Towards a History of the Trotskyist Tendencies after Trotsky

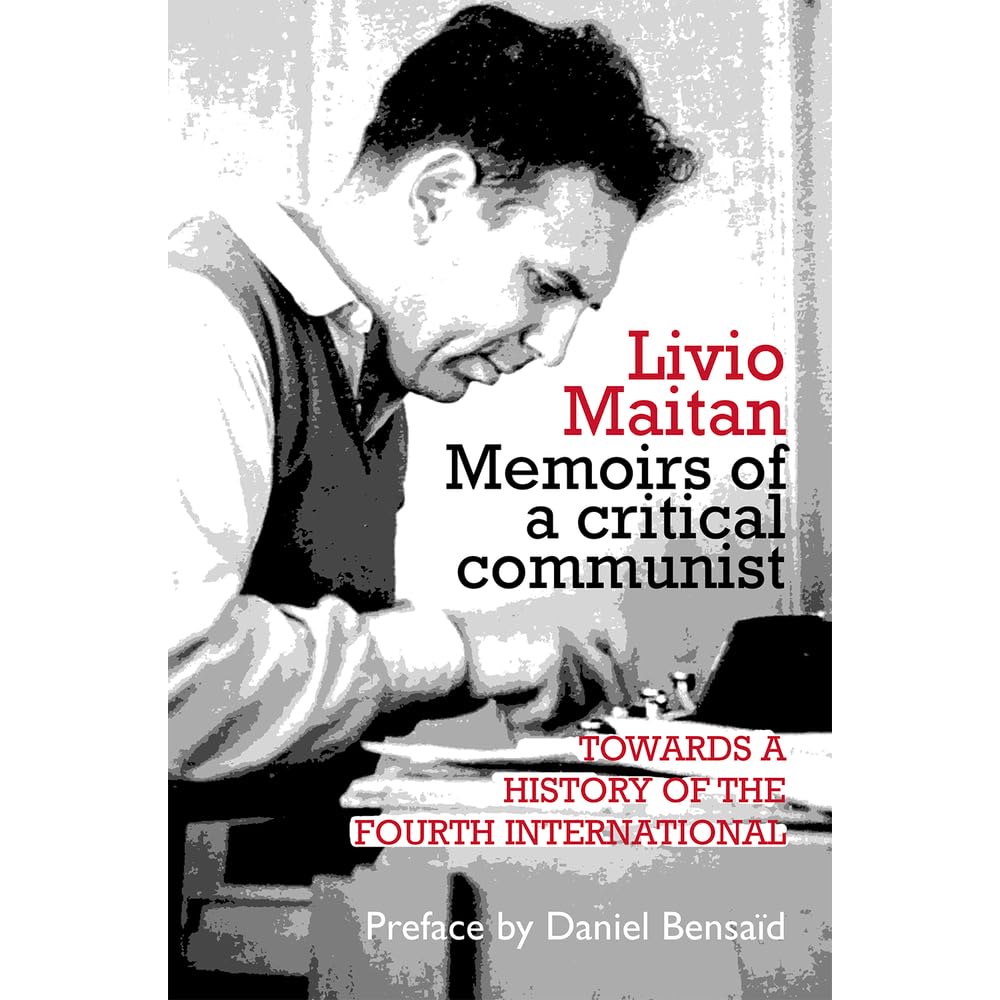

A Review of Memoirs of a Critical Communist: Towards a History of the Fourth International by Livio Maitan

Daniel Gaido

National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), Argentina

danielgaid@gmail.com

Abstract

This work, based on the premise that ‘Trotskyism’ in Trotsky’s lifetime was nothing but the name given to Marxism in its fight against the Stalinist bureaucracy, offers an overview of the history of Trotskyist tendencies after Trotsky’s assassination which highlights the need not only of addressing programmatic and strategic issues (above all, the long-standing and growing accommodation to bourgeois democracy of most of the Trotskyist tendencies) but also of taking an in-depth look at a series of organisational practices that the Trotskyist tendencies have inherited from Zinovievism and Stalinism and that have greatly contributed to their current weakness.

Keywords

Trotskyism – socialism – workers’ party – sectarianism – parliamentarism

Livio Maitan, (2020) Livio Maitan: Memoirs of a Critical Communist: Towards a History of the Fourth International, translated by Gregor Benton, London: The Merlin Press.

Introduction

The history of the Trotskyist tendencies after Trotsky still is, more than 80 years after Trotsky’s death, largely terra incognita, or rather a bazaar in which all kinds of sects peddle their myths. Only from time to time does a work emerge that takes the history of Trotskyism out of the realm of mythology and provide us with the elements we need to reconstruct the actual experience of the Trotskyist militants in a particular time and place, such as Sam Bornstein and Al Richardson’s two volumes on the history of British Trotskyism from 1924 to 1949,

This is regrettable because ‘Trotskyism’ in Trotsky's lifetime was nothing but the name given to Marxism in its struggle against the Stalinist bureaucracy: the Transitional Programme adopted by the Fourth International in 1938 was merely the development of the programmatic debates that took place in the Communist International (particularly in its third and fourth congresses), which were interrupted by the rise of Stalinism.

The works available so far fall into two main categories: monographs such as those mentioned above, restricted to a country and often to a specific Trotskyist tendency for a limited period of time, or general reviews written from the point of view of one of those tendencies, generally of an apologetic character, even if such apology is not without self-criticism (for example, the books of Frank and Moreau, written from the point of view of the ‘United Secretariat of the Fourth International’).

Maitan’s book tells the Historia Calamitatum of the Fourth International from the point of view of its official leadership (to which Maitan belonged) until the split in 1953, then from the point of view of the International Secretariat led by Michel Pablo and, from its creation in 1963, from the point of view of the United Secretariat of the Fourth International until the death of the author. Given that the United Secretariat was, for better or worse, the dominant Trotskyist current for most of the period under consideration, and that it continues to exist to this day, a critical reading of Maitan’s book is a good introduction to the subject of the history of Trotskyist tendencies after Trotsky.

The Second World War and the Democratic Counterrevolution in Western Europe

The first chapter of Maitan’s book deals cursorily with the ‘Dramatic battles of the 1930s and the early 1940s’, without explaining why the European Trotskyist organisations emerged very weakened, both numerically and programmatically, from the Second World War. In the paradigmatic case of France, this was due to the policy of sectarian abstentionism in the face of resistance to the Nazi occupation adopted by the French Trotskyists after the arrest of their main leader, Marcel Hic, by the Gestapo in October 1943. This policy, which continued during the liberation process, was carried out with the support of the European Secretariat of the Fourth International led by Michel Pablo. The Stalinist parties, on the contrary, were transformed into mass organisations of the working class in countries like France and Italy primarily because of their role in the resistance, even though that participation had a chauvinist, popular-frontist and pro-imperialist character. Their sectarian policy turned the postwar Trotskyist organisations into groups of at most a few hundred people confronting Stalinist parties often comprising hundreds of thousands of workers, as in France and Italy.

A concomitant factor that turned the Trotskyist organisations in Europe, and particularly the French section, into sects in the immediate postwar period, while the Stalinist organisations became mass working-class parties, was their inability to foresee the coming of a democratic counterrevolution under the aegis of American imperialism. The outbreak of the Second World War found US Trotskyism divided into two organisations: the Socialist Workers Party led by James Cannon, and the Workers Party led by Max Shachtman. The downfall of Mussolini on 24 July 1943 resulted in the appearance of a third current: a minority within the SWP led by Felix Morrow, Jean van Heijenoort and Albert Goldman. Confronting the SWP leaders’ line, according to which US imperialism would operate in Europe through ‘Franco-type governments’, the minority argued that imperialism would use democratic regimes to stem the advance of the revolution, propping them up with economic aid, and that it would be helped in this task by the Socialist and Communist Parties, which would revive the policy of class collaboration known as the Popular Front. The task of the European Trotskyists was therefore to wrest control of the masses from those parties through democratic and transitional demands (a democratic republic, a constituent assembly, etc.) that would help the workers discover the anti-socialist agenda of their mass organisations through their own experience. The Morrow–Goldman–Heijenoort tendency's inglorious ending precluded any serious analysis of the consequences of the policies pursued by the SWP leadership, which were extended to Europe by the European Secretariat of the Fourth International now led by Michel Pablo.

Morrow’s swan song in the SWP was the ‘International Report’ submitted on behalf of the minority to the June 1946 plenary, which asserted:

What hair-raising nonsense the majority has defended in the name of the unchanging program! In the name of the unchanging program, Comrade Cannon, you taught the following things: That our proletarian military policy means that we should telescope together overthrow of capitalism and defence of the country against foreign fascism. That the Polish revolutionists should subordinate themselves to the Russian Army. That there is an objectively revolutionary logic brought about by the Russian victories. That naked military dictatorships are the only possible governments in Europe because it is impossible to set up a new series of Weimar republics in Europe. That American imperialism is at least as predatory as Nazi imperialism in its methods in Europe. That it is theoretically impossible for America to help rebuild or feed Europe. That there are no democratic illusions in Europe. That there are no illusions about American imperialism. That amid the revolutionary upsurge it is reformist to call for the republic in Greece, Italy and Belgium or the Constituent Assembly. That to speak of a Stalinist danger to the European revolution is only possible for a professional defeatist. That the fate of the Soviet Union would be decided by the war but only careless people think the war is over.

