Rohini Hensman

Preface

This article was published in the Bulletin of the Communist Platform No.2, June–September 1978, as a contribution to an ongoing discussion on trade unions that was being conducted in the Platform Group. We read and discussed Marx on trade unions and their role in determining the value and price of labour power, in converting workers from atomised individuals to an organised force, and in creating the conditions for more human relationships in the family as well as a healthier and educated working class. Among many other texts, we read Vladimir Akimov’s A Short History of the Social Democratic Movement in Russia 1904/5 and The Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (1904), and fully agreed with his critique of Lenin’s assertion in What Is to Be Done? that ‘Spontaneous development of the labour movement leads precisely to its subordination to bourgeois ideology. The spontaneous labour movement is trade-unionism, it is Nur-Gewerkschaftlerei (mere trade-unionism), and trade-unionism means the ideological enslavement of the workers by the bourgeoisie’. We read and discussed Franz Neumann’s European Trade Unionism and Politics, in which he notes the link between the triumph of democracy and the recognition of trade unions, and the inherently two-fold aim of the unions ‘not only to secure high wages and decent conditions of work for the worker but also to win for him a new social and political status,’ which is why unions have to be destroyed under fascism.

The practical outcome of these discussions in Bombay was what we called a ‘workers’ inquiry’ into the existing condition of the working class, and the formation of the Union Research Group (URG). We moved widely around Bombay and its surrounding areas meeting worker-unionists in factories and offices, bringing out a Bulletin of Trade Union Research and Information for them, and organising workshops and conferences in which the specific problems they faced and possible responses were discussed. Two of us, with help from other women activists, also conducted research into the condition of working-class women who were not employed in large-scale industry, and tried to help them to work out strategies to tackle the numerous difficulties they faced.

This still left the question of how the working class would arrive at an understanding of the ways in which capitalism itself was responsible for their problems, and how they would work out an alternative organisation of society and production. Even Akimov did not believe that trade unions could carry out a socialist revolution, nor did he deny the need for Social Democracy to accelerate the development of the proletariat’s class consciousness. But what organisational form would the transition take?

For the Bolsheviks, the revolutionary party representing the working class would capture state power, nationalise all means of production, and carry out the transition to a socialist/communist society. But, even at the time, there were dissident voices who saw this as a dangerously substitutionist strategy, which could lead the party to rule over the workers while workers themselves would continue to be exploited. Antonio Gramsci, in his article ‘Unions and Councils’ (L’Ordine Nuovo 11, October 1919), saw the factory council as an alternative to the bureaucratised trade unions and as the basic unit of the proletarian state, which could then react back on the trade unions and transform them into instruments for the abolition of all classes, which, according to him, ‘is what the industrial unions in Russia are doing’. This, too, seemed unsatisfactory, because it left out, for example, proletarian women who were not factory workers. Neither of these models suggested a procedure for ascertaining human needs, the satisfaction of which would be the goal of production in a communist society.

The analysis of the relation between theory and practice that impressed me most was Michael Vester’s The Emergence of the Working Class as a Learning Process, extracts from which were translated for us by Jairus Banaji.1 Vester makes an extremely illuminating interpretation of E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, supplemented by the work of other historians like Eric Hobsbawm as well as Marx’s own work, as cycles of struggle which were followed (especially after failure) by reflection on those struggles by leading theorists, journalists and organisers of the movement. Struggle and reflection together comprised a cycle of learning, which was followed by a new cycle of struggle informed by that learning process. Later, I used this framework to understand our work in Bombay, in the context of the labour movement in India and the response of unions around the world to globalisation, in my book Workers, Unions, and Global Capitalism: Lessons from India. A strong point of Vester’s framework is that he allows for regressive learning processes and for different sections of the working class engaging in different forms of struggle even in the same country: observations that are even more important when looking at the working class globally.

Rohini Hensman, February 2021

I

For over a century, trade unions have been the organisations by means of which the workers have fought for their interests. When we compare the condition of the working class as a time when trade unions were in their infancy with the condition of the working class where strong trade unions exist, it has to be acknowledged that they have been formidable weapons of struggle. And yet it has also become apparent that they suffer from limitations, which at certain points have led workers to reject or go beyond them in a search for alternative forms of organisation. What are these limitations and why do they exist? Can they be overcome, or are they inherent in the structure and mode of functioning of trade unions? Given both their efficacy as organs of struggleand their limitations, it is important to determine their role very exactly. It is this role which is responsible both for their historical genesis and their ultimate disappearance, and which makes it necessary for the working class both to defend them and to supersede them. We begin, therefore, with an examination of the social relations of production within which trade unions first make their appearance.

A word of explanation as to why the example of England is taken. Firstly, because this is the example used by Marx in Capital, which remains the most profound and comprehensive theoretical examination of the capitalist system which has yet been made. Therefore, the development of various theoretical points is made easier if the exposition inCapital is followed. But secondly, the example of England is used because it is the first country in which this struggle takes place. ‘Since the contest takes place in the arena of modern industry, it is fought out first of all in the homeland of that industry – England. The English factory workers were the champions, not only of the English working class, but of the modern working class in general’ (Capital Volume I, Pelican edition, p. 412). In other words, the struggle did not follow the same stages in all countries where capitalism developed: legislation which was introduced in England was introduced subsequently in other countries even without the same protracted struggle of the working class within those countries, as in the case of India. The creation of a capitalist world economy thus resulted in the generalisation not only of capitalist relations of production, but also of the gains of the working class. As Marx puts it, the English factory workers were the champions not only of the English working class but of the modern working class in general; their gains were the gains of the working class of the whole world, and we therefore examine their history as an integral part of the history of the international working-class movement.

