Marx, Engels & Theology: Roland Boer

Ecology & Marxism: Andreas Malm

Queer Marxism: Peter Drucker

Marxism & Cinema: Daniel Fairfax

The Left and COVID: A response to Mike Haynes

by Sam Friedman and Mary Jirmanus Saba

Mike Haynes’s article “The Left, COVID, and the Roads Not Taken” aims to skewer the Left for its failures during the COVID pandemic.[1] In this article, we first go through his argument and show its weaknesses and one or two strengths. We end by suggesting paths the Left can continue to take to centre the public’s health, including responding to the current, and future pandemics.

What Haynes said

Haynes begins his article by claiming that the pandemic is over, and that the disease is now endemic. We would be delighted if he were correct, in spite of doubts discussed below. Since he never defines “endemic,” we will do so, using a definition from Public Health Ontario:[2] “An endemic disease is one that is consistently present throughout a specific region or population. The prevalence of the disease remains stable and its spread is fairly predictable over time.” What Haynes does not discuss, or even mention, is that diseases can be endemic at very different rates of infection, disease, and death. For example, a disease could technically be described as “endemic” if it were reliably and predictably killing 10% of the population of the Earth each year. Luckily, COVID is not even remotely close to this. As of 2 January 2023, the peak of the last wave before we write this—but also, and crucially, a time before already limited reporting systems markedly deteriorated as governments around the world deliberately reduced and degraded their COVID data systems in order to return to “business as usual”—WHO reported a death rate globally of 40 thousand people per week.[3] As we begin to write this piece in September 2023, the world is facing another wave of infections and death. Yet governments worldwide have largely dismantled monitoring systems. According to the US CDC, for example, its reporting on provisional COVID deaths may not represent all deaths, and reporting delays may be “8 weeks or more.”[4] Still, COVID is still the fourth leading cause of death in the US, taking more than 250,000 lives in 2022 in the US alone. And as we discuss below, Haynes totally ignores Long COVID, which, at any given moment, seems to be at least temporarily causing serious health problems in millions of people in the UK, tens of millions in the United States, and far more globally.

To us, these data do not support Haynes’s characterisation of COVID as endemic, although there are many uncertainties about these data and trends. Worrisomely, the rate of viral evolution and the number of circulating variants remain high, which means that the predictability of spread and of death rates is low. (This challenges Haynes’ dismissal of it as endemic.) In any case, these high numbers, and the uncertainties around viral mutation and around Long COVID, belie the apparent complacency of Haynes’ article.

The thrust of Haynes’s argument is a critique of the “lockdown Left” and of the Left in general for failing to confront a number of issues and for having an insufficient presence in the politics of the pandemic. This critique is remarkably unfocused and, to our eyes, seems to be directed at unnamed strawmen. First, he never defines who or what he means by “the Left.” Secondly, he fails to identify who holds many of the views he attacks, with three exceptions: interestingly, in an article directed at criticising the Left in the UK, he mentions the late Mike Davis and Rob Wallace, both Americans, for not showing “any special insight that cannot be found in the many papers about the threat of pandemic disease produced by the thousands of people who work in the huge global disease surveillance networks”. To anyone who knows Wallace’s work or actions during COVID, this is absurd. Wallace’s keen insights into the roots of the pandemic in investment networks and decision-making, in relation to the logic of capital, are not widely presented in the surveillance networks, and Wallace’s practice as part of People’s CDC (which we discuss later) displays insights that Haynes seems not to have considered. The third person he criticises is also an American (who lives and works in the UK), Devi Sridhar, but it is not clear to us whether or why Haynes considers her of the Left.

Haynes is dead on correct in one of his arguments. The Left (at least as we use the term) does not have an adequate understanding of epidemiology or of public health.

Haynes spends considerable effort lambasting those on the Left who go “down the rabbit hole of elimination and the fantasy of zero COVID”. Unfortunately, he does not name anyone who actually held these beliefs. He could have concretised this by discussing what happened in Australia, New Zealand or China, and their varied attempts at COVID suppression. These attempts ultimately failed, in part because a suppression strategy cannot be pursued in one country alone. (In the case of China, certainly, we agree that maintaining public health was in part an excuse for state repression.) It did, however, succeed in holding mortality and illness rates far below those in the UK or the USA for some years.

Haynes argues that the class struggle was abandoned as well as much human interaction. We cannot judge if that was true of the Left in the UK. In the United States, this was decidedly not the case, at least after the last weeks of May 2020. Here, pretty much everyone on the Left was actively in the streets many times as part of the Black Lives Matter movement, for example, and later in the movement opposing hate crimes and stigmatisation directed at Asian Americans. Haynes may have “lived vicariously off a few protests of Black Lives Matter”, but, in the United States, the movement was organised and led to a significant degree by Black members of the Left. (Haynes’s frame here incidentally seems to exclude Black people from the Left). Furthermore, left activists, many of whom had been members of socialist groups similar to the SWP of which Haynes himself was an active member, were deeply involved in health workers’ protests and strikes at the lack of personal protective equipment during this same period of the pandemic (and since).

Haynes claims that “those on the Left who demanded vaccine mandates [should] be ashamed of their inability to make the elementary distinction between a vaccine that reduces the virulence of an infection and one that stops transmission”. Again, this argument fails to name anyone on the Left who was guilty of this, as well as ignoring the involvement of some left scientists in developing and testing the vaccines themselves. Rather, in the US, it is the US administration and its CDC which popularised such confusion (maybe Haynes is counting Rochelle Walensky in his broad sweep of leftists?). In the United States, our discussions of these issues were much more sophisticated. We discussed what the vaccine trials and subsequent research showed at considerable length, including the evidence that vaccination reduced both the probability of infection and that, by reducing the period of active infection, it therefore reduced the probability that an infected person would infect others. Now, it is true that those of us with an understanding of epidemiology were the ones who made these arguments, but we did so both as part of our efforts to teach the Left some of the basics of epidemiology and as a contribution to the politics of the pandemic. (We also note that Haynes does not report on what, if anything, he said on these issues.)

