What is the Traditional Working-Class?

The Problems of Tradition

By Alex Maguire

To paraphrase Marx who, like Lucifer, has all the best lines: a spectre is haunting political discourse – the spectre of the Traditional Working-Class. By Traditional Working-Class (TWC) I do not mean the class itself, instead I mean the typical concept and collection of common misunderstandings that underpins the popular understanding of this class. In the years since the 2016 Brexit Referendum, the term ‘Traditional Working-Class’ has become endemic in political and cultural discourse in Britain.1 Prior to this the term was seldom used, though it did exist as a category in the BBC 2013’s class survey. The term is now probably the most used class descriptor in common discourse (its only rival would be ‘white working-class’ which is used either as a pejorative or a badge of honour); however, it has not been defined who and what this class are. What is this class’ relationship to production, consumption, and other classes? Does the TWC exist, and if so where? What precisely makes them traditional, and what are these traditions? It is necessary to investigate these questions to properly understand what precisely this class is. It should be emphasised that interrogating the concept of the ‘traditional working-class’ is not the same as interrogating working-class traditions. The English working-class has a rich and varied history of traditions. This is indisputable. What is open to question is the precise nature of the TWC.

There have been substantial changes in the material reality of working-class life, and, just as the concept of tradition must be investigated, material changes must also be recognised. There have been substantial demographic changes in many of England’s communities in the last fifty years, capitalism has provided new industries such as platform and call centre work, and working conditions have rapidly declined in the last ten years. The working-class looks quite different today than it did thirty years ago.

In the face of these changes, a common construction of the TWC is that it resides in ex-industrial and mining towns in the North,Midlands, and South Wales, is largely comprised of white male labourers, skilled or unskilled, and is often ignored by metropolitan society. The precise geographic location of this construction is largely a product of Labour’s 2019 electoral defeat in many of these constituencies, and partly accounts for the distinctly English character of this class, even if occasional acknowledgements are made of the impacts of deindustrialisation on towns and villages in Wales.2 This is a glib description that has taken root on both the right and the left. This construction marginalises women, ethnic minorities, and the working-class located in urban centres, particularly those associated with the new industries of the inter-war period, such as electronics and electrical engineering, vehicle construction, chain retailing and bulk clothing production, artificial fibres, aviation, cinema in places such as Coventry and Oxford. While not all uses of this term are as simplistic, most are.3

The description used for the Great British Class Survey is equally problematic. Mike Savage et al. argue that one of the defining characteristics of this class is that ‘old-fashioned’ occupations such as lorry driver, cleaner, electrician, and factory worker, are over-represented in its number. Effectively, they are arguing that these jobs are traditional working-class jobs. ’.4 However, Savage et al. argue, class is not just the job one does, but the specific labour relations that are part of that job. These labour relations are the social relations of production. The authors go on to state that:

‘we might see this class as a residue of earlier historical periods, and embodying characteristics of the TWC. We might see it as a “throwback” to an earlier phase in Britain’s social history, as part of an older generational formation’.

When history is invoked, it must be asked who is invoking it, why are they invoking it, and which specific construction of history are they invoking. Furthermore, the specific notion of tradition is a historically difficult term. Hobsbawm noted that traditions ‘which appear to claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and sometimes invented’.5 While all traditions are at some point invented, and most enjoy liberal relations with historical veracity, unlike Hobsbawm’s traditions, the TWC has not been ascribed a delineated set of actual tradition (such as a common dress sense akin to the early twentieth century ubiquity of the flat cap). Instead, ‘traditional’ is a collection of common ideas that individuals ascribe to and identify, even if these ideas are not materially grounded. Indeed, Hobsbawm observes that the recently invented notions of tradition tend to “be quite unspecific and vague as to the nature of values, rights and obligations of the group membership they inculcate’.6 Perhaps it is this vagueness that has made the TWC such a potent rhetorical device.

To better underline what I think the problems with the concept of the TWC are, I shall provide a brief definition of what I think the English working-class is. The working-class has always constituted an array of relationships and employment conditions. After all, no class is homogeneous and the working-class is made up of different overlapping fractions with their own nuanced relations to production. It is the relative precariousness of these fractions that ensures they regularly overlap. As Satnam Virdee wrote, the ‘labour process imparts on [the working-class] a fractional character, which, in turn, means that at any one moment in time, the class consciousness of the aggregate working class is unlikely to be identical’.7 The English working-class is large and, in some instances, has a significant liminality with parts of the middle-class in terms of relation to production and income. An example of this is how most of the NHS’ junior management is drawn from the shop-floor, meaning that staff are promoted from engaging in production to managing production. Equally, a few high earning members of the labour aristocracy, such as very successful self-employed plumbers and carpenters, will be able afford a middle-class quality of life and often live-in middle-class neighbourhoods. In this sense, the TWC differs from a class such as the British landowning aristocracy which is small enough to regulate entry and can selectively reproduce itself.

The overlapping fractions that constitute the bulk of the English working-class (excluding children and retired pensioners) are: the proletariat, labour aristocracy, organised labour, unorganised labour, wage labourers (who’s employment may be relatively stable but is still tied to a wage), and unpaid domestic labourers. Indeed, throughout their lives, most members of the working-class will have been part of many, and some even part of all, of these fractions. This list is by no means complete, and while it is possible to identify other groups, I think that these categories account for the majority of the working-class and sufficiently illustrate the nuances of this class’ internal relationships. I define the proletariat as being the part of the working-class whose employment conditions are characterised by insecurity, and therefore their employment conditions (though not their culture, sense of class, and assets) may have more in common with some precarious members of the middle-class, for instance actors, than other members of the working-class.8

The term labour aristocracy requires clarification. I do not mean it in the Leninist sense, which refers to the working-class of the western world who benefited from the spoils of nineteenth and twentieth century imperialism. I use the term to describe a group similar to Hobsbawm’s Labour Aristocracy who are ‘better paid, better treated and generally regarded as more “respectable”’, though I reject Hobsbawm claim that this group is innately more politically moderate than the ‘mass of the proletariat’.9 The labour aristocracy are the ‘upper strata of the working class’ who have more control over their processes of production, on account of their skilled labour, which better enables them to navigate the working day.10 Richard Price provided a good description of the Labour Aristocracy when he wrote:

‘the labour aristocracy may be seen not as a fixed group, dependent upon a certain kind of industrial technology or organization, but as encompassing those who were able to erect certain protections against the logic of market forces on the basis of the spaces provided by aspects of segmentation. Thus, to admit the many lines of segmentation within the working class is not to dispose of the problem of the labour aristocracy; it is, rather, to drive it back to its original location in the sphere of production. A fundamental line of cleavage within the working class is between those who are able to realize some protections against market vulnerability and those who are not. In the mid-nineteenth century, this cleavage attained a particular importance and prominence because, in the absence, for example, of political democracy, it provided one of the few ways by which sections of the working class could assert their influence and self-conscious identity in society.’11

As a result of this privileged relation to productive forces, usually on account of possessing specific skills, the labour aristocracy has often organised itself into craft unions. These craft unions, for instance the Fire Brigade Union, Bakers Unions, and the Associate Society of Locomotive Engineers and Fireman, until the rapid reversal of the forward march in the eighties, exerted considerable control over the labour market as they were able to regulate the supply of labour by regulating entry into their specific craft. Although this still exists in part, the trajectory of trade unions in the United Kingdom is towards general unions, for instance UNISON, Unite, and GMB, meaning that the labour aristocracy may continue to decline.

Organised labour means workers who are part of labour organisations, most importantly trade unions, while unorganised labour means those who are not. Even within the distinction of organised labour there are further divides: some trade unions may be open (general) while others may be closed (craft) unions. Not all these categories are mutually exclusive, and some will go hand in hand, for instance a labour aristocracy operating a closed union, but they are useful distinctions to keep in mind. Thus, it is evident that even the supposed traditions of a class are complex and varied, and this is before the splits between the workplace, the home, and public life are taken into account. Therefore, ascribing one group as the sole TWC, without accounting for the different social relationships that define this class, is a flawed exercise.

While it is important to note the distinctions between different types of working-class existence, it is equally important not to become lost in these distinctions. Edward Thompson argues that:

‘“Working classes” is a descriptive term, which evades as much as it defines. It ties loosely together a bundle of discrete phenomena. There were tailors here and weavers there, and together they make up the working classes.”12

This is where it is important to draw the distinction between the objective situation of a class and a groups’ subjective awareness of its situation. While it is true that many people consider themselves/are considered to be part of the TWC and, if coverage of the 2019 General Election is to be believed, voted for the party they believed best represented them, their relations to production have too little in common for them to be considered a class.13 The act of self-identifying as part of a class is not enough in and of itself to qualify for class membership.

