In April 2019, the Japanese Marxist economist Teinosuke Ōtani[1] died at the age of 84. Outside of Japan, Ōtani is probably best known for his involvement in the Marx Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA) project. From 1992 until his death, Ōtani was a member of the editorial board of the Internationale Marx-Engels-Stiftung (IMES), which is tasked with editing new MEGA volumes; and, from 1998 to 2001, he headed the Tokyo-based MEGA editing team.[2]

What is less known about Ōtani in the English-speaking world is his extensive research on the original manuscripts for Book II and III of Capital. For nearly 40 years, starting in the early 1980s, Ōtani carefully examined these manuscripts and compared their content to that of the published volumes of Capital edited by Friedrich Engels. His academic papers and partial translations of the manuscripts are collected in two works: Reading Marx’s Struggles in the Manuscripts of Capital (Ōtani 2018) and the four-volume Marx’s Theory of Interest-Bearing Capital (Ōtani 2016). The former centres on the manuscripts for Book II, while the latter deals with Book III (particularly Chapter 5). These two works examine in detail how the published volumes of Capital diverge from the original manuscripts as a result of Engels’s deletions, additions, and restructurings. Since few English works to date have presented Ōtani’s research on Marx’s manuscripts,[3] here I would like to offer an overview of it, with a focus on his interpretation of Marx’s theory of interest-bearing capital.

Ōtani’s “apprenticeship” under Samezo Kuruma

Teinosuke Ōtani belonged to the generation that came of age in the 1950s, when Marxism enjoyed enormous prestige among Japanese intellectuals. In the field of political economy, in particular, Marxists maintained an almost hegemonic position until the 1980s. However, this was also the generation whose “midlife-crisis years” overlapped with the crisis of confidence that overtook Marxism following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This historical turning point forced Ōtani to consider whether “really existing socialism” had ever really been socialist at all, leading him in the direction of a theory of state capitalism and a new understanding of socialism (or “Association” – to use his own preferred term).[4] Instead of moving away from Marx during this period of crisis, Ōtani delved deeper into his ideas on a future society and descriptions of how the material conditions necessary for develop within capitalism.[5]

Ōtani was better able to navigate this difficult period than some of his colleagues because his research had always been more centred on the ideas of Marx than the ideology of Marxism. His close reading of Marx’s texts was strongly influenced by the scholarly attitude of Samezō Kuruma (1893–1982), with whom he collaborated for many years. Kuruma was one of the pioneering Marxist economists who emerged in the 1920s. For most of his career, Kuruma worked as a researcher at the Ōhara Institute for Social Research (OISR), which he joined at the time of its establishment in 1919. Ōtani met Kuruma for the first time in 1957, soon after beginning a graduate program in political economy at Rikkyo University. The occasion was his participation in a study group on crisis held at Kuruma’s home in Kichijoji, in the west of Tokyo. Ōtani would visit the home regularly in the years that followed to meet Kuruma’s son Ken, who was enrolled in the same graduate programme and would later teach Marxian political economy at Rikkyo.

Around 40 years later, long after the death of Samezō Kuruma, I became a regular visitor to the house in Kichijoji myself. In 2004, I had contacted Ken Kuruma to express my interest in his father’s work and ask permission to translate some of it for the Marxist Internet Archive. Ken was also a Marxist economist and had written extensively on Marx’s theory of money and applied it to the analysis of inflation and the examination of the modern financial system.[6] When we came into contact he had just published a book aimed at the “general reader” titled Can Capitalism Survive: The Collapse of the Doctrine Prioritising Growth (Ōtsuki 2003), which deals with some of the issues that would be addressed in the work of Kohei Saito around a decade later.

A friendship soon developed between Kuruma-sensei and me, and, on Sunday afternoons, I would often stop by his house, which was only a short bike ride from where I lived at the time. Over green tea and traditional Japanese confectionaries we would talk about the translations that I was working on and the state of the world, and Kuruma-sensei would also share recollections about his father. Adjoining the living room where we talked was a library lined with dusty volumes his father had collected, including old issues of the OISR journal in which so many of his articles and translations had first been published.

