Here’s my face/ I speak for my difference….

Jairus Banaji

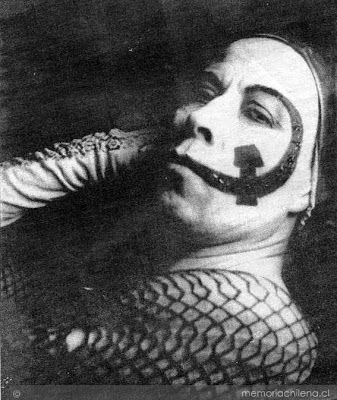

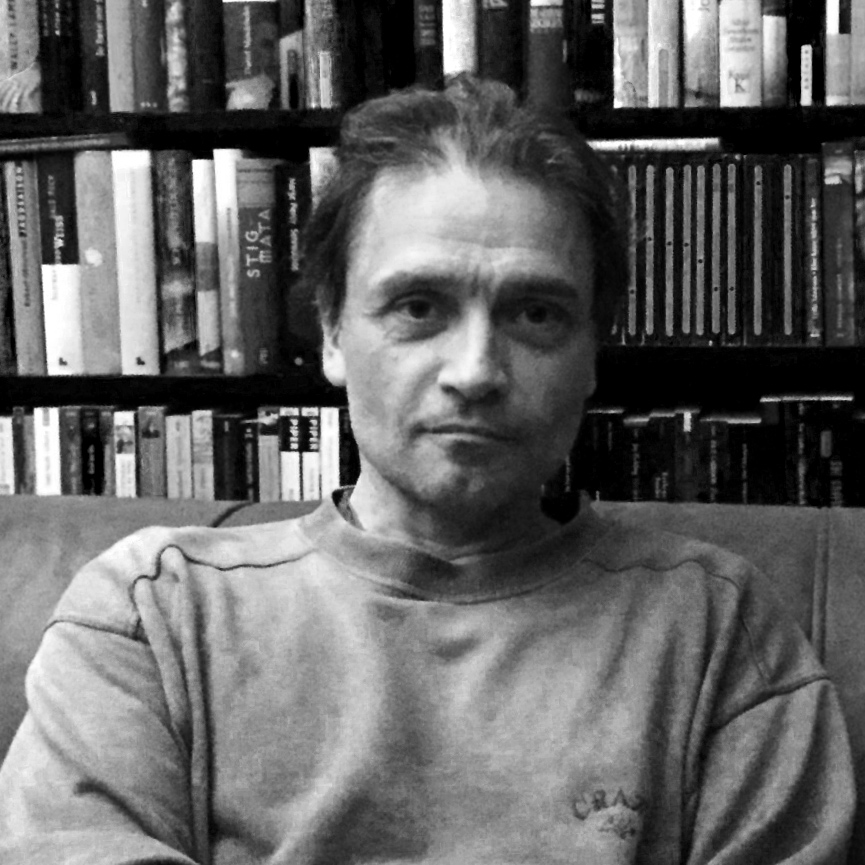

Pedro Lemebel (1952–2015), Chilean performance artist, writer and queer activist who was twice fired from his job as a high-school art teacher for openly identifying as gay. In the eighties, Lemebel created a performance troupe that would disrupt public events to dramatise issues of oppression. One of the most notorious of these public interventions occurred in 1986 when Chile was in the last years of Pinochet’s dictatorship, but it was an intervention aimed at breaking the culture of homophobia on the Left. The image shows Lemebel as he appeared during this intervention, interrupting a meeting of left-wing opposition parties.

“In high heels and make up depicting a hammer and sickle emerging from his mouth and extending to his left eyebrow, Lemebel denounced the homophobia of the Left in his ‘Manifesto: I Speak for my Difference’ to a bewildered, even hostile, audience perplexed at the cross-dressing revolutionary they had difficulty recognising as a figure of left-wing militant politics. Also marking his literary debut, the intervention staked out the space of marginality and difference that Lemebel unapologetically inhabited and rendered visible through his actions: “No soy un marica disfrazado de poeta / No necesito disfraz / Aquí está mi cara / Hablo por mi diferencia / Defiendo lo que soy / Y no soy tan raro” (I’m not a fag disguised as a poet / I don’t need a disguise / Here’s my face / I speak for my difference / I defend what I am / And I’m not that unusual).”

Born in an impoverished suburb of Santiago, Lemebel always identified with the poor and the marginal in Chile’s society, describing himself repeatedly as “maricón, pobre, indio y viejo” (a poor, old, indigenous fag). “The dictatorship targeted not only left-wing ‘subversives’”, Kate Averis writes, “but homosexuals, the indigenous, the indigent, and other identities deemed non-assimilable to a model of national identity of which the white, heterosexual, ‘masculine’ military men most closely approximated the ideal”.

In the nineties Lemebel went on to publish three Chronicles that were essentially collections of short texts depicting lives at the “social, political, sexual and ethnic margins he himself occupied”. Here, “Much like the reappropriation of ‘queer’ by queer activists and theorists, Lemebel reappropriates the homophobic language used in Chile to divest it of its derogatory tone by using it in self-designation”. It was the crime fiction writer Roberto Bolaño who eventually brought his work to audiences abroad by arranging to have it published in Spain. Lemebel died of cancer in 2015.

https://minorliteratures.com/2015/02/09/pedro-lemebel-farewell-to-a-queer-icon/

A translation of Manifesto is available here:http://cordite.org.au/poetry/notheme4/manifesto-i-speak-for-my-difference/

A Great Little Man: The Shadow of Jair Bolsonaro

By Jeffery R. Webber

Running on the ticket of the little-known Social Liberal Party (PSL) in Brazil’s general election last October, the virtually unknown Jair Bolsonaro, a former army captain and marginal congressperson representing a Rio de Janeiro riding since the early 1990s, promised to be tough on crime and corruption.[1] Cultivating an outsider persona, he won the second round with 55 percent of the popular vote, while Fernando Haddad, a progressive political scientist, former mayor of São Paulo, and Lula’s hand-picked successor as leader the Workers’ Party (PT), captured 45 percent. Haddad’s showing in the second round nonetheless exceeded expectations, given the fact that he entered the race so late in the day. The PT took a very long time to come to grips with the fact that Lula would remain in prison and could not ultimately sustain his candidacy. Partially as a result of this overdue embarkation, Haddad secured only 29 percent of the vote in the first round.[2]

In an unexpected boon to Bolsonaro’s campaign, he was stabbed in early September at a campaign rally by a mentally disturbed man. The notably inarticulate candidate for the PSL was thereafter able to avoid all scheduled debates with opponents. Instead, he tweeted directly to his followers over an extended convalescence. Meanwhile, Haddad raced around the country, speaking at endless events, in an attempt to make up for lost time.[3] Following Bolsonaro’s late surge in the polls and surprisingly robust finish in the first round, the representative bodies of domestic and international capital, as well as their mouthpieces in the mainstream media, abandoned their traditional parties and rallied behind him to thwart any chance of the PT resuming office.

Bolsonaro, as Perry Anderson notes, ‘took every state outside the north-eastern redoubt of the PT; every major city in the country; every social class with the exception of the very worst off, living on incomes of less than two minimum wages; every age group; and both sexes – only among the cohort between 18 and 24 did he fail to win a majority of women’s votes.’ And yet, while the enthusiastic right-wing core of his support base celebrated with frenzy in the streets at the results, ‘there had been no great rush to the polls. Voting is compulsory in Brazil, but close to a third of the electorate – 42 million voters – opted out, the highest proportion in twenty years. The number of spoiled ballots was 60 percent higher than in 2014. A few days earlier, an opinion poll asked voters their state of mind: 72 percent replied “despondent,” 74 percent “sad,” 81 percent “insecure”.’[4] Boundless disillusion in the PT was one important factor in the forlorn societal condition which ultimately sanctioned the rise of a grotesque to the presidency.

