Cathy Porter, author and translator, educated at London’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies and Cambridge University, has published over twenty books on Russian history, culture and politics, most recently Larisa Reisner. A Biography (2nd ed., Brill/Historical Materialism/Haymarket, 2022), shortlisted for the Isaac Deutscher Memorial Prize, and its accompanying volume Writings of Larisa Reisner, her six books, translated with Richard Chappell, again for the Historical Materialism Book Series. Author of Alexandra Kollontai. A Biography, first published in 1978, she is also a translator of Kollontai’s fictional trilogies Love of Worker Bees and A Great Love. This interview was originally published in About Narration (1975): Materials, Comments, Interventions, Edited and introduced by Sezgin Boynik and Tom Holert, Rab-Rab Press, 2025

The first edition of Larisa Reisner’s biography was published in 1988 by Virago. Why then?

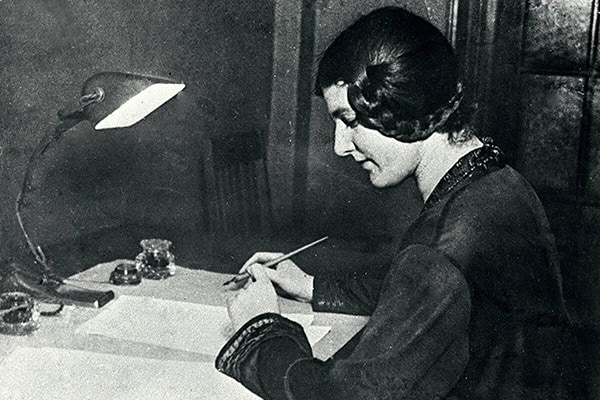

My interest in Larisa was first sparked by my work in the 1970s on Alexandra Kollontai, whose writings from the front lines of the Russian Revolution on workers’ power and women’s liberation were required reading then for the socialist movement. Working on Kollontai’s biography and translating the two volumes of her fiction made me want to know more about the generation of women who followed her and the legendary Larisa—“bursting across the revolutionary sky like a blazing meteor, dazzling all in her path”, wrote her comrade Trotsky. “She combined the soul of a warrior with the soul of a poet”, her lover Karl Radek wrote in his Preface to her Collected Works, published in 1928, two years after her death, at the age of thirty-one.

Discovering her short, extraordinary life, studying her writings, diaries, and letters has been an inspiring experience. Born in 1895 into tsarist Russia’s highly educated aristocratic elite, three decades after the emancipation of the serfs, when revolutionaries were just a tiny illegal underground sect, she lived through the last days of feudal serf Russia, the birth of capitalist Russia, the toppling of the Tsar, the great gulfs of World War, three revolutions, Bolshevik power, and the deadly Civil War that followed, when the massed armies of the capitalist world invaded Russia to bring down the Bolsheviks. Her books tell the story of her life in the Revolution, and they were the main source material for the biography, and her bold, inimitable voice makes her a powerful presence in them, although she virtually writes herself out of them, which is a rare and wonderful thing in this self-obsessed age. But she was remembered at different times in her life by many others, including some of the Revolution’s greatest fighters and writers.

The story goes that, on the night of October 25, when the Bolsheviks took power, she sailed with the sailors on the Battleship Aurora to the Winter Palace, where the Provisional Government was in session, and it was she who ordered the blank cannon to be fired at the Palace, signalling the birth of the new Russia and the Bolshevik government.

After October, she worked in red Petrograd at the Commissariats of Education and Trotsky’s new Red Navy, one of less than a dozen of the capital’s intellectuals who worked with the Bolsheviks in those early days. Then, the following summer, she left for the front line of the Civil War to defend the Revolution against the invading armies of the West and their White Guard allies. For the next two and a half years, she sailed on the warships of the new Volga naval flotilla as commissar, reconnaissance officer, cavalry commander, and journalist, fighting alongside the sailors in battles with the invaders and the Whites, from the Urals to Persia. And in moments snatched from the fighting, she wrote her “Letters from the Front”, reporting on the campaign, the horrors and heroism, the retreats and defeats, and the final victory.