II

The working day of the wage-labourer is divided in two portions. In the first, necessary labour is performed – labour whose equivalent in value is paid to the labourer as wages. The second portion is characterised by the performance of surplus labour, and the value created in this time is appropriated by the capitalist without equivalent. The labourer sells labour-power to the capitalist for the length of the whole working day, and receives in return value produced in the necessary labour-time. According to the laws of commodity production and exchange, what is sold must be equivalent in value to what is received in exchange. Hence the struggle over the value of labour-power is in practice a struggle over the length of the working day on one side, and the quantity of wages (the necessary labour-time) on the other. Less obviously, it is also a struggle over the intensity of work. For an increased intensity of work means an increased rate of consumption of labour-power, which must be compensated either by a reduction in the length of the working day, or by an increase in wages, if the price of labour-power is not to fall. A further complication is the fact that the value of labour-power is itself a variable quantity. Thus, the struggle of the working class over the value of labour power is a struggle both to determine the value of labour-powerand to prevent its price from falling below this value, and this in turn is achieved by regulating the length of the working day, the intensity of work and the level of wages.

From the standpoint of the capitalist, on the contrary, the aim is the maximum production of surplus-value, and Marx distinguished two major forms in which this could be achieved. The first is the production of absolute surplus-value. ‘The prolongation of the working day beyond the point of which the worker would have produced an exact equivalent of the value of his labour-power, and the appropriation of that surplus labour by capital – this is the process which constitutes the production of absolute surplus value’ (Capital Vol I, p. 645). Although he states that ‘the production of absolute surplus value turns exclusively on the length of the working day’ (p. 645), it is apparent it can be increased in other ways also. A prolonged depression of wages which leads to their new average level being accepted as the value of labour-power would lead to a shrinking of the necessary labour-time and an extension of the surplus labour-time without either a lengthening of the working day or any technical change. Intensification of labour, too, if it becomes accepted and is not compensated by a shortening of the working day or an increase in wages, would lead to an increase in absolute surplus-value production. But the length of the working day remains a crucial area around which struggle takes place.

All three methods of absolute surplus-value production increase the quantity of surplus-value (s) relative to the variable capital paid out as wages (v), and thus increase the rate of surplus-value (s/v). This increase is accompanied by a deterioration in the condition of the working class, either through a fall in their living standards, or through more intensive or extensive exploitation of their labour-power.

The second and higher mode of surplus-value production is relative surplus-value production. ‘The production of relative surplus value,’ writes Marx, ‘completely revolutionises the technical processes of labour and the groupings into which society is divided’ (p. 645). In order that relative surplus-value should be produced, ‘the rise in the productivity of labour must seize upon those branches of industry whose products determine the value of labour-power, and consequently either belong to the category of normal means of subsistence, or are capable of replacing them’ (Capital Vol. 1, p. 432). The same effect ‘is also brought about by an increase in the productivity of labour, and by a corresponding cheapening of commodities, in those industries which supply the instruments of labour and the material for labour, i.e. the physical elements of constant capital which are required for producing the means of subsistence’ (p. 432). The effect of these changes in productivity is that the same quantity of means of subsistence can be produced with less socially necessary labour than before, and consequently its value falls so that less of the working day has to be spent in producing value equivalent to it. Here, too, the surplus labour-time is increased at the expense of the necessary labour-time without any extension of the working day. But there is no fall in living standards: since the commodities necessary for the reproduction of labour-power have become cheaper, a lower wage can buy the same quantity of commodities as before, or possibly even more. Thus, the production of relative surplus-value by itself, although it increases surplus-value relative to variable capital and thus the rate of surplus-value, does not result in the deterioration of the condition of the working class.

III

The struggle over the value of labour-power is as old as capitalism itself, and can be divided into three major phases. The first is the period of ‘so-called primitive accumulation’, the period in which the proletariat is first formed. The process is a violent and bloody one, for this class of independent producers turned proletarian has yet to be made to accept the discipline of the capitalist enterprise. Marx writes,

The class of wage-labourers, which arose in the latter half of the fourteenth century, formed then and in the following century only a very small part of the population, well protected in its position by the independent peasant proprietors in the countryside and by the organisation of guilds in the towns. Masters and artisans were not separated by any great social distance either on the land or in the town. The subordination of labour to capital was only formal, i.e the mode of production itself had as yet no specifically capitalist character. The variable element in capital preponderated greatly over the constant element. The demand for wage-labour therefore grew rapidly with every accumulation of capital, while the supply only followed slowly behind. A large part of the national product which was later transformed into a fund for the accumulation of capital still entered at that time into the consumption-fund of the workers. (Capital Vol. 1, p. 900.)

With the balance of forces so decisively weighted in favour of the proletariat, the state had to step in on the side of capital. First and foremost, it was a question of increasing the supply of labour-power, that is, not only of expropriating the direct producers but of ensuring that they entered the wage-labour force instead of becoming beggars, robbers or vagabonds. Accordingly, legislation was passed to this end; vagabondage was to be punished by whipping, branding, ear-clipping, slavery, imprisonment and execution. ‘Thus were the agricultural folk first forcibly expropriated from the soil, driven from their homes, turned into vagabonds, and then whipped, branded and tortured by grotesquely terroristic laws into accepting the discipline necessary for the system of wage-labour’ (Capital Vol. 1, p. 899).

Secondly, it was necessary to drive down wages, and, here too, legislation was enacted from the fourteenth century onwards, forbidding the payment of wages above the statutory limit. ‘It was forbidden, on pain of imprisonment, to pay higher wages than those fixed by the statute, but the taking of higher wages was more severely punished than the giving of them… The spirit of the Statute of Labourers of 1349 and its offshoots shines out clearly in the fact that while the state certainly dictates a maximum of wages, it on no account fixes a minimum’ (Capital Vol. 1, p. 901).

