Nathaniel Mills: Ragged Revolutionaries

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/revolutionnaires-en-haillons-entretien-avec-nathaniel-mills/

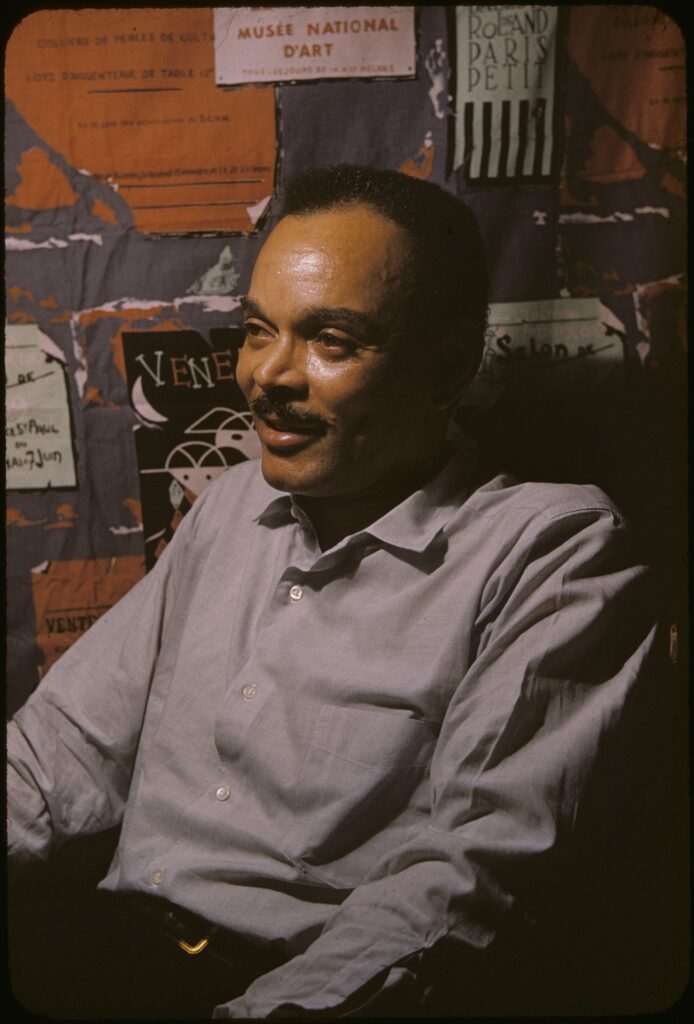

- In your book – Ragged Revolutionaries (University of Massachusetts Press, 2017) – you look at how African American authors (and especially members of the Communist Party of the USA, or close to it) have rethought the concept of theLumpenproletariat in “order to better explicate the socioeconomic and cultural structures of the modern United States” (p. 3). The fact that the concept ofLumpenproletariat is rather negatively-worded in “classical” Marxism and that African American leftists have reconceptualise it is a very interesting point, but why did you focus on authors and on literature? And why especially during the Depression-Era?

Catherine Bergin: Communism and Experiences of Race

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/chester-himes-ralph-ellison-richard-wright-communisme-et-experiences-vecues-de-la-race-un-entretien-avec-catherine-bergin/

- In the introduction of the book you have edited, African American Anti-Colonial Thought, 1917-1937, you write that one of the reasons why you choose to focus on this specific period is because “[t]his historical period also saw a novel relationship between African American activists and the Left in the USA, a relationship that strongly informed the race politics of the time” (p. 2). Could you please explain this point?

Kylie Jarrett: Feminism, labour and digital media

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/des-salaires-pour-facebooker-du-feminisme-a-la-cyber-exploitation-entretien-avec-kylie-jarrett/

- You recently published Feminism, labour and digital media : the digital housewife[1], in which you tried to frame the booming empirical research about digital technologies on the ground of post-operaist marxism and digital labour theories on the one hand, and of feminism on the other. What is decisive in the contribution of the first two ? Why should we put political economy, and even more specifically the concept of labour, at the core of our understanding of digital mediations?

Christian Fuchs: Internet and Class Struggle

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/internet-et-lutte-des-classes/

- Your book Digital Labour and Karl Marx offers an inspiring analysis of things we daily do, such as browsing on the internet, using social media... What motivated you to develop a Marxist theory of communication?

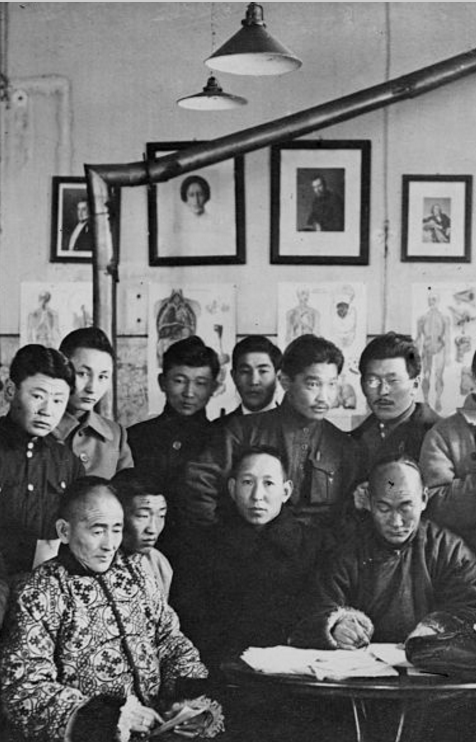

John Sexton: The Congress of the Toilers of the Far East

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/le-congres-des-travailleurs-dextreme-orient-entretien-avec-john-sexton/

- Could you please tell us about the origins of the Congress of the Toilers of the Far East (1922)? Why was this Congress much smaller than the Baku Congress (1920)? How can one explain that there were around 37 Nationalities in Baku but that the majority of the delegates during the Congress of the Toilers of the Far East came only from four countries (China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia)?

Stefan Kipfer: Gramsci as geographer

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/gramsci-geographe-entretien-avec-stefan-kipfer/

- Your research interests include a recurrent focus on space, specifically urban questions as well as the spatial organization of relations of exploitation and domination. Theoretically, you mobilize the works of Henri Lefebvre and Frantz Fanon, but you are also interested in Gramsci’s take on, for example, urbanity and rurality. How do you see the relevance of Gramsci’s analyses for geographical concerns today?

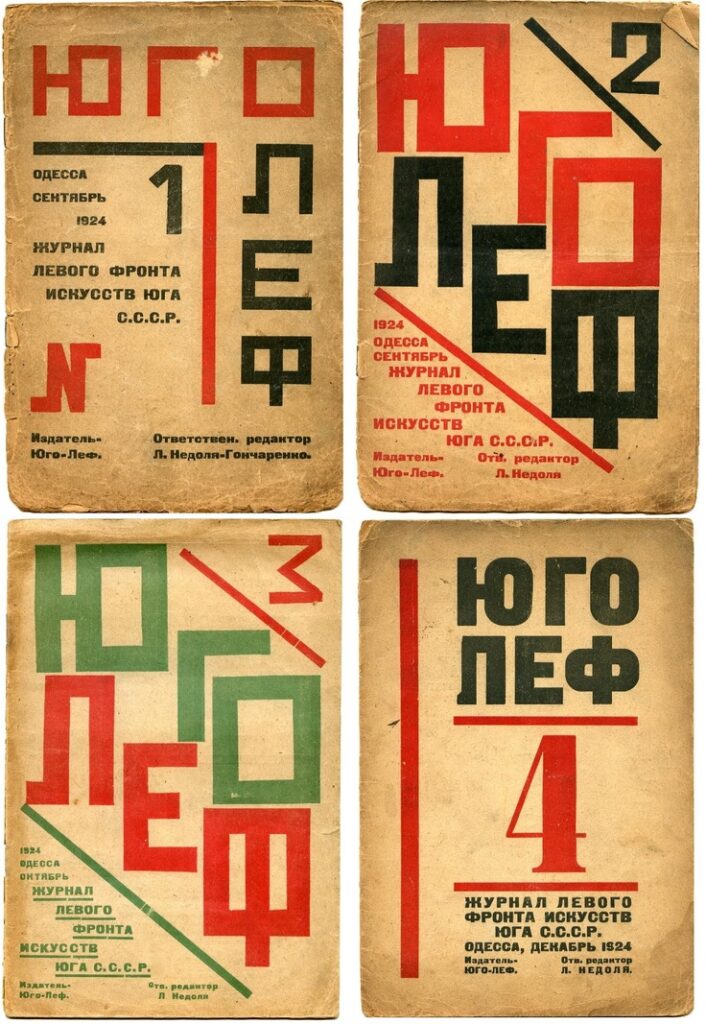

Craig Brandist: Language, Culture and Politics in Revolutionary Russia

A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/langage-culture-et-politique-en-russie-revolutionnaire-entretien-avec-craig-brandist/

Craig Brandist is Professor of Cultural Theory and Intellectual History, and Director of the Bakhtin Centre at the University of Sheffield, UK. Specialising in early Soviet thought, his books include Carnival Culture and the Soviet Modernist Novel (1996),The Bakhtin Circle: Philosophy, Culture and Politics (2002) andPolitics and the Theory of Language in the USSR 1917-1938 (with Katya Chown, 2010). Building on the research for his recent bookDimensions of Hegemony: Language, Culture and Politics in Revolutionary Russia (2015), he is currently working with Peter Thomas on a book about Antonio Gramsci's time in the USSR, and on early Soviet oriental studies.