Morrow 1946, pp. 28–9.

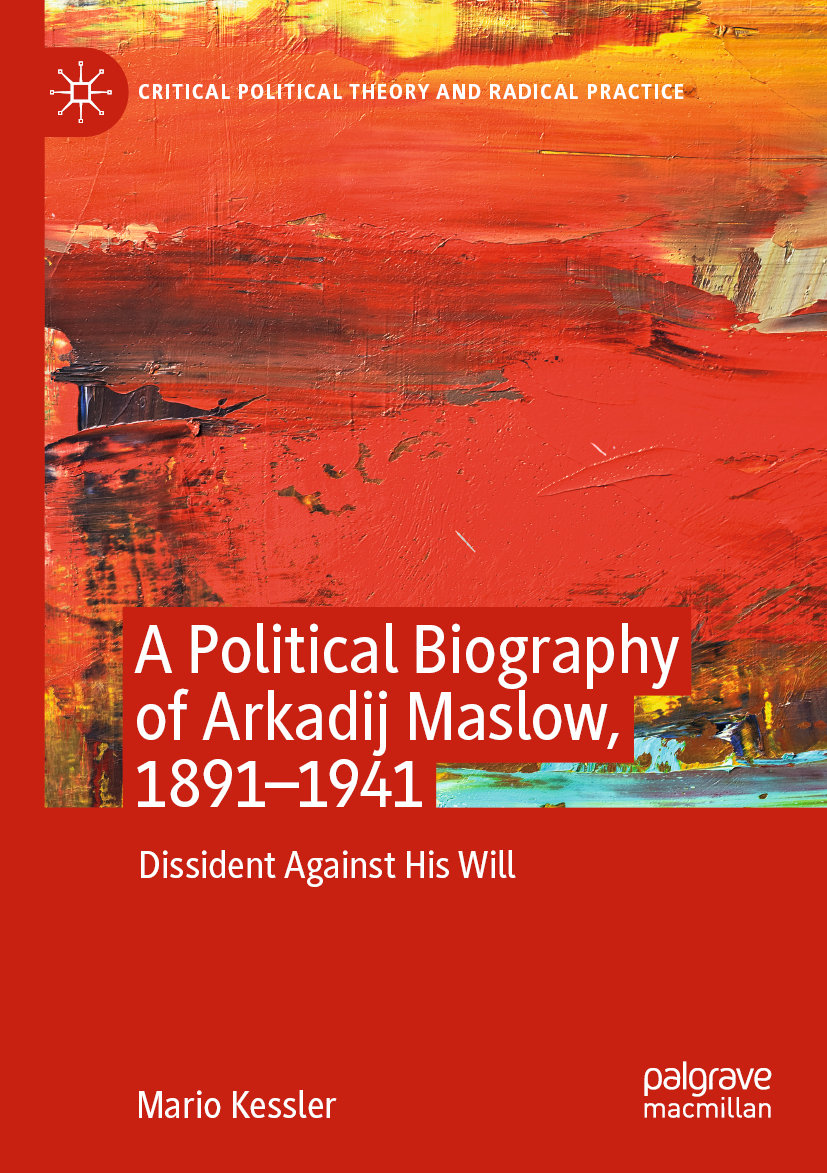

A Review of A Political Biography of Arkadij Maslow, 1891–1941: Dissident Against His Will by Mario Kessler

Daniel Gaido

National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), Argentina

Mario Kessler, (2020) A Political Biography of Arkadij Maslow, 1891–1941: Dissident Against His Will, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

This scholarly and well-written biography can be read both as an independent book and as a companion volume to Mario Kessler’s massive biography of Maslow’s life-long companion, Ruth Fischer: Ein Leben mit und gegen Kommunisten (1895–1961).

Both Arkadij Maslow and Ruth Fischer belonged to a generation that awoke to political life amid the butchery of the First World War, the collapse of the Second International and its national sections (first and foremost, the Social Democratic Party of Germany, SPD) and the way out of the relapse into barbarism offered by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. In other words, none of them had roots in the traditions of the Second International such as Rosa Luxemburg, Paul Levi, or Lenin and Trotsky did, and therefore they were unable to grasp what Lenin meant when he wrote that Karl Kautsky (its main theoretician) was a renegade: namely that he, and the party and union bureaucracy, whose spokesman he had become, hadbetrayed the legacy of the Second International and the SPD. Maslow and Fischer’s political project, along with the rest of the ultra-left wing, was thus one of throwing the baby out with the bathwater: unable to separate the Marxist wheat from the parliamentarist chaff, they embarked on a one-sided crusade against Social Democracy which helped pave the way for the rise of Stalinism as well as for their own elimination by Stalin and his minion Ernst Thälmann.

Arkadij Maslow was the party name of Isaak Yefimovich Chemerinsky. Born in 1891 in Yelisavetgrad, Ukraine (then part of the Russian empire), in 1889 he moved with his family to Germany, where the gifted Isaak studied music. As a young man, he performed in piano concerts throughout Europe, Japan, and Latin America. At age twenty-three, however, he abandoned his career as a musician and enrolled in mathematics and physics at the University of Berlin in 1914, where he studied with exceptional figures like Max Planck and Albert Einstein. But war and revolution radicalised Chemerinsky, shifting his interest from art and music to politics. He began working illegally for the SPD in 1916, and he established contacts with the Spartacus League, especially with August Thalheimer, at the beginning of 1918. He joined the Spartakusbund on 5 December 1918, in order to agitate among Russian prisoners of war, and also worked as a translator for the newly established KPD, of which he was a founding member, where he adopted the party name Arkadij Maslow. He cooperated closely with Max Levien, one of the leaders of the Bavarian Soviet Republic that emerged in the wake of the German November Revolution of 1918, and stayed a close friend until Levien was executed in the Soviet Union on Stalin’s orders in 1937, in the framework of the Great Purge.

In 1919, Maslow met his life partner, the young Austrian Elfriede Friedländer, who became known under her party name Ruth Fischer. The couple never married, but their relationship lasted until Maslow’s death in 1941. If Fischer was the best-known public figure, Maslow was the polyglot intellectual of the couple. During the critical years of their political activity, public attention focused on Fischer, not least because, from May 1924 to July 1926, Maslow was imprisoned by the German state on fabricated charges.

Kessler’s book recounts many fascinating anecdotes, some not directly related to Maslow’s life. For instance, we learn ‘that the SPD daily Vorwärts printed a hate “poem” by Arthur Zickler on January 13, 1919 that called for the murder of Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Karl Radek’, and that ‘In 1933 Zickler joined the Nazi Party’ (p. 16, n. 27). Since the entire run of theVorwärts from 1891 to 1933 has been digitised by theBibliothek der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, the ‘poem’ in question can be read online; it was entitledDas Leichenhaus: ‘The Morgue’.

Describing the German revolution that broke out in November 1918, from the Spartacist Uprising and the subsequent murder of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in January 1919, to the Kapp Putsch in March 1920, Kessler recalls that ‘The counter-revolution was forced to assume a democratic form until the putsch’ (p. 23).

Maslow and Fischer were united in their opposition to Rosa Luxemburg’s political heir Paul Levi, particularly to the united-front policy that Levi outlined in his ‘Open Letter’ of 8 January 1921, and they joined hands with Zinoviev’s envoy Mátyás Rákosi to depose Levi as leader of the KPD in February 1921. Maslow even called Levi the ‘German Serrati’ (p. 28). Kessler points out that ‘Levi’s fall strengthened the ultra-leftists, among them Fischer and Maslow’ (p. 35).

This paved the way for the disastrous putsch known as the ‘March Action’ of 1921. Kessler points out that the unification of the KPD with the left wing of the USPD, engineered by Levi, had resulted in a significant gain for the Berlin district organisation: ‘membership rose to 45,000 by the end of 1920, only to fall back to roughly 2,300 after the fiasco of the March Action’ (pp. 36–7). KPD membership as a whole shrank from 359,000 in December 1920 to around 157,000 in August 1921 (p. 40, n. 40).

Since the ultra-left gathered around Fischer and Maslow rejected the united front – i.e., it ‘opposed the idea of joint action with other forces of the labor movement’ (p. 46) – they also rejected the slogan of a ‘workers’ government’ with the Social Democrats raised in 1922 by the KPD under the leadership of Ernst Meyer. The same polemics continued when Heinrich Brandler was elected new party chair and his supporters August Thalheimer and Walter Stoecker became members of the new KPD Zentrale at the beginning of 1923. Brandler was the main proponent of the Guidelines on the Tactics of the United Front and of the Workers’ Government (Leitsätze zur Taktik der Einheitsfront und der Arbeiterregierung) adopted at the third KPD congress convened in Leipzig from 28 January until 1 February 1923, also rejected by Fischer and Maslow.