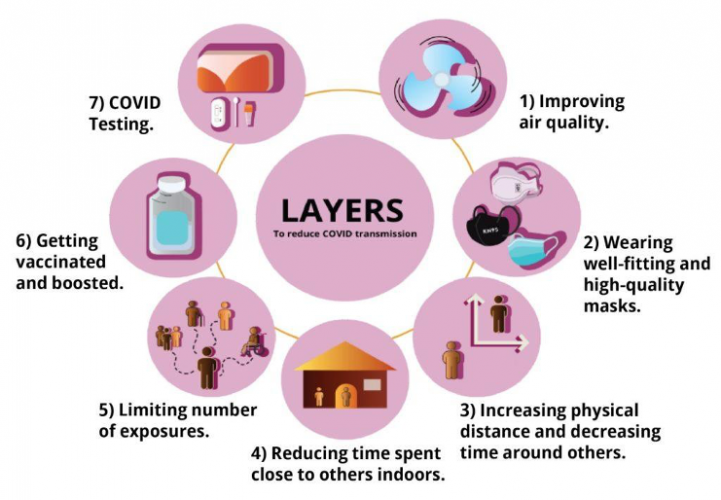

Haynes spends considerable effort attacking the view that mass testing could stop the pandemic. We actually know of no one on the Left who argued that in the US or the UK it would, although this argument was more viable for China and for New Zealand for reasons specific to those countries. Here, Haynes actually did name a name, Devi Sridhar, but does not tie her to the Left (which, admittedly, might not be needed for those readers of HM who live in the UK.) Also interestingly, Sridhar, as a professor of global public health, presumably does know something about epidemiology. We would add that the emphasis on mass testing and tracing in the US, at least, was mainly put forward by the CDC and by state health departments, not by the Left. Those of us in the People’s CDC, for example, have focused on layers of protection (which includes the availability but insufficiency of mass testing as a single tactic).

Haynes discusses risk transfer at some length, but these remarks seem to float in the air, since he does not cite any evidence that anyone on the Left held the views he criticises. Indeed, no one on the Left we know of actually held that the entire world economy should be locked down indefinitely. Nor did capitalists or actual governments do so, beyond the early weeks of the pandemic when the characteristics of COVID were still unclear.

Nevertheless, Haynes focuses on the concept of risk transfer—that wealthier people were protected and could stay at home whereas workers had to risk their lives. However, Haynes also writes, “Now you can, if you want, make an argument that this was necessary, and more lives were saved this way.” The implication is that he did not see it as needed—but he never states his alternative. In particular, he never discusses how workplaces and transportation to and from workplaces could have been made safer, nor does he mention the myriad ways that workers, from Amazon to Fedex to Target struggled for safer workplaces, an effort in which one of the authors of this piece was highly engaged. The same workers warned that bending public health measures for the country’s largest employer would lead to the market consolidation, which we’ve seen since. (We recall vividly a striking Amazon worker in Chicago in March 2020 waving a rubber chicken at a cell phone camera, asking if its purchase was “essential.”)

In addition, as Haynes and we argue, in most countries, many of those who stayed at home (to say nothing of capitalists!) gained in income whereas those who had to work outside of the home or who lost their jobs, lost. This is all true, and something we all opposed. Haynes then tries to make an argument that non-pharmaceutical interventions should have been “trialled” in the rich world. We would suggest that there are severe ethical barriers to doing this—how can you randomise people not to have good ventilation and filtration of air? Not to wear masks in situations where significant viral exposure might occur? Not to have greater spacing and other changes in meat packing factories? Practising public health researchers have long realised that certain interventions have so much face validity that randomised trials are not ethically feasible. In terms of HIV/AIDS, for example, it would have been unethical to exclude people who use drugs from obtaining sterile syringes or people engaging in high-risk sex from using condoms, which would be a necessary part of such a trial. In these circumstances, research has to rely on “natural experiments” and cohort studies, and a large number of these have been conducted for masks.

Haynes does present an alternative course of action for one circumstance: old people in end-of-life private care homes. Such facilities, along with prisons and some other forms of congregate living, were indeed the locations of horrendous and devastating outbreaks. And it was indeed a tragedy and, in some cases, a crime against humanity, that this took place and that people and their relatives were separated in their last days. Haynes proposes a solution to this: mobilising students and faculty as a care army to help out. He fails, however, to show how this would help. Wouldn’t it just mean that students and academics would carry the virus into and out of care homes rather than the staff of these facilities? Wouldn’t such a programme lead the owners of care homes to lay off the low-paid staff members to live on the dole and to rely on the labour of unpaid students and professors? Perhaps—and perhaps not. But Haynes does not seem to think through either the epidemiology or the social impacts of his solution.

Haynes then ends his article with what he called soul-searching questions.

What Haynes failed to discuss

Any article on the Left and the pandemic has to discuss the actual practice of the Left. Haynes does not do that, and we, as leftists living in the United States, do not learn from this article what left activists and researchers have done in relation to COVID. We want to present a few things that left activists have done in the United States, and suggest that members of the British Left probably took part in similar activities, even if Haynes does not mention it.

Before doing so, however, we want to make a caveat. Even more than in the UK, the Left in the United States is very weak, and has not yet fully incorporated analysis of public health and disability politics in the ways necessary to resist an ongoing, disabling pandemic. This is an essential point for reflection and future improvement.

In spite of these weaknesses, the Left took active part in the Black Lives Matter demonstrations and many subsequent related events. Indeed, to a large extent, Black left activists led many such events, as already mentioned.

Left activists took part in many workplace struggles for safer conditions. Most visibly, this was true in the huge healthcare and logistics industries Broad left leaderships of some unions like the Flight Attendants and some health-care unions also were very active in fighting for various mitigation efforts. Left teachers led or were involved in many struggles to force schools to take various mitigation measures before re-opening.

Many members of the US Left took part in safety and unionizing campaigns at work. Some of these were “salters”—that is, left activists who got jobs at a given workplace in order to organise there.

In early 2022, in a context where it was becoming daily more evident that the Biden administration was turning away from a public health approach to the pandemic and towards prioritising the profitability of business and the imperial interests of the United States, a combination of left activists including public health researchers, doctors, nurses, industrial hygienists, and lay leftists came together to form People’s CDC. The authors of this paper are all members, and leaders, of People’s CDC (as is Rob Wallace, whom Haynes criticised). We have emphasized mitigation efforts using “layered protection,” which are pictured in Figure 1.[5]

Figure 1. Layers of protection against SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19

People’s CDC has written and distributed documents criticising CDC’s response to the pandemic, a document on the Urgency of Equity that discussed ways to re-open schools more safely, a number of documents for worker and community groups on how to struggle to implement layers of protection, documents on how to gain access to medical interventions in the context of the US health-care non-system; and weekly issues of “Weather Report” and “COVID This Week” to help others keep abreast of the pandemic, policy towards the pandemic, and selected scientific issues. We have also organised thousands of public comments on health policy decision-making at various government institutions such as Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), and CDC’s ACIP and HICPAC, among others. Along with a coalition led by healthcare union National Nurses United and representatives from AFL-CIO, we have made progress pushing back on corporate influence on infection control guidance at the CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Policies Advisory Committee (HICPAC). And we’re just getting started (learn more and get involved at https://peoplescdc.org/.)