After the Civil War, she lived for two years in Afghanistan as a member of the first Soviet diplomatic mission to Kabul, one of the first “red ambassadors”, representing Soviet power abroad. Historically, the key to the “Great Game” between the tsarist and British empires in Asia, Afghanistan, was now at the centre of the Bolsheviks’ complicated relations with British imperial power in Asia, and her instructions from the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs were to use the diplomatic and espionage skills she had learnt at the front to glean information about British activities and to gain access to the Emir’s all-powerful wife and mother in his harem, and persuading them and their entourages of the Bolsheviks’ friendly intentions in Afghanistan. All this was the material of her Comintern reports and her articles for the Soviet press, a dazzling mosaic of the sounds and colours of the East, full of sharp observations about Afghan life and the lives of Afghan women, and Soviet-Afghan-British relations.

In 1923, when Germany was swept with strikes that seemed to be taking the country close to revolution, she worked underground for the Comintern in Berlin, keeping the agents there in touch with each other and with those in Dresden and Hamburg. She was also publishing articles in the Russian and German press (she was bilingual in both languages) on German workers’ lives and struggles, the rise of the new doctrine of fascism and the communist-led fightback, Hitler’s “beer-hall putsch”, and the communist-led heroic workers’ uprising in Hamburg.

In 1924, she travelled as a journalist to the industrial Urals and the Donbas region of Eastern Soviet Ukraine, the heartlands of the new Soviet economy, reporting on workers’ lives in the mines and factories in the wake of the Civil War. The following year, she returned as a journalist to Germany, under the new president of the Weimar Republic, former Chief of the Imperial General Staff Field Marshal von Hindenburg, who, eight years later, would appoint Hitler Chancellor—“reporting from Germany’s streets, who was strolling, begging, starving, or motoring on them, from the power centres of German public opinion, the industrial workshops of the German spirit, German aesthetics, and German guns”.

She turned her journalism—from Russia, Ukraine, Germany, Persia, and Afghanistan—into her books The Front; Afghanistan; Berlin, October 1923; Hamburg at the Barricades; Coal Iron and Living People; and In Hindenburg’s Country. Non-Russian readers in the UK first discovered her writings in Richard Chappell’s translations of her German works, first published in 1977, now used in The Writings of Larisa Reisner, her six books, published together by Historical Materialism for the first time in translation, as the biography’s companion volume. Recently published in my translations is Rab-Rab’s beautiful edition of Reisner’s final masterpiece, portraits of Russia’s first revolutionaries, the Decembrists.

Three years after the first edition of the biography was published in 1988, the Soviet Union collapsed, and it was in a new Russia when I started work on the second revised edition. New material had been released since then from Larisa Reisner’s (now largely digitized) archives in the Lenin Library, with more of her diaries and letters published, more interviews with surviving friends, family members, and rehabilitated comrades, details of her student love affair with the executed poet Nikolai Gumilyov, restored Trotsky material censored from her 1958 and 1965 Selected Works, and her correspondence with Trotsky from Kabul in the 1920s. All of which makes this extensively rewritten, greatly expanded second edition, in effect, a completely different book. But her revolutionary message still rings out loud and clear for us now as it did then. She tells us how people made the first revolution in the world against capitalism, about the forces they were up against, and that they could be beaten. What we’re seeing now in the world truly looks like the beginnings of something similar: a genuine mass movement against the criminals in power, with millions on the march against Israel’s genocidal slaughter of the Palestinian people and its horrific repercussions and implications, and what better time than now to be rediscovering her life and writings.

What about her literary style?

She was widely considered to be the greatest journalist of the Revolution, read by millions in the new mass-circulation Soviet press, intellectuals, workers, and the newly literate. She wrote as a Marxist, led by the same principles that guided the Revolution, for a mass resistance movement against capitalism, built from below and rooted in the class struggle. And she wrote, as a poet, of epic struggles to make a new Russia to inspire the world.

