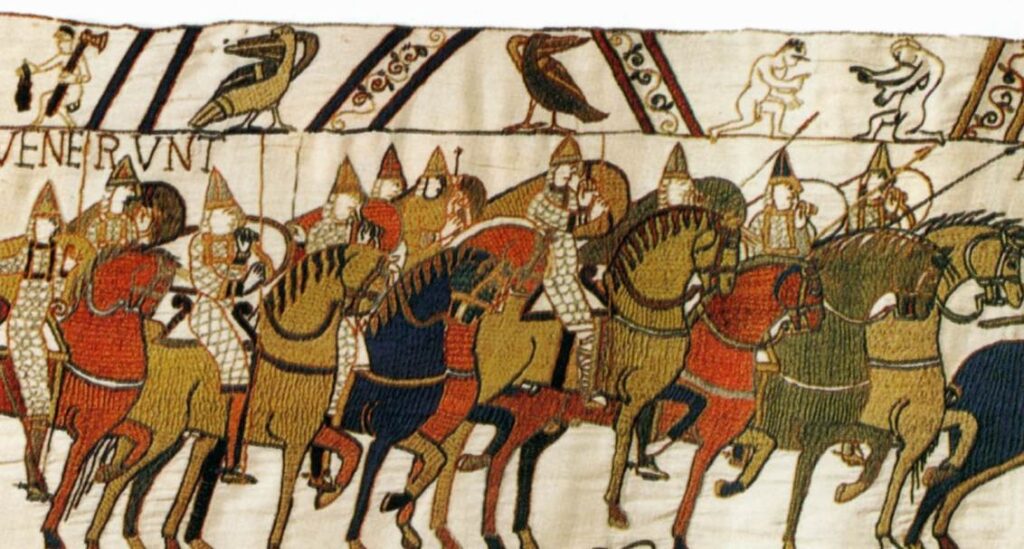

For Marx, the major determinants of historical change lay within the dominant mode of production of a specific social formation. The mode of production involves a labour process (elements: labour power, instruments, materials) carried on at a specific level of technological development by men who work within the context of a specific set of property relationships. In any social formation above physical subsistence level, there is an economic surplus. The strategic social relationship is that between social classes defined primarily (though not exclusively) by whether they control, or do not control, the means of production. Those who control the means of production form the dominant class, and appropriate the surplus. The kind of property relation that exists is itself a significant limiting factor on the kinds of technology that can be developed within a particular productive mode. It is mediated through ideological beliefs and cemented by institutions of domination, notably the state. Thus “the essential difference between the various economic formations of society ... lies only in the form in which … surplus labour is in each case extracted from the direct producer, the labourer”.

[i] It is this, according to Marx, that “determines the relationship of ruler and ruled … It is always the direct relation of the owners of the conditions of production to the direct producers - a relation always naturally corresponding to a definite stage in the development of the methods of labour and thus its social productivity - which reveals … the hidden basis of the whole social structure and with it … the corresponding specific form of the states”.

[ii] Marx left a number of points unclear, notably the exact causal relations deemed to exist between the elements of his model. For instance, the base/superstructure formulation of the 1859

Preface gave the impression of a one-way determination of base on the ideological and political superstructure belied by his more detailed analyses elsewhere. He also left a number of problems unresolved, a major one being, as Marx himself said, “the relations of different state forms to different economic structures of society”.

[iii]