In ‘A Letter to the German Communists’ dated 14 August 1921, Lenin wrote that ‘Maslow, who is playing at Leftism and wishes to exercise himself “hunting Centrists”’ had ‘more zeal than sense’.

After the Ruhr crisis and the fiasco of the ‘German October’ in 1923, which was the last chapter in the German revolution that had begun in November 1918, a bitter controversy ensued within the KPD between ‘the “rightist” party leadership around Brandler and Thalheimer on the one hand, and Fischer, Maslow, Arthur Rosenberg and Werner Scholem, as well as Ernst Thälmann, the Hamburg party leader of the left opposition, on the other’ (p. 83). For Zinoviev, as Chairman of the Communist International, ‘The easiest way to escape responsibility for the failed policy was to blame Brandler, Thalheimer as well as Radek’ (p. 82). As a result, the ultra-left in the KPD once again received considerable support from Zinoviev and the Comintern apparatus. As early as January 1924, Zinoviev denounced ‘the leaders of German Social Democracy’ as ‘fascists through and through’ and concluded that only the ‘slogan “unity from below”’ – which excluded the leaders of the SPD – ‘must become a living reality’ (p. 85).

At Zinoviev’s initiative, control of the KPD passed into the hands of Fischer, Maslow and their followers (which included the jurist Karl Korsch) in April 1924. Zinoviev’s backing of the KPD ultra-lefts made all the more sense since they were ardent supporters of the new policy of ‘Bolshevisation’. As a letter from Zinoviev to the KPD Zentrale of 26 February 1924 attests, the term ‘Bolshevisation’ was ‘most likely coined at a session of the KPD leadership on 19 February 1924. In the letter he considered the term to be a “wonderful expression”’ (p. 85).

The policy of ‘Bolshevisation’ was officially adopted by the Fifth Congress of the Communist International, held in Moscow during June and July 1924. There, Zinoviev described it as follows: ‘Bolshevisation is the creation of a firmly established, centralised organisation as if carved out of a stone that harmoniously and fraternally dispenses with the differences in their ranks, as Lenin has taught’.

that the promotion or expulsion of party functionaries was no longer determined by internal factors but instead by the demands of Soviet party leaders. It soon became obvious that the term also implied that any criticism of Soviet policy could be denounced as anti-Bolshevist deviation and therefore as essentially anti-communist. The result was a dramatic curtailment of freedom of discussion inside every party. (p. 94.)

For the Independence of Soviet Ukraine

Zbigniew Marcin Kowalewski

Abstract: Written in 1989, this article tells the true but unknown and dramatic story of Bolsheviks faced during the civil war with an unexpected national revolution of the oppressed Ukrainian people, the conflict-ridden relationships between Russian and Ukrainian communists and the great dilemma of what should be Ukraine: a part of the Soviet but, as in the imperial past, “one and indivisible” Russia or an independent Soviet state?1

Despite the giant step forward taken by the October Revolution in the domain of national relations, the isolated proletarian revolution in a backward country proved incapable of solving the national question, especially the Ukrainian question which is, in its very essence, international in character. The Thermidorian reaction, crowned by Bonapartist bureaucracy, has thrown the toiling masses far back in the national sphere as well. The great masses of the Ukrainian people are dissatisfied with their national fate and wish to change it drastically. It is this fact that the revolutionary politician must, in contrast to the bureaucrat and the sectarian, take as his point of departure. If our critic were capable of thinking politically, he would have surmised without much difficulty the arguments of the Stalinists against the slogan of an independent Ukraine: “It negates the position of the defence of the Soviet Union”; “disrupts the unity of the revolutionary masses”; “serves not the interests of revolution but those of imperialism”. In other words, the Stalinists would repeat all the three arguments of our author. They will unfailingly, do so on the morrow. (...) The sectarian as so often happens, finds himself siding with the police, covering up the status quo, that is, police violence, by sterile speculation on the superiority of the socialist unification of nations as against their remaining divided. Assuredly, the separation of Ukraine is a liability as compared with a voluntary and equalitarian socialist federation: but it will be an unquestionable asset as compared with the bureaucratic strangulation of the Ukrainian people. in order to draw together more closely and honestly, it is sometimes necessary first to separate.2

The quoted article by Trotsky, “The Independence of Ukraine and Sectarian Muddleheads” (July 1939), is, in a number of ways, much more important than the article of April the same year, “The Ukrainian Question”. First of all, it unmasks and disarms the pseudo-Marxist sectarians who, in the name of defending proletarian internationalism transform it into a sterile abstraction, and reject the slogan of national independence of a people oppressed by the Kremlin bureaucracy. In this article, Trotsky places himself in the continuity of the ideological struggle waged by Lenin against the “tendency to imperialist economism”, a tendency which was active in the ranks of Bolshevik Party as well as in the far left of international social democracy. It should be clear that the adjective “imperialist” that Lenin attributes to this form of economism in the revolutionary movement in relation to the national question, is justified by the theoretical reasons evoked by the author of the term. A sociological examination would show that this tendency is mainly based among revolutionary socialists belonging to the dominant and imperialist nations. The sectarians denounced by Trotsky, are only a new version of the same tendency that Lenin fought against at the time of the discussion on the right of nations to self-determination in the context of an anti-capitalist revolution.

Second, Trotsky’s article contains theoretical and political considerations which are indispensable for understanding the correctness and the need for a slogan such as that of independence for the Soviet Ukraine as well as for a national revolution of an oppressed people as a factor and component of the anti-bureaucratic revolution in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. To fully appreciate the richness of this contribution, readers are invited to study the article themselves.

Third, Trotsky explains that in a case like that of Ukraine, real internationalism and a real search for the international unity of the working class are impossible without clear and resolute support for national “separatism”.

To make possible a genuine brotherhood of the peoples in the future, the advanced workers of Great Russia must even now understand the causes of Ukrainian separatism as well as the latent power and historical lawfulness behind it, and they must without any reservation declare to the Ukrainian people that they are ready to support with all their might the slogan of an independent Soviet Ukraine in a joint struggle against the autocratic bureaucracy and against imperialism.3

It goes without saying that this task is the responsibility of the vanguard of the international workers’ movement even before being that of the Russian proletariat. The defence of the slogan of Ukrainian independence adopted by the World Congresses of the Fourth International in 1957 and 1979, is a task of enormous political importance today. The rise of national mass movements of the oppressed peoples of the USSR demands that. the slogan of national independence should be a part of our general propaganda and agitation. If this is not done, the socialist opposition in the USSR will leave the field open to the bureaucracy, which hopes to isolate the anti-bureaucratic struggles waged in the non-Russian republics from the fight of the workers in Great Russia. They thus omit one of the basic transitional tasks of the anti-bureaucratic struggle.

Fourthly, Trotsky contributes an essential clarification to the historical discussion on the right of nations to self-determination while eliminating from this Leninist slogan its abstract and politically redundant features. Trotsky explains that, if the oppression of a people is an objective fact, we do not need this people to be in struggle and to demand independence in order to advance the slogan of independence. At the time when Trotsky raised this slogan, nobody in the Soviet Ukraine could demand such a thing without having to face execution or becoming a prisoner in the Gulag. A wait-and-see policy would only lead to the political and programmatic disarming of revolutionaries. An oppressed people needs independence because it is oppressed. Independence, states Trotsky, is the indispensable democratic framework in which an oppressed people becomes free to determine itself. In other words, there is no self-determination outside the context of national independence. In order to freely determine her relations with other Soviet republics, in order to possess the right to say yes or no, Ukraine must return to herself complete freedom of action, at least for the duration of this constituent period. There is no other name for this than state independence. “In order to exercise self-determination – and every oppressed people needs and must have the greatest freedom of action in this field – there has to be a constituent congress of the nation. But a ‘constituent’ congress signifies nothing else but the congress of an independent state which prepares anew to determine its own domestic regime as well as its international position.”4

Faced with the implacable rigour of this explanation, any other discourse on the right of oppressed nations to self-determination can only be sustained by sleight-of-hand. This right cannot be defended without fighting for the oppressed people to have the means of exercising it; that is to say without demanding the state independence necessary for the convocation of a free constituent assembly or congress.

Finally, and this is a question of signal importance, Trotsky recognised that the October revolution did not resolve the national question inherited from the Russian empire. Isolated in a backward country, it could only bring it to resolution with great difficulty. But was it equipped for that? In the perspective of a new, anti-bureaucratic, revolution, we have to decide whether the same means can be reused or if a totally new approach is necessary. I think that Trotsky was convinced that the second option was correct. This is a question of the first importance that seems never to have been taken up by the Trotskyist movement, although it is a necessary starting point for any discussion on the relevance of Trotsky’s slogan of 1939.