The authors of this article have engaged in many other forms of COVID-directed activity. Mary Jirmanus Saba was active in raising COVID safety demands in the Disability Caucus[6] and in the general strike movement during the weeks-long University of California 48,000 person strike in late 2022, demands which were later taken up, and won, by workers at the University of Michigan. Samuel R. Friedman[7] took part in planning strategies to protect harm reduction workers and people who inject drugs from both the virus and from social harms during the early part of the pandemic, and has written or co-written a number of left analyses including a critique of the left response to the pandemic in the USA, a critique of an establishment book, Lessons from the COVID Wars, an analysis comparing responses to the AIDS and COVID pandemics, and a number of articles in public health and epidemiologic journals.[8]

Haynes’s lack of engagement with active COVID politics shows in other ways as well. He fails to mention the ways in which, both during the clearly pandemic phases and more recently, during what he calls the endemic phase, inadequate mitigation and prevention measures have excluded whole groups of people from social activity in which others can participate. For example, relaxation of mask requirements and other mitigation measures have forced elderly people, disabled people and chronically ill people, as well as others who prefer not to risk Long COVID, to choose between a high risk of becoming infected and forgoing the use of public transportation, public schooling, and now healthcare (since CDC guidance has now led many hospitals systems to remove masking requirements.) Similar policies have essentially excluded many from safe access to their workplaces, and to many public events.

Unforgivably, for someone who touts his supposed epidemiologic expertise, Haynes nowhere mentions Long COVID, which has been described as a mass disabling event. In the United States alone, approximately 40 million people (as of mid-September 2023) have had Long COVID, which is over one ninth of the total population. At the moment, it is estimated that perhaps fifteen million people are suffering from Long COVID, and that many of them may do so for the rest of their lives. At any given time, millions are unable to work as a result. As of approximately the beginning of September 2023, among adults, 18% of women and 12% of men report that they have ever had Long COVID.[9] These startling numbers are likely an underestimate as they exclude people with asymptomatic infections. The UK Office for National Statistics reports that as of 5 March 2023, 1.9 million people living in private households (2.9%) had Long COVID, a number which excludes those in institutional care such as many elderly people, prisoners, and others.[10]

Summary

Haynes’s article gives the impression that COVID is under control and that the Left has played a sordid role throughout the pandemic. We are not so optimistic about the state of COVID. It still is infecting a lot of people, and large numbers of people are being incapacitated to a greater or less degree by Long COVID. Attempting to avoid illness is continuing to exclude large numbers of people from access to public life. Given the coordinated abandonment of mitigation efforts globally, and the continuing high global load of active infections, mutations are taking place at a rapid rate, and at best we can be cautiously optimistic that none of them will unleash another wave of massive death. Although we have not discussed it here, international comparisons of the impact of the pandemic make it clear that political incompetence—which often took the form of prioritising the profitability of capital over the health of the working class—probably is responsible for a sizeable proportion of the seven million deaths that WHO reports have resulted from diagnosed COVID globally (which is an undercount, given the number of excess deaths during this period).[11] All in all, then, the number of unnecessary deaths due to COVID—that is, those due to capitalist politics—are comparable in number to those due to genocides that receive massive attention from the Left. We, in People’s CDC, have attempted to make the politics of pandemics more visible to the international Left, to make the culpability of capitalism and colonialism in these horrors clearer to the public, and thus to strengthen the ranks of those who actively try to erase capital and to build an alternative world. We invite Haynes and others around this world to join us in these efforts.

Haynes fails to give any description of the actual activity of the British Left during the pandemic. We are based in the United States and lack the resources to provide such a description. Based on what the US Left has done in the pandemic, and our scattered communications with people in Britain, we seriously suspect that the Left in Britain has by no means been the abject failure that Haynes reports.

Nonetheless, Haynes’s article does make one important point with which we strongly agree: by and large, the Left has paid too little attention to epidemiology and public health. This is particularly true since the disruptions that climate change is already causing—and these will only increase during the lifetimes of those who read this article—are highly likely to undo whatever control humanity has managed to get over COVID, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, a host of other diseases, and perhaps additional emerging pandemics.[12]

[1]Haynes, 2023. https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/blog/left-covid-and-roads-not-taken

[2]https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/About/News/2022/Endemic(downloaded September 21, 2023)

[3]https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/apr/03/peoples-cdc-covid-guidelines

[4]https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_weeklydeaths_select_00

[5]Taken from https://peoplescdc.org/2022/09/12/layers-of-protection/ downloaded 9/24/2023

[6]https://truthout.org/articles/university-of-california-workers-center-disability-justice-in-union-organizing/

[7]Feldman, Justin; Friedman, Sam. Where is the Left on pandemic politics? Tempest. April 18, 2022. https://www.tempestmag.org/2022/04/where-is-the-left-on-pandemic-politics/

Friedman, S.; Kay, S. Marxism and the US Response to the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 Pandemics. August 25, 2023. Spectre Journal¸ web edition. https://spectrejournal.com/marxism-and-the-u-s-response-to-the-hiv-aids-and-covid-19-pandemics/

Friedman, S. https://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2023/07/05/learning-from-the-covid-war/

Sam Friedman. Fatal abstractions: Disease, death, and capitalist abstraction. Tempest Magazine 2023. https://www.tempestmag.org/2023/03/fatal-abstractions/

Friedman, Samuel R., David C. Perlman, Dimitrios Paraskevis, and Justin Feldman. 2023. Sociopolitical Diagnostic Tools to Understand National and Local Response Capabilities and Vulnerabilities to Epidemics and Guide Research into How to Improve the Global Response to Pathogens. Pathogens 12, no. 8: 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12081023.

Friedman SR, Jordan AE, Perlman DC, Nikolopoulos GK, Mateu-Gelabert P. Emerging Zoonotic Infections, Social Processes and Their Measurement and Enhanced Surveillance to Improve Zoonotic Epidemic Responses: A "Big Events" Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 17;19(2):995. https://doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020995. PMID: 35055817; PMCID: PMC8776232.