It was through Kuruma-sensei that I came into contact with Ōtani-sensei – or “Theo”, as he asked me to address him on the day we met in that same living room in Kichijoji. At the time I met him, Professor Ōtani was the representative director of the Japan Society of Political Economy and was also editing MEGA II/11, containing manuscripts for Book II of Capital. He presented me with his recently issued textbook on the three volumes of Capital that was filled with original diagrams he created to illustrate important concepts, and, in the years that followed, I worked on and off on translating for my own study and in the hope of finding a publisher for it. More than a decade (and a global financial crisis) later, an English edition was finally published by Springer under the title A Guide to Marxian Political Economy (Ōtani 2018). Over that time, I was in frequent contact with Professor Ōtani in connection to this project and my translations of the works of Samezō Kuruma, and on a number of occasions visited his workspace (also a short bike ride away) to discuss those and other things over dinner and a few glasses of shōchū. This interaction revealed to the incredible energy and attention to detail that he brought to every task and how he was motivated by the belief that his work was contributing to a necessary social transformation.

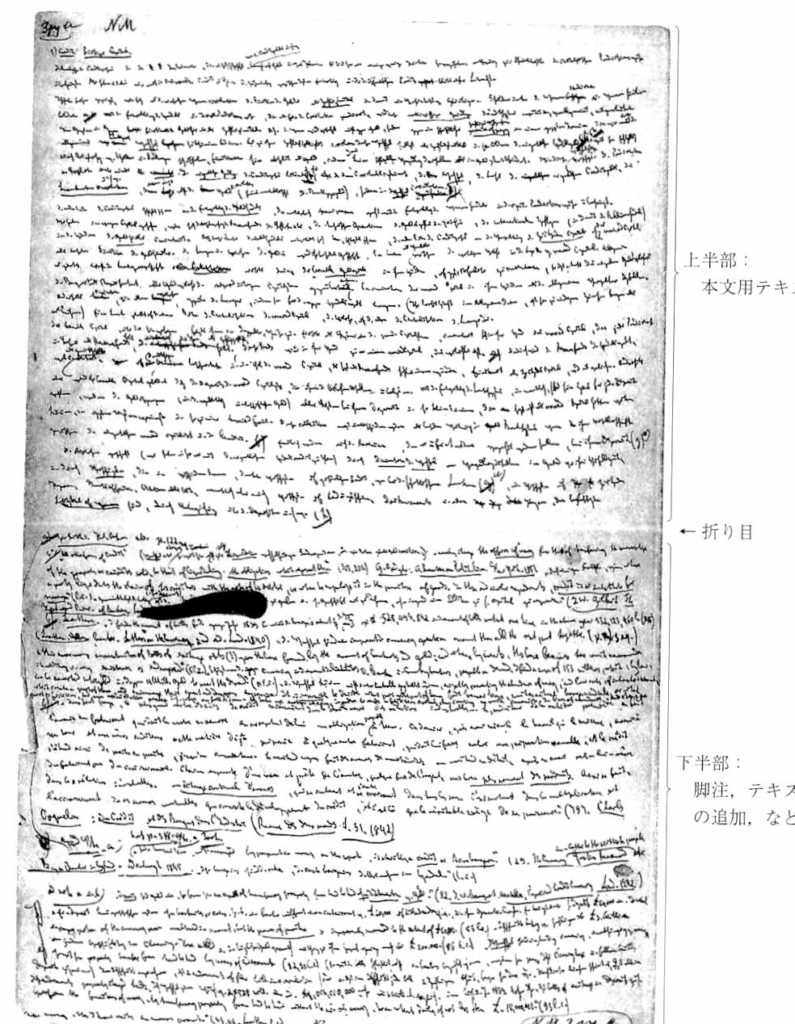

Ōtani first demonstrated his remarkable abilities as an editor, translator, and scholar through his participation in the editing of Samezō Kuruma’s Marx-Lexikon zur politischen Ökonomie (1968–1985). This project grew out of Kuruma’s enormous collection of notecards containing excerpts from the works of Marx and other writers. From the outset of his career, Kuruma had been in the habit of creating notecards to collect important citations and his own observations on whatever he was researching. In the 1920s and 1930s, most of his notecards concerned crisis, as he hoped to complete a book on the topic. Unfortunately, this first collection of notecards was lost when the OISR office in Tokyo was destroyed by an air raid in May 1945.

