Ruth Fischer: The Ongoing Fascination of the Ultra-left

A Review of Ruth Fischer: Ein Leben mit und gegen Kommunisten (1895–1961) by Mario Keßler

Nathaniel Flakin

Independent Researcher, Berlin, Germany

Mario Keßler, (2013) Ruth Fischer: Ein Leben mit und gegen Kommunisten (1895–1961), Vienna: Böhlau Verlag.

On February 18, 2022, three Stolpersteine were placed at Andreasberger Straße 9 in Britz, in Berlin’s Neukölln district. The brass cobblestones commemorate anyone who was persecuted or killed under the Nazis. These three mark the former home of Ruth Fischer and Arkadi Maslow, and as well as Fischer’s son Friedrich Gerhart Friedländer, until they fled the country in March 1933.

When I announced that I was applying for these Stolpersteine, a comrade responded: ‘Ruth Fischer is a terrible human being. Don’t do it.’ And yes, more than 60 years after her death, Fischer remains one of the most controversial figures from communist history, in Germany or anywhere else. I certainly would not claim her legacy. But it is not as if we were putting up a statue – a Stolperstein merely draws attention to the crimes of the Nazis.

One sign of the ongoing interest in Ruth Fischer is the massive biography by Mario Keßler, published in German in 2013 and weighing in at over a kilogramme. Against the author’s friendly advice, I read it from cover to cover.

Fischer and Maslow are best remembered as the ultraleft leaders of the Communist Party of Germany for a brief period in the mid-1920s.

What makes Fischer so fascinating is her inconsistency. She gained international fame as both a communist and an anticommunist, without lasting success in either role, thus alienating absolutely everyone. As an obituary by the journalist Sebastian Haffner put it, ‘her fate was to unintentionally damage the side she was temporarily aligned with more than the side she was fighting’ (quoted on p. 614; all translations from the work are mine).

Born in Leipzig, Fischer grew up in Vienna as Elfriede Eisler. The Eislers, including her younger brothers Gerhart and Hanns, made up, in the words of Eric Hobsbawm, ‘almost the quintessential Comintern family’ (quoted on pp. 8–9). Subject to myriad forms of antisemitism in the decaying Habsburg monarchy, the three siblings all dedicated themselves to revolutionary modernism, although in very different forms. Elfriede was a firebrand speaker who soon fell out with Stalinism; Gerhart was a party-apparatus man who remained loyal to ‘really existing socialism’; Hanns, a composer, became the most famous of the three.

While she cannot be called the founder of the Communist Party of German-Austria, Fischer did receive membership card #1 of this very small and putschist organisation. One of her earliest works was a pamphlet on the Sexual Ethics of Communism, published in 1920 in Vienna, in which she called for a radical break with the ‘monogamous forced union’: ‘the majority of people live polyamorously’, she wrote, and ‘homosexuality is natural’ (quoted on p. 53). It goes without saying that older and more prudish figures like Lenin and Zetkin were not impressed by this ‘young comrade from Vienna’.

Consistent with these views, Fischer subordinated her family responsibilities to her political duties, and set off for Berlin in 1919, which many saw as the centre of world revolution (‘the reddest of all cities on earth outside the Soviet Union’, in the words of Georg Glaser). While Fischer worked in the Comintern and KPD apparatuses, her son Friedrich Gerhart Friedländer remained in Vienna with both sets of grandparents, and only reunited with his mother a decade later. Berlin is where she met Arkadi Maslow (‘love at first sight’; p. 80), who would remain her personal and political companion until his death two decades later. Within two years, Fischer was the leader of the KPD’s Berlin-Brandenburg district, a bastion of the party’s ultraleft wing that openly defied the leadership. If Lenin described a revolutionary party as an orchestra, then Fischer’s specialty was a one-string banjo: her only theme was rejecting any kind of collaboration with the Social Democrats. Socialist revolution was to be achieved with permanent offensives and revolutionary purity.

Zetkin despised this upstart opposition, whereas Lenin could only shake his head. While many of the leading figures of the ultra-left came from middle-class Jewish families, Fischer was not wrong when she said her faction was ‘not only meshuga students’.

Fischer must have been a uniquely enthralling speaker, since her political profile was not impressive – a lifetime of communist activism left behind only a handful of books. In the words of one contemporary, Ernst Meyer, Fischer’s predecessor as KPD chair, was ‘sometimes quite put out by her political ignorance, claiming that she never even read the Communist Manifesto!’

When the German October collapsed in 1923, dashing hopes for a decisive leap in the world revolution, many rank-and-file KPD members wanted to rid themselves of a leadership that appeared overcautious. The fact that the ultraleft opposition, who had spent years calling for insurrections, had been totally passive during the revolutionary crisis, does not seem to have lessened their appeal. At the party congress of 1924, Fischer and Maslow were swept into the KPD leadership – even against the will of the Comintern Executive, who were aiming for a balance between the party’s different wings.

Thus, at just 28, Fischer became the first woman leader of a mass party anywhere in the world (p. 178; Keßler acknowledges that Luxemburg was also the leader of the KPD between its founding and her assassination two weeks later, but he says that this was not yet a mass party). Technically she was the ‘Chairperson of the Political Secretariat of the KPD’, called ‘Politleiter’ in Comintern-speak. Party chair was a separate, more symbolic post that was held at the time by the worker Ernst Thälmann. But Fischer was the de facto leader of the KPD from 1924 to 1925 – more so because Maslow spent much of this time in prison on trumped-up charges (after the police accused him of stealing a handbag in the park!).

As a party leader, Fischer was able to take her principled refusal to collaborate with Social Democrats to absurd lengths. KPD representatives in parliament were told to avoid shaking hands with their SPD counterparts – or if protocol required it, they were first to put on red gloves. As an ally of Comintern chair Grigory Zinoviev, Fischer led the ‘Bolshevisation’ campaign in Germany, quashing the KPD’s democratic traditions. Fischer argued for ideological monolithism, while Scholem cleared the apparatus of anyone suspected of disloyalty towards the new ultraleft leadership. In just over a year, however, the triumvirate themselves fell victim to the very regime they had created.

If one quote from Fischer is remembered today, it is surely from a speech she gave to far-right university students: ‘Those who call for a struggle against Jewish capital are already, gentlemen, class strugglers, even if they don’t know it. You are against Jewish capital and want to fight the speculators. Very good. Throw down the Jewish capitalists, hang them from the lamp-post, stamp on them. But, gentlemen, what about the big capitalists, the Stinnes and Klöckner?’ (quoted on p. 315).

This is an example of the idiotic attempts of certain Comintern leaders, such as Karl Radek, to appeal to Germany’s Far Right with their hatred of Versailles (the so-called ‘Schlageter Course’). Today, this is often quoted as an example of Communist antisemitism. That is a downright bizarre accusation against a party with a largely Jewish leadership. As Hoffrogge has shown, while there were certainly examples of antisemitic prejudice within the KPD, of all the parties in Weimar Germany the KPD was the most committed to the struggle against antisemitism. Under the Stalinist leadership of Ernst Thälmann, there were even more idiotic attempts to appeal to rank-and-file Nazis, especially with the so-called ‘red referendum’ in Prussia in 1932. Yet bourgeois talk of collaboration between the KPD and the NSDAP is wildly exaggerated.

By 1926, Fischer and Maslow were expelled from the KPD. They were active in a new organisation of the Left Opposition, the Leninbund (Lenin League). But when the KPD’s Central Committee offered an amnesty to anyone willing to renounce their views, the two jumped at the chance to get back into Stalin’s good graces. It did not work: Fischer and Maslow never did get back into the Comintern – but they also never seriously built up a competing organisation. Fischer got a job as a child social worker in the working-class district of Prenzlauer Berg. This is the time the couple lived in Britz, where they were joined in 1929 by Fischer’s son Friedrich Gerhart Friedländer, who attended the Karl Marx School in Neukölln.

In early March 1933, after the Reichstag fire and the Nazis’ rigged elections, Fischer and Maslow fled by motorbike to Czechoslovakia, and eventually made it to Paris. Friedländer was arrested by the SA and detained in an improvised concentration camp for two days before eventually making it to Vienna. (His unpublished autobiography is available in different archives, and contains numerous personal letters from Maslow.) In Paris, Fischer got a job as a social worker in St Denis. The pair met Leon Trotsky several times during his French exile. Trotsky recruited them to the nascent Fourth International, despite the objections of its German section in exile, and they were members for several years under the names Dubois and Parabellum.

After the fall of France, Fischer and Maslow escaped to Portugal. She was able to secure a visa for the US and sailed for New York City; he, with Soviet citizenship, could only make it to Cuba. After half a year, Fischer was able to secure a US visa for Maslow as well. When she called Havana to give him the news, she learned that he had been found dead on the street – likely the victim of a Stalinist assassination, but definitive proof has not been found to this day.