As highlighted above, the historical construction of the ‘traditional’ omits many groups of people from working-class history, and particularly women, immigrants, and the urban working-class. It also too often ignores the traditions of workers’ organisation. All of these have been integral to the English working-class since its inception. Even if these omissions are not conscious or deliberate, they are significant. Too often the historical and current importance of these groups is not sufficiently expressed. It is not enough to avoid their exclusion, instead their historical significance should be actively highlighted.

Tradition’s Omissions:

A women’s place?

Too often there is the underlying assumption that women do not work and are exclusively what Richard Hoggart termed “the pivot of the home”.14 While the significance of working-class women to the family and the home, either as single mothers or as part of a partnership, is often noted, their status as workers is too often ignored. While the unpaid domestic labour of working-class women has, as noted by Lisa Vogel, been integral to the social reproduction of the working-class, the nature of this socially reproductive labour is disputed. Some, such as Vogel, argue that it is ultimately unproductive labour as it does not generate surplus-value, while others such as Sylvia Federici and Alessandra Mezzadri have exposed the potential limitations in Marx’s theory of value and argued that, in Federici’s words, ‘those who produce the producers of value must be themselves productive of that value’.15 The scope of this debate, interesting and challenging as it is, is beyond the parameters of this article.16 What I want to highlight is that working-class women, as well as undertaking vital unpaid domestic labour, have always functioned as conventional workers selling their labour power.

Work is a fundamental part of working-class life; as long as the working-class has existed working-class women have been workers. However, working-class women have often been much more limited in how, and the extent to which, they sell their labour power. They have typically had to navigate more complex and arduous relationships with production and capital. This makes their contribution to the development of the working-class particularly important as it adds a different and more complicated dimension to the formation of this class.

Perhaps the underlying assumption about working-class women and work has not been helped by famous historical texts, such as The Making of the English Working-Class, which fail to adequately account for the role of women in this process. For example, in the nineteenth century many working-class women worked as domestic servants. Laura Schwartz notes how research conducted by Leonore Davidoff demonstrates that a gendered division of labour relegated women’s economic activity to a theoretical private sphere, resulting in domestic labour (the majority of which was female) being devalued and regarded as unproductive, even though this low paid domestic labour was integral to nineteenth century capitalism and social reproduction.17 Schwartz also highlights that servants were excluded from Marx’s analysis of contemporary capitalism. Since their work was viewed as unproductive they were considered unimportant to the development of the working-class. 18

However, women were not solely engaged in domestic labour, whether paid or unpaid, in the nineteenth century. Many women and children worked in the textile industry, and still do today in sweatshops across the globe. In this industry, they had a more straightforward relation to production and the creation of surplus value. The experiences of these women are still often ignored in the descriptions of the TWC, which consistently situates women in the home, and focusses on an almost fetishised construction of the male worker. Textiles as an industry is an interesting case study. It is the one major industry from which women (and children over 12 with a ‘leavers certificate’) were not excluded by male unions/legislative provision, perhaps because of its relative ‘domestic’ nature.

Women’s work being theoretically, if not practically, relegated to the home (despite the brief interruption of the First World War) continued into the twentieth century. This does not mean that women did not work, just the opposite in fact. Dolly Wilson points out that, prior to the growth of part-time women workers in the post-war period, as many as 40% of women in Edwardian working-class communities were engaged in petty home-based capitalism.19 Their economic activities included washing, child-minding, and selling homemade food and drink, and were part of ‘the underground economy of sweated labour, casual and home-work’.20

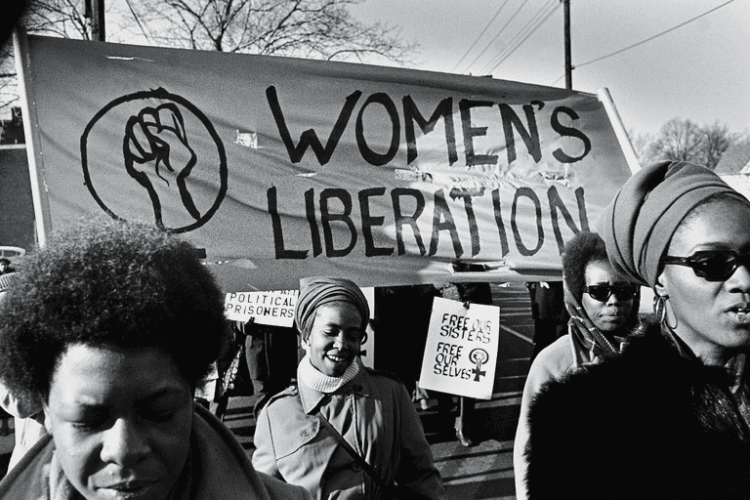

Even though in the post-war period the work done by working-class women has become more visible, as some moved away from the shadow economy and into the recognised labour market, they are not typically recognised as working-class workers. This is despite active participation in the labour movement, and multiple high profile industrial disputes, the most famous of which are probably the successful 1968 Ford sewing machinists strike that lead to the 1970 Equal Pay Act, and the unsuccessful Grunwick dispute in 1976.

Although, as Johnathan Moss notes, women ‘presented themselves on the labour market on different terms to men’, they have still indisputably been an active part of the working-class and organised labour since 1945. Any conception of the working-class that does not take into account that not only have working-class women always worked, but also that they have often experienced distinct and more arduous conditions of employment, is counter-productive to recognising the many facets of working-class existence and experiences. 21 Moss also argues that labour force participation in this period ‘was often experienced or viewed as claim to political citizenship’. Just as engaging in industrial disputes proved that working women were political citizens, it can also be interpreted as demonstrating that women were fully conscious and active members of their class, as this participation highlights that industrial militancy was not just the preserve of men22

The tradition of working-class women working has continued in the twenty-first century, their position in the labour market has become more entrenched, so it is odd that they are often tacitly excluded from the descriptions of ‘traditional’ workers. The improved (though by no means perfect and now worsening) position of working-class women in the labour market is the outcome of an important tradition of struggle. Women are also now more established in the labour movement and are responsible for 57% of Britain’s trade union membership.23Indeed, in the sixties and seventies they accounted disproportionately for the rapid increase in union membership. However, an indication of how far they still have to go is that UNISON, with a membership of 80% women, has only just elected its first female general secretary: Christina McAnea, who was born into a working-class family in Glasgow.

Furthermore, the current pandemic has highlighted the amount of working-class women that are key workers (largely as a result of women being concentrated in frontline industries, such as health, childcare, and education).24 However, the pandemic has also highlighted the precarious nature of female employment as during the first wave of the pandemic, ‘more working class women than men or women in middle-class jobs saw their already shorter weekly hours cut back’.25 Thus, while it is important to recognise that working-class women will often have a different relationship to production than their male counter-parts, they have traditionally been engaged in one form of production or another and their work has, and continues, to be a vital component of working-class self-making.

Location, Location, Location

Situating the traditional working-class exclusively in ‘left behind’ towns in the North, Midlands, and Wales is also historically inaccurate. Firstly, ‘left behind’ areas also exist in the south. Secondly, doing so ignores the material conditions of the working-class located in the cities, which are traditionally as much a part of the working-class as their counterparts in provincial towns or villages. Hobsbawm notes the centrality of cities to the development of the working-class in the late nineteenth century, as they were the site of ‘the rise of large industrial concentrations where none had existed before’.26 This is not to say that the urban working-class were the sole proprietors of their class’ existence, as Hobsbawm also notes that in the same period of substantial urban growth the number of miners more than doubled. Many of these miners would not have lived in cities but in towns and villages.

However, the ‘traditional’ descriptor acknowledges the significance of towns and villages but ignores the importance of cities. This is despite industry being integral to the growth (and in some cases, existence) of cities across Britain. For instance, Middlesbrough housed industry based on iron and later chemicals, Manchester was a centre of cotton merchanting (and surrounded by a ring of cotton producing towns such as Bolton and Bury), Bradford was built on its wool industry, Sheffield and Merthyr Tydfil were founded on the steel industry, Glasgow became synonymous with shipbuilding, while London’s East End, prior to the expansion of its financial services, was a heartland for manual labour – also centred around shipping.