Frank D, Krawczyk N, Arshonsky J, Bragg MA, Friedman SR, Bunting AM. COVID-19-Related Changes to Drug-Selling Networks and Their Effects on People Who Use Illicit Opioids. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2023 Mar;84(2):222-229. PMID: 36971722 DOI: https://10.15288/jsad.21-00438

Walters, S.M., Bolinski, R.S., Almirol, E. et al. Structural and community changes during COVID-19 and their effects on overdose precursors among rural people who use drugs: a mixed-methods analysis. Addict Sci Clin Pract 17, 24 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-022-00303-8

Friedman SR, Mateu-Gelabert P, Nikolopoulos GK, Cerdá M, Rossi D, Jordan AE, Townsend T, Khan MR, Perlman DC. Big Events theory and measures may help explain emerging long-term effects of current crises. Glob Public Health. 2021 Aug-Sep;16(8-9):1167-1186. https://doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1903528. Epub 2021 Apr 11. PMID: 33843462; PMCID: PMC8338763.

Friedman, S.R. Environmental change and infectious diseases in the Mediterranean region and the world: an interpretive dialectical analysis. Euro-Mediterr J Environ Integr 6, 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-020-00212-9. NIHMSID: NIHMS1637417

Jenkins WD, Bolinski R, Bresett J, Van Ham B; Scott Fletcher; Walters S; Friedman S, Ezell J, Pho M, Schneider J, Ouellet, L. COVID-19 During the Opioid Epidemic – Exacerbation of Stigma and Vulnerabilities. The Journal of Rural Health, 2020. PMID: 32277731 PMCID: PMC7262104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12442.

Bunting AM, Frank D, Arshonsky J, Bragg MA, Friedman SR, Krawczyk N. Socially-supportive norms and mutual aid of people who use opioids: An analysis of Reddit during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 May 1;222:108672. https://doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108672. Epub 2021 Mar 18. PMID: 33757708; PMCID: PMC8057693.

Vasylyeva TI, Smyrnov P, Strathdee S, Friedman SR. Challenges posed by COVID-19 to people who inject drugs and lessons from other outbreaks. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020 Jul;23(7): e25583. https://doi: 10.1002/jia2.25583. PMID: 32697423; PMCID: PMC7375066.

[8]Feldman, Justin; Friedman, Sam. Where is the Left on pandemic politics? Tempest. April 18, 2022.https://www.tempestmag.org/2022/04/where-is-the-left-on-pandemic-politics/

Friedman, S. https://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2023/07/05/learning-from-the-covid-war/

Friedman, S.; Kay, S. Marxism and the US Response to the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 Pandemics. August 25, 2023. Spectre Journal¸web edition. https://spectrejournal.com/marxism-and-the-u-s-response-to-the-hiv-aids-and-covid-19-pandemics/

Friedman, S.R., Smyrnov, P. & Vasylyeva, T.I. Will the Russian war in Ukraine unleash larger epidemics of HIV, TB and associated conditions and diseases in Ukraine?. Harm Reduct J 20, 119 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00855-1

Friedman, Samuel R., David C. Perlman, Dimitrios Paraskevis, and Justin Feldman. 2023. Sociopolitical Diagnostic Tools to Understand National and Local Response Capabilities and Vulnerabilities to Epidemics and Guide Research into How to Improve the Global Response to Pathogens. Pathogens 12, no. 8: 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12081023Sam Friedman.

Friedman SR, Perlman DC, Paraskevis D, Feldman J. Sociopolitical Diagnostic Tools to Understand National and Local Response Capabilities and Vulnerabilities to Epidemics and Guide Research into How to Improve the Global Response to Pathogens. Pathogens. 2023 Aug 8;12(8):1023. https://doi: 10.3390/pathogens12081023. PMID: 37623983; PMCID: PMC10457759.

Friedman SR, Mateu-Gelabert P, Nikolopoulos GK, Cerdá M, Rossi D, Jordan AE, Townsend T, Khan MR, Perlman DC. Big Events theory and measures may help explain emerging long-term effects of current crises. Glob Public Health. 2021 Aug-Sep;16(8-9):1167-1186. https://doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1903528. Epub 2021 Apr 11. PMID: 33843462; PMCID: PMC8338763.

Friedman, S.R. Environmental change and infectious diseases in the Mediterranean region and the world: an interpretive dialectical analysis. Euro-Mediterr J Environ Integr 6, 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-020-00212-9. NIHMSID: NIHMS1637417.

[9]https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/long-covid.htmdownloaded 9/24/23

[10]https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/30march2023. Downloaded 9/24/23

[11]Friedman, S.; Kay, S. Marxism and the US Response to the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 Pandemics. August 25, 2023. Spectre Journal¸ web edition. https://spectrejournal.com/marxism-and-the-u-s-response-to-the-hiv-aids-and-covid-19-pandemics/

[12]Friedman, S.R., Smyrnov, P. & Vasylyeva, T.I. Will the Russian war in Ukraine unleash larger epidemics of HIV, TB and associated conditions and diseases in Ukraine?. Harm Reduct J 20, 119 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00855-1

Friedman, Samuel R., David C. Perlman, Dimitrios Paraskevis, and Justin Feldman. 2023. Sociopolitical Diagnostic Tools to Understand National and Local Response Capabilities and Vulnerabilities to Epidemics and Guide Research into How to Improve the Global Response to Pathogens. Pathogens 12, no. 8: 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12081023Sam Friedman.

Friedman SR, Perlman DC, Paraskevis D, Feldman J. Sociopolitical Diagnostic Tools to Understand National and Local Response Capabilities and Vulnerabilities to Epidemics and Guide Research into How to Improve the Global Response to Pathogens. Pathogens. 2023 Aug 8;12(8):1023. https://doi: 10.3390/pathogens12081023. PMID: 37623983; PMCID: PMC10457759.

Friedman SR, Mateu-Gelabert P, Nikolopoulos GK, Cerdá M, Rossi D, Jordan AE, Townsend T, Khan MR, Perlman DC. Big Events theory and measures may help explain emerging long-term effects of current crises. Glob Public Health. 2021 Aug-Sep;16(8-9):1167-1186. https://doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1903528. Epub 2021 Apr 11. PMID: 33843462; PMCID: PMC8338763.

Friedman, S.R. Environmental change and infectious diseases in the Mediterranean region and the world: an interpretive dialectical analysis. Euro-Mediterr J Environ Integr 6, 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-020-00212-9. NIHMSID: NIHMS1637417.