Journalists of the Revolution had to be fighters for the Revolution—literally in the case of her “Letters from the Front”—writing under fire, taking on the forces of world reaction and counterrevolution, finding a new language for the world-shattering events of 1917 that would speak to readers and convey the mass dynamics of the struggle, connected to the masses through her vast cast of characters, all of them unforgettable, telling their stories and bringing them to life. It was a new kind of political journalism, agitprop and literary, bursting with energy, colour, and imagination, full of drama and poetry and Leninist class analysis, big ideas, and the everyday details of workers’ lives, with her dazzling shifts of mood between lyrical joy, tragedy, and comedy, endlessly wickedly funny and satirical in all sorts of cleverly subversive and unexpected ways, with her sharp eye for the fraudulent and bogus and the absurd, and all forms of male chauvinism and arrogance. And at the heart of all her writings is her unshakeable faith in workers’ creativity and solidarity.

The key to her literary style before and after the Revolution was her educational work. Centuries of tsarism left over 70 per cent of adult Russians illiterate, and after the March 1917 revolution, she joined the educational programme of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, teaching literacy in workers’ clubs in the capital’s poor suburbs, running literature classes for sailors at the naval garrison of “red Kronstadt”, the stronghold of Bolshevik power, and publishing articles in the socialist press about the new proletarian culture—“the creative pulse of the revolution, which is making culture the property of the people, the true inheritors of the treasures of the past”. On coming to power, the Bolsheviks declared their intention to make the entire population literate in their native language by the year 1923, and she joined the campaign to spread culture and education in the midst of war, poverty, and mass illiteracy, creating the new proletarian intelligentsia of the Revolution. In her work for the Commissariat of Education after October, she was appointed to the editorial board of the new State Publishing House, preparing cheap paperback editions of the foreign and Russian classics for mass publication. During the Civil War, teaching was a big part of her commissar’s duties at the front, working in lulls in the battles with teams of literacy teachers touring the battlefronts on agit-trains with posters, printing presses, and reading material, and sailors recalled crowding onto the ships for her frontline lectures on the songs and poetry of the Revolution. After the Civil War, she taught at the new workers’ colleges, preparing them to enter the universities, the rabfaks. The only qualifications required at the rabfaks were to be proletarian and literate, and she dedicated The Front to her students—“our future statesmen, scientists, judges, and professors, hungry for knowledge, working by day, studying at night, selling their last pair of shoes to buy the works of Lenin and Marx, who in a few short years must not only assimilate the old culture but shape its most valuable features into new ideological forms”.

A figure of great stature in the Bolshevik Party and staff writer for Izvestiya, the official daily newspaper of the Supreme Soviet, she was a “party-writer”, guiding readers to socialism, encouraging comradeship, collectivism, and the party-spirit, but never a party-proselytiser. She believed the new journalists should stay as close as possible to the lives of those making the new society and report truthfully what they saw, with a minimum of political commentary, “without varnish or adornment”, and she derided the “soul-daubers, who dip their brushes in buckets of cheap idealism and seek to sweeten the truth”.

She was a consummate stylist and a perfectionist, and, needless to say, impossible to translate, involving much slow, close reading of her works, constantly learning from them, and discovering new insights into our world today. Ingemo Engstrom and Harun Farocki tell the story of her life in Weimar Germany through his riot of interconnecting images, interviews, poems, and fairy tales, which match the riotous impressionistic language of her writings from the ruins of Germany’s “lost revolution”, a decade before Hitler—her warnings from history about the rise of fascism, which resonate powerfully with us now, with fascism putting down roots again in Germany, occupying more and more of the political space in the world.

Written in just under ten years, her books are simultaneously works of art, unique records of their time and place, guides to action, and sources of knowledge and information. We learn from them about the workings of capitalism and its fascist variant, the criminal imperialist wars fought in our name, and how knowledge is power and gives us the strength to act.

Which are your favourite works?