An important difference between the contemporary working-class and that of the nineteenth century, is that whereas in the nineteenth century many villages, towns, and cities provided opportunities for work (though the work itself was dangerous and physically exhausting), now it is predominantly cities that house new job-creating industries. As capitalism has developed so too have the types of jobs available to working-class people: delivery work, call centres, and fast food have all become typical working-class jobs. Although these jobs will be substantially different from those available to the working-class in the nineteenth century, the conditions of employment are increasingly similar as a result of the growth of the gig economy and erosion of organised labour.27

However, a key difference is that much of this labour, particularly that which is contracted and administered via online platforms, is fragmented. This is helping to create a more atomised working-class, whose work is less social. The consequence of less social processes of production is that this class may find it harder to exercise its power as a collective because the process of ‘socialisation’, that Marx described as an integral part of capitalism and vital to class organising, are absent or minimal.28 In this sense contemporary labour strongly contrasts with the collective industrial processes of the nineteenth century. Although this is not true for all the working-class jobs provided by the modern economy, it is potentially significant for the future of this class.29 The deciding factor as to whether there are different relationships between workers will be the extent to which workers exercise their agency and organise themselves. Only time will tell whether workers will form new social relations with each other and create a collective identity in spite of, indeed in opposition to, the nature of their work. This will be one of the key determinants of the working-class’ future in the twenty-first century.

Regardless of the future alienating and de-socialising effects of working-class work what is evident is that cities are the centre of most working-class people’s relations to production and consumption. Perhaps it is this that is the problem, and why the term TWC strikes such a chord in the ‘left behind’ towns. It is these places that are characterised by the forced deindustrialisation of the mining and manufacturing sector. Consequently, they have undergone significant demographic changes in the last thirty years, not least in youth emigration, which also indicates that the experiences of class will vary considerably depending on age.30 In contrast to cities, these towns are not occupied by multigenerational working-class communities, but by their ghosts. They are places where, borrowing once more from Marx, the memory of life prior to de-industrialisation and the ‘tradition’ of dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living as a misremembered past.

The collective sense of longing is even more important when it is considered what many of these towns have now become. They have not become centres of the lumpen proletariat. Instead, capitalism has filled the vacuum and made use of the surplus labour power.31 The larger mining towns (not the pit villages) and ex-industrial centres now house many new industries, for instances delivery work, warehouses, and call centres.32 As noted above, this work is not as innately social as the ‘traditional’ work of mining and the factory production line, and does not give the town the same sense of identity and community. Thus, the current state of working-class existence in former industrial/mining communities is not part of a tradition. It is a consequence of the death of tradition. The class was permanently estranged from the work that defined it.

One hundred percent Anglo-Saxon, with perhaps just a dash of Viking

Just as women are ignored, and the experience of the urban working-class marginalised, so too is the role of racialised immigrants in shaping working-class history. While the issue of race and racialisation is inexorably tied to migration, it is not only relevant to migration and is not unique to the history of the working-class. The aim of this section is primarily to focus on the impact of migration as the arrival of additional, often racialised, labour that has, through its own organisation and self-making, been integral to the development of the English working-class. The English working-class has never been completely British and has always benefited from substantial immigration. Satnam Virdee points out that the ‘English working class in particular was a heterogeneous, multi-ethnic formation from the moment of its inception’.33 However, many common formulations of the TWC present it as not just white, but as something distinctly British, the understanding of which seems to be based on a historically grotesque conception of the Anglo-Saxon.

The integration of immigrants into the working-class, and society, has never been seamless and they have often been faced with racialised discrimination by local communities and the state. The struggles of this racialised labour has defined the contours of the working-class in the face of oppression from society and the state. A reality once more underscored by the recent expulsion of members of the Windrush Generation in 2018.

The struggle of minorities to be granted the same rights as part of British society and the English working-class, is one of the fundamental processes of the dialectic of working-class self-making. For, on one side, there are groups and forces that attempt to force migrant workers out of the working-class or the labour movement, on the other side there are the migrant workers who, with help from supporters and capitalism’s need for labour power, fight to root themselves in the English working-class. Virdee argues that it was precisely because of their status as racialised outsiders, and their need to assert collective action, that migrants, ranging from Irish Catholics in the nineteenth century to Asian immigrants in the late twentieth century, were able to effect significant changes in the condition of the working-class.

An example of this is the process, set-out by Virdee, in which he details how black members of the working-class, and their struggles, became an important part of the considerations of organised labour in the nineteen seventies and resulted in the articulation of a distinct anti-racist class consciousness in many of the industrial disputes of that decade.34 Although I think that Virdee’s presentation of industrial disputes is too schematic, and the apparent ideological left wing surge in organised labour is overstated, he irrefutably demonstrates that the agency of racialised labour, and its relations to the wider labour movement, are intrinsic components of the self-making of the English working-class.

Racialised immigrant labour influencing the lives of the wider working-class is also evident at the start of this class’ existence. When the working-class came into existence in the nineteenth century much of this immigration was Irish, to the extent that Thompson describes Irish immigration as integral to the making of the English-Working Class.35 Virdee, demonstrates how the Catholic Irish were quickly racialised. This occurred not just in the nineteenth century but also in the twentieth during the inter-war period.36 Despite being racialised and discriminated against, Irish Catholics were fundamental in negotiating with the Admiralty for improvements in pay and conditions and heavily involved in the corresponding societies which provided ‘artisans, shopkeepers, mechanics and general labourers’ – the heroes of Thompson’s incipient working-class – with substantial support.

One of the main charges brought against immigrant labour, and one that fuels its racialisation, is that it is unskilled and drives down the price of indigenous labour, therefore acting as a reserve army of labour and impoverishing the class as a whole. This is often said to have had a particular grievous impact on the TWC.37 This claim is spurious. Thompson notes that in the nineteenth century Irish labour was not particularly cheaper than its English counterpart.38 In fact the Irish often functioned as the ‘unskilled’ labour compared to the ‘skilled’ labour of their English counterparts, in this sense the presence of the Irish may actually have increased the price of English labour, and at the very least allowed English labour to take on what were often more favourable jobs.39 Equally, the substantial immigration from Europe and former British colonies in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War would not have driven down wages overall because there was an acute labour shortage, and the British state was actively recruiting immigrant labour. What is more likely to have happened is that non-white labour will have been artificially devalued. Furthermore, the immigration that was a result of Britain’s membership of the European Union is equally unlikely to have depressed incomes.40

The tensions and racialisation that arise over immigrant labour demonstrate how a class is never completely homogenous and the experiences of its members will vary. However, migrant labour is undisputable part of the English working-class. While some of its experiences will be distinct from other fractions within this class, in practice it does not exist as an isolated group and labours within the same relationships of production. The work performed by the English working-class has depended on the work of immigrants. Any actual traditional working-class must not only take account of the existence of immigration but also of the efforts and struggles of these immigrants to establish their legitimacy and right to exist and work in British society.

Women, immigrants, and the urban working-class chart a course through the history of the English working-class and their tradition of workers’ organisation, as an expression of a class moving from – in the words of Marx – a class in itself to a class for itself.

Conclusion

The above analysis has attempted to provide a brief, and by no means conclusive, sketch of the historic aspects of the self-formation of a multi-faceted class. There are many people who will feel a genuine connection to the conception of the TWC. However, I think that were this term applied with greater historical accuracy rather more people would feel represented by it. Working-class history has affected, and been affected by, women, immigrants, and members of the urban working-class, just as much as any other members of this class. It is important to recognise these traditions, and the various relationships that they entail. Equally, it should be recognised that the rhetorical potency of the term TWC exists precisely because so many working-class traditions have been lost or removed from history. It is an expression of a sensation of loss and awareness of declining material conditions. While the term is often a misremembering of the past it needs to be understood that this misremembering has precisely been enabled by the silencing of historical actors and the destruction of working-class institutions to the extent that large segments of the working-class have been alienated from their own history.

Only by recognising and celebrating these elided historical experiences can any accurate notion of tradition begin to be constructed. This is of paramount importance. If the working-class is to thrive and reverse the decline of its material conditions, then an accurate version of its history needs to be formulated and understood. The past, or rather how people interpret and understand the past, is a powerful source of inspiration and motor for change. In order to affect the right sort of change, and one that is beneficial to this class, it is vital to ensure that an accurate rendition of the past is celebrated.