Part of a wider implosion of the political centre in many of the world’s ailing liberal democracies since the onset of the Great Recession in 2008, the Brazilian elections witnessed the utter routing of capital’s preferred candidate, Geraldo Alckmin, who ran for the Party of Brazilian Social Democracy (PSDB), the traditional representative of international capital and the party most associated with neoliberal restructuring. Likewise, the other long-established party of the centre-right, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), under the leadership of Henrique Meirelles, was annihilated. On the centre-left, the PT accelerated its decline, which began as early as 2014, although it retained its position as biggest party in the lower house of congress, and won four state governorships. The Brazilian Communist Party (PCB) didn’t even receive a sufficient number of votes to allow access to public resources and television air time, and the same was true of the campaign by environmentalist Marina Silva of the Sustainability Network (REDE).[5]

Brazil’s open-list proportional representation system has long been characterized by hyper-fragmentation in the two houses of congress, and a form of rule commonly known as ‘coalition-presidentialism’, whereby the centralized power of the executive must be coordinated with a decentralized and fragmented legislature. The consequent methods of rule typically involve the president gifting cabinet positions and other benefits to an array of small parties in congress in order to ensure a governable coalition.[6] The congressional results in the October 2018 contest, which ran parallel to the presidential ballot, heightened the traditional centrifugal scattering of micro-parties, and made visceral the collapse of the political centre. In the most splintered congress in Brazilian history, with over 30 parties finding representation, Bolsonaro’s PSL rose from 8 to 52 seats in the 513-seat chamber of deputies, while, as noted, the PT remained the biggest party in this domain, with 56, but was still down 13 from its previous position. As a whole, centre-right and right parties loosely aligned with Bolsonaro’s PSL dominate the lower house, and by one credible measure right-wing representatives in the lower house rose from 190 in 2010 to 301 in 2018. In another reflection of the pervasive sentiment of anti-politics in the country, voters rallied to perceived outsiders, with the traditional PSDB and PMDB’s congressional representation halved, and more than 53 percent of seats in the Chamber of Deputies seized by newcomers. Likewise, in the Senate, while 32 incumbents ran for re-election, only eight were successful.[7]

How to assess the new Brazilian regime? Early as it is in Bolsonaro’s rule, some broad stroke preliminaries are possible. In what follows I trace the political paralysis of the first five months, the popular social base of Bolsonarismo, its relationship to capital, and the role of evangelical Pentecostalism. I offer a biographical profile of Bolsonaro himself, map the three pivotal factions constituting the new government, and assess the economic outlook of the country. To anticipate the basic conclusions: the Bolsonaro regime is a weak and internally divided far-right regime, with declining popular support; capital backed Bolsonaro as a way out of crisis, but thus far the regime has not delivered, and the markets are losing faith.

Manic Stasis

Bolsonaro’s first five months in office have been characterized by misrule and pandemonium – endless Twitter wars; racist, sexist, and homophobic tirades; international diplomatic dramas; corruption scandals; cabinet instability; feuds with the legislature and judiciary; attempts to officially reimagine the 1964-1985 dictatorship as a golden period of democratic rule; and generalized policy paralysis.[8] But until mass mobilizations around education cuts in May, and a general strike in mid-June, this had decidedly not been a result of strong left-wing opposition, whether in congress or in the streets, but rather an outgrowth of internal wrangling between the constitutive factions of the tripartite coalition undergirding the regime –cultural authoritarians, militarists, and neoliberal technocrats.[9]

Each week there is further haemorrhaging of popular support for the president. According to a poll from April 7, conducted by the polling firm Datafolha, Bolsonaro registered the worst approval ratings after three months in office of any elected president in a first term since democracy was restored in 1985. Thirty percent of Brazilians considered his government to be bad or terrible, 32 percent optimal or good, and 33 percent average. [10] By contrast, for the equivalent period in office during their first terms the disapproval ratings for former presidents Fernando Collor, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and Dilma Rousseff were 19, 16, 19, and 7, respectively.[11] All the same, Collor was eventually impeached, Lula imprisoned, and Dilma thrown out of office by an institutional coup d’état.

Dangers lurk everywhere in the ensuing ataxia of the Brazilian body politic. ‘There is an atmosphere of pervasive violence in the country, which may be the way in which this administration tries to support itself, through a growth in organized and disorganized violence,’ the political economist Alfredo Saad-Filho suggested in a public conversation we held in early March at Goldsmiths, University of London. ‘But other than this, it is a circus of horrors, absolutely disorganized. Which may be a good thing for the left, in the long term. Because as they are fighting amongst themselves, they are not doing horrible things to everyone else. But I think this is a very small consolation. The political program of this government is intrinsically and heavily destructive of citizenship, of collectivity, of any form of social cohesion. There is absolutely nothing good associated with the social forces supporting Bolsonaro. It is an absolute political tragedy, and the left, still, is completely disorganized.’[12]

The Base

What do we know of the social composition of Bolsonaro’s mass base? What of his relations to capital? One pithy phrase, ‘the bull, bullet, and bible’ bloc, captures part of the picture, insofar as it highlights the centrality of agribusiness, the arms industry, and religious conservatism.[13] Agribusiness, ideologically attracted to Bolsonaro’s vision of freeing-up access to weapons and criminalizing rural workers’ movements, rallied particularly effectively to Bolsonaro in the south and central-west of the country.[14] Finance and large domestic industrial capital backed Bolsonaro only late in his campaign, after Alckmin failed to gain traction with the electorate, and other ‘outsider’ names were trialled without success. It was Bolsonaro’s move to bring on board neo-classical economist Paulo Guedes that eventually secured their backing. This was also true of Wall Street and international financial markets more generally, who were finally convinced that Guedes would ensure ‘the necessary reforms and privatization of the last state-owned companies, such as Petrobras.’[15] Ultimately overcoming their doubts in Bolsonaro, and fearing victory of the PT in the second round above all else, ‘every single business association, at every level, supported Bolsonaro. Every single business person who appeared on the media supported the right.’[16]

On a more general scale, the demographic with the most confidence in the present administration is evangelical and male, with above average educational attainment, earning more than five times the minimum wage, and living in the south of the country.[17] This is the voter profile most attracted to the ideological signifiers of lava jatismo (anti-corruption),antipetismo (antipathy toward the PT), anti-politics, ‘traditional’ moral values, and the promise of ‘law and order.’[18] The upper orders of Brazil’s urban metropoles have cultivated a particularly stark class resentment of the modest redistributive gains of the PT era – annual minimum wage increases, expansion of access to higher education, social and racial quotas, improvements in the labour code for domestic workers, the priming of cash transfer programs such as Bolsa Família, and increases in public resources for the impoverished strata of the poorest regions in the north and northeast. That these measures granted a novel quotidian presence of Afro-Brazilians and working class citizens in the heretofore exclusive spatial domains of the rich and the white – shopping malls, universities, and airplanes – was an affront to an elite way of life, a powerful psychosocial component of upper middle class support for Bolsonaro.[19]

Such ressentiment possibly runs even deeper among the lower middle classes, who enjoyed improved access to consumption, university, and formal employment in the high era of the PT (2003-2012), but who have since watched these material gains evaporate, along with their social privileges, as a consequence of economic meltdown.[20] Some have ended up as deeply precarious and indebted workers, the canonical Uber drivers and cosmetics saleswomen, among whom an anti-politics of bitterness is directed principally toward the PT, and increasingly finds combination with animus for feminists, LGBTQ+ people, and leftists.[21] Joining the downwardly mobile lower-middle-classes-turned-precarious-workers in their support for Bolsonaro are a petty bourgeois layer of commercial retailers and liberal professionals – doctors, lawyers, engineers, and the like – with a shared animosity for taxes and state provision of social rights.[22] Intermediate tiers of the social structure gravitated to Bolsonaro in large numbers, while capital cohered behind him as a last route out of crisis.

Evangelism

But there remains a missing element in this sociological audit. Indeed, one of the most critical combustible elements in Brazilian society, the political consequences of which are only understandable in relation to labour market transformations and capitalist crisis, has been the monumental rise of evangelical Pentacostalism. Though raised a Catholic, Bolsonaro inaugurated his public dalliance with evangelism on May 12, 2016. Dressed in white, he was filmed being baptized in the River Jordan – where, according to the Bible, Jesus himself was baptized – by a Brazilian evangelical pastor of the Assembly of God.[23] Even so, the current president identified himself at the time as Catholic, and has never since renounced his faith.[24] His adult sons are evangelicals, as is his third and present wife, Michelle Bolsonaro, a sign-language interpreter who plies her trade in Pentacostal circles. The president’s last wedding was officiated by the influential pastor Silas Malafia, also of the Assembly of God. Travelling in these intimate cliques, Bolsonaro has managed to sustain a popular ambiguity as to his Catholic-evangelical identity, a not inconsequential political advantage.[25]

In his first public appearance following victory last October, Bolsonaro participated in a televised evangelical sermon, conducted by pastor and ex-senator Magno Malta; it was transmitted to millions of Brazilian television screens.[26] In Bolsonaro, evangelicals have found a spokesperson, even while he continues to enjoy the support of the most conservative wing of Catholic society, signalled, for example, by the devotion to the president of archbishop of Rio de Janeiro, Orani João Tempesta.[27] Similarly, while the current president is embraced as more or less evangelical by the evangelicals, his chameleon religiosity has allowed him to circumnavigate the ordinary disdain for evangelism found in the most privileged and well-educated strata of Brazilian society.[28]