After the war, Kuruma steadily built up a new stack of notecards as his research progressed, this time covering a wider range of subjects. By the 1960s, the collection numbered around 10,000 notecards. In order for his colleagues and students to be able to more easily access this useful resource, Kuruma decided to catalogue the collection – or, rather, he asked his son to do it for him. Ken managed to put it off this onerous task until Ōtani stepped in to undertake it, demonstrating the energy and attention to detail that would make him such an outstanding MEGA editor a few decades later. By 1965, Ōtani had completed the job of putting Kuruma’s notecards into order.

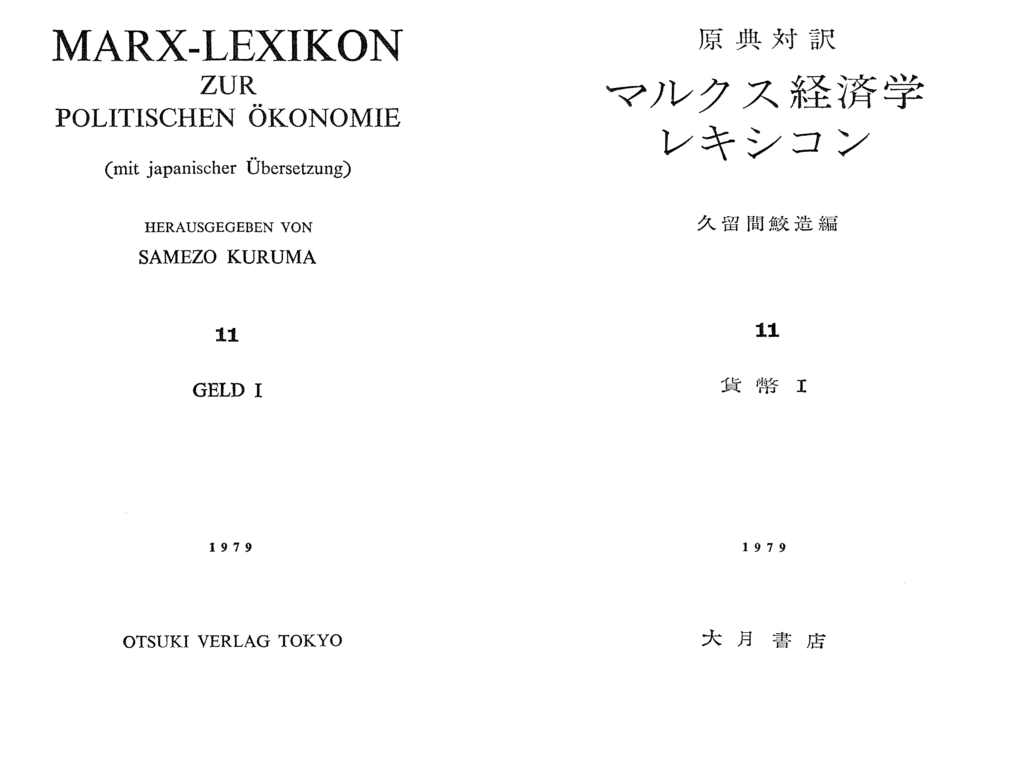

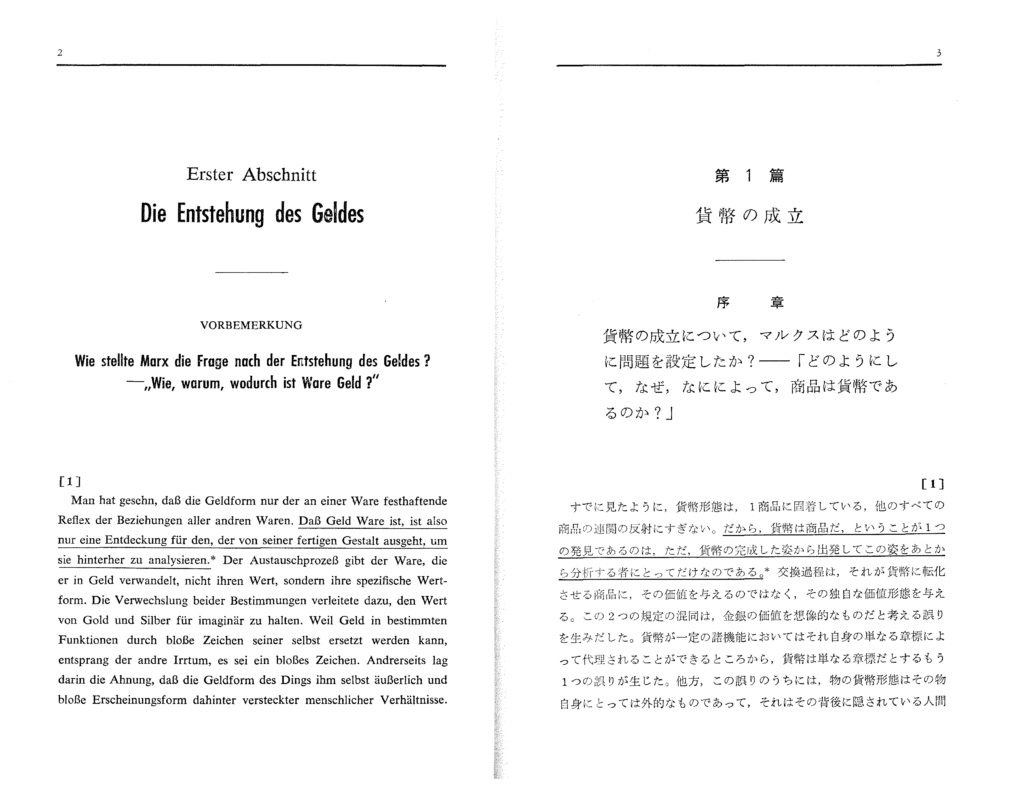

Soon after the collection was catalogued, its existence came to the attention of Naoe Kobayashi, an editor at Ōtsuki Shoten, which the publisher of the Japanese language edition of Marx-Engels-Werke. Kobayashi proposed publishing the content of the notecards in book form, and this eventually led Ōtsuki Shoten to partner with the OISR to back Kuruma’s Marx-Lexikon zur politischen Ökonomie (1968–1985) – a 15-volume collection of passages from the works the works of Marx on a number of key topics, with original German alongside the Japanese translations. The name Marx-Lexikon was modelled after the Hegel-Lexikon (Hermann Glöckner, ed.), while the format of arranging passages under various headings and subheadings was influenced by the Marx Brevier (Franz Diedrich, ed.) and the Friedrich Engels Brevier (Ernst Drahn, ed.). This format is quite different from a comprehensive dictionary of Marxist thought, such as the Dictionnaire critique du marxisme (Georges Labica, ed.) or the related Historisch-kritisches Wörterbuch des Marxismus (Wolfgang Fritz Haug, ed.). Instead of providing definitions of fundamental concepts, the scope of Marx-Lexikon is limited five key topics: competition, materialist conception of history, method, crisis, and money. Kuruma was particularly interested in topics that are not dealt with in a single place within the work