be part of the TWC and, if coverage of the 2019 General Election is to be believed, voted for the party they believed best represented them, their relations to production have too little in common for them to be considered a class.13 The act of self-identifying as part of a class is not enough in and of itself to qualify for class membership.

As highlighted above, the historical construction of the ‘traditional’ omits many groups of people from working-class history, and particularly women, immigrants, and the urban working-class. It also too often ignores the traditions of workers’ organisation. All of these have been integral to the English working-class since its inception. Even if these omissions are not conscious or deliberate, they are significant. Too often the historical and current importance of these groups is not sufficiently expressed. It is not enough to avoid their exclusion, instead their historical significance should be actively highlighted.

Tradition’s Omissions:

A women’s place?

Too often there is the underlying assumption that women do not work and are exclusively what Richard Hoggart termed “the pivot of the home”.14 While the significance of working-class women to the family and the home, either as single mothers or as part of a partnership, is often noted, their status as workers is too often ignored. While the unpaid domestic labour of working-class women has, as noted by Lisa Vogel, been integral to the social reproduction of the working-class, the nature of this socially reproductive labour is disputed. Some, such as Vogel, argue that it is ultimately unproductive labour as it does not generate surplus-value, while others such as Sylvia Federici and Alessandra Mezzadri have exposed the potential limitations in Marx’s theory of value and argued that, in Federici’s words, ‘those who produce the producers of value must be themselves productive of that value’.15 The scope of this debate, interesting and challenging as it is, is beyond the parameters of this article.16 What I want to highlight is that working-class women, as well as undertaking vital unpaid domestic labour, have always functioned as conventional workers selling their labour power.

Work is a fundamental part of working-class life; as long as the working-class has existed working-class women have been workers. However, working-class women have often been much more limited in how, and the extent to which, they sell their labour power. They have typically had to navigate more complex and arduous relationships with production and capital. This makes their contribution to the development of the working-class particularly important as it adds a different and more complicated dimension to the formation of this class.

Perhaps the underlying assumption about working-class women and work has not been helped by famous historical texts, such as The Making of the English Working-Class, which fail to adequately account for the role of women in this process. For example, in the nineteenth century many working-class women worked as domestic servants. Laura Schwartz notes how research conducted by Leonore Davidoff demonstrates that a gendered division of labour relegated women’s economic activity to a theoretical private sphere, resulting in domestic labour (the majority of which was female) being devalued and regarded as unproductive, even though this low paid domestic labour was integral to nineteenth century capitalism and social reproduction.17 Schwartz also highlights that servants were excluded from Marx’s analysis of contemporary capitalism. Since their work was viewed as unproductive they were considered unimportant to the development of the working-class. 18

However, women were not solely engaged in domestic labour, whether paid or unpaid, in the nineteenth century. Many women and children worked in the textile industry, and still do today in sweatshops across the globe. In this industry, they had a more straightforward relation to production and the creation of surplus value. The experiences of these women are still often ignored in the descriptions of the TWC, which consistently situates women in the home, and focusses on an almost fetishised construction of the male worker. Textiles as an industry is an interesting case study. It is the one major industry from which women (and children over 12 with a ‘leavers certificate’) were not excluded by male unions/legislative provision, perhaps because of its relative ‘domestic’ nature.

Women’s work being theoretically, if not practically, relegated to the home (despite the brief interruption of the First World War) continued into the twentieth century. This does not mean that women did not work, just the opposite in fact. Dolly Wilson points out that, prior to the growth of part-time women workers in the post-war period, as many as 40% of women in Edwardian working-class communities were engaged in petty home-based capitalism.19 Their economic activities included washing, child-minding, and selling homemade food and drink, and were part of ‘the underground economy of sweated labour, casual and home-work’.20

Even though in the post-war period the work done by working-class women has become more visible, as some moved away from the shadow economy and into the recognised labour market, they are not typically recognised as working-class workers. This is despite active participation in the labour movement, and multiple high profile industrial disputes, the most famous of which are probably the successful 1968 Ford sewing machinists strike that lead to the 1970 Equal Pay Act, and the unsuccessful Grunwick dispute in 1976.

