Art and Value

A version of this interview appeared in French at http://revueperiode.net/la-valeur-de-lart-entretien-avec-dave-beech/

1°) What is the current state of debates around the issues of a marxist approach of artistic production ? Are there different or dominant intellectual currents that can be identified ? On what aspects relate the most important disagreements ?

Marxism has an excellent record of engaging seriously with art and culture. Mostly, however, Marxism, like the rest of aesthetic philosophy, art history and art criticism, has focused its attention on the artwork itself, the experience of artworks and art’s discursive framings rather than artistic production. When Marxists and other leftists have approached artistic production, however, they have done so unfortunately according to one of two misperceived paradigms. Either artistic production is considered to be work or work-like, or it is considered to be the negation of work in an idealised conception of art as nonalienated labour. These two models of thinking are still dominant today among theorists, activists and campaigners. The heyday of the idea that the artist represents a future condition in which work and pleasure will be reconciled has long passed but there are still traces of this in the anti-work movement in which people will be liberated from work and will therefore engage more in cultural activities among other things. At the same time, there is a lot of political work being done today to guarantee wages for cultural work not only by artists but also interns, assistants and art teachers. What all of this lacks, which I have tried to put right in my book Art and Value, is a specific economic analysis of artistic production.

2°) In your book Art and Value. Art's Economic Exceptionalism in Classical, Neoclassical and Marxist Economics (Brill, 2015), you point at the limits of marxist theory concerning the economic analysis of art within capitalism. What are the limits, inconceived dimensions or impasses in current Marxist theory of artistic production ?

My book is in two parts. In the first part I survey the historical record of economics in its discussion and analysis of artworks, and in the second part I begin with an assessment of the record of Marxism – particularly Western Marxism – in its theory of art’s commodification and similar conceptions of art’s incorporation by capitalism, but the rest of the second part of the book is an attempt to reconstruct a Marxist economic analysis of art. In the first part I raise a string of objections to the way that mainstream economics has normalised artistic production as commodity production or focused exclusively on the sale and resale of works of art rather than analysing the economic circumstances under which artworks are produced. So, it is not just the limits of Marxist theory that concerns me in the book, but the failure of mainstream economists and Marxists alike to develop an economics of art based on the specific analysis of the exceptional condition of artistic production. The absence of a Marxist economics of art is only part of this much broader neglect.

3°) What is your own contribution to this Marxist theory ? In other words, what do you propose in your book in order to provide a way out of the current theoretical impasse ? How do you renew the discussion about art's production and specific economy within capitalist system ?

I have confronted the Marxist theory of art’s commodification and related theories of art’s incorporation in the culture industry and art’s participation in the Spectacle. My chief claim is that the various theories of art’s capture by capitalism ought to be proved through economic analysis rather than merely asserted theoretically, assumed as a corollary of the argument that capitalism has subsumed all life, or derived from a sociological analysis of the art as a luxury market. Of course, I’ve also provided the outlines of what I think is an adequate economic analysis of art that focuses on art’s mode of production rather than focusing exclusively on transactions within the art market. While the art market appears to be a typical capitalist operation, an analysis of artistic labour suggests a graphically different assessment of the relationship between art and capitalism. The principle feature of art as a mode of production is that artists have not been converted into wage-labourers as is necessary for the capitalist mode of production.

Western Marxism has since the 1930s has been characterised by factional debate, but one thing that has gone almost completely unchallenged is the thesis that art has been commodified. The art market is a very substantial global trading operation and so, if you measure commodification by the presence of markets in certain goods, then the argument for art’s commodification appears to be a safe bet. Once this is established it is a short step to more expansive theories of reification, culture industry, spectacle, real subsumption and so forth, in which it is not only the objects of cultural production that are commodified but also the subjects who experience them. However, I argue that Marx’s analysis of the transition to capitalist commodity production does not turn on the transformation of modes of distribution, circulation and consumption but to the social relations of production. Moishe Postone, Michael Heinrich and Peter Hudis make this argument better than I do but my contribution to Marxist theory on this score, I would say, is that I not only apply the theory of capitalist production to artistic production but demonstrate that, despite the buying and selling of artworks, artistic production was never fully converted to capitalist commodity production and therefore artworks are not, strictly speaking, commodities at all in the capitalist sense.

4°) You have some disagreements with Christian Fuchs' theories about digital labour and digital cultural commodities

Prisons and Class Warfare

A version of this interview appeared in French at http://revueperiode.net/le-role-de-la-prison-dans-la-lutte-des-classes-entretien-avec-ruth-w-gilmore/

Clément Petitjean: In Golden Gulag, you analyse the build-up of California's prison system, which you call “the biggest in the history of the world”. Between 1980 and 2007, you explain that the number of people behind bars increased more than 450%. What were the various factors that combined to cause the expansion of that system? What were the various forces that built up the prison industrial complex in California and in the US?

Ruth Wilson Gilmore: Sure. Let me say a couple of things. I actually found that description of the biggest prison building project in the history of the world in a report that was written by somebody whom the state of California contracted to analyse the system that had been on a steady growth trajectory since the late 1980s. So it's not even my claim, it's how they themselves described what they were doing. What happened is that the state of California, which is, and was, an incredibly huge and diverse economy, went through a series of crises. And those crises produced all kinds of surpluses. It produced surpluses of workers, who were laid off from certain kinds of occupations, especially in manufacturing, not exclusively but notably. It produced surpluses of land. Because the use of land, especially but not exclusively in agriculture, changed over time, with the consolidation of ownership and the abandoning of certain types of land and land-use. It also produced surpluses of finance capital – and this is one of the more contentious points that I do argue, to deadly exhaustion. While it might appear, looking globally, that the concept of surplus finance capital seemed absurd in the early 1980s, if you look locally and see how especially investment bankers who specialised in municipal finance (selling debt to states) were struggling to remake markets, then we can see a surplus at hand. And then the final surplus, which is kind of theoretical, conjectural, is a surplus of state capacity. By that I mean that the California state’s institutions and reach had developed over a good deal of the 20th century, but especially from the beginning of the Second World War onwards. It had become incredibly complex to do certain things with fiscal and bureaucratic capacities. Those capacities weren't invented out of whole cloth, they came out of the Progressive Era, at the turn of the 20th century. In the postwar period they enabled California to do certain things that would more or less guarantee the capacity of capital to squeeze value from labour and land. Those capacities endured, even if the demand for them did not. And so what I argue in my book is that the state of California reconfigured those capacities, and they underlay the ability to build and staff and manage prison after prison after prison. That's not the only use they made of those capacities once used for various kinds of welfare provision, but it was a huge use. And so the prison system went from being a fairly small part of the entire state infrastructure to the major employer in the state government.

So the reason that I approached the problem the way I did is because I'm a good Marxist and I wanted to look at factors of production, but also to make it very clear – and this has to do with being a good Marxist – that these factors of mass incarceration, or factors of production, didn't have to be organised the way they were. They could have become something else. Therefore I begin with the premise that prison expansion was not just a response to an allegedly self-explanatory, free-floating thing called crime, which suddenly just erupted as a nightmare in communities. And indeed, in order to think about crime and its central role in California's incarceration system, I studied, like anybody could have, what was happening with crime in the late 1970s and early 1980s. And not surprisingly, it had been going down. Everybody knew it. It was on front pages of newspapers that people read in the early 1980s, it was on TV, it was on the radio. So if crime did not cause prison expansion, what did?

CP: So what was happening more specifically in California? How did those surpluses come together to create this mass prison system?