At this point, Fischer made a radical shift. After years as an unaffiliated communist, from one day to the next she transformed herself into a rabid anticommunist. The shock of Maslow’s death was certainly the cause – but equally important was Fischer’s new milieu, in which New York intellectuals were moving rapidly to the right. The former KPD chairwoman famously appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee to denounce her brothers Gerhart and Hanns Eisler, who were both in US exile at that time. She accused them of helping to assassinate Maslow – which, besides going against family loyalty, was also totally preposterous. Gerhart was a communist agent at the time, but was far from the ‘key figure of the American Communist Party’ that his sister made him out to be (p. 424). She received a scholarship from Harvard University to write a book about Stalin and German Communism. Keßler agrees with most other commentators that it is an unreliable and self-serving portrayal of Fischer’s time at the top of the KPD, systematically avoiding any reflection on her role in ‘Bolshevisation’.

This is where the popular understanding of Fischer’s life ends. Yet Keßler shows that she went through another radical shift that opened up a final chapter. He explains this with a single shocking letter. After the war, Fischer was courted by both bourgeois media and secret services as an expert on Stalinism. She received a letter full of praise and an offer for collaboration from Eberhard Taubert, the leader of an anticommunist association in West Germany. She would not have forgotten that Taubert had been a leader of the Nazi stormtroopers (SA) in Berlin, who had detained her son in 1933. This seems to have been a wakeup call: by the early 1950s, Fischer scaled back her collaboration with the FBI and moved to Paris, where she worked as an independent journalist. She was cautiously optimistic about de-Stalinisation in the Soviet Union, and reported favourably on the Bandung Conference to end colonialism. She re-established links with critical communists such as Heinrich Brandler and Isaac Deutscher. After years of wrangling, she was also able to receive a West German pension for her stolen career as a social worker. Fischer died of a heart attack in 1961. She was survived by her son, who had studied mathematics in England and went on to be a university professor.

After 2,000 words’ reviewing Fischer’s life, we must now ask about the political meaning of all this. No one, as far as I am aware, would consider themselves a Fischerite. As a Communist leader, she was feckless, even before becoming a turncoat.

Why, instead of being relegated to a footnote in communist history, have Fischer, Maslow, and Scholem each been the subject of biographies in the past decade? How do we explain the ongoing fascination of the ultra-left? Every history book is a contribution, even if unintentional, to debates about socialist strategy today. Keßler’s biography calls for a ‘democratic communism’ (p. 245) that would reject insurrections and remain on the parliamentary road. There is a kind of ‘Eurocommunism’ that exists among historians. This tendency is pronounced in Alexander Rabinowitch’s unparalleled scholarship concerning the October Revolution. Rabinowitch defends the Bolshevik Party’s right wing, wishing that the Bolsheviks had renounced the spoils of a victorious uprising in order to form a coalition government with all socialist parties.

In Keßler’s study of Fischer, we see this problem in his discussion of the tactics of the united front and especially the workers’ government. In a sense, Trotsky is too popular today. His passionate calls for a united front of communists and social democrats to stop the Nazis make him seem like a Marxist Cassandra. But praise for this tactical proposal is divorced from its strategic context. The antifascist united front is presented as a purely defensive measure – but in defence of what? Bourgeois democracy? For Trotsky, the united front was a tool for a communist party to gather forces for the proletarian revolution (‘an active defence, with the perspective of passing over to the offensive’, as heput it). It was not intended to save bourgeois democracy, but rather to destroy it. A purely defensive conception of the united front has more to do with Käthe Kollwitz, Albert Einstein, or perhaps the SAP than with the Bolshevik-Leninists. Yet this is precisely the vision advocated by many modern historians who are sympathetic to Trotsky.

The workers’ government, as discussed among the Communist International throughout the first half of the 1920s, can only be understood as the culminating moment of the united front. The discussions were contradictory – see Zinoviev’s confusing remarks about the ‘four kinds of workers’ government’ – yet the slogan was always conceived as some kind of step along the road to proletarian dictatorship. Clara Zetkin, for example, who was on the right wing of this debate, said that such a government could only be ‘formed as the crowning effect of a tremendous mass movement, backed by the political organs of proletarian power outside of parliament, by the workers’ councils and by their congress, and above all, by an armed working class.’

Keßler, in contrast, presents such a workers’ government as a parliamentary coalition in contradistinction to proletarian revolution. For him, ‘the only left-wing project that promised success at this time’ was an SPD–KPD government that could have ‘more thoroughly democratised’ Germany (p. 245). For this, the KPD would have needed to develop ‘in the direction of a democratic communism’ and break ‘with every kind of vanguard theory’. In this, he follows Sebastian Haffner in speculating that a democratic but not socialist revolution could have saved Germany from fascism. It is undeniable that the half-revolution of 1918, drowned in blood by the SPD, prepared the ground for Hitler. Yet Keßler and Haffner wonder about a three-quarters revolution which would have left capitalism in place while nonetheless seriously reforming the state apparatus. Rosa Luxemburg once posited that society faced a choice between ‘socialism and barbarism’ – but these historians claim to have found some kind of golden mean between the two.

In response, it is worth quoting Trotsky at some length, who summed up the binary choice posed by the class struggle in Germany in the early 1930s:

That is the situation approaching with every hour in Germany today. There are forces which would like the ball to roll down towards the right and break the back of the working class. There are forces which would like the ball to remain at the top. That is a utopia. The ball cannot remain at the top of the pyramid. The Communists want the ball to roll down toward the left and break the back of capitalism.

Trotsky 1932.

A Review of Call to Arms: Iran’s Marxist Revolutionaries

by Ali Rahnema

Peyman Vahabzadeh

Department of Sociology, University of Victoria, Canada

peymanv@uvic.ca

Ali Rahnema, (2021) Call to Arms: Iran’s Marxist Revolutionaries, London: OneWorld.

Call to Arms presents the latest addition to a trail of literature surrounding the People’s Fadai Guerrillas (PFG, in Persian: Cherikha-ye Fadai-ye Khalq, later the Organisation of Iranian People’s Fadai Guerrillas, OIPFG; ‘fadai’ in Persian means ‘self-sacrificing’) – a self-declared Marxist-Leninist urban-guerrilla group founded in 1971 that, despite its small size and limited operations against the dictatorship of the US-backed Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, captured the political imagination of Iranian dissidents in the 1970s and had an impact on the events that led to the 1979 Revolution. Previous studies on the PFG included a lengthy, two-volume work of ‘research’,

The PFG is not a ‘household’ name among those familiar with the guerrilla movements of the 1960s and ’70s – unlike, say, the RAF in Germany, Tupamaros (MLN-T) in Uruguay, MIR in Chile, or the Brigate Rosse in Italy. This is due to the neglect of the group, until the last decade or so, by Iranian activists and researchers alike. When discussing the PFG in the few existing short engagements (aside from this and the previously mentioned books), Iranian historians, having little interest in registering the PFG as an actor in a global movement, have mostly consigned study of the group to Orientalist ‘Iranian Studies’ frameworks, condemning it to a bygone past.

The PFG was founded in April 1971 as two underground militant groups, having reached the conclusion that only armed struggle could challenge the monarchical dictatorship, merged in the aftermath of security raids. Arising from radical tendencies within the student movement, the two groups emerged from different experiences and influences, with a half-generation age difference between them. The key founders were Massoud Ahmadzadeh, Amir Parviz Pouyan, Abbas Meftahi – from the so-called Group Two, the newer founding group, formed circa 1969–70 –, and Hamid Ashraf – a survivor of the so-called Group One, the older founding group, formed circa 1964 and raided in 1968. Its leaders and theoreticians Bizhan Jazani and Hassan Zia Zarifi were in prison at this time.

Prior to the PFG’s founding, having reorganised and recruited new members, survivors of Group One launched a daring attack on a gendarmerie post in the village of Siahkal in February 1971, declaring war on the regime. 13 members of the group were executed by March of that year. But their bold operation was celebrated by the Iranian opposition as the ‘Siahkal Resurgence’, thus bestowing it with historic importance, and the Siahkal event became a catalyst for more armed struggle. The PFG adopted Marxism-Leninism as its ideology but clearly leaned toward urban-guerrilla warfare, comparable to that of Latin American revolutionaries.