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic – formally (and fictively like Byelorussia) a member of the United Nations – is the most important of the non-Russian republics of the Soviet Union. It is also the biggest country in Europe after Russia in surface (603,700 square kilometres), and one of the biggest in population (more than 50 million, 74% of whom are Ukrainian). The Ukrainian people form the largest oppressed nation in the USSR and Europe. The urban working class constitutes more than 50% of the total population and more than 75% of the Ukrainian population of the republic. The liberation of the enormous potential that this class represents from the dual burden of bureaucratic dictatorship and national oppression is a fundamental task and a condition for the development of the anti-bureaucratic revolution in the USSR and Eastern Europe, as well as for the social revolution on the entire continent. It is impossible to imagine any advance in building socialism in the USSR and in Europe without the victory of the Ukrainian national revolution which has, as Trotsky explained, an international strategic dimension. What the sectarians ignore in taking up this question is the fact that the national revolution, one of the most important and most complex forms of the class struggle, cannot be avoided by simple references to the anti-bureaucratic revolution in the USSR as a whole or the future European and world revolution.5

Bolshevism faced with an unexpected national revolution

Considered by many people – including Marx and Engels at one time –as a “people without history”,6 the Ukrainian people constituted itself as a nation in a “historical” manner par excellence, that is heroically. In 1648, the community of freemen and of military democracy, known as the Cossacks, formed a people’s liberation army, and launched a huge peasant uprising against the Polish state, its ruling class and its church. The nation state established during this rising did not manage to stabilise but the Cossack and peasant revolution crystallised a historical nation even before the shaping of the modem nations through the expansion of capitalism.7 Since the end of the 18th century, the bulk of Ukrainian territory had been transformed into a province of the Tsarist empire, known as “Little Russia”. On the eve of the Russian revolution, it was a “European”-type colony.8 Compared to the general level of socio-economic development in this empire this region was one of the most industrialised and characterised by a strong penetration of capitalism in agriculture. Ukrainian was synonymous with peasant because around 90% of the population lived in the countryside. Among the 3.6 million proletarians (12% of the population), 0.9 million worked in industry and 1.2 million in agriculture. As a product of a very uneven development of capitalism, half of the industrial proletariat was concentrated in the mining and steel enclave of the Donbas. Because of the colonial development and the Tsarist “solution” to the Jewish question, only 43% of the proletariat was of Ukrainian nationality, the rest being Russian, Russified and Jewish. The Ukrainians constituted less than a third of the urban population.9 The western part of Ukraine, Galicia, belonged to the Austro-Hungarian empire. The two central demands of the renascent national movement were the independence and unity (samostiinist´ i sobornist´) of Ukraine.

The 1917 revolution opened the road to the Ukrainian national revolution. It was the most powerful, the most massive and the most violent of the all the revolutions of the oppressed nations of the empire. The masses demanded a radical agrarian reform, independence, the constitution of a Ukrainian government and independence. The opportunist petty bourgeois and workers’ parties of the Central Rada (council) which led the national movement opposed the demand for independence. They only proclaimed it after the October revolution to which they were hostile. By authorising the passage of counter-revolutionary military units, the Central Rada provoked a declaration of war by Soviet Russia against the Ukrainian People’s Republic. The Bolsheviks were very badly prepared to deal with the Ukrainian national revolution.

The right to national self-determination put forward by Lenin was a slogan that had not been very well assimilated by the party. It was even challenged by a sizeable current, characterised by Lenin as “imperialist economism”. This challenge was particularly dangerous as it appeared within a proletarian party of a nation that was traditionally an oppressor and had become imperialist, in an empire characterised by Lenin as an enormous prison of peoples. Apart from Lenin’s writings, the only overall work on the national question at the disposal of the Bolshevik Party was the confused, indeed largely wrong study by Stalin. Written in 1913, it did not even take up the national question in the framework of imperialism.10 Lenin himself expressed confused and ill-thought out positions such as the excessive inspiration that he drew from the example of the American melting-pot and a categorical rejection of a federalist solution. He condemned this as contradicting his idea of a centralised state and demanded that each nationality choose between complete separation and national-territorial autonomy within a centralized multi-national state. He educated the party in this spirit for more than ten years. After the revolution, and without giving any explanation for his turnaround, he proclaimed the federation of nations as the correct solution and compatible with state centralism – a shift that many Bolshevik leaders did not take seriously. Over and above the democratic slogan of the right to self-determination, Bolshevism had neither a programme nor a strategy of national and social permanent revolution for the oppressed peoples of the empire.

In Ukraine, apart from a few exceptions, the Bolshevik Party (like the Menshevik Party) was only active within the most concentrated and modern section of the proletariat, which was not of Ukrainian nationality. The spread of communism within the proletariat followed the dynamic of the development of a colonial industrial capitalism. Political action within the national proletariat was the domain of Ukrainian social democracy which placed itself outside the Bolshevik/Menshevik split and was accused by the former of capitulating to Ukrainian “bourgeois nationalism”. The “national” bourgeoisie hardly existed. At this period, the distinction between the nationalism of the oppressors and that of the oppressed was already present in Lenin’s writings but both were considered bourgeois. The notion of revolutionary nationalism had not yet appeared. Social Revolutionary populism, which was becoming national and autonomous from its Russian equivalent represented another active political force within the Ukrainian masses. The Bolshevik Party in Ukraine used only Russian in its press and propaganda. It ignored the national question and did not even have a leadership centre in the territory. It is not surprising that when the national revolution broke out it was caught unarmed.

In Ukraine, the Bolshevik Party only tried to organise as a separate entity after the Brest-Litovsk treaty, that is during the first Bolshevik retreat and at the beginning of the occupation of the country by the imperialist German army. At the ad hoc conference in Taganrog in April 1918, there were several tendencies present. On the right, the “Katerynoslavians” with Emmanuiil Kviring. On the left, the “Kievans” with Yury Pyatakov, but also the “Poltavans” or “nationals” with Mykola Skrypnyk and Vasyl Shakhrai, strengthened by the support of a group from the extreme left of Ukrainian social democracy. The right, basing itself on the Russian industrial proletariat proposed to form the Russian CP(B) in Ukraine. The “Poltavans” and the “Kievans” wanted an entirely independent Bolshevik party. A section of the “Poltavans” wanted to settle the national question in a radical way through the foundation of an independent Soviet Ukraine. Shakhrai, the most radical, even wanted the party to be called the Ukrainian CP(b). The “Kievans” were for an independent party (and perhaps a state) while denying the existence of the national question and considering the right to national self-determination an opportunist slogan. With Pyatakov they represented the most extreme proponents of “imperialist economism”. However, at the same time, they identified with Bukharinist “left communism” and were hostile to the Brest-Litovsk peace and to Leninist centralism. In order to assert themselves in opposition to Lenin they needed an independent Bolshevik party in Ukraine. Moreover, they considered that a particular strategy was necessary in Ukraine directed towards the peasant masses and based in their insurrectional potential. It was for this reason that the “Kievans” allied with the “Poltavans”. And it was Skrypnyk’s position that won out. Rejecting Kviring’s approach on the one hand and Shakhrai’s on the other, the conference procaimed the Communist Party(b) in Ukraine as the Ukrainian section, independent of the Russian CP(b), of the Communist International.11

Skrypnyk, a personal friend of Lenin, and a realist always studying the relationship of forces, was seeking a minimum of Ukrainian federation with Russia and a maximum of national independence. In his opinion, it was the international extension of the revolution which would make it possible to resist in the most effective fashion the centralising Greater Russian pressure. At the head of the first Bolshevik government in Ukraine he had had some very bitter experiences: the chauvinist behaviour of Muraviev, the commander of the Red Army who took Kiev, the refusal to recognize his government and the sabotage of his work by another commander, Antonov-Ovseyenko, for whom the existence of such a government was the product of fantasies about a Ukrainian nationality. In addition, Skrypnyk was obliged to fight bitterly for Ukrainian unity against the Russian Bolsheviks who, in several regions, proclaimed Soviet republics, fragmenting the country. The integration of Galicia into Ukraine did not interest them either. The national aspiration to sobornist´, the unity of the country, was thus openly flouted. It was with the “Katerynoslavian” right wing of the party that there was the most serious confrontation.12 It formed a Soviet republic in the mining and industrial region of Donetsk-Kryvyi Rih, including the Donbas, with the aim of incorporating it into Russia. This republic, its leaders proclaimed, was that of a Russian proletariat “which does not want to hear anything about some so-called Ukraine and has nothing in common with if.”13 This attempted secession could count on some support in Moscow. The Skrypnyk government had to fight against these tendencies of its Russian comrades, for the sobornist´ of the Soviet Ukraine within the national borders set, through the Central Rada, by the national movement of the masses.

The first congress of the CP(B) of Ukraine took place in Moscow. For Lenin and the leadership of the Russian CP(B) the decision of Taganrog had the flavour of a nationalist deviation. They were not ready to accept an independent Bolshevik party in Ukraine or a Ukrainian section of the Komintern. The CP(B) of Ukraine could only be a regional organisation of the pan-Russian CP(B), according to the thesis “one country, one party”. Is Ukraine not a country?