- Could you please expand on the evolution of orientology that emerged at St. Petersburg University at the end of the 1890s and how « ideas [from those orientalists] about empire tended to coalesce around a liberal-imperial perspective » (p. 56)? To what extent did linguistics became an «autonomous discipline » with the 1917 Revolution?

Six points on the eve of the UCU strike

HM editorial board members are currently on strike in their pre-1992 UK universities over the private financialisation of pensions.

Editor Jamie Woodcock is an academic worker with a few institutions at present, some of which will be on strike starting the 22nd February 2018. He is a member of two trade unions: UCU and theIWGB. The following six points are intended as a brief reflection before the strike [this post was originally published byNotes From Below on 21 February 2018]:

1. The strike is about pensions!

The UCU is planning 14 days of strike action to oppose changes to the USS (Universities Superannuation Scheme) pension. For many workers, pensions are now limited to the legal requirement from employers. Others are denied pensions by using bogus self-employment status. At present, academic workers have a relatively good pension scheme.

There are two points worth noting about this pension scheme. First, while employers pay into the scheme, so do we. Second, the pension scheme has already partly been sold out. This means that early career academic workers already get a worse deal in USS. Instead of their pension being based on their final salary at retirement (which would mean more) it is now based on their career average (which would be less). Furthermore, academic workers in post-92 institutions are on a different pension scheme.

The changes are being forced through by Universities UK and supported by the Chair of the USS Board. They claim that the pension scheme is running at a deficit. Their valuation has been challenged and is based on a worst case scenario of all universities going bust at the same time. Their proposal is to move away from a “defined benefit” scheme, in which you can predict what your pension will be worth at retirement. Instead it will become a “defined contribution” scheme. Rather than a guaranteed amount, it means contributions are placed into an individual portfolio of stocks and shares, exposing them to risk. This means the benefit could reduce as the investment is gambled.

So, why should other people care about this? Public sector pensions not some sort of “privilege”, they are deferred earnings. Attacking these pensions has the potential to undermine private sector pensions too. While we are defending our pensions, they are something that all workers should receive. Within universities, reducing the cost of pensions opens up the possibility of further privatisation. Lower costs make universities a more attractive opportunity for private ownership.

2. The strike is not about pensions!

Universities have changed. When I finished my PhD, a professor of employment relations asked me where I would be taking up my lectureship. At the time I was working at three different universities in London, stringing together short term, hourly paid contracts. I had to explain – to a professor of employment relations – that work had changed for many in the university.

Over 50% of academic workers are now employed on precarious contracts. For example, many contracts are for only one year (sometimes excluding the summer). These can be extended, but not beyond three years. This is because the offer of a fourth year provides some scant employment protection.

Conditions are getting worse. There has not been an above inflation pay rise in universities since 2009. (As a side note, this was during my undergraduate degree. This means that during my entire time in Higher Education, the pay of academics has declined). Estimates put this loss in pay at 14.5% in real terms.

As we have written about elsewhere in Notes from Below, workers’ inquiry can be used to investigate and organise in the university. There is a long list of other issues including: precarity, pay (and the gender pay gap), institutional sexism and racism, workload modelling that bears little if any relationship to reality, stress and bullying, the pointlessness of REF (a way of comparing research outputs) and TEF (the teaching version), the attempt to make academics act like border officials, racist policies like Prevent, and so on.

Legally, this strike is about pensions, but it is also clearly about so much more. It is about all the other issues we know are happening at universities, but have not fought over. This is because we were told the big fight over pensions was coming.

For many, the strikes are about so much more than pensions. This is despite the fact that UCU is not officially contesting anything else.

3. We need to do the 14 days of strike action!

The UCU balloted members in 61 Universities and laid out a plan of strike action starting on the 22nd of February. The schedule is as follows:

First week: strike on Thursday 22nd and Friday 23rd of February

Second week: Monday 26th, Tuesday 27th, and Wednesday 28th of February

Third week: Monday 5th, Tuesday 6th, Wednesday 7th, and Thursday 8th of March

Fourth week: Monday 12th, Tuesday 13th, Wednesday 14th, Thursday 15th, and Friday 16th of March

The strike, withdrawing our labour, remains a key way we can fight our employers. This is also being accompanied by something called action short of a strike (ASOS). This involves working to contract, refusing to take on voluntary duties, etc. At some universities, there is now a threat that failure to do all of this additional work (outside of the contract) will result in full deduction of pay. This reveals how much unpaid work academic workers are expected to do.

At universities across the country, branches are planning to do more than withdraw their labour for the day. For example, planning teach outs and a demonstration in London on the 28th of February.

Between branches, activists are organising to coordinate action. You can join the Facebook group here.

4. We need to do more than the UCU strike!

In my last job, I would usually only come onto campus to teach. When I was not teaching, my only interaction with the university management was by email. This was regardless of whether I was physically “there” or not. While away from campus I spend my time on research. This makes striking in universities feel different to many workplaces. It is therefore worth briefly considering the academic labour process and how it can be effectively disrupted.

If we isolate out the activities of the university to just academics (which while useful for now, is also a terrible idea – and I’ll return to this in the next paragraph), what is the aim of the work? The aim is twofold. First, to sort potential workers for the job market. This involves teaching, marking, and awarding of degrees. Second, doing “research.” This is something that most of the time does not matter to the university until the REF. This is an expensive and subjective attempt to “measure” the quality of work approximately every five years. In addition to this, academic workers have to do increasingly larger amounts of administrative work.

So what does this mean for effective strike action in the university today? During a previous dispute, my local branch asked the national UCU if we could organise an email boycott as part of the strike. They replied by email (without any irony) that this would not be possible as it would be “too effective.” As many precarious academic workers have no permanent offices, this means it is often management’s only way to communicate.

The university is much more than just the academics. My last department employed more support staff than academics. This includes technical staff, cleaners, groundskeepers, catering, and so on. It would take many days (and perhaps even weeks) for my employer to notice I had withdrawn my labour. But when cleaners strike the effects are felt the next day. While academics have seen their conditions eroded over the last ten years, the cleaners in central London have been a beacon of precarious workers struggle.

Many of the plans for the strike at different universities sound exciting, but imagine a strike in which all the workers of the university walk out. For many academics, this would mean getting to know the other workers upon which the university relies. It means seeing that while we have relatively good conditions, we also have the freedom to organise not found in many workplaces.

5. We need the UCU!

The UCU is a large union with an established structure and resources. It is involved in national pay bargaining - the setting of rates of pay across every university in the country. This means collectively negotiating between the union and the all of the employers. While it has not used this capacity in a long time, this means the UCU can organise national strike action with all universities at once.

UCU is the largest trade union for academic workers. In many university departments the majority of academic workers are members. This means branches can act as a focus for workplace concerns and organising in universities.

Many branches across the country spend huge amounts of time and resources on case work. This involves supporting vulnerable workers against management. The expertise within the union has been developed over many years, with some successes on a local level and a layer of militant activists.

6. We need more than the UCU!

This strike is a test of the UCU. Previous struggles – particularly around precarious contracts – have been deliberately held back to wait for the fight over pensions. The result of this strike will be decisive.

There is much we can learn from the alternative unions in London. IWGB and UVW provide powerful examples of successful organising in universities. This is why I organise in my workplace and am a member of both UCU and IWGB. At Senate House (part of the University of London), IWGB members will be walking out on the first day of the UCU strike. This is the kind of action we need to win the dispute.

Rather than starting with the union - in this case UCU - we need to begin instead with the workplace. By understanding how we work, we can best plan to disrupt the workplace - particularly by organising with other workers in the university. It is this kind of organising that can challenge our employers and build power.

Although their work was very different to contemporary academic workers, the Clyde Workers’ Committee laid out an important principle for the relationship between workers and the union:

We will support the officials just as long as they rightly represent the workers, but we will act independently immediately they misrepresent them. Being composed of Delegates from every shop and untrammelled by obsolete rule or law, we claim to represent the true feeling of the workers. We can act immediately according to the merits of the case and the desire of the rank and file.

As the strike begins, this is an important principle to keep in mind. We have voted for strike action to defeat the pensions changes, anything less is a failure.

On the eve of the UCU strikes we should all be ready to fight as hard as possible for victory – but soon after we need to have a discussion about what happens next.