of Marx and thus require taking his entire oeuvre into consideration. Another characteristic of Marx-Lexikon is that it aims to encourage readers to grapple with lengthy passages on their own, instead of providing conclusions or definitions. Kuruma wanted readers to go straight to the source and read Marx carefully for themselves, rather than relying on his own interpretation or synopsis.

Taking part in the Marx-Lexikon project was a formative experience for Ōtani. He later explained that Kuruma never tried to fit passages from Marx into a preconceived framework or set of categories. As an example, he described how Kuruma edited the four Marx-Lexikon volumes on crisis by first sorting through all of the notecards in which Marx referred to crisis or conducted an analysis related to crisis. Next, he carefully read the content of the cards and created headings to summarise the essential content. The headings were then used as a guide to bring together stacks of cards dealing with similar content. The list of headings for the Marx-Lexikon volumes on crisis thus emerged gradually through this process, rather than being dictated by preconceived notions. Ōtani saw this as an approach that offered readers the opportunity “to learn directly from Marx himself”.[7]

Ōtani thought that the virtues of Marx-Lexikon arose from Kuruma’s own characteristics as a scholar. He noted that Kuruma “never hurried to publish, nor did he dash off essays on every thought that occurred to him”. Moreover, he “never treated his own work as if it were his private property”, as was clear from the generous way he shared his enormous collection of notecards that took so many years to compile. Similarly, instead of “keeping his ideas locked away until the moment he could publish them”, he shared them freely with others. With this outlook, Kuruma “never bowed to any authority outside of scholarship” and “did not seek to become an authority outside of it”, and “never dreamed of gathering a circle of talented followers and distributing them among universities across the country to build up his own personal network”.[8]