RWG: Well, they came together politically. In a variety of ways. During the 1970s, the entire US economy had gone through a very long recession. It was the time when the US lost the Vietnam war, when stagflation became a rule rather than an unimaginable exception -- which is to say there was both high unemployment and high inflation. In that context, throughout the United States, people who were in prison had been fighting through the federal court system concerning the conditions of their confinement, the kinds of sentences that they were serving, and so forth. Many of these lawsuits were brought by prisoners on their own behalf. They slowly made their way through the courts. Eventually, in California but in many other states too, in the late 1960s and again in the mid-1970s, the federal courts told the state prison system: "Do something about this, because you're in violation of the Constitution." At first it might seem that the Vietnam War, stagflation and the violation of prisoners’ constitutional rights are unrelated. But indirectly, building prisons and using crime became a default strategy to legitimise the state that had become seriously delegitimised due to political, military, and economic crises. Prison expansion became a way for people in both political parties to say: "The problem with the United States is there is too much government. The state is too big. And the reason people are suffering from this general economic misfortune is because too much goes to taxes, too much goes to doing things that people really should take care of on their own. But if you elect us, we will get rid of this incredible burden on you. There is something legitimate we can do with state power, however, which is why you should elect us: we will protect you from crime, we will protect you from external threats." And people were elected and re-elected on the basis of these arguments. Again, even though everybody knew that crime was not a problem. It's pretty astonishing to me. I lived through this period and went back and studied it later. I found in the California case -- and I currently have students who are studying other states -- we keep coming across similar patterns: economic crisis, federal court orders, struggles over expansion, increased role of municipal finance in the scheme of prison expansion.

In California, people who had come up through the civil service, working in the welfare department, or working in the department of health and human services, eventually were recruited to work on the prison side because they had the skills to manage large-scale projects designed to deliver services to individuals. And they brought their fiscal and bureaucratic capacities over to the prison agency in order to help it expand and consolidate. We actually see the abandonment of one set of public mandates in favour of another – of social welfare for domestic warfare, if you will. And I can't say, nor should anybody, that the reason all this happened was because of a few people who had bad intentions distorted the system. But rather we can see a systemic renovation in the direction of mass incarceration: starting in the late 1970s, when Jerry Brown, a Democrat, was governor of California, as he is now; then taking off enormously in the 1980s under Republican regimes; but never going down. It didn't make any difference which party was in power. And the prison population did not begin to go down until elaborate and broad-based organising combined with a long-term federal court case (again!) compelled system shrinkage in the last several years.

CP: In the book, you argue that prisons are “catchall solutions to social problems.” Would you say that the rise of the prison industrial complex illustrates, or means, deep transformations of the American state, and marks the dawn of a new historical period for capitalism, one where incarceration would be not only the legitimate but the only way of dealing with surplus populations?

RWG: Honestly, fifteen years ago, I would have said yes. Now, I say "pretty much, but not absolutely yes". Because it's almost worse than the way you framed the question. Rather than mass incarceration being a catchall solution to social problems, as I put it, what has happened is that that legitimising force, which made prison systems so big in the first place, has increasingly given police – including border police -- incredible amounts of power. What has happened is that certain types of social welfare agencies, like education, income support, or social housing, have absorbed some of the surveillance and punishment missions of the police and the prison system. For example in Los Angeles, a relatively new project, about ten years old, focuses on people who live in social housing projects. Their experience has been shaped by intensive policing, criminalization, incarceration and being killed by the police. Under the new project they have opportunities for health, tutoring for children, all kinds of social welfare benefits if and only if they cooperate with the police. In the book Policing the Planet, my partner and I wrote a chapter that goes into rather exhaustive details about that case.

CP: Would you say that those shifts herald a new historical period for capitalism?

RWG: This is a tough question, as you know, for a bunch of reasons. One is that we've all learned to lisp: everybody used to say "globalisation," now it’s "neoliberalism," and people are more or less talking about the same thing. My major mentor in the study of capitalism is the late great Cedric Robinson, who wrote an astonishing series of books, but the one that completely changed my consciousness is Black Marxism. Robinson argues that capitalism has always been, wherever it originated (let's say rural England), a racial system. So it didn't need Black people to become racial. It was already racial between people all of whose descendants might have become white. Understanding capitalism this way is very productive for me when thinking about the present. One issue is what's happening with racial capitalism on a world scale. A second issue has to do with particular political economies, especially those that are not sovereign, like the state of California: how does political-economic activity re-form in the context of globalisation’s pushes and pulls? Certainly, California's economy continues to be big. It moves up and down a little bit, but if it were a country, it would be in the top seven largest economies. However, the mix of manufacturing, service and other sectors has changed over time. There's still a lot of manufacturing in the state, although it tends to be more value-added, lower-wage manufacturing, sweatshops and so forth. And far less steel, and producer goods, and consumer durables.

How, then, should we analyse in order to organise in places like California, New York, Texas, with their various and variously diverse economies, characterised by organised abandonment and organised violence? How can we generalize from the racist prison system to a more supple perception of racial capitalism at work, to understand and intervene in places where states no less than firms are constantly trying to figure out how to spread capital across the productive landscape in ways that will return profits to investors as quickly as possible? The state keeps stepping in while pretending it's not there. And here I’m not talking about private prisons, which are an infinitesimal part of mass incarceration in the US, nor of exploited prisoner labour, which also doesn’t explain much about the system’s size or durability (which, as we’ve already seen, is vulnerable). Rather, I am talking about how unions that represent low to moderate wage public sector workers, which have a high concentration of people of colour as current and potential members, might join forces with environmental justice organisations, biological diversity/anti-climate change organisations, immigrants’ rights organisations, and others to fight on a number of fronts group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death -- which is what in my view racism is. And if that’s what racism is, and capitalism is from its origins already racial, then that means a comprehensive politics encompassing working and workless vulnerable people and places becomes a robust class politics that neither begins from nor excludes narrower views of who or what the “working class” is.

CP: In the book, you develop a critical perspective strongly influenced by David Harvey's critical geography. What does this perspective reveal specifically about mass incarceration?

RWG: I became a geographer when I was in my 40s because it seemed to me, at least in the context of US graduate education, it was the best way to pursue serious materialist analysis. There are so few geography PhD programs in the United States. And I'd been thinking that I was going to train in planning because it seemed the closest to what I wanted to do: to put together “who”, “how,” and “where” in a way that did not float above the surface of the earth but rather articulated with the changing earth. I actually stumbled into geography. I happened to come across Neil Smith at a Rethinking Marxism conference and was really taken by his work; not only had I not thought about geography, I hadn’t taken a geography course for three decades, since I was 13. So at the last minute, instead of mailing my application to the planning department at Rutgers, I mailed it to the geography department. And the rest is kind of history. Enrolling in geography brought me into the world of Harvey’s historical geographic materialist way of analysing the world. I took very seriously what I learned from David, what I learned from Neil and a few other people, and tried to build on it, having already had a long informal education with people like Cedric Robinson, Sid Lemelle, Mike Davis, Margaret Prescod, Barbara Smith, Angela Davis, and many others. And I think that had I not been trained in geography, or beguiled by geography, maybe, I would not have thought as hard as I did about, for example, urban-rural connections – their co-constitutive interdependencies. And I know I wouldn't have thought in terms of scale -- not scales in the sense of size, but in terms of the socio-spatial forms through which we live and organise our lives, and how we struggle to compete and cooperate. And I certainly would not have conceptualised mass incarceration as the "prison fix" had I not read David's Limits to Capital and thought about the spatial fix as hard as I could. We're colleagues, now, David and I. We enjoy working together and debating toward the goal of movement rather than having the last word.

CP: Can you elaborate on what you mean by "prison fix" compared to Harvey's "spatial fix"?