By 1972, of the founding members only Hamid Ashraf had survived: an elusive and capable militant, a meticulous organiser, and beloved leader, he led the group for the next five years, becoming Iran’s most wanted man. Receiving considerable support from student movements inside and outside of Iran, and revolutionary movements and states across the Middle East, between 1971 and 1976 the PFG carried out a number of carefully selected and delivered assassinations, as well as bombings of powerlines and security, military, and police installations. Although it sustained heavy casualties (237 PFG members were killed between 1971 and 1979, while thousands were imprisoned for their connections with the group), the PFG permeated Iranian collective consciousness. Armed struggle gradually polarised Iranian society, contributing to the creation of a collective psychology that contributed to the overthrow of the Shah through a popular revolutionary process in 1978–9. After the revolution, the refashioned OIPFG, now having abandoned armed struggle, emerged as the largest leftist political party, able to hold rallies with as many as 300,000 attending. However, numerous schisms and brutal repression and executions by the Islamic Republic eradicated the group, forcing the remnant cliques of the once formidable Fadai Guerrillas into exile.

There were other militant groups in the 1960s: several Maoist groups most drawn from the student movement abroad were quickly uncovered, and saw their activists jailed; in addition, a vast Kurdish insurgency was repressed in 1968. The PFG, however, must be credited as founder of sustained armed struggle in Iran. This was possible because of its organic relationship with the student movement. The PFG also emerged as a group that other (smaller) militant groups emulated. Appearances notwithstanding, the PFG was an internally diverse group. Under Ashraf’s astute but not ideologically-imposing leadership, it accommodated Marxist-Leninists and Maoists, activists with social-justice rather than ideological motivations, supporters of Ahmadzadeh’s theory, and advocates of Jazani’s theory. He encouraged intra-group discussions and inter-organisational debates, in which he also participated.

The dual origins of the PFG led to the continued presence of two ideological currents. Ahmadzadeh’s theory was the founding and dominant one until around 1974. Influenced by Latin American guerrillas, Ahmadzadeh asserted that armed struggle would create the objective conditions for revolution and soon lead to a popular uprising against the regime. Critical of this view, Jazani produced theoretical works in prison, arguing that armed struggle could not lead to a popular movement without the guerrillas also organising non-militant support networks in factories, workplaces, and universities. By 1974, when many guerrillas could no longer envisage a simmering mass movement, they began questioning the optimism of Ahmadzadeh’s theory, and Ashraf began creating non-militant cells, but this plan fell apart following his death in 1976. When the PFG regrouped afterwards, it lost a significant portion of the organisation – those who rejected armed struggle – in a split. The new PFG adopted Jazani’s theory in 1977, but the revolution left no space for the realisation of Jazani’s ideas and the post-revolutionary OIPFG abandoned the ideas of its founders altogether.

Ali Rahnema’s Call to Arms offers a 500-page history of the group’s formation, its internal debates and issues, and the group’s societal impact in rich detail. I believe that a historian has every right to choose their own approach, as I do not subscribe to ‘objectivist’ historiography and instead hold that history is open to interpretation. Thus, in this review-essay, I will speak of the merits ofCall to Arms, while pointing out critical methodological and theoretical issues and problems caused by Rahnema’s approach.

The book begins with this accurate snapshot:

The Iranian guerrilla movement, through its praxis established a frame of reference, an ethos and an archetype for Iranian political activists. It would be fair to say that its struggle and comportment established a code of conduct for the politicized youth. The battle conducted by the Iranian guerrilla movement captured the imagination of urban Iranians, especially its youth, and confronted them with important political questions on how to engage with authoritarian rule (p. 4).

Wherefore Art Thou Socialism?

A Review of Searching for Socialism: The Project of the Labour New Left from Benn to Corbyn by Leo Panitch and Colin Leys

Matt McManus

Department of Sociology, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

matthew.mcmanus@ucalgary.ca

Leo Panitch and Colin Leys, (2020) Searching for Socialism: The Project of the Labour New Left from Benn to Corbyn, London: Verso.

Introduction

What the [United States] was much more concerned about, even in the wake of the election that brought Mrs. Thatcher to office clearly representing a powerful neoliberal response to the crisis of the 1970s, was the apparent persistence on the Western European Left of radical socialist political alternatives. This was expressed in the strength of the Bennite call for economic democracy inside the Labour Party in the early 1980s…

Panitch and Gindin 2012, p. 196. — Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin, The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire

Socialist Internationalism and the Ukraine War

Socialist Internationalism and the Ukraine War

Rohini Hensman

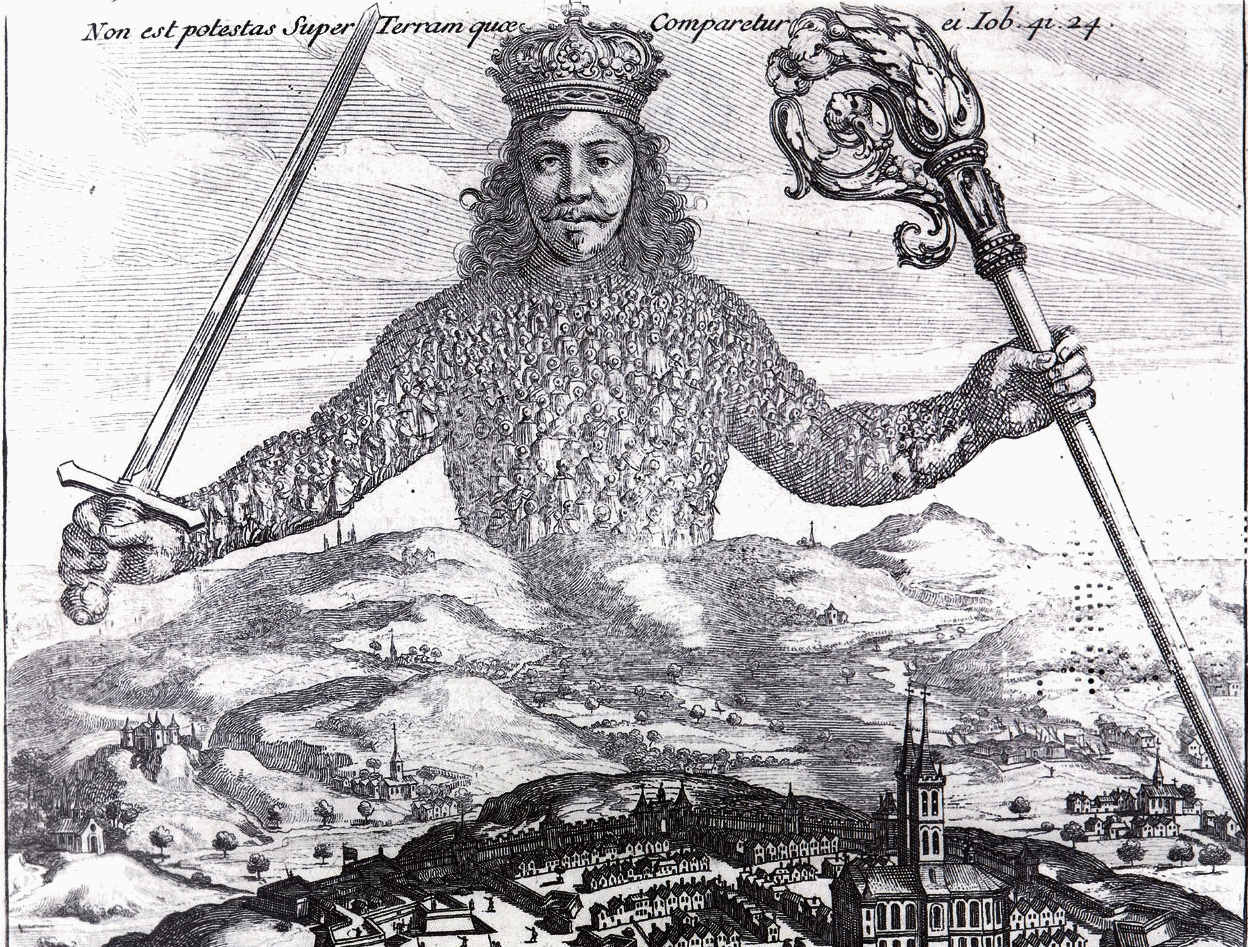

How do the working people of the world transform themselves from a plethora of groups waging a multitude of scattered struggles for survival and dignity to a revolutionary force capable of ending capitalism, governing the earth, and taking over production? They have innumerable tasks before them, but one of the most important is to overcome divisions among themselves resulting from ethnic supremacism and nationalism. Marxists have been debating this issue from the beginning, but it still plagues us today. The war in Ukraine offers a good opportunity to examine it more closely.

The National and Colonial Question

Vladimir Putin’s address on 21 February 2022 was not by any means the first time he cursed V.I. Lenin, but it was perhaps his most extended attack on Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who, he claimed, had created the Ukrainian state

by separating, severing, what is historically Russian land… Lenin’s ideas of what amounted in essence to a confederative state arrangement and a slogan about the right of nations to self-determination, up to secession, were laid in the foundation of Soviet statehood. Initially they were confirmed in the Declaration on the Formation of the USSR in 1922, and later on, after Lenin’s death, were enshrined in the 1924 Soviet Constitution…

Going back to history, I would like to repeat that the Soviet Union was established in the place of the former Russian Empire in 1922. But practice showed immediately that it was impossible to preserve or govern such a vast and complex territory on the amorphous principles that amounted to confederation. They were far removed from reality and the historical tradition.