In turn, Kuruma benefited tremendously from the participation of Ōtani in the Marx-Lexikon project. As already explained, the project would not have gotten off the ground in the first place without Ōtani’s cataloguing of the notecard collection, and, at every step that followed, he played an important role. Along with his contribution to the editing of each volume, Ōtani shaped the recorded discussions between the editors into a simplified – and at times semi-fictionalised – transcript that was inserted in each volume to clarify key issues addressed.[9] Ōtani also played an important role in helping Seijirō Usami revise existing Japanese translations of Marx’s writing to improve the level of accuracy.

Ōtani begins researching the manuscripts for Capital

During the period of editing the Marx-Lexikon, Ōtani gradually became aware that the original manuscripts for Book II and Book III of Capital diverge on some points from the published Volume II and Volume III. He first became aware of the divergence through the work of Kinzaburō Satō.[10] In 1970, Satō had spent two months at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam researching the manuscript for Book III of Capital. At the autumn conference of the Credit Theory Research Group held that same year, he reported on some of his findings and followed up on this with a three-part article for the journal Shisō. This research stimulated Ōtani’s desire to examine the original manuscripts, and an opportunity to do so came when he was awarded a sabbatical from Hosei University in 1980.

Ōtani spent the next year two years in Europe researching the manuscripts for Book II and Book III of Capital. After a six-month stay in Rothenburg ob der Tauber in West Germany, where he studied German intensively, Ōtani moved on to the Bad Godesberg district of Bonn and, over the next eight months, travelled weekly to Amsterdam to study the manuscripts for Capital at the IISH. Thanks to the intervention of the research fellow Goetz Lankau, Ōtani was able to examine the manuscript for Book III even though he was an unknown researcher who did not even have a letter of introduction. Next, Ōtani went to East Berlin, where he researched materials held by the Institute of Marxism-Leninism and befriended the researchers Hannes and Ingrid Skambraks. This was followed by a little over a month in Moscow to read and take notes on the deciphered transcription of Marx’s handwritten draft of Book III of Capital at the Institute of Marxism-Leninism there. Finally, Ōtani lived for three months in Wormerveer, about a 20-minute train ride from Amsterdam, and again researched various manuscripts for Capital at the IISH. Ōtani returned from his European sabbatical in 1982 with six notebooks containing his transcriptions of Chapter 5 of the manuscript for Book III of Capital and his related notes. This would serve as the basis for the research he would carry out over the next 20 years.[11]

Although Ōtani’s research would illuminate the differences between the original manuscripts and the published volumes of Capital, he never diminished the enormous accomplishment of Engels as the editor. Ōtani recognised the enormity of the task of “transforming extremely fragmentary and unfinished manuscripts into a coherent book”, describing the accomplishment as “masterful despite certain flaws or shortcomings”.[12] Had Engels not managed to publish Volume II and III, Ōtani points out, it is doubtful whether economists after Marx would have been able to independently develop such concepts as fixed and circulating capital, the reproduction and circulation of the total social capital, or the average rate of profit and production price.

At the same time, Ōtani points out that Engels gave readers a mistaken impression about the state of the manuscripts that he fashioned into completed volumes. With regard to the manuscript for Book III, in particular, one would assume from the published Volume III that the manuscript was almost complete, whereas, in fact, many parts have the character of being working notes for an ongoing investigation. Moreover, since the edition of Volume III edited by Engels makes references to Volume I and II, it seems to readers that the manuscripts were written sequentially whereas, in fact, a coherent draft of Book II did not yet exist when Marx began writing the manuscript for Book III. The impression of completion is reinforced by the comments of Engels in his preface to Volume III where he states that he had confined his editing “simply to what was most necessary” and that any significant “alterations or additions” of his own were placed in brackets and indicated with his initials;[13] whereas, in reality, there “numerous unnoted interventions…throughout the text” – and “by no means were all of them appropriate”.[14]

Engels was straightforward in recognising that the editing of Part 5 – or Chapter 5 in the original manuscript – presented him with a “major difficulty” because it was not a “finished draft, or even an outline plan to be filled in, but simply the beginning of an elaboration which petered out more than once in a disordered jumble of notes, comments, and extract material”. Initially, Engels tried to fill in the gaps and elaborate the fragments “so that it would at least contain, by and large, everything the author had intended to include”; however, after at least three failed attempts, he decided that this approach was “hopeless”, as it would have required extensive research and resulted in something that “was not Marx’s book”. This left Engels no alternative, according to his own account, but to confine himself “to arranging the material as best [he] could” and only making “the most necessary alterations”.[15] In fact, however, as Ōtani soon discovered in the course of his research, Engels made numerous revisions and deletions that altered the substance of Marx’s arguments.