We’re spoilt for choice—from her first masterpiece, The Front, to her swansong, The Decembrists. Blisteringly funny in Afghanistan about the British in Kabul, “with their white helmets and high and mighty manners and disdainful smiles, cutting their faces like the notches on their bullets, their staggering contempt for these people of an inferior race”, with her rousing final chapter, “Fascists in Asia”, in which she identified the origins of the new doctrine of fascism in the gangster politics of colonialism and Britain’s regime of plunder and aggression in India and its “protectorate” Afghanistan. Berlin, October 1923, and In Hindenburg’s Country, reporting from the wreckage of society that produced the Nazi pathology of race-extermination and world domination, showing how the ruling fake-socialist Social Democrats were conspiring with the mainstream press to normalise fascism, brainwashing people to “accept the unnatural as natural”. Her poem to working-class heroism and resistance, Hamburg at the Barricades, first published in German, the first Soviet work in the Nazi book burnings to be thrown into the flames, followed by the works of Lenin, Gorky, and Mayakovsky—“for pursuing under the guise of historical accuracy a completely different aim, of providing instructions to the German Communist Party for a class civil war”.

All her books are brilliant and beautiful and educate and inspire us, but the two I most enjoyed working on were Coal Iron and Living People and The Decembrists. Both are masterpieces of style, gripping and atmospheric, full of pathos and poetry, bringing these two periods of Russian history alive for us with her usual wit and bravado and vast casts of unforgettable characters.

She was the first journalist to report on this epoch in workers’ history, building the foundations of the new Soviet economy, and there’s an epic grandeur to the writing in Coal Iron and Living People. The Front was dedicated to her rabfak students. She was writing this for the first heroes and heroines of Soviet labour, building socialism with superhuman energy and optimism on the eve of the mass industrialisation of the five-year plans.

She stayed with workers’ families, as she had in Germany, joining them on their shifts, and wrote of their miracles of courage and endurance, throwing the capitalists out of the mines and factories, fighting to defend them against the foreign invaders and the Whites, returning from the Civil War fronts to defend the Revolution on the new labour front. And she saw the same privations and sacrifices as in the Civil War—“the same class solidarity, which nothing the capitalist world throws at them can shake”. She wrote of the broken machinery, the failure and suffering, and of “workers’ superhuman sacrifices, labouring to drag Soviet industry out of poverty”. Of the new socialist labour ethos, free of the capitalist management techniques of sanctions and layoffs, when “everything that was alive was fighting to defend the Revolution, bound together in voluntary ties of discipline, in a struggle that had seemed so hopeless at the outset”. And, seven years after October, she was reporting that industrial output had outstripped prewar levels. “Clearly, this is due not to any technical improvements but entirely to workers’ incredible heroism, fighting to save Russia from economic ruin.”

She was fascinated by the labour-process, the coal and iron, the machines, mines, and factories, and her journalist’s notebooks in her archives are filled with graphs and statistics about prices and profits—“you have to be able to count the kopecks in the government’s pockets, not just the stars in the sky”. But the Revolution’s greatest resource was its living people, and it’s her characters who make the book so riveting, toiling on their mighty machines in the factories, crawling along dripping airless tunnels in the mines, knee-deep in mud in the platinum swamps high in the Ural Mountains. These scenes are intercut with episodes from workers’ history, from the era of serfdom and the birth of capitalism to the revolutionary struggles of her lifetime, building a picture of their lives that is heroic and inspiring.

She was also writing of the terrible working conditions, particularly in factories employing mainly women—the empty shelves in the shops, the painful reality of the new health system, the dire housing situation, “which can only partly and with difficulty be explained by the present deficiencies in our state budget”. She reported on the mood of revolutionary optimism at the party-meetings she attended, and the workers’ “deeply political understanding of the current policies of the Workers’ Republic, whose ruling class is condemned to endure these cruel conditions until the workers’ state is established”. And, mixed with their hopes for the new society, she wrote, was their anger with the party-leadership for its scandalous neglect of their needs.

Coal Iron and Living People is both a celebration of workers’ heroic fight to defend the Revolution and a resolutely direct, warm-hearted denunciation of the human cost, the suffering, injustices, and neglect, and she captures both with her usual inexhaustible faith in their resourcefulness and resilience. “Workers’ struggles and sacrifices give them the right to make the widest criticisms,” she wrote, “and the sharper these criticisms are, the more clearly we will see the face of the new post-revolutionary Russia.”