Although, as Johnathan Moss notes, women ‘presented themselves on the labour market on different terms to men’, they have still indisputably been an active part of the working-class and organised labour since 1945. Any conception of the working-class that does not take into account that not only have working-class women always worked, but also that they have often experienced distinct and more arduous conditions of employment, is counter-productive to recognising the many facets of working-class existence and experiences. 21 Moss also argues that labour force participation in this period ‘was often experienced or viewed as claim to political citizenship’. Just as engaging in industrial disputes proved that working women were political citizens, it can also be interpreted as demonstrating that women were fully conscious and active members of their class, as this participation highlights that industrial militancy was not just the preserve of men22

The tradition of working-class women working has continued in the twenty-first century, their position in the labour market has become more entrenched, so it is odd that they are often tacitly excluded from the descriptions of ‘traditional’ workers. The improved (though by no means perfect and now worsening) position of working-class women in the labour market is the outcome of an important tradition of struggle. Women are also now more established in the labour movement and are responsible for 57% of Britain’s trade union membership.23Indeed, in the sixties and seventies they accounted disproportionately for the rapid increase in union membership. However, an indication of how far they still have to go is that UNISON, with a membership of 80% women, has only just elected its first female general secretary: Christina McAnea, who was born into a working-class family in Glasgow.

Furthermore, the current pandemic has highlighted the amount of working-class women that are key workers (largely as a result of women being concentrated in frontline industries, such as health, childcare, and education).24 However, the pandemic has also highlighted the precarious nature of female employment as during the first wave of the pandemic, ‘more working class women than men or women in middle-class jobs saw their already shorter weekly hours cut back’.25 Thus, while it is important to recognise that working-class women will often have a different relationship to production than their male counter-parts, they have traditionally been engaged in one form of production or another and their work has, and continues, to be a vital component of working-class self-making.

Location, Location, Location

Situating the traditional working-class exclusively in ‘left behind’ towns in the North, Midlands, and Wales is also historically inaccurate. Firstly, ‘left behind’ areas also exist in the south. Secondly, doing so ignores the material conditions of the working-class located in the cities, which are traditionally as much a part of the working-class as their counterparts in provincial towns or villages. Hobsbawm notes the centrality of cities to the development of the working-class in the late nineteenth century, as they were the site of ‘the rise of large industrial concentrations where none had existed before’.26 This is not to say that the urban working-class were the sole proprietors of their class’ existence, as Hobsbawm also notes that in the same period of substantial urban growth the number of miners more than doubled. Many of these miners would not have lived in cities but in towns and villages.

However, the ‘traditional’ descriptor acknowledges the significance of towns and villages but ignores the importance of cities. This is despite industry being integral to the growth (and in some cases, existence) of cities across Britain. For instance, Middlesbrough housed industry based on iron and later chemicals, Manchester was a centre of cotton merchanting (and surrounded by a ring of cotton producing towns such as Bolton and Bury), Bradford was built on its wool industry, Sheffield and Merthyr Tydfil were founded on the steel industry, Glasgow became synonymous with shipbuilding, while London’s East End, prior to the expansion of its financial services, was a heartland for manual labour – also centred around shipping.

An important difference between the contemporary working-class and that of the nineteenth century, is that whereas in the nineteenth century many villages, towns, and cities provided opportunities for work (though the work itself was dangerous and physically exhausting), now it is predominantly cities that house new job-creating industries. As capitalism has developed so too have the types of jobs available to working-class people: delivery work, call centres, and fast food have all become typical working-class jobs. Although these jobs will be substantially different from those available to the working-class in the nineteenth century, the conditions of employment are increasingly similar as a result of the growth of the gig economy and erosion of organised labour.27

However, a key difference is that much of this labour, particularly that which is contracted and administered via online platforms, is fragmented. This is helping to create a more atomised working-class, whose work is less social. The consequence of less social processes of production is that this class may find it harder to exercise its power as a collective because the process of ‘socialisation’, that Marx described as an integral part of capitalism and vital to class organising, are absent or minimal.28 In this sense contemporary labour strongly contrasts with the collective industrial processes of the nineteenth century. Although this is not true for all the working-class jobs provided by the modern economy, it is potentially significant for the future of this class.29 The deciding factor as to whether there are different relationships between workers will be the extent to which workers exercise their agency and organise themselves. Only time will tell whether workers will form new social relations with each other and create a collective identity in spite of, indeed in opposition to, the nature of their work. This will be one of the key determinants of the working-class’ future in the twenty-first century.

Regardless of the future alienating and de-socialising effects of working-class work what is evident is that cities are the centre of most working-class people’s relations to production and consumption. Perhaps it is this that is the problem, and why the term TWC strikes such a chord in the ‘left behind’ towns. It is these places that are characterised by the forced deindustrialisation of the mining and manufacturing sector. Consequently, they have undergone significant demographic changes in the last thirty years, not least in youth emigration, which also indicates that the experiences of class will vary considerably depending on age.30 In contrast to cities, these towns are not occupied by multigenerational working-class communities, but by their ghosts. They are places where, borrowing once more from Marx, the memory of life prior to de-industrialisation and the ‘tradition’ of dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living as a misremembered past.