Changes made by Engels to “Chapter 5” of the manuscript

Ōtani points to two broad circumstances that account for the divergence of the published volumes edited by Egnels from the original manuscripts. The first factor is that, in editing Volume III, Engels had Marx’s manuscript transcribed by a young typesetter named Oskar Eisengarten, who produced produce a “clean copy” that would be easier to read. Engels then proceeded to edit the manuscript based on this transcript. This may have accounted for some of the lapses in accuracy, according to Ōtani. The second factor is that Engels was largely unfamiliar with the content of Book III, apart from explanations received from Marx in a few letters. Ōtani argues that Engels may have formed a few misconceptions about Chapter 5 of the manuscript from these letters that ended up shaping the direction of his editorial work. In particular, Ōtani points to Marx’s reference in his letters to that chapter in his manuscript as the “chapter on credit”. In his own correspondence around the time he was editing Book III, Engels likewise refers to the corresponding Part 5 as the “sections on credit”.[16] For Ōtani, the mistaken belief that this part of the manuscript centres on banking and credit strongly influenced how Engels carried out his editing of Part 5 of Volume III. Engels’s interpretation of Chapter 5 of the original manuscript is reflected in his division of the material, as shown in Table 1.[17]

| Chapter 5 of Book III (Manuscript) | Part 5 of Volume III (Engels edition) |

| Title: The Division of Profit into Interest and Profit of Enterprise (Industrial or Commercial Profit). Interest-Bearing Capital | Title: The Division of Profit into Interest and Profit of Enterprise |

| 1) [untitled] | Chapter 21: Interest-Bearing Capital |

| 2) Division of Profit. Rate of Interest. Natural Rate of Interest | Ch. 22: Division of Profit. Rate of Interest. |

| 3) [untitled] | Ch. 23: Interest and Profit of Enterprise |

| 4) The Externalisation of Surplus-Value and the Capital Relation in General in the Form of Interest-Bearing Capital | Ch. 24: Interest-Bearing Capital as the Superficial Form of the Capital Relation |

| 5) Credit. Fictitious Capital | Ch. 25: Credit and Fictitious Capital

Ch. 26: Accumulation of Money Capital, and its Inflation on the Rate of Interest Ch. 27: The Role of Credit in Capitalist Production |

| I) [untitled] | Ch. 28: Means of Circulation and Capital. The Views of Tooke and Fullarton |

| II) [untitled] | Ch. 29: Banking Capital’s Component Parts |

| III) [untitled] | Ch. 30: Money Capital and Real Capital I

Ch. 31: Money Capital and Real Capital II Continuation) Ch. 32: Money Capital and Real Capital III (Conclusion) Ch. 33: The Means of Circulation under the Credit System Ch. 34: The Currency Principle and the English Bank Legislation of 1844 Ch. 35: Precious Metal and Rate of Exchange Ch. 36: Pre-Capitalist Relations |

| 6) Pre-bourgeois | Ch. 36: Pre-Capitalist Relations |

Engels divided the material into 16 separate chapters to form Part 5 of Volume III. Chapters 21 to 24 correspond quite closely to Sections 1) to 4) of the original manuscript, while Section 5 basically matches Chapter 36 in the edition of Engels. However, Section 5 alone is divided into 12 separate chapters. Ōtani points to two problems in particular concerning the way Engels arranges the material in these chapters.

First, the title of Section 5 is “Credit. Fictitious Capital”, but “fictitious capital” only appears in the title of Chapter 25, as if that were the only chapter dealing with this topic. Moreover, the part of the manuscript corresponding to that chapter, in fact, contains almost no discussion of fictitious capital. In order to make the material fit the chapter title, Engels inserted excepts from subsequent parts of the manuscript and also added two parenthetical remarks under his own initials. This creates the impression that the discussion of fictitious capital is concentrated within this chapter.