Skrypnyk, considered responsible for the deviation, was eliminated from the party leadership. In this situation, Shakhrai, the most intransigent of the “Poltavans” went over to open dissidence. In two books of inflammatory content, written with his Ukrainian Jewish comrade Serhii Mazlakh, they laid the foundations of a pro-independence Ukrainian communism. For them, the Ukrainian national revolution was an act of enormous importance for the world revolution. The natural and legitimate tendency of this revolution and its growing over into a social revolution could only lead to the formation of a workers’ and peasants’ Soviet Ukraine as an independent state. The slogan of independence was thus crucial to ensure this growing over, for forming the workers’-peasants’ alliance, to make it possible for the revolutionary proletariat to take power and to establish a real and sincere unity with the Russian proletariat. It was only in this way that Ukraine could become a stronghold of the international proletarian revolution. The contrary policy would lead to disaster. This was the message of the Shakhrai current.14

And it was indeed a disaster.

The reasons for the failure of the second Bolshevik government

In November 1918, under the impact of the collapse of the central powers in the imperialist war and the outbreak of revolution in Germany, a generalised national insurrection overthrew the Hetmanate, a fake state established in Ukraine by German imperialism. The opportunist leaders of the former Central Rada of the Ukrainian People’s Republic who, a short while before, had made a compromise with German imperialism, took the head of the insurrection to restore the Republic and its government, this time called the Directory. Symon Petliura, a former social democrat who had become a rightwinger swearing ferocious hatred of Bolshevism, became the de facto military dictator. But this unprecedented rise of a national revolution of the masses was also the rise of a social revolution. Just as they had previously done faced with the Central Rada, the masses rapidly lost their illusions in Petliura’s Directory, and turned again to the social programme of the Bolsheviks. The far left of the Ukrainian Social Revolutionary Party, called the Borotbists, which was increasingly pro-Communist, affirmed its ideological influence among the masses.15

In a situation favourable to the possibility of a convergence between the Russian revolution and the Ukrainian revolution, the Red Army again entered the country, chased out the Directory, and established the second Bolshevik government. Pyatakov was at the head of this government before being rapidly recalled to Moscow.

Although continuing to ignore the national question – for him the Ukrainian revolution was not a national but a peasant revolution – the Pyatakov government, sensitive to the social reality of Ukraine, wanted to be an independent state power. It considered such power indispensable in order to ensure the growing over of the peasant revolution into the proletarian revolution and to give proletarian leadership to the people’s revolutionary war. Moscow appointed Christian Rakovsky to take Pyatakov’s place. Recently arrived from the Balkans, where the national question was particularly complicated and acute, he declared himself a specialist on the Ukrainian question and was recognised as such in Moscow, including by Lenin. In reality, although he was a very talented militant and completely devoted to the cause of the world revolution, he was completely ignorant and dangerous in his so-called speciality. In Izvestia, the Soviet government newspaper, he announced the following theses: the ethnic differences between Ukrainians and Russians are insignificant, the Ukrainian peasants do not have a national consciousness, they even send petitions to the Bolsheviks to demand to be Russian subjects; they refuse to read revolutionary proclamations in Ukrainian while devouring the same thing in Russian. The national consciousness of the masses has been submerged by their social class consciousness. The word “Ukrainian” is practically an insult for them. The working class is purely of Russian origin. The industrial bourgeoisie and the majority of the big landowners are Russian, Polish or Jewish. In conclusion Rakovsky did not even recognize a national entity in Ukraine and for him the Ukrainian national movement was simply the invention of the intelligentsia that supported Petliura, who were using it in order to hoist themselves into power.16 Rakovsky understood perfectly that the Bolshevik revolution in Ukraine was the “strategic knot” and the “decisive factor” in the extension of the socialist revolution in Europe.17 However, unable to place his vision within the context of the Ukrainian national revolution or recognise that this latter was an unavoidable and indispensable active force, Rakovsky condemned his own strategy to shipwreck on the rocks of the Ukrainian question. A tragic but relative error if compared with that of Lenin eighteen months later, which plunged the European revolution into the quagmire of the Polish national question by giving orders to invade Poland.

In opposition to the demands of Pyatakov, Rakovsky’s government – which was on paper that of an “independent republic” – considered itself a simple regional delegation of power from the Russian workers’ state. But objective reality is implacable. Faced with Rakovsky’s attempt to impose a Greater Russian communist centralism, the national reality, already explained by Bolsheviks like Shakhrai, and also in their own way by Bolsheviks like Pyatakov, made itself felt. This centralism unleashed powerful centrifugal forces. The proletarian revolution did not lead the national revolution; nor did a proletarian military leadership impose itself at the head of the armed national and social insurrection of the masses. In order to achieve class consciousness, the masses of an oppressed people have first to pass through the stage of achieving a national consciousness. Having alienated and even repressed the bearers of this consciousness, recruitment to the administration was restricted to the often reactionary Russian petty bourgeoisie, who were accustomed to serving under whoever was in power in Moscow. Things were the same for the army; recruitment took place amongst people with a very low level of consciousness, not to say lumpen elements. The result was a conglomerate of disparate armed forces, with commanders ranging from Nestor Makhno (presented by the central press in glowing terms as a natural revolutionary leader of the poor peasants in revolt, overlooking entirely his anarcho-communist beliefs, totally at odds with Bolshevism)18 and straightforward adventurers such as Matvii Hryhoryiv. This latter was promoted to the rank of plenipotentiary Red commander of a vast region by Antonov-Ovseyenko.

The leftist agrarian policy, that of the commune, transplanted into Ukraine from Russia on the principle of a single country and a single agrarian policy, inevitably alienated the middle peasants. It drove them into the arms of the rich peasants and ensured their hostility to the Rakovsky government while isolating and dividing the poor peasants. Power was exercised by the Bolshevik Party, the revolutionary committees and the poor peasants’ committees, imposed from above by the party. Soviets were only permitted in some of the large towns and, even then, had only an advisory role. The most widely-supported popular demand was that of all power to democratically-elected Soviets – a demand of Bolshevik origin that now struck at the present Bolshevik policy. On the national issue, the policy was one of linguistic russification, the “dictatorship of Russian culture” proclaimed by Rakovsky and the repression of the militants of the national renaissance. The Great Russian philistine was able to wrap himself in the red flag in order to repress everything that smacked of Ukrainian nationalism and defend the historical “one and indivisible” Russia. Afterwards, Skrypnyk drew up a list of some 200 decrees “forbidding the use of the Ukrainian language” drawn up under Rakovsky’s rule by “a variety of pseudo-specialists, Soviet bureaucrats and pseudo-communists.”19 In a letter to Lenin, the Borotbists were to describe the policy of this government as that of “the expansion of a ‘red’ imperialism (Russian nationalism)”, giving the impression that “Soviet power in Ukraine had fallen into the hands of hardened Black Hundreds preparing a counter-revolution”.20

In the course of a military escapade, the rebel army of Hryhoryiv captured Odessa and proclaimed that they had thrown the Entente expeditionary corps (in fact in the process of evacuating the town) into the sea. This fictional exploit was backed up by Bolshevik propaganda. Sensing a shift in the wind, the “victor over the Entente”, Hryhoryiv, rebelled against the power of “the commune, the Cheka and the commissars” sent from Moscow and from the land “where they have crucified Jesus Christ”. He gave the signal for a wave of insurrections to throw out the Rakovsky government. Aware of the mood of the masses, he called on them to establish Soviets from below everywhere, and for their delegates to come together to elect a new government. Some months later, Hryhoryiv was shot by Makhno in the presence of their respective armies, accused of responsibility for anti-semitic pogroms. Even the pro-communist extreme left of the social democracy took up arms against the “Russian government of occupation”. Whole chunks of the Red Army deserted and joined the insurrection. The elite troops of “Red Cossacks” disintegrated politically, tempted by banditry, plunder and pogroms.21

These uprisings opened the way for Denikin and isolated the Hungarian Revolution. From Budapest, a desperate Béla Kun demanded a radical change in Bolshevik policy in Ukraine. The commander of the Red Army’s Ukrainian front, Antonov-Ovseyenko, did the same. Among the Ukrainian Bolsheviks, the “federalist” current, in effective agreement with the ideas of Shakhrai and Borotbism, started factional activity. The Borotbists, protective of their autonomy, although still in alliance with the Bolsheviks, formed the Ukrainian Communist Party (Borotbist) and demanded recognition as a national section of the Comintern. With large influence amongst the poor peasantry and the Ukrainian working-class in the countryside and the towns, this party looked towards an independent Soviet Ukraine. They even envisaged armed confrontation with the fraternal Bolshevik Party on this question, but only after victory over Denikin and on the other fronts of the civil war and imperialist intervention.

Both the Hungarian and Bavarian revolutions, deprived of Bolshevik military support were crushed. The Russian revolution itself was in mortal danger from Denikin’s offensive.

“One and indivisible” Russia or independence of Ukraine?