At Notes from Below, we will be on picket lines handing out “the University Workers” bulletin, which can be found online here. If you want to join a picket line, there is information about Senate Househere.

Jamie Woodcock is a researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute, author of Working the Phones, and a member of the Class Inquiry Group. Twitter:@jamie_woodcock.

The Explanatory Value of the Theory of Uneven and Combined Development

Susan Dianne Brophy has a PhD in Social and Political Thought (York University - Toronto, Canada) and is currently an Assistant Professor in Legal Studies (St. Jerome's University - Waterloo, Canada). For more info see https://uwaterloo.ca/scholar/s3brophy. An earlier draft of this paper was presented at the HM London 2016 conference.

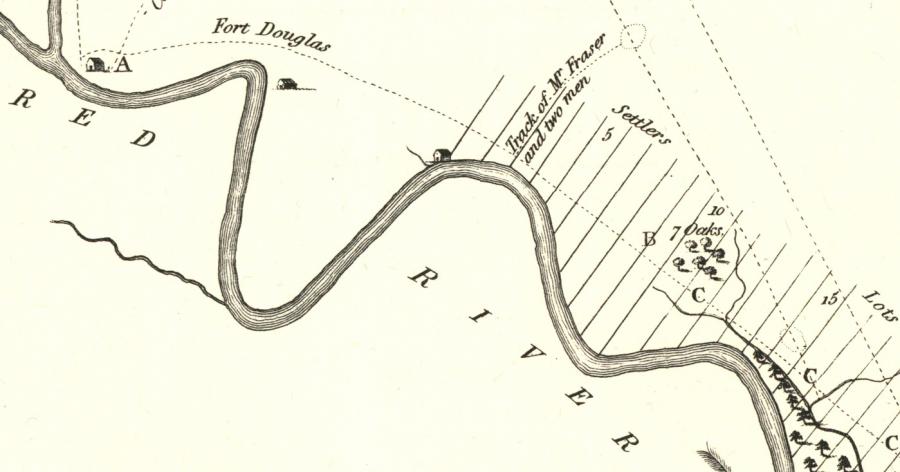

Picture: “Red River Settlement 1818 [1910]” by Wyman Laliberte is licensed underCC BY 2.0 / Cropped from original

Capitalism does not evolve in either a linear or uniform way. Unevenness, exemplified by different levels of market penetration or industrial development, may be present in a single jurisdiction, while non-capitalist elements may combine with capitalist forces of production to varying degrees. Articulated in this way, the uneven and combined development (UCD) of capitalism is a demonstrable fact, one so assumed as a given that some hold it up as a ‘law’ of development.[1] So commonsensical is UCD that in the pages of New Left Review two decades ago, Justin Rosenberg pondered why an historical perspective that offers such ‘retrospective simplicity’ took as long as it did to emerge in the first instance.[2] This supposed simplicity, however, points to another curiosity: how can the manifestly obvious also (and still) be so contentious?

Rosenberg’s instincts in 2013 were right. To answer this question means to journey into the philosophical wilds where this concept first took root;[3] if one wishes to study the philosophical grounds of UCD, the terminus is not Trotsky alone,[4] but the broader philosophical foundation of Marxism: dialectical materialism.

Debates about UCD continue today, especially but not exclusively in the arenas of historical sociology[5] and international relations (IR) theory.[6] Among the more interesting disputes are those between Political Marxists (generally proponents of Robert Brenner’s class-focused approach to the transition to capitalism) such as Benno Teschke,[7] and UCD-proponents in IR, such as the recent work by Alexander Anievas and Kerem Nişancıoğlu.[8] There are two intersecting fault-lines in this debate, one having to do with the temporal scope of UCD, and the other raising questions as to the explanatory value of the concept. Presumably, if we could just agree on whether UCD is a transhistorical law or a characteristic exclusive to capitalism, then we can settle the matter of its substantive utility. However, this quick fix does nothing to solve the underlying tautology, which holds that UCD explains the development of capitalism, but at the same time UCD itself requires further elaboration — or more succinctly, the notion ‘that UCD explains UCD’.[9] Taxed with such deep-seated liabilities, I maintain that a closer look at the dialectical materialist premises of UCD may lead to a resolution. Recast in these terms, the law of UCD is simply an expression of dialectical materialist logic arrived at through the application of an historical materialist methodology. From this philosophical reframing we can draw logical clarity, which will at least dampen the apocryphal renderings of UCD, and maybe even reinstate it as an instructive framework for the study of historical transformation.

Trotsky, to start

Let us turn our attention first to Trotsky, who is among the principal originators of the notion of UCD as an historical law.[10] Even a basic understanding of historical materialism compels us to acknowledge that Trotsky begins with an account of history — the Russian Revolution in meticulous detail — and from that evidence posits UCD as a law of history.[11] The Russian case imprints on him the ‘planless, complex, combined character’ of development,[12] as he describes its historical transformation as occurring in ruptures and ‘leaps’.[13] He observes gaps and disparities, where developmental leaps are not only possible but inevitable under certain conditions; this, he identifies as uneven development. At the same time, he notes the ‘drawing together of the different stages’, where the disassociated becomes unified to establish a new developmental amalgam; this, he identifies as combined development.[14] With leaps, ruptures, disparities, and unevenness, on the one hand, and fusion, interdependency, adaptations, and combination, on the other, we have evidence of the contradictory forces that electrify historical transformation.[15]

Before us is the blueprint for the dominant controversies that persist today, which I only sketch-out here, but will return to in more detail later. First, if Trotsky’s law of UCD is the product of his historical analysis of social relations endemic to capitalism, is it either permissible or wise to assume that the law can also apply transhistorically in a variety of epochs that are characterized by non-capitalist modes of production? Second, even if the law only applies to capitalist development, what is its broader explanatory value beyond the tautological claim that capitalism develops in an uneven and combined manner because...capitalism develops in an uneven and combined manner? Intractable as these disputes appear, we can also see the prospects of a resolution once we embark on a careful dissection of the inner-workings of UCD.

Trotsky arrives at the law of UCD because he understands historical change as essentially conditional, subject to geography and timing — bolting forward or lurching slowly, always in movement. As a law of history it is both generalized and abstract, but as a law of history derived from the application of an historical materialist methodology it reflects the volatility and contradictions of actual social transformation. I think of this as a type of rule of unruliness, which, for Trotsky, anchors two other definitive claims: the rejection of the economic determinism that gives rise to a stagist approach to history,[16] and the theory of permanent revolution. Since remnants of previous eras of production are carried over and come into conflict with new productive means, economic change is revealed as highly contingent and susceptible to an array of internaland external (i.e. international) influences.[17] Revolution, likewise, must then be understood as interminable because no successive phase is ever complete until the class system itself has been decisively overthrown.[18] In unequivocally dialectical terms, ‘the process of development’ is the uninterrupted but nonlinear disintegration and integration of discrete phases wherein disparate facets of historical transformation interpenetrate to comprise a ‘totality’, or more precisely, a ‘differentiated unity’.[19]

Almost by stealth, but in no respect by accident, we have before us the philosophical tenets of dialectical materialism — negation, contradiction, and synthesis — each of which serves a common logical imperative: what the adept-but-underrated materialist dialectician, Frantz Fanon, referred to as the ‘perpetual interrogation’ of the relation between the concrete and the abstract.[20] I view the law of development that Trotsky advances as an iteration of this dialectical materialist imperative; the two are inseparable, if not synonymous, and to ignore this deep association is to misunderstand the philosophical foundations of UCD. It follows, then, that the most egregious distortions of UCD in contemporary debates result from the lack of attention to (at best), or outright denial of (at worst), this explicit correlation.

Debates adrift

From the divergences in the relative fidelity that scholars insist upon when it comes to Trotsky’s original formulations we can trace a diversity of expectations with regard to UCD. Though I account for only a selection of these offerings, my sampling is enough to showcase both the distortions that characterize contemporary debates about UCD, and the value of a return to dialectical materialism as a riposte.

On the first page of the first chapter of Late Capitalism, Ernest Mandel begins his defense of the law of UCD with a note on the relation between the abstract and the concrete.[21] Almost embarrassed to raise such an elementary consideration, he anchors this section with a quote from theGrundrisse that spans three-quarters of a page. He then offers a deft summary — supplemented by Lenin’sPhilosophical Notebooks — in the form of four rules that serve to guard against over-simplification of Marx’s method: first, the concrete is both the starting focus and the end objective; second, the abstract and the concrete give rise to each other in a process of dialectical progression; third, this manner of progression unifies ‘analysis and synthesis’, keeping intact the mutually constitutive relation between the abstract and the concrete as a ‘unity of opposites’;[22] and fourth, each successive phase of cognition must be ‘tested in practice[23] as a means of validation. With this philosophical logic at hand, he undertakes to comprehend the distinctiveness of late capitalism, first by identifying the laws of capitalism in general.