The second main problem is that Engels failed to distinguish between the main text of the manuscript and the parts that contain notes or reference materials. Marx had the habit of writing the main text on the upper half of the page, leaving the lower half blank as a space for footnotes or additions. There was no such division in two for pages on which he was compiling reference materials and additional notes. However, Engels treated Marx’s notes and other materials as if they were part of the main text. This was probably due to the fact that Engels was working from a transcribed text rather than the original manuscript. In adding notes taken from later portions of the manuscript to Chapter 26, Engels ended up breaking up the logical progression of Marx’s argument.

In addition to these overall structural differences between the original manuscript and the Engels edition of Volume III, Ōtani points to changes made by Engels to the text that influenced the interpretation of Chapter 5 of the manuscript. At the beginning of that chapter, for example, Marx writes that “The analysis of the credit system and of the instruments it creates for itself, such as credit money, lies outside the scope of our plan”.[18] Engels alters this sentence by changing “analysis” to “detailed analysis”, thus creating the impression that the examination of the credit system does, in fact, belong to Part V of Volume III – albeit not in a detailed form.

Other examples of revisions that were made by Engels to place credit at the centre of Part 5 of Volume III can be found. For instance, near the end of Chapter 27 in the Engels edition, there is the following: “In the following chapters, we will examine credit in relation to interest-bearing capital itself”.[19] However, in the original passage, Marx writes: “In what follows we shall move on to consider interest-bearing capital itself” after which is added, in brackets “both the impact of the credit system on it and the forms it assumes therein”.[20] In other words, Marx makes it clear in the manuscript that his analysis centres on “interest-bearing capital”, whereas, in the Engels edition, the emphasis is placed on “credit”. It has thus been assumed, based on the published Volume III, that Marx’s examination centres on the credit system from this point in Part 5 – and this seems to have been the assumption of Engels himself.

Ōtani’s interpretation of Chapter 5 of Book III

In his close reading of the original manuscript, Ōtani discovers a quite different development of Marx’s argument, which he divides into the following two broad categories, with the latter corresponding only to the final section (or Chapter 36 in the Engels edition):

- Theoretical development of interest-bearing capital

- Historical consideration of interest-bearing capital

Ōtani further divides the theoretical development of interest-bearing capital into the parts that provide a “conceptual grasp of interest-bearing capital” (corresponding to the first four sections in the manuscript) and the “examination of interest-bearing capital under the credit system” (corresponding to the fifth section). By “conceptual grasp”, Ōtani is referring to the effort to understand the essence of the phenomenon of interest-bearing capital and position it as a definite concept. This is the basis for then reproducing in thought the concrete form of interest-bearing capital, which Marx refers to as “monied capital” or “moneyed capital”. This monied capital operates within the credit or banking system, taking on concrete forms within that institutional framework.

(Before progressing further, a word should be said about the term “monied capital” and the distinction between it and “money capital”. Ōtani notes that economic actors in the 19th century themselves referred to the mass of money concentrated in banks, awaiting investment, as “monied capital”. In contrast, “money capital” – as used by Marx – refers to industrial or commercial capital in a monetary form, which is to say, one of the forms of capital in its circuit. Marx employs the term “monied capital”, in contrast, to denote the form in which the interest-bearing capital that operates within the credit and banking system appears in people’s consciousness. In his analysis of interest-bearing capital in Chapter 5 of the manuscript for Book III, Marx sets aside “money-dealing capital”, which is another type of capital that operates under the credit or banking system: this is capital involved with the handling of money, as a special type of commercial capital that earns profit from tasks related to circulation. Marx examines this form of capital in Chapter 4, where he analyses commercial capital.)

Chapter 5 of the manuscript for Book III begins by clarifying the essence of interest-bearing capital. In the first section, Marx explains that interest-bearing capital is a distinct form of capital that appears to economic participants as money bought and sold in the money market as a commodity, having the property of being potential capital. In this case, its “use-value” is the ability to yield an average profit. In fact, however, the interest that is the “price” of this commodity is just one portion of the surplus-value produced when money actually functions as productive capital in the production process.