RWG: What I mean in my book is that the state of California used prison expansion provisionally to fix – to remedy as well as to set firmly into space – the crises of land, labour, finance capital and state capacity. By absorbing people, issuing public debt with no public promise to pay it down, and using up land taken out of extractive production, the state also put to work, as I suggested earlier, many of its fiscal and organisational abilities without facing the challenges that were already mounting when the same factors of production were petitioned for, say, a new university. The prison fix of course opened an entire new round of crises, just as the spatial fix in Harvey displaces but does not resolve the problem that gave rise to it. So in the case of communities where imprisoned people come from, we have the removal of people, the removal of earning power, the removal of household and community camaraderie, you name it – all of that happened with mass incarceration. In the rural areas where prisons arose we can chart related de-stabilisations: rather than, as many imagine, rural prison towns acquiring resources displaced from urban neighbourhoods, the fact is the two locations are joined in a constant churn of unacknowledged though shared precarious desperation – which was the basis on which some of the organising I described above took form. In other words infrastructure materially symbolised by the actual prison indicates the extensively visible and invisible infrastructure that connects the prison and its location by way of the courts and the police, the roads for families to visit and goods and incarcerated people to travel, back to the communities of origin expansively incorporating the entire intervening landscape. One of the things I tried to do in the book, framing it with two bus rides, was to give people a way of thinking about what I’ve just said that’s more viscerally poignant. Thinking about the movement across space and the movement through space gives us some sense of the production of space.

The purpose of Golden Gulag was not to make people say "Oh my God, we've all been defeated!" but rather to say "Wow, that was really big, and now I can see all the pieces. So perhaps instead of thinking there's nothing to be done, what I recognise is there's a hundred different things that we could do. We can organise with labour unions, we can organise with environmental justice activists, we can organise urban-rural coalitions, we can organise public sector employees, we can organise low-wage, high-value-added workers, who are vulnerable to criminalisation. We can organise with immigrants. We can do all of these things, because all of these things are part of mass incarceration." And we did all that organising!

CP: That's a perfect transition to another set of questions about organising against mass incarceration. Are there resistance movements within prisons comparable to what happened in the 1970s, with the 1971 Attica uprising for instance?

My area of expertise doesn't happen to be on that. Orisanmi Burton is someone who is doing fantastic research on that question. Of course, one of the things that's happened in California prisons, particularly the prisons for men, is that their physical design, as well as the design of their management system, were deliberately aimed by the Department of Corrections, starting in the late 1970s, to undermine the possibility of the kind of organising that had characterised the period from the early 1960s to the mid-1970s. Especially the ones called 180s, or level 4: those are the high-security prisons. They're not panopticons, but prisoners can't evade being under surveillance. There have been not only automatic lockdowns, but also the reduction of education and other in-prison programs, even places where people in prison can gather, such as day rooms, classrooms, gyms, places where prisoners could do the time with some however modest ongoing sense of self. All of the design changes were intended to undermine prisoner organising and solidarity.

One hugely notorious thing that happened in the California system in particular in the late 1970s, that may or may not have happened in other systems, is that the Department of Corrections, was experimenting with ways to keep prisoners from developing solidarity with each other and against the guards. In the early 1970s, California prisoners had notoriously declared "Every time a guard kills one of us, we're going to kill one of them until they stop killing us." And there were seven incidents over some years. A guard killed a prisoner, prisoners killed a guard. Not necessarily the guard who killed the prisoner, but somebody died because somebody died. So the department, right before its big expansion began, was trying to figure out what to do. And it came up, not surprisingly, with a solution that was designed to foster inter-prisoner distrust. The managers declared that certain categories of prisoners belonged to certain ethnic or regional gangs, and then fomented discord between the gangs. In a time when desegregation was becoming the law of the land, the Department of Corrections started segregating people in prisons according to the gangs and then to racial and ethnic groups. This is all well documented, there are case files and lawsuits, and an incredible archive, still to be thoroughly read and written about. And there were countless hearings about this practice throughout the 1990s. I sat through hours of testimony, in which the Department insisted, and has until this day: "No, we were just responding to what objectively existed." Whereas others who testified, including former prison wardens, said: "No, this didn't exist: you made it. You created it."

What the Department “created” led to development of something called the Security Housing Unit (SHU), which is effectively a prison within the prison. The first one in California opened in 1988 and the second in 1989. In the latter, called Pelican Bay State Prison, people in the SHU had staged several hunger strikes beginning in 2013. And some of the people in that unit, segregated according to their alleged gang affiliation, some of whom had been in that prison within the prison for more than twenty years, had accepted and projected the rigid ethnic, racial, and regional differences as meaningful and immutably real. But as they were trying, as individuals, to sort out a way for them to get out of the prison in the prison and go back to the general prison population, they became increasingly aware of what had happened historically, a dire reform of which they were the current expression. And so in recent years, these people in four “gangs” eventually declared that the only way to solve the problem inside was, to use their word, to end the hostility between the races. Which is an astonishing thing. I've been inside a lot of prisons, including Pelican Bay. And the transformation of consciousness from what I learned from interviewing people in prisons for men about their conditions of confinement in the early 2000s compared with the organising and analysis that emerged in the last five or so years is astonishing.

I also want to add something about the prisons for women. In the prisons for women, the level of segregation was never as high -- to the extent, for example, that they had not separated out people who were doing life on murder and people who were doing a year on drugs. Whereas in a prison for men people are segregated according to custody level (what they are serving time for having done) plus segregated in a number of other ways including race and ethnicity. And so, in part because of the social and spatial organisation of the prisons in the period that featured the crackdown on organising in prisons for me, there was a high and growing level of organising among the people in prisons for women. So during the last fourteen or fifteen years, as the state of California was trying to build fancy new so-called “gender responsive” prisons for women – to allow mothers to be locked up with their kids, for example -- people inside those prisons, however they identified in terms of gender, wrote and signed "Don't do this for us, because that's just going to expand capacity to lock people up. It's not going to make our lives better." Three thousand people did that organising in prisons for women, and their self-determination and bravery occurred at great personal risk to themselves because locked-up activists are wholly at the mercy of guards and prison managers.

CP: What about the organising outside of the prisons? And in particular in communities directly affected by mass incarceration?

RWG: The organising outside has been quite rich and varied over the years. In my experience, some of which I write about in a new chapter to the upcoming second edition of Golden Gulag, people who at the outset started doing work on behalf of one person in their family or even maybe two people in their family, thinking this was an individual, or greatest scale, household problem, came to understand through their experiences -- working with others, mostly women, most of whom were mothers -- the political dimensions of what they originally encountered as a personal, individual, and legal problem. That's one kind of organising that has persisted for many years now, 25 years of more. There's also the organising that we, meaning the groups Critical Resistance and California Prison Moratorium Project, helped to foster between urban and rural communities, under a variety of nominal issues which I described earlier: biological diversity (we took up on behalf of the lowly Tipton kangaroo rat) but also environmental justice (air quality, water quality for instance). We managed to develop and wage campaigns bringing people together across diverse issues and diverse communities in rural and urban California, so that they could recognise each other as probable comrades rather than presumed antagonists. And that has happened over and over again.

Going back to the fact that the number of people in prisons in California has gone down in recent years: the public explanations for that, the superficial or above-the-surface explanation, is that in 2011 the state of California lost yet another lawsuit, Brown v. Plata, also called “Plata/Coleman,” and was ordered to reduce the number of people held in the Department of Corrections’ physical plant (33 prisons plus many camps and other lockups). The federal lawsuit demonstrated that approximately one person in prison a week was dying of an easily remediable illness because of medical neglect. During the two decades between the beginning of the legal campaign and its resolution, some of the original litigants had long since died. Ultimately, the right-wing Supreme Court of the United States (the court that handed George W. Bush the presidency in the year 2000) could not deny the evidence. There were just too many bodies. In its final judgment that court agreed with lower court rulings, affirming that California could not build its way out of its problem.