The collective sense of longing is even more important when it is considered what many of these towns have now become. They have not become centres of the lumpen proletariat. Instead, capitalism has filled the vacuum and made use of the surplus labour power.31 The larger mining towns (not the pit villages) and ex-industrial centres now house many new industries, for instances delivery work, warehouses, and call centres.32 As noted above, this work is not as innately social as the ‘traditional’ work of mining and the factory production line, and does not give the town the same sense of identity and community. Thus, the current state of working-class existence in former industrial/mining communities is not part of a tradition. It is a consequence of the death of tradition. The class was permanently estranged from the work that defined it.

One hundred percent Anglo-Saxon, with perhaps just a dash of Viking

Just as women are ignored, and the experience of the urban working-class marginalised, so too is the role of racialised immigrants in shaping working-class history. While the issue of race and racialisation is inexorably tied to migration, it is not only relevant to migration and is not unique to the history of the working-class. The aim of this section is primarily to focus on the impact of migration as the arrival of additional, often racialised, labour that has, through its own organisation and self-making, been integral to the development of the English working-class. The English working-class has never been completely British and has always benefited from substantial immigration. Satnam Virdee points out that the ‘English working class in particular was a heterogeneous, multi-ethnic formation from the moment of its inception’.33 However, many common formulations of the TWC present it as not just white, but as something distinctly British, the understanding of which seems to be based on a historically grotesque conception of the Anglo-Saxon.

The integration of immigrants into the working-class, and society, has never been seamless and they have often been faced with racialised discrimination by local communities and the state. The struggles of this racialised labour has defined the contours of the working-class in the face of oppression from society and the state. A reality once more underscored by the recent expulsion of members of the Windrush Generation in 2018.

The struggle of minorities to be granted the same rights as part of British society and the English working-class, is one of the fundamental processes of the dialectic of working-class self-making. For, on one side, there are groups and forces that attempt to force migrant workers out of the working-class or the labour movement, on the other side there are the migrant workers who, with help from supporters and capitalism’s need for labour power, fight to root themselves in the English working-class. Virdee argues that it was precisely because of their status as racialised outsiders, and their need to assert collective action, that migrants, ranging from Irish Catholics in the nineteenth century to Asian immigrants in the late twentieth century, were able to effect significant changes in the condition of the working-class.

An example of this is the process, set-out by Virdee, in which he details how black members of the working-class, and their struggles, became an important part of the considerations of organised labour in the nineteen seventies and resulted in the articulation of a distinct anti-racist class consciousness in many of the industrial disputes of that decade.34 Although I think that Virdee’s presentation of industrial disputes is too schematic, and the apparent ideological left wing surge in organised labour is overstated, he irrefutably demonstrates that the agency of racialised labour, and its relations to the wider labour movement, are intrinsic components of the self-making of the English working-class.

Racialised immigrant labour influencing the lives of the wider working-class is also evident at the start of this class’ existence. When the working-class came into existence in the nineteenth century much of this immigration was Irish, to the extent that Thompson describes Irish immigration as integral to the making of the English-Working Class.35 Virdee, demonstrates how the Catholic Irish were quickly racialised. This occurred not just in the nineteenth century but also in the twentieth during the inter-war period.36 Despite being racialised and discriminated against, Irish Catholics were fundamental in negotiating with the Admiralty for improvements in pay and conditions and heavily involved in the corresponding societies which provided ‘artisans, shopkeepers, mechanics and general labourers’ – the heroes of Thompson’s incipient working-class – with substantial support.

One of the main charges brought against immigrant labour, and one that fuels its racialisation, is that it is unskilled and drives down the price of indigenous labour, therefore acting as a reserve army of labour and impoverishing the class as a whole. This is often said to have had a particular grievous impact on the TWC.37 This claim is spurious. Thompson notes that in the nineteenth century Irish labour was not particularly cheaper than its English counterpart.38 In fact the Irish often functioned as the ‘unskilled’ labour compared to the ‘skilled’ labour of their English counterparts, in this sense the presence of the Irish may actually have increased the price of English labour, and at the very least allowed English labour to take on what were often more favourable jobs.39 Equally, the substantial immigration from Europe and former British colonies in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War would not have driven down wages overall because there was an acute labour shortage, and the British state was actively recruiting immigrant labour. What is more likely to have happened is that non-white labour will have been artificially devalued. Furthermore, the immigration that was a result of Britain’s membership of the European Union is equally unlikely to have depressed incomes.40

The tensions and racialisation that arise over immigrant labour demonstrate how a class is never completely homogenous and the experiences of its members will vary. However, migrant labour is undisputable part of the English working-class. While some of its experiences will be distinct from other fractions within this class, in practice it does not exist as an isolated group and labours within the same relationships of production. The work performed by the English working-class has depended on the work of immigrants. Any actual traditional working-class must not only take account of the existence of immigration but also of the efforts and struggles of these immigrants to establish their legitimacy and right to exist and work in British society.