The difference separating Bolsonaro and Haddad was 10.76 million votes.[29] Roughly 56 percent of the electorate is Catholic, 30 percent evangelical, seven percent non-religious, and one percent a composite of Afro-Brazilian religions. In the event, the Catholic vote was divided across the candidates, with a slight advantage going to Boslonaro. Haddad drew more concentrated support than Bolsonaro from the numerically insignificant affiliates of Afro-Brazilian religions, as well as the non-religious.[30] Crucially, the evangelicals acted as a bloc as never before, with their leaders harvesting years of dedicated political organizing. Although evangelicals represent less than a third of the electorate, they delivered 11 million votes to Bolsonaro, more than the difference separating him from Haddad.[31]

Despite a formal separation of church and state in the constitution of 1891 – further institutionalized in the declaration of the republic in 1899 – Catholicism has been the overwhelmingly dominant religion of Brazil, as well as being intricately bound up in the common sense notions of the Brazilian nation. Over the last few decades, however, this hegemony has suffered a relative decline, with a religious shift to evangelical Pentacostalism.[32] One authoritative account points to three dominant waves of Pentacostalism in the country. The first stretched from 1910 to 1950, during which time the Assembly of God, the Christian Congregation, and the International Church of the Four Square Gospel were established. These now constitute Brazil’s classic Pentacostal churches, and are distinguished by their emphasis on the gifts of the Holy Spirit and the ritual of speaking in tongues.[33] A second wave, beginning in 1950 and closing in 1970, inducted a period of popular evangelism, with the first inroads into the communicative networks of radio and television. American televangelism was the model of this phase, with the Brazil for Christ Church and God is Love Church its quintessential institutional expressions.[34]

The last wave began when the second ended, and extends into the present. It is sometimes known as ‘neo-Pentacostalism.’ An early entrant was the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, established in 1977 by Edir Macedo, joined shortly thereafter by the International Grace of God Church, Reborn in Christ Church, Worldwide Church of God’s Power, and the evangelical community of Sara Nossa Terra. Driven by a new managerial ethos which structures religious institutions on the model of corporations, neo-Pentacostalism is doctrinally associated with the theologies of spiritual warfare and prosperity – intimately related to one another.[35]

Originating in American evangelical milieus during the late-period of Jimmy Carter and the new ascendancy of Ronald Reagan, these two theologies found a syncretic synthesis in their new Brazilian home. The ‘theology of prosperity’ advances the view that God created his children to be prosperous and to obtain happiness in this earthly world. In other words, God wants to distribute wealth and good health to those who fear him in the here and now. To guarantee earthly prosperity one needs to demonstrate one’s faith, which entails financial offerings to the church. For adherents of the theology of prosperity there is a correspondence between the strength of faith and the size of these offerings.[36] Unsurprisingly, the most successful evangelical organizations in Brazil are quasi-financial, multi-million dollar enterprises as a result. Prosperity, in the sense of this religious creed, celebrates the pursuit of personal enrichment, and implicitly casts aspersions on the poor, whose poverty is traceable to personal failings. A stratagem of individual survival in the face of a protracted precariousness at the heart of the socio-economic order nicely complements a wider deterioration of collective subjectivity in Brazilian society, and the decades-long construction of neoliberal subjects, something that was never surpassed during PT interregnum.

The theology of spiritual warfare, meanwhile, involves a belief that the world is a staging ground for unadorned confrontation between forces of good and evil. According to its postulates, the forces of evil seize hold of the faithful and are the root cause of their problems and tragedies. Exorcism, therefore, to be carried out by religious leaders, is a necessary measure to expel the demons from the faithful and thus ensure their prosperity and health. Freedom from demons becomes a natural prerequisite for wealth and earthly happiness.[37]

Table I – National Census: Percentage of Catholics and Evangelicals, 1980-2010[38]

| Census 1980 | Census 1991 | Census 2000 | Census 2010 |

Catholics | 89.2 | 83.3 | 73.7 | 64.6 |

Evangelicals | 6.6 | 9 | 15.4 | 22.2 |

A national census is held every decade in Brazil, with the next one due in 2020.[39] Table I indicates patterns of religious self-identification, with a sharp decline of Catholics from 89.2 to 64.6 percent of the population from 1980 to 2010, and an attendant increase in evangelicals from 6.6 to 22.2 percent over the same period. If we parse the category of ‘evangelical’ further, it is possible to identify over half as neo-Pentacostals (13.3 percent of the total population), with the historical Pentacostals (Lutherans, Presbyterians, Baptists, and so on) representing only 4 percent of the total, and seemingly in stagnation in demographic terms, and the remaining 4.8 percent a series of indeterminate evangelical sects (more independent, with less denominational fidelity).[40] The Assembly of God remains the biggest single institutional expression of evangelism in the country, with 12.3 million followers.[41]

While lacking the empirical depth and range of national censuses, individual studies by specialists in the area hypothesize that the rate of Catholic decline and evangelical uptick is increasing. Between 1990 and 2010, the Catholic population was losing adherents at the rate of 1 percent per year, while evangelicals were moving in the other direction at a rate of 0.7 percent. The latest specialist analyses suggest that the annual rate of diminution in Catholicism has accelerated to 1.2 percent since 2010, and the annual rate of gains for evangelism has moved in the opposite direction at 0.8 percent. If these numbers are roughly correct, Catholics will represent fewer than half of the population by 2022.[42]

As noted, there was a strong correlation between evangelical adherence and votes for Bolsonaro. In the states with the strongest evangelical presence – Rondônia, Roraima, Acre, and Rio de Janeiro – Bolsonaro was handed spectacular victories, and in the states of the northeast, where evangelicals have their weakest base, Haddad won handily. This is not to argue, of course, that religion was the only determining factor in far-right growth, but it is to point out its contingent decisiveness in the October electoral contest.[43]

Haddad made for a perfect scapegoat for organized evangelical reaction once he was finally declared the PT presidential candidate. When Haddad was minister of education during Rousseff’s first term in office, he attempted to introduce educational materials to combat homophobia in the public school system. Pastor Silas Malafia, in an exemplary response from the evangelical right, denounced the materials as a ‘gay kit,’ designed to convert children into homosexuals.[44] It was then-congressperson Jair Bolsonaro who took it upon himself to hold up the ‘gay kit’ as the empyrean of the PT’s moral depravity. Come the 2018 electoral season, Bolsonaro unleashed a tribe of social media combatants, generating a tidal wave of fake news memes, including images of babies being fed in public day care centres of the PT era with bottles shaped as penises.[45]

While Bolsonaro seemed, to many, to have simply materialized out of the ether when he assumed the presidency, in a certain sense the 2016 municipal elections in Rio were a premonition of things to come. While evangelicals had long had a presence in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s second largest city, the state capital, and home of Carnival, had long been seen as hostile territory for traditional mores and conservative religious etiquette. And yet, Marcelo Crivella, a bishop of the Universal Church and nephew of Edir Macedo, attracted voters behind a platform of antipetismo, a war on ‘gender ideology,’ and a conservatizing agenda for the public school system – depicted as a hotbed of cultural Marxism and social decadence. He successfully seized the mayoralty of Rio.[46] All of this a frightening intimation of just how quickly the extreme right can germinate when the soil shifts.