I have not included any significant analyses of working-class organisations and movements, for instance the trade union and co-operative movements, because the focus of this article was intended to be the categories of individuals, not institutions, that the TWC excludes. As it happens, I do think that the TWC excludes working-class organisations and their integral impact on working-class history. For instance, successes such as the Mechanics’ Institutes of the nineteenth century, the establishment of Ruskin and Plater, and the original iteration of History Workshop are too often forgotten despite them being evidence of the working-class’ capacity for educational self-improvement.

Equally, the fundamental impact that the trade union movement has had on the relations of production cannot be understated. Achievements of sick pay, the eight-hour day, the weekend, paid holiday and parental leave, the minimum wage, protection from discrimination, and equal pay have fundamentally transformed many workers’ relationship with capital. Furthermore, the creation of the Labour Party, born out of the Labour Representation Committee, as a direct product of the trade union movement has also fundamentally shaped the course of British history. While the Labour Party, much like organised labour, cannot claim to have found universal acclaim with the English working-class, the impact its presence has had on this group is as undeniable as is the fact that it would not exist without organised labour. All the above institutions are part of a working-class tradition of establishing movements and organisations for the sake of class advancement and enrichment, but they are seldom incorporated into the popular understanding of working-class tradition.

Just as it is obligatory to investigate the notion of tradition and identify what it includes and excludes, it is just as necessary to recognise what has genuinely changed. For instance, the demographic changes in many of Britain’s communities, the new industries provided by contemporary capitalism, and the declining conditions of employment. These changes lend credence to the superficial construction of the TWC. Classes are in flux and constantly subjected to processes of making and un-making.41 As it stands, the conception of ‘tradition’ does not tell us anything about this class’ relationship to production or other classes, nor does it provide genuine insights into the relationships that constitute the inner-workings of this class. Whereas if we focus on what it omits, we can see that women and immigrants typically experience different relations to production and other members of this class, the same is true of the working-class who reside in cities and are exposed to the latest of capitalism’s machinations.

Meanwhile, the decline of organised labour means that the working-class is now in a more exploitative relationship with capital. Without these qualifications the TWC is a hollow shell of a concept, which does not allow us to compare an accurate construction of the past with the present. The TWC is what Benedict Anderson described as an imagined community. It is a relatively recent invention that makes claims to historical heritage, and its rhetorical potency severely contrasts its intellectual poverty.42

Image "Working Class Hero (Revisited)" byFouquier ॐ is licensed underCC BY-NC-ND 2.0

References

Adler, Paul 2007, ‘Marx, Socialisation and Labour Process Theory: A Rejoinder’, in Organisation Studies, Volume: 28, Issue:9, pp.1387-1394

Anderson, Benedict 2006, Imagined Communities, (London: Verso)

Beatty, Christina, Gore, Anthony, and Forhergill, Stephen, The state of the coalfields 2019: Economic and social conditions in the former coalfields of England, Scotland and Wales, pp.21-25, available at: https://shura.shu.ac.uk/25272/1/state-of-the-coalfields-2019.pdf

Berry, Craig 2017, The proletariat problem: general election 2017 and the class politics of Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn, available at:http://speri.dept.shef.ac.uk/2017/07/05/the-proletariat-problem-general-election-2017-and-the-class-politics-of-theresa-may-and-jeremy-corbyn/

Bottomore, Tom, Laurence Harris, Miliband, Ralph, and Miliband Kiernan, V.G.1994, A Dictionary of Marxist Thought, Oxford: Blackwell.

Eidlin, Barry 2020, ‘Why Union are Good- But Not Good Enough’, Jacobin, available at:https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/01/marxism-trade-unions-socialism-revolutionary-organizing,

Elledge, Jonn, ‘How demographics explains why northern seats are turning Tory’, available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/staggers/2019/12/how-demographics-explains-why-northern-seats-are-turning-tory

Embry, Paul 2019, ‘Why does the Left sneer at the traditional working class?’ UnHerd, available at:https://unherd.com/2019/04/why-does-the-left-sneer-at-the-traditional-working-class/

Federici, Silvia, ‘Social reproduction theory: History, issues and present challenges’, Radical Philosophy 2.04, (Spring 2019), pp. 55-57.

Ford, Robert, and Goodwin, Matthew 2016, Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin, ‘Different Class? UKIP’s Social Base and Political Impact: A Reply to Evans and Mellon’, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 69, Issue 2, April 2016, pp. 480–491.

Greeson, Matthew 2012, ‘Thatcher and the British Election of 1979: Taxes, Nationalization and Unions Run Amok’, Colgate Academic Review, Volume 4, Article 3, pp. 4-12

Hobsbawm, Eric, ‘The Labour Aristocracy in Nineteenth-century Britain’, in Labouring Men: Studies in the History of Labour, (London: Weidenfeld, 1964)

Hobsbawm, Eric 1983, ‘Inventing Traditions’, in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (eds)The Invention of Tradition, pp.1-15, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hobsbawm, Eric 1984, Worlds of Labour, London: George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Limited.

Hoggart, Richard 1957, The Uses of Literacy, London: Chatto and Windus.

Jones, Owen 2016, There’s a fight over working-class voters. Labour must not lose it, available at:https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/oct/06/fight-working-class-voters-labour

Lyonette, Clare and Warren, Tracey 2020, Are we all in this together? Working class women are carrying the work burden of the pandemic, available at:https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/covid19/2020/11/12/are-we-all-in-this-together-working-class-women-are-carrying-the-work-burden-of-the-pandemic/

Thoburn, Nicholas, ‘Difference in Marx: the lumpenproletariat and the proletarian unnamable’ Economy andSociety Volume 31 Number 3 August 2002: 434–460, pp. 443-444

Marx, Karl 1992, Capital Volume Three, London: Penguin.

McIlroy, John 2014, ‘Marxism and the Trade Unions: The Bureaucracy versus the Rank-and-File Debate Revisited’, Critique, 42:4, pp. 497-526.

Mezzadri, Alessandra, ‘On the value of social reproduction: Informal labour, the majority world and the need for inclusive theories and politics’, Radical Philosophy 2.04, (Spring 2019), pp.33-41

Murray, Toney 2016, No reason to doubt No Irish, no blacks signs, The Guardian: available athttps://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/28/no-reason-to-doubt-no-irish-no-blacks-signs

Moss, Jonathan 2019, Women, workplace protest and political identity in England, 1968-85, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Mulholland, Marc 2009, Marx, the Proletariat, and the “Will to Socialism”’, in Critique, 37:3, pp. 319-341.

O’Connor, Sarah, ‘ “Lazy” Britons aren’t the reason for the UK migrant workforce’, Financial Times, available at:https://www.ft.com/content/eb5e3bd7-c8bf-4934-b60e-0e49152183a5

Partington, Richard 2019, ‘Gig economy in Britain doubles, accounting for 4.7 million workers’,The Guardian, available at:https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jun/28/gig-economy-in-britain-doubles-accounting-for-47-million-workers

Price, Richard, ‘Review: the Segmentation of Work and the Labour Aristocracy’, Labour / Le Travail

Vol. 17 (Spring, 1986), pp. 267-272

Savage, Mike, et al. 2013, ‘A New Model of Social Class? Findings from the BBC’s Great British Class Survey Experiment’, Sociology, 47(2), 2013, pp. 219-250.

Schwartz, Laura, 2019, Karl Marx and Domestic Servants: A historical overview of Marx's and Marxist thinking on domestic workers, reproductive labour and class struggle, available at:https://www.academia.edu/42641042/Karl_Marx_and_Domestic_Servants_A_historical_overview_of_Marxs_and_Marxist_thinking_on_domestic_workers_reproductive_labour_and_class_struggle

Smith, Dave 2020, ‘Cheap migrant labour is a myth and so is its effect on productivity’, The Times, available at:https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/cheap-migrant-labour-is-a-myth-and-so-is-its-effect-on-productivity-hv3s8vt8x

Thompson, Edward 1964, The Making of the English Working Class, New York: Pantheon Books.

Thorpe, Keir 2000, 'Rendering the Strike Innocuous': The British Government's Response to Industrial Disputes in Essential Industries, 1953-55’, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Oct. 2000), pp.577-600.

Toscano, Alberto and Woodcock, Jamie 2015, “Spectres of Marxism: A Comment on Mike Savage’s Market Model of Class Difference”, The Sociological Review, 2015, available at:https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1111/1467-954X.12295

Unknown 2019, Trade Union Membership, UK 1995-2019: Statistical Bulletin, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/887740/Trade-union-membership-2019-statistical-bulletin.pdf

Virdee, Satnam, ‘A Marxist Critique of Black Radical Theories of Trade-union Racism’, Sociology, August 2000, Vol. 34, No. 3 (August 2000), pp. 545-565

Virdee, Satnam, Racism, Class and the Racialized Outsider, (London: Red Globe Press, 2014)

Vogel, Lise, Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory, (Boston: Leiden, 2013)

Walker, Martin 2012, “The Origins and Development of the Mechanics’ Institute Movement 1824 – 1890 and the Beginnings of Further Education”, Teaching in Lifelong Learning 4(1), available at: https://www.teachinginlifelonglearning.org.uk/article/id/136/

Wilson, Dolly 2006, ‘A New Look at the Affluent Worker: The Good Working Mother in Post-War Britain’, Twentieth Century British History, 2006, vol.17(2), pp.206-229.

- 1. Some of the examples of the term from across the political spectrum are: Labour is no Longer the party of the traditional working-class, available at: https://www.economist.com/bagehots-notebook/2018/07/06/labour-is-no-longer-the-party-of-the-traditional-working-class (accessed 15.01.2021) To win back the working class we must ditch identity politics, available at: https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/f/win-back-working-class-we-must-ditch-identity-politics (accessed 15.01.2021) Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin, ‘Different Class? UKIP’s Social Base and Political Impact: A Reply to Evans and Mellon’, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 69, Issue 2, April 2016, pp. 480–491. Owen Jones, There’s a fight over working-class voters. Labour must not lose it, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/oct/06/fight-working-class-voters-labour (accessed 15.01.2021) Craig Berry, The proletariat problem: general election 2017 and the class politics of Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn, available at: http://speri.dept.shef.ac.uk/2017/07/05/the-proletariat-problem-general-election-2017-and-the-class-politics-of-theresa-may-and-jeremy-corbyn/ (accessed 15.01.2021).

- 2. Although the trials and tribulations of the British Labour Party do not have a monopoly on class discourse in the UK they still have a considerable effect its contours.

- 3. Paul Embry, ‘Why does the Left sneer at the traditional working class?’ UnHerd, available at: https://unherd.com/2019/04/why-does-the-left-sneer-at-the-traditional-working-class/, (accessed, 21.02.2021). I disagree with much of Embry’s construction of class here, but he deserves acknowledgement for putting more thought into the term ‘traditional working-class’ than most.

- 4. Mike Savage, Fiona Devine, Niall Cunningham, Mark Taylor, Yaojun Li, Johs. Hjellbrekke, Brigitte Le Roux, Sam Friedman, and Andrew Miles, ‘A New Model of Social Class? Findings from the BBC’s Great British Class Survey Experiment’, Sociology, 47(2), 2013, pp. 219-250, p.240.

- 5. Eric Hobsbawm, ‘Inventing Traditions’, in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (eds) The Invention of Tradition, pp.1-15, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), p.1.

- 6. Ibid, p.10.

- 7. Satnam Virdee, ‘A Marxist Critique of Black Radical Theories of Trade-union Racism’, Sociology, August 2000, Vol. 34, No. 3 (August 2000), pp. 545-565, p.560.

- 8. Marc Mulholland, Marx, the Proletariat, and the “Will to Socialism”’, in Critique, 37:3, pp. 319-341. Michael Simpkins’ What’s My Motivation? provides an insight into the life of an actor in a precarious labour market selling their labour power for very little.

- 9. Eric Hobsbawm, ‘The Labour Aristocracy in Nineteenth-century Britain’, in Labouring Men: Studies in the History of Labour, (London: Weidenfeld, 1964), p. 272.

- 10. Tom Bottomore, Laurence Harris, V.G. Kiernan, and Ralph Miliband (eds.), A Dictionary of Marxist Thought, (Oxford: Blackwell 1994), p. 296.

- 11. Richard Price, ‘Review: the Segmentation of Work and the Labour Aristocracy’, Labour / Le Travail Vol. 17 (Spring, 1986), pp. 267-272.

- 12. E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Pantheon Books, 1964) p.9.

- 13. A demonstration of the difficulties with identifying class membership detached from productive forces is the Guardian’s North of England Editor claiming an artisanal pizza shop owner and retired nurse unquestionably part of the same class: available at https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jul/08/imagine-the-state-wed-be-in-if-corbyn-had-been-in-charge-the-view-from-the-red-wall (accessed 15.01.2020)

- 14. Richard Hoggart, The Uses of Literacy (London: Chatto and Windus, 1957) p.16. One of the main flaws with Hoggart’s presentation of the working-class family is that it is built on the assumption of marriage; that it does not account for single parent families, even though they are an equally legitimate form of family.

- 15. Lise Vogel, Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory, (Boston: Leiden, 2013), pp. 152-154, Alessandra Mezzadri, ‘On the value of social reproduction: Informal labour, the majority world and the need for inclusive theories and politics’, Radical Philosophy 2.04, (Spring 2019), pp.33-41, and, Silvia Federici, ‘Social reproduction theory: History, issues and present challenges’, Radical Philosophy 2.04, (Spring 2019), pp. 55-57.

- 16. While the debate around whether social reproduction is productive or unproductive labour is interesting from a theoretical standpoint, I think that it does not particularly matter. The fundamental conditioning factor of the relationships that create the material reality of social reproduction is that the labour itself is unpaid and built on institutionalised social norms and is these factors that have resulted in it not being regarded as proper work and not adequately compensated/supported by the state/employers.

- 17. While the debate around whether social reproduction is productive or unproductive labour is interesting from a theoretical standpoint, I think that it does not particularly matter. The fundamental conditioning factor of the relationships that create the material reality of social reproduction is that the labour itself is unpaid and built on institutionalised social norms and is these factors that have resulted in it not being regarded as proper work and not adequately compensated/supported by the state/employers.

- 18. Ibid, p.1.

- 19. Dolly Wilson, ‘A New Look at the Affluent Worker: The Good Working Mother in Post-War Britain’, Twentieth Century British History, 2006, vol.17(2), pp.206-229, p.222.

- 20. Ibid.

- 21. Jonathan Moss, Women, workplace protest and political identity in England, 1968-85 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), p.165.

- 22. Ibid, p.164.

- 23. Trade Union Membership, UK 1995-2019: Statistical Bulletin, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/887740/Trade-union-membership-2019-statistical-bulletin.pdf (accessed 16.01.2021). This report states that women account for 3.9 million of British trade unionism’s 6.44 million members. (3.9/6.44)*100 = 57.

- 24. Clare Lyonette, and Tracey Warren, Are we all in this together? Working class women are carrying the work burden of the pandemic, available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/covid19/2020/11/12/are-we-all-in-this-together-working-class-women-are-carrying-the-work-burden-of-the-pandemic/

- 25. Ibid.

- 26. Eric Hobsbawm, Worlds of Labour, (London: George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Limited 1984), p.197.

- 27. Richard Partington, ‘Gig economy in Britain doubles, accounting for 4.7 million workers’, The Guardian, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jun/28/gig-economy-in-britain-doubles-accounting-for-47-million-workers (accessed 17.01.2021).

- 28. Paul Adler, ‘Marx, Socialisation and Labour Process Theory: A Rejoinder’, in Organisation Studies, Volume: 28, Issue:9, pp.1387-1394, p.1387.

- 29. Industries such as fast food are still part of a socialised labour process. A good example of this is McStrike. On 18 November 2019 McDonalds workers in South London commenced industrial action the latest in a series of global industrial action by fast food workers. The main demands of the strike were pay rise to £15 an hour and secure terms of employment in the form of a forty-hour week. A significant enable of this labour militancy was that the relevant workplaces were located relatively close together and that the labour itself was still a collective process.

- 30. Jonn Elledge, ‘How demographics explains why northern seats are turning Tory’, available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/staggers/2019/12/how-demographics-explains-why-northern-seats-are-turning-tory (accessed: 18.01.2021). Young people having to leave home and travel to the city looking for work is in fact one of the great traditions of working-class existence as economic necessity drives internal migration.

- 31. By lumpenproletariat I mean a group of people who exist outside typical relations of production, as is detailed here: Nicholas Thoburn, ‘Difference in Marx: the lumpenproletariat and the proletarian unnamable’ Economy and Society Volume 31 Number 3 August 2002: 434–460, pp. 443-444.

- 32. Christina Beatty, Stephen Forhergill, and Anthony Gore, The state of the coalfields 2019: Economic and social conditions in the former coalfields of England, Scotland and Wales, pp.21-25, available at: https://shura.shu.ac.uk/25272/1/state-of-the-coalfields-2019.pdf, (accessed: 09.02.2021)

- 33. Satnam Virdee, Racism, Class and the Racialized Outsider, (London: Red Globe Press, 2014) p. 162.

- 34. Satnam Virdee, ‘A Marxist Critique of Black Radical Theories of Trade-union Racism’, Sociology, August 2000, Vol. 34, No. 3 (August 2000),

- 35. The Making of the English Working Class, pp.429-437.

- 36. Racism, Class and The Racialized Outsider, pp.14-17, and Tony Murray, ‘No reason to doubt No Irish, no blacks signs’, The Guardian: available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/28/no-reason-to-doubt-no-irish-no-blacks-signs (accessed 18.01.2021).

- 37. I think that quite often distinctions of skilled vs unskilled (particularly now when skill is normally qualified by a level of qualification) are misleading and often a means of trying to control the supply and direction of labour, this also complicates the applicability of the Labour Theory of Value. A more useful way of deciding the value of labour would perhaps be to examine the use value of the products of specific labour power, though this would of course be subjective. The Making of the English Working Class, pp.433.

- 38. The Making of the English Working Class, pp.433.

- 39. A modern equivalent of this can be found in the predominantly immigrant labour that works as picking jobs in the UK’s farmer’s industry. For most indigenous workers, working as a food picker does not offer better pay to working in a supermarket or café, though for many migrant workers it offers better pay than many of the jobs in their previous country. Thus, the job of food picking is done by a majority migrant workforce, enabling the indigenous labour to seek marginally better/more enjoyable jobs, and that food prices can stay relatively low. Sarah O’Connor ‘“Lazy” Britons aren’t the reason for the UK migrant workforce’, Financial Times, available at: https://www.ft.com/content/eb5e3bd7-c8bf-4934-b60e-0e49152183a5 (accessed 11.02.2021).

- 40. Dave Smith, ‘Cheap migrant labour is a myth and so is its effect on productivity’, The Times, available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/cheap-migrant-labour-is-a-myth-and-so-is-its-effect-on-productivity-hv3s8vt8x (accessed 18.01.2021).

- 41. Alberto Toscano and Jamie Woodcock, “Spectres of Marxism: A Comment on Mike Savage’s Market Model of Class Difference”, The Sociological Review, 2015, available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1111/1467-954X.12295, (accessed 19.01.2020).

- 42. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, (London: Verso 2006), p.5.

On Violence: A Reply to Ugo Palheta’s ‘Fascism, Fascisation, Antifascism’

David Renton

Thanks are owed to Historical Materialism for publishing Palheta’s piece, which is wide-ranging and compelling.1 I have learned from it, and I am sure other readers feel the same. His article begins from an instinct that we have to explain the crisis of the present, rather than merely repeat models developed from the past. Like him, I despair of the tendency of the left to assume that, because some writer in the distant past said that fascism must take certain forms, so it is necessary to read those forms into the present, even where they do not exist. In what follows, I will take issue with one part of Palheta’s argument in particular, his fifteenth thesis – on violence. My criticisms are narrow and formulated in a spirit of gratitude to him for his contribution.

“It is undeniable,” writes Palheta, “that extra-state violence, in the form of mass paramilitary organisations, has played an important (though probably overestimated) role in the rise of fascists.” It seems to me that, from this point onwards, there are two processes of historical revision in his work. First, Palheta reduces the utility of violence to fascism, seeing it as something which contributed only prior to the fascist take-over of power. There is no reason to make that assumption. If other writers were to follow him, we would miss what most contemporaries saw as the distinctive acts of fascism: the willingness of states to employ violence (war) against the other states around them, and to carry out racial genocide in Europe. “Other reactionary movements” have employed violence, Palheta states. This is true, but only to an extent. Since 1918, however, Italy and Germany are the only countries from what we used to call the First World to have employed war against other states, or genocide against citizens, in the global core.2

Second, Palheta raises the possibility of a fascism without armed bands, or without violence at all. “But neither the constitution of armed bands, nor even the use of political violence, is the hallmark of fascism, either as a movement or as a regime.” If it is possible to imagine a successor to Hitler or Mussolini without violence, and who will not reduce Europe or the world to genocide or war, then in what meaningful sense would that successor still be fascist? If they were going to be a fascism not in discontinuity with ordinary centre-right government3 but in continuity with it, then why have anti-fascism? For, 70 years of political campaigning has been premised on the assumption that fascism marked a change from normal politics to something worse.

The most sophisticated attempt to explain how fascism operated, as a series of political strategies employing violence in different ways as fascism evolved, belongs to the historian of French fascism Robert Paxton and his model of the five stages of fascism.4 In their initial stage, fascists won recruits through mass demonstrations, through military training and attacks on their opponents. In the second stage, when fascist parties were contending for power, they needed to challenge the state’s monopoly of violence. Yet fascism, at this stage, also typically sought to govern in an alliance with other right-wing parties, hence there was a tension between the interests of the party and of its militia. On taking power, both fascist parties partially relegated their militia structures and promised to rely on the existing structures of the state to punish any remaining left-wing opponents. As fascism became more radical in office, a much more ambitious kind of violence became available to it: the use of military power in war, to create new forms of colonial rule, and to enact genocide against fascism’s racial enemies. In this model, which applies just as well to both Italy and Germany, as well as to the fascist parties which never captured power, fascism is distinguished by violence and it is recurring, however the form in which violence is expressed in changes in fascist tactics at each stage.

There is a reason why Paxton’s model of fascism has been cited from liberals through to Marxists and by everyone in between. It makes sense of the very high levels of political violence in Italy prior to Mussolini’s seizure of power, the use of torture and murder in the consolidation of that regime (the murder of Matteotti), etc. Compared to it, Palheta’s insistence that “The most visible dimension of classical fascism, its extra-state militias, are, in fact, an element subordinate to the strategy of the fascist leaderships, who use them tactically,” is much thinner. Yes, of course, the fascist militia were used selectively: the political leaders would on occasion distance themselves from them.5 After all, there was more than one potential source of violence available to them. Ultimately, the German and Italian armies were a greater prize to Hitler or Mussolini than the fascist bands. But that it no way invalidates the general point that fascism without political violence is like Marxism without the working class.

Palheta notes that neo-fascist parties (including the Rassemblement National), have given up the aspiration to build a militia. He gives five reasons for that process. He knows the politics of the RN far better than I do and from this distance, his explanations seem compelling. He is certainly correct, for example, to refer to a long historical process of the delegitimisation of political violence, which is both a product of the fascist experience, and was a major obstacle to an earlier generation post-war fascist parties (such as the National Front in Britain) who rapidly lost popularity after they became publicly associated with street violence.6

What he does not go on to ask is whether that choice, the deliberate disavowal of the possibility of violence, or its concomitants (a willingness to accept ordinary electoral conflict as the sole legitimate terrain of political competition), have any effect on the neo-fascist party. For, once a tradition steeped in violence and the rejection of ordinary politics, gives up the possibility of taking power through a coup and insists on its “normality”, the customary path is for that politics to become more moderate and ultimately indistinguishable from the parties around it.

This was a question I posed in my book The New Authoritarians.7 In the past century, there were repeated examples of parties which had at one time challenged the state monopoly of violence, only to relinquish that challenge. Such parties have tended to become more moderate over time. Those parties have been seen on both the left (the Communists) and the right (the Italian MSI/AN). Are there reasons to expect that the Rassemblement National will follow a different trajectory in power?

This question is a difficult one. I can think of affirmative answers relating not so much to the RN specifically, but to the period we are in, and the part played within the far right by fascism, which causes such politics to recur.8 No doubt, other writers can come up with better answers, more rooted in the history of that particular formation. But the question cannot be evaded by writing about Mussolini or Hitler in a way which makes their politics unrecognisable.

Palheta’s writing is shaped not merely by the experience of the RN in opposition, but also of Emmanuel Macron in power. His category of “neo-fascism” is broad enough to take in both “fascism” (the RN as an outsider party) and “fascisation” (En Marche in office). It seems to me that there are other political theories which might make just as well explain the latter: a form of leadership which charges itself as an emergency regime necessary to prevent what would otherwise be the rise of fascism, and uses the threat of the far right to justify its own form of authoritarian rule has a very obvious counterpart in history, not in fascisation (i.e. Third Period Comintern fantasies about the authoritarianism concealed in liberalism and social democracy),9 but in the failed “preventative” dictatorships of Papen and von Schleicher in Germany.10

While we are in a period advantageous to many different styles of politics which are comfortable with forms of semi-authoritarian rule, the balance of forces varies from country to country. The example of France is relatively untypical, in at least three ways: in the political hegemony of a party of fascist origin on the right; in the irreconcilability of that party to any offer of coalition with a more moderate partner, and in the measures adopted by the political system to find an alternative to what otherwise seems inevitable government by that party.

By contrast, in Britain, a more militant right-wing politics has grown by capturing the main right-wing party, or in America, a Republican President reached the limits of what was possible without summoning an army of his supporters into the street. The deaths in the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 show that, as distant as political violence has seemed for most of the past four years, in circumstances of authoritarian advance that option can return.11

In conclusion, I agree with Palheta in his project of treating the authoritarian politics of the present as a coherent whole. I think, most importantly, that he is right to urge anti-fascists to turn their attention from the street groups to the people holding power. But, if the word “neofascism” is to have real meaning – then that is itself a warning that France may well be set on a path of mass suffering, from which she can only be saved by concerted political action. If that prediction is true, then all of us need to develop a more sophisticated explanation of how the seeming absence of violence in the present forms the mere prelude to its ubiquity in the near future.

- 1. https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/blog/fascism-fascisation-antifascism

- 2. Palheta’s seventeenth thesis rightly addresses the relationship between fascism and the legacy of colonialism.

- 3. Plainly, ordinary capitalist government of the centre-right or centre-left already assumes a degree of violence – in British terms, the attack on the miners, the Falklands war, or the Iraq war. To speak of fascism or even neo-fascism requires more than this.

- 4. R.O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism (London: Penguin, 2004).

- 5. One example of such disassociation, Hitler’s distancing himself from his party’s use of murder in early 1930s Berlin, is at the core of B. C. Hett, Crossing Hitler: The Man Who Put the Nazis on the Witness Stand (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- 6. This is one of the themes of D. Renton, Never Again: Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League 1976-1982 (London: Routledge, 2018).

- 7. London: Pluto, 2019.

- 8. D. Renton, 'Will Fascism Return to the Far Right?', Jacobin, 10 February 2019.

- 9. For this genre and its insistence that even after 1933 social democracy remained Communism’s first antagonist, R. Palme Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution: A Study of the Economics and Politics of the Extreme Stages of Capitalism in Decay (London: Martin Lawrence, 1934), p. 112.

- 10. And behind them, chapter 7 of Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.

- 11. For a case study of radicalisation among Trump’s supporters, C. Sheets, 'The Radicalization of Kevin Greeson,' ProPublica, 15 January 2021.

National Identity and Pre-Capitalist Europe

A Thinker’s Imperative

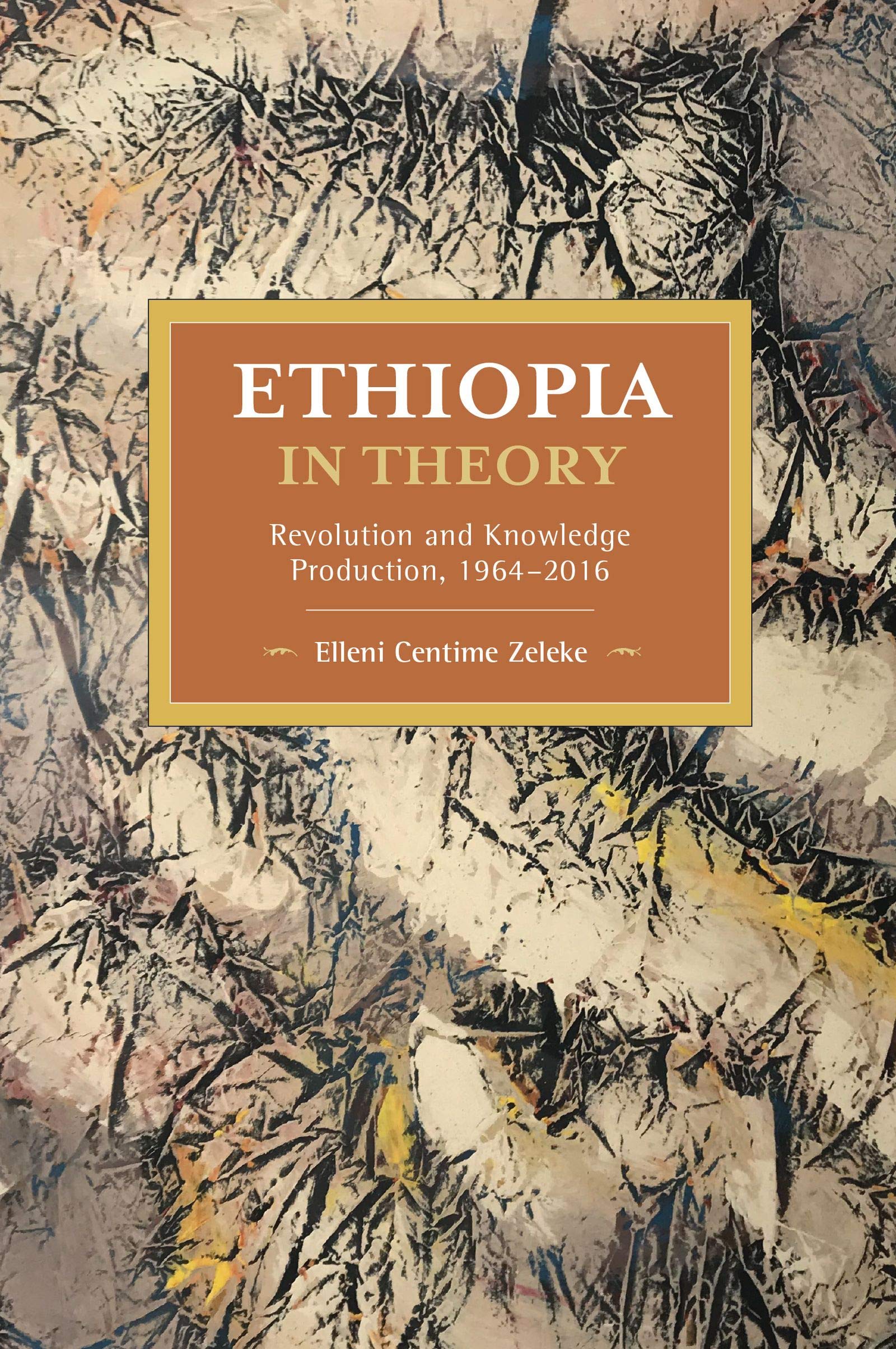

A Review of Ethiopia in Theory: Revolution and Knowledge Production, 1964–2016 by Elleni Centime Zeleke, Haymarket Books 2020

Susan Dianne Brophy

Associate Professor, Department of Sociology & Legal Studies, St Jerome’s University, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

susan.brophy@uwaterloo.ca

Abstract

This review of Ethiopia in Theory retraces author Elleni Centime Zeleke’s dialectical method. Necessary to navigate the full range of what this book offers, it is this approach that allows her to bring the poetic to bear against the programmatic and deliver a transfixing study of knowledge production. Zeleke’s revolutionary critique of revolutionary practice centres Africa as a site of knowledge production, the result of which is a multifaceted account of recent Ethiopian history that offers lessons for all critical thinkers.

Keywords

Ethiopia – state – revolution – knowledge production – social science – immanent critique

Elleni Centime Zeleke, (2020) Ethiopia in Theory: Revolution and Knowledge Production, 1964–2016,Historical Materialism Book Series, Leiden: Brill.

Released under the banner of the Historical Materialism Book Series, Elleni Centime Zeleke’sEthiopia in Theory stakes claims in various streams of Marxist scholarship. While it is the author’s prerogative to let the readers assess for themselves where in Marxist scholarship to situate this book, the signposts are plain to see in its dominant arc and supporting currents. The question then becomes: who is ignoring these signs? I offer this commentary to those who deem the work too niche for their purposes based on the title alone, but who otherwise seek to undertake or understand social change – the presumptive aims of all Marxist scholars. It is precisely because of that impulse to skip the book that you should not: the imperative that Zeleke advances applies most to those who believe themselves least in need of heeding it.

This book displays the best of Marxist scholarship. In the first part of this review, I identify the prevalent Marxist streams and note Zeleke’s contributions to critical areas. In the second part, I deploy a dialectical method that complements Zeleke’s approach, and which allows me to extract the text’s most remarkable elements.

Part I: Situating

The image that first comes to mind in the opening paragraph of Ethiopia in Theory is that of the Angelus Novus, long associated with Walter Benjamin.

Arc

Zeleke’s contribution to Marxist scholarship is a revolutionary critique of revolutionary practice that centres Africa as a site of knowledge production; more precisely, she looks to recent Ethiopian history to draw lessons for all critical thinkers. In the first half of the book, Zeleke studies the writings by leaders of the student movement, gathering evidence of the futility of pursuing revolutionary ends within a social-scientific programme. She is determined to understand the past without letting it dominate the present in the service of an unknowable future, and Benjamin is her reference point for how to approach history without committing the same sins as the student leaders.

In the first chapter she writes: ‘I take seriously Walter Benjamin’s idea that the future is a bit like a medusa – we cannot have an open future if we try to stare into it. It is better to spatialise history: explode the sediments (or here, the tapestry) of the past’ (p. 36). Zeleke elaborates on this in the sixth chapter, explaining how history treated as sediment ripe for purposeful excavation breeds conservatism, evinced by the rush to authenticity as the fount of truthmaking. Be it cultural traditions or revolutionary concepts, Zeleke insists that it is necessary to avoid fixing these abstractions as transhistorical ideals and instead understand ‘their genesis in social practice’ (p. 199). With references to the Frankfurt School throughout this chapter (pp. 188, 199, 249–51), this epistemological turn is anticipated in the subtitle of the book, Revolution and Knowledge Production, which promises a reckoning between the hubris of enlightened rationality and the materially constrained ‘ways of knowing ourselves’ (p. 192). This reckoning takes the form of an immanent critique – which I substantiate in the second part of the review – and shapes her contributions in other currents of Marxist scholarship.

Currents

With Ethiopia in Theory, Zeleke contributes a much-needed update on Marxist approaches to anticolonial studies. Afflicted to varying degrees by a romanticisation of the Non-Aligned Movement and the insidious Eurocentrism of settler-colonial studies, she raises the calibre of scholarship with a sharp historical-materialist eye. Zeleke’s willingness to indulge in the generative force of contradiction allows her to move past simplistic dichotomies such as internal/external, modern/traditional, core/periphery, and scientific/mythological (p. 83), but do so without dissolving the constitutive differences at work. These discreet adjustments are scattered throughout the text, although the best example is her use of the archives.

‘Dealing with African society’s historicity requires more than simply giving an account of what occurred on the continent; it also presupposes a critical delving into western history and the theories that claim to interpret it’ (p. 198). It is in this light that one must interpret both Zeleke’s archival findings and her motivation to undertake archival work in the first instance. More than a repository of artefacts and memories unique to a specific time and place, the journals of the student movement chronicle a dialogue between theory and practice. Provincializing Europe by Dipesh Chakrabarty helps Zeleke explain how the students’ epistemic practices domesticated external influences (p. 203), leaving in their wake journal entries that contain the sediments not only of Ethiopian realities and European ideals, but also of Ethiopian ideals and European realities.

The problematic conflation of ‘anti-colonial answers with post-colonial questions’ (p. 25) is detailed in the first half of the book, where Zeleke studies the archival records to chart the adoption of European conceptions of nation-statehood in the anti-colonial nationalism of the Ethiopian student movement (p. 42). To embrace the nation-state and repurpose it for revolutionary ends, the anti-colonial nationalist exercises a ‘functionalist reading of culture’ (p. 82), a point that Zeleke makes with reference to Partha Chatterjee. With the broader arc of the text in mind, she pushes this assessment further: the students were not merely instrumentalising concepts as an intellectual pose – their adoptive and transformative acts were ‘actually connected to social processes in the world’ (pp. 83–4). Here, Zeleke’s anti-colonial approach shows how ‘becoming’ is variably beset and propelled by the conceptual pillars of developmentalism: state, progress, and modernity.

What is interesting about Zeleke’s contribution on this front is not her exposure of the contingencies of anti-colonial thought, but rather her drive to understand how, why, and to what effect these contingencies are exploited and rationalised. For instance, she notes that in the citizen/urban versus tribal/rural divide that permeates the Ethiopian social, political, and economic landscapes, ‘race is veiled through a discourse of the city as modern or civilised’ (p. 231). The social-scientific rationalisations that simultaneously fetishise Africa (p. 200, n. 42) and champion modernity imbibe these contingencies of anti-colonial thought, which for Zeleke discloses the possibility that ‘state sovereignty is premised on being both anti-colonial and anti-black at the same time’ (p. 231). The terms of knowledge-production thus revealed, Zeleke raises the standards and stakes of studies situated at the crossroads of racism, colonialism, and capitalism, which shapes her contribution to the ‘transition debates’.

For readers puzzled by the complexity of this book’s content, its main point is made obvious in the form. Zeleke centres Africa and the specifics of the Ethiopian student movement as the site of knowledge production and decentres that ‘lively debate’ on the ‘world-historical transition from feudalism to the capitalist mode of production’ (p. 209). Although this book is very much a commentary on transitions to capitalism, anyone exhausted by Eurocentrism might have a fleeting sense of relief upon realising that the name ‘Brenner’ does not appear until page 209.

The arc of the book – emphasising the contingencies of social processes throughout history – leads Zeleke to reject the assumed linearity of the transition to capitalism. Instead, she draws from the debates, specifically from the contributions of Jairus Banaji and Henry Bernstein, an understanding that ‘customary social relations and the commodification of the peasant economy are not intrinsically opposed’, an opening she welcomes because of its potential for renewed inquiry (p. 222). While questioning the historical and explanatory necessity of a transhistorical concept of labour, she ponders whether it is possible to adhere to a vision of social progress while pursuing ‘a non-Eurocentric history of capitalist development’ (p. 243). She tests this hypothesis in her execution of an immanent critique, effectively situating herself, the student revolutionaries, and the tiller within a non-Eurocentric history of capitalism while also articulating a thinker’s imperative: the obligation to progress in the face of failure.

Part II: Moving

Ethiopia in Theory does not dwell for long on the common ground that exists between the author and the subjects of the text (p. 10); Zeleke’s ‘ghosts of the past’ are ‘not the same ones’ (p. 26) as the bygone student-movement leaders turned latter-day academics and politicians (p. 95). How she narrates this tension between familiarity and estrangement seems to anticipate the raw nerves of her readers, who are likely to have varied yet ardent ideas about this recent history. Zeleke’s attentiveness to this possibility may be why she appears willing to undertake this critique on ‘their’ (i.e. students’, academics’, and politicians’) terms, as if to quell the anxiety that inhibits immersion. Uninterested in passing judgement on the quality of the social-scientific outputs of the students and academics (pp. 11, 79, 98), she also agrees to take them at their word when the students claim to be ‘scientists’ (p. 98). Whether this overture is an act of condescension or concession is debatable. Either way, it is a trademark of immanent critique. As the methodological spine that connects what otherwise might be read as disparate theses, Zeleke’s execution of this immanent critique is brilliant – in part because of, not despite, its fallibilities.

The tripartite structure of this portion of the review (Intent, Failure, and Obligation) is inspired by a quote from the end of the book: ‘Obligation for the critical theorist must come from what is immanent to human knowledge – which is a social self that struggles to shape society and as such is aware of the relation between rational intention and its (failed) realisation’ (p. 252). Organised to reflect the progressive logic of dialectical analysis, this is an attempt to follow the signposts that Zeleke provides her readers to assist their interpretation of her work. This structure is also an apt way to draw knowledge from the quote itself, which I return to at the end.

Intent

There is a hint of exasperation throughout Ethiopia in Theory. With her attention to historical detail propelled by a sense that an explanation is overdue, Zeleke records educational trajectories (pp. 100–1) and discloses pen names (see for example: pp. 106, 110, 122, 123), tracking the rising and fading tendencies of the student movement during the last decade of Haile Selassie’s rule and in the midst of a cresting cold war. As she peels back the layers, Zeleke confiscates the reasons that excuse evasiveness among student-movement leaders and academics-turned-politicians, leaving only the demand for an answer to a simple question: What do you have to say for yourself?