Mandel’s interpretation of the development of capitalism turns on the law of UCD, which he thinks distinguishes him from those that assume equilibrium as a law.[24] For Mandel, disequilibrium is the ‘essence of capital’;[25] how and to what end surplus-value can be extracted and accumulated in one area is related to how and to what end surplus-value can be extracted and accumulated in another. The ‘juxtaposition of development and underdevelopment’ that Mandel observes leads him to endorse UCD as a law,[26] one that he considers universal insofar as it applies to capitalist development in general,[27] but not transhistorical in the sense that it applies to other non-capitalist epochs. On the surface, we can grant Mandel this differentiation between the universal and the transhistorical; peel back a layer, though, and we see how an abuse of his own rules leads to confusion about the temporal scope of UCD and, by extension, to tautological inferences.

Arguably, Mandel is more concerned with a defense of the abstract laws of capitalism, and of Marxism in general, than with understanding capitalism as a differentiated unity undergoing constant change. This is Chris Harman’s position in his scathing review of Late Capitalism, in which he argues that processes of perpetual change also implicate the laws themselves, and that in failing his own philosophical tenets, Mandel ‘replace[s] explanation by eclecticism’.[28] Once we stop querying the abstractions, they lose validity and become relics that can only be deployed in an eclectic fashion. This may explain what happens to the law of UCD as it becomes a hallmark specific to capitalist development; UCD’s temporal restriction banishes it as an idiosyncrasy of capitalism, in effect hypostatizing the abstraction and dissolving the ‘unity of opposites’ into total identification. When the abstract is assumed as the concrete, the explanatory value of the law of UCD gives way to a tautology: the fact of UCD explains the law of UCD, which is taken as a fact.

What if we just stopped calling the law of UCD a ‘law’, would that not fix the problem? Marcel van der Linden offers this very suggestion. Scientific laws serve a predictive purpose, but van der Linden is not convinced that the ‘law’ of UCD can achieve such an outcome with any reliability. He argues, therefore, that the ‘law’ of UCD is ‘insufficiently specific’ and as such, is not a ‘law’ at all.[29] In a way Jon Elster offers a like statement about UCD, but with a more renunciatory flair. Analytic Marxist as he is, to his mind UCD is ‘vapid’, and falls in with other Marxist theories he likewise finds suggestive and elusive.[30] In support of this dismissal, he contends that there is a lack of clarity with respect to how the ‘objective’ elements (i.e. the economic conditions) and the ‘subjective’ elements (i.e. the political or social temperament) would ever combine in such a way that would allow us to predict where and how a communist revolution would occur. Whereas van der Linden maintains that once we rid the yoke of ‘law’ from UCD, we can better examine the social relations that occasion ‘historical leaps’,[31] Elster rejects UCD altogether because of its meagre predictive value. Yet both challenge UCD as a static abstraction, and both begrudge the abstraction because it loses sight of the concrete.

But no, we cannot just to strip the term ‘law’ from our understanding of UCD because in doing so we risk going too far in the other direction: that is, sacrificing the dialectic for materialism and undermining the logic that brought us to UCD in the first place. Elster would be fine with this outcome, but that only goes to show how closely identified UCD is with dialectical materialism to start with. Perhaps the answer is to keep the notion of the ‘law’, but extend its application to non-capitalist epochs, and in doing so, arrive at a less restrictive understanding of the abstract law — one that allows for the further differentiation of the concrete. This is what Rosenberg brings to IR theory.

For Rosenberg, UCD serves his broader aim, which is to introduce a more systematic understanding of the history of social transformation to the field.[32] He suggests UCD as a way into the debate because it brings ‘the social’ to bear on ‘the international’ at the same time that it offers ‘a general abstraction of the historical process’ (read: UCD as not exclusive to capitalism).[33] Related to the second point, he argues that to treat UCD as an exclusively capitalist ‘side-effect’ is to distort Trotsky’s original formulation, which presents UCD as an historical law of a more temporally-generalizable scope.[34] In response to Rosenberg’s interpretation of Trotsky, Alex Callinicos (arguably in a manner reminiscent of Mandel) makes the case for a ‘mode-of-production’ approach, drawing on concepts fromCapital to accentuate the specific ways that capitalism emerges in certain geographies and periods.[35] Although he does acknowledge that UCD, per Trotsky’s vision, resists economic essentialism,[36] this admission does not protect Callinicos himself from the charge that he approaches UCD in ‘exclusively economic terms’.[37] Overall, this productive exchange between Callinicos and Rosenberg in IR theory reflects the more general debate over UCD. Applied in one manner, UCD as an analytical framework can account for ‘the social’ and is stalwart against reductive economism. From another angle, it over-generalizes and as such is insufficiently explanatory, rendering its applicant unable to account for the particularities of how capitalism evolves.

The 2008 Callinicos/Rosenberg exchange led to a special section on UCD published by the Cambridge Review of International Affairs in 2009. Here, we tread the same disputed terrain as before, but with a concerted interest in the contentiousness of Rosenberg’s reading of UCD as tranhistorical. In the lead essay, Neil Davidson argues that the UCD that Trotsky speaks to is not the transhistorical UCD that Rosenberg identifies with, but is rather a particular moment in Russian history that ‘only arrives with capitalist industrialisation’.[38] Sam Ashman concurs, attesting that capitalism engenders a specific type of unevenness that is not in fact transhistorical, so by deploying UCD as a transhistorical law we lose sight of the unique facets of capitalism that gave rise to UCD in the first place.[39] A like assessment comes from Jamie C. Allinson and Alexander Anievas, who claim that it is only possible to arrive at UCD once one acknowledges that the drivers in capitalist expansion (competition and surplus-value) compel as much.[40] This starting point necessarily limits the transhistorical applicability of UCD, although they find some worth in how UCD links pre-capitalist and capitalist history. That Anievas in particular finds value in UCD is evidenced by the monograph he later co-authors with Nişancioğlu,How the West Came to Rule. The authors identify three applications of UCD: as an abstract law, as a methodology, and (their preferred approach) as a theory,[41] and argue — in line with Rosenberg’s view — that the best part of UCD is Trotsky’s promotion of the international as a force in historical transformation.[42]

Among the more acerbic commentaries on Rosenberg’s approach to UCD is Teschke’s from 2014. Teschke is skeptical of the IR twist on UCD, indicting it as the regrettable offspring that resulted from the union between neo-realism and structuralism.[43] For him, the collapsing of UCD as a law and as a theory in IR undermines its explanatory promise by ensconcing it in abstraction,[44] an eventuality he finds insupportable because it violates a key tenet of Marx’s dialectical method,[45] namely the ‘perpetual interrogation’ of the relation between the abstract and the concrete. Indeed, what Teschke finds disconcerting is that which others have already flagged: the hypostatization of the abstract law that both loses sight of the concrete and leads to a tautology. I would add, however, that in what is otherwise a trenchant study, Teschke’s dismissal of UCD is disingenuous. He wrests any trace of dialectical materialism from his understanding of UCD, inserts a tautology in the resultant void, and declares that ‘it remains unclear what drives uneven and combined development’.[46] The transhistorical scrap that is left over is incapable of identifying the productive role of ‘political agency’ in historical development,[47] and as such, should be rejected.

Taken solely as an abstract law, the simplicity of UCD undermines its anticipated explanatory value. At first blush, UCD purports to explain the development of capitalism by providing a template for understanding economic change; however, this template proves insufficient, leading to the realization that the concept of UCD itself requires further elaboration. Teschke refers to this as the inescapable ‘flat tautology’ of UCD.[48] His diagnosis exposes the terminal flaw of UCD; yet this palliative assessment is antithetical to dialectical materialism and is a misleading consignment of the explanatory value of UCD. Specifically, Teschke treats as synonymous the notion of UCD as an abstract law and historically-differentiated UCD, which amounts to a desertion of dialectical materialist methodology that leads to the tautological trap. Far from inevitable or fatal, the trap is of his own making: UCD can be diagnosed as a ‘flat tautology’ only when the mutually constitutive dialectic between the abstract and the concrete has been flattened.

As I have shown, some cast the law of UCD as a transhistorical, overly-generalizing imposter that is beyond redemption, yet when we repatriate UCD back to the realm of dialectical materialism, such grim diagnoses are insupportable for two reasons. First, UCD as an abstract law is the logical product of the dialectical materialist logic in practice, and since this logic ‘perpetual interrogation’ cannot abide such a tautological assertion,[49] those who banish UCD on the grounds of its tautological character also forsake its dialectical materialist essence. Second, UCD is tautological only if it remains within the confines of a static abstraction. Since the duty of the dialectical materialist is to concretize abstractions (and vice versa), UCD must be understood as a clarion call for further analysis, or as Anievas and Nişancıoğlu explain, it is an undertaking that ‘proceeds through a series of descending levels of abstraction, further approximating, and reconstituting in thought, empirical reality along each step of the way’.[50] We are needlessly drawn down the tautological path when we abandon the core of the dialectical materialist philosophy, namely by mistaking the simple abstraction for a concrete category.[51] Instead of deploying these concepts interchangeably toward self-defeating ends, we should be mindful of the mutually constitutive relation between the law of UCD as a simple abstraction and historically-differentiated UCD as a concrete category.