Women, immigrants, and the urban working-class chart a course through the history of the English working-class and their tradition of workers’ organisation, as an expression of a class moving from – in the words of Marx – a class in itself to a class for itself.

Conclusion

The above analysis has attempted to provide a brief, and by no means conclusive, sketch of the historic aspects of the self-formation of a multi-faceted class. There are many people who will feel a genuine connection to the conception of the TWC. However, I think that were this term applied with greater historical accuracy rather more people would feel represented by it. Working-class history has affected, and been affected by, women, immigrants, and members of the urban working-class, just as much as any other members of this class. It is important to recognise these traditions, and the various relationships that they entail. Equally, it should be recognised that the rhetorical potency of the term TWC exists precisely because so many working-class traditions have been lost or removed from history. It is an expression of a sensation of loss and awareness of declining material conditions. While the term is often a misremembering of the past it needs to be understood that this misremembering has precisely been enabled by the silencing of historical actors and the destruction of working-class institutions to the extent that large segments of the working-class have been alienated from their own history.

Only by recognising and celebrating these elided historical experiences can any accurate notion of tradition begin to be constructed. This is of paramount importance. If the working-class is to thrive and reverse the decline of its material conditions, then an accurate version of its history needs to be formulated and understood. The past, or rather how people interpret and understand the past, is a powerful source of inspiration and motor for change. In order to affect the right sort of change, and one that is beneficial to this class, it is vital to ensure that an accurate rendition of the past is celebrated.

I have not included any significant analyses of working-class organisations and movements, for instance the trade union and co-operative movements, because the focus of this article was intended to be the categories of individuals, not institutions, that the TWC excludes. As it happens, I do think that the TWC excludes working-class organisations and their integral impact on working-class history. For instance, successes such as the Mechanics’ Institutes of the nineteenth century, the establishment of Ruskin and Plater, and the original iteration of History Workshop are too often forgotten despite them being evidence of the working-class’ capacity for educational self-improvement.

Equally, the fundamental impact that the trade union movement has had on the relations of production cannot be understated. Achievements of sick pay, the eight-hour day, the weekend, paid holiday and parental leave, the minimum wage, protection from discrimination, and equal pay have fundamentally transformed many workers’ relationship with capital. Furthermore, the creation of the Labour Party, born out of the Labour Representation Committee, as a direct product of the trade union movement has also fundamentally shaped the course of British history. While the Labour Party, much like organised labour, cannot claim to have found universal acclaim with the English working-class, the impact its presence has had on this group is as undeniable as is the fact that it would not exist without organised labour. All the above institutions are part of a working-class tradition of establishing movements and organisations for the sake of class advancement and enrichment, but they are seldom incorporated into the popular understanding of working-class tradition.

Just as it is obligatory to investigate the notion of tradition and identify what it includes and excludes, it is just as necessary to recognise what has genuinely changed. For instance, the demographic changes in many of Britain’s communities, the new industries provided by contemporary capitalism, and the declining conditions of employment. These changes lend credence to the superficial construction of the TWC. Classes are in flux and constantly subjected to processes of making and un-making.41 As it stands, the conception of ‘tradition’ does not tell us anything about this class’ relationship to production or other classes, nor does it provide genuine insights into the relationships that constitute the inner-workings of this class. Whereas if we focus on what it omits, we can see that women and immigrants typically experience different relations to production and other members of this class, the same is true of the working-class who reside in cities and are exposed to the latest of capitalism’s machinations.