Her four Decembrist essays, her last published works, were written in 1925, a year before her death, the centenary of the rising, when officers in Saint Petersburg marched their men on Senate Square, refusing to swear allegiance to the hated new Tsar Nicholas I, demanding a constitution, the end of the tsarist autocracy, and the emancipation of the serfs. Three hundred of the rebels and 1,000 of their supporters on the Square were gunned down by forces loyal to Nicholas; five of the rising’s leaders were publicly executed, and over two thousand were sentenced to hard labour for life in Siberia.

The essays were her first works of history, looking back on this turbulent period in Russia with a Marxist understanding of the past. Two were published posthumously, and she was known to be working on more before she died. Deeply researched, based on material locked in the tsarist archives and released only after the Revolution, full of drama, imagination, and empathy, about the aristocrats, poets, and officers Lenin called Russia’s first revolutionaries against the tsarist autocracy. In his extensive writings about them, Lenin analysed the class nature of the rising, as the emerging capitalist class swept away old feudal Russia, showing how the interests of this new class aligned with the Decembrists’ slogans for a constitution, against serfdom and the tsars, essential if capitalism was to consolidate its power in Russia and flourish. “Revolution ceased to be the business of a small circle of top aristocrats; the Third Estate was now making a decisive intervention”, Larisa wrote, and she dramatised these competing class interests in the clashes between her main protagonists, whose voices are all distinct and different drawn from their own writings—lordly serf-owning Prince Trubetskoy, the traitor, elected “dictator” of the rising and the new republican Russia, who failed to appear on the Square; the lowly Kakhovsky, the Decembrists’ pawn; the successful businessmen and capitalists; the romantic poet Kondraty Ryleev; and the wise Baron Steingel, their treasurer. “Merchants! Good God, they want to bring merchants into our society!” Trubetskoy says.

She brilliantly captures the Decembrists’ secret criminal brotherhood, bound by class and the fear of discovery, their oaths and initiations, the intensity of their friendships, their allegiances and betrayals, Kakhovsky’s legendary love for Ryleev, who ultimately betrays him, and their journey together to the gallows. The defeat of the rising was a tragedy, she wrote, but the plot was dead as soon as it was hatched. They had the backing of an entire regiment and could have won, but the soldiers marching to the square were ordered not to appeal to the people on the streets to join them. “The young politicians understood society and its laws and feared above all a popular mass uprising, and this clouded their noble thoughts and deprived them of historical perspective.”

Much serious work on the Decembrists has been published in Russia in the build-up to the 2025 bicentenary of the rising, along with the inevitable trash—the massively popular 2019 blockbuster Union of Salvation, available on Netflix, derided by historians and critics as a “crime against history”, a “computer-generated action movie”, and “propaganda against any progressive movement against tyranny”, as well as the lunatic ravings of the far Right, tracing the criminal origins of the rising to the all-powerful Judeo-Masonic communist world conspiracy against Holy Russia, the tsars, and the Russian Orthodox Church. Larisa takes us back to this underground political counterculture and makes her amazing colourful characters alive for us with their dreams, dramas, and betrayals—a unique record in her inimitable style of this period of Russian history between feudalism and capitalism, before Marx and Lenin, connecting the Decembrists’ doomed heroic battle against tsarist cruelty and injustice with the revolutionary struggles of her lifetime. “Before 1825, the revolution was standing still, then it took to the streets and rushed”, wrote Viktor Shklovsky, who thought her Steingel piece was the best thing she ever wrote.

What was Reisner’s attitude towards the “Woman Question”, her relationship with Kollontai, and the Party’s Women’s Department, the Zhenotdel?

Kollontai’s writings on the sexual revolution and her work mobilising factory workers to the Bolsheviks made her a heroine for the generation of women activists who followed her, the liberated “new women” of the Revolution. Larisa was a role model for them and a trailblazer, a charismatic leader of women like Kollontai who identified with them and spoke for them, and they are some of her writings’ most powerful and interesting characters. But, unlike Kollontai (who explicitly rejected the anti-Marxist non-class politics of the feminists and any attempt to label her as one), she was never involved in the women’s liberation movement in Russia. She believed, like Rosa Luxemburg, that the best way for them to take their place in the revolutionary reorganisation of power was to put aside their differences with men and work with them as their equals, fighting shoulder to shoulder with them in the common struggle, defending themselves with their fists when necessary. She lived mainly in a male world, and her closest friendships were with men. “Larisa had no time for women who sighed into their pillows, complaining of their helplessness”, wrote her mother’s friend, the writer Nadezhda Mandelstam. “With her and her circle, it was the cult of strength. ‘We must create a completely new kind of Russian woman’, she said. ‘The French Revolution created its type, and we must do the same.’”