Ruy Braga, one of Brazil’s most innovative and perceptive sociologists of labour, has written the most penetrating early mapping of the complex relations between evangelism and alterations in the political subjectivity of specific subaltern layers, correspondent with the informalization of the world of work, contradictions within the PT’s development model, and the dynamics of economic crisis over the last several years.[47] The critical puzzle Braga poses is why ‘a substantial part of the working class chose a candidate clearly opposed to a redistribution agenda and who promised an attack on social security and labour rights?’[48] Conservative envagelism is definitely part of the story, but it needs to be linked, in Braga’s view, to the changing sociological conditions of a specific layer of the population – a working class layer accounting for more than a third of the electorate – which receives between two and five minimum wages; that is, impoverished workers, but not the poorest of the poor. This bracket of society used to vote consistently PT, but in 2018, 61 percent voted Bolsonaro, and only 39 percent for Haddad. The poorest, by contrast, persisted in their alignment with the PT. ‘We can infer, then,’ Braga suggests, ‘that the changing loyalties of those who receive between two and five minimum wages… is what explains the election of the PSL candidate.’[49]

There is some merit André Singer and Gustavo Venturi’s argument that low-income supporters of Bolsonaro were motivated by a concern for public safety, and were persuaded by his promise of a tough line on crime.[50] For Braga, this perspective is compelling insofar as it identifies ‘social violence as a trigger for Bolsonarism among people whose family incomes range from two to five minimum wages,’ but to stop here would be to remain on the surface of appearances, and to miss a much more thoroughgoing set of underlying structural variables.[51] If public safety was a proximate trigger, in other words, ‘the profound cause was the global tendency of frustration, particularly among precarious and informal workers living in large urban centers, with the limits (political, economic, and ethical) of the mode of development championed by former PT president Lula da Silva.’[52]

The PT development project at its peak (2003-2012) was a distributionist model rooted in an unstable class compromise, as capital continued to profit handsomely and social movement leaders were increasingly pacified through incorporation into the state.[53] Lula introduced distributive elements to the mode of rule, while maintaining a broad allegiance to the various sections of capital—agribusiness, finance, industrial, and the frequent symbiosis of the latter two. Honing a regime of multiclass conciliation, he conceded to the demands of capital while offering targeted welfare to pauperized strata dependent on the state for survival, most famously through the World Bank-lauded Bolsa Família—a conditional cash transfer program that reached millions.[54] Higher education was expanded and university quotas were introduced for Black students.[55] Millions of jobs were created, although these were mainly low-paid, unskilled, and precarious. The state invested in state-owned enterprises, particularly through the expansion of Petrobras activities in 2009, following the company’s discovery of deep-sea reserves in the Atlantic.[56] Expansionary policies were introduced in 2009–2010 in the wake of the global crisis, drawing on foreign reserves that had been accumulated at high rates during the commodities boom.

During the boom years, the PT was capable of lubricating its multiclass alliance, targeting modest social reforms at the poorest, providing employment, and raising the minimum wage and living standards, all the while allowing the rich to capture a disproportionate share of the wealth being accumulated. At the same time, under the second Lula administration there was no diversification of exports, the technological content of manufacturing production remained the same, and infrastructural investment, including basic urban services of transport and water—flashpoints in coming protests—was severely neglected.[57] Critical to the transformation in political subjectivity among those earning between two and five minimum wages was the combination of poor jobs, urban infrastructural decrepitude, and accelerating personal indebtedness. Between 2005 and 2015, ‘total debt owned by the private sector increased from 43 to 93 percent of GDP,’ Anderson points out, ‘with consumer loans running at double the level of neighbouring countries. By the time Dilma was re-elected in late 2014, interest payments on household credit were absorbing more than a fifth of average disposable income. Along with the exhaustion of the commodity boom, the consumer spree was no longer sustainable. The two motors of growth had stalled.’[58]

Braga’s ethnographic work among call centre workers in São Paulo reveals how the growing expectations of social mobility, fuelled in part by the PT’s ideological commitment to expanding a ‘new middle class,’ proved unsustainable. Consumption increased significantly, but it did so through the snowballing indebtedness of working class layers of the population. As workers became indebted they were more likely to see the short-lived improvements in livelihoods as a product of their own efforts, rather than as a consequence of PT social programs or economic policies.[59] When the economic crisis began to pinch in 2013, these livelihood gains for many informalized workers disappeared and they became embittered by targeted social programs like Bolsa Família and university racial quotas, from which they never directly benefited. Priced out of urban residential centres, they moved further and further into the distant suburbs, and their everyday experiences were mired in multi-hour commutes, a direct outgrowth of the neglect of public transport infrastructure under the PT.

Informal workers of this strata became ever more susceptible to right-wing formulations which identified such programs as responsible for reproducing the ostensible laziness of welfare recipients, on the one hand, and the corruption of the political clientelism of the PT’s rule, on the other. ‘The Brazilian far-right managed to instrumentalize this feeling through the rhetoric of “meritocracy”, appealing to popular resentment against the PT as the crisis deepened and decimated outskirts of cities, becoming increasingly dependent on notoriously inefficient public services.’[60] While social progress for subaltern layers was real under the PT, it was also always double-sided. Consumption was accompanied by indebtedness, housing ownership by longer commutes, and employment by precariousness.[61]

All the same, popular strata maintained their loyalty to the PT until Dilma’s second term, when Brazilian society’s shift to the right rapidly intensified in a distorted response to the hard neoliberal turn on the part of the government and the stark worsening of the recession in 2015 and 2016.[62] The decline of labour union density and militancy under the PT, and the rise of outsourcing, cooperative work and self-employment, helped to usher in a replacement of collective identities rooted in working class responses to shared interests with individualist identities and survival strategies. What sociologist Alan Sears has called the ‘infrastructure of dissent’ suffered protracted diminution, and in its place a neo-Pentacostal infrastructure flourished.[63] Health and other social assistance programs in the suburbs of São Paulo came to be administered by evangelical churches, even while being financed by the federal government. It was evangelism that came to be seen as serving the downwardly mobile informal working class layers, while the PT became associated with neglect and corruption.[64]

The ‘neo-Pentacostal movement today flourishes in a context of dismantling of labour protections, strengthening in low-income groups a subjectivity clearly aligned with the model of neoliberal self-management,’ Braga argues. ‘The mediation between the worker and the world of work ceases to be predominantly collective and begins to take refuge in the formulas of popular entrepreneurship.’[65] As we have seen, the ‘theology of prosperity’ neatly aligns with such individual survival strategies. With the exacerbation of informality, unemployment, and underemployment, it is unsurprising that small shop owners and more established street vendors now vie competitively with a burgeoning layer of newcomer street vendors in Brazil’s major urban centres. They grow to fundamentally resent each other, while uniting in their hatred of lumpen – the thieves and drug addicts. Meanwhile, all of the lower orders become more exposed to violent crime in a decaying social order.[66] In Brazil’s new world of work, ‘politicized collective relationships like those of the trade union movement are weakened in favour of competitive relations linked to the occupation of sales areas, as well as by the growing fear of urban violence…. If trade unionists have become distant from the everyday lives of subaltern classes, becoming less important to informal workers, it is relatively easy for a far-right candidate to associate them, for example, to the corrupt schemes of a political system in crisis, including them in the group of “good-for-nothings” who are “destroying the country”.’[67] For comparable processes to those at work in Brazil today, one need only look to the best ethnographies of working class decomposition and the rise of far-rights in Colombia and Guatemala in recent decades.[68]

In the 2018 elections, the vast, well-financed, and expanding reactionary fabric of evangelical Pentacostalism – temples, websites, television and radio stations – mobilized the novel political subjectivities of those earning two to five minimum wages, and helped transform them into Bolsonaro’s foot soldiers.[69]

Portrait of a Thug

Who is Jair Bolsonaro? With good reason, he is often set side by side with contemporaries like Viktor Orbán of Hungary, Jarosław Kaczyńsk of Poland, Narendra Modi of India, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey, Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, or Donald Trump of the United States. He is also occasionally discussed alongside an earlier generation of authoritarian Latin American leaders, such as Augusto Pinochet of Chile, or Jorge Rafael Videla of Argentina, alerting us to the potential menace of a return to a darker era – inconceivable until recently to many liberal social scientific analysts of Latin America, comforted in their echo chambers of assurance that the region’s democracies had been resolutely ‘consolidated.’

In some ways, though, the most analogous figure to Bolsonaro is the Guatemalan génocidaire Efraín Ríos Montt of the early 1980s, whose evangelical Pentacostalism ‘sustained a vision of a new Guatemala, formed from a potent mix of religion, racism, security, nationalism, and capitalism.’[70] ‘Brazil, in truth, elected a politician much more extreme than the other new authoritarian leaders,’ according to left-liberal Brazilian critic Celso Rocha de Barros. ‘Bolsonaro is the most radical subject to occupy the presidency of any democratic country in the contemporary world.’[71] Whether Bolsonaro is more extreme than Duterte, or Modi for that matter, is open to debate, but they are at least ultraists of a similar genre.