Thirdly, the enactment of legislation compulsorily prolonging the working day also began in the fourteenth century. ‘Of course,’ Marx remarks, ‘the pretensions of capital in its embryonic state, in its state of becoming, when it cannot yet use the sheer force of economic relations to secure its right to absorb a sufficient quantity of surplus labour, but must be aided by the state – its pretension in this situation appear very modest in comparison with the concessions it has to make, complainingly and unwillingly, in its adult condition’ (Capital Vol. 1, p. 382). Nonetheless, modest though it appears by comparison with its later exactions from the working class, capital initiates the struggle over the length of the working day with this legislation.

Marx refers to this period as one of formal subsumption of labour-power to capital, i.e. the technical conditions of production are not transformed but remain the same as before. Thus, the only means of extracting surplus-value is through absolute surplus-value production, and all the legislation referred to above is directed to this end. Firstly, against those who are not disposed to produce surplus-value at all, to force them to become wage-labourers, i.e. to produce absolute surplus-value. Secondly, to increase the production of absolute surplus-value by driving down wages, thus increasing surplus labour at the expense of necessary labour. And thirdly, to increase absolute surplus-value production by extending the working day. During the period of the formation of the working class, when it has not come to accept capitalist discipline as the order of things, the state comes to the rescue of the individual capitalist, prescribing by law the necessity for the dispossessed to produce surplus-value at a sufficient rate to allow the accumulation of capital.

The resistance of the workers to being totally subordinated to the needs of capital lasts right up to the advent of large-scale machine industry. Even in the period of manufacture,

the full development of its own peculiar tendencies comes up against obstacles from many directions… Since handicraft skill is the foundation of manufacture, and since the mechanism of manufacture as a whole possesses no objective framework which would be independent of the workers themselves, capital is constantly compelled to wrestle with the insubordination of the workers… Hence the complaint that the workers lack discipline runs through the whole of the period of manufacture. Even if we did not have the testimony of contemporary writers on this, we have two simple facts which speak volumes: firstly, during the period between the sixteenth century and the epoch of large-scale industry capital failed in its attempt to seize control of the whole disposable labour-time of the manufacturing workers, and secondly, the manufactures are short-lived, changing their locality from one country to another with the emigration or immigration of workers. (Capital Vol. 1, pp. 489-90.)

Workers remain, in other words, the dominant element in production throughout the period of manufacture. The immanent laws of capitalist accumulation in this period, ‘its own peculiar tendencies’, cannot be realised because of the resistance of the workers; the balance of class forces is such that this resistance constitutes an insurmountable barrier to the tendency of capital to push the rate of surplus-value to its maximum upper limit.

IV

The second phase begins with the introduction of machinery, which has a devastating effect.

The instrument of labour, when it takes the form of a machine, immediately becomes a competitor of the worker himself. The self-valorization of capital by means of the machine is related directly to the number of workers whose conditions of existence have been destroyed by it… The section of the working class thus rendered superfluous by machinery, i.e. converted into a part of the population no longer directly necessary for the self-valorization of capital, either goes under in the unequal contest between the old handicraft and manufacturing production and the new machine production, or else floods all the more easily accessible branches of industry, swamps the labour-market, and makes the price of labour-power fall below its value. (Capital Vol.1, p. 557.)

Thus, machinery, by competing with the workers, compels them to compete with one another and with the unemployed, driving down the value of labour-power to the physiological minimum, and the price of labour-power even below this minimum. ‘The instrument of labour strikes down the worker’ (p. 559); by means of the machine, capital is finally able to batter down the resistance of the workers and thus to realise for the first time its own immanent laws of motion. ‘Machinery does not just act as a superior competitor to the worker, always on the point of making him superfluous. It is a power inimical to him, and capital proclaims this fact loudly and deliberately, as well as making use of it’ (p. 562). The machine enables the capitalist to wield the power of life and death over recalcitrant workers by threatening to replace them; it is consciously used as an instrument in the class struggle. No wonder, then, that workers first turned their fury against this inanimate thing which oppressed them, and attempted to safeguard their livelihood by smashing machinery. ‘It took both time and experience,’ Marx remarks, ‘before the workers learned to distinguish between machinery and its employment by capital, and therefore to transfer their attacks from the material instruments of production to the form of society which utilises those instruments’ (pp. 554-5).

This is a strange and paradoxical result. The introduction of machinery, which revolutionises production techniques and thus makes possible the large-scale production of relative surplus-value, is the occasion not for a decrease but anincrease inabsolute surplus-value production. This compulsion to increase absolute surplus-value is felt by the individual capitalist in various ways, but the fundamental reason for it is that ‘there is an immanent contradiction in the application of machinery to the production of surplus value, since, of the two factors of the surplus valve created by a given amount of capital, one, the rate of surplus value, cannot be increased except by diminishing the other, the number of workers… It is this contradiction which drives the capitalist, without his being aware of the fact, to the most ruthless and excessive prolongation of the working day, in order that he may secure compensation for the decrease in the relative number of workers exploited by increasing not only relative but also absolute surplus value’ (p. 531). This point is expounded in greater detail in Volume III ofCapital. The rate of profit (p’), which capitalists use as an index of ‘profitability’, is the ratio of surplus-value (s) to the total capital, both constant (c) and variable (v). Surplus-value is produced by variable capital alone. Therefore, the increase in the weight of constant capital compared with variable capital, which occurs with the production of relative surplus-value, leads to a fall in the rate of profit. The increase in the rate of surplus-value (s/v) partially compensates for this fall, but cannot fully do so. (See pp. 530-1 ofCapital Vol. I, also Ch.13, especially p. 222, ofCapital Vol. 3, Moscow edition.) Hence the compulsion to produce absolute surplus-value in order to compensate for the decline in the rate of profit becomes felt ‘as soon as machinery has come into general use in a given industry, for then the value of the machine-produced commodity regulates the social value of all commodities of the same kind’ (Vol. 1, p. 531).