A riposte

While Teschke is wary of the ‘circular result that UCD explains UCD’,[52] it is an essential principle in dialectical materialist analysis that we should not take comparable concepts as identical, fixed abstractions, as Trotsky reminds us, ‘in reality “A” is not equal to “A”’.[53] With reference to measurements of sugar, he explains that a pound of sugar on one scale is not equal to a pound of sugar measured on a more exacting device. Absolute correspondence requires formalism and fixedness, but where there is no change (temporal or otherwise), there is no life or ‘existence’.[54] Meanwhile, ‘[d]ialectical thinking analyses all things and phenomena in their continuous change, while determining in the material conditions of those changes that critical limit beyond which “A” ceases to be “A”’.[55] From this perspective, the diagnosis of UCD as a ‘flat tautology’ comes into focus as a red herring: UCD is not equal to UCD, unless understood undialectically, and by extension, inconsistently with respect to its originating mode of engagement.

A strong case against a temporally-contained conception of UCD comes from Anievas and Nişancıoğlu, who see the tentacles of UCD as extending beyond European capitalism.[56] In more philosophical terms, however, this persistence of the debate about whether or not UCD is transhistorical stems from the lack of a more apt demarcation between UCD as a simple abstraction versus a concrete category, and is complicated by divergences into formalism that accompany the insistence that UCD is tautological. By focusing on this relation between the abstract and the concrete in more detail, however, we can excavate the entwined roots of dialectical materialism and UCD, which allows us to re-assess what we can reasonably expect from UCD in the study of historical transformation.

We know that fixed abstraction freezes the dialectic and breeds tautology by mistaking the abstract for the concrete, but the way out of this bind requires more than the interrogation of abstraction through concretization. Trotsky insists that the drive to concretize the abstract does not give rise to categorical verdicts on social relations, but in fact that ‘the more concrete the prognosis, the more conditional it is’.[57] For example, we can have, on the one hand, labour as an undifferentiated (abstract) category, and on the other hand, wage labour as a more historically-differentiated category. Although the latter is more historically-specific, it is still an abstract and in no way a settled category;[58] we are only in “the process of ‘true abstraction”’,[59] and not at the end point of our analysis. Indeed, as we proceed with an assessment of historical development, our truth claims about the concrete become increasingly relative. However, we should not confuse this with a descent into pure relativism, doing so would come at the cost of losing the constitutive connection to totality. As Lenin explains, dialectical materialist logic guards against this degeneration because it ‘recognises the relativity of all our knowledge, not in the sense of denying objective truth, but in the sense that the limits of approximation of our knowledge to this truth are historically conditional’.[60] Through the unity of ‘analysis and synthesis’, we keep the differentiation between the abstract and the concrete intact, compelling us toward the interrogation of our very understanding of totality. What we have, then, is a dialectic between relative truth and objective truth, wherein our knowledge of objective truth is conditional, yet objective truth exists unconditionally.[61] In this sense, our comprehension of the unconditional and objective occurs through our comprehension of the conditional and relative, and vice versa.

More than just concretizing the abstract, therefore, it is also a matter of taking what we think of as concrete and holding it up to further analysis, that is, abstracting the concrete. For instance, the contract, as a simple abstraction, appears across various epochs. However, the specific type of contract that is integral to the capitalist mode of production can only be understood as developing its unique form in relation to other specific historical developments. When the simple abstraction is interrogated according to the particulars of a given time and place, it is subjected to ‘the process of ‘true abstraction’’, where we have the union between ‘synthesis’ and ‘analysis’. This involves placing the specific historical developments of the capitalist contract (such as who is allowed to enter into contract at a given time and place) against the abstract concept of the contract (with its early roots in the swearing of oaths).[62] The abstraction interpenetrates the concrete, and although the two categories remain distinct, the historical development of the contract in its capitalist form both assumes and negates the contract as a simple abstraction. In this transformation, the contradictory elements can remain intact to varying degrees, which allows us to comprehend how the contract, effectively a testament to enmity in capitalism, remains connected to the notion of the contract as an expression of fealty in other epochs.

An example that better evinces these dialectical connections is the early settler-colonial context of Canada. With the founding of the first settlement on the prairies in 1812 at Red River (in present-day Manitoba), the feudal contract that bonded servants to the fur trading Hudson’s Bay Company was transforming as some servants became land-holding settlers. For this to occur, the servant had to be ‘set free, to work for himself’ and to ‘be charged as a debtor’ to the company’s store, adopting prototypical bourgeois freedoms along the way.[63] But this was not a simple tale of how the fealty of the servant’s feudal contract was negated by the so-called ‘freedom’ of the settler’s debt-based contract. Crucially, this transformation portended changes to Indigenous peoples’ freedom. The synthesized freedom that was at the core of the settler’s new contractual position was an abstract condition shaped by the reality of what it meant to be a debtor and by the fact that landownership entailed compromises to the freedom of certain Indigenous peoples. The synthesized freedom of these Indigenous peoples, in turn, reflected the reality that their signatures were needed on treaties in order to legitimize the dispossession of land.[64] Seen as ‘unacquainted with control and subordination’, their freedom was recognized by colonial agents in instances that facilitated contract-based relations of dispossession.[65] At Red River at around 1812, therefore, contract-making was a vehicle of change, but the actual process was interpenetrated by abstract concepts of freedom and racial and class realities.

To begin to comprehend the totality of the transformations is to identify a historically-specific manifestation of UCD, which requires close scrutiny of contradictions, negations, and syntheses occurring at a particular historical site and time. In the example provided, the abstract and undifferentiated dimensions of the contract become comprehensible when the relative and historically-specific facets are attended to, which in turn illuminates how abstract elements are differentiated though no less constitutive in actual contractual relations. Even with this brief illustration, we begin to see the uneven and combined dynamics of a specific transformative period, which clarifies the constitutive relation among the contract as an undifferentiated construct, the bourgeois-type freedoms associated with capitalist contracts, and the contract in a still more specific early settler colonial context. By progressing through ‘descending levels of abstraction’, it becomes possible to connect but differentiate the contract as a fixed abstraction in relation to historically-specific practices of contract-making. At the same time, we see how UCD as an abstract, general law and UCD in a more concrete historical context are mutually constitutive, but not identical.

UCD as a law of historical development is the general law abstracted to the extreme; we can consider this an example of a ‘simple category’ insofar as it consists of ‘general abstract determinations, which therefore appertain more or less to all forms of society’.[66] When we talk about the law of UCD as a definitive feature of capitalism (for instance), we have in mind a more specified articulation of the abstracted extreme; we can consider this an example of a more ‘concrete category’ insofar as it pertains to a specific articulation of social relations.[67] Even in its more exclusively capitalist orientation, we are still talking generally about patterns while we progress toward a deeper comprehension. The main point of this differentiation is to recognize that the law of UCD can stand as an extreme abstraction in a truly universal sense, while the law of UCD that applies specifically to capitalism is a more particular articulation of the general. As Rosenberg expounds: ‘the transhistorical and the historically specific can — and indeed must — be combined in the analysis of any concrete particular’, careful all the while not to fold the abstract into the concrete so as to achieve a clearer picture of the totality.[68] This demarcation between the abstract and concrete does not detract in any way from the understanding of UCD as a law of capitalism; in fact, it enhances our understanding of UCD because the discussion is no longer trapped in an either/or paradigm, forcing us to choose between a transhistorical or capitalist-specific version of UCD. From the outset, the logic of dialectical materialism demonstrates the fallacy of this choice. Rather than clarify the matter of UCD, the either/or dilemma over-simplifies it by negating that which we should be analysing: the dialectical relation between the abstract and the concrete. Denial of this essential relation is the first step in the acceptance that ‘“A” is equal to “A”’,[69] which is the port of entry into a philosophical landscape that is entirely hostile to the comprehension of historical development. In this shift, we turn away from the foundational understanding that ‘everything is always changing’ and begin to peddle in ‘fixed abstractions’.[70]

If, even after this more precise demarcation between the abstract and the concrete, we are still inclined to insist that UCD is a phenomenon exclusive to capitalism and that it has no universal dimension, then we must attempt a more convincing argument. The further abstraction of UCD to a more universal level does not imply that the law of UCD that is particular to capitalism also applies universally. No, indeed: there are unique attributes of the UCD of capitalism that do not translate universally, such as market dependency and accumulation through surplus-value. Yet it is much too hasty to say that only where we see capitalism as the dominant mode of production can we then also identify UCD as the general evolutionary pattern, a point evinced by the Red River example. By denying the broader applicability of UCD, we tread perilously close to suggesting — without evidence — that historical development in general does not occur in an uneven and combined manner. So when in history does the process of UCD begin?