Nancy Fraser’s Cannibal Capitalism: An Extended Discussion

By Irina Herb, Dana Abdel-Fatah, Deborshi Chakraborty, and George Edwards

Nancy Fraser begins her most recent book, Cannibal Capitalism, by noting that the ‘current boom in capitalism talk remains largely rhetorical’.[1] Against this backdrop, the book seeks to equip a wider audience with an accessible framework to analyse ‘all these horribles’.[2] To do so, she upcycles and synthesises some of her earlier works, weaving them together through the metaphor of cannibalism which serves to symbolise capital’s undermining of its necessary background conditions.[3]

Closely following her earlier work,[4] Fraser starts the book with an accessible short introduction to the basics of an ‘orthodox’ account of Marx: studying the sphere of production, Marx finds that capital does not expand through the process of exchanging equivalents in markets. Rather, it expands in the process of production, when workers sell their labour-power to capitalists and do not get compensated for all of it(‘exploitation’). As she recounts, for Marx the preconditions for the capitalist mode of production were the violent processes of dispossessing/expropriating people of their means of subsistence and production during the ‘enclosures’ and formal colonialism (‘primitive’ or ‘original accumulation’). This created private ownership of the means of production, ‘doubly-free’ workers, ‘self-expanding value’ and the distinctive role of markets. Quoting Piero Sraffa, she characterises capitalism as a system for the ‘production of commodities by means of commodities’. However, she adds as a starting point for her discussion, ‘one that also relies, as we shall see, on a background of non-commodities’.[5]

From this point onwards, Fraser takes her readers beyond Marx and his scrutiny of ‘the hidden abode’ of production. She takes them to ‘abodes that are even more hidden still’ and ‘still in need of conceptualisation’. In this sense, her work may be seen as the ambitious attempt to fill ‘new volumes of Capital’[6] with a systematic account of the background conditions of possibility for exploitation. These conditions occur not only ‘outside the economy’, but function via logics different to those of the economy. The economy, with its front-story of exploitation and back-story of expropriation follows, as Marx himself had laid out, the logic of capital accumulation: power and resources are invested to produce commodities to be sold for surplus-value on markets. In the realm of unpaid social reproduction, in contrast, gendered ‘angels of the home’[7] in families and communities reproduce the worker without remuneration but driven by ideals of ‘care’, ‘mutual responsibility’, and ‘solidarity’.[8] The realm of politics provides the ‘public powers to guarantee property rights, enforce contracts, adjudicate disputes, quell anti-capitalist rebellions, maintain the money supply’.[9] The realm of non-human ecology provides resources necessary for production and a sink for its waste. Crucially, the functional differences and constructed boundaries between the economy and other ‘zones of non-commodification’, which run according to ‘distinctive ontologies of social practice and normative ideals’,[10] are no pre-capitalist relic but, in fact, fundamental to capitalism.

Based on such an ‘expanded notion of capitalism’, Fraser sheds a clarifying light on crises and processes of (de-)commodification: Rather than focussing on contradictions within the economic realm, she explains domination, destruction, and crises through the construction of boundariesbetween the economy and the non-commodified zones, which are specific to capitalist societies. Each of the realms, as well as racialised expropriation, is understood to stand in a contradictory but interdependent relationship with the economy. These ‘four “contradictions” of capitalism’ each ‘correspond to a genre of cannibalisation and embodies a “crisis tendency”’:[11] Capitalists depend on the non-commodified zones but are structurally pushed to deplete them. For example, capitalists are incentivised to keep the costs of social reproduction as low as possible – providing low standards of work protection, and legal means of tax avoidance – while equally depending on workers to be healthy (enough) to do the work. This contradiction, Fraser notes by drawing on Wallerstein, means that ‘capitalism is not characterised by pervasive commodification and monetisation, rather, commodification is far from universal and where it is present, it depends on zones of non-commodification’.[12]

After outlining her expanded notion of capitalism that conceptualises capitalism as consisting not only of the economy but also its background conditions, Fraser dedicates one chapter to each of them: expropriation, unpaid social reproduction, nature and the polity.

To Fraser, expropriation is ‘integral to capitalist society’[13] rather than an initial stockpiling of capital at the system’s beginnings (so-called ‘primitive accumulation’).[14] She argues that the concept of expropriation shines light on two phenomena: First, the fact that unlike as with exploitation, where ‘doubly free’ workers are paid only part of the value they produce, the concept of expropriation captures how land and labour-power continue to be stolen. The subjects of this theft are not random: According to her, the line between the ‘exes’ runs along the colour line. It is ‘their assignment to two different populations, that underpins racial oppression’:[15]white workers are exploited, whereas value is expropriated from racialised ‘dependent’ subjects.[16] Secondly, political orders enable such theft from racialised groups by legitimising and enforcing constructs like ‘chattels slaves, indentured servants, colonised subjects, “native” members of “domestic dependent nations”, debt peons, “illegals” and felons’.[17] In this sense, ‘the distinction between the two “exes” is a function not only of accumulation but also of domination’.[18]

With her conceptualisation of expropriation as mediated through racism, Fraser picks up on what she calls ‘a profound but underappreciated stream of critical theorising, known as Black Marxism’[19] that flourished between the 1930s and 1980s around figures like C.L.R. James, W.E.B. Du Bois, Stuart Hall, Walter Rodney, Angela Davis, Manning Marable, Barbara Fields and Michael Dawson, and has been reinvigorated by scholars such as Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Cedric Johnson, Barbara Ransby and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. Rather than positing racism as either necessary orcontingent to capitalism, Fraser claims that capitalism providesstructurally enabling conditions for racism and racial oppression.

After presenting the modality in which expropriation relates to exploitation in different historical regimes of racialised accumulation, Fraser concludes that in the present regime of financialised capitalism, in which private debt plays a pivotal role, the line between the two exes has become muddied. We now witness a new hybrid modality of the ‘expropriated-and-exploited citizen-worker. No longer restricted to peripheral populations and racial minorities, this new figure is becoming the norm.’[20]

In her chapter on unpaid reproduction as a background condition for the economy, Fraser notes a deep-seated contradiction or crisis tendency between capital accumulation and social reproduction.[21] Analogous to the periodic crises in the economy, we witness periodical ‘major cris[e]s – not simply of care, but of social reproduction in the broadest sense’.[22] In this context, the ‘division between social reproduction and commodity production is central to capitalism’:[23] parallel to the formation of the split between workers and capitalists, productive and reproductive work were split apart, the latter relegated to a separate, private, domestic sphere, obscuring its social importance and depriving it of remuneration in cash form. Through their association with it, women and feminised groups became structurally subordinated.