The important point is that the compulsion to produce absolute surplus-value by no means ceases when relative surplus-value begins to be produced. On the contrary, this compulsion on the capitalist class is a constant one and becomes an over-riding obsession at times when the decline in the rate of profit is rapid and cannot easily be compensated in any other way. The compulsion resolves itself into the necessity to prolong the working day, reduce wages and intensify labour, since ‘a prolonged working day (or a corresponding increase in the intensity of labour) and a fall in wages… increase the amount, and thus the rate, of surplus value by increasing the production of absolute surplus value’ (Capital Vol. 3, pp. 51-2).

For some reason, Marx does not in Volume 1 consider the increase in absolute surplus-value production which results from the lowering of the value of labour-power through the reduction of the commodities socially accepted as being adequate for subsistence, although this is not a phenomenon which falls outside the assumed framework of a schema within which all commodities sell at value. Yet, clearly, this is the process he is describing when he writes that ‘In the period between 1799 and 1815 an increase in the prices of the means of subsistence led in England to a nominal rise in wages, although there was a fall in real wages, as expressed in the quantity of the means of subsistence they would purchase’ (p. 665). And again, ‘it is apparent that the piece-wage is the form of wage most appropriate to the capitalist mode of production… In the stormy youth of large-scale industry, and particularly from 1797 to 1815, it served as a lever for the lengthening of the working day and the lowering of wages… We find documentary evidence of the constant lowering of the price of labour from the beginning of the Anti-Jacobin war. In the weaving industry, for example, piece-wages had fallen so low that in spite of the very great lengthening of the working day, the daily wage was then lower than it had been before’ (pp. 697-8). It is evident that what is being referred to is not a mere temporary or sectoral decline in wages, a fall of the price of labour-power below its value, but a secular decline in the value of labour-power itself. What is happening here is that the value of labour-power becomes historically and morally determined at the lowest possible level, the physiological minimum, and the price falls even below this level. And this is achieved not by a cheapening of the means of subsistence but by a reduction in their quantity, so that the result is a catastrophic decline in living standards, malnutrition, lack of sanitation, disease and premature death.

While absolute surplus-value is increased by pushing the necessary labour-time ever lower, it is simultaneously increased by pushing the length of the working day ever higher, and this, too, is finally achieved with the birth of modern large-scale industry. ‘After capital had taken centuries to extend the working day to its normal maximum limit, and then beyond this to the limit of the natural working day of 12 hours, there followed, with the birth of large-scale industry in the last third of the eighteenth century, an avalanche of violent and unmeasured encroachments. Every boundary set by morality and nature, age and sex, day and night, was broken down. Even the ideas of day and night, which in the old statutes were of peasant simplicity, became so confused that an English judge, as late as 1860, needed the penetration of an interpreter of the Talmud to explain “judicially” what was day and what was night. Capital was celebrating its orgies’ (pp. 389-90). For capital, the answer to the question ‘What is the working day?’ is that the working day contains the full 24 hours minus the few hours of rest without which it is absolutely impossible to resume work. At a time when the working class was in no position to resist such encroachments, it was possible for the capitalists to extend the working day far beyond the maximum length that is compatible with health, converting into labour-time time which was needed for education, intellectual development, fulfilment of social functions, social intercourse, free exercise of mind and body, recreation, consumption of fresh air and sunlight, and even, to whatever extent it could, time needed for meals and sleep. Inevitably, the reproduction of labour-power was impaired and could not fully take place. ‘By extending the working day, therefore, capitalist production, which is essentially the production of surplus value, the absorption of surplus labour, not only produces a deterioration of human labour-power by robbing it of its normal moral and physical conditions of development and activity, but also produces the premature exhaustion and death of this labour-power itself. It extends the workers production time within a given period by shortening his life’ (pp. 376-7). This, too, is an increase in absolute surplus-value production by reducing the value of labour-power, for even if there is no reduction in wages, the same wage is being paid for a greater expenditure of labour-power than before. Hence, the value per unit of labour-power falls.

Thirdly, ‘that mighty substitute for labour and for workers, the machine, was immediately transformed into a means for increasing the number of wage-labourers by enrolling, under the direct sway of capital, every member of the worker’s family, without distinction of age or sex’ (p. 517). When carefully examined, it is evident that this extension of wage-labour to all members of the proletarian family involves the increased production of absolute surplus-value by a reduction of the individual wage on one side, and extension of the collective working day on the other. This becomes clear if the working-class family is considered as the unit of labour-power (see ‘Wage-Labour: The Production and Sale of the Commodity Labour-power’, reproduced in Bulletin of the Communist Platform 1). Formerly, the wages of a single worker realised the value of the labour-power of the family. Now, many wages – say, on average, four – are necessary in order to realise the value of the labour-power of the same family. Thus, each wage realises only part of the value of the labour-power of the family unit – that is, the value of the individual wage has fallen. At the same time, the amount of labour-time which the whole family must expend both in order to reproduce its own labour-power and to produce surplus value for the capitalist is multiplied several times over. ‘In order that the family may live, four people must now provide not only labour for the capitalist, but also surplus labour’ (p. 518). This means the extension of the collective working day of the family. The value of labour-power falls because the slight increase which may occur in the collective wage of the family is more than offset by the increased expenditure of labour-power which must be made in order to secure it.

The consequences of the extension of wage-labour to all members of the proletarian family combined with a maximum extension of working hours for all of them were far-reaching and drastic. One result was the destruction of family life, which led Marx and Engels to write in the Communist Manifesto of the virtual non-existence of the family amongst the proletariat. One aspect of this destruction was a further deterioration in health and living standards as the domestic labour which had previously helped to sustain the family ceased to be performed. Marx writes that ‘Compulsory work for the capitalist usurped the place, not only of the children’s play, but also of independent labour at home, within customary limits, for the family itself.Note: during the cotton crisis caused by the America Civil war, Dr Edward Smith was sent by the English government to Lancashire, Cheshire and other places to report on the state of health of the cotton operatives. He reported that… the women now had sufficient leisure to give their infants the breast, instead of poisoning them with “Godfrey’s Cordial” (an opiate). They also had the time to learn to cook… From this we see how Capital, for the purposes on its self-valorisation, has usurped the family labour necessary for consumption’ (p. 517). Even if we reject the implicit assumption that labour such as cooking has to be performed within the family, it is clear that its cessation, so long as it is not substituted by socialised labour, must lead to a deterioration in living standards. Nor can it entirely cease, since at least part of it is necessary for the reproduction of labour-power even in a stunted condition. Hence the work-load of the women, who are mainly considered responsible for the household work, is raised even above the already heavy work-load which is imposed on them at the place of work.

