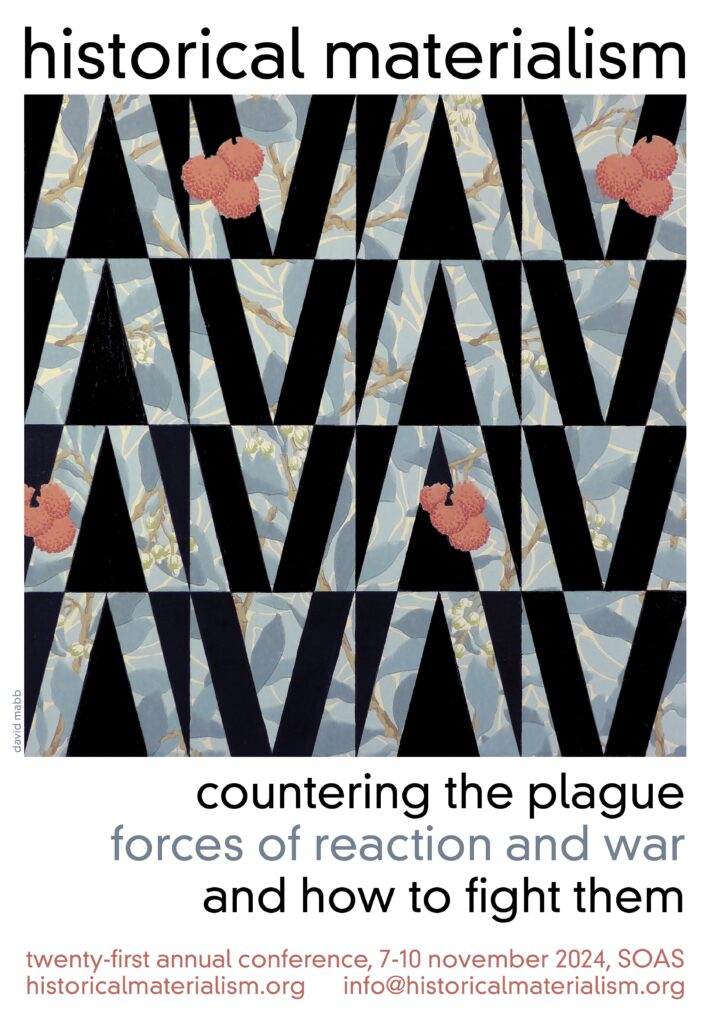

Western Marxism Stream Call for Abstracts – Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Workers’ Inquiry Stream Call for Abstracts – Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Call for Abstracts: Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Countering the Plague:

Marx, Engels & Theology: Roland Boer

The Marxism and religion debate has returned with renewed vigour of late. We need to remind ourselves that by ‘religion’, Marx and Engels usually meant the dominant form of religion in Europe: Christianity, although they also discuss Judaism. On this question, the full range of texts by Marx and Engels on theology are rarely discussed. The reason is that early in the debate a few texts were chosen as a ‘canon within the canon’, leaving many other texts out in the cold.[1] In order to bring attention to those writings, I offer this annotated bibliography, organised according to the main religious themes discussed by Marx and Engels. The following collection begins with Marx, drawing occasionally on joint works with Engels, before focusing in the last two sections on Engels’s life-long interest in religion.