But the question that few people who have followed this story ever asked themselves is "How come California, that had been opening a prison a year for 23 years, suddenly slowed down to almost a halt and only opened one prison between 1999 and 2011? And the answer is all that grassroots organising that I described earlier. We stopped them building new prisons. We made it too difficult. And we showed in our campaigning that whenever the department built a new prison, allegedly to ease crowding, the number of people in prison jumped higher than the new buildings could hold. The new relationships on the ground, organised by prison abolitionists – though the vast majority of participants themselves were not necessarily abolitionist – compelled these courts, who had never summoned any of us as serious witnesses for anything, to say that California could not build its way out of its problem and that it had to do something else. So now a lot of anti physical plant expansion activity in California has shifted to jails, not prisons. (Jail is where someone is held pending trial or if their sentence is only a year or less. Prison is where someone is sent to serve a sentence for a year and a day or more.) The jails are now expanding because once California complied with the Supreme Court ruling, the state, in order to reduce the number of people it locks up, made resources available to the lower political jurisdictions -- the counties -- to do whatever they wanted in exchange for retaining people convicted of certain crimes locally rather than sending them to state custody. (This adjustment is called “realignment.”) The counties could have taken those resources and said to convicted people "Go home and behave yourselves.” They could have taken the resources and changed guidelines for prosecutors so there would be fewer convictions. They could have put the resources into schools or healthcare or housing. But – and this gets back to the nagging question of state capacity and legitimacy -- a little more than half of the state’s 58 counties have thus far decided to build new jails. And then we see in reverse the phenomenon I discussed earlier, about welfare state agencies absorbing surveillance and punishment agencies. The sheriffs, who run the jails, now insist that they need more and bigger jails for reasons of health: "We have to supply mental health care and counseling to troubled people. We need to deliver social goods, and the only way we can do it is if we can lock people up." So the new front is fighting against “jails-instead-of-clinics,” “jails-instead-of-schools,” and so on. The work brings new social actors into the mix, and, as we discussed earlier, it enables the broadest possible identification of purpose in class terms.

To give you a few other examples of the kinds of solidarity that we managed to bring into action over time in California, there was a prison that was supposed to have opened in 2000 but we slowed it down. We didn't manage to stop it, but as I said, after opening a prison a year up to 1998, there were none opened between 1999 and 2005. That prison was scheduled for construction by a member of the Democratic party who had just been elected governor, and he was paying back the guards' union, who had given him almost a million dollars to help with his campaign. So then we got busy and organised as many different ways as we could. And one of the ways we could organise, it turned out, was with the California state employees association, which is part of an enormous public sector union in California. And they represent all kinds of workers in the prisons except the guards, because the guards have their own stand-alone union. And much to our surprise, the members of state employees union were willing to go up against the guards and oppose that prison. When they finally agreed to meet with the abolitionists they said: "Look. The guards get whatever they want. What we do, as secretaries, school teachers, locksmiths, drivers, mechanics gets squeezed more and more. We see the lives of the people in custody getting worse and worse, with no hope for getting back to a normal life when they get out -- as most people do. And the union that we're part of represents people who work in the public sector, in housing, healthcare, so on and so forth, in the cities and counties as well as at the state. So if we recognise who our membership is and what they do, there's no reason for us to support this prison. Even if we might lose a few members who would have the jobs in the new prison, there’s more to our remit, as a public sector union.” That completely surprised me, and for a heady political moment we had half a million people throughout California calling for a prison moratorium. It's hard to keep those kinds of political openings lively, but it lasted long enough to interrupt the relentless schedule that the prisons in California had been on since the early 1980s.

CP: From an outsider’s perspective it seems that the Black Lives Matter movement gave a new impetus to debates around prison abolition in radical circles. What does it say about the history of the abolition movement? What's the current balance of forces? What do strategic debates look like?

It’s true that #Black Lives Matter has got people thinking about and using the word "abolition". That said, the abolition that they have helped put into common usage is more about the police and less about the prisons. Although of course there is a connection between the two. It’s been amazing to me and many of my comrades to see left liberal politicians, or magazines like The Nation or Rolling Stone, seriously ask whether it is time to abolish the police. The ensuing debates tend to be the obvious ones: insofar as abolition is imagined only to be absence – overnight erasure – the kneejerk response is “that's not possible”. But the failure of imagination rests in missing the fact that abolition isn’t just absence. As W.E.B. Du Bois showed in Black Reconstruction in America, abolition is a fleshly and material presence of social life lived differently. Of course, that means many who are abolition-friendly falter at what the practice is. All the organising I’ve described in our conversation is abolition – not a prelude, but the practice itself. There was a recent attack on abolitionists by some historian who decided, without studying, that abolitionists are a deranged theology. He knew a little, for example, about the Brown v. Plata case, but zero about the on-the-ground moratorium organising that realised the Plata/Coleman theory (“overcrowding”) as sufficient cause for which the remedy would not be more of the same. Abolition is: figuring out how to work with people to make something rather than figuring out how to erase something. Du Bois shows, in exhaustive detail, both how slavery ended through the actions and organised activity of the slaves no less than the Union Army, and, since slavery ending one day doesn't tell you anything about the next day, what the next day, and days thereafter, looked like during the revolutionary period of radical Reconstruction. Abolition is a theory of change, it's a theory of social life. It's about making things.

CP: What does the central role of mass incarceration in maintaining the status quo imply in terms of class struggle strategies? Do anti-incarceration struggle and abolition organising play a more strategic role today?

RWG: Here's a way of thinking about that in the US context. In the United States today, there are about 70 million adults who have some kind of criminal conviction -- whether or not they were ever locked up -- that prohibits them from holding certain kinds of jobs, in many types of jobs. In other words, it doesn't make any difference what you allegedly did: if you've been convicted of something, you can't have a job. So just take a step back and think about that for a second, just in terms of sheer numbers. If we add the number of people who are effectively documented not to work, with the additional 7 or 8 million migrants who are not documented to work, the sum equals about 50 percent of the US labour force — mostly people of colour, but also 1/3 white. Half the US labour force. So it seems that anti-criminalisation and the extensive and intensive forces and effects of criminalisation and perpetual punishment has to be central to any kind of political, economic change that benefits working people and their communities, or benefits poor people, whether or not they're working, and their communities. This should be a given, but often it's not. In part that’s because "mass incarceration" has, unfortunately but for understandable reasons, come to stand in for "this is the terrible thing that happened to Black people in the United States." It is a terrible thing that happens to Black people in the United States! It happens also to brown people, red people … and a whole lot of white people. And insofar as ending mass incarceration becomes understood as something that only Black people must struggle for because it's something that only Black people experience, the necessary connection to be drawn from mass incarceration to the entire organisation of capitalist space today falls out of the picture. What remains in the picture seems like it’s only an anomalous wrong that seems remediable within the logic of capitalist reform. That's a huge impediment, I think, for the kind of organising that ought to come out of the various experiments in worker and community organising that can produce big changes. Everything is difficult in the US right now, for all the obvious reasons I won’t waste space on now. That said, I look with hope for all indications of ways to shift the debate and organising. The answer for me is to consider in all possible ways how the preponderance of vulnerable people in the US and beyond come to recognise each other in terms not just of characteristics or interest, but more to the abolitionist point and purpose.