A second result was the brutalisation of human relationships, between men and women, adults and children, which inevitably followed from the abolition of time, leisure or conditions in which family relationships could develop. For example, an official medical inquiry in 1861 into infant mortality rates of around 25,000 deaths for every 100,000 children alive under the age of one year showed that ‘the high death rates are, apart from local causes, principally due to the employment of the mothers away from their homes, and to the neglect and maltreatment arising from their absence, which consists in such things as insufficient nourishment, unsuitable food and dosing with opiates; besides this, there arises an unnatural estrangement between mother and child, and as a consequence intentional starving and poisoning of the children’ (p. 521).

Perhaps the children who died in infancy were the luckier ones, for those who survived were subjected from the earliest possible age to monotonous and unremitting toil, wretched living and working conditions and brutal ill-treatment. Under such circumstances, not only was their normal development hampered, but even their potential for development was gradually lost, so that they would never in later life be able to make up for what they had missed at this early stage. So severe was the loss in terms of capacities that even the government was forced to take notice: ‘the intellectual degradation artificially produced by transforming immature human beings into mere machines for the production of surplus value…. finally compelled even the English Parliament to make elementary education a legal requirement before children under 14 years could be consumed “productively” by being employed in those industries which are subject to the factory Acts’ (p. 523). But the implementation of this legislation at that time was so poor that it might as well not have been passed.

A fourth means of increasing absolute surplus-value production is through intensification of labour, by means of which a greater amount of surplus-value can be exacted in the same time as before because the speed of work is increased. To a limited extent, this occurred immediately after machinery was introduced as workers became more accustomed to using these new means of production. As Marx remarks,

It is self-evident that in proportion as the use of machinery spreads, and the experience of a special class of worker – the machine worker – accumulates, the rapidity and thereby the intensity of labour undergoes a natural increase. Thus in England, in the course of half a century, the lengthening of the working day has gone hand in hand with an increase in the intensity of factory labour. Nevertheless, the reader will clearly see that we are dealing here, not with temporary paroxysms of labour but with labour repeated day after day with unvarying uniformity. Hence a point must inevitably be reached where extension of the working day and intensification of labour become mutually exclusive so that the lengthening of the working day becomes compatible only with a lower degree of intensity, and inversely, a higher degree of intensity only with a shortening of the working day. (p. 533.)

Thus, it is only when the working-class movement has gained sufficient strength to win from capital a shorter working day that the real drive for intensification begins. We will therefore return to it somewhat later.

The third phase of the struggle over the value of labour-power is characterised by the struggle of the workers against their reduction to a mere means of producing surplus-value, a mere appendage of capital. The trade-union movement is the form taken by this struggle of the working class to wrest back from capital its own life, to reverse the terms on which it relates to capital – i.e. to make the production of capital a mere means of its own life, which it attempts to determine autonomously and without reference to the needs of capital. What was yielded up to capital all at once has to be won back inch by inch and by dint of bitter struggle, failure and self-education. The first step in the process is to overcome their isolation and associate together.

The first attempts of workers to associate among themselves always takes place in the form of combinations. Large-scale industry concentrates in one place a crowd of people unknown to one another. Competition divides their interests. But the maintenance of wages, this common interest which they have against their boss, unites them in a common thought of resistance – combination. Thus combination always has a double aim, that of stopping competition among the workers, so that they can carry on general competition with the capitalists… In England they have not stopped at partial combinations which have no other objective than a passing strike, and which disappear with it. Permanent combinations have been formed,trades unions, which serve as ramparts for the workers in their struggles against the employers. (Poverty of Philosophy, Moscow Edition, pp.150, 149.)

Trade unions, then, are the organisations formed by the working class as an instrument in their struggle over the value of labour-power. By combining, they are able to dictate terms of sale to the capitalists, whereas in isolation, being under the compulsion to sell their labour-power in order to live, they have to sell at any price. In practice, the struggle is concentrated around wages and the length of the working day, and therefore constitutes a fight to reduce absolute surplus-value production by these means. Through the trade-union struggle, the working class radically alters itself and circumstances. From an atomised mass, it constitutes itself as an organised force; it wins the abolition of child labour, the normal working day, wage increases which allow a raising of living standards as well as a further reduction in the collective working day, education, social welfare measures. The character of the working class is substantially altered.

First and foremost, trade unionism establishes the principle of combination as a necessity for the very survival of the proletariat. ‘If the first aim of resistance was merely the maintenance of wages, combinations, at first isolated, constitute themselves into groups as the capitalists in their turn unite for the purpose of repression, and in the face of an always united capital, the maintenance of the association becomes more necessary to them than that of wages. This is so true that English economists are amazed to see the workers sacrifice a good part of their wages in favour of associations, which, in the eyes of these economists, are established solely in favour of wages’ (Poverty of Philosophy, p. 150). The trade unions proved in practice that the particular interests of individual workers are not in conflict with those of others but can be realised only together with them, and thus firmly established the principle of solidarity. Hence solidarity, instead of being a mere means of obtaining wages, became an end in itself to such an extent that material sacrifices were willingly made in the interests of maintaining it. The first step was made towards the self-constitution of the proletariat as a class for itself, a class ready to undertake its historic tasks; and the proletariat forced bourgeois society too to record this first step insomuch as the right to form combinations was legally established.