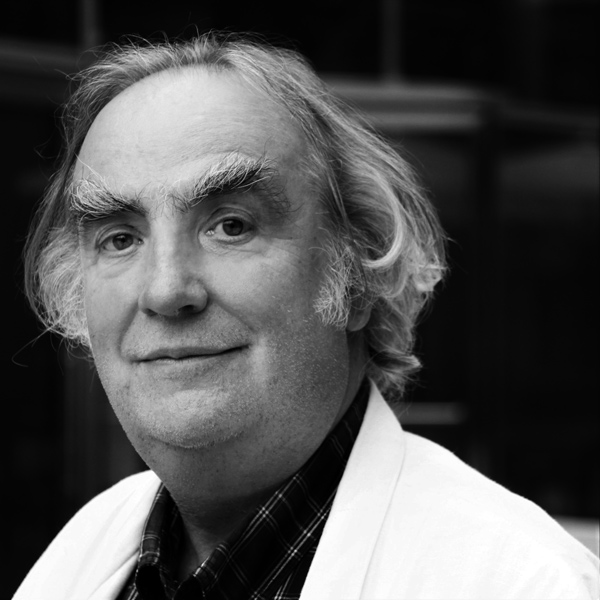

In a remarkable essay on the political culture of classical fascism, the historian Jairus Banaji explains that ‘fascist ideology is actually only a pastiche of motifs, it is a pastiche of different ideological currents, it has very little coherence on its own.’[72] In a comparable eclecticism, even if there has not been a fascist dictatorship installed in brazil, Bolsonaro’s weltanschauung revolves mainly around conspiracy, the political left, women, black and indigenous people, LGBTQ+, and environmentalists. He has famously explained that he would be incapable of loving a homosexual son, that he would rather such a son die in an accident than survive while gay.[73]

For Banaji, drawing on the work of Wilhelm Reich, patriarchal relations and the authoritarian family are the root of the state’s power in capitalist society. The authoritarian family, in this sense, ‘is a veritable “factory” of reactionary ideology,’ finding its fullest expression under fascism, ‘where this relationship between the two becomes overtly posited.’ There is a fundamental ‘resonance between the authoritarian character-structures that are moulded inside the patriarchal family and the Fuhrer ideology which is characteristic of all right-wing mass movements.’ [74] Bolsonaro’s unfettered attacks on ‘gender ideology’ recall Reich’s insight, having granted wholesale permission to unleash the worst strains of gendered violence already extant in the interstices of Brazilian society. ‘Rape is as common as murder in Brazil,’ Anderson reports, ‘more than sixty thousand a year, around 175 a day – the number reported has doubled in the last five years.’[75] Queer Brazilians have likewise been subject to unmitigated savagery. Already facing the highest level of lethal violence against queer people in the world, with 455 reported murders in 2017, the presidential election race of 2018 witnessed roughly 50 attacks ‘directly linked to Bolsonaro’s supporters; among them were at least two incidents in which trans women were killed by men who invoked his name.‘[76]

During his seven forgettable terms in the Chamber of Deputies, Bolsonaro’s main interventions turned on restoring the good memory of the military dictatorship. If anything, on this view, the dictatorship had not gone far enough in its notorious rounds of execution and torture of dissidents and activists. During the impeachment of Rousseff, Bolsonaro employed his speaking time to explain he was pledging his vote in the name of Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, head of the Doi-Codi unit responsible for the personal torture of the former PT president when she was captured during her period of guerrilla militancy against the dictatorship.

Bolsonaro has denounced fellow deputy Maria do Rosário, also of the PT, as ‘not worth raping.’ He has called immigrants ‘scum.’ The United Nations is for him a ‘bunch of Communists.’ A vociferous supporter of the military police and death squads, or militias, that specialize in the racist terrorization of the favelas in his beloved Rio, Bolsonaro has said that a ‘policeman who doesn’t kill, isn’t a policeman.’[77] His inaugural address as president pledged to ‘rescue the family, respect religions and our Judeo-Christian tradition, combat gender ideology, conserving our values.’ Bolsonaro has referred to quilombolas, descendants of runaway slaves who have a distinct legal and cultural status in Brazil, as obese and lazy: ‘They don’t do anything. They don’t serve even to procreate anymore’.”[78]

It is worthwhile to recall here Alberto Toscano’s penetrating observations on ‘capitalist folklore,’ and specifically the notion that ‘fascistic, authoritarian and right populist solutions do not require a unified conception of the world and of life; or rather that, in Fredric Jameson’s terms, they can operate with the most degraded varieties of “cognitive mapping,” with the image of “totality as conspiracy.” If the illusion of the (left) intellectual is that [quoting Stuart Hall] “ideology must be coherent, every bit of it fitting together, like a philosophical investigation,” this is an illusion that the right (especially once it leaves behind the rigor and asceticism of high bourgeois culture) need not entertain, happily flaunting its programmatic incoherence and rejection of the rationalist demand that politics have a logic, crafting its discourse to appeal in incommensurate ways to contradictory audiences.’[79]

Olavo de Carvalho is the quintessence of degraded cognition of this kind. He is to Bolsonaro what Steve Bannon was to Trump before their falling out. A Brazilian, but resident of Richmond, Virginia since 2005, Carvalho is a bizarre ‘autodidact, philosopher and former astrologer,’ with a social media audience of more than 570,000 and sufficient influence within the president’s most intimate coterie to determine cabinet selection and structure the ideological content of much of the president’s bountiful Twitter output.[80] Carvalho ‘has claimed that Pepsi is sweetened with the cells of aborted foetuses; that legalizing same-sex marriage leads to legalizing pedophilia; and that calamitous natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina and the 2011 earthquake in Haiti may be divine punishment for practicing African religions traditions.’[81] For Carvalho, ‘Brazil’s problem with violent crime might have been averted if the military regime had killed the right twenty thousand people.’[82] A recurring theme in the YouTube repertoire of the 72-year-old, pipe-smoking bear-hunter, ‘is a neo-Marxist insistence on the cultural hegemony that he claims has been imposed by globalists, the left, and the politically correct via schools, political parties, and the mainstream media and “fake news”.’[83] ‘Cultural Marxism’ has befouled the West, not least in the way it has concocted the elaborate ruse of climate change.

Channelling Carvalho’s worldview into the institution of the Brazilian presidency, Bolsonaro, ‘has been able to capitalize on the anti-political sentiments and deep conservatism prevalent among sections of Brazilian society,’ according to historian Benjamin Fogel. ‘His politics are premised on capital punishment for criminals, racism, sexism, homophobia, nostalgia for military dictatorship, gun ownership, pro-life views, and virulent anti-leftism, all combined with a dose of neoliberalism. Bolsonaro has been able to ride the anti-leftism wave unleashed by anti-corruption protests to pose as a political outsider capable of renewing the broken political system and a morally degenerate society.’[84]

As of June 2019, Bolsonaro had 9.5 million followers on Facebook, which was twice that of the country’s most important newspaper. By some estimates, he has 3.4 million Twitter subscribers.[85] Lacking a party structure from which to mobilize his core supporters and maintain their fervour, Bolsonaro depends on the extemporaneity of unmediated social media relations. As Toscano has stressed elsewhere, summoning Theodor Adorno, there is always ‘the problem of the libidinal bond that fascism requires, both vertically towards the leader (especially in the guise of a kind of play of narcissisms, the follower finding himself reflected in the leader’s own self-absorption) and horizontally, towards the racialized kin or comrade, identifying this as a technical, or psycho-technical, problem for fascism itself…. This libidinal energy is of necessitypersonalized as an ‘erotic tie’ (in Freud’s terms), and operates through the psychoanalytic mechanism ofidentification (again, both horizontally and vertically).’[86]

Prolonged degeneration of political representation in Brazil, a pronounced disintegration of political institutionality, has helped to fertilize Bolsonaro’s efflorescence. Outside of party structures, and drawing on the novel identifications allowed by social media interaction, Bolsonaro has harvested the libidinal bonds forged with his core supporters – roughly 30 percent of the Brazilian population. But only by constantly reproducing instantaneous and direct identification, stoking Twitter controversy, resurrecting the country’s institutional decay, and tilling the soils of moral panic, can Bolsonaro continue to titillate his hard core followers.[87] The sensation of participating in a Bolsonarista WhatsApp group is one of popular power, however illusory in reality, of the capacity to support, sculpt, and scold the politics of one’s leader, while rallying to his defence against enemies, internal and external. The sensation of immediacy, of ‘participatory ecstasy,’ is something many Bolsonaro supporters never experienced via the traditional political system.[88]

There may be an underlying rationale to the form of rule assumed by this inarticulate, undexterous clown, this interloper president, maligned by the mainstream media: ‘the factor that more often than not the fascist leader appears as a “ham actor” and “asocial psychopath” is a clue,’ Toscano reminds us, ‘to the fact that rather than sovereign sublimity, he has to convey some of the sense of inferiority of the follower, he has to be a “great little man”.’[89] Bolsonaro performs simultaneously as charismatic leader and man of ‘the people,’ someone sharing ‘their language, tastes, and culture.’[90] ‘Bolsonaro, the nobody – a citizen of failure – won the elections, embodying the worst features of Brazilian politics, and of Brazilian society, within himself’ – coursing through his blood, the ideological cocktail of anti-corruption, anti-crime, the hard state, and evangelical moralism. [91]

State Factions

Cultural Authoritarians

It is time now to interrogate the complex entanglements of cultural authoritarians, militarists, and neoliberal technocrats at the heart of the government in question. There are tensions and contradictions working between them, although there are also instances of overlap in specific personnel who bridge the divides, as well as moments of coincidence across currents in ideological and political purpose. Without forgetting the malleability of these lines of separation, then, let’s review each faction in turn.