Karl Marx’s Mathematical Return

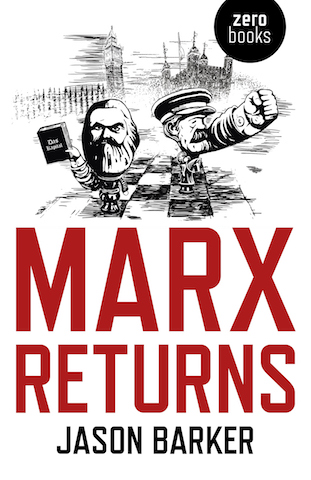

Chris Rumble reviews Marx Returns by Jason Barker (2018, Zero Books). Following several disappointing portrayals, a new novel by the author and filmmaker takes an ingenious look at why Karl Marx might have been right after all.

The Thinker and the Militant

Rationality, Islam, and Decolonisation with Maxime Rodinson

By Selim Nadi. Translated by Joe Hayns.

This piece was originally published in Revue Période: http://revueperiode.net/le-savant-et-le-militant-rationalite-islam-et-decolonisation-chez-maxime-rodinson/

Selim Nadi is a French PhD Student and a member of the editorial board of the French journals Période andContretemps.

Joe Hayns would like to thank Ian Birchall, Selim Nadi, and Maïa Pal for their help and encouragement. All mistakes are his. You can follow him @JoeHayns

The outstanding intellectual Maxime Rodinson is known above all for his magisterial study, Islam and Capitalism (1966), and for his intense militant activity, notably with the Parti Communiste Français (PCF), of which he was a member from 1937 to 1958. In this article, Selim Nadi addresses the relations between Rodinson’s scientific work and political engagement, through an appraisal of Rodinson’s analyses of the tactical and strategic possibilities that Islam offered to anti-colonial struggles. From the Algerian national liberation struggle, to the dialogue between Rodinson and Edward Said, to the Iranian Revolution, this article revisits the challenges faced by Rodinson in his efforts to think through and work with revolutionary processes in the Muslim countries.

I have always perceived a certain contradiction between political engagement and rationality […] Experience and age help. I’ve realised that the more our activism advances, the more one sees, in each instance, that irrationalities drag on practical currents. (Maxime Rodinson, Entre Islam et Occident. Entretiens avec Gérard D. Khoury [Between Islam and the West. Interviews with Gérard D. Khoury.])

It was in 1957, when he was 23 years old, that Mohamed Harbi - then member of the Algerian FLN – met Maxime Rodinson (1915-2004) for the first time. Harbi was already familiar with the works and interests of Rodinson. In an interview with Sébastien Boussois, Harbi explained that at that time, those researching the Arab countries were typically Islamologists who conferred an absolute role to religion, making it the Alpha and Omega of their analyses. Hence, according to Harbi, the principal ‘radical scholars’ (‘contre-universitaires’) of the time for the students and militants were Claude Cahen (1909-1991) and Maxime Rodinson. Harbi was like all his comrades interested not only in Maghrebin societies, but more generally in the ensemble of the Middle East, his studies helped by an exceptional linguistic ability.

When Rodinson met Harbi, his position vis-à-vis the PCF, which he would quit two years later, was already critical. After his departure in 1958, Rodinson took more and more distance from political militancy, whilst remaining firmly convinced that Marxism proposed the most pertinent methodology for analysing non-European societies, notably for those colonised or previously colonised countries. It’s this aspect of Rodinson’s political thought that will most interest us here: his theorisation of anti-colonialism – and, in particular, his reflection on the strategic role Islam could play as an instrument of mobilisation. It seems that, beyond the colonial question itself, this aspect of Rodinson’s thought allows us to return to what he named an ‘independent Marxism’, in his response to a question from Egyptian sociologist Ibrahim Sa’ad ad-Din, during a conference in Cairo, in 1969. Since an ‘independent Marxism’ should not be confounded with a sort of ‘academic neutrality,’ it is interesting to consider what this approach contributes to Rodinson's analysis – notably, during his dialogues with militants, like Amar Ouzegane, or intellectuals, like Edward Said. This should be done without attempting to mask the limitations of this ‘independence’, which was accompanied by Rodinson’s distancing from any organisational engagement, albeit without his ever falling into an apolitical neutralism.

An erudite polyglot of the first order, Rodinson published a number of works that became authoritative far beyond Marxist social scientist circles. Having published translations of Arabic and also Turkish, and taught Ethiopian and Old South Arabian, and as capable of writing on the poetry of Nazim Hikmet as on Arab cuisine, Rodinson published a number of foundational texts on linguistics (on the incompatibility of consonants in Semitic language root words, for example), and on the emergence of capitalism in Muslim countries (his work Islam and Capitalism remains without doubt his most known and discussed work) and, too, on the historical evolution of anti-Semitism, without counting his many reviews of works. Such erudition seems extraordinary, in the literal sense of the term, in the current context. But, Rodinson was also a political militant, a long-time member of the PCF, raised in a strongly politicised family (his father had, perhaps, played chess with Trotsky). In his memoirs, Rodinson recalled that he’d attended his first demonstration with his mother in 1927, following the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. From that moment, Rodinson never stopped having one foot in the sphere of militancy. It would seem, nonetheless, that throughout his lifework, he more and more took distance from the militant world, without ever depoliticizing either. Nor was he sparing in analysing the international situation, for example during the Gulf War of 1991. Rodinson was constantly gripped by the need forscientificité andrationalité.

It seems essential then for us to inquire into his analysis of tactical and strategic questions, especially into an element that was impossible to ignore in the revolutionary processes dynamising the ‘Third World’: the powerful tactical power offered by Islam for mobilising the masses against colonialism and imperialism. The present article explores Rodinson’s debates with militants and intellectuals, as well as some texts that were - rather than mere reactions to burning questions - imposed by circumstance and that dwelt over first-order strategic problems.

On Rodinson, Pierre Vidal-Naquet wrote that ‘not only was he a man with a great library - he read and interpreted the books he possessed. He was the greatest érudit that I ever encountered’ [1]. It is essential we discover, or rediscover, thisérudit, through restoring his thought in the debates and political issues of the second half of the 20th century.

Islam and the ‘psychology of the masses’

The ideal is not remote, situated in another world; it is produced by earthly transformations. But, it requires the total devotion of the individual. As with Mazdeism, every thought, every word spoken, and every action has a cosmic value. It builds, on the earth, the Bonne Cité (the Good City). This had been, for Ouzegane, theCité Communiste, interlinked with the international communist movement; it is now, for him, the Algerian Muslim Cité, with a socialist structure. The national addition, secondary and largely insignificant in the first ideology, has become primordial. (Maxime Rodinson, 'From Communism to the FLN’)

In his study of French anti-colonialism since the 16th century [2], historian Claude Liauzu explained that, during the Algerian revolution, the religious factor was largely underestimated by the French anti-colonialists, who principally perceived Algeria through the eyes of their laïcs (secular) Arab comrades. It was in this context that Rodinson appeared clearly as a dissonant voice, for his thinking that the Muslim religion’s imbrication in social and political relations was a key element of anti-colonial struggles in Muslim countries. Rodinson never searched for an ideal-type of anti-colonial militant, revolutionary andlaïc, but rather always began with the necessity of analysing actually existing society, rather than building a political analysis on an imagined social reality. The role that Rodinson confers on Islam in the anti-colonial struggles stands out especially in his dialogue with Amar Ouzegane (1910-1981). Ouzegane, an Algerian militant, was counted amongst the founders in 1936 of the Parti Communiste Algérien (PCA), before being excluded for ‘nationalist deviances’ in 1947. In a review, published inLeMonde Diplomatique in 1962 (and re-published inMarxisme et monde musulman) of Ouzegane’s book,Le meilleur des combats (The Best Battle) - in which Ouzegane lengthily responded to a 1960 text of Larbi Bouhali, who’d succeeded him at the PCA secretariat – Rodinson discussed the strategic role that Islam might play as a political instrument. In his book, Ouzegane did not invoke any theological argument to explain the importance of Islam in the context of revolutionary Algeria, but did, though, very much insist on the social role played by the Muslim religion. In his review, Rodinson cites Robespierre’s appraising of atheism as an ‘aristocratic’ phenomenon during the French Revolution in order to comment on Ouzegane’s claim that atheism was a kind of marker of the French labour aristocracy [3]. However, despite Rodinson having had a sincere political sympathy for Ouzegane, he remained no less critical of the role that religion can play as a political instrument and tactic.