This contradiction has been tackled differently in different phases of capitalism: during the era of mercantile capitalism, reproduction in the core mainly continued to take place within households and churches, while in the ‘periphery’, social bonds were violently upended through looting, enslavement, and the dispossession of Indigenous people. In the liberal-colonial phase, women (and children) flocking into factories brought about a crisis of social reproduction and gender roles – a phenomenon famously and controversially commented on by Marx and Engels. This was managed by creating ‘the family’ in its modern restricted form. Drawing on Maria Mies, Fraser mentions the concept of ‘housewifization’ while also noting that poor, racialised and working-class women could never live up to the ideals of housewifery. As Fraser notes, this ‘struggle to ensure the integrity of social reproduction became entangled with the defence of male domination’.[24] In state-managed capitalism, the core dealt with the contradiction by enlisting state power in the form of welfare and the family wage, whereas social reproduction remained mainly beyond the purview of government in the periphery. In today’s financialised capitalism, new developments include divestment from social welfare, recruitment of women into the paid workforce and, resulting from that, a dual organisation of social reproduction: commodified for those who can afford it and privatised for those who cannot, with household debt and global care chains playing an increasing role.[25]

Fraser understands the natural world as a further noneconomic background condition for capitalist economies. ‘More than a relation to labour, capital is a relation to nature’,[26] Fraser insists. A capitalist economy depends on nature’s biophysical wealth to pile up value, but any responsibility for the ecological harms wrought – carbon dioxide flooding the atmosphere, islands of plastic rising from the seas, deforestation driving lethal pandemics – is routinely denied: ‘the damages are the flip side of profits’.[27] From the perspective of capital, nature is the ontological other of humanity, an infinite ‘realm of stuff, devoid of value’, but, in reality, the natural world is unable to self-replenish without limit. This predatory and extractive relation to nature thus leads to the eventual exhaustion of resources and destabilisation of ecosystems, a dynamic that in turn undermines capitalist society’s own ecological conditions of possibility. This, for Fraser, is ‘capitalism’s ecological contradiction’ – programmed as an iron law within the very structure of the economy.

Back in 1988, James O’Connor outlined this general schema as the ‘second contradiction of capital’, while in the spring of 2020, Andreas Malm[28] identified this theory as manifesting in crisis: with workers forced to shield themselves away from deadly pathogens, large parts of the economy ground to a halt. Yet the originality of Fraser’s contribution lies in the insistence that capitalism’s ecological contradiction cannot be isolated from the ‘system’s other constitutive irrationalities and injustices’.[29] The system denies social reproduction when it destroys life-sustaining ecosystems. It creates racially marked populations for expropriation when political powers enable resources to be extracted. Notwithstanding the divisions capitalist society enforces between the domains of economy, state, care and nature, Fraser maintains that all spheres are intimately connected, any one contradiction inescapably interacting with contradictions elsewhere. The central point being that we cannot fully anatomise capitalism’s ecological crisis without grasping the mutually interacting contradictions that constitute capitalist society.

Building on the concept of boundary shifts and struggles, Fraser aims to provide for the above abstractions a concrete form. From ox-turned mills to coal-fired industrialisation, through oil-fuelled automobility to carbon-traded ‘green capitalism’, she demonstrates the distinct ways in which each stage of capitalist development organised its relation to nature and managed its contradictions. Fraser endeavours to show not only how each ‘socio-ecological regime’ generated their energy and extracted their resources but also the concrete meanings that each regime ascribed to nature. To elaborate this latter point, Fraser wades into debates animating certain lines of ecological Marxism, as she tries to get a firmer grip on the ‘slippery’ term that is ‘nature’. She presents the reader with three natures: Nature I – a scientific-realist conception of nature as an objective force; Nature II – a structural analysis of the capital–nature relation – and Nature III – the object studied by historical materialism, concrete and changing over time. With ecosystems services, carbon-trading schemes and environmental derivatives now littering the capitalist imaginary, there is a green veneer to the inter-subjective beliefs that motivate the capitalist class (Nature II). But, whilst their actions may bring forth lithium mines or enclose lands for carbon credits (Nature III), very little will be done to tame the biophysical realities of global warming (Nature I). Whilst this tripartite schema of nature reminds us to remain vigilant against green illusions and technological fixes, it may be noted at this point that it is not clear what advances this somewhat clunky terminology offers to understanding beliefs about nature that a concept like ideology does not.

In her chapter on the polity as a background condition, Fraser outlines how, in capitalist societies, the economy crucially relies on public powers to guarantee property rights, enforce contracts, adjudicate disputes, quell anti-capitalist rebellions, and maintain the money supply.[30] In this context, she engages with the question of what causes the crisis of democracy and what its solution could be. She bluntly opposes what she calls ‘politicism’[31] – the liberal idea that the crisis is a consequence of the decline in the political ethos and the power of constitutional regimes. In this narrative, the solution is seen to lie within the political realm, an approach Fraser criticises for overlooking ‘extra-political society’.[32] While eschewing such liberal interpretations of the political crisis, Fraser also claims to avoid the ‘economism’ of past Marxists. In this line, Fraser’s fundamental contribution is her effort to connect the political crisis with the social, ecological, and economic crises.

Similar to Lenin’s attempt to understand the metamorphosis of capitalism from one avatar to another, Fraser outlines different stages of capitalism to understand the origin of today’s crisis. The current stage of capitalism is analysed through the prism of financialised capitalism where central banks and global financial institutions have become leading players[33] while simultaneously relying and freeriding on ‘public powers to establish and enforce its constitutive norms’.[34] These newly empowered global institutions have become sovereign in their function without being answerable to the public or the state, while their functioning is tremendously consequential to the public. To her, this conglomeration manifests itself in economic crises (e.g. Greece in 2015), political crises (e.g. Brazil in 2017–18), and the current refugee crisis.[35] Furthermore, Fraser argues that populism and populist regimes need to be understood as having come into power as a reaction to the onslaught of financialised capitalism. In this context, she criticises popular social movements for operating in the shadow of liberal hegemony, functioning as ‘junior partners of the progressive-neoliberal bloc’.[36] Precisely because of their previous and ongoing deep entanglement with neoliberalism, creating mistrust on the part of common working people, these movement failed to put up substantial opposition to the populist regimes.

