MEGA

MEGA in Greece: Reflections on Translating and Editing Marx’s Writings

The reception and dissemination of Karl Marx’s opus in Greece, in its first steps during the interwar period, is combined with the development of the nascent labour movement. Already before WWII, there were more several attempts to translate Das Kapital, whereas many of the minor ‘canonical’ works (Manifesto of the Communist Party, On the Jewish Question, etc.) had been translated and published in the form of brochures (or newspaper articles) for the benefit of the militant classes. The militant aspect of the translations, i.e., their instrumental incorporation into the realm of political praxis in the form of an exemplary discursive reference,[1] was a feature that would accompany the translations of the majority of Marxian works in the following decades.

A French edition of the works of Marx and Engels based on MEGA-2: the GEME project

The aim of this article is to present the main features of the Grande édition Marx et Engels (GEME)[1] project from a specific angle: that of the dissemination, in France and more generally in the French-speaking world, of the philological advances made possible by the second Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA-2).[2] The aim here is not to revisit the general theoretical issues[3] of the GEME project, but, rather, to situate it within the history of Marx and Engels editions in France in order to show the contribution made by the various volumes published since its launch in 2008 and to indicate how future volumes are likely to extend it.

Notes on the Translation of Some Specialist Marxist Terms into Italian and English

Adapted and translated by Gregor Benton and Ingrid Hanon

The Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe in Italy

The second Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe has enjoyed a degree of popularity in Italy since the late 1970s.

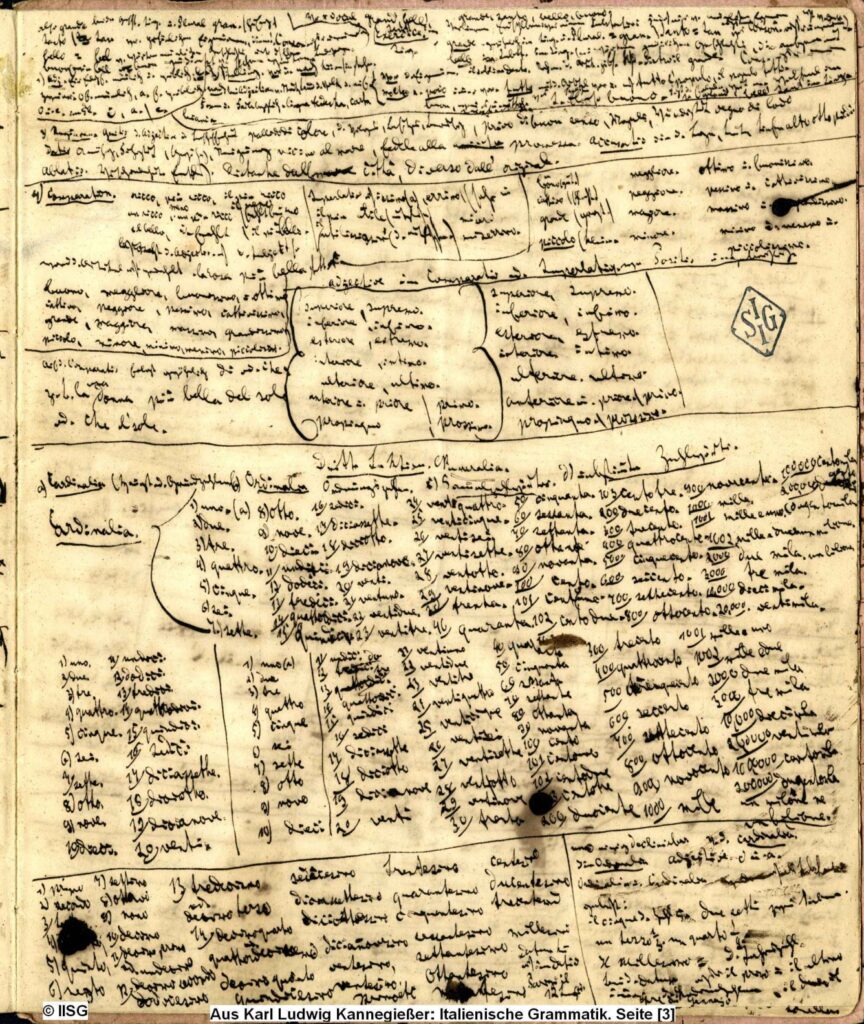

Marx and Engels as Polyglots

Karl Marx’s 1852 work The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte opens with the famous remark that men ‘make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please.’[1] He goes on to argue that whatever happens in the present time arises from and is a reaction to a political past. Recollecting and interpreting the past for present purposes requires a language. Such a language is not naturally given but needs to be socially constructed. What is more, its vocabulary and grammar stem from linguistic legacies of past ideologies. Marx draws in this regard an analogy, comparing acquisition of a political language with mastering a natural language:

MEGA (From the Historical-Critical Dictionary of Marxism)

Translation of the entry ‘MEGA’ in the Historical-Critical Dictionary of Marxism (Historisch-Kritisches Wörterbuch des Marxismus [HKWM]), vol. 9/I (Hamburg: Argument, 2018), pp. 388-404. Part I written by Rolf Hecker, Manfred Neuhaus, Richard Sperl, and part II by Hu Xiaochen.