Meanwhile, the decline of organised labour means that the working-class is now in a more exploitative relationship with capital. Without these qualifications the TWC is a hollow shell of a concept, which does not allow us to compare an accurate construction of the past with the present. The TWC is what Benedict Anderson described as an imagined community. It is a relatively recent invention that makes claims to historical heritage, and its rhetorical potency severely contrasts its intellectual poverty.42

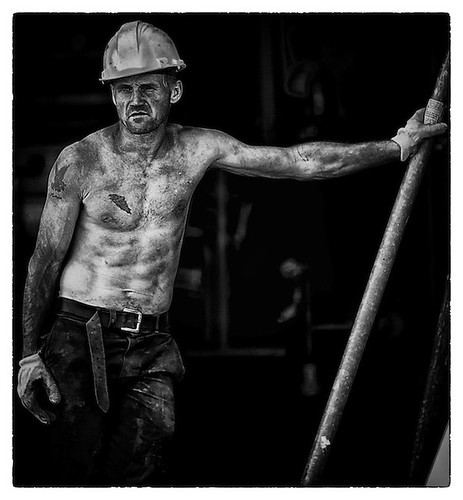

Image “Working Class Hero (Revisited)” byFouquier ॐ is licensed underCC BY-NC-ND 2.0

References

Adler, Paul 2007, ‘Marx, Socialisation and Labour Process Theory: A Rejoinder’, in Organisation Studies, Volume: 28, Issue:9, pp.1387-1394

Anderson, Benedict 2006, Imagined Communities, (London: Verso)

Beatty, Christina, Gore, Anthony, and Forhergill, Stephen, The state of the coalfields 2019: Economic and social conditions in the former coalfields of England, Scotland and Wales, pp.21-25, available at: https://shura.shu.ac.uk/25272/1/state-of-the-coalfields-2019.pdf

Berry, Craig 2017, The proletariat problem: general election 2017 and the class politics of Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn, available at:http://speri.dept.shef.ac.uk/2017/07/05/the-proletariat-problem-general-election-2017-and-the-class-politics-of-theresa-may-and-jeremy-corbyn/

Bottomore, Tom, Laurence Harris, Miliband, Ralph, and Miliband Kiernan, V.G.1994, A Dictionary of Marxist Thought, Oxford: Blackwell.

Eidlin, Barry 2020, ‘Why Union are Good- But Not Good Enough’, Jacobin, available at:https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/01/marxism-trade-unions-socialism-revolutionary-organizing,

Elledge, Jonn, ‘How demographics explains why northern seats are turning Tory’, available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/staggers/2019/12/how-demographics-explains-why-northern-seats-are-turning-tory

Embry, Paul 2019, ‘Why does the Left sneer at the traditional working class?’ UnHerd, available at:https://unherd.com/2019/04/why-does-the-left-sneer-at-the-traditional-working-class/

Federici, Silvia, ‘Social reproduction theory: History, issues and present challenges’, Radical Philosophy 2.04, (Spring 2019), pp. 55-57.

Ford, Robert, and Goodwin, Matthew 2016, Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin, ‘Different Class? UKIP’s Social Base and Political Impact: A Reply to Evans and Mellon’, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 69, Issue 2, April 2016, pp. 480–491.

Greeson, Matthew 2012, ‘Thatcher and the British Election of 1979: Taxes, Nationalization and Unions Run Amok’, Colgate Academic Review, Volume 4, Article 3, pp. 4-12

Hobsbawm, Eric, ‘The Labour Aristocracy in Nineteenth-century Britain’, in Labouring Men: Studies in the History of Labour, (London: Weidenfeld, 1964)

Hobsbawm, Eric 1983, ‘Inventing Traditions’, in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (eds)The Invention of Tradition, pp.1-15, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hobsbawm, Eric 1984, Worlds of Labour, London: George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Limited.

Hoggart, Richard 1957, The Uses of Literacy, London: Chatto and Windus.

Jones, Owen 2016, There’s a fight over working-class voters. Labour must not lose it, available at:https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/oct/06/fight-working-class-voters-labour

Lyonette, Clare and Warren, Tracey 2020, Are we all in this together? Working class women are carrying the work burden of the pandemic, available at:https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/covid19/2020/11/12/are-we-all-in-this-together-working-class-women-are-carrying-the-work-burden-of-the-pandemic/

Thoburn, Nicholas, ‘Difference in Marx: the lumpenproletariat and the proletarian unnamable’ Economy andSociety Volume 31 Number 3 August 2002: 434–460, pp. 443-444

Marx, Karl 1992, Capital Volume Three, London: Penguin.

McIlroy, John 2014, ‘Marxism and the Trade Unions: The Bureaucracy versus the Rank-and-File Debate Revisited’, Critique, 42:4, pp. 497-526.