Fraser ends the book by announcing the hope that ‘socialism is back!’, and goes on to advertise for it. Her vocal support for a socialist future certainly facilitates the mainstreaming and destigmatising of the discussions on socialism in academia. Apart from this zeal, however, Fraser’s book represents a theorem concerning today’s capitalist crisis rather than a manifesto for the future: her primary contribution is geared towards understanding capitalism and its crises. Therefore, when the reader turns to the chapter that promises to speak about ‘what we can do’, they should expect a short and limited intervention on socialism which side-lines some of the questions truly at stake. For example, the failure of twentieth-century socialism is often attributed to the lack of democracy and the hegemonic presence of the party in society and state functioning. Therefore, Fraser’s emphasis on the importance of inclusivity in decision-making is well-placed.[37] Yet, past socialist experiments have never disagreed in principle on the importance of inclusivity in the decision-making process, but nevertheless often failed on that score in practice. Therefore, at this point, a discussion of ‘what we can do’ will have to go beyond simply repeating calls for inclusivity. Here, thorny and nitty-gritty questions around the transformation to socialism (and the role of violence within it) and multiparty democracy in a post-revolutionary society remain to be discussed. Secondly, Fraser reiterates the classical socialist approach that a ‘socialist society must democratise control over social surplus’.[38] Yet, again, such attempts have failed in the past – for example in ‘Leninism’, where the state became the custodian of the surplus, which led to state capitalism rather than to the socialist redistribution of surplus – thus the debate on the ownership of surplus must go deeper, asking critical questions about the relationship between state and capital, including the state’s role in accumulating surplus and its redistribution.

Concluding Remarks

Fraser is not the first to claim that in capitalist societies the economy relies on ‘noncommodified zones’ such as unpaid ‘housework’, nature, the polity, and racism (as a mechanism to justify expropriation). Yet, surely, she may be credited for her attempt to bring disparate insights from older Marxist figures, including Karl Marx and Rosa Luxemburg, and newer voices from the realms of Marxist Feminism (Eli Zaretsky, Lise Vogel, Nancy Flobre, Barara Laslett, Johanna Brenner, Susan Ferguson, Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya) as well as figures from the ranks of eco-Marxism (James O’Connor, Jason Moore) together into one expanded notion of capitalism. Not only does her framework allow for connections between these different thinkers, it also helps elucidate political and strategic implications. This may be illustrated by way of an example: In Capital, Marx already drew on the example of a teacher to show that the same type of work (teaching) can occur both productively (in a private school) and unproductively (in a public school). Fraser now helpfully adds to the distinction between the productive and unproductive: her framework of different non-commodified zones is not only potentially easier to understand but also allows for more complexity than Marx’s binary distinction. In particular, it creates more space to theorise unproductive work commissioned by the state (care homes, childcare, etc.) – an important point of debates amongst Marxist Feminists. Furthermore, her framework helps us discern and politicise an important question: ‘In which realm should which work occur?’ ‘Moving’ activities from one realm to another shifts the boundary between these realms and therefore their size and power. To Fraser, these ‘boundary struggles’ are the ‘very stuff of social struggle in capitalist societies – as fundamental as the class struggles over control of commodity production and distribution of surplus value that Marx privileged.’ To her, they ‘decisively shape the structure of capitalist societies’.[39]

Two issues arise from Fraser’s framework that deserve further discussion.

Firstly, Fraser’s conceptualisation of different forms of oppression leaves room for debate. At a general level, the fact that she ascribes the particular types of domination respectively to each one of the (re-)productive spheres (plus expropriation) might be seen as a tempting proposition, since it appears to afford simple, clean answers – gendered oppression occurs in the realm of unpaid social reproduction, racism through the process of expropriation, ecological destruction within the realm of nature, and ‘political domination’[40] within the realm of politics. In doing so, she claims that her framework ‘brings together in a single frame all the oppressions, contradictions, and conflicts of the present conjuncture’.[41] Yet, unfortunately, the story of oppression is more complex – both with regard to questions of intersecting oppressions and with regard to forms of marginalisation that inevitably fall outside of her narrow framework. For example, readers may be surprised to find that queerness and queer-hatred hardly play a role, while ableism is not mentioned. These omissions are crucial – in particular, the case of queer-hatred would likely bring into question the idea that each form of discrimination fits neatly within a single box.

More specifically, Fraser’s emphasis on expropriation to conceptualise racism has certainly added to the debate in important ways. Yet, it should be discussed whether her use of the concept may be doing both too much and too little at the same time. Too much in the sense that it is dubious whether the ‘two exes’ are really fit to do as much of the analytical lifting to explain racism as she seems to suggest: Expropriation does not seem sufficient to explain racism in all its different historical and global formations, not to mention its relationship with other categories like religion, ethnicity, or caste. It is also worth remembering that the US American case, which Fraser appears to prioritise, does not translate easily to other contexts. Furthermore, Fraser’s heavy reliance on the concept of expropriation to capture the theft of land and labour from racialised groups and to motivate political orders, comes at the cost of neglecting important superstructural factors, including the ideological dimension of racism.[42] In addition, it seems unclear to what extent her explanation of racism holds today: After discussing the blurring line between the two exes in the current regime of financialised capitalism, Fraser rightly asks, ‘why does racism outlive the disappearance of the sharp separation of the two exes?’[43] Yet, this question remains largely unanswered, left as an exercise for future discussions: How can we conceptualise racialising dynamics in financialised capitalism? What are the political and social implications of the conflation of the ‘two exes’? Does Fraser’s model appropriately capture the past but fall short in explaining racialisation processes in the present? Or is there a deeper underlying issue that renders her model questionable more generally?

Fraser’s application of expropriation may do too little in the sense that it is empirically and conceptually unclear why she restricts the reach of expropriation to explaining racism, rather than domination and oppression more generally. For example, women have been, and at points continue to be, legally excluded from voting, certain forms of work or holding their own bank accounts.[44] Fraser herself discusses how patriarchal legislation (accompanied by norms) has rendered women vulnerable to conducting unpaid ‘housework’. Here, she not only seems to court a logical contradiction when she refrains from using the concept of expropriation in the context of patriarchy. She also curiously omits Federici’s and other feminists’ argument that before there was the expropriation of the land, there was the expropriation of the female body.[45]

Taking into account that, in a later chapter, Fraser turns to expropriation to make sense of ecological destruction,[46] it seems apt to ask: could there be a larger conceptual issue concerning expropriation in Fraser’s overall framework? It is at least noteworthy that Fraser seems to conceptualise expropriation on a par with the realms of nature, social reproduction and polity as ‘non-economic normativities’[47] which serve as background conditions to the economy. Yet, nature, social reproduction, polity, and economy are realms within which (re-)production occurs, whereas exploitation and expropriation describe the mode of non- or under-compensation. In this sense, rather than conceptualising expropriation as occurring adjacent to the non-commodified zones, we should discuss whether expropriation ought to be conceptualised as occurring within the economic realm,between the economy and its background conditions andwithin the realms of the background conditions.