Whilst Rodinson is largely known for his study of the development of capitalist in the Muslim countries, he was equally interested, in a profound way, in the ‘use’ that Islam might be put to towards non-religious ends – especially, the role that the Muslim religion might play in independence struggles. As Rodinson wrote, in an article published in the Partisans journal in 1963, the leaders of national liberation struggles, whether they were atheists or not, should not ignore the potential to mobilise the masses that religion offered. In the case of the Muslim countries, for example, it was clear that religious oppression played a central role in national oppression. In the article, Rodinson again mobilised Ouzegane’s point of being less concerned about whether Muslim dogmas were true or false, than with seeing Islam principally as a social and political instrument. Thus – and it was on precisely this point that Rodinson made his critique – according to Ouzegane, militant atheists were not necessarily mistaken in the worldview, but rather in the mis-comprehension of the ‘social psychology’ of the Algerian masses. Rodinson considered Islam as neither a good nor a bad ideology a priori, but rather insisted on the need to produce analyses of the religion that account for its social conditions in which it developed. As he wrote at the beginning of the his book De Pythagore à Lénine, ‘the best way to comprehend nothing of a phenomenon is to isolate it, and to consider it, from either the interior or the exterior, as if it is the only one of its type’ [4].

Nevertheless, in the case of the national liberation struggles, Rodinson was fairly sceptical of the utilisation of Islam as a primary 'mobilisation tool'; indeed, he considered such an approach to the religious question as potentially dangerous for the newly independent states, and rejected the concept of the 'social psychology' of the masses mobilised by Ouzegane. According to Rodinson, the danger resided in that, 'pushed to the limit by some peasant' - a politician like Ouzegane, for example, who later became a minister in the newly independent Algeria:

would have to confess to believe the same thing as him. Maybe, by mental restriction, he would decide that he himself does not believe in what are, for the modern, rational spirit, the most shocking aspects of the peasant’s faith, for example believing in the mare of Borâq [a Pegasus with a woman’s head - Ed. Note]. But, he would have dispossessed himself of the right of critiquing these aspects. Practically, he would align himself with the peasant’s faith. What’s the import, one might say, of this half-spoken alignment, if the peasant is convinced to construct socialism, suffering and sacrificing, albeit whilst believing in following the precepts of Allah and of the Prophet Mohammed? We’ve sacrificed so many things for the revolution, among others, the search for the truth in its various guises. Why not go all the way? [5]

Rodinson would write something similar some years later, at the end of his classic work, Islam and Capitalism, on the subject of the attachment of the Algerian poor to Islam, and the potential consequences of its political instrumentalisation:

It must be seen that this attachment, before it being an expression of faith, and although it may indeed lead many souls towards values that are strictly religious in character, is nonetheless fundamentally a national, and a class, phenomenon. The poor see in Islam that which distinguishes them from the foreign oppressor and from the Europeanized upper strata, infidels in deed or spirit. The Muslim ‘clergy’, in large part poor, discredited by the occupier, faithful to the values of the traditional society in which they lived, belongs to the poor, constitutes their leadership and speaks to them in their own language, a language at their level. But, with independence, however, the ‘clergy’ climbed step-by-step the social ladder. The more-or-less exploiting upper layers increasingly proclaim their attachment to Islam in their frenetic search for an ideological guarantee for their social and material advantages. The more 'clerics' rise in the social strata, or even simply integrate into the nation, the less Islam will be for the disinherited an exclusive ordering principle. [6]

In such circumstances, if a conflict were to erupt in post-independence Algeria, for example, the peasant would, according to Rodinson, follow the religious over the political leader. It is here that the ‘Frenchness’ of Rodinson - something he revealed most in the last period of his life, when he would take against ‘the communitarian plague’ [7] - becomes explicit: according to him, it may be necessary, for the political education of the formerly colonised masses, to put into motion certain secular measures, as in the Christian countries, such as the separation of church and state. If there was nothing of the laïcard about him, at least in the sense we mean it today - he did not perceive Islam as a regression, [though] neither as more advanced - it is clear all that same that he wrote in a certainAufklärung (Enlightenment) tradition, for which scientific truth was above any political consideration. Thus, aboutIslam and Capitalism, George Labica wrote in 1967:

One can’t deny [...] the merit of his calling for and even provoking confrontations, like all authentically generous thought, where mutual loathing [anathèmes réciproque] and trials of motives might finally be replaced by the rigours of scientific examination. [8]

This rationalism, sometimes a little tainted with Eurocentrism, does not however in any way signify either a ‘war’ against Islam, or against ‘religion’ as such, or a call to ‘enlighten’ colonial subjects. In his preface to James Thrower’s book Marxist-Leninist ‘Scientific Atheism’ and the Study of Religion and Atheism in the U.S.S.R., Rodinson suggests that the ‘Western’ critique of religion had merely replaced religion with a new ideology, which though conserved the same functions:

This critique of religion, practised in the West since the Enlightenment - the Marxist and Soviet theses are the latest form, sometimes coarse, sometimes refined - appear as no more than interested, practical politics, as some vulgar maneuver. It is also an effort towards replacing the traditional religions with a new ideology, endowed with the same functions. [9]

Rodinson’s relationship with the enlightenment tradition, with atheism and with religion, is present in a number of his works - notably in his magisterial biography of the Prophet [10]. It was a point to which he returned in his preface of Kazem Radjavi’s 1983 book, La révolution iranienne et les moudjahédines:

I am myself a rationalist, a loyal son of the European tradition of the Aufklärung. But, I long ago renounced the idea, which flows quite naturally from this tradition, that religion is equivalent to an absolute night of the spirit, with the corollary being that to break from religion was to enter a world of true thought, demythologised, transparent, with an absolute equivalence between reality and the concept of it. Similarly, it is necessary to renounce the idea that an alienated vision of the world might not result from a class holding of proprietorship over means of production (or of men, or the earth), from the exploitation which results, and from the utilisation of religion towards better acceptance. [11]

Thus, the amicable critique Rodinson addressed to Ouzegane’s perspective was more concerned with the political consequences of the use of Islam as a tactic in the national liberation struggles than over the Muslim religion as such. In the same way, according to Rodinson, there was never anything intrinsically anti-socialist in Islam, defending the idea that the only barrier to socialism in the Muslim countries would be to put in place anti-Muslim politics.