When women stormed to the head of the March 1917 revolution, they were already such a powerful force in the Party that Kollontai proposed establishing Party Women’s Sections to report back to the leadership on their needs. A majority of women party-members, however, rejected the idea as politically divisive, and Larisa probably agreed with them. The Party’s first woman political commissar after October, the only high-ranking woman commander in the new Red Fleet, she took for granted the new opportunities opening up for them in the Revolution, the new laws on their economic and sexual equality won for them by Kollontai and her generation of campaigners—introducing equal pay and proper maternity protection, razing to the ground the church-sanctioned tsarist marriage law, under which they were little better than slaves, classifying domestic abuse as a “counterrevolutionary offence”, punishable by jail, the first country in the world to legalise abortion. Trotsky and Victor Serge and her sailor comrades in the Civil War paid tribute to her great courage in battle, her steely confidence in the hard-drinking barracks world of the front, her struggles to be listened to and respected by sailors reluctant to accept the authority of the new commissars, let alone a woman, frequently having to defend herself against “discussions of the marriage question”. There’s nothing of this in The Front, but it was in her frontline journalism that she honed her formidable talent for skewering male power games and egos.

Her first recorded encounters with Kollontai were in the first days of the March Revolution at Kronstadt, where Kollontai was delivering the Bolsheviks’ message of revolution and women’s liberation, peace, bread, and land, at mass sailors’ meetings on board the battleships. As party-comrades, their lives intersected over the following years at key moments in the struggle, and although never involved in Zhenotdel policymaking, Larisa’s party-work connected with some of the huge range of its activities under Kollontai’s directorship—organising delegates’ assemblies in the factories and villages to fight sexual exploitation, working with the different commissariats on issues concerning women’s health and working conditions, supervising the publication of eighteen women’s magazines and newspapers, establishing a commission to help prostitutes access jobs, childcare, and secure accommodation, developing an impressive educational programme for women in the new Soviet Asian republics.

In 1920, in the Bolshevik-held Muslim city of Astrakhan, she worked with a dynamic team of Moscow Zhenotdel activists campaigning with local women against polygamy, child marriage, and the veil, setting up a new women’s club, clinic, and library. A year later, she spoke at International Women’s Day rallies organised by local Zhenotdel activists in the Black Sea resort of Sochi. In 1922, she corresponded with Kollontai from Afghanistan, sending her essays “Learning in the Harem” and “The Covered Woman and Her Child”, which evidently were not as appreciated by her male comrades in Kabul as they should have been: “the only person who might be interested in my sketches of Afghan women’s lives is you”. In 1924, she reported from a packed meeting in Soviet Ukraine held to discuss the new sexual morality of the Revolution and the new Soviet family life, one of thousands organized across the Soviet Union by the Zhenotdel and the Party to debate the terms of the new Soviet Family Code, passed in 1926, and she closely followed Kollontai’s contributions to the debate.

And, as with the first edition of my Larisa Reisner biography, the groundwork for this new one and the new translations was laid with the publication of more Kollontai—the updated edition of her biography (2014) and Alexandra Kollontai: Writings from the Struggle (2020)—thirty-two newly translated pieces with connecting commentaries, from her first years in the revolutionary underground in the 1890s to her work after October with the first Bolshevik government.

Reisner wasn’t part of the Workers’ Opposition or any other Opposition. Was she a fellow traveller?

She fought under Trotsky’s command in the Civil War, and they remained lifelong comrades, but she doesn’t belong in the Trotskyist box, as some now might wish. She abstained from voting for his anti-Lenin platform in the crucial 1920 party-debates on the trade unions, and there is no evidence she was involved with his Left Opposition—or with Kollontai’s Workers’ Opposition. She was a loyal party-member until her death. Trotsky coined the term fellow travellers for writers who were sympathetic to the Bolsheviks but not party-members, and like the fellow travellers, she exposed the gaps between slogans and reality in her writings. But she saw this as part of doing proper, truthful journalism, essential if the Revolution was to survive.