Now we can really see what is at stake when we bind UCD so exclusively to capitalism. If we recognize that the law of UCD is, in essence, an expression of dialectical materialist logic, then the impetus to temporally bracket UCD has as a consequence the severing of the dialectic itself. Contradiction, synthesis, and negation become the unique purview of capitalism as the full scale of dialectical materialist development is lost to selective applications of general laws.

Consider, besides, that we already grant such flexibility to the law of UCD in another domain: geography. Trotsky conceptualized the law of UCD through a detailed study of the history of the Russian Revolution, but it would be absurd to then reason that the law of UCD has no currency outside of the Russian case. That the law of UCD extends beyond the specific jurisdiction of revolutionary Russia is an implicit acknowledgement that the law itself points to an abstract, generalizable and generalized pattern of development that may be present in other places and eras. It is prudent to also note that Trotsky’s observations that underpin the law of UCD derive from a society and economy in transition, as was the case in revolutionary Russia, which was not a bastion of capitalism at the time.

Conclusion

The law of UCD, unencumbered by the fallacious either/or dilemma that occasions undialectical analysis, is reinvigorated by dialectical materialist philosophy. The basic differentiation between the law of UCD in general as a simple abstraction and the law of UCD in capitalism as a more concrete category accomplishes two basic, but crucial tasks: first, it sheds the notion of the law of UCD as a fixed abstraction; second, it forces us to strengthen our analysis of UCD as a law of capitalism. In two moves, we leave behind what was once fertile ground for tautological inferences. By the end of our journey, we might even look back to where we began and admonish ourselves for once holding the naive belief that UCD should ‘explain’ anything. Such an expectation treats UCD as a ‘mere proof-producing instrument’,[71] and implies that instead of ‘perpetual interrogation’, we should be satisfied with the half-truths of partial interrogations. The law of UCD taken as a fixed abstraction on its own explains nothing, nor should we expect it to.

But to conclude on this basis that the law of UCD has no value is also wrongheaded; you might as well say that dialectical materialism has no value. Dialectical materialist logic is intrinsic to historical development itself, or as Marx’s explains, ‘the course of abstract thinking which advances from the elementary to the combined corresponds to the actual historical process’.[72] When we espouse dialectical materialist logic, we gradually deepen our comprehension of the nature of the correspondence between the actual and the idea, and by extension, our understanding of the totality of historical transformation.[73]

It is not until we re-engage the dialectical materialist logic that we can begin to appreciate the relation between the law of UCD in as an undifferentiated constant, and the law of UCD in capitalism (or in other, non-capitalist times and places) as an historically-differentiated category. This perspective releases UCD from the constraints of the lingering disputes and encourages more meaningful assessments of historical transformation. Key advancements have already been made along these lines by Anievas and Nişancıoğlu,[74] and by expanding the explanatory framework beyond IR, still more are within reach. Like the laws of dialectics in general, UCD is not a ‘mere proof-producing instrument’, but is an abstract law that was arrived at through historical analysis. What is more, as an abstract law, it must always be in the process of being objectively verified according to a dialectical materialist logic; anything less is to misinterpret the abstract as truth, rather than a conditional finding. That, ultimately, is the real value of the law of UCD: it is an expression of one’s unconditional commitment to comprehend historical development through ‘perpetual interrogation’.

[1] Leon Trotsky,History of the Russian Revolution, trans. Max Eastman (Chicago, 2008); George Novack,Understanding History: Marxist Essays (New York, 1974); Ernest Mandel,Late Capitalism, trans. Joris De Bres (London, 1975).

[2] Justin Rosenberg, ‘Isaac Deutscher and the Lost History of International Relations’,New Left Review, I, no. 215 (1996), 6.

[3] Justin Rosenberg, ‘The ‘Philosophical Premises’ of Uneven and Combined Development’,Review of International Studies, xxxix (2013).

[4] Ibid., 587.

[5] Benno Teschke, ‘IR Theory, Historical Materialism and the False Promise of International Historical Sociology’,Spectrum, vi (2014); Sébastien Rioux, ‘International Historical Sociology: Recovering Sociohistorical Causality’,Rethinking Marxism, xxi (2009).

[6] Jessica Evans, ‘The Uneven and Combined Development of Class Forces: Migration as Combined Development’,Cambridge Review of International Affairs, xxix (2016); Sam Ashman, ‘Capitalism, Uneven and Combined Development and the Transhistoric’,Cambridge Review of International Affairs, xx (2009). Notable also is the emergence of UCD in literary studies.

[7] Robert Brenner, ‘Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe’,Past & Present, lxx (1976); Robert Brenner, ‘Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe: The Agrarian Roots of European Capitalism’,Past & Present, xcvii (1982).

[8] Jamie C. Allinson and Alexander Anievas, ‘The Uses and Misuses of Uneven and Combined Development: An Anatomy of a Concept’,Cambridge Review of International Affairs, xx (2009); Alexander Anievas and Kerem Nişancıoğlu,How the West Came to Rule: The Geopolitical Origins of Capitalism (London, 2015).

[9] Benno Teschke, ‘IR Theory, Historical Materialism and the False Promise of International Historical Sociology’,Spectrum, vi (2014), 32.

[10] Some do trace the more lauded twentieth century accounts of UCD to the nineteenth century writings by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, see Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels,Collected Works of Marx and Engels, Economic Works 1857-1861, vol. 28 (New York, 1986), 435; Jairus Banaji,Theory As History: Essays on Modes of Production and Exploitation (Chicago, 2011), 63; Neil Smith,Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space, 3rd edition (Athens, GA, 2008); David Harvey, ‘Notes Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development’, inSpaces of Neoliberalization: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development, vol. 8, Hettner-Lectures (Stuttgart, 2005); Radhika Desai,Geopolitical Economy: After US Hegemony, Globalization and Empire (New York, 2013), 52, 39–43. But it is also the case that many UCD theorists acknowledge this inheritance only in passing, see George Novack, ‘The Law of Uneven and Combined Development and Latin America’,Latin American Perspectives, iii (1976). Lenin meanwhile addressed uneven development, namely in his 1917 pamphlet on imperialism, which focuses on the expansive nature of capitalism and its destabilizing effect on international affairs. Attendant on, if not inherent to, this expansionism is a capitalist nation’s quest for exclusive control over other territories which were at the heart of ‘Great War’. Lenin refers to how ‘[t]he uneven and spasmodic development of individual enterprises, individual branches of industry and individual countries, is inevitable under the capitalist system’, see Vladimir Ilyich Lenin,Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism: A Popular Outline (New York, 1939), 62. He also argues that England could not have achieved the status of the world’s premier capitalist state without an imperialist monopoly on the raw resources that drove the advancement of domestic industries. He later revisits these themes in the pamphlet’s coda, where he links capitalism’s expansionist compulsion to the increasing unevenness between states (ibid., 125). Although his understanding of imperialism as a ‘stage’ resists a notion of combined development, the thrust of his indictment of imperialism nevertheless turns on a particular conception of unevenness.

[11] Trotsky,History of the Russian Revolution, 5.

[12] Ibid., 4.

[13] Ibid., 9.

[14] Ibid., 5.

[15] Ibid., 4.

[16] Michael Löwy,The Politics of Combined and Uneven Development: The Theory of Permanent Revolution (London: 1981), 46 & 48.

[17] Leon Trotsky,The Permanent Revolution & Results and Prospects (Seattle, 2010), 269–70.

[18] Ibid., 143.

[19] John Rees,The Algebra of Revolution: The Dialectic and the Classical Marxist Tradition (London & New York, 1998), 278–9.

[20] Frantz Fanon,Peau noire, masque blancs (Paris, 1952), 23.

[21] Mandel,Late Capitalism, 13.

[22] Ibid., 14.

[23] Vladimir Ilyich Lenin,Collected Works, vol. 38 (Moscow, 1976), 317.

[24] Mandel,Late Capitalism, 28.

[25] Ibid., 27.

[26] Ibid., 86.

[27] Ibid., 23.

[28] Chris Harman, ‘Mandel’s Late Capitalism’,International Socialism ii (1978).

[29] Marcel van der Linden, ‘The “Law” of Uneven and Combined Development: Some Underdeveloped Thoughts’,Historical Materialism xv (2007), 161.

[30] Jon Elster, ‘The Theory of Combined and Uneven Development: A Critique’, inAnalytical Marxism, ed. John Roemer (Cambridge, 1986), 55–6.

[31] van der Linden, ‘The “Law” of Uneven and Combined Development: Some Underdeveloped Thoughts’, 162.

[32] Sébastien Rioux, ‘International Historical Sociology: Recovering Sociohistorical Causality’,Rethinking Marxism, xxi (2009), 586.