It is logical that the Red Terror and a rapid slide into Stalin’s dictatorship, the domination of the communist ideology and the Communist Party’s monopoly on power, nationalisation and the planned economy – all this transformed the formally declared but ineffective principles of government into a mere declaration. In reality, the union republics did not have any sovereign rights, none at all. The practical result was the creation of a tightly centralised and absolutely unitary state.

In fact, what Stalin fully implemented was not Lenin’s but his own principles of government. But he did not make the relevant amendments to the cornerstone documents, to the Constitution, and he did not formally revise Lenin’s principles underlying the Soviet Union. From the look of it, there seemed to be no need for that, because everything seemed to be working well in conditions of the totalitarian regime, and outwardly it looked wonderful, attractive and even super-democratic.

And yet, it is a great pity that the fundamental and formally legal foundations of our state were not promptly cleansed of the odious and utopian fantasies inspired by the revolution…1

Putin’s knowledge of the history of the Tsarist empire is not perfect: he seems not to know that the first stable state in Ukraine was Kievan Rus, established by the Scandinavian Varangians, who settled in Kiev in the late ninth century AD, the height of its prosperity occurring under Volodymyr the Great (980–1015 AD), who converted to Byzantine Christianity, and his son Iaroslav the Wise. Its existence as a state therefore predates the establishment of the Grand Principality of Moscow, which later developed into the Russian empire. But Kievan Rus was destroyed by the invasion of Genghis Khan’s Golden Hordes in the thirteenth century, and was subsequently fought over, divided and dominated by Lithuania, Poland, Austria and Russia, until most of it was colonised by Russia in 1654. Nonetheless, there was a revival of Ukrainian culture in the nineteenth century, in the latter part of which both nationalist and socialist parties grew as Ukraine was integrated more closely into the Tsarist empire as a provider of wheat and raw materials such as coal and iron, and as a market for Russian manufactured goods.2 Crimea was incorporated into the empire even later, in 1783, at which time the indigenous Crimean Tatars constituted the overwhelming majority of the population.

However, his recapitulation of post-revolutionary history is relatively accurate: the Soviet Union was indeed established on the territory of the Russian Empire; after the civil war, Lenin wanted it to be a voluntary union between equal Soviet socialist republics; Stalin staged a counter-revolution which Putin approves of, but he failed to cleanse the legal foundations of the state of the ‘odious and utopian fantasies inspired by the revolution’. Perhaps the reason Stalin failed to do so was, partly, as Putin comments, because ‘everything seemed to be working well in conditions of the totalitarian regime’; but another reason is that he was projecting himself as Lenin’s closest comrade and legitimate successor, and therefore could not afford to contradict Lenin openly.

Putin has done us a service by raising the issue of the national and colonial question in this uncompromising fashion, and it is worth going back to examine it again. But, before we do that, a word of caution. The Marxist debate on the national question is confused and confusing, and there are two main reasons:

- Whereas the colonies of the West European imperialist powers were mainly overseas, the Mongol, East European and Ottoman empires colonised adjacent countries, so it was easy to slip into the error of blurring the distinction between the empire and the state. For example, no one would think of India as being part of the British state, but, when Putin sees Ukraine as part of the Russian state, he is by no means alone, nor is this the first time he has done so. As far back as April 2005, he deplored the demise of the Soviet Union as the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century because it left tens of millions of Russians ‘beyond the fringes of Russian territory’.3

- The terms ‘nation’ and ‘nationality’ were used to refer both to a whole country colonised by an imperial power and to what we would today call an ethnic group, and the latter in turn could be based on religious community – for example Jews, whether they were believers or not – or language and national origin, as in the case of Czechs, Hungarians and so on. Even today, terms like ‘ethnicity’ and ‘ethnic minority’ are used in a confusing manner because people who belong to the same ethnic group on one count (say religion) may belong to different ethnic groups on another (say language or national origin). To cut through this confusion, I propose to use ‘ethnicity’ to refer to all these differences: physical characteristics like skin colour, national origin, linguistic community, religious community/sect (whether believers or not), caste and tribe. I will refer to discrimination and violence against people on the grounds of any of these characteristics as ‘ethnic supremacism,’ of which racism is a sub-category. It should be obvious that imperialism presupposes ethnic supremacism: the belief that the people of the country that is subordinated are in some way inferior to the people of the foreign state that dominates them.

There were three main positions in the debate. The first was articulated by those whom Eric Blanc designates as ‘borderland socialists’ from the empire’s periphery: notably Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, the Caucasus and Ukraine, as well as the firmly anti-Zionist Jewish Bund, all of whom sought to tie national liberation and the struggle against ethnic supremacism to a class struggle orientation. For example, in an environment where many socialists took an ambivalent attitude to antisemitism, the Bund called for a joint struggle of Jewish and Christian workers against antisemitic pogroms and opposed Zionist efforts to use the pogroms as a pretext to divide them. In 1900, Lenin denounced Plekhanov’s racist comments about Jews, yet, after a pogrom in 1902, Lenin himself denounced the Bund’s claim that antisemitism had penetrated the working class, despite the fact that the Social Democrats in Odessa had banned Jews from membership in order to avoid alienating antisemitic Russian workers. Only in 1903 did the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party (RSDWP) pass a resolution calling for a resolute struggle against antisemitic pogroms. Borderland socialists also objected to the assumption that after the revolution, the state would remain centralised and Russian would continue to be the state language, as in the Tsarist empire.4

Jews were not the only ethnic group facing racism before and after the revolution. In his monograph on Engels and the ‘non-historic’ peoples, Roman Rosdolsky – chief theoretician of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine and survivor of Auschwitz concentration camp, where he was incarcerated for aiding Jews5 – develops a critique of the way this category was used by Engels during the revolutions of 1848–49 to designate certain East European peoples as counter-revolutionary by nature and doomed to extinction. In it, Rosdolsky cites a similar example from the Russian revolution, when in the cities of Ukraine in 1918–1919, it was not a rare occurrence for Red Guards to shoot inhabitants who spoke Ukrainian in public or admitted to being Ukrainian, because the Russian or Russified rank-and-file party members considered Ukrainian a ‘counter-revolutionary’ language. It was only the strenuous opposition of party leaders Lenin and Leon Trotsky to such conduct that made it possible for the Ukrainian left to form an alliance with the Bolsheviks.6 Marko Bojcun too describes complex interactions of class and ethnicity in his book The Workers’ Movement and the National Question in Ukraine 1897–1918.7

The opposite position was taken by Rosa Luxemburg, who belonged to a minority faction of Polish socialists which opposed Polish independence. She tore apart the ninth point of the RSDWP programme, which said that the party demands a democratic republic whose constitution would ensure, among other things, “that all nationalities forming the state have the right to self-determination,” as being ‘foreign to the position of Marxist socialism’. She agreed with the third clause of the programme, demanding wide self-government at the local and provincial level in areas where minority ethnic communities are concentrated; the seventh clause, demanding equality before the law of all citizens regardless of sex, religion, race or nationality; and the eighth clause, saying that minority ethnic groups would be entitled to schooling in their own languages at state expense and the right to use their languages on an equal level with the state language at assemblies and all state and public functions. But after a long historical exegesis, she came to her main point:

In a class society, “the nation” as a homogeneous socio-political entity does not exist. Rather, there exist within each nation, classes with antagonistic interests and “rights”… There can be no talk of a collective and uniform will, of the self-determination of the “nation” in a society formed in such a manner. If we find in the history of modern societies “national” movements, and struggles for “national interests,” these are usually class movements of the ruling strata of the bourgeoisie, which can in any given case represent the interest of the other strata of the population only insofar as under the form of “national interests” it defends progressive forms of historical development, and insofar as the working class has not yet distinguished itself from the mass of the “nation” (led by the bourgeoisie) into an independent, enlightened political class… Social Democracy is the class party of the proletariat. Its historical task is to express the class interests of the proletariat and also the revolutionary interests of the development of capitalist society toward realizing socialism. Thus, Social Democracy is called upon to realize not the right of nations to self-determination but only the right of the working class, which is exploited and oppressed, … to self-determination.8

In other words, Luxemburg did not see national self-determination as contributing in any way to the self-determination of the proletariat or realising socialism. This is not because she supported imperialist oppression or underestimated the importance of democracy for the working class; on the contrary, already in 1900, in her pamphlet Reform or Revolution, she had said that:

If democracy has become superfluous or annoying to the bourgeoisie, it is on the contrary necessary and indispensable to the working class. It is necessary to the working class because it creates the political forms (autonomous administration, electoral rights, etc.) which will serve the proletariat as fulcrums in its task of transforming bourgeois society. Democracy is indispensable to the working class because only through the exercise of its democratic rights, in the struggle for democracy, can the proletariat become aware of its class interests and its historic task.9

Lenin started out with a very similar position to that of Luxemburg, but, after 1905, started moving closer to the position of the borderland socialists. In his reply to Luxemburg’s objection to clause 9 of the programme, published in April–June 1914, he clarified that support for national self-determination would be only in those cases where bourgeois-democratic national movements existed, and pointed out that

In Eastern Europe and Asia the period of bourgeois-democratic revolutions did not begin until 1905. The revolutions in Russia, Persia, Turkey and China, the Balkan wars – such is the chain of world events of our period in our “Orient”. And only a blind man could fail to see in this chain of events the awakening of a whole series of bourgeois-democratic national movements which strive to create nationally independent and nationally uniform states. It is precisely and solely because Russia and the neighbouring countries are passing through this period that we must have a clause in our programme on the right of nations to self-determination.10

In October 1914, in a speech delivered in Zurich, he said, ‘What Ireland was for England, Ukraine has become for Russia: exploited in the extreme, and getting nothing in return. Thus the interests of the world proletariat in general and the Russian proletariat in particular require that the Ukraine regains its state independence, since only this will permit the development of the cultural level that the proletariat needs.’ However, the Bolsheviks did not develop these insights into a coherent strategy for the oppressed peoples of the Russian empire, leading to avoidable problems during the civil war, but Lenin and Trotsky learned from their mistakes, and, by the end of 1919, were committed to a free and independent Soviet Ukraine.11 Lenin was also influenced by the young Tatar Bolshevik Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev, who argued that the revolution in the Western imperialist countries could not succeed unless it was linked to revolutions in their colonies in the East.12

By contrast with the complete centralisation of power in the Tsarist empire and Russification of its colonies, a series of treaties in 1920–21 recognised Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Finland and Poland as independent states. Byelorussia, Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan became independent Soviet Socialist Republics. In smaller minority ethnic enclaves, local and regional self-government and linguistic and cultural development were encouraged. On 30 December 1922, the First Congress of Soviets of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics approved the Treaty on the Formation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which included the right to self-determination up to the right to secede.13

Before evaluating the positions in this debate, another clarification is necessary. In Part Two on ‘Imperialism’ in Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism, she laments that:

Whether in the form of a new republic or of a reformed constitutional monarchy, the state inherited as its supreme function the protection of all inhabitants in its territory no matter what their nationality, and was supposed to act as a supreme legal institution. The tragedy of the nation-state was that the people’s rising national consciousness interfered with these functions. In the name of the will of the people, the state was forced to recognise only ‘nationals’ as citizens, to grant full civil and political rights only to those who belonged to the national community by right of origin and fact of birth. This meant that the state was partly transformed from an instrument of the law into an instrument of the nation.14

‘Nation’ and ‘nationality’ here means ‘ethnic group’ and ‘ethnicity,’ and the distinction Arendt draws is between the state as guarantor of equality before the law and the state as an instrument of the dominant ethnic group, which can refuse full civil and political rights to other groups. This is indeed inevitable if the state is linked to any particular ethnic community. At best, people from subordinate ethnicities become second-class citizens suffering discrimination and exclusion, at worst, they could be subjected to ethnic cleansing or genocide. This would, by definition, be a state without equal rights for all, and therefore not a democratic republic. Uniting workers in anticapitalist struggles would face the kind of problems faced in South Africa under apartheid. Of course, ethnic supremacism can be rampant even in a democratic republic, but enshrining it in the state makes it exponentially harder to fight.

Coming back to the debate, it is important to start with the positions that all the participants share. They are all Marxist internationalists, who know that capitalism is global and can only be defeated by the working people of the world. They also agree that the working class needs democracy in order to develop the ability to carry out a socialist transformation of society, a position shared by Marx and Engels if we carry out a careful analysis of their writings on the subject.15 It is abundantly clear that Luxemburg opposes linkage of the state in the oppressed nations with any ethnic group, but, if we read carefully, it is clear that the borderland socialists and Lenin too are arguing that ‘national self-determination’ makes sense only where the people of a whole country, in all their diversity, are fighting for freedom from oppression by an imperialist state; today, the term ‘national liberation movement’ or ‘independence movement’ captures this struggle better than the old term ‘national self-determination’. They all agree that where there are enclaves of minority communities, they should have full legal equality with the majority community, linguistic and cultural rights, and rights to local and regional self-government in accordance with the other points in the social-democratic programme. So, there is a large area of overlap between the three parties.

Of course, Luxemburg is right to see nationalism as a bourgeois ideology, affirming as it does that all members of the nation have common interests – defined by the bourgeoisie – which override the common interests of workers of the nation with workers of other countries. What distinguishes her position from the other two is her assumption that the working classes of imperialist states and colonised states can unite in the struggle against capitalism without uprooting imperialism and establishing the independence of the colonies. She fails to realise that ethnic supremacism in the imperialist countries is too often shared not only by sections of the working class but even by self-professed socialists or communists, and can be replaced by respect for the agency and revolutionary potential of colonial peoples only when they have won their freedom. Paradoxical though it may seem, national independence is therefore a necessary step on the road to socialist internationalism.

What this debate reveals is that overcoming nationalism and ethnic supremacism in the working class in order to achieve socialist internationalism is by no means a simple process. Opposition to all imperialisms and support for national liberation struggles is an essential part of it. Combating ethnic supremacism in all imperialist countries is an obvious corollary of this. But what about the nationalism of oppressed peoples? Here, there is a line to be drawn between struggles to establish inclusive democracies in former colonies, which socialists should support because they provide the conditions in which working people can develop the ability to carry out a socialist transformation of society, and attempts by certain colonial elites to monopolise the state on behalf of their own ethnic groups after independence, which socialists should not support because they create enormous obstacles to working-class solidarity, not only with workers in other countries but even with workers from other ethnic groups in their own country. What makes this even more complicated is the fact that inclusive and ethnic nationalism are often intertwined.16 Rosdolsky is surely right when he writes that ‘Just as the working class cannot be socialist or revolutionary a priori, neither is it internationalist a priori … Far from being “by nature without national prejudice,” the proletariat of every land must first acquirethrough arduous effort the internationalist attitude that its general, historical interests demand from it.’17 What made this particularly important for Rosdolsky, and remains equally important for us today, is the potential for ethnic supremacism, when combined with authoritarianism, to become fascism.

From Stalin to Putin

There has been extensive Marxist debate on the characterisation of the state and relations of production in the USSR under Stalin, but much less on imperialism and racism. Yet this was one of Lenin’s greatest concerns when he wrote ‘The Question of Nationalities or “Autonomisation”’, which was part of what came to be called his ‘Last Testament’. After expressing anguish that Orjonikidze, one of Stalin’s close associates, had struck a Georgian communist who disagreed with plans to terminate Georgia’s independent status, he continued,

It is quite natural that in such circumstances the ‘freedom to secede from the union’ by which we justify ourselves will be a mere scrap of paper, unable to defend the non-Russians from the onslaught of that really Russian man, the Great-Russian chauvinist, in substance a rascal and a tyrant.

[…] I think that Stalin’s haste and his infatuation with pure administration, together with his spite against the notorious ‘nationalist-socialism’, played a fatal role here. In politics spite generally plays the basest of roles…

Here we have an important question of principle: how is internationalism

to be understood?