It was under these conditions that Trotsky, in the course of a new and decisive turn in the civil war – as the Red Army went over to the offensive against Denikin – took a political initiative of fundamental importance. On 30 November 1919, in his order to the Red troops as they entered Ukraine, he stated:

Ukraine is the land of the Ukrainian workers and working peasants. They alone have the right to rule in Ukraine, to govern it and to build a new life in it. (...) Keep this firmly in mind: your task is not to conquer Ukraine but to liberate it. When Denikin’s bands have finally been smashed, the working people of the liberated Ukraine will themselves decide on what terms they are to live with Soviet Russia. We are all sure, and we know, that the working people of Ukraine will declare for the closest fraternal union with us. (...) Long live the free and independent Soviet Ukraine!22

After two years of civil war in Ukraine, this was the first initiative by the Bolshevik regime aimed at drawing the social and political forces of the Ukrainian national revolution – that is the Ukrainian workers and peasants –into the ranks of the proletarian revolution. Trotsky was also concerned to counteract the increasingly centrifugal dynamic of Ukrainian communism whether inside or outside the Bolshevik party.

Trotsky’s search for a political solution to the Ukrainian national question was supported by Rakovsky, who had become aware of his errors, and closely coordinated with Lenin, who was also now conscious of the disastrous consequences of policies that he had himself often supported, or even promoted. At the Bolshevik Central Committee Lenin called for a vote for a resolution that made it “incumbent on all party members to use every means to help remove all barriers in the way of the free development of the Ukrainian language and culture (...) suppressed for centuries by Russian Tsarism and the exploiting classes.”23

The resolution announced that in the future all employees of Soviet institutions in Ukraine would have to be able to express themselves in the national language. But Lenin went much further. In a letter-manifesto addressed to the workers and peasants of Ukraine, he recognised for the first time some basic facts. “We Great Russian Communists (have) differences with the Ukrainian Bolshevik Communists and Borotbists and these differences concern the state independence of Ukraine, the forms of her affiance with Russia and the national question in general. (...) There must be no differences over these questions. They will be decided by the alI-Ukraine Congress of Soviets.” In the same open letter, Lenin stated for the first time that it was possible to be both a militant of the Bolshevik Party and a partisan of complete independence for Ukraine. This was a reply to one of the key questions posed a year earlier by Shakhrai, who was expelled from the party before his assassination by the Whites. Lenin furthermore affirmed: “One of the things distinguishing the Borotbists from the Bolsheviks is that they insist upon the unconditional independence of Ukraine. The Bolsheviks will not (…) regard this as an obstacle to concerted proletarian effort.24

The effect was spectacular and had a strategic significance. The insurrections of the Ukrainian masses contributed to the defeat of Denikin. In March 1920 the Borotbist congress decided on the dissolution of the organisation and the entry of its militants into the Bolshevik Party. The Borotbist leadership took the following position: they would unite with the Bolsheviks to contribute to the international extension of the proletarian revolution. The prospects for an independent Soviet Ukraine would be a lot more promising in the framework of the world revolution that on a pan-Russian level. With great relief Lenin declared: “Instead of a revolt of the Borotbists, which seemed inevitable, we find that, thanks to the correct policy of the Central Committee, which was carried out so splendidly by comrade Rakovsky, all the best elements among the Borotbists have joined our party under our control. (...) This victory was worth a couple of good tussles.”25

In 1923, a communist historian remarked: it was largely under the influence of the Borotbists that Bolshevism underwent the evolution from being “the Russian Communist Party in Ukraine” to becoming the “Communist Party of Ukraine.”26 Even so, it remained a regional organisation of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) and did not have the right to be a section of the Comintern.

The fusion of the Borotbists with the Bolsheviks took place just before a new political crisis – the invasion of Ukraine by the Polish bourgeois army accompanied by Ukrainian troops under the command of Petliura, and the resulting Soviet-Polish war. This time the Great Russian chauvinism of the masses was unleashed on a scale and with an aggression that escaped all restraint by the Bolsheviks.

To the conservative elements in Russia this was a war against a hereditary enemy, with whose re-emergence as an independent nation they could not reconcile themselves – a truly Russian war, although waged by Bolshevik internationalists. To the Greek Orthodox this was a fight against the people incorrigible in its loyalty to Roman Catholicism, a Christian crusade even though led by godless communists.27

The masses were moved by the defence of the “one and indivisible” Russia, a mood fanned by propaganda. Izvestia published an almost unbelievably reactionary poem glorifying the Russian state. Its message was that “just as long ago, the Tsar Ivan Kalita gathered in all the lands of Russia, one by one, (…) now all the dialects, and all the lands, all the multinational world will be reunited in a new faith” in order to “bring their power and their riches to the palaces of the Kremlin.”28

Ukraine was the first victim of the chauvinist explosion. A Ukrainian left social democrat, Volodymyr Vynnychenko, who had been the leader of the Central Rada and who had broken with Petluira’s Directory to negotiate alongside Béla Kun a change in Bolshevik policy in Ukraine, found himself in Moscow at the invitation of the Soviet government at the time when many white officers were responding to the appeal of the former commander in chief of the Tsarist army to “defend the Russian motherland” and were joining the Red Army. Georgy Chicherin, at that time Commissar of Foreign Affairs, explained to Vynnychenko that his government could not go to Canossa over the Ukrainian question. In his journal, Vynnychenko writes: “The orientation towards Russian patriotism of the ‘one and indivisible’ variety excludes any concession to the Ukrainians. (…) When one is going to Canossa in front of the white guards (…) it is clearly impossible to have an orientation towards federation, self-determination or anything else that might upset ‘one and indivisible’ Russia.” Furthermore, under the influence of the Great Russian chauvinist tide that was flowing through the corridors of Soviet power, Chicherin resuscitated the idea that Russia could directly annex the Donbas region of Ukraine.29 In the Ukrainian countryside, Soviet officials asked the peasants: “Do you want to learn Russian or Petliuraist at school? What kind of internationalists are you, if you don’t speak Russian?”

In the face of this Great Russian chauvinist regression, those Borotbists who had become Bolsheviks, continued the fight. One of their main leaders, Vasyl Ellan-Blakytny, wrote at the time:

Basing themselves on the ethnic links of the majority of the Ukrainian proletariat with the proletariat, semi-proletariat and petty bourgeoisie of Russia and using the argument of the weakness of the industrial proletariat of Ukraine, a tendency that we describe as colonialist is calling for the construction of an economic system in the framework of the Russian Republic, which is that of the old Empire to which Ukraine belonged. This tendency wants the total subordination of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine to the Russian party and in general envisages the dissolution of all the young proletarian forces of the “peoples without history” into the Russian section of the Comintern. (…) In Ukraine, the natural leading force of such a tendency is a section of the urban and industrial proletariat that has not come to terms with Ukrainian reality. But beyond that, and above all, it is the Russified urban petty bourgeoisie that was always the most important support for the domination of the Russian bourgeoisie in Ukraine.

And the Bolsheviks of Borotbist origin concluded:

The great power colonialist project that is prevailing today in Ukraine is profoundly harmful to the communist revolution. In ignoring the natural and legitimate national aspirations of the previously oppressed Ukrainian toiling masses, it is wholly reactionary and counter-revolutionary and is the expression of an old, but still living Great Russian imperialist chauvinism.30

Meanwhile the far left of the social democrats formed a new Ukrainian Communist Party, called “Ukapist”, in order to continue to demand national independence and to take in those elements of the Borotbists who had not joined the Bolsheviks. Coming out of the theoretical tradition of German social democracy, this new party was far stronger at the theoretical level than Borotbism, which had populist origins and where the art of poetry was better understood than the science of political economy. But its links with the masses were weaker.31 The masses were, in any case, growing increasingly weary of this revolution that was permanent in both a mundane and theoretical sense. Trotsky’s theoretical conception of permanent revolution was not, however, matched, in reality, by a growing over, but by a permanent split between a national revolution and a social revolution. One of the worst results of this was the inability to achieve a united Ukraine (the demand for sobornist´). Lenin’s fatal error in invading Poland exacerbated the Polish national question in an anti-Bolshevik direction and blocked the extension of the revolution. It resulted in a defeat for the Red Army and the cession to the Polish state of more than a fifth of national Ukrainian territory; some other Ukrainian territories were absorbed by Romania and Czechoslovakia.

Every honest historian, and all the more every revolutionary Marxist, must recognise that the promise made by the Bolsheviks during the offensive against Denikin – to convoke a constituent congress of soviets in Ukraine able to take a position on the three options (complete independence, more or less close federal ties with Russia or complete fusion with the latter) put forward by Lenin in his letter of December 1919, was not kept. According to Trotsky, during the civil war, the Bolshevik leadership considered putting forward a bold project for workers’ democracy to resolve the anarchist question in the region under the control of Makhno’s insurrectional army. Trotsky himself “discussed with Lenin more than once the possibility of allotting to the anarchists certain territories where, with the consent of the local population, they would carry out their stateless experiment.”32 But there is no record of any similar discussions on the vastly more important question of Ukrainian independence.