Mezzadri, Alessandra, ‘On the value of social reproduction: Informal labour, the majority world and the need for inclusive theories and politics’, Radical Philosophy 2.04, (Spring 2019), pp.33-41

Murray, Toney 2016, No reason to doubt No Irish, no blacks signs, The Guardian: available athttps://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/28/no-reason-to-doubt-no-irish-no-blacks-signs

Moss, Jonathan 2019, Women, workplace protest and political identity in England, 1968-85, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Mulholland, Marc 2009, Marx, the Proletariat, and the “Will to Socialism”’, in Critique, 37:3, pp. 319-341.

O’Connor, Sarah, ‘ “Lazy” Britons aren’t the reason for the UK migrant workforce’, Financial Times, available at:https://www.ft.com/content/eb5e3bd7-c8bf-4934-b60e-0e49152183a5

Partington, Richard 2019, ‘Gig economy in Britain doubles, accounting for 4.7 million workers’,The Guardian, available at:https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jun/28/gig-economy-in-britain-doubles-accounting-for-47-million-workers

Price, Richard, ‘Review: the Segmentation of Work and the Labour Aristocracy’, Labour / Le Travail

Vol. 17 (Spring, 1986), pp. 267-272

Savage, Mike, et al. 2013, ‘A New Model of Social Class? Findings from the BBC’s Great British Class Survey Experiment’, Sociology, 47(2), 2013, pp. 219-250.

Schwartz, Laura, 2019, Karl Marx and Domestic Servants: A historical overview of Marx’s and Marxist thinking on domestic workers, reproductive labour and class struggle, available at:https://www.academia.edu/42641042/Karl_Marx_and_Domestic_Servants_A_historical_overview_of_Marxs_and_Marxist_thinking_on_domestic_workers_reproductive_labour_and_class_struggle

Smith, Dave 2020, ‘Cheap migrant labour is a myth and so is its effect on productivity’, The Times, available at:https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/cheap-migrant-labour-is-a-myth-and-so-is-its-effect-on-productivity-hv3s8vt8x

Thompson, Edward 1964, The Making of the English Working Class, New York: Pantheon Books.

Thorpe, Keir 2000, ‘Rendering the Strike Innocuous’: The British Government’s Response to Industrial Disputes in Essential Industries, 1953-55’, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Oct. 2000), pp.577-600.

Toscano, Alberto and Woodcock, Jamie 2015, “Spectres of Marxism: A Comment on Mike Savage’s Market Model of Class Difference”, The Sociological Review, 2015, available at:https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1111/1467-954X.12295

Unknown 2019, Trade Union Membership, UK 1995-2019: Statistical Bulletin, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/887740/Trade-union-membership-2019-statistical-bulletin.pdf

Virdee, Satnam, ‘A Marxist Critique of Black Radical Theories of Trade-union Racism’, Sociology, August 2000, Vol. 34, No. 3 (August 2000), pp. 545-565

Virdee, Satnam, Racism, Class and the Racialized Outsider, (London: Red Globe Press, 2014)

Vogel, Lise, Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory, (Boston: Leiden, 2013)

Walker, Martin 2012, “The Origins and Development of the Mechanics’ Institute Movement 1824 – 1890 and the Beginnings of Further Education”, Teaching in Lifelong Learning 4(1), available at: https://www.teachinginlifelonglearning.org.uk/article/id/136/

Wilson, Dolly 2006, ‘A New Look at the Affluent Worker: The Good Working Mother in Post-War Britain’, Twentieth Century British History, 2006, vol.17(2), pp.206-229.

- 1. Some of the examples of the term from across the political spectrum are: Labour is no Longer the party of the traditional working-class, available at: https://www.economist.com/bagehots-notebook/2018/07/06/labour-is-no-longer-the-party-of-the-traditional-working-class (accessed 15.01.2021) To win back the working class we must ditch identity politics, available at: https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/f/win-back-working-class-we-must-ditch-identity-politics (accessed 15.01.2021) Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin, ‘Different Class? UKIP’s Social Base and Political Impact: A Reply to Evans and Mellon’, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 69, Issue 2, April 2016, pp. 480–491. Owen Jones, There’s a fight over working-class voters. Labour must not lose it, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/oct/06/fight-working-class-voters-labour (accessed 15.01.2021) Craig Berry, The proletariat problem: general election 2017 and the class politics of Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn, available at: http://speri.dept.shef.ac.uk/2017/07/05/the-proletariat-problem-general-election-2017-and-the-class-politics-of-theresa-may-and-jeremy-corbyn/ (accessed 15.01.2021).

- 2. Although the trials and tribulations of the British Labour Party do not have a monopoly on class discourse in the UK they still have a considerable effect its contours.