Bolsonaro himself is the peak representative of the first group. The adhesive glues of this tendency involve a support base in evangelical Pentecostalism and right-wing Catholicism, an admiration for Donald Trump, antipathy toward China, aggressive hostility to Venezuela, a Zionist commitment to Israel, and such esoteric notions as Nazism being a leftist movement.[92] Joining the president in the innermost ring are three sons from his first marriage – Flávio, 38, a former lawyer, member of the legislative assembly of the state of Rio de Janeiro for the Progressive Party (PP) from 2003 to 2016, and the PSL from 2016 to 2018, and since 2019 a senator for PSL at the federal level; Carlos, 36, a city councillor in Rio de Janeiro, for the Social Christian Party (PSC) since 2001; and Eduardo, 34, a former police officer and lawyer, and member of the chamber of deputies from São Paulo from 2014-2018 with the PSC, and from 2019 onwards with the PSL.[93]

Eduardo, the youngest of the brothers, is perhaps the most extreme sibling. He is the Latin American representative of Steve Bannon’s far-right international organization, the Movement. Eduardo, long an admirer of Bannon, took it upon himself to introduce Bannon to Carvalho during a visit to the United States. The two men hit it off. For Bannon, Carvalho incarnates a new source of vitality for what he sees as increasingly sterile traditional frames of reference within American conservatism.[94] In a 2018 video, Eduardo can be seen and heard contending that the recent spate of US school shootings are the consequence of schools being ‘gun-free’ zones. Legislators protecting that reality are ultimately culpable for the massacres.[95] He won a record 1.8 million votes in last year’s congressional elections, securing his membership in the chamber of deputies.[96]

Carlos, the middle son, is known as the ‘pit bull,’ both for outspoken loyalty to his father, as well as the role he played as coordinator of Bolsonaro senior’s social media campaign during the electoral race. Carlos has since emerged as the unofficial spokesperson of the presidency in the first months of the new regime, and the most vehement antagonist of Hamilton Mourão, vice president and chief representative of the militarist faction.[97]

If Carlos has attracted controversy in the press for his role as pit bull, Flávio has also drawn unwanted attention. He is under investigation for corruption concerning alleged payments to a former adviser and other suspect financial transactions, becoming a vulnerable flank for the Bolsonaro administration, given that a key part of its raison d’être has been a concerted war on corruption, which it treats as essentially a phenomenon exclusive to the PT.[98] Flávio also employed the mother and wife of an ex police officer in Rio who is the alleged leader of a violent urban militia.[99] Flávio, like his father and brothers, is a fierce advocate of gun ownership as an individualized means of responding to violent crime. In 2017, he shot a pistol through his own car windshield in the middle of a Rio traffic jam in an attempt to gun down a suspected thief.[100]

With this family dynasty at its core, the faction of extreme ideologues also encompasses the ministries of education and foreign affairs.[101] Bolsonaro’s first education minister was Ricardo Vélez Rodríguez, an obscure, ultraconservative academic, whose main credential for the position was seemingly his tightknit association with Carvalho. Under his leadership, the ministry became a battlefield between cultural authoritarians and militarists. Vélez Rodríguez’s main efforts in the post were symbolic attempts to rewrite the portrayal of the military dictatorship in the public education curriculum and to introduce the national anthem into schools – the singing of which was to be followed by the children chanting the Bolsonaro rally cry, ‘Brazil Above Everything, God Above All!’[102]

Overstepping his authority one too many times, Vélez Rodríguez was forced from his position in early April, to be replaced by an ostensibly moderate technocrat, economist Abraham Weintraub. It is true that Weintraub has been more amenable to repairing bonds with the militarist faction, and yet his commitment to bringing the war on ‘cultural Marxism’ into the public education system rivals that of Carvalho. Like Vélez Rodríguez, Weintraub was unaccomplished as a scholar. A fierce adherent of austerity in the education sector, he is the author of the proposed reforms that catalyzed the mass mobilizations of May 15 and 30 this year.[103] Prior to taking up a position at the Univerisdade Federal de São Paulo, Weintraub had been director and chief economist at Votorantim Bank. Weintraub is a close friend of cultural extremist Eduardo Bolsonaro, but he is also a neoliberal dogmatist, suggesting elective affinities with the technocratic faction. His appointment is understood by many pundits to represent an attempt to repair some of the ill will between the main regime factions.[104]

In the realm of foreign affairs, Filipe Martins, a 31-year old advisor to the president, adherent of Carvalho, and former international affairs secretary of the PSL, has played an important role in setting the tone of this administration.[105] He is closely aligned with Ernesto Araújo, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and, with the customary ardour of youth, one of the more unrelenting reactionaries in the present government.

Araújo himself apparently owes his ministerial position to a direct endorsement from Carvalho. The West Virginia resident became aware of Araújo when the latter published a bewitched treatment of the US president and the new wave of far-right governments internationally in an article called ‘Trump and the West,’ appearing in a 2018 issue of the Cadernos de Política Exterior, the quarterly journal of the Brazilian Institute for Investigation of International Affairs, IPRI.[106] Araújo recognizes his debt to Carvalho and remains one of the guru’s most loyal disciples within government. This explains in part Araújo’s tense relations with career diplomats and civil servants in the ministry under his command, as well as conflicts with the militarist faction.[107]

Under Araújo’s command of the foreign affairs portfolio, Brazil has played a leading role in the dismantling of the South American Community of Nations (Unasur), which had sought some degree of regional autonomy for South America from US hegemony in recent years, and its replacement by the Forum for the Progress of South America (Prosur), which thus far coheres around the right-wing governments of Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Paraguay, Peru, and Ecuador.[108] Araújo is a hawk with regard to neighbouring Venezuela, and so it is no surprise that Brazil was one of the first countries to recognize the self-anointment as interim president of Brazil’s northern neighbour by conservative oppositionist Juan Guaidó.[109] The foreign affairs minister coordinated a meeting between Bolsonaro and the Venezuelan opposition in Brasília on January 17, just days before Guaidó’s declaration. According to Araújo at the time, the Venezuelan government of Nicolás Maduro has only been capable of reproducing itself through ‘generalized corruption, narco-trafficking, people trafficking, money laundering, and terrorism.’[110]

Araújo is an open admirer of the far-right nationalist governments of Italy, Hungary, and Poland. He was personally behind the extradition of Cesare Battisti, a long-time political exile and novelist in Brazil who was wanted by the Italian state for his involvement in the 1970s far-left group, Armed Proletarians for Communism (PAC).[111] Araújo’s brand of nationalism involves the notion that Brazil can play a bigger and bolder role on the world stage, but only if it subordinates itself in a tight alliance with the United States, under Trump’s leadership. He has said of the career civil servants in Itamaraty, the name of the palace which houses the ministry of foreign affairs, ‘They don’t think Brazil can be anything in the world and that we have to be content selling a few products and staying quiet, copying the agendas that come from abroad, such as the climate or human rights…. I believe that Brazil has to try to be big. This means precisely abandoning the anti-American worldview that has dominated Itamaraty.’[112]

Aligning with Israel in the Middle East is one way to strengthen allegiances with the United States. ‘When Americans see that we have positions close to theirs in discussions on the Middle East,’ Araújo stresses, ‘it makes it easier to reach out to them to discuss issues of wheat or ethanol.’ Because of Brazil’s renewed ties to the United States, if a country is inclined to take an attitude hostile to Brazil’s interests, ‘it is going to think twice, because it will see that Brazil has this alliance.’[113] Araújo was warmly received by Trump in a recent trip to Washington, and returned to Brazil with a series of announcements concerning gains made on the trip – Washington signalled support for Brazil’s aim to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and affirmed its commitment to elevate the South American country to the status of a preferential ally of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). According to Araújo, these moves indicate Brazil’s enhanced ‘international profile and return to being an important actors across all spheres,’ situating Brazil decisively ‘within the geopolitical and economic space of the West.’[114]