It was only after bitter struggles led at the end of his life by Lenin himself as well as by Bolsheviks like Skrypnyk and Rakovsky, by former Borotbists such as Blakytny and Oleksandr Shumsky, and by many of the leading communists from the various oppressed nationalities of the old Russian empire, that the 12th congress of the Bolshevik Party in 1923 formally recognised the existence in the party and in the Soviet regime of a very dangerous “tendency towards Great Russian imperialist chauvinism”. Although this victory was very partial and fragile, it offered the Ukrainian masses the possibility of accomplishing certain tasks of the national revolution and experiencing an unprecedented national renaissance in the 1920s. But this victory did not prevent the degeneration of the Russian revolution and a chauvinist and bureaucratic counter-revolution that, in the 1930s, was marked by a national holocaust in Ukraine. Millions of peasants died during a famine provoked by the Stalinist policy of pillaging the country, the national intelligentsia was almost completely physically wiped out, while the party and state apparatuses of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic were destroyed by police terror. The suicide of Mykola Skrypnyk in 1933, an old Bolshevik who tried to reconcile the national revolution with allegiance to Stalinism, sounded the death knell for that revolution for a whole historical period.

Tragic errors that should not be repeated

The Russian revolution had two contradictory effects on the Ukrainian national revolution. On the one side the Russian revolution was an essential factor for the overthrow of bourgeois power in Ukraine. On the other, it held back the process of class differentiation amongst the social and political forces of the national revolution. The reason for this was the lack of understanding of the national question. The experience of the 1917-1920 revolution posed in a dramatic fashion the question of the relations between the social revolution of the proletariat of a dominant nation and a national revolution of the toiling masses of the oppressed nation. As Skrypnyk wrote in July 1920: “Our tragedy in Ukraine is that in order to win the peasantry and the rural proletariat, a population of Ukrainian nationality, we have to rely on the support and on the forces of a Russian or Russified working class that was antagonistic towards even the smallest expression of Ukrainian language and culture.”33

In the same period, the new (so-called “Ukapist”) Ukrainian Communist Party tried to explain to the leadership of the Comintern:

The fact that the leaders of the proletarian revolution in Ukraine draw their support from the Russian and Russified upper layers of the proletariat and know nothing of the dynamic of the Ukrainian revolution, means that they are not obliged to rid themselves of the prejudice of the “one and indivisible” Russia that pervades the whole of Soviet Russia. This attitude has led to the crisis of the Ukrainian revolution, cuts Soviet power off from the masses, aggravates the national struggle, pushes a large section of the workers into the arms of the Ukrainian petty bourgeois nationalists and holds back the differentiation of the proletariat from the petty-bourgeoisie.34

Could this tragedy have been prevented? The answer is yes if the Bolsheviks had had at their disposal an adequate strategy before the outbreak of the revolution. In the first place, if, instead of being a Russian party in Ukraine, they had resolved the question of the construction of a revolutionary party of the proletariat of the oppressed nation. Secondly, if they had integrated the struggle for national liberation of Ukraine into their programme. Thirdly, if they had recognised the political necessity and historical legitimacy of the national revolution in Ukraine and of the slogan of Ukrainian independence. Fourthly, if they had educated the Russian proletariat (in Russia and in Ukraine) and the ranks of their own party in the spirit of total support for this slogan, and thereby fought against the chauvinism of the dominant nation and the reactionary ideal of the “gathering together of the Russian lands”. Nothing here would have stood in the way of the Bolsheviks conducting propaganda amongst Ukraine workers in favour of the closest unity with the Russian proletariat and, during the revolution, between the Soviet Ukraine and Soviet Russia. On the contrary, only under these conditions could such propaganda be politically coherent and effective.

There had been an occasion when Lenin tried to develop such a strategy. This is revealed by his “separatist speech” delivered in October 1914 in Zurich. Then he said:

What Ireland was for England, Ukraine has become for Russia: exploited in the extreme, and getting nothing in return. Thus the interests of the world proletariat in general and the Russian proletariat in particular require that Ukraine regains its state independence, since only this will permit the development of the cultural level that the proletariat needs. Unfortunately some of our comrades have become imperial Russian patriots. We Muscovites, are enslaved not only because we allow ourselves to be oppressed, but because our passivity allows others to be oppressed, which is not in our interests.35

Later however, Lenin did not stick to these radical theses. They re-appear, however, in the political thinking of pro-independence Ukrainian communism, in Shakhrai, the Bolshevik “federalists”, the Borotbists and the Ukapists.

We should not, however, be surprised that the Bolsheviks had no strategy for the national revolutions of the oppressed peoples of the Russian Empire. The strategic questions of the revolution were in general the Achilles heel of Lenin himself, as is shown by his theory of revolution by stages. As for Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution, implicitly adopted by Lenin after the February revolution, it was only worked out in relation to Russia, an underdeveloped capitalist country and not for the proletariat of the peoples oppressed by Russia, which was also an imperialist state and a prison house of nations. The theoretical bases of the strategy of permanent revolution for the proletariat of an oppressed nationality appeared during the revolutionary years amongst the pro-independence currents of Ukrainian communism. The Ukapists were probably the only communist party – even if they were never recognized as a section by the Comintern – that openly made reference to the theory of permanent revolution. The basic idea, first outlined by Shakhrai and Mazlakh, then taken up by the Borotbists before being elaborated by the Ukapists, was simple. In the imperialist epoch, capitalism is, of course, marked by the process of the internationalisation of the productive forces, but this is only one side of the coin. Torn by its contradictions, the imperialist epoch does not produce one tendency without also producing a counter-tendency. The opposite tendency in this case is that of the nationalization of the productive forces manifested, in particular, by the formation of new economic organisms, those of the colonial and dependent countries, a tendency which leads to movements of national liberation.

The world proletarian revolution is the effect of only one of the contradictory tendencies of modern capitalism, imperialism, even if it is the dominant effect. The other, inseparable from the first, are the national revolutions of the oppressed peoples. This is why the international revolution is inseparable from a wave of national revolutions and must base itself on these revolutions if it is to spread. The task of the national revolutions of the oppressed peoples is to liberate the development of the productive forces constricted and deformed by imperialism. Such liberation is impossible without the establishment of independent national states ruled by the proletariat. The national workers’ states of the oppressed peoples are an essential resource for the international working class if it is to resolve the contradictions of capitalism and establish workers’ management of the world economy. If the proletariat attempts to build its power on the basis of only one of these two contradictory tendencies in the development of the productive forces, it will be divided against itself.

In a memorandum to the 2nd congress of the Communist International in the summer of 1920, the Ukapists summed up their approach in the following terms:

The task of the international proletariat is to draw towards the communist revolution and the construction of a new society not only the advanced capitalist countries but also the backward peoples of the colonies, taking advantage of their national revolutions. To fulfil this task, it must take part in these revolutions and play the leading role in the perspective of the permanent revolution. It is necessary to prevent the national bourgeoisie from limiting the national revolutions at the level of national liberation. It is necessary to continue the struggle through to the seizure of power and the installation of the dictatorship of the proletariat and to lead the bourgeois democratic revolution to the end through the establishment of national states destined to join the international network of the emerging union of Soviet republics.

These states must rest on “the forces of the national proletariat and toiling masses as well as on the mutual aid of all the detachments of the world revolution.”36

In the light of the experience of the first proletarian revolution, it is precisely this strategy of permanent revolution that needs to be adopted, to resolve the question of the oppressed nations in the framework of the anti-bureaucratic political revolution in the USSR.

As Mykola Khvylovy, Ukrainian communist militant and great writer put it in 1926, Ukraine must be independent “because the iron and irresistible will of the laws of history demands it, because only in this way shall we hasten class differentiation in Ukraine. If any nation (as has already been stated a long time ago and repeated on more than one occasion) over the centuries demonstrates the will to manifest itself, its organism, as a state entity, then all attempts in one way or another to hold back such a natural process block the formation of class forces on the one hand and, on the other, introduce an element of chaos into the general historical process at work in the world.”37

- 1. Published in International Marxist Review, vol. 4, no. 2, 1989, pp. 85-106, and in: M. Vogt-Downey (ed.), The USSR 1987-1991: Marxist Perspectives, New Jersey: Humanities Press, 1993, pp. 235-255.

- 2. Writings of Leon Trotsky (1939-40), New York: Pathfinder Press, 1977, pp. 47-48.

- 3. Ibid., p. 53.

- 4. Ibid., p. 52.

- 5. Ibid., p. 50.

- 6. See one of the most important works on the national question, that of the Ukrainian Marxist R. Rosdolsky, Engels and the “Nonhistoric” Peoples: The. National Question in the Revolution of 1848, Glasgow: Critique Books, 1987.

- 7. See two Marxist interpretations of this revolution, both still banned in the USSR because of their radical incompatibility with the Stalinist Great Russian interpretation of history: M. Iavorsky, Narys istorii Ukrainy, vol. 2, Kiev, Derzhavne Vydavnytstvo Ukrainy, 1924); and M. I. Braichevsky, Priiednannia chy vozzyednannia?, Toronto: Novi Dni, 1972. The latter can be considered as complementary to I. Dzyuba’s famous book Internationalism or Russification?, New York: Monad Press, 1974.