In my writings on the national question I have already said that an abstract presentation of the question of nationalism in general is of no use at all. A distinction must necessarily be made between the nationalism of an oppressor nation and that of an oppressed nation, the nationalism of a big nation and that of a small nation. In respect of the second kind of nationalism we, nationals of a big nation, have nearly always been guilty, in historic practice, of an infinite number of cases of violence; furthermore, we commit violence and insult an infinite number of times without noticing it. [He goes on to quote the racist epithets by which Ukrainians, Georgians and non-Russians in general are insulted.] …

I think that in the present instance, as far as the Georgian nation is concerned, we have a typical case in which a genuinely proletarian attitude makes profound caution, thoughtfulness and a readiness to compromise a matter of necessity for us. The Georgian [Stalin] who is neglectful of this aspect of the question, or who carelessly flings about accusations of ‘nationalist-socialism’ (whereas he himself is a real and true ‘nationalist-socialist’, and even a vulgar Great-Russian bully), violates, in substance, the interests of proletarian class solidarity, for nothing holds up the development and strengthening of proletarian class solidarity so much as national injustice…

The need to rally against the imperialists of the West, who are defending the capitalist world, is one thing. There can be no doubt about that and it would be superfluous for me to speak about my unconditional approval of it. It is another thing when we ourselves lapse… into imperialist attitudes towards oppressed nationalities, thus undermining all our principled sincerity, all our principled defence of the struggle against imperialism. But the morrow of world history will be a day when the awakening peoples oppressed by imperialism are finally aroused and the decisive long and hard struggle for their liberation begins.18

Lenin’s last testament, dictated while he was suffering from the aftermath of two strokes, was suppressed by Stalin, which is not surprising since, among other things, it recommends the removal of Stalin as General Secretary. What comes across is (a) Lenin’s concern that there should be no basis for allegations of double standards in the Soviet Union’s domination of its own colonies while advocating the liberation of Western colonies, and (b) his genuine horror at the imperialist, racist behaviour of Russians and Russified colonials like Stalin and Orjonikidze towards non-Russians. He uses a memorable term – ‘Great-Russian chauvinism,’ which, from the context, sounds like the Russian version of White supremacism – and throws back at Stalin the label he uses to persecute borderland socialists – ‘nationalist socialist,’ i.e., a nationalist pretending to be a socialist – and accuses him of being a racist (Great-Russian) bully.

Lenin’s apprehensions were well-founded. After his death in January 1924 and a brief interregnum, Stalin concentrated absolute power in his own hands, exterminated the rest of the Bolshevik leadership, crushed all dissidence, and launched genocidal assaults on the colonial peoples of the Russian empire, once more Russifying their countries and bringing them under the rule of Moscow. The secret protocols of the Hitler-Stalin Pact signed by Ribbentrop and Molotov on 23 August 1939 effectively made Stalin a Nazi collaborator supplying the Nazis with food and raw materials in return for the go-ahead to recolonise Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and part of Poland. It ended only when Hitler abrogated it by invading the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. The post-war Yalta Agreement allowed him to set up Moscow-dominated regimes in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania and later East Germany. Stalin’s totalitarian state ruling Russia and its colonies was distinguished not only by its extreme brutality but also by a systematic war on the truth, analogous to the Nazi use of the big lie repeated over and over again.19

There is an unmistakeable convergence with fascism in all this, as Hannah Arendt points out in The Origins of Totalitarianism. Indeed, Stalin started collaborating with the Nazis even before the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, sending hundreds of communists to be incarcerated and killed by the Nazis while killing thousands of them himself.20 Snyder describes how Stalin covered up his collaboration with Hitler with the fiction that the ‘Great Patriotic War,’ as he called it, started in 1941, and concealed the fact that Jewish civilians – less than 2 percent of the Soviet population while Russians were more than half – were killed in greater numbers than Russian civilians, thereby creating the impression that Russians were the main victims of the Nazis. Beginning in 1948, Soviet Jews were denounced as ‘Jewish nationalists’ and ‘rootless cosmopolitans,’ demoted, arrested, sent to the Gulag, tortured and executed.21 In fact, the Nazis referred to Ukrainians too in racist terms, as ‘Afrikaner’ and ‘Neger’; during their occupation, ‘roughly 3.5 million Ukrainian civilians, mostly women and children, were killed, and again, roughly 3 million Ukrainians died in the Red Army fighting against the Wehrmacht.’22 These numbers do not include Ukrainians – including Ukrainian Jews like Volodymyr Zelensky’s grandfather – who fought against the Nazis and survived the war. In other words, Soviet Ukrainians were targeted by the Nazis for extermination, and also played a disproportionately large role in fighting against the Nazis, but these facts were concealed by the assumption that ‘Soviet’ meant ‘Russian’.

However, the ideology Stalin espoused in public was Leninism. It was a twisted version – for example, he declared the Soviet Union to be a socialist state, whereas Lenin believed socialism could only be established internationally – but, as Putin complained, he retained elements of Leninist policy, like the right to self-determination, in the constitution. This was necessary to establish his claim to being Lenin’s rightful heir. Moreover, while Stalin and his successors retained a vice-like grip over Russia’s colonies and even invaded and occupied Afghanistan in 1979, they were able to pose as anti-imperialists by supporting liberation struggles in countries colonised by Western imperialism, thus gaining influence in these countries. It would, therefore, not be accurate to call the Stalinist regime fascist, despite the fact that it shared many characteristics with fascism.

Khrushchev and Brezhnev too used Lenin to bolster their claims to leadership, but unlike them, Mikhail Gorbachev was a genuine Lenin scholar, attempting to align his own policies of democratisation through glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) of Soviet society with the revolutionary Lenin, the Lenin who pursued the truth, the internationalist who encouraged development of the languages and cultures of Soviet peoples, and the Lenin who was willing to learn from past mistakes and correct them.23 Gorbachev withdrew Soviet forces from Afghanistan and did not intervene when the Berlin wall came down. He crafted a treaty for a more equal and democratic Soviet Union, but two days before it was due to be signed, hardliners staged a coup against him, put him under house arrest and cut off his communications. There was massive popular opposition to the coup and Boris Yeltsin put himself at the head of it. The coup collapsed and Gorbachev was freed, but he was side-lined by Yeltsin, who presided over the disintegration of the Soviet Union into fifteen independent republics, including the Russian Federation.24

Yeltsin chose Putin to be his successor in 1999, at a time when Yeltsin’s own popularity was in single digits and Putin was the powerful but unknown FSB director. Putin’s way of gaining popularity remains relevant. The Russian Federation still included colonies within it; one of them was Chechnya, which had declared independence in November 1991. Russian troops invaded in 1994, and in an operation directed by the FSB carpet-bombed the capital Grozny and killed the elected president, but guerrilla resistance continued. The new elected president signed a peace deal with Yeltsin, postponing determination of Chechnya’s status. In 1999, a series of apartment bombings in Moscow were blamed on Chechen terrorists but later were found to have been orchestrated by the FSB; they formed the pretext for a ruthless ‘war on terror’ against Chechen civilians including torture, systematic rape and mass murder, murder of its second elected president, and installation of a brutal puppet dictatorship allied to Putin. This was accompanied by a crackdown on human rights defenders and investigative journalists in Russia itself, while witnesses to and investigators of the apartment bombings were assassinated one by one.25 Putin moved rapidly to rebuild an authoritarian state, appointing former KGB and army allies to the security services and expanding their remit, rewriting the rules to give himself the power to appoint and dismiss judges, and gaining new powers to remove and appoint governors and dissolve regional legislatures, until ‘the security services answered solely to the Kremlin. And at the top of the new vertical power sat Vladimir Putin.’26

The Chechen playbook was repeated in Syria after Putin joined the war there in September 2015, the only difference being that Putin’s brutal ally – Bashar al-Assad – was already in power but facing imminent overthrow by a democratic uprising.27 And it gives us a clue what Putin was referring to when he quoted the lyrics from a punk-rock song, ‘Sleeping Beauty in a coffin,’ to tell Ukrainians, ‘Whether you like or not, put up with it, my beauty’:28the fate of Chechnya is what he intended for Ukraine when his armed forces invaded and headed straight to Kyiv in 2022. Apart from Assad, Putin also supports right-wing dictator Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, in return for his regime hosting a satellite monitoring system for intelligence gathering, as well as free use of its ports.29 His Wagner paramilitary has worked for and committed war crimes alongside would-be dictator Khalifa Hafter in Libya,30 and has moved into Sub-Saharan Africa in a big way, backing authoritarian dictators and military coups and committing horrific human rights abuses in return for gold and diamond mining concessions to a related Russian company.31 The left has rightly characterised such practices, when carried out by the West, as imperialism.

Unlike Stalin, who concealed his counter-revolution behind the rhetoric of Leninism, Putin wants to dispense with the whole legacy of the Russian revolution and the ‘odious and utopian fantasies it inspired’. Stalin saw himself in Ivan the Terrible, the tsar who expanded the Russian empire and concentrated absolute power in his hands, and ordered Sergei Eisenstein to make a film about him; but he was angry that Eisenstein portrayed Ivan’s oprichniks – whom Stalin saw as the equivalent of his own secret police – as resembling the Ku Klux Klan, the epitome of American fascism.32 By contrast Putin, who also sees himself in Ivan the Terrible and built a statue of him,33 has no problem linking up with the Ku Klux Klan and other neo-fascists in the US;34 indeed, as Anton Shekhovtsov documents, he has links with neo-fascists throughout Europe.35 Shekhovtsov describes this as a ‘marriage of convenience,’ but there is a much deeper alignment here. Rafia Zakaria points out that ‘Putin’s Russian, or “russkii,” nation is… centered on White, Slavic ethnic Russian superiority’ and endorses discrimination, hate-speech and violence against ethnic minorities and immigrants. She concludes that ‘There are direct parallels here between Putin’s decades-long efforts to elevate white Russians as the leaders of his world order and Hitler’s pursuit of similar ideas of racial purity to realize his own “great nation.”’36 The difference is that Putin seeks to exterminate ethnic minorities only if they resist being subordinated.

