Monism and Difference: A Review of A. Kiarina Kordela’s Epistemontology

France: Without Struggles, No Popular Front. Six Theses for a Discussion

If, at the top of the state building, they play the violin, how can we not expect those at the bottom to start dancing?

Gaza: 7 October in Historical Perspective

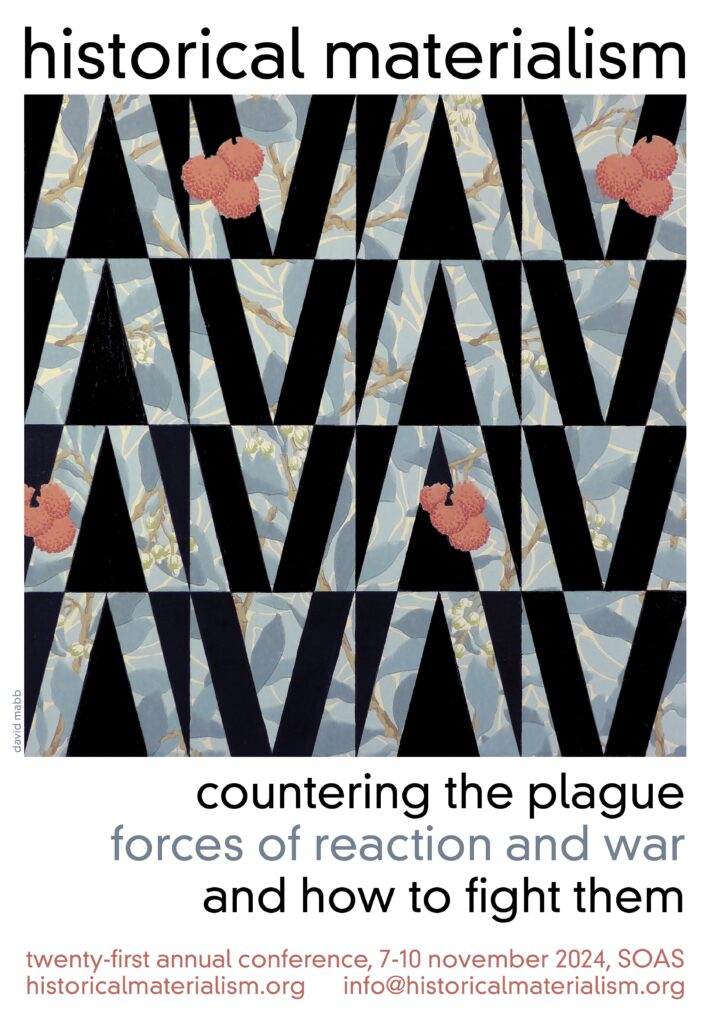

Post-Capitalism Stream Call for Abstracts – Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

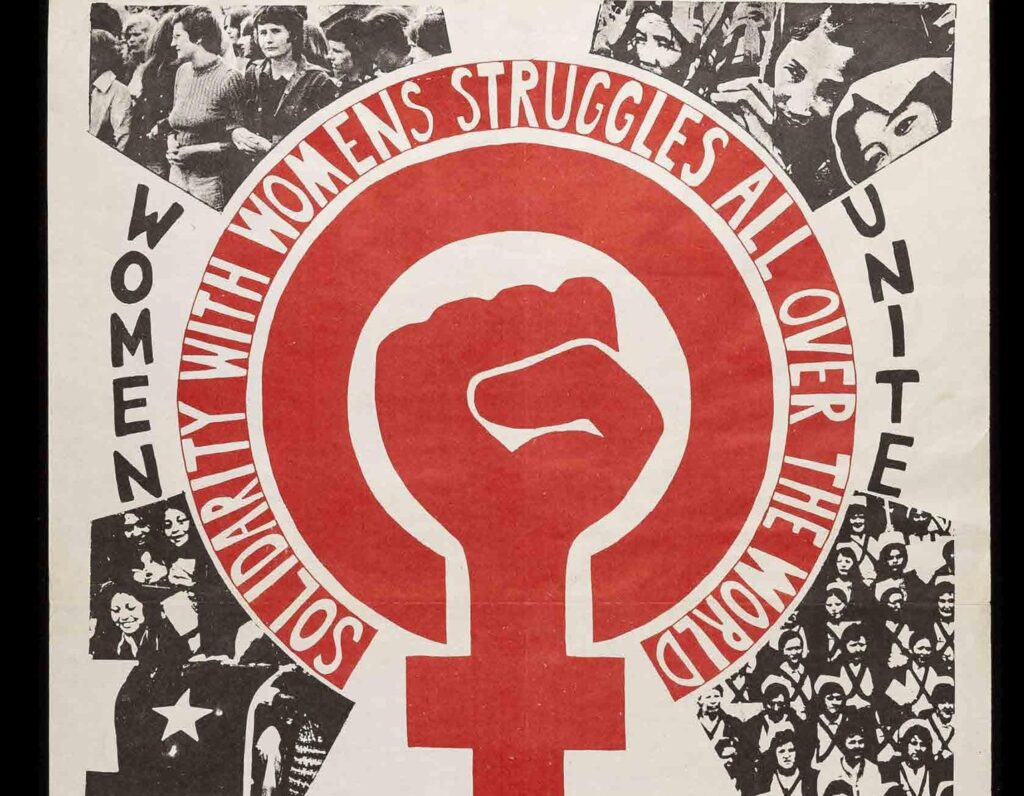

Marxist-Feminist Stream Call for Abstracts – Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Historical Materialism London 2024: Postgraduate Conference Invitation

Marina Vishmidt, 1976-2024

Marxism and Culture Stream Call for Abstracts – Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Sexuality and Political Economy Stream Call for Abstracts: Strategies for Free and Emancipatory Sexualities

Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Western Marxism Stream Call for Abstracts – Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

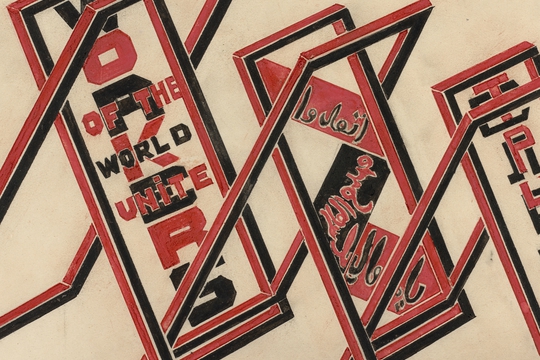

Workers’ Inquiry Stream Call for Abstracts – Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference

Twenty-First Annual Historical Materialism London Conference