HM London Conference 2017

HM at 20 and 16

For the journal's 20th anniversary, we repost here extracts of interviews with Esther Leslie for HM in 2017 and with Peter Thomas for Jacobin in 2004, both conducted by George Souvlis.

HM London 2017: Revolutions Against Capital, Capital Against Revolutions?

9-12 November at the SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) Main building, Russell Square (more details below).

*** ONLINE REGISTRATION IS NOW CLOSED. PLEASE REGISTER AT THE DOOR ***

*** DRAFT PROGRAMME NOW ONLINE ***

*** ABSTRACTS AVAILABLE HERE ***

*** FULL INTERVIEW WITH EDITOR ESTHER LESLIE ***

EXTRACTS OF NEW INTERVIEW WITH ESTHER LESLIE BY GEORGE SOUVLIS - HM AT 20 - 6 NOVEMBER 2017

GS: Now let's discuss a bit the Historical Materialism initiative, now in its twentieth year, in which you are one of the founding members. Let’s begin with how the publication of the journal of Historical Materialism began. What were the initial aspirations for it? Could you mention some continuities and discontinuities in the twenty years history of the journal?

EL: I was not there right at the beginning. I was brought in before the first issue appeared though, so while not a founder, I have been involved since the journal has been in existence. We were initially self-published, did it all ourselves, including putting the journal in envelopes in my living room. The partnership with Brill has changed that and imposed on us a certain regularity, mechanized processes, and it has professionalized certain aspects - paying a copy editor, for example. We inhabit also a different environment of scholarly journals and online publishing nowadays. But I don’t think those changes have fundamentally altered the way in which we come together as a group of editors and discuss each article sent to us, commission reviews, argue over the direction of the journal, the necessity or not of a certain piece. I believe we wanted a journal which could represent the variety of ways in which Marxism could be brought to bear on aspects of the world. We did not want to be stuck in disciplinary silos but thought that one of the more brilliant things about Marxism is how it refuses those divisions, or if it does not refuse them, it becomes stupid. I am not claiming that we do not publish Fachidioten in the journal, of course, but the aspiration at the start was to publish articles that emerged from a Marxist perspective and could be read by anyone who was engaged in that mode of thinking – or interested to learn more about it - and acting, irrespective of theme. We wanted to represent the work of both the established scholars in Marxism and a younger or newer generation. We had aspirations to be the leading Marxist journal. We have tried to be supra-sectarian – and have weathered some difficult moments as groups on the Left around us have collapsed, gone rotten, recomposed, been riven apart. The board has constantly replenished itself, which has been a good thing, bringing in international perspectives, which enabled us to not get too embroiled in the catastrophic moves of parts of the UK Left. Perhaps it means that there is little collective memory of what we have been – but that is not a bad thing. Why look back, to glorious or inglorious pasts? One continuity has been the provision of covers by Noel Douglas. 20 years of covers is an achievement – but then these covers are also a tracking of the political events, highs and lows, in the world and so form in themselves a museum of world struggles, wins and defeats.

GS: Another significant aspect of the Historical Materialism project is the conferences that it organises and which have a global character, considering that they are now held annually in four continents (India, Europe, Australia, USA/Canada). Would you like to comment on the origins of this and its transformation through time?

EL: The conference began in 2004. It was much smaller, of course. It was even more chaotic than it is nowadays - we have learnt much about event planning and have been lucky to have been aided by some formidable organisers – always women. The conference grew in the subsequent years and is perhaps stable in terms of numbers now, but we always hope for expansion, for more people than we could possibly cope with, because for us, unlike other conferences, our conference is some sort of gauge of the significance, resonance, importance of our mode of comprehension, of Marxism in the world. We like to think that the conference is a must-do event for the global Left and enjoy the buzz of people meeting and re-meeting, quite apart from the papers that are delivered. It is not easy to organize and we do not really have institutional support, so it is in many ways done from the bottom up, which is why people should give us some slack if things do not run perfectly. The conference is franchised, so to speak now, with satellite events happening in other countries. I hope that means that the space for committed, intelligent Marxist work has expanded in the world and perhaps we have contributed to that. We have also learnt from that expansion, and from the drawing in of international voices. We are conscious that there is much beyond the Western tradition and also we have turned more attention to questions of sexuality and gender in later years.

GS: The conferences have succeeded at creating a new solid radical milieu around them. What else has HM accomplished?

EL: There is the book series, which has felled quite a few forests, and also, hopefully, circulated and recirculated some important materials. Some of the books in the series have been honoured with the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher prize, as recognition of their import. HM has kept Marxism as a point of attraction through years in which the Left has been, as ever, under assault, including from within its own ranks. To be able to meet together, hear each other, discuss, make future plans, develop projects, is positive.

Maia Pal: Not everyone on the radical left is a fan of anniversaries, perhaps considering their often stale and fixed look back into the past. This year's HM conference set out to celebrate a few - the centenary of the Russian Revolution, the publication of Marx's Capital, the journal's birth... What do you think this says about the HM project, the left in general and the topic of memory your work generally explores? Finally, could you say something about your paper for this year's London conference, 'Lenin and the body in memorialis and the ecstatic sexuality in Eisenstein's film' which perhaps explores this desire to keep the revolutionary past alive?

EL: The celebration of anniversaries is usually reactionary. As I said earlier, why look back on glorious or inglorious pasts? Of course, I also take from Benjamin the idea that we have to hold onto the tradition of the oppressed, have to keep the red thread, the weak messianic force of resistance going, because otherwise the only story, or history, that remains is that of the victors. Much celebration is celebration by the victors. The monument to Benjamin in Port Bou, where he committed suicide, is to some extent sensitive to this. The memorial by Dani Karavan is in the idiom of the post-conceptual memorial as artwork. A narrow shaft leads one down to the perilous sea, in order to make us think about loss, danger, death. Etched on the glass of the memorial is, in several languages, a phrase from Benjamin, which observes: ‘It is more arduous to honour the memory of the nameless than that of the renowned. … Historical construction is devoted to the memory of the nameless.’

There is another intriguing history of memorialisation in Port Bou, occulded by this grander, European gesture. In 1979 a little plaque in Catalan was set in the cemetery wall. It reads ‘A Walter Benjamin – ’Filòsof alemany – Berlin 1892 Portbou 1940’, and in the context of post-Franco Spain appears to hint at the possibility and necessary recovery of a non-Fascist German tradition. Inside the cemetery too is another memorial stone, this time from 1990. It bears a very famous line from Benjamin: ‘Es ist niemals ein Dokument der Kultur, ohne zugleich ein solches der Barbarei zu sein’, then in Catalan: ‘No hi ha cap document de la cultura que non ho sigui també de la barbàrie’. In English this line from ‘On The Concept of History’ reads, according to the Selected Writings, ‘There is no document of culture which is not at the same time a document of barbarism’. Monuments to civilisation and culture are frequently also monuments to barbarism. Benjamin is clear, taking his line from Marx, that the oppressed are constantly robbed of their history and their memory is always ‘in danger’ of eradication, undermined, ‘in favour of the grand and official narratives of power, the ‘triumphal procession in which today’s rulers tread over those who are sprawled underfoot’, whereby historical memory is ‘handed over as the tool of the ruling classes’. In the preparatory note for ‘On the Concept of History’, he criticizes historical recounting that depends on recounting the antics of glorious heroes of history in monumental and epic form, and is in no position to say anything about the ‘nameless’, those who are the toilers in history, as much as those who suffer the effects of historical agency. His own mode of ‘historical construction is devoted to the memory of the nameless.' It is able to remember the repressed of history who were its victims and its unacknowledged makers.