Secondly, what is an anti-capitalist struggle? Against the backdrop of her contention that the economy depends on non-commodified zones, Fraser states that ‘what counts as an anti-capitalist struggle is thus much broader than Marxists have traditionally supposed’.[48] While this is certainly a valid (albeit not a new) point, a problem arises: She eschews the truly tricky question of which struggles are anti-capitalist and which prolong its life. At points, the reader might get the impression that any struggle is anti-capitalist, given that it may undermine the background conditions of the economic sphere. More prominently though, Fraser offers a scathing critique of those movements which have failed to be anti-capitalist in their struggles. She understands them to serve as ‘front men […] by casting a veneer over the predatory political economy of neoliberalism’. This ‘unholy alliance ravaged the life conditions of the vast majority and thereby created the soil that nourished the Right’.[49] She furthermore criticises ‘that romantic view [which] is held today by a fair number of anti-capitalist thinkers and left-wing activists’ who ‘too often […] treat “care,” “nature,” “direct action,” “commoning,” or (neo) “communalism” as intrinsically anti-capitalist’.[50] From our perspective, the point here is not to dismiss her critique of romanticised (and oftentimes depoliticised) ideas of anti-capitalism. Rather, the point is of an analytical and pragmatic nature: how far will activists get when they learn that some forms of activism are ‘too romantic’ or too ‘neo-liberal’ and yet are unable to learn what actually constitutes anti-capitalist struggles? Here, Fraser unhelpfully downplays a question which has been and still is hotly debated: how do struggles get co-opted? And when is care-work in non-commodified zones, which is at times associated with anti-capitalist resistance, accidentally propping up and perpetuating the system by keeping its background conditions running? When could non-commodified zones serve as pockets for resistance and foster the formation of alternatives?

To conclude, Cannibal Capitalism should not be missed by anyone who is interested in making sense of current crises. It is also a must-read for those involved in analytical debates on overarching Marxist frameworks which synthesise work on social reproduction, racism, the state, and ecology.

References

Bhattacharya, Tithi 2017, ‘Introduction: Mapping Social Reproduction Theory’, in Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression, edited by Tithi Bhattacharya, pp. 1–20, London: Pluto Press.

Cooper, Melinda 2017, Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism, New York: Zone Books.

Federici, Silvia 1975, Wages against Housework, Bristol: Falling Wall Press/The Power of Women Collective.

Federici, Silvia 2004, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, New York: Autonomedia.

Ferguson, Susan 2020, Women and Work: Feminism, Labour, and Social Reproduction, London: Pluto Press.

Fraser, Nancy 2014, ‘Behind Marx’s Hidden Abode: For an Expanded Conception of Capitalism’, New Left Review, II, 86: 55–72.

Fraser, Nancy 2022, Cannibal Capitalism: How our System is Devouring Democracy, Care, and the Planet – and What We Can Do About It, London: Verso.

Fraser, Nancy and Rahel Jaeggi 2018, Capitalism: A Conversation in Critical Theory, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Luxemburg, Rosa 1975 [1913], Die Akkumulation des Kapitals. Ein Beitrag zur ökonomischen Erklärung des Imperialism, inGessamelte Werke, Bd. 5., Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

Malm, Andreas 2021, Corona, Climate, Chronic Emergency: War Communism in the Twenty-First Century, London: Verso.

Marx, Karl 1974 [1857/1858], Grundrisse der Kritik Der Politischen Ökonomie, Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

Morgenstern, Christine 2002, Rassismus – Konturen einer Ideologie.Einwanderung im politischen Diskurs der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Hamburg: Argument Verlag.

Müller, Jost 2002, ‘An den Grenzen kritischer Rassismustheorie. Einige Anmerkungen zu Diskurs, Alltag und Ideologie’, in Konjunkturen des Rassismus, edited by A. Demirovic and M. Bojadzijev, pp. 226–45, Münster: Verlag Westfälisches Dampfboot.

[1] Fraser 2022, p. 1.

[2]Fraser 2022, p. xii.

[3]Fraser 2022, pp. xiii–xiv.

[4]Fraser 2014; Fraser and Jaeggi 2018.

[5]Fraser 2022, p. 5.

[6]Fraser 2022, p. 8.

[7]Fraser 2022, p. 61.

[8]Fraser 2022, p. 18.

[9]Fraser 2022, p. 12.

[10]Fraser 2022, p. 20.

[11]Fraser 2022, p. 24.

[12]Fraser 2022, p. 18.

[13] Fraser 2022, p. 33.

[14] Fraser 2022, p. 36.

[15] Fraser 2022, p. 29.

[16] Fraser 2022, p. 36.

[17] Fraser 2022, p. 33.

[18] Fraser 2022, p. 37.

[19] Fraser 2022, p. 27.

[20] Fraser 2022, p. 47.

[21]Fraser 2022, p. 54.

[22]Fraser 2022, p. 53.

[23]Fraser 2022, p. 9.

[24] Fraser 2022, p. 60.

[25] Fraser 2022, p. 68.

[26] Fraser 2022, p. 83.

[27] Fraser 2022, p. 83.

[28] Malm 2021.

[29] Fraser 2022, p. 90.

[30] Fraser 2022, p. 12.

[31]Fraser 2022, p. 115.

[32]Fraser 2022, p. 115.

[33]Fraser 2022, pp. 127–8.

[34]Fraser 2022, p. 119.

[35]Fraser 2022, p. 131.

[36]Fraser 2022, p. 136.

[37]Fraser 2022, p. 153.

[38]Fraser 2022, p. 154.

[39]Fraser 2022, p. 21.

[40]Fraser 2022, p. 25.

[41]Fraser 2022, p. xv.

[42] See for example: Morgenstern 2002; Müller 2002.

[43] Fraser 2022, p. 49.

[44] For example, West German married women required their husband’s written consent to join the workforce until 1977 and to hold a bank account until 1958. In some countries similar arrangements remain in place until today.

[45] Federici 2004.

[46] Fraser 2022, p. 89.

[47] Fraser 2022, p. 18.

[48]Fraser 2022, p. 25.

[49]Fraser 2022, p. 136.

[50]Fraser 2022, p. 22.