The laws protecting child labour and ultimately abolishing it, together with laws making education compulsory for children below a certain age, had far-reaching consequences. The physical and intellectual deterioration produced by ‘transforming immature human beings into mere machines for the production of surplus value’ was stemmed and halted; although the type of education introduced still involved an enormous wastage of the capacities of proletarian children by failing to develop them, these capacities were not actually destroyed by premature wage-labour. Moreover, a real development of capacities did become possible. Apart from the limited contribution made by formal education, the time spent in play, interaction with other children, the free exercise of their muscles and imaginations, contributed significantly to the physical, intellectual and emotional development of children. The conditions for the emergence of a literate working class with a basic education, intellectuals of the working class on a mass scale, the beginnings of the abolition of the division of labour between mental and manual workers, were created by the struggle to abolish child labour and obtain an education for proletarian children. This was one way in which the trade unions combatted the production of absolute surplus-value through fighting for a reduction in the collective working day of the proletarian family.

The struggle for equal pay, legal protection, maternity benefits, etc. for female labour also had far-reaching though less unambiguous consequences. While these did not exist, the bourgeoisie had no shibboleths about the sanctity of proletarian family life, no qualms about breaking up the families of proletarians and dragging all members of them into the labour market, sexually abusing proletarian women and depriving proletarian children of parental care and affection. But, to the extent that female labour became as expensive as male labour, and, moreover, demanded extra privileges, male labour was preferred, with the result that female labour tended to be thrown out of work. This was supplemented by voluntary withdrawal as male wages were pushed up to a level where they could support a whole family. Like the withdrawal of children from the wage-labour force, this represented a reduction in absolute surplus-value production resulting from a reduction in the collective working day of the family.

On one side, this made possible the constitution of the proletarian family. The higher individual wages that made it possible for women to withdraw from wage-labour created conditions for an improvement in childcare and a partial reversal of the brutalisation of human relationships which had earlier taken place. On the other side, however, this family was burdened with all those functions in the reproduction of labour-power where it was most difficult to replace living by dead labour, and these fell mainly on the women. They therefore were compelled to work in isolation, performing work organised on an irrational, individual basis, without any social control over their hours of work, conditions of work or remuneration in the form of means of subsistence.

The proletarian family requires deeper examination from the standpoint of an understanding of the family as such. Engels’s attempt to understand this relationship by delving into the distant past bears more resemblance to mythical explanations like, for example, the one in Genesis. While the ‘original sin’ may be different – in Genesis Woman allows herself to be beguiled into eating the forbidden fruit of the tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, in The Origin of the Family she allows herself to be beguiled into withdrawing from socialised production – the ‘curse’ is much the same: she is condemned to bear children in pain and to remain subordinate to Man. If, however, ‘human anatomy contains a key to the anatomy of the ape,’ and bourgeois society, as the most developed form, allows insights into earlier forms, (Marx,Grundrisse, Pelican edition, p. 105), then it is the proletarian family which contains the key to earlier forms, not vice versa, and it is in ‘the huddled dwelling-places of the working class’ that ‘the springs of life are welling up’ (A. Kollontai, ‘Sexual Relations and the Class Struggle). Here is a family which is propertyless, divested of all ownership or possession of means of production, a family which is not in any meaningful sense a unit of production, and progressively loses its productive functions as society, through schools, laundries, pre-cooked food, etc., takes on functions previously performed in the family. Its tendency of development, therefore is towards a unit which is held together purely by the personal relationships within it, a sphere in which relationships of love can most fully and deeply be realised, in which children can first develop a consciousness of their own personalities along with the capacity to love. But capitalist relations of production constitute a barrier to the final working out of this tendency, as they also constitute a barrier to the tendency for greater and greater socialisation of labour to be carried to its limit. Capitalism imposes on the family the responsibility and labour necessary for its reproduction; also, the sexual division of labour, which impoverishes both men and women, as the mental/manual division of labour impoverishes both mental and manual workers; and as a consequence of these, a hierarchical structure where women are subordinate to men and children to adults. There results, inevitably, a corrosion and distortion of the relationships within it; and this cannot entirely be overcome without the socialisation of housework, the abolition of the sexual division of labour, and the dissolution of all relationships of domination and subordination, not from the standpoint of the bourgeois principles of formal equality and independence, but from the standpoint of the proletarian principles of solidarity, comradeship and perfectly balanced mutual dependence where affirmation of oneself is equally an affirmation of the other (Marx,Early Writings, Pelican edition, p. 277). The development by the proletariat of its own sexual morality is an important step in its formation into a class, for as Marx correctly noted, the relationship of man to woman ‘reveals in asensuous form, reduced to an observable fact, the extent to which the human essence has become nature for man or nature has become the human essence for man. It is possible to judge from this relationship the entire level of development of mankind’ (Early Writings, p. 347).

The struggle for the establishment of the normal working day was protracted and bitter. ‘As soon as the working class, stunned at first by the noise and turmoil of the new system of production, had recovered its senses to some extent, it began to offer resistance to the forcible appropriation of its entire day minus a few hours of rest’ (Capital Vol.1, p. 390). It forced the passing of five Labour Laws between 1802 and 1833, but these were successfully evaded by the bourgeoisie. However, ‘the factory workers, especially since 1838,… made the Ten Hours Bill their economic, as they had made the Charter their political, election cry’ (p. 393). This agitation let to the Act of 1844, which extended and made more enforceable the provisions of the 1833 Act. There followed an Act of 1847, which was also sabotaged by the capitalists and finally virtually annulled by a Court decision. ‘But this apparently decisive victory of capital was immediately followed by a counter-stroke. So far, the workers had offered a resistance which was passive, though inflexible and unceasing. They now protested in Lancashire and Yorkshire in threatening meetings… The factory inspectors urgently warned the government that class antagonism had reached an unheard-of degree of tension’ (p. 405). This led to the supplementary Factory Act of 1850. Subsequently, the 12-hour working day and then the 10-hour day were brought into force.