- 8. See the study by M. Volobuiev, which appeared in 1928 and was viciously attacked by the Stalinists: “Do problemy ukrainskoi ekonomiky” in Dokumenty ukrainskoho komunizmu, New York: Prolog, 1962.

- 9. See J. M. Bojcun, The Working Class and the National Question in Ukraine, 1880-1920, Graduate Programme in Political Science, Toronto: York University, 1985, pp. 95-118 [The Workers’ Movement and the National Question in Ukraine, 1897-1918, Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2021]; B. Krawchenko, Social Change and National Consciousness in Twentieth Century Ukraine, London: Macmillan, 1985, pp 1-45.

- 10. On the Marxist debates at the time on the national question, see C. Weil, L’Internationale et l’autre, Paris: L’Arcantère, 1987.

- 11. The classic study – although marked by anti-communist bias – on the establishment of Bolshevik power in Ukraine is that of J. Borys, The Sovietization of Ukraine, 1917¬1923: The Communist Doctrine and Practice of National Self-Determination, Edmonton: CIUS, 1980. See also T. Hunczak ed., Ukraine 1917-1921: A Study in Revolution, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1977. The classic studies on the history of the CP(b) of Ukraine are M. Ravich-Cherkassky, Istoriia Kommunisticheskoi Partii (bo-ov) Ukrainy, Kharkiv: Gosizdat Ukrainy, 1923, and that of M.M. Popov, Narys istorii Komunistychnoii Partii (bilshovykiv) Ukraiiny, Kharkhiv: Proletarii, 1929.

- 12. V. Holubnychny, “Mykola Skrypnyk i sprava sobornosty Ukrainy”, Vpered, no. 5-6 (25- 26), 1952.

- 13. M. M. Popov, op. cit., pp. 139-140, 143-144. The level of tension between the Ukrainian Bolsheviks and the Soviet Russian government can be seen by the following exchange of telegrams from the beginning of April 1918. Stalin, the People’s Commissar for Nationalities to the Skrypnyk government: “Enough playing at a government and a republic. It’s time to drop that game; enough is enough.” Skrypnyk to Moscow: our government “bases its actions, not on the attitude of any commissar of the Russian Federation, but on the will of the toiling masses of Ukraine. (…) Declarations like that of Comrade Stalin would destroy the Soviet regime in Ukraine. (…) They are direct assistance to the enemies of the Ukrainian toiling masses.” (R.A. Medvedev, Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism, New York: Alfred A. Kopf, 1972, p.16.

- 14. V. Skorovstansky (V. Shakhrai), Revolutsiia na Ukraine, Saratov: Borba 1919; S. Mazlakh, V. Shakhrai, Do khvyli, New York: Prolog, 1967. For a (not wholly accurate) English translation of the second book see S. Mazlakh, V. Shakhrai, On the Current Situation in the Ukraine, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1970. Here are some of the questions that these two militants put to Lenin: “Prove to us the necessity of uniting Ukraine and Russia, but do not use the Katerynoslav arguments: show us where we are mistaken, in what way our analysis of the real conditions of life and development of the Ukrainian movement is incorrect; show us on the basis of this concrete example, how paragraph five of the 1913 resolution, that is, paragraph nine of the Communist Program, should be applied – and we will openly and publicly renounce the independence of Ukraine and become the sincerest supporters of unification. Using the examples of Ukraine, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, Byelorussia and Estonia, show us how this principle of proletarian policy – the right of nations to self-determination – has been implemented. Because we do not understand your present policy, and examining it, are apt to seize our heads and exclaim: why did we offer our silly Cossack heads? (…) Now only two answers are possible: either, (1) an independent Ukraine (with our own government and our own party), or (2) Ukraine as Southern Russia. (…) Can one remain a member of the Russian Communist Party and defend the independence of Ukraine? If it is not possible, why not? It is because one is not supposed to defend Ukrainian independence, or because the way we do it is not permitted? If the way we defend Ukrainian independence is not permitted, how may one defend Ukrainian independence and be allowed to remain in the Russian Communist Party? Comrade Lenin, we await your answer! Facts have to be reckoned with. And your answer, just as your silence, will be facts of great import.”

- 15. See I. Majstrenko, Borot´bism: A Chapter in the History of Ukrainian Communism, New York: Research Program on the USSR, 1954.

- 16. Ch. Rakovsky, “Beznadezhnoe delo: O petliurovskoi avantiure”, Izvestia, no. 2 (554), 1919. See also F. Conte, Christian Rakovski (1873-1941): Essai de biographic politique, vol. 1, Lille: Universite Lille III, 1975, pp. 287-292.

- 17. “Tov. Rakovsky o programme Vremennogo Ukraiinskogo Pravitelstva”, Izvestia, no. 18 (570), 1919.

- 18. See A. Sergeev, “Makhno”, Izvestia, no. 76 (627), 1919.

- 19. M. Skrypnyk, Statti i promovy z natsionalnoho pytannia, Munich, Suchasnist, 1974, p. 17.

- 20. F. Silnycky, “Lenin i borotbisty”, Novyi Zhurnal, no. 118, 1975 pp. 230-231. Unfortunately the disastrous policy of the Rakovsky government of 1919 is passed over in silence by P. Broué, “Rako”, Cahiers Leon Trotsky, nos. 17 and 18, 1984, and is hardly touched on by G. Fagan in his introduction to Ch. Rakovsky, Selected Writings on Opposition in the USSR, 1923-1930, London-New York: Allison and Busby, 1980.

- 21. See A. E. Adams, Bolsheviks in Ukraine: The Second Campaign 1918-1919, New Haven-London: Yale University Press, 1963, and J. M. Bojcun, op. cit., pp. 438-472.

- 22. L. Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, vol. 2, London: New Park Publications, 1979, p. 439.

- 23. V.I. Lenin, Collected Works, vol. 30, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1974, p. 163.

- 24. Ibid., pp. 294-296.

- 25. Ibid., p. 471.

- 26. M. Ravich-Cherkassky, op. cit., p. 148.

- 27. I. Deutscher, Trotsky: The Prophet Armed, New York: Vintage Books, 1965, pp.459-460.

- 28. M. Kozyrev, “Bylina o dcrzhavnoi Moskve”, Izvestia, no. 185 (1032), 1920.

- 29. V. Vynnychenko, Shchodennyk 1911-1920, Edmonton-New York: CIUS, 1980, pp. 431¬432.

- 30. Quoted by M.M. Popov, op. cit., pp. 243-245.

- 31. On the history of Ukapism and on pro-independence Ukrainian communism in general the best work is that of J.E. Mace, Communism and the Dilemmas of National Liberation: National Communism in Soviet Ukraine 1918-1933, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1983 [see also Ch. Ford, “Outline History of the Ukrainian Communist Party (Independentists): An Emancipatory Communism 1918-1925”, Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe, vol. 17, n° 2, 2009.]

- 32. Writings of Leon Trotsky (1936-1937), New York: Pathfinder Press, 1978, pp. 426-427. In the period of Gorbachev’s glasnost, it has been stated that this was not only a subject for discussion but also a formal promise – made in bad faith from the start – by the Bolshevik leadership to Makhno. See the article “rehabilitating” the Makhnovist movement by V. Golovanov: “Batka Makhno ili ‘oboroten’ grazhdanskoi voiny”, Literaturnaia Gazeta, no. 6, 1989.

- 33. M. Skrypnyk, op. cit., p. 11.

- 34. Memorandum of the Ukrainian CP in Ukrainska suspilno-politychna dumka v 20 stolitti, vol. 1, New York: Suchasnist, 1983, p. 456.

- 35. This speech is not in the Complete Works of Lenin. It was reported by the press at the time. See R. Serbyn, “Lénine et la question ukrainienne en 1914: Le discours «séparatiste» de Zurich”, Pluriel-débat, no. 25, 1981.

- 36. Memorandum of the Ukrainian CP, op. cit., pp. 449-450.

- 37. M. Khvylovy, The Cultural Renaissance in Ukraine: Polemical Pamphlets, 1925-1926, Edmonton: CIUS, 1986, p. 227.

Ukrainian Marxists, Russian Bolsheviks, and National Liberation: 1900-1921

Eric Blanc

In the face of Russia’s deplorable invasion of Ukraine, we are publishing excerpts on the history of early Ukrainian Marxism, Bolshevism, and the national question from Eric Blanc’s recently published monograph Revolutionary Social Democracy: Working-Class Politics Across Imperial Russia, 1882-1917. Of course, one cannot find solutions to today’s crisis among the stances taken by Marxists a century ago — vast differences in historical context and national development preclude any such copy-and-paste political approach. Nevertheless, the history outlined by Blanc is crucially important for helping make sense of the current conjuncture and its historical roots —

The Editors

National Relations in Imperial Russia