Communism and colonialism

Rodinson’s interest in the relations between Islam, Muslims, and communism is one of the explanations for his fascination for the Tartar Bolshevik Sultan Galiev, who opposed those revolutionaries who wanted to struggle against Islam, and defended the idea of the necessity of, so to speak, ‘Marxising’ Islam. As Matthieu Renault wrote:

There is not for Sultan Galiev any incompatibility between socialist revolution and Islam: it is not necessary to work towards the destruction of Islam, but rather to it’s despiritualisation, to it’s ‘Marxisation’.[12]

In 1960, Rodinson had published a text on Sultan Galiev in Les Temps Modernes. This article was a presentation of a book, published by Alexandre Bennigsen and Chantal Quelquejay, on ‘Sultangaliévisme’,The National Movements of the Muslims of Russia, Vol I: ‘Sultangaliévisme’ in Tartarstan. The text in question is interesting for more than its title, notably for showing the fascination that Maoism exercised over Rodinson (he saw in Sultan Galiev a precursor to Maoism), and for the reference to the development of an African-Asian bloc that Rodinson compared with a Colonial International, which Sultan Galiev had called for, to ‘assure the hegemony of the underdeveloped, colonial world over the European powers’. [13] If Rodinson was interested in the figure of Sultan Galiev, it was especially for Galiev’s supporting the fact ‘that there are contradictions in the socialist regime’ [14], for example those concerning the question of national minorities within the USSR, in explicit reference to Mao’s celebrated text of August 1937,On Contradiction. Rodinson’s leaving the PCF, near the time he wrote the Galiev article, is particularly illuminated by the criticism he addressed to communist organisations [15] for the near-absence of a targeted struggle to overcome these contradictions:

Every time someone puts a light on one of these contradictions, concretely, it is either denied or minimised. Naturally, the dogmatiques search not at all to analyse, to explain, or to find the causes and the repercussions. They represent the politics followed by Communist leaders (dirigeants) in every phase, as though determined by a superior wisdom which faithfully follows all the fluctuations of the national and global conjuncture, since they are armed with the infallible ‘compass’ of Marxist teaching. [16]

He added further:

Altogether, until a very recent time, and with some understandable excuses, the communist dirigeants have been as little lucid as to the capitalist world in regards the dreams of the colonised people. [17]

Thus, to summarise the conception Rodinson had of the relations between communism and colonialism, it is evident that he wished to struggle against the white hegemony and the racial-colonial contradictions within socialism and communism, being reasons that revolutionaries ought to, according to Rodinson, study Sultan Galiev - but, he perceived that the direction in which Islam was developing in the newly independent countries was potentially dangerous politically. Rodinson had moreover never been a Third Worldist, as the movement had existed in France in the 1960s and ‘70s, writing in the prologue to Islam et capitalisme:

I do not the subscribe to the mystique of the Third World, now so widespread in Left circles, and do not beat my breast daily in despair at not having been born in the Congo or somewhere like that. Nevertheless the problems of the Third World are indeed crucial [...] [18]

In the same way that he thought that scientific truth should not be sacrificed on the altar of anti-colonial revolution, Rodinson wrote in his small book La Fascination de l’Islam (1978) that the solution to problems that the Third World would face would not be found in the nationalist ideology of the former colonisers, ideology which, though Rodinson recognised its pertinence, involved a number of limitations, from a scientific point of view. [19]

Rodinson thus attempted to navigate across a political minefield when it came to discussing the relation between Islam and anti-colonial struggles. From 1958, the year in which Rodinson quit the PCF, through the 1970s and 1980s, he more and more evolved towards an ‘independent’ perspective, without ever becoming, for that, a ‘renegade’. As Gilbert Achcar wrote in his preface to the English edition of Marxism and the Muslim World:

[...] While remaining very much involved in political discussions [...] [Rodinson] developed a critical open brand of Marxism, which he labelled ‘independent’. His relationship to Marxism evolved into an effort to salvage Marx’s method of enquiry along with key tenets of his thought, while engaging in provocative, iconoclastic debates with organised Marxists: from seeking at first to convince or influence them - the perspective that informs the essays gathered here - to an increasingly disenchanted and mordant attitude as the Communist movement went deeper into agony. [20]

The Islamic Revolution

Multiple cases of spirituality have existed. All have finished very quickly, in general, by subordinating worldly ideas, posed initially as flowing from a spiritual or ideal source, to the eternal laws of politics, which is to say the struggle for power. (Maxime Rodinson, L’Islam politique et croyance)

Another major event which inspired Rodinson to reflect on the relations between revolutionary processes and Islam was the Iranian Revolution of 1979. To properly grasp Rodinson’s interventions over Iran, it is essential to briefly return to the origins of the revolutionary uprising of 1979.

From the beginning of 1960s, the Shah’s Iran had known an economic crisis, coupled with a political crisis, without precedent. Faced with the aggravation of political crisis, the government of the Shah ordered in 1963 a series of reforms which entered into posterity under the term the ‘White Revolution’. These reforms had as objective the establishing of a stable economic, social and political base for the regime, favouring two groups: middle class peasants and the petite bourgeoisie of functionaries. The objective of the Shah, and of his Prime Minister Ali Amini, was to ‘modernise’ the country. The big losers of the reforms were, in the first place, the traditional middle class of the bazaars. Their position was constantly menaced by capitalist development of Iran. In parallel, the rural exodus was accelerated, and a large number of agricultural workers migrated towards the towns, in search of the ‘grand civilization’ their radios said was in full expansion, without finding, in fact, work there. There was a huge gulf between the promises of the regime and Iranians’ expectations. This development was visible, on the one hand, from the modernisation of Iranian economic life by the state, involving a process of cultural development and, above all, of the productivity of the working class, and on the other, the persistence of older forms of exploitation. The Shah’s modernising force was also strongly marked by a will towards ‘secularisation’ - a centralised forced march - that progressively turned religious authorities against him, especially an Ayatollah who would become leader of the Islamic Revolution: Ruhollah Khomeiny. The Shiʻah ‘clergy’ would come to marshall the majority of the opposition, taking the lead from 1975 onwards, from a left opposition affected by state repression. In effect, despite the façade of political liberalisation, political repression increased, with the economic modernisation of Iran paired with a reinforcing of the repressive apparatus. In the 1970s, the assassinations and torture were the everyday lot of the greater part of the opposition. According to Maryam Poya [21], the state’s repression led to the crystallisation of the opposition into two tendencies: a guerilla movement on the one hand, and a Shiʻah ‘clergy’ on the other. In 1975, those existent political parties were dissolute, and only SAVAK-supervised trade unions were authorised. The Shah announced the establishment of a single-party system, financed by ‘the free world’. Over the 1970s, it was thus the Shiʻah clergy that took the leadership of the opposition, and who called for a massive mobilisation against the regime of the Shah. The ‘clergy’ organised the opposition around the rejection of ‘Westernisation’ and of the submission to the imperialism incarnated in the Shah. The Islam mobilised as a means to speak with the masses was an Islam of liberation, directly addressing the political and social conditions of the majority of the population. It was without a doubt Ali Shariati who furnished the most important theoretical formulation of this liberation struggle, in defining Islam as revolutionary praxis. It was this revolutionary role conferred to Islam that provoked a number of European intellectuals to respond - including Rodinson.

In a Nouvel Observateur article on the 19th February 1979, entitled ‘Khomeyni et la “primauté du spirituel”’ (‘Khomeyni and “Spiritual Primacy”’) Rodinson elaborated not only on the significance of the Iranian revolution, but also on the reactions that it provoked amongst French intellectuals. In the introduction which accompanied the re-publication of the article in L’Islam, politique et croyance (Islam, Politics and Belief), Rodinson wrote that:

The hope, dead or moribund for a long time, for a global revolution, one which would liquidate the exploitation and oppression of man by man resurged, timidly at first, then with more assurance. Could it be that, in a most unexpected fashion, this hope is coming to be embodied now in the Muslim Orient, up until now hardly promising, and more precisely, where man is lost in a universe of medieval thought? [22]

Returning to the fervour that the revolution had provoked in a number of intellectuals, Rodinson noted, as he had in his debate with Ouzegane, that ‘the mobilising force are Islamist slogans’, adding later that ‘the Iranian liberal democrats and Marxists were asking more and more whether they had been mistaken in dismissing the traditional religious fervour of the people’ [23]. 'The Iranian revolution seemed, indeed, to justify the disquietude expressed by Rodinson on the subject of post-independence Algeria, and added to the désillusion of many of its most fervent supporters - Iranian and Europeans - faced with a new regime, and with the utilisation of Islam by the state.