The resemblance to Hitler’s ideology is not accidental: Putin is an admirer of the Russian anti-Bolshevik fascist philosopher Ivan Ilyin, who described the ‘spiritual quality’ of Russians as lying in their love for ‘God, motherland and the national vozhd’ [supreme leader], and in 1933 wrote that the ‘spirit’ of ‘German national-socialism’ aligns it ‘with Italian fascism’ and with ‘the spirit of the Russian White movement as well.’37 Putin’s advisor Aleksandr Dugin strategised Ilyin’s orientation for the post-Soviet Russian state in his 1997 book Foundations of Geopolitics, which became required reading in the General Staff Academy and other educational institutions. In it he advocates the recreation of a vast Eurasian empire [the Tsarist Empire/USSR] in which Orthodox Christian ethnic Russians would occupy a privileged position, and outlines a scheme for overcoming ‘Atlanticism’ and establishing global dominance, parts of which have been surprisingly successful. They include destabilising the US by supporting ‘extremist, racist, and sectarian groups’ within it and simultaneously supporting ‘isolationist tendencies’ [Trump]; Eurasian expansion into Latin America; absorbing the Balkans, especially Serbia and ‘Serbian Bosnia’; cutting Britain off from the rest of Europe [Brexit] and ‘Finlandising’ the rest with a strategic use of Russia’s raw material resources [oil, gas]; forming a ‘Grand Alliance’ with Armenia, the ‘Empire of Iran’ and Libya to counter Saudi Arabia and especially Turkey, which should be destabilized by encouraging minorities like the Kurds (whom he characterises as ‘Aryan’ like the Armenians and Iranians) to rebel [links with the PKK]. India and Japan are seen as allies in Russia’s efforts to contain China: the least successful of Dugin’s recommendations.38

In his pursuit of ‘God’, Putin has embraced the fundamentalist Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church, passing misogynist and anti-LGBT+ legislation in accordance with his views. It is obvious why such ideas have made Putin an icon for White supremacists and Christian fundamentalists in the US and Europe: he shares their extreme right-wing rejection of democracy, socialism and feminism.39 In an online presentation, Russian socialist Ilya Budraitskis argued that 20th-century fascists needed a mass movement to smash a strong labour movement and popular social-democratic parties before they could capture state power, and could therefore be characterised as ‘fascism from below’. By contrast, Putin was able to come to power through elections and then transform the state by undermining democratic institutions (for example free and fair elections) and taking away democratic rights (like freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly) – a process that has more or less been completed after the invasion of Ukraine – which could be characterised as ‘fascism from above’.40 Like 20th-century fascism, it makes use of the military, police, secret police and neo-Nazi stormtroopers (whom Putin strategically unleashes and then reins in, instead of allowing them to get too powerful and then slaughtering them like Hitler) and paramilitaries both in Russia and abroad; it uses censorship and state-controlled mass media to propagate the ‘big lie’ (e.g., ‘there is no war in Ukraine, only a special military operation to de-Nazify it’) but also uses methods that were not available to Hitler and Mussolini, such as pro-Kremlin websites, cyberwarfare and troll factories.41 If we identify the core characteristics of fascism as ethnic supremacism, extreme authoritarianism (rejection of democracy), hostility to socialism and communism, social conservatism (hostility to feminism and LGBT+ rights), the cult of the leader and constant propagation of lies, Putin ticks all the boxes.

What this means is that the situation in 2022 is not a throwback to the Cold War as so many commentators have assumed, but more resembles World War II. Perhaps we should recognise it as World War III, a war between ethnic supremacist authoritarianism and democracy, which has engulfed every country in the world, not least the US, the UK and countries of the EU. Ukrainians, who started out fighting for national independence as a democratic republic, have had the misfortune to be thrust to the front lines of a war against genocidal fascism for the second time in living memory. It is true there are Ukrainian fascists, but they are tiny minority compared to the population as a whole waging a people’s war, whereas fascists dominate the Russian side. For socialist internationalists, it is therefore imperative to support a Ukrainian victory and Russian defeat, without which there will be no peace. This includes calling for arms for Ukrainians to defend themselves and sanctions to force Russia to end its aggression, because a victory for national liberation and democracy would create conditions for the advance of the working-class struggle, whereas the victory of imperialist expansionism and fascism would constitute an enormous setback for the working people of the world. Given this context, no one who fails to support the heroic struggle of the Ukrainian people against Putin’s neo-fascism can claim to be a socialist or on the left, because they support imperialism against national liberation, authoritarianism against democracy, barbarism against socialism.

Reactions to the war in Ukraine

While the Russian and Belarussian military forces were massed around Ukraine, a slew of Western commentators blamed NATO’s induction of East European countries, thereby encroaching on Russia’s ‘sphere of influence’, for the crisis. In their worldview, only imperialist powers matter. As Lithuanian socialists explained, the drive for NATO membership actually came from small countries afraid of being re-colonised by Russia,42but such commentators do not care if these countries are swallowed up by imperialism. Their suggestions for a roll-back of NATO to its pre-1997 position is echoed by pseudo-anti-imperialists who support their favourite imperialist and his brutal allies and come out with slogans like ‘Hands off Russia,’ some going so far as to call for blocking arms supplies to Ukraine.43 (By the same logic, the left should have called for Russian workers to block Soviet arms supplies to Vietnam!) Such demands, if implemented, would allow a fascist Putin regime to conquer and rule other East European countries after raping, torturing and killing thousands of civilians in Ukraine, wiping out democracy and setting back the class struggle by decades. They are therefore unambiguously counter-revolutionary and amount to collaboration with imperialism and fascism.

As for the argument that ‘we have to oppose only our own imperialism,’ this makes no sense for internationalists who understand that capitalism can only be defeated by the working people of the world. There may not be much we can do to support the anti-authoritarian struggles of peoples who are not oppressed by our own state, but, at the very least, we can seek and tell the truth about them, and avoid conceptual frameworks based on double standards. The indifference of these people to the bombing of Palestinians in Syria44 and now the bombing of Palestinians in Ukraine45 makes it doubtful that they really care even about Palestinian liberation, unlike Palestinian activists who have highlighted the similarities between the struggles of Palestinians, Syrians and Ukrainians.46 This stance is, above all, a betrayal of the incredibly courageous Russian anti-fascists, socialists, feminists, anti-imperialists and anti-war activists, one of whom said, ‘I now understand how the anti-fascists felt during the Third Reich’.47 Socialists have an obligation to oppose all oppression, regardless of who is the perpetrator and who is the victim.

Unfortunately, they are not the only ones to take retrograde positions on these two struggles (Syria, Ukraine). Artem Chapeye, a socialist who had translated Noam Chomsky’s work into Ukrainian, was aghast at Chomsky’s repetition of Kremlin lies to the effect that the Maidan uprising of 2014 ‘amounted to a coup with US support that… led Russia to annex Crimea, mainly to protect its sole warm-water port and naval base’.48 Syrian Marxist Yassin al-Haj Saleh, who had translated Chomsky’s work into Arabic, was equally critical of Chomsky’s statement that Putin’s intervention in Syria was not imperialist because ‘supporting a government is not imperialism’ – even if that ‘government’ is a dictatorship about to fall to a democratic uprising, and supporting it involves killing 23,000 civilians in six years and getting a port and military bases in return!49 (By that logic, the US intervention in Vietnam was not imperialism, because it was supporting the government of South Vietnam.) Not that Chomsky has any good words to say for Putin or Assad, but his endorsement of the Putin regime’s lies is also a form of support. And the shoddy scholarship of this eminent scholar when he relies on Kremlin propaganda and ill-informed Western commentators to come to his conclusions rather than the work of much more knowledgeable Syrians, Ukrainians and Russians is indeed disappointing, along with his inability to understand that Putin and Assad can manufacture consent for their monstrous crimes by pouring out a constant stream of lies on their captive media and social media while incarcerating and killing anyone who tells the truth. Most depressing of all is his Orientalist portrayal of non-Western peoples struggling against Putin and his allies as dupes of the West and devoid of all agency.