Nor does her writing fit into any of the other literary genres and alignments of the Revolution: the workers and intellectuals of the government-backed Proletkult, who claimed to be the “leading cultural organisation of the proletariat” on a level with the Party and who saw the new proletarian culture as a “vehicle for building the socialist society, in the spirit of comradely collective labour”; Shklovsky and the formalists, and their concept of “defamiliarisation”—although Shklovsky was a great admirer of her work; Mayakovsky and the LEF [Left Front of the Arts] Futurists, and their avant-garde allies in Europe. She wrote warmly before and after the Revolution of Mayakovsky’s poetry, his “rage, his love, his hunger for life and freedom”. But the futurists never had any detectable influence on her writing. She was perhaps closest in spirit to the poets and novelists of the socialist-realist school and the “industrial” writers of the post-Civil War reconstruction. Not the degraded barracks socialist realism of the Stalin era, but as defined by the father of Soviet literature, Maxim Gorky, and by Civil War novelist Alexander Fadeev, whereby “ideas should be conveyed through their living bearers, in their mutual relations, in the flaws and contradictions of their characters, in their flesh and blood”.

What did the poet Osip Mandelstam mean when he said, “Larisa died just in time”?

Larisa wrote of the Revolution’s mighty achievements—lifting millions out of dire poverty, introducing free universal healthcare and education, equal pay for women and the eight-hour day, nationalizing property, abolishing the old tsarist ranks and titles, and the Jewish Pale. And she wrote of its mistakes and failures: the ways the Party was failing those who had fought for the Bolsheviks and brought them to power; the official incompetence, bureaucracy, and corruption. It was nuanced journalism, and nuance was not an option for writers in the 1930s. She died before the purges, show trials, and the criminalisation of dissent, when dozens of her comrades, fellow fighters, and writers (including Mandelstam) were shot or disappeared into the camps as “non-people”, and her principled, uncompromising journalism, her wild free spirit, and her closeness to Trotsky make it highly likely she would have shared their fate.

In her lifetime, her writings came under attack in Russia from hard-line defenders of proletarian purity, who saw her style as too fancy and “feminine” to reflect the reality of workers’ lives, claiming her aristocratic origins disqualified her from writing of the Revolution from the proper class perspective. Leading the attack was the proletarian poet Demyan Bedny, known as the “Poet Laureate” of the Revolution, who denounced The Front at a Moscow writers’ conference in 1925 as “tawdry, pretentious, and affected”. His true target, though, was surely Trotsky and The Front’s glowing praise for his military genius in the Civil War. A member of Stalin’s inner circle, one of his very few close personal friends, had a long correspondence with him about literature, politics, and the anti-Trotsky campaign, expressed in violently antisemitic language. And since he was speaking just two days after Trotsky was forced to resign as War Commissar, his first major defeat at Stalin’s hands, it seems likely Stalin was behind the speech as his opening shot against her in his ongoing campaign to destroy Trotsky. But, if so, it spectacularly misfired. The official Party paper Pravda mocked “Bedny’s belching communist arrogance”, and Izvestiya published dozens of letters from her admirers. “‘Pretentious and affected’—that scum Demyan knows nothing; he’s just jealous; Larisa Mikhailovna is a tiger!” wrote the Urals miner Vladimir Lavrov.

Bedny himself inexplicably fell out of favour with Stalin seven years later, and, in 1938, he was expelled from the Party and stripped of his Writers’ Union membership. Larisa became a “non-person” by association after she died, and her works were withdrawn from publication. The last chapter of the biography, “Afterlife”, tells the stories of some of her comrades who perished and were rehabilitated in the de-Stalinisation of Russia following his death, when her works began to appear in print again, starting in 1958 and 1965, with the publication of two carefully edited and annotated volumes of her Selected Works, with warmly sympathetic introductions and all references to Trotsky and other oppositionists removed.

What are the reasons behind the ongoing campaign to vilify her?