The limitation of the working day of adult workers led to a spectacular improvement in their health, and allowed them leisure time for meeting each other, talking, discussing, reading newspapers and other literature. Combined with higher wages and better living conditions, as well as with education for children, this development enabled workers to deepen and widen their knowledge far beyond their immediate experience of work-place and living-place. The cultural level thus acquired is an essential condition for the formation of the proletariat into a class transcending workplace, industry, nationality and all other determinations which, to begin with, divide the proletariat and perpetuate competition within it. This is the culture and ideology of a class everywhere pitted against the same social forces and increasingly capable of reflecting on its own struggles. To assume that the ideas of the proletariat are identical with the ruling ideas, which are those of the bourgeoisie, is to forget that the practice which constitutes the basis of those ideas is a constant struggle against bourgeois society; a struggle which may pass through different phases and take different forms, which may remain implicit for a whole epoch, but which never ceases so long as capital and wage-labour continue to exist. It is apparent, then, that the establishment of the normal working day and higher wages enable the proletariat to undertake a deeper and more comprehensive investigation of its own situation and tasks, and thus directly contributes to the creation of a communist culture within the working class.

VI

Seen within the perspective of a whole historical epoch during which the proletariat, through successive cycles of struggle and self-education, constitutes itself as a class for itself, the trade union movement takes an important place. Even though it occurs in a period of capitalist expansion and development and does not directly take up the task of shattering capitalist relations of production, it does struggle against the immanent laws of capitalist accumulation, against the tendency of capital to appropriate the maximum amount of surplus value from the proletariat, against the negation of its humanity which results from the unfettered operation of those laws; it is the means by which the proletariat asserts its humanity in this period. This is why the ‘historical and moral element’ in the determination of the value of labour-power depends less on ‘the habits and expectations with which the class of free workers has been formed’ (Capital Vol.1, p. 275), which relate to the past, than on the struggles of the proletariat, which relate to its goals, so that it is never the case that the value of labour-power is once and for all determined, fixed and unalterable; on the contrary, the struggle for an increase in the value of labour-power must continue so long as wage-labour itself continues to degrade the human value of the labourers. In the course of this struggle, the proletariat alters circumstances, revolutionises itself; it emerges from the struggle different from what it was when it entered it. Thus, to see the working class of today purely and simply as the product of capital is one-sided. That capital produces the class of wage-labourers and determines the conditions of its reproduction is true; but the class of wage-labourers as it exists today is the product of over a century of struggleagainst capital, and would not have come into existence but for that struggle.

In altering the conditions of its own reproduction, the proletariat alters the nature of capitalist production too. The improvement in wages won by the trade union movement speeds up the introduction of machinery. ‘The use of machinery for the exclusive purpose of cheapening the product is limited by the requirement that less labour must be expended in producing the machinery than is displaced by the employment of that machinery. For the capitalist, however, there is a further limit on its use. Instead of paying for the labour, he pays only the value of the labour-power employed; the limit to his using a machine is therefore fixed by the difference between the value of the machine and the value of the labour power replaced by it’ (Capital Vol.1, p. 515). Where the value of labour-power is very low, machinery may not be substituted for it even though its application leads to a reduction in the labour-time necessary for producing the commodity; ‘the field of application for machinery would therefore be entirely different in a communist society from what it is in bourgeois society’ (p. 515n.). Marx cites two such examples where the low value of labour-power impedes the introduction of machinery. ‘The Yankees have invented a stone-breaking machine. The English do not make use of it because the “wretch” who does this work gets paid for such a small portion of his labour that machinery would increase the cost of production to the capitalist. In England women are still occasionally used instead of horses for hauling barges, because the labour required to produce horses and machines is an accurately known quantity, while that required to maintain the women of the surplus population is beneath all calculation’ (pp. 516-17). Conversely, an increase in the value of labour-power accelerates the introduction of machinery: when the working hours of children were reduced without a reduction in their wages, machinery was substituted for them in the wool industry, and when the labour of women and children in the mines was forbidden, their place was taken by machinery. The development of the productive forces is thus speeded up by the trade union movement although, as always under capitalism, this occurs at the expense of the proletariat inasmuch as it increases unemployment.

Secondly, the shortening of the working day creates ‘the subjective condition for the condensation of labour, i.e. it makes it possible for the worker to set more labour-power in motion within a given time’ (p. 536). This ‘results from the self-evident law that the efficiency of labour-power is in inverse ratio to the duration of its expenditure… In manufactures like potteries, where machinery plays little or no part, the introduction of the Factory Act has strikingly shown that the mere shortening of the working day increases to a wonderful degree the regularity, uniformity, order, continuity and energy of labour’ (p. 535). If the shortening of the working day produced an intensification of labour even in industries employing little machinery, in other industries capitalists consciously and systematically used machinery as a means of squeezing out more labour. ‘This occurs in two ways: the speed of the machine is increased, and the same worker receives a greater quantity of machinery to supervise’ (p. 536). So great was the increase in intensity which followed the introduction of the Ten-Hour Act that workers were now expending more labour-power in ten hours than they had formerly expended in twelve. The speed-up inevitably led to exhaustion, disease, psychological disorders and an increase in accidents, and these in turn resulted in agitation for a further reduction of the working day to eight hours. Ultimately, then, legal regulation of the working day benefited not only the workers but also the manufacturers into whose industries it was introduced; ‘their wonderful development from 1853 to 1860, hand in hand with the physical and moral regeneration of the factory workers, was visible to the weakest eyes. The very manufacturers from whom the legal limitation and regulation of the working day had been wrung step by step in the course of a civil war lasting half a century now pointed boastfully to the contrast with the areas of exploitation which were still “free”’ (pp.408-9).