[33] Rosenberg, ‘The “Philosophical Premises” of Uneven and Combined Development’, 594.

[34] Ibid., 586.

[35] Alex Callinicos and Justin Rosenberg, ‘Uneven and Combined Development: The Social-Relational Substratum of “the International”? An Exchange of Letters’,Cambridge Review of International Affairs, xxi (2008), 102.

[36] Ibid., 101.

[37] Desai,Geopolitical Economy, 144. It is possible to attribute this narrower focus to the scope of Callinicos’s study, which focuses less on ideological or social considerations; however, one of the defining features of combined development is that ‘[i]t is much more than an economic phenomenon, but captures the totality of relations constitutive of a social order as a whole’, Anievas and Nişancıoğlu,How the West Came to Rule, 49.

[38] Neil Davidson, ‘Putting the Nation Back into “the International”’,Cambridge Review of International Affairs, xx (2009), 18.

[39] Sam Ashman, ‘Capitalism, Uneven and Combined Development and the Transhistoric’,Cambridge Review of International Affairs xx (2009), 31.

[40] Jamie C. Allinson and Alexander Anievas, ‘The Uses and Misuses of Uneven and Combined Development: An Anatomy of a Concept’, 57.

[41] Alexander Anievas and Kerem Nişancıoğlu,How the West Came to Rule, 58.

[42] Ibid., 7.

[43] Teschke, ‘IR Theory, Historical Materialism and the False Promise of International Historical Sociology’, 12.

[44] Ibid., 28.

[45] Ibid., 39.

[46] Ibid., 32.

[47] Ibid., 37.

[48] Ibid., 48.

[49] Lenin,Collected Works, 1976, 38: 282.

[50] Anievas and Nişancıoğlu,How the West Came to Rule, 51.

[51] Marx and Engels,Collected Works of Marx and Engels, Economic Works 1857-1861, 28: 39; Banaji,Theory as History, 47.

[52] Teschke, ‘IR Theory, Historical Materialism and the False Promise of International Historical Sociology’, 32.

[53] Leon Trotsky,In Defense of Marxism (New York, 1942), 50.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid., 51.

[56] Anievas and Nişancıoğlu,How the West Came To Rule, 56-7.

[57] Ibid., 174.

[58] Banaji,Theory as History, 40.

[59] Ibid., 59.

[60] Vladimir Ilyich Lenin,Collected Works (Moscow, 1908), 14: 137.

[61] Ibid., 136.

[62] Giorgio Agamben,The Time That Remains: A Commentary on the Letter to the Romans, trans. Patricia Dailey (Stanford, 2005), 119; Giorgio Agamben,The Sacrament of Language: An Archaeology of the Oath, trans. Adam Kotsko, vol. II,3, 9 vols., Homo Sacer (Stanford, 2011); J. G. Manning, ‘The Representation of Justice in Ancient Egypt,Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities xxiv (2012), 111.

[63] Thomas Douglas Selkirk, ‘Instructions to Miles McDonell,’ 1811. Reel C-1. Library and Archives of Canada - Selkirk Collection, 180. For more analysis of Indigenous peoples’ labour during the commercial fur trade, please see my forthcoming essay inSettler Colonial Studies, titled ‘Reciprocity as Dispossession: A Dialectical Materialist Analysis of the Fur Trade’.

[64] This is what occurred at the same site in 1817 with the ‘Selkirk-Peguis Treaty’.

[65] George Prevost, ‘Instructions for the Good Government of the Indian Department, 1812,’ inCollections and Researches Made by the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society (Lansing: Robert Smith & Co., State Printers and Binders, 1895), 23: 87.

[66] Marx and Engels,Collected Works of Marx and Engels, Economic Works 1857-1861, 28: 45.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Rosenberg,The Follies of Globalisation Theory, 72.

[69] As Anievas and Nişancıoğlu explain, leaving UCD intact as a “‘general abstraction’ ... would surely pose a problem: decontextualised from any conception of historically distinct social structures, the precise scales, mechanisms and qualitative forms of unevenness and combination ... could hardly be illuminated’,How the West Came to Rule, 51.

[70] Trotsky,In Defense of Marxism, 51.

[71] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels,Collected Works of Marx and Engels: Friedrich Engels (New York, 1987), 25: 125.

[72] Marx and Engels,Collected Works of Marx and Engels, Economic Works 1857-1861, 28: 39.

[73] Lenin,Collected Works, 1976, 38: 140.

[74] See also my essay inLaw and Critique, titled ‘An Uneven and Combined Development Theory of Law’ (2017).

Luxemburg’s critique of bourgeois feminism and early social reproduction theory

Ankica Čakardić is an assistant professor and the chair of Social Philosophy and Philosophy of Gender at the Faculty for Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. Her research interest include Marxist critique of social contract theory, Political Marxism, Marxist-feminist and Luxemburgian critique of political economy, and history of women’s struggles in Yugoslavia. She is currently finishing her book on the social history of capitalism, Hobbes and Locke. A longer version of this paper, presented at the 2017 London Historical Materialism conference, has been published in the journal's Issue 25.4 as 'From Theory of Accumulation to Social-Reproduction Theory: A Case for Luxemburgian Feminism', available in advance here.

The Accumulation of Capital

Luxemburg did not write many texts on the so-called ‘woman question’.1 However, that does not mean that her work should be omitted from a feminist-revolutionary history. On the contrary, it would be highly inaccurate to claim that her works and, specifically, her critique of political economy lack numerous reference-points for the development of progressive feminist policy and female emancipation, throughout history and today. With Luxemburg’s several essays on the ‘woman question’ and several key theses from her The Accumulation of Capital, let us try to take Luxemburg’s theory a step further. Is it possible to speak of a ‘Luxemburgian feminism’? What does Luxemburg’s critique of bourgeois feminism stand for?

On the eve of WWI, after about fifteen years of preparation, Rosa Luxemburg published The Accumulation of Capital (Berlin, 1913), her most comprehensive theoretical work and one of the most relevant and original classical works of Marxist economics.2The Accumulation of Capital: A Contribution to an Economic Explanation of Imperialism was a follow-up to theIntroduction to Political Economy which Luxemburg wrote while preparing her lectures on political economy, held between 1906 and 1916 and delivered at the German Social-Democrats’ Party School.3 Briefly put, The Accumulation of Capital sought a way to scientifically study and explain the conditions of capitalist monopolisation, extended reproduction and imperialism, while taking into account the dynamic relation between capitalist and non-capitalist spatiality. Luxemburg held that Marx had neglected capital’s spatial determination, while in his critique of capital he had centred exclusively on ‘time’, i.e. the temporal dimension of the internal dynamics of capitalist reproduction. In contrast, Luxemburg ‘sought to show that capital’s inner core consists of the drive to consume what is external to it – non-capitalist strata’.4 Luxemburg’s goal was to articulate her own theory of extended reproduction and critique of classical economics, which would contain not only a temporal but also a ‘spatial analytical dimension’. This spatial determination of capitalist accumulation Peter Hudis has termed ‘dialectics of spatiality’.5

Friends and enemies alike piled sharp criticism upon Luxemburg for noting Marx’s ‘glaring inconsistencies’, as she believed, the ‘defects’ of his approach to the problem of accumulation and expanded reproduction from the second volume of Capital.6 In a letter to Franz Mehring referring to critiques of her The Accumulation of Capital, she wrote:

In general, I was well aware that the book would run into resistance in the short term; unfortunately, our prevailing ‘Marxism’, like some gout-ridden old uncle, is afraid of any fresh breeze of thought, and I took it into account that I would have to do a lot of fighting at first.7

Lenin stated that she ‘distorted Marx’,8 and her work was interpreted as a revision of Marx, in spite of the fact that it was Luxemburg who mounted a vehement attack on the revisionist tendencies within the German SPD. In opposition to the Social Democrats who grouped around ‘epigones’ and an opportunistic current of political practice which ‘corrected’ Marx into a gradual dismissal of socialist principles, revolutionary action and internationalism, Luxemburg insisted on harnessing a living Marxist thought in order to offer more-precise responses to and explanations of the growing economic crisis and newly-appearing facts of economic life. While Luxemburg’s works on political organising, revolutionary philosophy, nationalism or militarism are often analysed by scholars of her thought, few authors have tried to provide a systematic retrospective of Luxemburg’s economic theory and its legacy, or offer a contemporary Luxemburgian analysis of political economy.9 In the words of Ingo Schmidt: ‘Leftists interested in Luxemburg’s work looked at her politics but had little time for economics’.10

Although The Accumulation of Capital was met with severe criticism upon publication, by the opportunistic-reformist and revisionist elements of the SPD, as well as by orthodox Marxists led by Karl Kautsky, it was not only her work that was criticised as ostensibly suspect in its Marxism. These critics often used cheap psychological and conservative naturalising arguments that were meant to undermine the credibility of Luxemburg’s work and expose it as inept and insufficiently acquainted with Marxist texts. A good example of this type of criticism is provided by Werner Sombart, who stated in hisDer proletarische Sozialismus:

The angriest socialists are those who are burdened with the strongest resentment. This is typical: the blood-thirsty, poisonous soul of Rosa Luxemburg has been burdened with a quadruple resentment: as a woman, as a foreigner, as a Jew and as a cripple.11

Even within the German Communist Party she was dubbed ‘the syphilis of the Comintern’, and Weber once ‘assessed’ Rosa Luxemburg as somebody that ‘[belongs] in a zoo’.12 Dunayevskaya writes:

Virulent male chauvinism permeated the whole party, including both August Bebel, the author of Woman and Socialism – who had created a myth about himself as a veritable feminist – and Karl Kautsky, the main theoretician of the whole International.13

Dunayevskaya’s gender-social analysis also cites a part of a letter in which Victor Adler writes to August Bebel on the subject of Luxemburg:

The poisonous bitch will yet do a lot of damage, all the more so because she is as clever as a monkey [blitzgescheit] while on the other hand her sense of responsibility is totally lacking and her only motive is an almost pervasive desire for self-justification.14

In question was evidently a certain type of conservative political tactics that amounted to attacking prominent women, which in this case included a serious dismissal of Luxemburg’s work based on biology – the fact that she was a woman. Although this important aspect of social and gender history will not be further discussed here, its ubiquity needs to be borne in mind when discussing the theoretical and numerous quasi-theoretical critiques of The Accumulation of Capital and Luxemburg’s experience as a woman theoretician, teacher and revolutionary.

If feminist analyses of Luxemburg’s works in general are rare, even rarer are feminist engagements with her The Accumulation of Capital.15 If there is any interest in feminist interpretation of Luxemburg’s work, it is usually defined in relation to her personal life and occasionally to her theory. Luxemburg not having written much on the subject of the ‘woman question’ certainly contributed to the fact that the subject of most interpretations of Luxemburg’s feminism is linked to episodes from her life and intimacy. These are, naturally enough, highly important subjects, particularly bearing in mind that historical scholarship has traditionally avoided women and their experiences. However, let us try to give an answer to this question: what can a few of Luxemburg’s texts and written speeches tackling the ‘woman question’ tell us about her feminism?

Luxemburg’s Critique of Bourgeois Feminism

Luxemburg did not exclusively devote herself to organising female workers’ groups; her work in that field was obscured by the fact that she usually worked behind the scenes. She fervently supported the organisational work of the socialist women’s movement, understanding the importance and difficulties of work-life for female emancipation. She usually showed her support through cooperation with her close friend Clara Zetkin. In one of her letters to Zetkin we can read how interested and excited she was when it came to the women’s movement: ‘When are you going to write me that big letter about the women’s movement? In fact I beg you for even one little letter!’16 Relating to her interest in the women’s movement, she stated in one of her speeches: ‘I can only marvel at Comrade Zetkin that she ... will still shoulder this work-load’.17 Finally, although rarely acknowledging herself as a feminist, in a letter to Luise Kautsky she wrote: ‘Are you coming for the women’s conference? Just imagine, I have become a feminist!18 Besides the fact that she was working ‘behind the scenes’ and privately showing her interest in the ‘woman question’, she still engaged herself in an open discussion concerning the class problem faced by the women’s movement. In a speech from 1912 entitled ‘Women’s Suffrage and Class Struggle’, Luxemburg criticised bourgeois feminism and assertively pointed out:

Monarchy and women’s lack of rights have become the most important tools of the ruling capitalist class.... If it were a matter of bourgeois ladies voting, the capitalist state could expect nothing but effective support for the reaction. Most of those bourgeois women who act like lionesses in the struggle against ‘male prerogatives’ would trot like docile lambs in the camp of conservative and clerical reaction if they had suffrage.19

The question of women’s suffrage along with the philosophy of the modern concept of law based on the premises of individual rights played an important role in the so-called big transition from feudalism to capitalism. For Rosa Luxemburg, the question of women’s suffrage is a tactical one, as it formalises, in her words, an already-established ‘political maturity’ of proletarian women. She goes on to emphasise that this is not a question of supporting an isolated case of suffrage which is meaningful and completed, but of supporting universal suffrage through which the women’s socialist movement can further develop a strategy for the struggle for emancipation of women and the working class in general. However, the liberal legal strategy of achieving suffrage was not class inclusive and did not aim to overturn the capitalist system. Far from it. For Luxemburg, the metaphysics of individual rights within the framework of a liberal political project primarily serves to protect private ownership and the accumulation of capital. Liberal rights do not arise as a reflection of actual material social conditions, they are merely set up as abstract and nominal, thus rendering their actual implementation or application impossible. As she contemptuously argued: ‘these are merely formalistic rubbish that has been carted out and parroted so often that it no longer retains any practical meaning’.20

Luxemburg rejected the traditional definition of civil rights in every sense, including the struggle for women’s suffrage, and she pointed to its similarity with the struggle for national self determination:

For the historical dialectic has shown that there are no ‘eternal’ truths and that there are no ‘rights’.... In the words of Engels, ‘What is good in the here and now, is an evil somewhere else, and vice versa’ – or, what is right and reasonable under some circumstances becomes nonsense and absurdity under others. Historical materialism has taught us that the real content of these ‘eternal’ truths, rights, and formulae is determined only by the material social conditions of the environment in a given historical epoch.21

What Rosa Luxemburg suggests in the aforementioned quotation from ‘Women’s Suffrage and Class Struggle’ pertains to classical problems initially raised and debated within the framework of socialist feminism from the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century: the role of bourgeois feminism in capitalist reproduction and the use of feminist goals as a means of achieving profit. Whenever capitalism is in crisis or needs ‘allies’ for its restoration or the further accumulation of capital, it integrates marginalised ‘Others’ into its legal liberal political form, be they women, children, non-white races, or LGBTIQ people – whoever is disposable or potentially useful for further commodification:

Thus one of the fundamental conditions for accumulation is a supply of living labour that matches its requirements, and that capital sets in motion.... The progressive increase in variable capital that accompanies accumulation must therefore express itself in the employment of a growing workforce. Yet where does this additional workforce come from?22

According to Luxemburg’s economic theory, the capitalist mode of production reproduces itself by creating surplus-values, the appropriation of which can only be hastened by a concomitant expansion in surplus-creating capitalist production. Hence, it is necessary to ensure that production is reproduced in a larger volume than before, meaning that the expansion of capital is the absolute law governing the survival of any individual capitalist. In The Accumulation of Capital Rosa Luxemburg establishes the premises for understanding capitalism as a social relation which permanently produces crises and necessarily faces objective limits to demand and self-expansion. In this sense she developed a theory of imperialism based on an analysis of the process of social production and accumulation of capital realised via various ‘non-capitalist formations’:

There can be no doubt that the explanation of the economic root of imperialism must especially be derived from and brought into harmony with [a correct understanding of] the laws of capital accumulation, for imperialism on the whole and according to universal empirical observation is nothing other than a specific method of accumulation.… The essence of imperialism consists precisely in the expansion of capital from the old capitalist countries into new regions and the competitive economic and political struggle among those for new areas.23

Unlike Marx, who abstracted the actual accumulation by specific capitalist countries and their relations via external trade, Luxemburg claims that expanded reproduction should not be discussed in the context of an ideal-type capitalist society.24 In order to make the issue of expanded reproduction easier to understand, Marx abstracts foreign trade and examines an isolated nation, to present how surplus-value is realised in an ideal capitalist society dominated by the law of value which is the law of the world-market.25 Luxemburg disagrees with Marx, who analyses value relations in the circulation of social capital and reproduction by disregarding the specific characteristics of the production process which creates commodities. Thus, the market functions ‘totally’, that is, in a general analysis of the capitalist process of circulation we assume that the sale takes place directly, ‘without the intervention of a merchant’.

Marx wishes to demonstrate that a substantial portion of surplus is absorbed by capital as such, instead of concrete individuals. The question is not ‘who’ but ‘what’ consumes surplus commodities. Luxemburg, on the other hand, analyses the accumulation of capital starting from the level of international commodity exchange between capitalist and non-capitalist systems. Despite Luxemburg’s objections, she nevertheless realises that Marx’s analysis of the problem of variable capital serves as the basis for establishing the problem of the law of the accumulation of capital, which is the key to her social-economic theory. Equally, that line of argument allows for understanding the highly important distinction between productive and non productive labour,26 without which it would be almost impossible to understand social-reproduction theory as a specific reaction to neoclassical economics and its partnership with liberal feminism. Precisely for this reason in The Accumulation of Capital Luxemburg quotes Marx:

The laboring population can increase, when previously unproductive workers are transformed into productive ones, or sections of the population who did not work previously, such as women and children, or paupers, are drawn into the production process.27