China, meanwhile, represents a long-term existential threat in the worldview of the minister of foreign affairs, both in terms of commercial expansion throughout much of the world, as well as in terms of its geostrategic positioning vis-à-vis the United States. For Araújo, it is clear that China will become an ever bigger problem for the ‘West’ over time. As the line being drawn between the United States and China becomes sharper, bold alignment with the former must be the option pursued by Brazil. Still, Araújo has been unable simply to ignore the dependent ties of Brazilian exporters to the Chinese market. When he is pushed by journalists to clarify if his most hawkish statements vis-à-vis China mean that Brazil will reduce its commercial linkages with the Asian power, Araújo always returns to pragmatism, acknowledging that China will continue to be a major trading partner of Brazil.[115]

A final figure of note in the Bolsonaro regime’s cultural authoritarian contingent, is Damares Alves, a ferociously conservative evangelical pastor who was given the reigns of the ministry of family, women, and human rights.[116] In addition to playing a leading part in the government’s ceaseless propaganda war on ‘gender ideology,’ Alves’s ministerial remit has been extended to include Brazil’s Indigenous Affairs Agency (FUNAI). In this domain, Alves draws on her experience evangelizing in indigenous areas of the country to execute Bolsonaro’s horrifying vision of the Amazon, environment, and indigenous territories. A key facet of the president’s perspective in this area is the ostensible alignment of indigenous interests with those of corporate mining and agricultural giants.[117]

Militarists

In contrast to the pomp and spectacle of the cultural authoritarians, the militarists, whose most visible representative is vice president Hamilton Mourão, project a comparatively quiet resolve. If the Brazilian populace has generally turned against most state institutions, polling suggests popular confidence in the armed forces remains high, indeed the highest of any state institutions.[118] Augusto Heleno Ribeiro, a former general who overseas security policy in the cabinet, says the military’s reputation for moderation is well-deserved: ‘Our style is to be conciliatory, not incendiary… That’s because we know full well the perils of extremism.’[119] Should Bolsonaro’s ineptitude in serving the interests of capital persist too much longer, the direct usurpation of power by Mourão is one plausible exit. ‘The bickering and resultant policy paralysis’ of Bolsonaro’s first months in office ‘has raised questions about Mr. Bolsonaro’s political skills and future,’ the Financial Times reports. ‘In a country with a history of vice-presidents rising to the highest office, analysts wonder if General Mourão is not already a president-in-waiting.’[120]

Lacking an institutional machinery comparable to the Republican Party in the United States, which remains capable of disciplining Trump in myriad ways, the Brazilian armed forces, and the army in particular, has provided a necessary infrastructural bedrock for the Bolsonaro administration. Reflecting Brazil’s well-established sub-imperial role in the region – as much under the PT as under the rule of traditional bourgeois parties – many of the key military figures staffing the state since January have been drawn from personnel whose formative experience was Brazil’s occupation of Haiti, part of a wider mission of the United Nations.[121] Labelled ‘the Haitian Generals,’ this group has overseen the insertion of 103 military figures into the various strata of state apparatuses under Bolsonaro – from the vice presidency, to ministries, to federal banks, to municipalities, and to strategic state enterprises, such as Petrobras. [122]

According to a poll in early April, 60 percent of Brazilians consider the participation of military representatives in the Bolsonaro government to be positive. Apart from the president (himself an ex-army captain) and the vice president, representatives of the armed forces occupy six of 22 ministries, including Fernando Azevedo as defence minister. Two other ministers have had military training. Members of the army, airforce, and marines occupy dozens of positions of note in the current government. Exemplary cases are the head of the National Department of Infrastructure and Transportation (DNIT) and key positions within FUNAI. If the president’s most prominent, informal Twitter spokesperson is Carlos the pit bull, the formal position of chief spokesperson is occupied by General Rêgo Barros .[123]

While the social media warriors of Bolsonaro’s inner circle play a critical role in securing the otherwise exhaustible zeal of the grassroots, ‘the military ensures that this reality show does not undermine the functioning of the machinery of the state, and, therefore, of the government.’[124] Mourão presents himself as the face of institutionality in a government which loathes institutions, of good sense in a government which lacks it entirely, of equilibrium, in a government which sews uncertainty as a matter of course. In so doing, he has earned the special and concentrated opprobrium of Bolsonaro’s sons and their sage in West Virginia. However, to date, the pageantry of these melees has not translated into genuinely irresolvable conflict between the militarists and the cultural authoritarians.

On a recent trip to Washington, Mourão held a series of public events as well as closed-door meetings with US senators and the American vice president Mike Pence. US business representatives who met with him praised the general’s calm and firm temperament. Citigroup’s CEO for Latin America, Jane Fraser, for example, suggested that Mourão’s tranquil and firm comportment is a necessary ingredient for investor confidence in the Brazilian government. In his speeches to US investors, Mourão, in accordance with neoliberal technocrats, consistently defended the necessity of implementing radical pension and tax reforms, as well as wide-scale privatizations.[125]

As late as last year, it would have been difficult to imagine Mourão’s self-reinvention as a voice of reason and moderation. Until recently, he was generally seen as one of the most aggressive proponents of a return to military dictatorship after decades of democratic rule. The five-star general was pressured to resign shortly before he was fingered as Bolsonaro’s vice presidential candidate. He managed to miscalculate acceptable limits to open adherence to authoritarian rule during the late period of Dilma’s rule – ‘he had openly attacked Dilma’s government; declared that if the judiciary failed to restore order in Brazil, the military should intervene to do so; and floated the idea of an “auto-coup” by an acting president, should that be necessary.’ [126] Mourão, who is of indigenous descent himself, has berated the ‘laziness’ of Brazil’s indigenous population, has lamented the ‘trickery’ of the country’s descendants of African slaves, and has explained that the only reason his grandson is handsome is a consequence of the ‘whitening’ of the population through European migration.[127]

It is undoubtedly true that military-civilian relations changed with the return of liberal democratic rule in 1985. And yet, certain dark legacies of the way the democratic transition unfolded remain at play to this day. Unlike neighbouring Argentina, where the military was vanquished by the Malvinas/Falklands War and a resurgent popular movement for democracy, the Brazilian dictatorship ultimately collapsed as a result of internal disputes within the armed forces. There was no comparable popular insurgent pressure from below. Coming ‘from-above’ in this way, the nature of the transition has to some extent insulated the Brazilian armed forces from democratic accountability.[128] One reflection of this is the total autonomy enjoyed by the military educational system, of which Bolsonaro is a product.[129] The core history texts taught in these schools present the military coup of 1964 as a democratic revolution, carried out by moderate groups respectful of law and order. They omit entirely the assassinations, repression of human rights, and torture committed during the dictatorship.[130]

In recent years, the reach of the armed forces into civilian affairs has been extended. Beginning in the first administration of Dilma (2011-2014), the armed forces were assigned a major role in domestic policing tasks in the name of restoring public security. Under Temer (2016-2018), military influence grew further, with the reinstatement of ministerial status for the Cabinet of Institutional Security (GSI). The armed forces were also called upon to militarily intervene in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro between February and December 2018.[131] In the lead up to the October 2018 elections, various representatives of the armed forces let it be known, off record, that they would not accept another PT government.[132]

Although I have placed Bolsonaro firmly with the cultural authoritarians, he nonetheless shares many of the commitments of the militarists. For the first time since the end of the dictatorship, Brazil has a president who denies all evidence of the crimes committed by the military during the dictatorship, and who holds up one of the officials most associated with torture, Coronel Alberto Brilhante Ustra, as an exemplar for others. Bolsonaro is committed to a full alteration of the historical memory of the period, beginning with the idea that 1964 was not a coup, but rather a necessary initiative taken by the military in defence of democratic values.[133] Bolsonaro announced his intention to memorialize the fifty-fifth anniversary of the 1964 coup on March 25 early in his term, but was forced to back down in the face of public discontent.[134] According to Datafolha, the majority of the population (57 percent) continue to think the day inaugurating 21 years of dictatorship should be condemned. Thirty six percent of Brazilians nonetheless support the president’s efforts to rewrite history.[135]