She writes of the cruelty and injustice of the capitalist system and shows us that a world free of capitalism is possible, and this makes her as dangerous now to the forces of reaction as she was in her lifetime. And perhaps it’s also partly because she evades easy definition politically, as a woman and as a writer, that it’s been so easy for the Big Lie school of pseudohistory to get its teeth into her.

Women who fought for the Revolution have always been favourite targets of its enemies abroad and of Russia’s “internal émigrés”, and she was slandered and pornographized, both in her lifetime and after her death, as a monster of depravity, barely human, who played sex games with her White Guard prisoners before torturing them to death, living in luxury, parading around in the furs and jewels of the murdered royal family while Russia starved.

The 2017 centenary of the Revolution was marked in capitalist Russia by the big-budget eight-part TV series Trotsky (available on Netflix), a grotesque concoction of historical falsifications, antisemitism, and porn, with a leather-clad fanatic Trotsky as the agent of a secret international Jewish cabal plotting world domination, and Larisa his chief accomplice and groupie, writhing and groaning with him on his military train as it speeds towards the battlefield at Sviyazhsk, where, in an orgy of sadism, they call one in ten sailors from the ranks to be shot.

Unfortunately, any discussion of her now has to be in the context of the ongoing campaign to poison her legacy. Following the publication of the first edition of the biography, there was a flurry of fact-free smear jobs by Western writers, trashing her character, her politics, and her writings, accusing her of sleeping with the party-leaders to advance her career as a journalist, a talentless hack, churning out Bolshevik propaganda for the masses. Last time I Googled her, prominently displayed twice, above details of this second edition, were links to the most defamatory, fact-free of the pieces, first published in a respectable US academic journal, insinuating absurdly but predictably that she was antisemitic. I’m told nothing can be done about Google Analytics.

The lies and hysteria about her are generated by the same propaganda machine that has branded the greatest journalist of our times, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, a “hostile intelligence force” for publishing his ten million brilliant world-changing leaked documents exposing capitalism’s dirty secrets and criminal imperialist wars. Silenced, tortured, and jailed in maximum-security Belmarsh Prison—Britain’s Guantanamo—and falsely accused of sex crimes by virtually the entire world media, effectively signing their own death warrants, which made campaigning against his extradition so desperately difficult, he was awaiting the final High Court ruling in July on his fourteen-year case, when he would learn if he was to be put on a plane in shackles to face the next stage of his unimaginable suffering in the United States, when the totally unexpected wonderful news came that he was to be released. It’s a huge victory. The CIA knew its case against him was weak and couldn’t risk failing. But his treatment has been a terrible warning to any journalist wanting to do proper, truthful journalism and to any of us who step politically out of line, and our fight for justice for him continues. Our campaign against his extradition revealed so many parallels with Larisa a century earlier: both frontline journalists, speaking the language of our present struggles against fascism, imperialist wars, and the genocidal slaughter of the Palestinians, both dangerous, censored, and similarly slandered as sexual perverts, because heaven forbid anyone should read a word they wrote or trust a sexual pervert.

The latest Larisa horror, published by Rowohlt Verlag in Germany, is best-selling multi-award-winning novelist Steffen Kopetzky’s much-hyped blockbuster bombshell revelations spy thriller Damenopfer, with its hideous, dead-eyed psycho Larisa on the cover, about her plot to take over the world with her soulmate and lover Nazi mystery man spy General Oskar von Niedermayer (known as the German T.E. Lawrence) and their “secret armaments project” in Moscow and Berlin—“which has played a central role in the mayhem and violence of the 20th century, and has had a direct impact on the murky fate of our planet to this day”. All complete nonsense, of course, intended to muddle us, horribly written, clearly dashed off in a rush to a deadline, full of clichés and anachronisms, ludicrous interactions and dialogue, casual sadism, and leering sexism. (The nature of the “armaments” is never revealed.)

We must just draw strength from her writings and the example of her life to defend her from the fake Larisas dreamed up by this alliance she identified in her German writings between the hard Right and the pretend Left, and be glad they can’t come up with anything better against her than the imposter Kopetzky and rehashed forty-year-old lies.