To the extent, therefore, that the upsurge of the working class combatted the production of absolute surplus-value through extension of the working day both collective and individual, and a depression of living standards, ‘capital threw itself with all its might, and in full awareness of the situation, into the production of relative surplus value, by speeding up the development of the machine system’. At the same time, it imposed ‘on the worker an increased expenditure of labour within a time which remains constant, a heightened tension of labour power, and a closer filling-up of the pores of the working day, i.e. a condensation of labour’ (p. 434). There is an acceleration of the increase in the organic composition of capital and simultaneously an acceleration of the rate at which machinery transfers its value to the product as a result of intensified use. This in turn alters the nature of surplus-value production and of the labour-force itself.

VII

Altogether, the importance of the trade unions for the working class in immense. Yet it is not entirely accurate to say that ‘the value of labour-power constitutes the conscious and explicit foundation of thetrade unions’ (p. 1069). On the surface of bourgeois society, the value of labour-power appears as the price of labour, and it is this appearance which dominates the trade-union movement. This is quite evident from its slogans – a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work, equal pay for work of equal value and so on. In other words, the aim of the movement is the achievement of what is conceived of as an equal exchange between capital and labour; it does not explicitly recognise that even a ‘fair wage’ involves the exploitation of labour-power, the appropriation of unpaid surplus labour. Consequently, the movement suffers many limitations. Since it is ‘labour’ which is sold, the concrete form taken by the labour performed becomes an important consideration, and hence trade unions start as unions of workers in a particular trade. Competition between workers of different trades remains and is in some cases intensified. With the development of industrial and general unions, ‘labour’ comes to be marketed by larger and more comprehensive agencies, yet these, too, compete with one another on the capitalist labour market. Trade unionslimit competition between the workers, but cannot entirelyeliminate it. When labourers are thrown out of work, become unemployed, and are hence no longer involved in a direct exchange with capital, they automatically cease to be within the purvey of trade unions: hence these organisations are incapable of eliminating competition between employed and unemployed workers, and indeed at times raise this competition to a principle, as in the closed shop system. Again, the appearance that labour rather than labour-power is being sold conceals the social character of the labour of proletarian housewives, so that they too fall outside the scope of trade unions, and the conditions, hours and remuneration of their labour remain without legal regulation. For these and other reasons, trade unions can never be organs of the struggle of the working class as a whole.

Even with respect to the workers whom it directly represents, the trade union suffers from deficiencies. In the first place, although the fight to establish them involves a challenge to bourgeois legality, once established, they derive their strength from the fact that they are the agencies recognised in law as representatives of the interests of the proletariat. Retaining this advantage necessitates remaining within the framework of the law, and hence knowledge of the law and legal procedures. This is necessarily a function of specialists. Thus, the trade union leaderships inevitably become separated from the mass of the workers as a bureaucracy, so that the workers can no longer directly represent their interests through them. Intensification of labour is another example. From the standpoint of trade unionism, an increase in wages is adequate compensation for the increased labour that is extracted with intensification; the detrimental effects on labour-power – through fatigue, mental strain, accidents, etc. – are not sufficiently taken into consideration. This is why the intensification of labour which takes place in a period of capitalist expansion is compatible with trade unions and requires only the victimisation of class-conscious militants, whereas the wage-cuts and extension of the working day which the bourgeoisie have to carry out in a crisis demand the smashing of trade unions as occurred under fascism. (The fascist syndicates are in no sense trade unions – see F. Neumann, European Trade Unionism and Politics, extract reproduced inBCP 2.) This instance illustrates very clearly both the importance of trade unions for the working class and their deficiencies. For the drastic increase in the exploitation of labour-power which occurs under fascism demonstrates that it is not merely in the early stages of capitalism that the bourgeoisie opposes the existence of combinations of workers and strives in this way to increase the production of absolute surplus-value. Hence the importance for the proletariat of defending trade unions so long as wage-labour itself lasts. And yet, inasmuch as they are unable to unite the proletariat, the trade unions prove themselves unable to defend themselves against a determined attack; such a defence, like their original formation, requires the capacity and willingness to wage a ‘civil war’.

Ultimately, the limitation of trade unionism is that its basis is wage-labour: to undertake the regulation of the value of labour-power presupposes that labour-power is a commodity, presupposes the capital-wage-labour relation. As the working-class struggle enters a phase where it is pitted against capital itself, therefore, the trade unions become inadequate as instruments of struggle and the proletariat has to discover alternative forms of organisation through which it expresses its interests. However, prior to an examination of this transition, it is necessary first to understand the role played by the other major means through which the proletariat struggles for its interests under capitalism – the working-class parliamentary party.

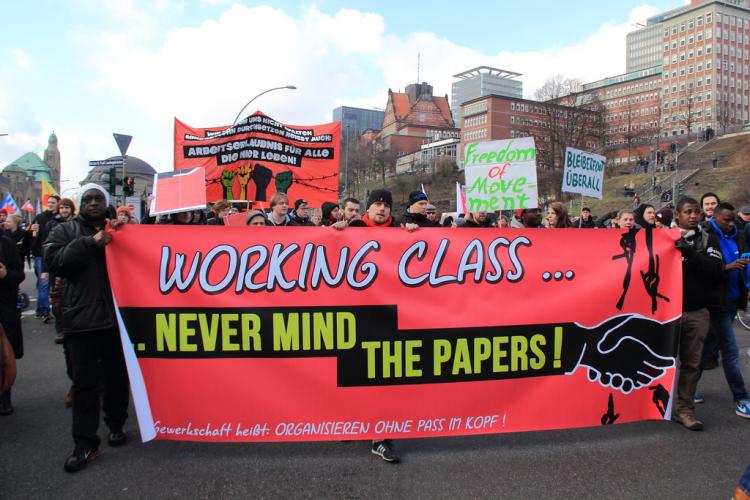

“European trade union demonstration” byJoost (formerly habeebee) is licensed underCC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- 1. See https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/blog/emergence-working-class-learning-process