- 3. Paul Embry, ‘Why does the Left sneer at the traditional working class?’ UnHerd, available at: https://unherd.com/2019/04/why-does-the-left-sneer-at-the-traditional-working-class/, (accessed, 21.02.2021). I disagree with much of Embry’s construction of class here, but he deserves acknowledgement for putting more thought into the term ‘traditional working-class’ than most.

- 4. Mike Savage, Fiona Devine, Niall Cunningham, Mark Taylor, Yaojun Li, Johs. Hjellbrekke, Brigitte Le Roux, Sam Friedman, and Andrew Miles, ‘A New Model of Social Class? Findings from the BBC’s Great British Class Survey Experiment’, Sociology, 47(2), 2013, pp. 219-250, p.240.

- 5. Eric Hobsbawm, ‘Inventing Traditions’, in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (eds) The Invention of Tradition, pp.1-15, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), p.1.

- 6. Ibid, p.10.

- 7. Satnam Virdee, ‘A Marxist Critique of Black Radical Theories of Trade-union Racism’, Sociology, August 2000, Vol. 34, No. 3 (August 2000), pp. 545-565, p.560.

- 8. Marc Mulholland, Marx, the Proletariat, and the “Will to Socialism”’, in Critique, 37:3, pp. 319-341. Michael Simpkins’ What’s My Motivation? provides an insight into the life of an actor in a precarious labour market selling their labour power for very little.

- 9. Eric Hobsbawm, ‘The Labour Aristocracy in Nineteenth-century Britain’, in Labouring Men: Studies in the History of Labour, (London: Weidenfeld, 1964), p. 272.

- 10. Tom Bottomore, Laurence Harris, V.G. Kiernan, and Ralph Miliband (eds.), A Dictionary of Marxist Thought, (Oxford: Blackwell 1994), p. 296.

- 11. Richard Price, ‘Review: the Segmentation of Work and the Labour Aristocracy’, Labour / Le Travail Vol. 17 (Spring, 1986), pp. 267-272.

- 12. E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Pantheon Books, 1964) p.9.

- 13. A demonstration of the difficulties with identifying class membership detached from productive forces is the Guardian’s North of England Editor claiming an artisanal pizza shop owner and retired nurse unquestionably part of the same class: available at https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jul/08/imagine-the-state-wed-be-in-if-corbyn-had-been-in-charge-the-view-from-the-red-wall (accessed 15.01.2020)

- 14. Richard Hoggart, The Uses of Literacy (London: Chatto and Windus, 1957) p.16. One of the main flaws with Hoggart’s presentation of the working-class family is that it is built on the assumption of marriage; that it does not account for single parent families, even though they are an equally legitimate form of family.

- 15. Lise Vogel, Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory, (Boston: Leiden, 2013), pp. 152-154, Alessandra Mezzadri, ‘On the value of social reproduction: Informal labour, the majority world and the need for inclusive theories and politics’, Radical Philosophy 2.04, (Spring 2019), pp.33-41, and, Silvia Federici, ‘Social reproduction theory: History, issues and present challenges’, Radical Philosophy 2.04, (Spring 2019), pp. 55-57.

- 16. While the debate around whether social reproduction is productive or unproductive labour is interesting from a theoretical standpoint, I think that it does not particularly matter. The fundamental conditioning factor of the relationships that create the material reality of social reproduction is that the labour itself is unpaid and built on institutionalised social norms and is these factors that have resulted in it not being regarded as proper work and not adequately compensated/supported by the state/employers.

- 17. While the debate around whether social reproduction is productive or unproductive labour is interesting from a theoretical standpoint, I think that it does not particularly matter. The fundamental conditioning factor of the relationships that create the material reality of social reproduction is that the labour itself is unpaid and built on institutionalised social norms and is these factors that have resulted in it not being regarded as proper work and not adequately compensated/supported by the state/employers.

- 18. Ibid, p.1.

- 19. Dolly Wilson, ‘A New Look at the Affluent Worker: The Good Working Mother in Post-War Britain’, Twentieth Century British History, 2006, vol.17(2), pp.206-229, p.222.

- 20. Ibid.

- 21. Jonathan Moss, Women, workplace protest and political identity in England, 1968-85 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), p.165.

- 22. Ibid, p.164.

- 23. Trade Union Membership, UK 1995-2019: Statistical Bulletin, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/887740/Trade-union-membership-2019-statistical-bulletin.pdf (accessed 16.01.2021). This report states that women account for 3.9 million of British trade unionism’s 6.44 million members. (3.9/6.44)*100 = 57.