The essay which Rodinson particularly addressed was Foucault’s. In their work Foucault and the Iranian Revolution, Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson somewhat caricature Rodinson’s critique of Foucault when they write:

While we find many of Rodinson’s critiques of Foucault compelling, we certainly cannot agree with his argument for the advantages of a purely socioeconomic approach to the realm of the political over a philosophical one.

In this study, we have argued that there were particular aspects of Foucault’s philosophical perspective that helped to lead him toward an abstractly uncritical stance toward Iran’s Islamist movement. If a philosophical perspective per se were the problem, how then could equally philosophical feminist thinkers like de Beauvoir and Dunayevskaya have succeeded in arrivingat a more appropriately critical stance toward the Iranian Revolution? [24]

Indeed, whilst it’s true that in Islam, Politics and Belief Rodinson wrote that ‘the spirits of philosophical formation (...) are the most exposed to seduction by theoretical slogans’ [25], Afray and Anderson never referenced Rodinson’s other texts - those which would have allowed them to nuance their criticism. One issue is that the question of philosophical grounding of Foucault, occupied no more than a limited place in the criticism they addressed to Rodinson; another is that Rodinson was far from arguing for a ‘purely socio-economic’ approach. Rodinson, who was considered as, in part, philosophe-like [26], aimed at professional philosophers - French, above all - the reproach of writing on every subject without being properly informed, and of a certain form of idealism:

The culture currently fostered in the universities - and especially the École normale supérieure - houses philosophical dissertations without much information or serious argument: they keep clear of concrete problems, and even of more general problems [27]

Rodinson’s reproach of Foucault was above all for the weak knowledge of the subject he dealt with. But, beyond Foucault, Rodinson’s essay in the Nouvel Observateur at the moment of the Iranian revolution was part of his more general reflecting on the place of Islam in revolutionary processes. Much ink was spilled on the role of Islam and religious leaders in the revolutionary processes at the end of the 1970s and early 1980s. Hence, in his classic AllThat Is Solid Melts into Air (1982), the great American theoretician of modernity Marshall Berman (1940-2013) made several references to the Iranian revolution, notably when he wrote, on Act Four, Part Two of Goethe’sFaust:

The alternatives, as they are defined in Act Four, are: on one side, a crumbling multinational empire left over from the Middle Ages, ruled by an emperor who is pleasant but venal and utterly inept; on the other side, challenging him, a gang of pseudo-revolutionaries out for nothing but power and plunder, and backed by the Church, which Goethe sees as the most voracious and cynical force of all. (The idea of the Church as a revolutionary vanguard has always struck readers as far fetched, but recent events in Iran suggest that Goethe may have been onto something.) [28]

This question - how to position oneself vis-à-vis revolutionary processes in motion? - is essential in the thought of Rodinson. In his much-cited preface to Kazem Radjavi’s book, Rodinson did not condemn the revolutionary process for its religious references - this argument had long been central to his reflections. He was interested above all in the practices of the Khomeinist government post-revolution:

It is often very difficult to appreciate the moment when the justifiable defence measures of a new regime degrade into cruel, barbaric procedures. These are able also to co-exist so easily with continued, important ameliorations for the great masses. We ought to hesitate before compromising these ameliorations through denouncing these cruelties. We are here before terrible dilemmas. But, experience has taught us that there are lines which we should not allow to be crossed without doing all we can to prevent it, a point beyond which the cruelty of means irredeemably corrupts the best of ends. I believe this point has been reached in Iran. [29]

For Iran, as for Algeria, far from making Islam an explanatory factor of the revolutionary or postrevolutionary process, Rodinson rather attempted to apply a rational analysis - ‘the only relatively certain guide we have’ [30] - to the Muslim world.

As Gilbert Achcar notes in Marxism, Orientalism, Cosmopolitanism, the end of the 1970s marked ‘a major turning point in Oriental and Islamic studies’ [31]. Achcar gave three principal reasons for this evolution: the Iranian revolution of 1979 and the establishment of the Islamist Republic; the development of the armed Islamic rebellion against the left-wing dictator of Afghanistan; and the publication of Edward Said’s classicOrientalism, in 1978. On the first two points, we have seen that Rodinson did not at all see either the religious or the ‘Oriental’ character of these processes as determinant. However, the theoretical interventions of Rodinson were not limited to an analysis of social process in the Muslim world; he also debated the most important intellectuals of the time, foremost among whom was Edward Said.

The Fascination of Islam, Orientalism, and the theory of two sciences

In 1980, the same year of the French publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism, Rodinson published a collection of texts under the nameLa fascination de l’Islam. Rodinson was considered a major intellectual by Said, though he was not his principal intellectual reference. Hence, when Said addressed the ‘canonical theses supported by the Orientalists, whose ideas on the economy never go beyond affirming the fundamental incapacity of Orientals for industry, commerce, and economic rationality’ [32], he mobilised Rodinson’s bookIslam and Capitalism as a counter-example, and affirmed the work as marking a rupture from those clichés about the ‘Orientals’. In the same manner, he called Rodinson amongst ‘theérudits (...) and the critics who have received an Orientalist education [and who] are perfectly capable of freeing themselves from the old ideological straightjacket of orthodoxy.’ [33]

In the introduction of the 1993 edition of The Fascination of Islam, Rodinson seems to have also held Said in high esteem:

I implore my readers to read Edward Said’s book, Orientalism, the French translation of which, appearing near the time of the first edition of my small book, had a great success.

The work of this Palestinian, now professor of English and comparative literature at the University of Columbia in New York, greatly cultured in English and French literature, has had a large success in the Anglo-Saxon world. He has provoked in the professional Orientalist milieu something close to a trauma. They certainly had the habit of seeing criticism of their work [as being] ‘ethnocentric’, and of being denounced by the ‘indigenous’ publications as agents, conscious or unconscious, of Euro-American imperialism. But these works didn't affect the very milieu in which they were developing. But here suddenly were all the same accusations reprised in English, by a professor of well-known value, familiar with Flaubert and Coleridge, invoking the ideas of Michel Foucault! [34]

Yet, as intellectually beneficial as this ‘trauma’ might have been, Rodinson maintained nothing less than a critical attitude vis-à-vis the central work of Said. The principle problem in Orientalism did not reside, according to Rodinson, so much in Said’s interpretation of Orientalism as such - despite certain limits he pointed to [35] - than in the use that might be made of the methodology deployed by the book’s author. Rodinson defended, indeed, the idea that ‘taken to the limit certain analyses and, still more, certain formulations of Edward Said fall into a doctrine that is, by all appearances, the Zhdanovian theory of The Two Sciences’. [36]. Rodinson wrote too that ‘pushed to the extreme’, such a theory ‘leads to more Lyssenko’. It's necessary to note that, despite the fact that Rodinson's warning is apparently self-evident, one could say, without risk of being anachronistic, that it anticipated certain contemporary debates between Marxists and proponents of post-colonial studies. Rodinson then not only warned against Said’s book itself, but against the uses it might be put to:

Whatever the importance of the deviations caused by the colonial situation to either reason or data, whatever the necessity to fight them, and however important the entrance onto the scene of the judgement of colonised and ex-colonised experts is, using their usual sensitivity against these deviations, it is indispensable to not slide carelessly towards the doctrine in question, that of the Two Sciences. [37]

Still, in the The Fascination of Islam, Rodinson devoted an entire chapter to the development of Arab and Islamic studies in Europe. He criticised the rejection of certain aspects of the social sciences, too quickly accused of Eurocentrism in his eyes. As we have seen before, despite all the sympathy that Rodinson had with the decolonisation movements, he refused this accusation, and went further: