antisemitism

Review: Brendan McGeever, Antisemitism and the Russian Revolution

In January 1918, two months after Soviet power was established in Petrograd, one of the Red Guard units tasked with securing that power on the ruins of the Russian empire entered Hlukhiv, just over the Russian-Ukrainian border, north east of Kyiv. The unit was pushed out of Hlukhiv by the counter-revolutionary Ukrainian Baturinskii regiment within weeks – but soon joined forces with a group of Red partisans who had arrived from Kursk in southern Russia, and took the town back. A pogrom ensued. The Baturinskii regiment changed sides, claiming they had only resisted Soviet power because the “Yids” had paid them to. The Red Guards, thus reinforced, rampaged around the town proclaiming “eliminate the bourgeoisie and the Yids!”

How many of the town’s 4000 or so Jews fell victim is unknown, but it was in the hundreds. Newspaper reports and eyewitnessed accounts detailed how, for two and a half days, families were lined up and shot, their houses were ransacked and Jews were thrown from moving trains. One report described how 140 were buried in a mass grave. There is no doubt that Hlukhiv’s newly-established Soviet authorities were complicit. After two days of constant killing, they issued an order, “Red Guards! Enough blood!” – but then authorised looting. The synagogue was destroyed and the Torah ripped up. The head of the local soviet then demanded payment from the Jewish survivors.

“In the case of Hlukhiv”, writes Brendan McGeever, “Soviet power was secured by and through antisemitism” (page 48). Within days of the massacre, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, who commanded the Red forces in Ukraine, ordered the recomposition of all Red units in Hlukhiv and surrounding areas; those who resisted were to be shot. McGeever judges that this was “likely” a response to the pogrom. He also shows that the Bolshevik centre in Moscow systematically avoided discussing “Red” pogroms publicly. While Jewish newspapers reported Hlukhiv accurately, larger-circulation Bolshevik newspapers failed to identify the “Red” perpetrators.

The Hlukhiv pogrom was a relatively minor precursor to the ferocious wave of terror unleashed against Ukrainian Jews during the chaotic, multi-sided military conflicts of 1919, in which 1-200,000 died. Those pogroms were the climax of a wave that began in 1917, the year of revolution, and amounted to “the most violent assault on Jewish life in pre-Holocaust modern history” (page 2). There is no doubt – and McGeever reiterates it throughout his narrative – that the overwhelming majority of victims in Ukraine in 1919 were killed by “White” counter-revolutionary and Ukrainian nationalist forces, or in territory controlled by them. Neither is there any question that the policy of the Bolshevik leadership, rooted firmly in Russian socialist tradition, was what we might today call “zero tolerance”. McGeever traces how that policy played out in practice.

How is it that the Russian revolution, “a moment of emancipation and liberation”, was “for many Jews accompanied by racialised violence on an unprecedented scale” (page 2)? McGeever answers by focusing, on one hand, on the minority of pogroms committed by (at least ostensibly) “Red” forces, and on the other, on the strengths and weaknesses of Soviet institutions’ response. The strengths, he argues, emanated largely from initiatives by Jewish socialists, including many who remained outside the Bolshevik party in 1917 and joined during the civil war. McGeever’s book is impeccably researched, thoughtfully argued, and – no small thing at a time when academic publishing more and more resembles a sausage machine – well organised and carefully edited. In this review I look at three key issues: the way that antisemitism overlapped with revolutionary politics (e.g. “eliminate the bourgeoisie and the Yids!”); the limits to the Bolshevik response; and the part played by Jewish socialists in combating antisemitism.

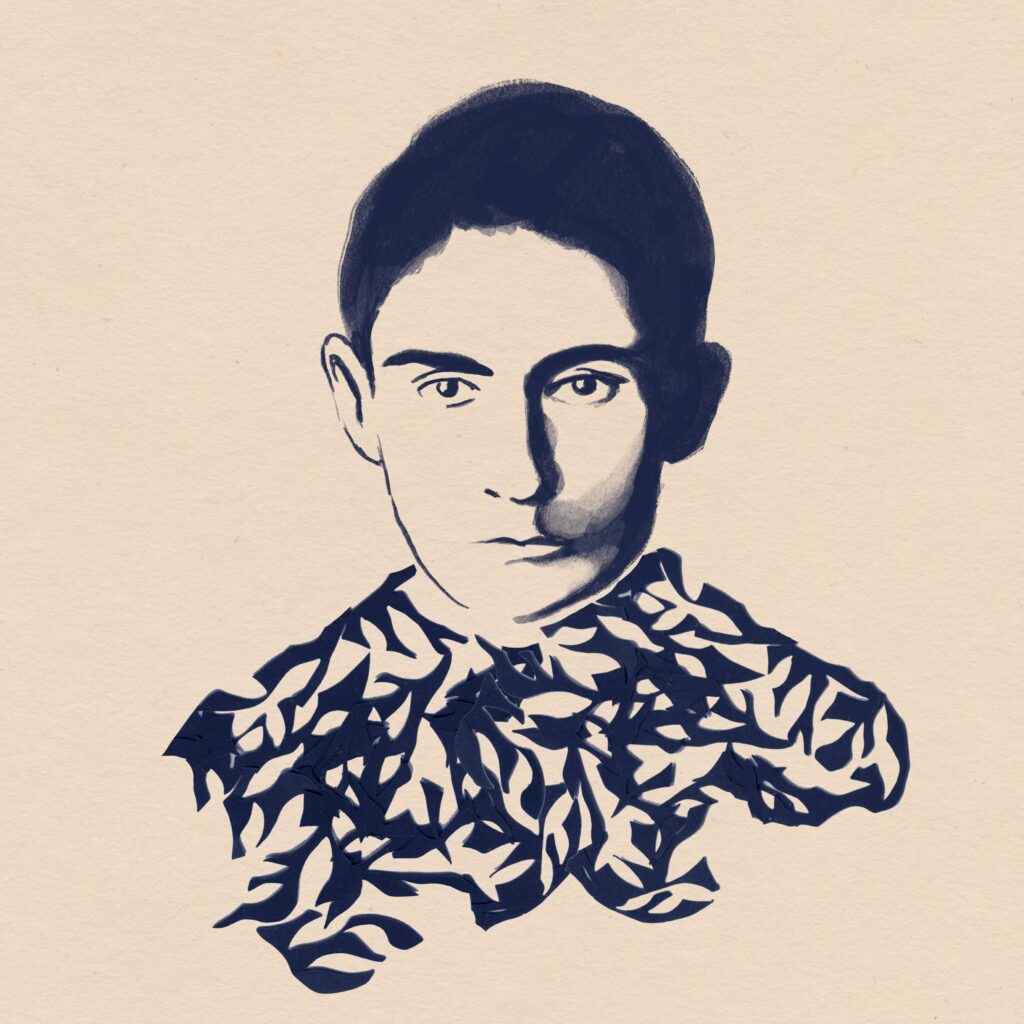

This piece is being made available as a preprint edition of the double-volume Marxism and the Critique of Antisemitism special issue of Historical Materialism. Further additions will still be made before then. The final published version of this text will be made available on the Brill website in the coming months. We ask that citations refer to the Brill edition.All Illustrations are by Natalia Podpora.

“Red” antisemitism

The revolution of February 1917 destroyed the tsarist empire and the legal apparatus of its dictatorship. More than 140 anti-Jewish statutes, which made Jews second-class citizens and confined them to the Pale of Settlement, were swept away, along with legal constraints on peasant farmers, on freedom of speech and assembly, and on much else. But the explosion of social mobilisation, which culminated later in 1917 in mass desertion from the army, land seizures by peasants and factory occupations, had its ugly sides, including a resurgence of antisemitism.

McGeever records that, from the start, the soviet movement issued appeals to combat antisemitism, and warned of its ability to “disguise itself under radical slogans” (page 26). And it needed to: speakers at a street corner rally in Petrograd urged crowds to “smash the Jews and the bourgeoisie!” (as the Red Guards would do in Hlukhiv a few months later) (page 24); people queuing to vote for the Constituent Assembly called on “whoever’s against the Yids” to vote Bolshevik (page 31); absurdly, as Alexander Kerensky left the Winter Palace, when his government fell, he read a slogan, painted on a wall, “down with the Jew Kerensky, long live Trotsky!” (page 32).

Before the revolution, the socialist opponents of tsarism had all resolutely opposed antisemitism, although they were divided as to how to respond to its manifestation among workers. (The Russian left parties seem to strike a contrast with those in France, Germany and Austria, where antisemitism ran rampant not just on the streets but among prominent politicians.[1]) In 1917, anti-Bolshevik socialists, and the Mensheviks in particular, accused the Bolsheviks of harbouring or tolerating antisemitism. McGeever urges that such accusation be treated with caution: under circumstances when the right-wing socialists were siding with the pro-war government, while the Bolsheviks were siding with the fast-radicalising masses, this was easy mud to throw. But the aspirations that underpinned the Bolsheviks’ seizure of power in October – peace, bread and land – can not be neatly fenced off from antisemitism either. “Revolution and antisemitism existed not only in conflict but in articulation as well”, McGeever insists (page 30).

This articulation persisted in the hellish conflict in Ukraine in 1919. McGeever makes a convincing case that, especially (but not only) among Ukrainian peasants, revolutionary hopes overlapped with murderous antisemitism. The peasants, overwhelmingly Ukrainian by nationality, saw towns – with high proportions of Russian and Jewish people, whether workers or middle class – as hostile and foreign. “[T]he ‘cityman’ represented a ruthless profiteer, an oppressor of the poor Ukrainian toiler” (page 91). This perception could turn into hostility to “communists”, who were “urban, non-Ukrainians who stood aloof from peasant life; they were ‘Russian oppressors’ and, above all, ‘speculating Jews’” (page 92). Such prejudices were on one hand fed on by the Whites, but on the other hand could fade into a grotesque combination of pro-soviet antisemitism. “Down with the Yids, down with this Moscow Communist government, long live Soviet power!”, shouted peasants in Poltava (page 92).

The violent culmination of this left antisemitism was the armed incursion led by Nikifor Grigor’ev, a peasant ataman who first allied with the Red army and then turned on it. McGeever quotes his Universal, a manifesto that called peasants to revolt (page 98):

In place of land and freedom they [the Bolsheviks] have subjected you to the commune, to the Cheka, and to the commissars, those gluttonous Muscovites from the land where they crucified Christ. [...] Down with the political speculators! ... Long live the power of the soviets of the people of Ukraine!

In early May 1919, Grigor’ev, having taken Odessa in the name of the Red Army, turned against the Bolsheviks. Over the next 18 days his units perpetrated at least 52 pogroms, in which at least 3400 Jews were killed. McGeever relates, in excruciating detail, how local Soviets, and some Red army units that were supposed to be fighting Grigor’ev – in particular, the notorious 8th Soviet Ukrainian regiment – joined in. In some regiments, communists who opposed antisemitism were heavily outnumbered by pogromists: in the 3000-strong 6th regiment, which carried out a pogrom in Vasylkiv in mid April, a group of communist soldiers who called on their comrades-in-arms not to attack Jews comprised 42 members, falling to 20 during early 1919 (page 125).

McGeever’s excruciating account of “Red” pogroms should give any communist pause for thought. His insight that the social forces on which the Bolsheviks relied were prone to antisemitism – that it was not, as the Bolsheviks claimed, solely an external, “counter-revolutionary” phenomenon (see below) – is essential. Further, in the conclusions to the chapter on Ukraine in 1919, he writes that “antisemitism provided a conduit for [...] partisan Red Army soldiers to make the journey from ‘revolution’ to ‘counter-revolution’”; that in the social formation that supported Bolshevism in Ukraine, “antisemitism was a dominant form of consciousness”; that the Bolsheviks’ attempts to combat this were fraught with difficulties since “antisemitism and ‘Bolshevism’ were often co-extensive projects in the popular imaginary”; and that the Grigor’ev revolt “seemed to represent what many within the Bolsheviks’ social base in Ukraine desired: a populist leftist government that represented ‘true Bolshevism’ or true ‘Soviet power’” (pages 110-111). This left me with questions.

The description of the Ukrainian peasantry, and peasants who at times found themselves in the Red Army, as “the Bolsheviks’ social base” (on pages 92, 94 and 111) over-simplifies a complex, many-sided relationship. The Bolshevik presence in Ukraine was largely urban (through party branches in the towns, who were active in the soviets) and military. As McGeever acknowledges, the Red Army in Ukraine included large numbers of peasants-in-uniform who had transferred directly from defeated White forces and partisan formations. “Although nominally Soviet, the Bolshevik leadership could scarcely be confident of their allegiance, let alone attempt to control them”; the centralisation of the Red Army in Ukraine was “simply impossible” (page 93).

And this was just the start of the problem. Peasant support for the Reds was often constrained not only by antisemitism but by opposition e.g. to compulsory grain procurement and clashing conceptions of what “soviet democracy” might mean. Rural and urban political cultures really were distant from each other. Across Ukraine, and much of Russia, “green” peasant formations resisted both Reds and Whites, or sided with the Reds, only to revolt against them when the Whites were irreversibly defeated. There were Don Cossack Reds under Filipp Mironov who joined the Red Army but, when they pressed demands for political autonomy, were suppressed; there were the left Socialist Revolutionaries (Borotbisty) (mentioned in passing by McGeever) and of course the formations led by the anarchist, Nestor Makhno (mentioned in a footnote).

To investigate these multiple facets of Ukrainian peasant politics would be another book. But McGeever’s book sometimes lacked a sense of this larger context within which the battles over antisemitism were fought. I also wonder whether he attributes more agency to the Bolsheviks than they could possibly have had in Ukraine in 1919. With Grigor’ev, he writes, they “were gambling the future of the revolution on a partisan and highly contentious social base” (page 96), and he quotes Antonov-Ovseenko’s absurdly indulgent view of Grigor’ev. Perhaps further research would show that Grigor’ev was simply playing the Reds, who were unable to do more than acknowledge the poisoned chalice of his support, for as long as it lasted.[2]

Whatever the answer to such questions, they do not detract from the strength of McGeever’s main argument. “Red” pogroms were conducted not only by temporary fellow-travellers such as Grigor’ev, but also by more well-established units, and by local party organisations. Examples McGeever gives (pages 108-110) include pogroms during the Soviet-Polish war of 1920 perpetrated by units of the First Red Cavalry, led by Semen Budennyi, one of the Soviet government’s most trusted forces. Scores of Budennyi’s troops, possibly up to 400, were executed as punishment (page 180).

The Bolshevik response

In 1918, the Bolshevik government in Moscow mounted an emphatic response to the new state’s first wave of pogroms – albeit with considerable delay, between the Hlukhiv massacre in March and the formation of the short-lived Commission for the Struggle against Antisemitism and Pogroms in May. It took further action in 1919-20: in the Red Army, pogromists faced punishments up to and including execution, which in keeping with the prevailing chaos were implemented unevenly and sometimes not at all. Jewish socialists played a leading role in coordinating this response, and I discuss this below. Here I look at McGeever’s arguments about the political limitations of these initiatives, which comprised one of the world’s first state-led anti-racist campaigns.

In early 1919, as antisemitic violence gathered pace, the first senior Soviet leader to take action was Khristian Rakovskii, then effectively head of the Soviet government in Ukraine. He issued an order warning that those spreading “antisemitic propaganda” were subject to arrest, with a specific warning to those in Red Army uniforms of “the most brutal and severe measures” (page 114). This order, issued nearly a year after Hlukhiv, was the first public acknowledgment by a Bolshevik leader that there were Red, as well as White, pogromists. Such frankness in public was an exception to the rule. McGeever shows that the Soviet press was extremely slow to take up the cudgels against antisemitism, and that when it did, it first avoided mention of, and later actually suppressed information about, Red Army involvement.

In Ukraine, the coverage of the anti-Jewish massacres was mixed. In April 1919, as reports of pogroms intensified, local Bolshevik party newspapers regularly denounced antisemitism, but the two largest-circulation Red Army newspapers there published not a single article on antisemitism between them. Jewish communists attributed the problem, in part, to Moscow. In mid-May, with Grigor’ev’s slaughter campaign in full swing, their protests were finally heeded with the first-ever lead article on antisemitism in Pravda, the Moscow-based Bolshevik flagship title. A second, and last, lead article on the subject appeared in June – only after the Orgburo, the day-to-day working committee of senior party leaders pointed out “for the third time” how “essential” it was to speak out (page 128). As for antisemitism in the Red Army, this was effectively “render[ed] invisible”. A table, categorising pogroms in January-August 1919 by type of perpetrator, was sent toZhizn’ Natsional’nostei (The Life of Nationalities), the newspaper of the Commissariat for National Affairs. A column attributing 120 pogroms, with 500 fatalities, to the Red Army, was simply deleted – and the number of killings attributed to Grigor’ev cut from 6000 to 4000 (page 131).

The Bolsheviks’ refusal publicly to discuss antisemitism in the state’s institutions and army was informed by an understanding of it as an external, “counter-revolutionary” force. McGeever points to key statements by Lenin, who called antisemitism the work of “capitalists, who strive to sow and foment hatred between workers of different faiths, different nations and different races”, and Evgenii Preobrazhenskii, who attributed it solely to “the Russian bourgeoisie”, who use it to “divert the anger of exploited workers”. McGeever argues that such “reductive conceptualisations failed to account for the many-sided nature of antisemitism, and, in particular, the way it traversed the political divide, finding expression within the left as well as the right” (page 120).

After the civil war, as the Soviet state consolidated its institutions and control over its territory, this crude view of antisemitism as a weapon wielded by external enemies became standardised. So did the public silence on “Red” pogroms. One of several examples given by McGeever is a book on the Ukrainian pogroms of 1919 by Sergei Gusev-Orenburgskii, published in Petrograd in 1921. It was “heavily redacted by Soviet censors such that each and every reference to Bolshevik and Red Army antisemitism was deleted”, shortening it by 100 pages (page 133). Keeping Red Army antisemitism out of the public domain at all costs became “a well-established practice” (page 135).

The reductive view of antisemitism also disarmed the Bolsheviks before workers and peasants who saw Jews as lazy speculators. “In the popular imaginary, ‘the Jew’ was often positioned in an antagonistic class relation to the ‘working people’”, McGeever writes (page 183). This perception filtered through Soviet and Red Army institutions in numerous ways. Given the circumstances – of being surrounded by an unprecedented racist slaughter – the anti-capitalist discourse used by party propagandists sometimes trod a politically questionable line. What were officials in Moscow thinking when they sent directives in mid-1919, at the height of the Ukrainian nightmare, to “sweep away the speculators who have stolen from you”? What were Red Army commanders in Kyiv smoking when they sanctioned the distribution of posters urging “beat the bourgeoisie”, a wording all too close to the age-old pogromists’ chant, “beat the Yids” (page 184)?

Later on, in the 1920s, McGeever relates how Jewish communists discussed the position of Jews in the Soviet state with reference to the fight for hard work and against speculation, “and ‘Jewish speculation’ specifically” (page 202). Here a key trope of left antisemitism merged with the obsession with “honest labour” and productivity, which became prominent in Soviet discourse as the Bolsheviks strove to put the economy back on its feet and restore labour discipline.

McGeever describes how, during the civil war, local, and even national, Bolshevik officials often retreated before a mass of demands that Russians, rather than Jews, be sent to fill responsible posts, and a constant barrage of unsubstantiated complaints that Jews were avoiding front-line service in the Red Army. He looks at a proposal by Lenin, made in November 1919 when the Bolsheviks were putting together institutional structures in Ukraine, on top of civil war wreckage, to “keep a tight rein on Jews and urban inhabitants, [...] transferring them to the front, not letting them into government agencies (except in an insignificant percentage and in particularly exceptional circumstances, under class control)” (page 193). The proposal was adopted and published in a sanitised version with the reference to Jews omitted. But McGeever argues convincingly (page 195) that Lenin was responding to the widespread belief that Jews were underrepresented at the front and overrepresented in comfy offices. Another recommendation made in Bolshevik leadership meetings was to counter antisemitism in the Red Army by deploying Jewish communists in regiments dominated by peasants, which “would have the effect of reducing counter-revolutionary sentiments among the Red Army milieu” (page 187). To my mind, that was a good suggestion, although McGeever thought that, while motivated by a desire to counter antisemitism, it emphasised “changing Jews” rather than changing those with antisemitic ideas.

This controversy over the deployment of Jews in Ukraine was part of a longer-standing discussion about Jews taking prominent Soviet state positions. Trotsky, the ultimate assimilated internationalist Jew, spoke in 1923 and wrote again in his autobiography in 1930 about how in 1917 he had refused some of the most senior state positions for fear of acting as a red rag to antisemitic bulls chasing “Jew-communists”.[3]

Jewish socialists’ practice

The first Soviet state responses to the 1918 pogroms came at the end of April, in Moscow, when the regional government body (Moscow Sovnarkom) coordinated a propaganda campaign, and called on the Cheka (extraordinary commissions, the embryonic security police apparatus) to act against pogroms. McGeever shows that these actions were preceded by, and pushed forward, by a group of non-Bolshevik Jewish socialists. In March 1918, in the midst of an unprecedented revival of Yiddish culture after the 1917 emancipation, these Yiddish speakers – members of the Poalei Zion, the United Jewish Socialist Workers Party and the Left Socialist Revolutionaries – formed the Moscow Evkom (Jewish committee) (page 56). They protested vehemently at the lack of central action against rising antisemitism; on 11 April their representative, David Davidovich, addressed the All Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK, effectively the government). “It was the non-Bolshevik Jewish socialist who pressed antisemitism on to the agenda of the Bolshevik leadership. This dynamic would resurface time and again” (page 66). For the Jewish socialists,

[T]he slaughtering of Jews was not epiphenomenal, nor was it a mere facet of the revolutionary process. It was the fundamental question in the spring of 1918, and it shaped their own engagement with the revolution during this period.

The earth-shattering political events that followed – the outbreak of the Russian civil war, the failed German revolution of November 1918, and the Proskuriv pogrom by the Whites in mid-February 1919 – galvanised Jewish socialists. The Jewish groups – like many other socialist parties across the old Russian empire – split, usually along pro- and anti-Bolshevik lines. The Jewish communists, retaining varying degrees of autonomous organisation, merged into the Bolshevik party. They called on Jews to join the Red Army to fight Whites and pogromists. As one of these groups, the Komfarband, declared at its founding conference in May 1919, the pogroms had “not been able to stop the revolutionary process”, but on the contrary, had raised “the level of revolutionary energy among the urban [Jewish] poor, before whom stands the prospect of physical extermination” (page 148).

The Jewish communists’ response to the pogroms was underpinned by an “ethical imperative”, in McGeever’s phrase (pages 85, 160-161, 171). They spoke from the subject position of “racialised outsiders”, a concept he borrows from the sociologist Satnam Virdee. There was a tension between this and the approach of most Bolsheviks, for whom the fight against pogroms was subordinate to the larger struggle against counter-revolution. This was starkly evident at a conference of the Evsektsiia (Jewish sections of the Bolshevik party) on 1 June 1919. Ia. Mandel’sberg, a Komfarband representative, interjected in a debate about the sections’ orientation to the Jewish middle class, that “the main enemy of the Jewish working class is antisemitism, and to fight it we need urgently to outline a set of concrete measures”. Semen Dimanshtein, head of the Evsektsiia and more ideologically committed to Bolshevism, retorted that “antisemitism is not a special Jewish question, as Mandel’sberg thinks ... it is a plague on the revolution; it is the slogan of the counter-revolution” (page 163).

None other than Mikhail Kalinin, the chairman of the VTsIK and titular head of the Soviet state, who was attending the meeting as a guest, intervened, implicitly supporting Mandel’sberg. He pointed out: “There are no other people who have shed as much blood as the Jewish people have ... no honest person can remain indifferent to the current mass murder of the Jews.” Arkadii Al’skii, like Dimanshtein a committed Bolshevik, refuted Kalinin’s argument, insisting that “Jewish communists fight under the banner of the Russian Communist Party against all enemies of the revolution, no matter who they are”; they approached the issue of antisemitism not as “Jewish national-Communists” but as “Communist Jews who have no connection with the Jewish bourgeoisie” (page 165). Kalinin, to the astonishment of the meeting, walked out. Would that Mandel’sberg and others had been able to adapt a slogan from the future: “Jewish lives matter.”

It is to McGeever’s credit that he has recovered these pioneering discussions on what we would today call the politics of anti-racism. The conversations were cut short. In the early 1920s, many of the most prominent Evsektsiia activists were dispersed, to work in Soviet departments or universities, or to continue their struggle in other countries. By the time of the major post-civil-war state campaign against antisemitism, launched in 1926, the Soviet state had changed beyond recognition. In the run-up to the first five year plan and forced collectivisation, antisemites were added to an “ever-growing list of harmful enemies, alongside kulaks, priests, wreckers, speculators and hooligans”, McGeever writes (page 214). The campaign was motivated less by a desire to protect Jewish life than by the larger state project of targeting threats to the regime. Including much of the peasantry, it could be added.

Concluding comments

Antisemitism and the Russian Revolution is welcome because of the care with which McGeever examines the history of the revolution as an interaction between political forces – the Bolshevik party, and the Jewish socialists who fought alongside it – and society. The particular problem of antisemitic violence is abstracted from the general process of revolution and civil war, into which it has often been subsumed. For communists, McGeever’s work is especially timely. We live at a strange conjuncture, when hero-worship of the Bolsheviks has been resurrected in the mythical construct of “ecological Leninism”.[4] Rather than yearning for 20th century heroes to resolve our 21st century problems, McGeever focuses soberly on how the Bolsheviks, and others, dealt with the life and death problems in front of them.

The internationalism with which the Russian revolution became associated, its function as a focus for anti-imperialist struggles throughout the twentieth century, now appears to be one of its most significant legacies. The Bolsheviks “can not claim exclusive credit for putting the struggle against colonialism on the political agenda of the 20th century”, Steve Smith concludes in his recent history of the revolution, but it was the Communist International (Comintern) that “popularised militant anti-imperialism” and served as a training ground for leaders of national liberation struggles.[5] Without minimising the Soviet Union’s imperial dimension, Smith adds, the Soviet “commitment to affirmative action and empowerment programmes for ethnic minorities” looked forward to much that changed in the second half of the twentieth century elsewhere. Priyamvada Gopal, in her history of resistance in the British empire, argues that the overthrow of tsarism had “a galvanising influence on resistance to imperial rule in many parts of the world”; the Comintern “was a significant catalyst” to the process of resistance, even though its vacillations were sometimes part of the problem.[6]

Against this background, McGeever’s focus on the first and most immediate manifestation of national or racial oppression during the revolution – the frightful assault on Jews – seems especially relevant. His account of the overlap between the emancipatory hopes raised in millions of people by the revolution and the poison of antisemitism is compelling. As for the socialist actors in his story, he shows how the Bolsheviks’ efforts to counter antisemitism were hamstrung not only by the dire circumstances, but by their narrow, ideologised understanding of how antisemitism worked. Kalinin’s implicit rejection of that approach, pushed by the Jewish socialists at the Evsektsiia meeting in June 1919, really stuck in my mind. In many ways the Jewish socialists’ struggles – alongside, and sometimes in sharp disputes with, the Bolsheviks – foreshadow the struggles that Gopal describes, by African, Indian and Caribbean socialists with their British and other counterparts later in the twentieth century. Working over the lessons of those struggles, notwithstanding the real human tragedies that surrounded them, is inspiring.

[1] See Hannah Arendt on “Leftist Antisemitism”, in The Origins of Totalitarianism (London: Penguin, 2017), pp 53-65

[2] A standard account of the civil war is Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War (London: Allen & Unwin, 1987). Trotsky, when he arrived in Ukraine in May 1919, reported to the Bolshevik central committee that “the prevailing state of chaos, irresponsibility, laxity and separatism” exceeded the most pessimistic expectations. M. Meijer (ed.),The Trotsky Papers I (1917-1922) (The Hague: Mouton, 1964), p. 431.

[3] Trotsky, My Life, chapter 29 <https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/mylife/>; Valentina Vilkova,The Struggle for Power: Russia in 1923 (New York: Prometheus Books, 1997), pages 183-184

[4] On “ecological Leninism”, see for example Andreas Malm, Corona, Climate, Chronic Emergency: War Communism in the Twenty-First Century (London: Verso, 2020), and this reviewer’s comments in: S. Pirani, “The direct air capture road to socialism?”,Capitalism Nature Socialism, March 2021.

[5] S.A. Smith, Russia in Revolution: an empire in crisis 1890-1928 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017)

[6] Priyamvada Gopal, Insurgent Empire: anticolonial resistance and British dissent (London: Verso, 2020), p. 211

Victor Serge: Three Writings on the Jewish Question and Antisemitism, 1943-47

By Way of an Introduction: The Middle Ages Chasing Us by Claudio Albertani

– Let us be allowed to laugh, madam, about this demented undertaking, the universal extermination of the Jews,

They won’t succeed, they are too many, and besides, the Rich will always be saved, and they’ll say: we are Aryans,

They will be believed because they will pay,

And the poor, madam, Jews or Aryans, are nothing.

– Victor Serge, ‘Marseille’ (1941)

This piece is being made available as a preprint edition of the double-volume Marxism and the Critique of Antisemitism special issue of Historical Materialism. Further additions will still be made before then. The final published version of this text will be made available on the Brill website in the coming months. We ask that citations refer to the Brill edition.All Illustrations are by Natalia Podpora.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the well-known German socialist August Bebel defined antisemitism as ‘the socialism of fools’. Today the situation has changed. If it is true, in fact, that there are only a few of us left to be socialists – or libertarians, in my case – the fools have reproduced themselves in geometric progression. We live in a sick society and, among the many forms of sterile resentment that corrode it, racism – of which antisemitism is an expression – continues to occupy a significant place. So-called social networks, which in fact have very little social about them, overflow with stereotyped images of foreigners bearing who knows what evil essence supposedly marking them apart from other human beings. Sometimes, the clueless who say and write such nonsense call themselves ‘leftists’.

At the same time, we are witnessing the spread of the paradigm of antisemitism, now used against any individual or social group that is considered ungovernable. In the West, the ghetto and the pogrom – a word of Russian origin, indicating the massive lynching of Jews and the plundering of their property – are treatments historically reserved to Jews, as well as gypsies and revolutionaries. Today, walls, barriers, barbed wire, fences and enclosures have multiplied all over the world. These are so many ominous signs of the new Middle Ages, the warning signs of which Victor Serge (Brussels, 1890-Mexico City, 1947), the author of the texts we present here, observed in the 1930s and 1940s.

A dreadful mixture of irrationalism, cult of hierarchy, tradition and modernity, fascism was the axis around which the history of the 20th century turned, and remains one of the key facets of the first twenty years of the new millennium. Like in its classic variant, the current fascism exploits the never completely extinguished impulses of nationalism, intolerance and xenophobia. With one difference. Discrimination now no longer concerns mainly the Jews, but is directed above all against the populations that Capital fears for different reasons, but of which it has a terrible need.

There are, first of all, immigrants, now subjected to various forms of segregation ranging from forced residence to actual concentration camps. But there is much more. In a mocking replication of history, Israel has built an immense ghetto in Gaza where it locks up Palestinians just for being Palestinians, in the same way as the Nazis segregated Jews just for being Jews. In Turkey and elsewhere those afflicted by this plague are the Kurds, and in the Americas the blacks or the indigenous, guilty, like the Maya of Chiapas, of living in territories rich in oil and natural resources. The list is long and could continue, but it would take us off-topic.

It is worth asking why this brief selection of writings on the Jewish question and antisemitism is being published here. Besides the fact that, to our knowledge, these three texts have never appeared before in English, this is not just an exercise in historiography. It is also this, but perhaps it stems even more from the need to shed light on our present, on the particularly insidious forms of totalitarianism that characterise the society in which we live and that were only in its infancy in the 1940s.

An attentive observer, Victor Serge belonged to the scattered groups of intransigent militants – libertarian Marxists, anarchists, Trotskyists, councilists, Bordigists and independent socialists – who, despite the great differences that separated them, had managed to maintain an admirable lucidity in the midst of the ‘midnight of the century’, when the revolutionary cycle was over and so-called bourgeois civilization showed its true murderous face.

Each in their own way, those militants had understood the essential features of the great transformation underway, showing the convergences, as well as the differences, between fascist totalitarianism, Stalinist totalitarianism and the so-called ‘Western democracies’. It should be remembered that in a 1933 letter, written shortly before his last arrest, Serge had been one of the first to characterise the Soviet Union as a totalitarian country.

These three articles are each occasional in character — something which, far from limiting their interest, increases it. In fact, besides being a historian, a novelist and a poet, the author of Memoirs of a Revolutionary – a cult book, translated in dozens of languages and still indispensable to understanding the epic of the betrayed revolutions of the first half of the 20th century – was also a great chronicler, a scrupulous narrator of the tragic events that took place before his eyes. Unlike many other intellectuals and militants of that time, he perceived the deadly consequences of Nazi antisemitism, so to speak, in real time.

The first text, undated but certainly written in the first months of 1943, brings together brief notes, probably intended to be part of a larger essay, and treats antisemitism, as a general problem of counterrevolution, within the framework of the Russian 1905 and especially of Nazi totalitarianism. The reaction, Serge writes, is about destroying the dignity of the human person and creating deadly psychoses in the context of social warfare.

‘The Jewish Question’ offers Serge’s answers to a questionnaire sent him in 1944 by Babel, a splendid Chilean magazine edited by Enrique Espinoza – pseudonym of Samuel Glusberg –, a Jew by birth and a Trotskyist sympathizer. Faced with the spread of antisemitism, Serge felt compelled to mount a real apologia for Jewish culture by mentioning Marx, Freud, Einstein, Zweig and others, all authors of universal stature. Antisemitism, he concludes, anticipating Hannah Arendt’s studies, demands a psychological and social analysis and must be considered in the context of the destruction of humanism that was, and still is, one of the characteristic features of our time.

‘Opinions and Facts on the Jewish Question’ – undated (and we do not know if it was ever published), but undoubtedly drafted after 17 August 1947, the day of publication of Arthur Koestler’s ‘Letter to a parent of a British soldier in Palestine’ that Serge reviews, and prior to 17 November, the date of his sudden death –, although showing disagreement with the opinions in favor of Zionist terrorism expressed by Koestler, also displays, it must be admitted, an insufficient sensitivity to the incipient Palestinian question and an excessive severity towards the Muslim cause in the Middle East.

These are, it seems to me, all themes of tremendous topicality.

Mexico City, November 2021 (Year II of the healthcare dictatorship)

* * *

ANTISEMITISM[1]

[early 1943 ca.]

Nazi antisemitism heightens, with all the abominable violence of a crime of historically unique magnitude, the new character of this war and its aspects of civil war.

During the imperialist war of 1914-18 there was no antisemitism because European humanism, which did not exclude either wars between states or class wars but did tend to impose its own laws upon them, was not itself put into doubt. Today this humanism is struck at its foundations: in totalitarian systems the Christian spirit, the scientific spirit and the socialist spirit are destroyed or mortally disfigured.

Contemporary antisemitism was born in the social struggles in Russia at the time of the first revolution (1905). The pogroms were then organised by the imperial authorities and the monarchical leagues in order to offer a diversion to popular violence. The old regime wanted scapegoats and, in order to better subjugate mankind through the repression of the revolutionary movement, sought to accustom the masses to collective crime, perpetrated against a defenseless religious minority.

In 1918-21, during the Russian civil war, the monarchist and nationalist gangs started the extermination of the Jews. The victory of the revolution put an end to Russian antisemitism.[2] The Protocols of the Elders of Zion[3] were fabricated in Russia by visionary mystics and policemen. They constitute one of the ideological elements of Nazi antisemitism.[4]

The motives behind the antisemitism of the Third Reich are those of the counterrevolution itself. It is, once again, a question of directing the violence of the masses against an unarmed minority of the nation. In order to better destroy the dignity of the human person, it is necessary to accustom society to the humiliation, spoliation, and extermination of a social category arbitrarily chosen precisely because it is defenseless. This means unleashing and fostering the murderous psychoses most indispensable to the social war waged by reaction (even despite the fact that they are clearly contrary to the interests of Nazi neo-imperialism in the world war). From the economic point of view, this means expropriating a wealthy minority of the nation without, however, directly threatening the capitalist classes as a whole, and irrevocably binding a large number of executors to the Nazi system, through their criminal complicity.

A multitude of testimonies tells us that the German people, as a whole, are unaware of most of the crimes of antisemitism, and that when they do know them they are not at all complicit in them. These crimes are those of the Nazi system. They will one day bring down dreadful and deserved punishments on their perpetrators, for which we count first of all on the German people themselves. Born out of the civil war, antisemitism remains a factor for civil war.

According to the incomplete information in our possession, the extermination of the Jewish population in occupied Russia is more or less complete. Belarus and Ukraine had over two million Israelite workers. The fact that this population bound to martyrdom was not completely evacuated during the invasion, when there could be no doubt as to its fate, we consider a real crime. In Poland the systematic extermination of the Jewish population – over three million inhabitants – began in 1942; the extermination of the 400,000 inhabitants of the Warsaw ghetto began in July 1942 and, in December, the ghetto had no more than 40,000 survivors. Most of Poland's Jews would have been killed by asphyxiation trucks.

These nameless horrors attest to the fact that elementary human sentiment, acquired over long centuries of civilisation, was deliberately trampled upon by Nazism. They would be sufficient to demonstrate an essential difference between this war and all those that preceded it. Since antisemitism and racial discrimination were, in all countries of the world, the prerogative of reactionary movements, these crimes stand as a condemnation of the international reaction.

THE JEWISH QUESTION[5]

(12 October 1944)

We posed the following questions to some writers from different countries:

1. Could you summarise for us some of your significant personal experiences pertaining to your fellow citizens of Jewish descent?

2. Do you accept any racial discrimination against or in favour of the so-called sons or grandsons of Israel?

3. What do you think about antisemitism and its consequences in today’s world?

Here are some of the answers we received:

(…)

1. My experience has led me to regard the Jewish nation as one of the most gifted. In the modern world, divided by social struggles, it has produced great capitalists, skilled merchants, high quality intellectuals, a multitude of socialists and revolutionaries, thinkers whose contribution to civilisation has been essential. This is to say that, though it is socially divided like all other nations, it has distinguished itself in every field. If one considers the masters of thought of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th, one is struck to see that the Jews have provided incomparable figures, whose influence has been and remains immense: such as Karl Marx, founder of scientific socialism; Sigmund Freud, one of the founders of modern psychology; Albert Einstein, innovator of modern physics and scientific philosophy; Leon Trotsky, man of thought and action... Other names also deserve mentioning here, such as the French philosopher Henri Bergson, the socialist Lévy-Bruhl, the writer Stefan Zweig, the critic Georg Brandes... It is unfair to mention only a few names; we realise that the contribution of the Jews to the intelligence of our time has been powerful and fruitful.

I personally met many Jews belonging to every social condition. I met some who were heroes and other who were more than unpleasant; but, after all, all of them were intelligent and active.

2. It seems to me that with regard to the Jews it is more appropriate to use the term nation or people rather than race, because today there are no pure races (unless we are satisfied with broad divisions of the human species into white, black, yellow and red races). The Semitic family includes Arabs, Bedouins, Ethiopians, and Jews, but from its origins it has undergone endless mixing; Ethiopians are black or nearly so, Arabs, Bedouins, and Jews are white. A historical and religious tradition has maintained the Jewish people for millennia through many conquests and much mixing. In the early Middle Ages there was in Russia, on the Volga, a Khazarian empire, probably Mongolian, who converted to Judaism. There are Chinese, Tartar and other populations that practice Judaism. Finally, after the disbanding of the kingdom of Israel, in the first century of our era, the Jewish colonies of Europe, the Middle East and America have undergone so much ethnic mixing that there are blond, red, brown and black Jewish types, sometimes recognizable and sometimes indistinguishable from other European types. In this case, to speak of racial discrimination is to fall into reactionary absurdity by adopting an anti-scientific attitude.

Perhaps it would not be superfluous to remind that the spiritual and social revolution that has left the deepest trace in the whole development of European civilisation started from Judea, originally stirred by great Jews, the more famous of whom is Jesus of Nazareth… To say it schematically, the origins of our civilization are Greek-Roman and Jewish.

Another important consideration arises in favour of the Jews and tends to explain their great intellectual quality. They are the only white people who have, like the Hindus and Chinese, a tradition of civilisation going back to 4,000 years. The white peoples who founded the earliest civilizations of the Middle East and the Mediterranean left no direct lines of descent. At the time when the Jews were already an old cultured people, endowed with a long history and religious thought that was arriving at a monotheistic philosophy, the Indo-European peoples were still but primitive peoples.

3. Antisemitism requires a psychological and social analysis that I cannot outline here. In practice, it arose in Russia during the revolution of 1905, as a pretext of the royalist reaction concerned to divert the violent instincts of ignorant and destitute masses against a defenseless religious minority. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion were deliberately fabricated by Russian police with the help of some visionaries (this story has been reconstructed in all its details). The function of Nazi antisemitism was the same: at a time when German capitalism was going bankrupt, it worked to redirect against Jewish capitalism the anti-capitalist sentiment of the masses; to divert the sadistic instincts of part of the disorientated masses into aggression against a defenseless minority; to create an irrational psychology at a time when rational thought was becoming dangerous to governments; to create through violence, spoliation and massacres the terrible bond of criminal complicity between all participants in antisemitism (in order to cement its ability to resist); to degrade mankind in general in order to more easily break its opposition to the totalitarian regime. It goes without saying that after humiliating and murdering the Jew in the street, it becomes easy to humiliate and murder anyone; the precedent is set, a feeling of powerlessness and degradation has set in,humanism is destroyed. The politically utilitarian aspect of Nazi antisemitism also flows from the fact that Hitler’s racism, by concluding an alliance with Japan,[6] abandoned the yellow peril doctrine that had been the doctrine of the beginnings of Germanic racism and, notoriously, of Wilhelm II. The counterrevolutionary (anti-socialist) character of antisemitism stems from the fact that in Russia, after the bloody pogroms of 1905-06 and the massacres of the Jews of Ukraine at the hands of reactionary gangs in 1918, the victorious revolution put a definitive end to antisemitism, without real effort and almost without repression.

In Russia, Poland and occupied Europe, the Nazis have exterminated several million Jews, i.e., skilled and hardworking Europeans, with scientific organisation, by means of asphyxiating trucks, etc. (As long as they could, the Nazis concealed from the German people the extent of this crime.) In this way, they caused irreparable harm to Europe and to the entire civilised world for an extended period of time. By cultivating an irrational ideology based on murder, they managed to awaken and mobilize in the whole world those sadistic instincts that Christian civilisation, scientific culture, European humanism and socialism seemed to have tamed. The psychological and social consequences of this degradation of modern man will certainly persist long after the liquidation of Nazism and the punishment of the guilty. This means that in the struggle for the greatness and liberation of man, for a new humanism, the battle against conscious or unconscious antisemitism will be long, difficult, unceasing, and will constitute one of our most imperative duties.

OPINIONS AND FACTS ON THE JEWISH QUESTION[7]

[August 1947]

The Statesman and Nation, London

The Socialist Leader, London

The New Leader, N[ew] Y[ork]

Arthur Koestler does not figure on the roster of the contributors to the old English liberal weekly The Statesman and Nation. Koestler’s position on totalitarianism is well known; on the other hand, the liberal weekly is full of indulgence and sympathy for the likes of Tito, Bierut and Vyshinsky...[8] So, we are surprised to see in The Statesman [and Nation], by way of an exception, a remarkable ‘Letter to the father of a British soldier stationed in Palestine’ signed by Koestler.[9] In a few columns, the Palestinian question is dealt with thoroughly, forcefully and clearly, by a masterful writer who offers us a fresh demonstration of civic courage. Today, courage is not such a common commodity that we are not at least a little heartened to see it at work. Koestler, a Hungarian Jew and naturalised Englishman, and moreover a former communist who has become – by this very fact – anti-Stalinist, could express himself in London, on such a subject, without the slightest reticence, and his beautiful prose is being published by liberals who, as far as international politics are concerned, are his adversaries! Freedom of opinion and intellectual loyalty occupy a place of honor... Koestler declares himself an advocate of terrorism in Palestine and emphasises its irrefutable, passional motivation. We believe that on this point he is wrong, and his own wiser leanings lead him to advance reservations ‘on the way terrorism is being applied’. In this case everything depends on the nature of the acts, that is, on the ‘way’ of doing things and not on the principle. Today no one will be outraged by the street execution of an executioner or a military brute guilty of the death of some Dachau survivors. But does Jewish thought, Jewish ethics, the cause of the Jewish people and all the oppressed of the world justify the hanging of two young British soldiers who were not personally responsible for anything? Koestler is careful not to assert this, and neither do we. The Jewish cause is too important to be so ill-served…

Koestler highlights the fact that the ruling Labour Party is failing in all its commitments to the Jewish people. It must be noted that the LP, while intelligently and firmly supporting the most arduous struggle for the salvation of devastated, weakened and threatened England, shows, by its foreign policy, a singular mediocrity in a variety of serious circumstances and thus alienates much sympathy in the world. Its attitude toward the Palestine issue, in reality determined by old colonialist interests and aggravated by a military and bureaucratic personnel of the worst kind, is scandalous. We will note, moreover, that the British military authorities in Italy have recently handed over to the Russian political police several groups of Russian refugees guilty only of fleeing tyranny.[10] We will note, finally, that the LP’s political incapacity caused the failure of the international socialist conference in Zurich, foolishly favoring the manoeuvres of the pseudo-socialist, subservient, police-state regimes of Poland, Yugoslavia, Romania...[11]

The Socialist Leader, organ of the Independent Labour Party (London), soberly points out that the Muslims of India have forced the partition of the country into two states, and that such partition weakens them and even risks pitting them against each other. They got Pakistan. In Palestine, on the contrary, the Muslims oppose a territorial division! Inconsistency? This word would be indulgent. Let us note that from Karachi to Casablanca the Islamic world, governed by reactionary elements whose mentality seems to have stopped in the tenth century of our era, provides the most striking demonstrations of a political immaturity that is all too dangerous... Pakistan’s independence is being inaugurated with the massacres of Hindus and the kidnapping of Hindu women (by the tens of thousands). And let's turn to the information published by N[ew] Y[ork]'s The New Leader.NL correspondent M[ark] Alexander summarily reports his impressions of a trip from Istanbul to Cairo. He notes the extraordinary propaganda effort of the USSR in the Muslim countries and the strangulation of the freedom of press in the Arab countries which are members of the U[nited] N[ations] and in Turkey,[12] where one must nevertheless note a slight improvement in the situation... In Iraq some twenty newspapers have been suppressed during the last two years, including three Communist sheets, but no one of the fascist sheets! In Syria the director of the Reuter Agency has been sentenced to six months in prison and a heavy fine for disrespecting the president of the republic! In Lebanon, half of the newspapers in Arabic, French and Armenian have just been suppressed, and the correspondents of the Reuter Agency and the Palestine Post have been expelled. What a happy republic! In Egypt eleven journalists have just been arrested for criticizing the attitude of the Egyptian delegation to the UN, and persecution of the press is constant. What a happy kingdom! In Palestine there is a censorship of the press in the most insidious form. Every newspaper has a censor in its editorial office and incurs various penalties if it allows itself to publish anything about ‘debatable subjects’, e.g. about the Nazi Mufti in Jerusalem and the British regime. It is forbidden to call a Nazi war criminal, antisemite, proven accomplice of Hitler-Himmler-Streicher, by his proper name! In Saudi Arabia there is only one newspaper, that of the government.[13] Thus everything is going on very well...

[1] ‘L’antisémitisme’, a two-page French-language typescript, undated and unsigned. It is kept in an untitled dossier containing other short texts on anarchism, Trotskyism, etc., that remained at the draft stage. The French original was published for the first time in V. Serge, L’extermination des Juifs de Varsovie et autres textes sur l’antisémitisme, Paris: Joseph K., 2011, pp. 89-91.

[2] On 25 July 1918 the Council of People's Commissars of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic adopted a ‘Decree on the Struggle against Antisemitism and Anti-Jewish Pogroms’, appearing in Izvestiya No. 160 of 30 July. That struggle, however, was partially unsuccessful insofar as antisemitism periodically resurfaced in Soviet Russia, particularly in the Red Army during the Civil War and the Russo-Polish War. See especially Nicolas Werth, ‘Dans l’ombre de la Shoah: Les pogromes des guerres civiles russes (1918-1921)’,Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah, No. 189, July-December 2008, pp. 319-57; Oleg Budnitskii,Russian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917-1920, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012; and Brendan McGeever,Antisemitism and the Russian Revolution, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. A new and more substantial wave of ‘Soviet’ antisemitism gained momentum again in the 1930s, during the Stalinist period.

[3] Besides the classic work of Norman Cohn, Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion [1967], London: Serif, 2005, on the history and worlwide impact of that book see in particular Hadassa Ben-Itto,The Lie that Wouldn’t Die: The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, London: Valentine Mitchell, 2005; Stephen Eric Bronner,A Rumor About the Jews: Reflections on Antisemitism and The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000; Esther Webman (ed.),The Global Impact of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: A Century-Old Myth, London: Routledge, 2011; and Michael Hagemeister,The Perennial Conspiracy Theory: Reflections on the History of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, London: Routledge, 2022.

[4] On this specific aspect, see Pierre-André Taguieff, Hitler, les Protocoles des Sages de Sion et Mein Kampf: Antisémitisme apocalyptique et conspirationnisme, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2002; and Randall L. Bytwerk, ‘Believing in“Inner Truth”’: The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in Nazi Propaganda, 1933–1945’,Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Vol. 29, No. 2, Fall 2015, pp. 212-29.

[5] ‘La question juive’, a two-page French-language typescript from the Victor Serge’s archives in Mexico City, now in the Victor Serge Papers at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library Repository, New Haven (Connecticut), Box 5, Folder 260, Call Number GEN MSS 238, Series II. It was translated into Spanish and published in Babel. Revista de arte y crítica, Vol. 6, No. 26, Santiago de Chile, March-April 1945, pp. 61-4. These are the answers to a questionnaire that the magazine had sent to various writers ahead of the publication of that issue, specifically devoted to the Jewish question. The three questions devised by Babel are reproduced here in italics. The French original of Serge’s answers has been published in V. Serge,L’extermination des Juifs de Varsovie…, cit., pp. 84-8, but the editor of that book (Jean Rière) was unable to reproduce the questions as he did not find that issue ofBabel. That Chilean magazine was edited, under the pseudonym of Enrique Espinoza, by an Argentinian leftist intellectual of Russian origins, Samuel Glusberg (1898-1987). He had visited Trotsky in Mexico in 1938, became a Trotskyist sympathizer, and subsequently started a correspondence with Trotsky himself and with Jean van Heijenoort (see Nicolás Miranda,Historia del trotskysmo chileno 1929-1964, Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Clase contra Clase, 2000, pp. 29-37). On Serge’s collaboration with the magazine, see Claudio Albertani, ‘“A la sombra de los nopales crueles”’: Victor Serge, América Latina y la revistaBabel’, Revista de Humanidades de Valparaiso, Vol. II, No. 4, 2nd semester 2014, pp. 7-20.

[6] On 27 September 1940 Nazi Germany, fascist Italy and imperial Japan had signed in Berlin the Tripartite Pact, a military-political agreement that established the so-called ‘Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis’. In the midst of World War II, it recognized their respective spheres of influence within the framework of the ‘new world order’: Europe to Germany and Italy, and the Far East to Japan. As far as the latter was concerned, the pact utterly clashed with Hitler’s original racist dogma of the inferiority of all non-Aryan peoples.

[7] ‘Opinions et faits sur la question juive’, a two-page French-language typescript, undated and signed ‘S.’, so far unpublished in any languages, from the Archives of the Centro Vlady at the Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, in Mexico City, Fondo Victor Serge, file 10, dossier 106. Another copy is to be found in the Victor Serge Papers at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library Repository, New Haven (Connecticut), Box 4, Folder 234, Call Number GEN MSS 238, Series II.

[8] The Stalinophilia of that journal had already surfaced during the second half of the 1930s, e.g when its editor Kingsley Martin refused to let one of his journalists review Trotsky’s The Revolution Betrayed and to publish George Orwell’s famous article ‘Spilling the Spanish Beans’ because he harshly criticized of the Stalinist repression of the anarchists and thePartido Obrero de Unificación Marxista carried out by the Stalinists after the May Days of 1937 in Barcelona. See Bashir Abu-Manneh, Fiction of the New Statesman, 1913-1939, Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2011, pp. 167-71. Such orientation softened during the Nazi-Soviet pact (August 1939 to June 1941), but was resumed immediately after the German attack against the Soviet Union, when Stalin became a military ally of Great Britain.

[9] A. Koestler, ‘Letter to a Parent of a British Soldier in Palestine’, The New Statesman and Nation, 16 August 1947, pp. 126-27.

[10] A reference to the highly controversial Operation Keelhaul, which, on the basis of the 1945 Yalta agreements, provided for the forced repatriation to the USSR of the Russian POWs interned in various Italian prison camps after the end of World War II. Beginning in August 1946, the operation ended in May 1947. See Julius Epstein, Operation Keelhaul: The Story of Forced Repatriation from 1944 to the Present, New Greenwich: The Devin-Adair Company, 1973; Nicholas Bethell,The Last Secret: Forcible Repatriation to Russia 1944-7, London: André Deutsch Limited, 1974; and Nikolai Tolstoy,Victims of Yalta: The Secret Betrayal of the Allies 1944-1947, New York: Pegasus Books, 1977. Since the overwhelming majority of these Russian prisoners had fought in the ranks of the Nazi army or collaborated with theWehrmacht, it is clearly wrong to argue – as Serge did – that they were merely refugees ‘guilty only of fleeing tyranny’.

[11] At that conference, held from 6 to 9 June 1947, the British Labour Party had supported the German social-democracy’s ‘nationalist’ refusal to enter a ‘united front’ with the German CP. Having been invited to attend the conference as observers, SPD delegates met a fierce opposition from Eastern European socialists, especially the Poles, on that specific point. Although backing the SPD, the LP acted behind the scenes in the opposite sense for fear of a final break with the Easterners. The Labour delegation ‘appears to have pressured the Swiss to abstain on the vote, helping to deny the SPD a two-third majority’, thus objectively favouring the pro-communist Eastern European socialists. Moreover, while approving in principle the idea of rebuilding a socialist International, LP representatives had opposed its immediate proclamation as ‘premature’. See Talbot C. Imlay, The Practice of Socialist Internationalism. European Socialists and International Politics, 1914-1960, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 286-88.

[12] The United Nations was set up in San Francisco on 24 October 1945. The following Arab countries joined it from the beginning: Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Lebanon and Syria. When Serge drafted these lines, the UN had received Iraq’s adherence on 21 December 1945. Pakistan and Yemen became UN members on 30 September 1947. Turkey had joined right from the start.

[13] For a survey of the situation of the press in Arab countries between the mid-19th century and the mid-20th century, see Ami Ayalon, The Press in the Arab Middle East: A History, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 109-37.

Power, Politics, and Personification

Toward a Critique of Postone’s Theory of Antisemitism

This essay offers an immanent critique of Moishe Postone’s theory of antisemitism, arguably among the most influential such theory of the past forty years.[1] Postone’s entire oeuvre is dedicated to the proposition that power in capitalist societies does not reside with agents but in a system of abstract domination. He explains modern antisemitism as what happens when people do not recognize the abstract nature of that system and instead hold that there must be someone—the Jews—in charge of things, responsible for all they fear and suffer. This phenomenon he proposes we understand as a form of fetishised anticapitalism.

This piece is being made available as a preprint edition of the double-volume Marxism and the Critique of Antisemitism special issue of Historical Materialism. Further additions will still be made before then. The final published version of this text will be made available on the Brill website in the coming months. We ask that citations refer to the Brill edition.All Illustrations are by Natalia Podpora.

At the broadest level, what follows is simply an examination of what Postone means by each of the terms of his theory—modern, antisemitism, fetishised, anti-capitalism—and the implications of his particular understanding and uses of each. I contend that Postone’s theory rests on a complex, often ambiguous set of conceptual constructions. I begin with his definitions. While Postone sometimes distinguishes antisemitism among racisms, his theory rests on a categorical distinction of antisemitismfrom racism. This distinction, I suggest, makes it difficult for him to explain satisfactorily the political structure of right-wing and particularly National Socialist antisemitism. Instead, Postone focuses on the historical-epistemological: he wants to say that antisemitism is a matter of how some people think about and explain the world, but more, it is a matter of how the worldappears to them. The second part of this essay examines how he tries to make that case. Postone appeals directly to ‘Marx’s concept of the fetish’[2] but his own version of the fetish differs significantly from Marx’s. I suggest that the changes he rings on fetishism bring his conception of it closer to the structure of projection. This prepares the ground for the analogies Postone draws between the antisemitic image of Jewish power and the ‘abstract dimension of the value form’. But Postone needs more than an analogy. His observation that the Jews personify certain aspects of capitalist modernity is compelling, but he cannot convincingly explain personification as the direct result of how capitalism appears. For that he needs a different mode of explanation and a different conceptual apparatus.

I then turn to the thread that runs through practically all Postone’s writing on antisemitism. Postone develops his theory from an account of what he calls the ‘qualitative specificity’ of modern antisemitism, which is in turn derived from the singular features of the Nazi extermination of Europe’s Jews (extermination is in turn distinguished from mass murder and genocide).[3] Having staked so much on specificity Postone nevertheless argues that in the postwar period the same fetishised misrecognition and ‘pattern’ of thought is directed by left-wing ‘neo-anti-imperialism’ at quite different kinds of object—the US, Israel, and Zionism.[4] I argue that Postone’s own strictness about definitions mean he cannot collapse ‘neo-anti-imperialism’ into National Socialism, and show that Postone’s most rigorous formulations acknowledge key distinctions between modern antisemitism proper and its purported descendants.

In the final part of the essay, I argue that Postone’s notion of anti-capitalism contains a crucial ambiguity: sometimes it refers to explicit, conscious opposition to certain aspects of capitalism, which are mistakenly taken for all of capitalism; sometimes it refers to an implicit,unconscious opposition to all of capitalismand its social, political, and historical consequences. This becomes most evident when we consider one of Postone’s key claims: that his theory marks an advance on previous theories of antisemitism because his alone explains how the Jews were seen as the power behind both capitalism and communism. Pivotal in his framing of the question, communism disappears from his answer—and along with it, a fuller account of the political dimensions of modern antisemitism.Had Postone paid more attention to the distinction between the two forms of anti-capitalism, he would, I suggest, have found himself compelled to give a richer theoretical account of the place of abstraction in the distinctively political subjectivity and threat that obsess the right-wing variant of modern antisemitism. That task might, in turn, have drawn his attention toward contemporary Islamophobia, rather than (or as well as) criticism of the US, as significantly redolent of—while far from identical with—crucial aspects of the modern antisemitic imaginary.

The most obvious reason to grapple with Postone now lies in the profoundly fraught place of antisemitism in the contemporary political climate. On the one hand, there are myriad indications of antisemitism’s resurgence. Think, to take only the most obvious examples, of the spread of the fantasy of the Great Replacement, invoked by a distressing number of perpetrators of mass shootings as well as the white supremacists who rallied in Charlottesville in August 2017; the January 6, 2021 rioters’ displays of neo-Nazi symbols and antisemitic slogans; statistics suggesting a significant rise in antisemitic incidents; and the emergence of the QAnon conspiracy theory. Such events and phenomena make Postone’s observation that modern antisemitism ‘becomes virulent during structural, political, and cultural crisis’ seem all too timely, the search for answers all the more pressing.[5]

On the other hand, the very definition and extension of the concept of antisemitism has become a site of intense political contestation. Legal and cultural conflicts over the IHRA and BDS are only the most pointed instances of a broader and hardly symmetrical struggle over criticism of the state of Israel. It is in this respect that a certain reading of Postone has been incontestably influential on the German left, particularly for the Anti-Germans. Recent German laws and cultural controversies indicate that the views of the Anti-Germans have attained a certain cultural and political hegemony in the very nation their name claims to denounce.

My engagement with Postone seeks to clarify and parse the terms of the explanation he offers for why and how antisemitism emerges, and to respond to certain widespread interpretations and uses of his ideas. These goals distinguish my approach from other recent criticism of Postone. Both Karl Reitter and Michael Sommer take Postone to task for his use of the conceptual opposition of the abstract and concrete, and both are scathing on what they think Postone gets wrong about Marx and about German antisemitism. These are powerful, often convincing essays that share some points of overlap with mine (for example, Sommer too is struck by Postone’s use of analogy). They remain, however, largely external and polemical. One can imagine them leaving Postone unmoved since in Time, Labor, and Social Domination he provides, as it were, his own Marx, reinterpreted and critically reconstructed. Asking if his theory can satisfy its own criteria might provide both a sterner test and a more useful one, offering not only a critique but also a possible reconstruction of Postone himself. I continue to find some of Postone’s questions and observations about the structure of the modern antisemitic imaginary worth serious consideration. What I wrestle with here is how he arrives at his answers.

Definitions

Postone assumes that if you want to understand the singular fate of Europe’s Jews you need to examine the distinctive features of the kind of prejudice directed toward them and derive your explanation from those features. Having identified the key distinguishing features of antisemitism, antisemitism then becomes, for the purposes of Postone’s theory and for many who follow him, exclusively identified with those distinguishing features. But the distinguishing features are not necessarily the only relevant features. Focusing exclusively on distinguishing features not only has unintended ideological consequences but weakens both the historical explanation of antisemitism and our ability to understand how it might manifest in the present.

Postone sets out to capture what he called modern antisemitism’s ‘qualitative specificity’, a specificity that is manifest in turn in the historical distinctiveness of the Nazi extermination of the Jews.[6] He locates the distinctiveness of antisemitism in the ‘degree’ and ‘quality of power attributed to the Jews’. Where the power attributed to racial others is, for Postone, ‘usually concrete—material or sexual—the power of the oppressed (as repressed) of the “Untermenschen”’ the power attributed to the Jews by modern antisemitism is ‘mysteriously intangible, abstract and universal;[7] and where all other powers attributed to racial others is potential, Jewish power is believed to be real and dangerous.[8] Moreover, according to Postone:

This power does not usually appear as such, but must find a concrete vessel, a carrier, a mode of expression. Because this power is not bound concretely, is not “rooted,” it is of staggering intensity and is extremely difficult to check. It stands behind phenomena, but is not identical with them. Its source is therefore hidden—conspiratorial. The Jews represent an immensely powerful, intangible, international conspiracy.[9]

Postone rests his theory on a crucial analogy: the properties of the power attributed to the Jews—abstractness, intangibility, universality, mobility, not appearing directly but finding a concrete carrier— are, he says, ‘all [also] characteristics of the value dimension of the social forms analyzed by Marx’.[10] Postone argues that for the modern antisemitic imagination the Jews personify ‘the intangible, destructive, immensely powerful international domination of capital [as a social form].[11] Modern antisemitism needs to be understood as a ‘particularly pernicious fetish form’ that ‘becomes virulent during structural, political, and cultural crisis’.[12] It ‘revolts against history as constituted by capitalism, misrecognized as a Jewish conspiracy’.[13] This is the core of Postone’s theory, which does not seem to change significantly over time. Postone’s later writings will, however, make much of two further, related claims: first, that as a revolt against capitalism, antisemitism can appear ‘antihegemonic and anti-global’ and ‘hence emancipatory’[14]; second, that the Jews are seen as opposed to all of human existence. Postone refers to ‘modern anti-Semitism’s central element—the idea of the Jews as a world historical threat to life’.[15] He observes that ‘[a]ntisemitism then, does not treat the Jews as members of a racially inferior group who should be kept in their place (violently if necessary) but as constituting an evil destructive power – an antirace opposed to humanity. Within this Manichean worldview the struggle against the Jews is a struggle for human emancipation. Freeing the world involves freeing it from the Jews. Extermination (which should not be conflated with mass murder) is a logical consequence of this Weltanschauung’.[16]

Postone’s notion of particularly modern antisemitism rests on a claim about both its historical singularity—something new breaks through in the Nazi extermination—and its historical continuity, since modern antisemitism’s ‘emergence presupposed’ and shares the distinctive features oflongue durée antisemitism.[17] The examples Postone gives of the distinctive ‘degree of power attributed to the Jews’ are worth closer attention. He lists: ‘to kill God, unleash the Bubonic Plague, and, more recently, introduce capitalism and socialism’.[18] One of these things is not like the others. In the first two the Jews do not simply possess a particular kind of power but use it to kill, first the Christian divinity, then the Christian community. ‘Introducing’ capitalism and socialism is not of the same order unless it too is perceived as a mortal threat to some form of life.

In other words, I think Postone under-interprets his historical examples. Their common features become more conspicuous if you consider the list’s most surprising omission: the blood libel. The blood libel refers to the fantasy, originating in Western Europe in the thirteenth century, that Jews murdered Christian children and used their blood to make unleavened bread for Passover. The historian Gavin Langmuir argues that by virtue of itshostile attribution to Jews of unreal characteristics and actions that no one has ever observed, the blood libel marks the historical origin of antisemitism proper, as opposed to anti-Jewish prejudice.[19] In the fantasy of the blood libel, the Jews, perhaps unusually, do not necessarily possess any more power than anyone else, but use what capacities they do have to carry out acts that reveal a dedication to inhuman laws, rituals, and practices that present a mortal threat to the security and reproduction of the Christian community. This makes clearer what Postone’s other examples oflongue durée antisemitism already show: that antisemitism is not just a theory of how much power the Jews have, but always also a theory of what the Jewsdo, what those actions reveal about who they are, and why action must be taken against them.

Let’s also note, in passing, that the form this threat takes is not arbitrary, but bears a significant relationship to both Jewish and Christian religious practice. As Langmuir points out, the blood libel transforms the rituals of Passover into an inverted form of the Eucharist. It develops, he says, at precisely the moment the Christian Church in Western Europe is debating the ontological status of the Eucharist: are Christians consuming the real body and blood of Christ? The blood libel, for Langmuir, displaces and resolves these questions for the source community, by imagining that even the Jews, who officially do not recognise Christ’s resurrection, show through their actions that they ultimately believe in it. It takes something real—the Passover Seder—and uses it as a surface on which a fantasy solution to problems and anxieties specific to the Christian community’s own, related practice can be made ‘visible’.