- 24. Clare Lyonette, and Tracey Warren, Are we all in this together? Working class women are carrying the work burden of the pandemic, available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/covid19/2020/11/12/are-we-all-in-this-together-working-class-women-are-carrying-the-work-burden-of-the-pandemic/

- 25. Ibid.

- 26. Eric Hobsbawm, Worlds of Labour, (London: George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Limited 1984), p.197.

- 27. Richard Partington, ‘Gig economy in Britain doubles, accounting for 4.7 million workers’, The Guardian, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jun/28/gig-economy-in-britain-doubles-accounting-for-47-million-workers (accessed 17.01.2021).

- 28. Paul Adler, ‘Marx, Socialisation and Labour Process Theory: A Rejoinder’, in Organisation Studies, Volume: 28, Issue:9, pp.1387-1394, p.1387.

- 29. Industries such as fast food are still part of a socialised labour process. A good example of this is McStrike. On 18 November 2019 McDonalds workers in South London commenced industrial action the latest in a series of global industrial action by fast food workers. The main demands of the strike were pay rise to £15 an hour and secure terms of employment in the form of a forty-hour week. A significant enable of this labour militancy was that the relevant workplaces were located relatively close together and that the labour itself was still a collective process.

- 30. Jonn Elledge, ‘How demographics explains why northern seats are turning Tory’, available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/staggers/2019/12/how-demographics-explains-why-northern-seats-are-turning-tory (accessed: 18.01.2021). Young people having to leave home and travel to the city looking for work is in fact one of the great traditions of working-class existence as economic necessity drives internal migration.

- 31. By lumpenproletariat I mean a group of people who exist outside typical relations of production, as is detailed here: Nicholas Thoburn, ‘Difference in Marx: the lumpenproletariat and the proletarian unnamable’ Economy and Society Volume 31 Number 3 August 2002: 434–460, pp. 443-444.

- 32. Christina Beatty, Stephen Forhergill, and Anthony Gore, The state of the coalfields 2019: Economic and social conditions in the former coalfields of England, Scotland and Wales, pp.21-25, available at: https://shura.shu.ac.uk/25272/1/state-of-the-coalfields-2019.pdf, (accessed: 09.02.2021)

- 33. Satnam Virdee, Racism, Class and the Racialized Outsider, (London: Red Globe Press, 2014) p. 162.

- 34. Satnam Virdee, ‘A Marxist Critique of Black Radical Theories of Trade-union Racism’, Sociology, August 2000, Vol. 34, No. 3 (August 2000),

- 35. The Making of the English Working Class, pp.429-437.

- 36. Racism, Class and The Racialized Outsider, pp.14-17, and Tony Murray, ‘No reason to doubt No Irish, no blacks signs’, The Guardian: available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/28/no-reason-to-doubt-no-irish-no-blacks-signs (accessed 18.01.2021).

- 37. I think that quite often distinctions of skilled vs unskilled (particularly now when skill is normally qualified by a level of qualification) are misleading and often a means of trying to control the supply and direction of labour, this also complicates the applicability of the Labour Theory of Value. A more useful way of deciding the value of labour would perhaps be to examine the use value of the products of specific labour power, though this would of course be subjective. The Making of the English Working Class, pp.433.

- 38. The Making of the English Working Class, pp.433.

- 39. A modern equivalent of this can be found in the predominantly immigrant labour that works as picking jobs in the UK’s farmer’s industry. For most indigenous workers, working as a food picker does not offer better pay to working in a supermarket or café, though for many migrant workers it offers better pay than many of the jobs in their previous country. Thus, the job of food picking is done by a majority migrant workforce, enabling the indigenous labour to seek marginally better/more enjoyable jobs, and that food prices can stay relatively low. Sarah O’Connor ‘“Lazy” Britons aren’t the reason for the UK migrant workforce’, Financial Times, available at: https://www.ft.com/content/eb5e3bd7-c8bf-4934-b60e-0e49152183a5 (accessed 11.02.2021).

- 40. Dave Smith, ‘Cheap migrant labour is a myth and so is its effect on productivity’, The Times, available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/cheap-migrant-labour-is-a-myth-and-so-is-its-effect-on-productivity-hv3s8vt8x (accessed 18.01.2021).

- 41. Alberto Toscano and Jamie Woodcock, “Spectres of Marxism: A Comment on Mike Savage’s Market Model of Class Difference”, The Sociological Review, 2015, available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1111/1467-954X.12295, (accessed 19.01.2020).

- 42. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, (London: Verso 2006), p.5.