We now have some answers to the question we started with: how do we overcome divisions among working people resulting from ethnic supremacism and nationalism? First, oppose all imperialisms, because apart from their roots in ethnic supremacism they involve national oppression. Second, support struggles for national independence that are predominantly democratic; more authoritarian ones should receive only critical support provided they represent people of all ethnicities. Ethnic definitions of nationhood should never be supported. On the other hand, a socialist programme has to include the rights of ethnic minorities to full equality before the law and their right to have their own language and culture, as well as local and regional self-government, which is important in any democracy but even more so for enclaves where minorities predominate. If socialists are serious about the interests of working people everywhere, then they have to foreground struggles for democracy, which are also struggles against various forms of discrimination and persecution, and this not only in their own countries but in terms of solidarity with the class struggle of workers of all countries. Finally, in a world where hostility to refugees, immigrants and ‘foreigners’ is rampant, internationalists stand for open borders.

Image: "Free Palestine, free Ukraine, free Wi-Fi!" byin_ar23 is licensed underCC BY-SA 2.0.

- 1. Vladimir Putin, ‘Address by the President of the Russian Federation,’ 21 February 2022. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:dlRDC7WGq_4J:en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67828&hl=en&gl=us&strip=1&vwsrc=0

- 2. Orest Subtelny, Ukraine: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press) pp. 25; 32–41; 75–77; 134–35; 227–35; 268–69.

- 3. NBC News, ‘Putin: Soviet collapse a “genuine tragedy”’, 26 April 2005. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna7632057

- 4. Eric Blanc, ‘Anti-imperial Marxism: Borderland socialists and the evolution of Bolshevism on national liberation,’ International Socialist Review, Issue No.100, Spring 2016. https://isreview.org/issue/100/anti-imperial-marxism/index.html

- 5. ‘Auschwitz 75th Anniversary: A memoir by Roman Rosdolsky,’ (First published in Oberona in 1956), https://ukrainesolidaritycampaign.org/2020/01/27/auschwitz-70th-anniversary-a-memoir-by-roman-rosdolsky/

- 6. Roman Rosdolsky, Engels and the “Nonhistoric Peoples: The National Question in the Revolution of 1848, translated and edited by John-Paul Himka, Special Issue of Critique 18–19, 1986, p.165.

- 7. Marko Bojkun, The Workers’ Movement and the National Question in Ukraine 1897–1918, (Leiden: Brill Publishers) 2021. The introduction is available at https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/blog/workers-movement-and-national-question-ukraine-1897-1918-introduction

- 8. Rosa Luxemburg, ‘The Right of Nations to Self-Determination,’ Chapter 1 of The National Question, 1909. https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1909/national-question/ch01.htm

- 9. Rosa Luxemburg, ‘Reform or Revolution,’ Chapter 8, 1900. https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1900/reform-revolution/ch08.htm

- 10. V.I. Lenin, ‘The Right of Nations to Self-Determination,’ Chapter 3, April-June 1914. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1914/self-det/ch03.htm

- 11. Zbigniew Kowalewski, ‘For the independence of Soviet Ukraine,’ https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/blog/for-independence-soviet-ukraine

- 12. Rohini Hensman, Indefensible: Democracy, Counter-Revolution and the Rhetoric of Anti-Imperialism, (Chicago: Haymarket Books), pp.59–61 (includes references).

- 13. Urs W. Saxer, ‘The Transformation of the Soviet Union: From a Socialist Federation to a Commonwealth of Independent States,’ Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review, Vol.14 No.3, 7.1.1992, pp.581–715.

- 14. Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, (New York: Harcourt Publishing Company) 1976, p.230.

- 15. Rohini Hensman, ‘Marx and Engels on Socialism and How to Achieve It: A Critical Evaluation,’ in Gregory Smulewicz-Zucker and Michael J. Thompson (eds.) An Inheritance for Our Times: Principles and Politics of Democratic Socialism, (New York: OR Books) 2020, pp.131–147.

- 16. Sri Lanka, formerly Ceylon, is an example of ethnic nationalism in a former colony, leading to a devastating civil war and the decimation of a once-strong labour movement; see Rohini Hensman, ‘Post-war Sri Lanka: Exploring the path not taken,’ Dialectical Anthropology 39, 2015, pp.273–293.

- 17. Rosdolsky 1986, pp.182–183, emphasis in original. The quotation which Rosdolsky is disagreeing with is from F. Engels, ‘Das Fest der Nationen in London,’ 1845.

- 18. V.I. Lenin, 1922, ‘The question of nationalities or “autonomisation”’, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1922/dec/testamnt/autonomy.htm

- 19. Rohini Hensman, Indefensible, pp.35–37, 63 (references included).

- 20. Alex de Jong, ‘Stalin handed hundreds of communists over to Hitler,’ Jacobin, 22 August 2021, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2021/08/hitler-stalin-pact-nazis-communist-deportation-soviet

- 21. Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (London: Penguin Random House) 2010, pp.339–351, 363–368.

- 22. Timothy Snyder, ‘Germans must remember the truth about Ukraine – for their own sake,’ Eurozine, July 7, 2017 https://www.eurozine.com/germans-must-remember-the-truth-about-ukraine-for-their-own-sake/

- 23. Christopher Smart, ‘Gorbachev’s Lenin: The myth in service to “Perestroika”’, Studies in Comparative Communism, Vol.23, No.1 (Spring 1990), pp.5–21.

- 24. Bridget Kendall, ‘New light shed on anti-Gorbachev coup,’ BBC News, 18 August 2011. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-14560280

- 25. Rohini Hensman, Indefensible, pp.66–71 (including references.)

- 26. Chris Miller, Putinomics: Power and Money in Resurgent Russia, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press) 2018, pp.26–27.

- 27. Jackson Diehl, ‘Putin is going by a familiar playbook in Syria,’ Business Insider, 12 October 2015. https://www.businessinsider.com/putin-is-going-by-a-familiar-playbook-in-syria-2015-10?IR=T

- 28. Michele A. Berdy, ‘A Russian Sleeping Beauty,’ The Moscow Times, 11 February 2022. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2022/02/11/a-russian-sleeping-beauty-a76338

- 29. Octavio Enrìquez, ‘Ortega, the “anti-imperialist”, surrenders to Russian interests,’ Confidencial, I March 2022. https://www.confidencial.com.ni/english/ortega-the-anti-imperialist-surrenders-to-russian-interests/

- 30. Al-Monitor Staff, ‘Intel: EU sanctions suspected head of Russia’s Wagner paramilitary group,’ Al-Monitor, October 15, 2020 https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2020/10/eu-sanction-russia-wagner-yevgeniy-prigozhin.html

- 31. Peter Fabricius, ‘Wagner’s dubious operatics in CAR and beyond,’ Institute for Security Studies, 21 January 2022. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/wagners-dubious-operatics-in-car-and-beyond

- 32. Alexey Timofeychev, ‘“Disgusting thing!” Why Stalin couldn’t accept Eisenstein’s sequel of “Ivan the Terrible”’, Russia Beyond, 9 January 2018. https://www.rbth.com/history/327217-ivan-terrible-stalin-eisenstein

- 33. Howard Amos, ‘Russia falls back in love with Ivan the Terrible, Politico, 31 October 2016. https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-falls-back-in-love-with-ivan-the-terrible-statue-monument-oryol/

- 34. Natasha Bertrand, ‘“A model for civilization”: Putin’s Russia has emerged as “a beacon for nationalists” and the American alt-right,’ Business Insider, December 10, 2016. https://www.businessinsider.in/politics/a-model-for-civilization-putins-russia-has-emerged-as-a-beacon-for-nationalists-and-the-american-alt-right/articleshow/55913352.cms

- 35. Anton Shekhovtsov, ‘The Kremlin’s marriage of convenience with the European far right,’ OpenDemocracy, 28 April 2014. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/kremlins-marriage-of-convenience-with-european-far-right/

- 36. Rafia Zakaria, ‘White Russian Empire: The racist myths behind Vladimir Putin’s power grabs,’ The Forum, 10 March 2022. https://www.aapf.org/theforum-white-russian-empire

- 37. Anton Barbashin, ‘Ivan Ilyin: A fashionable fascist,’ Riddle, 20 April 2018. https://ridl.io/en/ivan-ilyin-a-fashionable-fascist/

- 38. John B. Dunlop, ‘Aleksandr Dugin’s Foundations of Geopolitics,’ Stanfod: The Europe Center, 2004. https://tec.fsi.stanford.edu/docs/aleksandr-dugins-foundations-geopolitics

- 39. Carl Davidson and Bill Fletcher Jr., ‘Putin is attempting to center Russia as a hub of the global right wing,’ Portside, 30 March 2022. https://portside.org/2022-03-30/putin-attempting-center-russia-hub-global-right-wing

- 40. Presentation at an event called ‘Inside the Aggressor,’ 27 March 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpyzmIg7v5g Budraitskis’s presentation starts at 38.00.

- 41. Alexander Zemlianichenko, ‘Putin’s fascists: the Kremlin’s long history of cultivating homegrown neo-Nazis,’ The Conversation, 21 March 2022.