Neoliberal Technocrats

Next to the cultural authoritarians and militarists, a third current of neoliberal technocrats has been central both to Bolsonaro’s rise to office, as well to the design of the government’s political-economic and anti-corruptions programs. The latter task has fallen to Sergio Moro, the ex-federal judge responsible for heading up the Lava Jato “carwash” investigations into corruption, which ultimately underpinned the impeachment of Dilma and the imprisonment of Lula.[136] After the first round of the 2018 elections, Bolsonaro brought Moro under his wing, promising him the ministry of justice and public security should he become president. Moro quickly became the most popular minister in the cabinet, recognized by 93 percent of poll respondents, and with an unmatched approval rating of 74 percent. [137] Moro’s fame is the product of his leading role in a carefully manufactured politicization of corruption investigations dating back to 2006. ‘Successive operations – raids, round-ups, hand-cuffs, confessions – were given maximum publicity,’ Anderson points out, ‘with tip-offs to the press and television, each carefully assigned a number (to date there have been 57, resulting in more than a thousand years of jail sentences) and typically a name chosen for operative effect from the cinematic, classical, or biblical imaginary.’[138]

While Moro’s public persona is one of dispassionate, judicious restraint, he happily assumed responsibility for one of the most reactionary pieces of legislation under Bolsonaro’s reign thus far. A package of anti-crime bills was passed into law under Moro’s watch with the ostensible aim of cracking down on endemic levels of violence. According to the new legislation, judges now possess the freedom to grant immunity to police officers who have killed civilians, provided the police officers can show that during the incidents in question they were subject to ‘violent emotion, excessive fear, or surprise.’ This is an extraordinary license to kill in a country where the number of annual police executions was already legendary.[139] According to the Brazilian Annual Public Security Report, in 2017, Brazilian police forces killed 14 people per day, 5,144 over the course of the year – a 20 percent increase relative to 2016. In 2017, 367 police officers were killed, an average of one per day. The uptick in police repression had no demonstrable effect on its purported aim, the reduction of homicides, of which there were 63,880 that year, 3 percent more than in 2016.[140] In 2018, with Rio de Janeiro’s favelas under military intervention at the behest of Temer, there were 1,532 officially registered killings by police. In 2019, the numbers have been equally impressive: 170 dead in January alone. After the apparent execution of 15 young men by police after they had been detained, Wilson Witze, the governor of Rio, immediately declared the police actions to have been legitimate.[141]

The anti-crime package overseen by Moro links back to an earlier presidential decree which freed up access to gun possession. In an intensely volatile combination, people have been granted even further access to guns while juridical freedom has been expanded such that vigilante assassinations can be framed as legitimate defence.[142] Despite everyday insecurity clearly having played a role in the election of Bolsonaro, recent polls indicate most Brazilians are unconvinced that the anti-crime package will actually improve their safety. For the majority of Brazilians, the possession of guns should be prohibited (64 percent), and society will not be more secure if people are better armed to protect themselves (72 percent). Police should not be free to shoot suspects because they might kill innocent bystanders (81 percent), and in instances where the police do kill, they should be investigated (79 percent). Pertinently, those police officers who shoot someone because they were in a heightened state of nervousness should be punished (82 percent).[143] Nonetheless, these polling figures have not translated into disapproval of Moro himself.

In a certain sense, Moro embodies the ideological conjoining of anti-corruption and state violence at the heart of Bolsonarismo. But he does so in a tempered voice, and with the measured, juridical rationality of the bourgeois state – a liberal cover for state murder. Moro is able to do so within Bolsonaro’s more general framework of rule. The president ‘consolidates in himself the program of the far-right, a program that focuses on corruption to give it legitimacy, and which focuses on a strong state, using the argument of violence,’ Saad-Filho explains. ‘But the idea is that if communities are insecure, more police and more violence will resolve this problem. A discourse that was connected to neoliberalism, again, because the state is intrinsically corrupt, so the way to resolve the problem of the state is to take it off the backs of the citizens through a neoliberal program. But you don’t talk about the program itself, you talk about liberating people from the yoke of a state which is intrinsically corrupt.’[144] Moro does the work of operationalizing this idea of a lean, hard, and clean state.

An agile operator, Moro is as comfortable in the sphere of social media, where he has plenty of followers, as he is in the more sedate corridors of power. He forges alliances with militarists in order to ensure the proper functioning of his ministry. At the same time, he obeys the diktats of Bolsonaro and his familial dynasty whenever necessary, and he avoids contradicting them publicly.[145] Should some kind of coup ever play out involving the removal of Bolsonaro and Mourão’s temporary seizure of the presidency, Moro would have been one logical candidate in the likely hasty search to follow, wherein an ex post facto civilian face would need to be found to legitimize the new regime.

But Moro’s luck recently ran dry. An anonymous source provided investigative journalists at The Intercept with a treasure trove of ‘private chats, audio recordings, videos, photos, court proceedings, and other documentation’ which reveal ‘highly controversial, politicized, and legally dubious internal discussions and secret actions by the Operation Car Wash anti-corruption task force of prosecutors, led by the chief prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol, along with then-judge Sergio Moro.’[146]The Intercept unleashed its first flurry of reports in early June, with many more apparently in the pipeline based on an archive of materials now in their possession (and also safely secured outside Brazil, should the government intervene).

The investigative reports published thus far indicate unambiguously that the Car Wash prosecutors were fundamentally motivated by the desire to prevent a return of the PT to power, and that Moro secretly collaborated with them on various fronts to ensure this outcome, even while presenting himself as a neutral arbiter of justice. This was long suspected by PT supporters and critics of the Bolsonaro government, but hard proof had been lacking until now.[147] ‘Telegram messages between Sergio Moro and Deltan Dallagnol reveal that Moro repeatedly stepped far outside the permissible bounds of his position as a judge while working on Car Wash cases,’ one of the published reports indicates. ‘Over the course of more than two years, Moro suggested to the prosecutor that his team change the sequence of who they would investigate; insisted on less downtime between raids; gave strategic advice and informal tips; provided the prosecutors with advance knowledge of his decisions; offered constructive criticism of prosecutorial findings; and even scolded Dallagnol as if the prosecutor worked for the judge.’[148]

There is also clear documentation in the journalists’ archives that Dallagnol had serious doubts about the basic constitutive evidence in the case against Lula, in particular whether a beachfront triplex apartment that Lula was accused of receiving as payback for dolling out multimillion-dollar contracts with Petrobras was actually Lula’s, and whether it in fact had anything to do with Petrobras (the latter being especially important jurisdictionally, because without the involvement of Petrobras the case could not have been tried by Moro in Curitiba).[149]

The significance of The Intercept findings is already clear as day, even if there are still many more stories to be published. Moro convicted Lula after clandestinely and illegally collaborating with the prosecutorial team at a time when Lula was leading in the polls of the 2018 presidential race by a wide margin. Only after Lula’s conviction and the PT’s switch to Haddad as candidate did Bolsonaro’s numbers begin to rise.[150] Without Moro’s actions it is very far from obvious that Bolsonaro would ever have been elected. ‘That the same judge who found Lula guilty was then rewarded by Lula’s victorious opponent made even longtime supporters of the Car Wash corruption probe uncomfortable,’ The Intercept journalists go on to point out, ‘due to the obvious perception (real or not) of a quid pro quo, and by the transformation of Moro, who long insisted he was apolitical, into a political official working for the most far-right president ever elected in the history of Brazil’s democracy. Those concerns heightened when Bolsonaro recently admitted that he had also promised to appoint Moro to a lifelong seat on the Supreme Court as soon as there was a vacancy.’[151]

However important Moro has been to Bolsonaro’s calculus of power, it was economist and financier Paulo Guedes who eased into place the unlikely marriage between the nationalist ex-captain and capital. Bolsonaro had exhibited no earlier sympathies for neoliberal economics, favouring state subsidies and protections for his military voting base when, as a congressperson, he occasionally assumed substantive positions. ‘In the sequence of Bolsonaro’s rise,’ long-time Brazil observer Peter Evans notes, ‘the figure of Paulo Guedes rivals that of Judge Sérgio Moro. If Moro and his judicial allies did the negative work of removing Lula, Guedes did the positive work of building capital’s confidence that Bolsonaro’s economic agenda would serve their interests.’[152]

Guedes was a co-founder of the largest private investment bank in Brazil, BTG Pactual, and has amassed considerable wealth. An authentic Chicago Boy, having received his doctoral training in the department of economics at the University of Chicago, Guedes’s clearest expression of unrestrained commitment to Milton Friedman’s monetarism was perhaps his move to Pinochet’s Chile in the 1980s to take up an academic post. It was in part the promise of a comparable union between liberal economics and authoritarian rule that drew him into Bolsonaro’s quest for state control. ‘People asked me,’ he explained to the Financial Times, ‘how can a liberal join conservatives? They will only bring disorder. But disorder is already here…. The president will bring “order,” the liberals “progress”,’ Guedes said, with reference to Brazil’s national slogan, ‘order and progress.’[153]