Benjamin constructs a re-visioning of the past, wherein the historian bears witness to an endless brutality committed against the ‘oppressed’. This, he understands to have been Marx’s task in Das Kapital. Das Kapital is a memorial, an anti-epic memorial, pulsating in the present, insisting on redress. Marx’s sketch of the lot of labour is presented as a counter-balance to the obfuscation of genuine historical experience. Marx memorializes the labour of the nameless, whose suffering and energy produced ‘wealth’ in the vast accumulations of commodities.

What interests me here is the ways in which we might think of what could be called counter-memory or counter-memoralisation not just as the acknowledgement of an alternative mode of understanding the past, but also as an ongoing necessity, that we are constantly steered away from knowledge of our own experience. The First World War was, for Benjamin, one marker of this: in it experience tumbles in the old style, no longer matching life or language. He writes: ‘For never has experience been contradicted so thoroughly: strategic experience has been contravened by positional warfare; economic experience, by the inflation; physical experience, by hunger, moral experience, by the ruling powers.’

We of all people are aware of Lenin’s thoughts on commemoration, as evinced in his degree from 12 Apr. 1918, titled ‘On Removing Monuments Erected in Honor of Tsars and Their Servants and Developing a Project for Monuments Dedicated to the Russian Socialist Revolution (On Monuments of the Republic)’. This provided for the removal of monuments that had apparently no historical or artistic value, as well as for the creation of works of revolutionary monumental art, which took one of two forms: – (1) decorating buildings and other surfaces ‘traditionally used for banners and posters’ with revolutionary slogans and memorial relief plaques; (2) – vast erection of "temporary, plaster-cast" monuments in honour of great revolutionary leaders. These monuments were created mainly as temporary works – Lunarcharchsiki recalled Lenin stating that the monument should be not of marble, granite and gold lettering, but instead of inexpensive materials (plaster of Paris, concrete, wood). Based on the frescoes in Campanella’s City of the Sun, these were to be educational, hinges for discussion in the city, occasions for learning – each unveiling was to be the occasion for a little holiday, a lecture.

Alternatively, we could think of Debord. Debord made an extraordinary book in 1959 called Memoires with the artist Asger Jorn, famously covered in sandpaper to scar the books in its proximity on the shelf. Memoires begins with a quotation from Marx: ‘Let the dead bury the dead, and mourn them.... our fate will be to become the first living people to enter the new life.’ It is comprised of two layers, emulating the layers of memory. One layer has black ink that outlines newspaper snippets, graphics from magazines, maps of Paris and London, images of war, reproductions of old artworks, pictures of friends, hoodlum girls, people in their milieu, and the occasional thought or question from Debord. The other layer is splattered coloured inks, which lead paths from or overlap with the black inked layer. Memory is obscure, invaded, fragmented, on the cusp of disappearance. It is abrasive, cut up, destructive, involuntary – in the mode of Proust, dispersed. For the reader there is only a drift, a wandering path, with no assured meaning, a place for rag pickers rescuing the detritus of life. Countering the regimentation of time in work and the straight-ahead narrative, this book squanders time, in emulation of ruling class leisure and luxury. There are constellations, moments, evanescent points that flare up in the memoir and burn out again to be forgotten, as much as remembered.

The situationists knew that conventional forms of historical memorialization risked partaking in the society of the spectacle’s reification of everyday life. Magnificent monumentalization offered a historical survival not worth living. But they did not wish for their own erasure. They developed new strategies of memorialization, liquid ones, and as Frances Stracey puts it: ‘those commemorated were not reduced to a dead correlate of the present, frozen in perpetuity, but salvaged in a more revitalized form, ideally as a constantly shifting, eruptive force in the present and for the future.’ Our memorials should aim at being such. My paper at the conference thinks about the ways in which film, film of a cream separator, film of a twirling ceramic pig, and film of Lenin, might speak to these concerns, might speak into a world, the Soviet one, in which Lenin’s body was frozen, hardened, its dissolution counteracted in death, supposedly for ever more. It was a wrong-footed hope, but it was emblematic of the sclerosis of the state. Sometimes forgetting might be better. Sometimes remembering differently might be advised. Keeping things alive is a kind of art, if it is not to be a cult.

******************************************************************************************

AN INTERVIEW WITH PETER D. THOMAS BYGEORGE SOUVLIS

Peter D. Thomas is a lecturer in the history of political thought at Brunel University, London. He is the author of The Gramscian Moment: Philosophy, Hegemony and Marxism. He is a member of the HM editorial board and co-editor of the Historical Materialism Book Series.

The interview was conducted by George Souvlis, a PhD candidate in history at the European University Institute, Florence.

GS: Let’s begin with how the publication of the Journal of Historical Materialism began. What were the initial aspirations for it?

PT: The journal began in the late 1990s, emerging out of different seminars attended by young postgraduate students — so, largely people writing PhD dissertations — who fortuitously came together to set up the project. It was initially a rather modest project of establishing a journal where there could be debates and discussions of topics in Marxist theory, after the long seasons of “post-Marxisms.” The journal really entered into a phase of international expansion through coming into contact with people from many different countries who were studying in London or had different connections with London.

These people became involved in the broader project of Historical Materialism and gradually there emerged a development of the journal beyond the boundaries of the English-speaking world, with a very strong focus on international discussions. In other words, we attempt to rebuild some of the bridges to other left-wing and Marxist cultures in other languages which had existed previously in the 1960s and 1970s but which have been lost for generational reasons in the 1980s and early 1990s.

I can’t speak for other members of the editorial board, but in my personal view, the fundamental rationale behind the journal was a commitment to a non-sectarian approach to developing a broad forum of discussion for all of those who identified with the Marxist tradition or the Marxist traditions in many different senses. The project soon developed in the direction of an ongoing self-critique of Marxist knowledge.

The rediscovery of old debates, the initiation of new debates and the attempt to develop a type of research project for contemporary Marxist theory became our central concerns.

GS: Could you mention some continuities and discontinuities in the sixteen-year history of the journal?

PT: There have been many continuities in the journal in terms of our focus on encouraging international discussion and always reaching out to other areas of the world and comrades working in languages other than English. Another important continuity is the strong pedagogical focus of the journal; the journal is very much dedicated not simply to publishing the big stars or the established scholars but also to encouraging younger scholars and new emerging research projects.

Another element of continuity is our commitment to non-sectarian discussions and debates. We take very seriously the idea that theoretical debates in the Marxist tradition need to be conducted with the highest standards of scholarly rigor, rather than descending into slanging matches and ritualized abuse. This involves people, without negating their own political commitments, learning new ways of discussing and debating those commitments, beyond the sometimes very polemical and conflictual environments of militant politics.

So, we see ourselves very much as a necessary continuation of politics, albeit at a certain enabling distance. We certainly do not promote an academisist form of Marxism, whatever that may be.

At its best, HM has functioned as a complement to existing political debates and sometimes has helped to create a type of “demilitarized” space for productive scholarly and theoretical conflicts, rather than the destructive conflicts that sometime develop under the pressures of the conjuncture and the urgency of certain forms of militant politics.

The discontinuities are also noticeable. There have been different generations or phases of involvement on the editorial board. Some people for different reasons decided to become engaged in other projects or found their interests moving in other directions. We are thus always looking for the involvement of new members of the editorial board, seeking to connect with younger generations and thus developing an ongoing transmission of the political culture we have tried to develop.

GS: What do you think is the position of the journal in relation to other Anglophone left-wing journals/magazines like New Left Review, Socialist Register, Red Pepper, or Jacobin?

PT: All of these journals are committed to broad discussions on the Left in different ways, and I think they should all be seen as complimentary elements of the broader contemporary left-wing and Marxist culture. In my personal view, I would suggest that one of the distinctive features of Historical Materialism is that we aim very seriously not at being an academic journal in a narrow professional sense, but at being a serious scholarly research journal.

Thus, the majority of the articles we publish are serious research papers that have emerged from long-term research projects; engagement with immediate political disputes or with contemporary political issues may very well figure in such articles, but that is not usually the primary focus. There is a certain “time” of theory, or temporality of theoretical practice, as Louis Althusser would have said, and we have tried to respect that temporal dimension, to enable the space for reflection and theoretical elaboration.

In terms of our relations with other Marxist journals in English, which I think also includes many other journals in addition to those you mention, such as Rethinking Marxism andScience and Society in United States,Thesis Eleven in Australia,Capital and Class in the UK, and so on, I think members of the editorial board ofHM regard those journals as our comrades and collaborators in building a new left-wing theoretical culture of discussion and debate.

The focus of Historical Materialism, however, is in my view unapologetically theoretical, in a scholarly rather than academic sense, rather than directly interventionist (other members of the editorial board have different perspectives on this question — my comments should not be taken as an “official” position of the editorial board, which does not exist). I think that theoretical work, serious scholarly historical work, serious philosophical work, can make a very important contribution to the broader culture of the Left and to political activity as well.

I don’t think that it is useful or productive for people working in Marxist theory today to feel intimidated by some of the older divisions between an academic and an activist Marxism that emerged from the impasses encountered by the New Left. Theory also is a very important component of political practice, and theoretical practice has an important contribution to make to the broader culture of the Left, as one of our many “resources of hope.”

The Left needs places such as Historical Materialism and other journals to develop the theoretical tools which can then be taken up by all of us in different practices and political struggles.

GS: Another significant aspect of the Historical Materialism initiative is the conferences that it organizes which have a global character, considering that they are now held annually in four continents (India, Europe, Australia, USA/Canada). Would you like to comment on the origins of this and its transformation through time?

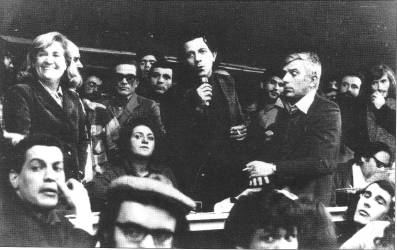

PT: The Historical Materialism Conferences started in 2004. We held the first conference here, at Birkbeck College in London. It was quite a small gathering, sixty or seventy people, and it involved the collaboration from the beginning with Socialist Register and the Deutscher Prize Committee. It was an attempt to draw together and to connect with some of the older traditions of Marxist theoretical publishing and a new generation.

We really moved decisively the next year, in 2005, to expand our international focus, particularly in Europe at that stage, and in increasing years we have been working hard to be in contact with comrades in Latin America, in South Asia, in South-East Asia, in North America and in many other parts of the world including Africa and the Arabic speaking countries. We have had success in building bridges with some cultures more than others, but we continue to try to reach new discussion partners.

It has been an intense process of expansion: the conference grows each year, there are more and more proposals for panels and for papers. This year we received well over two thousand proposals for papers, though we only had room to accommodate a very small number of these — around 300. International interest has been expanding for a number of years now, with conferences in other parts of the world, such as Toronto, New York, Sydney and Delhi. We are presently engaged in ongoing discussions about organizing conferences in Berlin, in Vienna, in Moscow, in Rome, in Athens and in Brazil.

I think that we can explain this international interest in terms of comrades working in other countries identifying the type of conferences we organize as Historical Materialism as a distinctive model of discussion and debate on the Left. We offer space for theoretical reflection and serious theoretical debate, we do not tolerate sectarian polemics, and we insist that comradely and civil standards of debate are respected, even when people have strong and passionate disagreements.

We are also keen to create a space of discussion in which theory and politics can organically grow together; but as the young Marx teaches us, that means not only that theory should go towards politics, but also that politics should come towards theory.

I would thus suggest that in some sense the Historical Materialism conferences represent a space for a political form of “theoretical practice,” to use an Althusserian phrase (and again, this characterization is one with which many of my fellow editorial board members, non- or anti-Althusserians, certainly will not agree!). I think that our attempt to build the Historical Materialism conferences as a distinctive space of theoretical reflection on the Left has been successful if we judge by the number of people who come to the conferences regularly year after year and have identified these conferences as important spaces for the development of their own work.

It has also been successful judging by the wide international interest in holding events similar to the Historical Materialism conference in many other countries, either in direct collaboration in the journal or as independent initiatives (the recent conference held in Paris, Penser l’émancipation, could be taken as an example of the latter model, inspired in some ways by Historical Materialism).

I think the combination of these elements indicates that Historical Materialism has played a small modest role of leadership in promoting new models of discussion and debate on the Left; but it also indicates that there was a readiness amongst the left and amongst Marxists around the world to work together towards finding these new forms of debate and discussion.

I think that one of the reasons for such an interest has also been the fact that the upturn in social struggles over the last decade has been accompanied by a renewed need for theoretical clarification and preparation for future struggles. The conjuncture has thus given rise to a sort of ‘fortuitous encounter’ between theory and practice.

GS: The conferences have succeeded at creating a new solid radical milieu around them. What else has HM accomplished?

PT: I think we have helped to create a space where there are ongoing discussions from one year to the next, which has led to the emergence of new and collective research projects out of Historical Materialism conferences. That has occurred not only in the sense of publications being produced, journal articles, edited collected volumes, and so forth, but also in terms of other conferences emerging from those workshops and seminars.

For a long period, in the 1980s and 1990s, the bridges of the international left collapsed and there was very little regular exchange between different national-theoretical cultures, with some important exceptions. We have attempted to create a space where there is more regular and ongoing contact between different cultures. The success of these efforts up to now is obviously only partially due to the efforts of the Historical Materialism editorial board; equally if not more important has been the enthusiasm with which people have responded to our initiatives, which is what has made them such a success.

Another distinctive feature of the conference of Historical Materialism this year in London was the fact that a lot of panels focused on discussions regarding the current feminist trends.

I think this is a fundamental and decisive development, and one towards which we have been working for very many years. We have been trying for over a decade to reinitiate the Marxist-feminist discussions which, for many difficult reasons, in some countries and some cultures on the Left internationally, had fallen apart after the upsurge of very interesting work in the 1960s and 1970s.

In some cultures, such as Germany, there was a continuing Marxist-feminist dialogue that was very productive, and continues today to produce important new work. In English-speaking world, for different reasons, there was a collapse of the important and integral contacts between important sections and Marxist and feminist theory.

Today, though, we are witnessing a new generation of young women — but also of queer theorists and people from other traditions — engaging with these questions and making an essential contribution to the new theoretical debates.

In my personal opinion, any future vibrant Marxist theory will necessary simultaneously be a socialist feminist-Marxist theory. We cannot develop Marxist theory without this central component, without theorizing one of the core areas of capitalist exploitation and oppression.

We are continuing to promote these discussions and debates and make them not simply one part or one disciplinary area of Marxist discussions, but absolutely fundamental to debates in all areas of Marxist theory. The response that we have received over the last years to these initiatives indicates that there is a lot of energy, particularly amongst younger socialist feminist theorists, to expand this project.

___________________________________________________________________________________

HM 2017 Conference (see here for more details)

Organised in collaboration with the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Committee and Socialist Register.

Plenary sessions

- Andreas Malm's Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Lecture 'In Wildness Is The Liberation Of The World: On Maroon Ecology And Partisan Nature' on Friday evening

- Panel on 'Value and Value Theory' with David Harvey, Michael Henrich and Moshe Postone on Saturday evening

- Closing plenary on 'Race, Migration and the Left' on Sunday evening

Streams

- The Great War, the Russian Revolution and Mass Rebellions 1916-1923

- Marxism, Sexuality and Political Economy: Looking Forwards, Looking Backwards

- Green Revolutions?

- Marxist-Feminist Stream

- Race and Capital

One hundred years ago, hailing the Russian Revolution, Antonio Gramsci characterised the Bolsheviks’ success as a "revolution against Capital." As against the interpretations of mechanical "Marxism," the Russian Revolution was the "crucial proof" that revolution need not be postponed until the "proper" historical developments had occurred.

2017 will witness both the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution and the 150th anniversary of the first publication of Marx’s Capital. Fittingly, the journal Historical Materialism will celebrate its own twentieth anniversary.

In his time, Gramsci qualified his title by arguing that his criticism was directed at those who use "the Master’s works to draw up a superficial interpretation, dictatorial statements which cannot be disputed," by contrast, he argues, the Bolsheviks "live out Marxist thought." From its inception, Historical Materialism has been committed to a project of collective research in critical Marxist theory which actively counters any mechanical application of Marxism qua doctrine. How the Russian Revolution was eventually lived out — with all of its aftershocks, reversals, counter-revolutions, and ultimate defeat — also calls not just for a work of memory but for one of theorisation.

We might view the alignment of these anniversaries, then, as disclosing the changing fates of the Marxist tradition and its continued attempt to analyse and transform the world. Especially once it is read against the grain of the mechanical and determinist image affixed to it by many of the official Marxisms of the 20th Century, and animated by the liberation movements that followed in its wake, the work-in-progress that was Capital seems vitally relevant to an understanding of the forces at work in our crisis-ridden present. The Russian Revolution, on the contrary, risks appearing as a museum-piece or lifeless talisman. By retrieving Gramsci’s provocation, we wish to unsettle the facile gesture that would praise Marxian theory all the better to bury Marxist politics.

Gramsci also remarks that Marx "predicted the predictable" but could not predict the particular leaps and bounds human society would take. Surveying today’s political landscape that seems especially true. Since 2008, we have witnessed a continuing crisis of capitalism, contradictory revolutionary upsurges — and brutal counterrevolutions — across the Middle East and North Africa and a resurgent ‘populist’ right represented by Trump, the right-wing elements of the Brexit campaign, the authoritarian turn in central Europe and populist right wing politics in France; the power of Putin's Russia and authoritarian state power in Turkey, Israel, Egypt and India. Even the "pink tide" of Latin America appears to be turning. Disturbingly, we seem to face a wave of reaction, and in some domains a recrudescence of fascism, much greater in scope and intensity than the revolutionary impetus that preceded and sometimes occasioned it. There is a new virulence to the politics of revanchist nationalism, ethno-racial supremacy, and aggressive patriarchy, but its articulation to the imperatives of capital accumulation or the politics of class remains a matter of much (necessary) debate.

This year’s Historical Materialism Conference seeks to use the "three anniversaries" as an opportunity to reflect on the history of the Marxist tradition and its continued relevance to our historical moment. We welcome papers which unpack the complex and under-appreciated legacies of Marx’s Capital and the Russian Revolution, exploring their global scope, their impact on the racial and gendered histories of capitalism and anti-capitalism, investigating their limits and sounding out their yet-untapped potentialities. We also wish to apply the lessons of these anniversaries to our current perilous state affairs: dissecting its political and economic dynamics and tracing its possible revolutionary potentials.

*****************************************

The HM conference is not a conventional academic conference but rather a space for discussion, debate and the launching of collective projects. We therefore discourage "cameo appearances" and encourage speakers to participate in the whole of the conference. We also strongly urge all speakers to take out personal subscriptions to the journal.

On Intellectuals

Deirdre O’Neill and Mike Wayne

This essay is taken from the forthcoming anthology Considering Class, Theory, Culture and the Media in the 21st Century, (eds) Deirdre O’Neill and Mike Wayne, Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2018.

Introduction

This essay explores the social and political role and significance of the intellectuals within capitalist society. It sets out to define the intellectual and the nature of what they produce (ideas) and their relationship to broader class relations. It shows how key Marxist thinkers provide the basis for a socio-economic understanding of the activities and products of the intellectual. At the heart of transforming the current role of the intellectual within the existing divisions of labour, lies the project to democratise the social role of the intellectuals. This requires expanding the social base of the intellectuals and connecting their activities to a self-reflexive project of social and political transformation. This is the basis and definition of truly critical thought. In this essay we discuss how Marx and Engels’ began the task of establishing a theoretical framework for a historical and materialist account of the intellectuals inThe German Ideology. We show how the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci further developed our understanding of the intellectual and we clarify and add to his key distinctions between the traditional and organic intellectual. Having set out the theoretical framework and broad philosophical and political implications of the intellectual, we then look at the role of the intellectual in the post-Second World War era, up to our contemporary moment. We discuss the relationship between the middle class and the hegemonic intellectual, the difficulties posed for the middle class intellectual to be genuinely counter-hegemonic and the need for the reconstitution of organic intellectuals from the working class. Finally we explore these issues in relation to the media and especially oppositional digital and social media practices.

Marx and Engels on the Intellectuals

The starting point for thinking about a Marxist conception of the role of intellectuals must be Marx and Engels’ work The German Ideology. It is here that they begin to situate intellectuals in relation to the dominant class forces. “The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production at its disposal ” (Marx and Engels 1989, 64). This formulation would grow in relevance with the development of the mass media. At the same time, the very growth of what Ensenzberger later called the ‘industrialisation of the mind’ (Ensenzberger 1982) would require the development of a sophisticated account of intellectual production that could avoid the twin traps of reducing it to the economic class interests of the dominant class who formally own the media or believing that it transcended class relations and struggle. Marx and Engels noted that “mental production” was delegated to the “thinkers of the class (its active, conceptive ideologists…)” (Marx and Engel 1989, 65). The beginnings of an account of intellectual production that could register how it may be affected by broader social, political and economic changes and conflicts is evident where they state that a “cleavage” between intellectuals and the dominant class “can develop into a certain opposition and hostility”, although they are also (overly) quick to state this conflict “automatically comes to nothing” if the dominant class to which the intellectuals are attached, are “endangered” (Marx and Engels 1989,65). Their own political trajectory suggests that this is not necessarily the case.

Marx and Engels no doubt had in mind in this section of The German Ideology the German intellectuals and philosophers from whose ranks they emerged in the 1840s and from whom they wished to establish an epistemological and political break.The German Ideology opens with a satirical account of the post-Hegelian scene, in which Left and Right Hegelians fought over the legacy and meaning of the master philosopher Hegel, who had died in 1831. In the minds of said protagonists, these philosophical battles were momentous, a “revolution beside which the French Revolution was child’s play” (Marx and Engels 1989, 39). Dissecting the moment, Marx and Engels lampoon the series of fashions and fads to which this intellectual production fell victim. In terms that seem strikingly relevant today, they pinpoint how commodification and competition erodes the authentic usefulness of ideas which suffer a gradual “deterioration in quality, adulteration of the raw materials, falsification of labels”, the results of which “is now being extolled and interpreted to us as a revolution of world significance, the begetter of the most prodigious results and achievements” (Marx and Engels 1989, 39-40). With only a little less of a sweeping dismissal, these words do seem more than a little pertinent to some of our own intellectual ‘revolutions’ in recent years.

The problem for Marx and Engel’s was that the Left Hegelian ‘revolutionary’ philosophy “never quitted the realm of philosophy” (Marx and Engels 1989, 40). As a result, methodologically it remained flawed in its ability to ground idea-systems in their real conditions of existence. “It has not occurred to these philosophers” Marx and Engels noted, “to inquire into the connection of German philosophy with German reality, the relation of their criticism to their own material surroundings” (Marx and Engels 1989, 41). It was this lack of self-reflexive interrogation that made German philosophy an ideology. Their own philosophy, historical materialism, would break with this lack of self-reflexivity and provide the basis for a socio-economic understanding of the activities of the intellectual. The intellectual and the most prestigious form of intellectual production, philosophy, could not, in their view, be seen as some free-floating, universal group transcending social conflicts. Ideas and the producers of those ideas had to be socially contextualised.

Along with this methodological break there was a political break to be made from the Left Hegelians. The intimations of change, the analysis of the need for change, the need to identify the forces of change and press them forward in a progressive direction, could not occur unless philosophy was integrated into those social forces and political action. As Marx famously put it in the Twelfth Thesis on Feuerbach: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point is tochange it” (Marx and Engels 1989, 123). In re-uniting philosophy with democratic social change Marx and Engels aim no less than to set in reverse the entire historical development of intellectual production and consciousness in class societies. This development has been marked by the division of labour between manual and intellectual labour and within the latter, the development of ever more specialised regions such as philosophy, ethics, theology, law, etc. (Marx and Engels 1989, 51-2).

The basis of a democratic conception of the intellectual is at least sketched out in this early work. Since consciousness for Marx and Engels develops out of our everyday practical productive life, satisfaction of needs and the production of new needs and the co-operation this requires, then an explicit and self-conscious reconnection of intellectual functions to the social production of life would seem both possible and desirable. Habermas argued that by “turning the construction of the manifestation of consciousness into an encoded representation of the self-production of the species, Marx discloses the mechanism of progress in the experience of reflection…” (Habermas 1978, 43). Yet Habermas warned that this was vitiated by the fact that self-reflection was reduced to and made identical with labour. In so doing Marx “reduces the process of reflection to the level of instrumental action” (Habermas 1978, 44). If this were the case then Marx would be no more than a philosopher of the factory, as it were. But Marx neither saw labour in such instrumental terms (he saw it as intrinsically creative even if tasked with meeting certain historical needs) nor saw the intellectual and creative functions as having their highest manifestation necessarily within the material production of the species. Marx’s philosophy is perfectly capable of sustaining the view that our intellectual activities find their highest culmination in culture, communication and aesthetics, where some distanciation from immediate needs have been established (Wayne 2016, 140-48). Historical materialism is not reductionist in relation to consciousness and its specialised manifestations, it merely poses the crucial question: what are the methodological and political-moral implications of the idea that intellectual activity has certain conditions of existence that involve the totality of society?

The question of the actual and desirable relationship between the intellectual and other forms of labour is significant primarily because it is capitalism that has the instrumental view of labour (which Habermas uncritically accepts in its impoverished form as inevitable). Furthermore, today it is capitalism that poses a clear and present danger in reducing intellectual activity to serving the needs of the labour process, subordinate as it is to capital, and thus eliminating the critical component of reflective thought. In order to realise that critical component Marx and Engels recommended articulating thought to those social agents struggling for progressive change. The internal conflicts within the ‘conceptive ideologists’ of the dominant class (the fight between the Right and Left Hegelians) were not insignificant. It helped expand the repertoire of discourses available and seed the ideas for change. However, for these seeds of change to be activated required intellectuals to break both methodologically and politically with the dominant class. This is what Marx and Engels did in fact do.

Gramsci on the Intellectuals

The Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) has widely and rightly been seen as making a significant contribution to the Marxist understanding of the role of intellectuals. Like Marx and Engels he argued for a democratic conception of intellectual activity. Taking the most prestigious form of intellectual production, philosophy, as an example, he argued that “all men [sic] are “philosophers”’ insofar as everyone has a specific conception of the world, a “worldview” which they have forged out of their experience and circumstance. The task was to develop philosophy, both in its specialised form as scholarship and in its everyday form, into “critical awareness” (Gramsci 1967, 58). As we have seen, for Marx and Engels, the philosophy of the intellectuals would develop its critical potential the more it could interrogate its conditions of existence. With a slight nuancing, the same prescription was applied to the philosophy of everyday life. Gramsci argued that it needed to develop critical awareness by a) not accepting ideas and value-systems passively from the dominant institutions in society and b) overcoming its fragmented and disparate character and developing itself as a systematic and coherent worldview in the way traditional philosophers have had the time to do with their own more ‘rarefied’ systems. The ideal of developing a popular form of critical philosophy would have to overcome and address a number of problems concerning the actual historical development of intellectual production and its relationship to powerful socio-economic groups. It would have to overcome firstly the fact that “All men [sic] are intellectuals…but not all men have in society the function of intellectuals” (Gramsci 1998, 9). This is the division between intellectual and manual labour. Secondly, within the ‘function of intellectuals’ there are different types of intellectuals.

Gramsci identified two types of intellectuals. The first were what he called the traditional intellectuals, which he defined rather ambiguously in both historical terms and social-ideological terms. The historical definition of traditional intellectuals refers to the way intellectuals associated with one mode of production need to be assimilated by the intellectuals associated with a rising class and a new mode of production. So that for example, the intellectuals of the feudal mode of production (clerics, scholars, artists) had to be integrated and re-functioned according to the new practices and needs of the capitalist mode of production (Gramsci 1998, 10-11). Likewise, the intellectuals developed within capitalism would become the ‘traditional’ intellectuals vis-à-vis the development of a socialist mode of production, and again would need to be assimilated into new social priorities and needs. Gramsci also defined traditional intellectuals as those within the capitalist mode of production that remained remote and aloof from the economic and political needs of the capitalist class despite their assimilation. Again clerics and philosophers and perhaps much of the arts and humanities within the academy might once have fallen within this type of intellectual function, where non-instrumental metaphysical values could be articulated. These intellectuals are ‘traditional’ when compared to Gramsci’s other main category: organic intellectuals.

To understand the concept of organic intellectuals, we have to first relate this concept to two other concepts in Gramsci’s work: the economic-corporative and hegemony. Gramsci argues that the political consciousness of a dominant class is one which must move beyond merely a defence of its own economic interests. It must move firstly to unite with other fractions of its own class, in the way that different kinds of capital, such as industrial, financial, commercial and landed capital have historically done. If a class stays at just this level of defending its economic interests, it stays at the level of the economic-corporative. Beyond establishing intra-class cohesion a dominant class must move beyond their own collective interests and command the moral-political terrain across society, so as to convince all other classes that their interests can be met by aligning themselves with or accepting the rule of the dominant class. When a dominant class achieves this, it is not merely dominant but also hegemonic (Gramsci 1988, 205-6). By hegemonic, Gramsci means that this is a class that wins (at least to some degree) the consent of the exploited classes to their situation.

It is the role of the organic intellectuals to produce this consent and to do so they work primarily to change and influence culture, morality and political agendas. Classically, organic intellectuals would have been found in political parties, in the top most prestigious newspapers, in public relations and advertising and perhaps today also in think tanks. These intellectuals are tied organically to the economic and political needs of the dominant class. In recent times, these are the thinkers, commentators, editors, writers, broadcasters and so forth that try and persuade the general population that neo-liberalism means progressive reform.

However, Gramsci also refers to the practical organisers of production, the scientist and the engineer for example, and today also we would say managers, as intellectuals. We might think that the organic intellectual would automatically include these kinds of intellectuals organised at the heart of the production process. But this interpretation is at odds with Gramsci’s analysis of the economic-corporate activity of the dominant classes and the need to go beyond their immediate economic needs and build political alliances and broader political-moral projects (such as neo-liberalism). A number of writers have suggested that with the expansion of corporate and state bureaucracies, the economic-corporate role of the intellectual, working within and primarily concerned with the needs of the state or the company, has expanded (Boggs 1993, and see Pratschke in this volume). This has led to the expansion and redefinition of intellectual functions that are neither ‘traditional’ because they are so obviously tied to the dynamic and moving terrain of occupations responding to economic forces, nor are they ‘organic’ in the sense that their agenda is more focused on the smooth functioning of an apparatus rather than the broader project of public persuasion and politics. We need then to supplement Gramsci’s analysis with a new category, that of the technocratic intellectual. This is the ‘expert’ in science, engineering, law, economics, management, even the trade union leader and negotiator, etc. They embody specialised and instrumentalised forms of knowledge. They work within the framework of policy, which ultimately stems from the broader political struggle conducted on the terrain of the masses and the organic intellectuals. They administer but do not determine, they examine how things work but not why things work as they do, and within that framework they may produce new solutions, products and ideas. If they become great advocates of such new ideas and practices that re-shape how we look at the world more broadly, from Henry Ford to Steve Jobs, then they lift themselves out from the merely technocratic intellectual onto the terrain of the organic intellectual. The technocratic intellectual, long dominant in the natural and social sciences, has been in the last few decades, reshaping the humanities and arts as well as the critical social sciences. Edward Said argues that the greatest threat to independent intellectual thought comes from the dominance of this technocratic type of intellectual. For Said:

The major choice faced by the intellectual is whether to be allied with the stability of the victors and rulers or – the more difficult path – to consider that stability as a state of emergency threatening the less fortunate (Said 1996, 35).

We can now tabulate the different types of intellectual functions we have discussed:

1. Traditional: either eclipsed by the new rising class and/or the economically and politically marginalised intellectuals within capitalism.

2. Technocratic: numerically the biggest class of contemporary intellectual activity, working within economic-corporative horizons.

3. Organic Intellectuals. They are defined not by their occupation but by the scope and compass of the change they seek to initiate.

This category can be subdivided between:

i) Hegemonic organic intellectuals who work on behalf of the capitalist class and whose main business is in helping to shape the broader political-moral, social and cultural agenda.

ii) Counter-Hegemonic organic intellectuals. They work to call the dominant frames of reference, the dominant assumptions, and the dominant policy trends that favour capitalism, into question. They are organically tied to the classes and groups for whom stability is ‘a state of emergency’. This group can in turn be sub-divided between:

ii. a) those that, like Marx and Engels, come from the middle classes but who have distanced themselves from the hegemonic group politically, psychologically and ideally, in terms of their practices (but often they fall short of this crucial need to democratise their practices, retaining instead the stamp of elitism);

ii. b) those intellectuals that develop from within the working classes and other subaltern groups (but who must resist assimilation and neutralisation within the established institutions).

Organic Intellectuals Today

In his 1967 essay on the role of the intellectual in Western democracies Chomsky considered the intellectual in relation to the concepts of responsibility, power and truth seeking. He argued that their relative power bestows upon them a responsibility to interrogate, critique and expose the disastrous effects of right wing ideologies.

Intellectuals are in a position to expose the lies of governments, to analyse actions according to their causes and motives and often hidden intentions. In the Western world, at least, they have the power that comes from political liberty, from access to information and freedom of expression. For a privileged minority, Western democracy provides the leisure, the facilities, and the training to seek the truth lying hidden behind the veil of distortion and misrepresentation, ideology and class interest, through which the events of current history are presented to us (Chomsky 1967)

There are two significant contextual points to be made here. Firstly Chomsky was writing in relation to the Vietnam War over fifty years ago. It was a challenge to the intellectuals of the time to expose the lies that were disseminated in order to justify a war that killed over a million people in total. Secondly he is referring here to a particular kind of intellectual, that is the counter hegemonic intellectual. As we have pointed out in the discussion of Gramsci, we can consider the role of intellectuals in two ways as hegemonic or as counter hegemonic. While the type of intellectual Chomsky refers to is one that works to expose the facade of the powerful there are intellectuals who can just as easily play a role in reinforcing the status quo. The Vietnam War as with the Iraq War in 2003 had its intellectual cheerleaders, giving power the gloss of higher ideals (the 2003 war was we were told about defending and extending freedom, democracy, etc.).

Conventionally those who are considered to be intellectuals –or we could call them professional thinkers -have hailed from the upper and middle classes. This is not because these groups possess an inherent intelligence consistently absent from the working class. Rather it is because those from the middle and upper class designated as intellectuals -or as Gramsci would have it fulfilling the function of the intellectual- are in possession of the social, cultural and economic capital that makes such a designation possible and ensures they are recognised and acknowledged as such by other members of their class. This means it is possible to understand the hegemonic intellectual not in relation to a superior ‘intellect’ (whatever that might mean) but in terms of their significant role in the reproduction of the socio -economic relations of capital.

It remains true today that the majority of contemporary hegemonic organic intellectuals in the UK are drawn from the middle and upper classes. The decision-making professions within which many institutional intellectuals operate are dominated by privately educated Oxbridge graduates who posses a shared culture, value system and set of attitudes which when taken together coalesce into a world view which they hold in common. The link between education and the production of intellectuals has meant that formal education has been a crucial filter by which to reproduce an intellectual class dedicated to reproducing the class system (Reay 2010, 400). It is within the private education system and the universities of Oxford and Cambridge that the middle and upper class intellectuals learn about the way in which the world works. Here they are prepared to run that world as if opposition to their view of the world is a deviance from the norm.

What this means in effect is that as members of a middle class elite whose perspective is universalised, intellectual engagement with the condition of society and the way in which it is organised and regulated is filtered through the sensibilities of those for whom the prevailing structural arrangements do not appear to be alienating and exploitative. Whilst there is no suggestion that the hegemonic intellectual is unable to engage critically with the world –indeed they even, at times, are able to appear radical- the depth of their analysis and level of critical engagement is typically limited because the position they inhabit is a privileged one. Consequently their radicalism only appears as such when presented to other hegemonic intellectuals. Significantly their intellectual endeavour evaluates the immediate situation and typically accepts the given parameters in place to make sense of that situation while a more critical intellect “evaluates evaluations” (Hofstadter 1966, 25). As Schwartz has pointed out many university students are aware of the reason that corporate boardrooms should promote diversity “but few question the concept of corporate rule itself” (2013,184) .

If the role of the critical intellectual as Chomsky claims is to make public what the powerful would rather keep hidden, we need to recognise the significance of this in relation to a contemporary society consistently divided along class lines and to realise any intellectual endeavour wishing to ‘evaluate the evaluation’ must eventually engage with the question of class and the unequal distribution of economic and cultural resources which class divisions rest upon. It is the approach to this question we would argue that separates the hegemonic and counter-hegemonic intellectual. As Marx made clear it is only by engaging with the question of class, the ways in which class is structured and reconfigured over time, that we can begin to understand the nature of capitalism and come to terms with his claim: “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles” (Marx 1985, 79).

The crucial point here is that for the hegemonic middle class intellectual, class is not an overtly exploitative or antagonistic relationship. Their experiential horizons are confined by lives of privilege where the politics of identity takes a primary position. The last thirty years of neoliberalism has witnessed class as a source of intellectual analysis take second place to the politics of race, sexuality and gender, concepts that affect the middle class the most. In the meantime economic inequality has increased to historically high levels, the working class have been incrementally excluded from the public sphere and immigrants forced to live and work in the most appalling conditions. Yet those in positions of intellectual power have normalised and universalised this inequality.M While their own class world becomes normalised questions of class, which are essential to any transformative process, are secondary. This has allowed for an on-going abdication of any responsibility towards the working class and no demand for a critical self-interrogation necessary to consider the role class plays in the social relations of exploitation. As Marx has made clear, it is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social being that determines consciousness (Marx 1977, 181). While it is possible, through social change and political events (e.g. war, political revolutions, etc.) for consciousness to be reconfigured and established dominant patterns of social conditioning that has formerly shaped a life to be questioned, the tendency is for social being to produce the consciousness that is most conducive for the reproduction (within a range) of the social relationships in which social being is formed.

The problem then becomes one of praxis; of intellectual work that is able to inquire into and evaluate the connection between ideas and their material affects and translate them into new ways of being as Marx and Engels called for in The German Ideology. The process of re-evaluating ideas about the world can bring about the potential to transform the world. Thus conservatives and liberals are certainly not averse to acknowledging that inequality exists, but they never come up with policy ideas that could remotely change this situation. When they are confronted with policy ideas that could have a positive impact on inequality, they attack those ideas as ‘extreme’ because they encroach, necessarily on the prerogatives of private property. Gramsci linked the economic rule of the elites to the complex practices of everyday existence where to a great extent there is an unquestioned conformity to the rules and conventions of a given social order. This intellectual acceptance of hegemonic boundaries, this refusal to surmount the imposed limitations of the institutions, politics and ideological framework of neoliberalism, illuminates the distinction to be made between the hegemonic and counter-hegemonic intellectual.

Non-conformity to these rules, a refusal to live by their precepts, engenders in the counter-hegemonic intellectual the condition of potential isolation and marginalisation and indicates an acknowledgement that analysis is informed by and dependent upon action – and vice versa. At present the hegemonic power of the dominating groups is such that the critical analysis required for strategic explorations of the consequences of objective material structures exists in isolation from the action required to transform society.

This is no more apparent than in the claim associated with the Occupy movement that began in the US: ‘we are the 99%’. This slogan functioned to differentiate the majority from the obscenely rich capitalist class minority right at the top of society. We would argue that this contradictory model of inclusivity is problematic and functions to exclude the working class by smoothing out the differences in lives that are significantly different within the majority. On the one hand the slogan draws attention to a powerful global elite at the top of society who exist in a shadowy world of financial deals and political agreements. At the same time it eradicates the peculiarities, oppressions and exploitative relationships of many members of the working class and the very real class differences and conflicts that exist between groups within the 99%. This collapsing of the working classes and the more privileged lives of the confortable middle class into one homogenous mass inevitably functions to exclude the working class from the struggle for change and leads to a weakening of the potential to build intellectual and political arguments and crucially, anti capitalist alliances that acknowledge the material realities of working class life. As a ‘unifying’ slogan it is unable to engage with the complexities of a classed stratified, multi ethnic globalised world. What is envisaged, as a tool against neoliberalism becomes in effect a method of annihilation – a theoretical and essentialising meme which both conceptually and practically results in the destruction of the working class as a category. Similarly, orthodox Marxist conceptions which equate ‘the working class’ with wage-labour are problematic, since they disavow the different types and levels of cultural, social and economic advantage the middle class wage-labourer has, as well as their position of administrative, managerial or intellectual dominance over other strata within the category of ‘working class’.

This returns us to the concept of praxis and its relationship to working class intellectuals. What it demonstrates is the need for the middle class intellectual to adequately address their relationship to existing structures and patterns of inequality in which they are implicated and their increasing control of the means of communication, their domination of the media, academia and other decision making professions, all of which are conduits for the transmission of power and the construction of ideology (Wayne and O’Neill 2013). The truly counter-hegemonic middle class intellectual who seeks an organic relation to the working class must remember that, as Marx wrote in ‘The Theses on Feuerbach’, “it is essential to educate the educator” (Marx and Engels 1989,121). A dialectical relationship of mutual learning means that organic intellectuals must also emerge from within the working class.

The counter-hegemonic working class intellectual traditionally was dependent on organisations and institutions such as trade unions, adult education institutions and socialist parties (Rose 2001) to provide the means to develop as counter-hegemonic thinkers. Yet neoliberalism has progressively destroyed or neutralised these organisations. It is a political truism to claim neoliberalism is responsible for the rolling back of the welfare state and the destruction of the public services that function within it. One of the consequences of this is a shrinking of the public sphere and the access to it that is essential to making subaltern voices heard (Wacquant 2008).

Neoliberalism has destroyed the fabric of the communities in which the working class found material and ideological strength and in the process strategically depoliticised the working class. The left intelligentsia has receded into a kind of “ideological policing” (Hall 2012, 9) obsessed with theories of differences and transgression that has resulted in its increasing insignificance and the erosion of the concept (and practice) of social solidarity. Schwartz reinforces this point in his discussion of radical theory:

As the right’s growing hegemony from the 1980s onwards eroded majoritarian support for progressive taxation and universal public goods, radical theory, through its dominant concerns for difference and transgression, abandoned any intellectual defence of the core democratic value of social democracy (Schwartz 2013, 395).

The destruction of the civil society in which the working class had established some organisational and institutional bases, has also eroded the links between the working class and the middle class. Middle class intellectuals could once be rooted in working class struggles such as trade union movements, social movements (such as Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners) or in the colleges and working-men’s institutes, civil rights protests, and so forth. As all of these have become weakened, so the role of the counter-hegemonic radical intellectual has declined. Our reading of this situation leads us to suggest that the middle class counter-hegemonic intellectual requires movements and working class intellectuals to work along side and to learn form. A symbolic moment when the working class counter-hegemonic intellectual and the institutional production of middle class intellectuals converged, was Jimmy Reid’s 1972 inaugural address as Rector of Glasgow University. Reid was a leading figure in the 1971 work-in to save the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders from bankruptcy. In Britain now it is virtually unthinkable for a University to appoint a radical trade union leader to such a position and to acknowledge that the ‘educators need educating’. Ours in not the era to give such a platform, such a vindication and such an acknowledgement, to a radical organic intellectual of the working class. In his famous address Reid made a direct appeal to the students as intellectuals in the making:

A rat race is for rats. We're not rats. We're human beings. Reject the insidious pressures in society that would blunt your critical faculties to all that is happening around you, that would caution silence in the face of injustice lest you jeopardise your chances of promotion and self-advancement. This is how it starts, and before you know where you are, you're a fully paid-up member of the rat-pack (Reid 2010).

Yet if the old established platforms (the universities, the press) have become integrated into the neoliberal order and hostile to participation of the working class as critical thinkers, new spaces have opened up around the digital media.

Counter-Hegemonic Spaces and the Digital Media

In our multi-media saturated society the significance of the media as a site of hegemonic and counter-hegemonic struggle takes on a dynamic role in framing our social and historical experiences and the ways in which they are interpreted, evaluated and made sense of. Within the dominant media environment, the processes of public debate, policy-making and political power are asymmetrically skewed towards both the middle classes and large capital interests. The dominant media are run by middle class intellectuals who largely operate within the spectrum of liberal and conservative thought and opinion in the current period. In the UK, the leading editorial thinkers on the premier liberal paper The Guardian have overwhelmingly been privately educated and went through Oxford or Cambridge. They police the boundaries of the acceptable and at their more ‘radical’ end of the spectrum they present as counter-hegemonic intellectuals and ‘left-wing firebrands’. The ideological effect of incorporating ‘radical’ politics inside such dominant organs is that anything outside those boundaries can be labelled and dismissed as ‘extremist’.

One example of the policing of who gets to speak, where and on what issues is Russell Brand. Brand crossed boundaries that unsettled the established hierarchies and divisions of labour. Here was an ‘entertainer’ who became politicised and began commenting critically on political matters. But he was also from a working class background that was outside the golden Oxbridge circle and this seemed for many liberals to disqualify him to speak on political issues and be a political actor (See Fisher 2013, El-Gingihy 2014 and for an example of the established political commentators’ collective noses being firmly put out of joint, O’Hagan 2014). 1 In particular his critique of the current state of representative democracy in the UK and its inability to bring about progressive change (through voting) enraged many in the political and media class who are invested in the status quo. Brand disrupted the middle class norms of style in the way he talked (the accent and content), the way he dressed, his very tactile interactions with interviewers, etc., all spoke to an informal unpredictability that was seen as a symbolic attack on ‘serious discourse’. Brand launched his Trews news channel on You Tube which has more than one million subscribers and which regularly makes the media itself and their questionable shaping of the public agenda, his topic. 2 The development and popularisation of such media literacy is an important component of the oppositional digital and social media world, which defines its identity precisely in terms of its difference from the dominant media. The dominant media in turn fear this growing media literacy and meta-commentary on its practices since it calls them to account and deconstructs the naturalisation of the dominant media’s perspectives. The success of Brand’s Trews channel demonstrates that the digital and social media also threaten the dominant media in terms of audience reach and not just ideological critique.

Social media and digital media may also be seen as a counter-hegemonic model of labour or intellectual production. In contrast to those that have a corporate contract, bloggers, micro-bloggers, commentators, memes, online papers, You Tube political rappers such as bin-man Sean Donnelly (NXTGen) and so on, produce material in their spare time and in most cases for free. 3 The demographic background of the politicised social media are far more diverse than the narrow private school/Oxbridge nexus that filters and shapes the formation of British intellectuals. Although social media is often criticised for encouraging a privatised and individualistic politics (the so-called ‘keyboard activist’), we would argue that it can be a perfect example of praxis. Social media offers a means of offering clear and succinct explanations of what is happening and why it is happening; it provides the ‘theory’ in a idiom that is accessible to non-academics, and that can seed political action.

The digital and social media help produce horizontal communication that is very important in helping people overcome the sense of isolation and marginalisation that one feels when they have political views and opinions that find little or no place in the dominant media. In such a situation of tacit censorship it is easy to believe that few people share those beliefs and opinions, and this can lead to a demoralising atomisation of the left. Since many of the public spaces where working class people used to congregate have been decimated, virtual networks in the social media have provided one forum to reconstitute such opportunities for conversation and knowledge exchange. As with any other form of media, the social and digital media can be used for a variety of purposes, including highly reactionary ones. But the left has often shown itself to be suspicious of social and digital media as a mode of political engagement and this has meant underestimating its potentialities, or concentrating exclusively (in a reaction to the techno-determinists and techno-utopians) on the way the political economy of the internet for example is dominated by corporations (Dean 2009).

Gramsci’s argument that everyone is an intellectual but that only some people have the social function of being intellectuals is relevant here. We are arguing that the digital and social media enormously expands the range of people who can assume the social function of being an intellectual. The genre of citizen journalism has been enriched by an influx of counter-hegemonic intellectuals who do not respect the narrow norms and rules of political discourse. To take one random example, Rachel Swindon has been micro-blogging on her Twitter account exposing Conservative MPs who voted to cut benefits while spending thousands of pounds of public money on their expenses claims. Interestingly this was a story in the dominant media back in 2009. But what Swindon has done is firstly pursue the story consistently over time, demonstrating that little has changed, whereas the dominant media tend to move on and have largely left the issue behind. Secondly, she has linked the on-going issue of MP’s expenses to the brutal cuts in benefits under austerity politics. By contrast the dominant news media keep such issues separate, thus failing to make the connections that reveal the class dynamics of the social totality. On the back of this successful campaign (she has more than forty-four thousand Twitter followers at the time of writing) Swindon has launched a blog declaring that the British media are failing to hold the Conservative government to account. Subscription models from readers/supporters often provide some financial support for this kind of citizen journalism.

Conclusion

Praxis is the integration of theoretical activities that have been cut off from the widest possible social base and restricted to elite demographics and narrow circles of action and knowledge. This is why Marx, Engels and Gramsci called for philosophy, the most elite but also most highly developed system of thought, to be brought back into contact with not ‘reality’ (since philosophy is hardly unreal) but the reality of the lives of the majority. Education – in the broadest sense and not just in formal institutions – is therefore a crucial part of developing praxis. Praxis means not only linking theory and practice, as it is typically defined, but democratising who gets to have access to those frameworks, perspectives and intellectual resources that provide the basis of critical thought and critical action.

The system-integrated intellectuals take different forms: the traditional intellectuals, remote from the immediate political or economic needs of capitalism, have always been on hand to provide spiritual, artistic, philosophical or other ideals that have provided important resources for the bourgeoisie in the ideological struggle. The organic intellectuals – those elites within the intellectual elite - who link the economic interests of the capitalist class with the broader strategic political and cultural goals of the class, fight the ideological struggle in the more immediate, day-to-day battle over the direction of social life. The massed ranks of the technocratic intellectuals follow their lead in the myriad institutions of modern society. It is from this dense bloc of integration that the middle class counter-hegemonic intellectual must emerge. Radical social change will need the critical leverage and resources within existing public opinion formation which intellectuals from the middle class already have. The contradiction between their access to the most sophisticated intellectual culture and the absurdity and irrationality of capitalism has often thrown them into conflict with it. But counter-posing rationality against the evident waste and crisis tendencies of capitalism does not break down the privileged superiority of the intellectuals.