The second section of Chapter 5 further clarifies that interest, as a portion of profit, can theoretically fluctuate anywhere between 0% and the average rate of profit, but does not have any intrinsic determination (unlike the case of profit itself). The rate of interest is instead determined by solely by competition, in terms of supply and demand with regard to interest-bearing capital in the money market.

With the existence of interest, money capitalists appropriate a portion of profit in that form, while the remainder goes to the industrial and commercial capitalists. These two portions, which stem from the same source, appear to be qualitatively distinct from each other – as if interest were the fruit of the ownership of capital, while what remains seems to be compensation for the functioning of capital, referred to by Marx as “profit of enterprise”. This is what Marx explains in the third section (corresponding to Chapter 23 in the Engels edition).

Then, in the fourth section, Marx sums up the how, with the apparent autonomy of interest vis-à-vis profit, the fetish character of capital is completed so that capital seems to be a mysterious entity capable of creating interest to augment itself. Even though interest is in fact one part of the total surplus-value created through the exploitation of labour, it seems instead that interest is the fruit of capital itself. These first four sections thus present the basic concept of interest-bearing capital in terms of its essence and what forms that essence must take.

Finally, Marx moves onto consider interest-bearing capital under the credit system in the fifth section. Ōtani further divides this section into three basic parts: (1) an outline of the credit system, (2) the proper analysis of interest-bearing capital under this system, and (3) inflow/outflow of bullion and the constraints of the monetary system on the credit system.

Marx needs to begin by clarifying the essence of the credit system because this is one of the premises (along with the concept of interest-bearing capital itself) for carrying out an analysis of the concrete form of “monied capital” under the credit system. This is a topic that Marx had not systematically dealt with up to this point in Capital. Along with clarifying the essential nature of the credit system, Marx also explains that interest-bearing capital (as well as money-dealing capital) appear in the concrete form of monied capital within the credit system.

Marx undertakes this analysis in the part of the fifth section that is labelled “The Role of Credit in Capitalist Production”.[21] He begins by discussing the two fundamental aspects of the credit or banking system. The first is upper layer of the system, which is the handling of various forms of credit based on commercial credit. The second is the management of interest-bearing capital. The latter function is precisely what transforms money-handlers into bankers. After having explained the essence of the credit system, Marx considers its role within capitalist production. This corresponds to Chapter 27 in the Engels edition. We learn how the system arose from various necessities of capitalist production, such as the need to minimise circulation time and costs and mediate competition between capitals. Marx also shows that once the system is established it promotes the further accumulation and concentration of capital.

Ōtani emphasises that this whole analysis of the credit system simply serves as preparation for the subsequent analysis of interest-bearing capital under it – rather than constituting an analysis of the credit system per se, as Marx does not enter into the details of this system. He is also careful to note that the credit system is shaped by the movement of capital (both productive and interest-bearing) rather than being an independent agent – a point that is obscured somewhat in the Engels edition.

Marx then analyses monied capital from the perspective of clarifying the concrete forms it assumes under the credit system and the relations and determinations underlying those forms, thereby clearing up the confusion that arises from ideas based on superficial appearances within the money market. This involves explaining how productive capital necessarily gives rise to monied capital. Even though monied capital becomes independent of the movement of industrial capital that produced it, so as to exert its own influence upon that movement. In the end, however, monied capital is determined and constrained by productive capital.

In his analysis of monied capital under the credit system, Marx looks at how monied capital takes the concrete form of banking capital, which operates in order to earn the interest that is the source of a bank’s profits. This analysis reveals that the forms assumed by banking capital, such as interest-bearing securities or a bank’s reserves, are essentially fictitious. Ōtani argues that although the fifth section of Chapter 5 is titled “Credit, Fictitious Capital”, Marx seems to be referring specifically to the fictitious character of banking capital.

As the final part of the analysis of monied capital within the credit system, Marx considers the relation of monied capital to “real capital”. According to Ōtani, this constitutes the core of the discussion of the fifth section. In particular, Marx considers two issues: (1) the relation between the accumulation (or shortage) of monied capital and the accumulation (or shortage) of real productive capital, and (2) the relation between the quantity of monied capital and the quantity of the means of circulation in a given country. Here, Marx clarifies how monied capital moves independently from real capital and reacts upon it, while, at the same time, being ultimately constrained and determined by real capital. In the course of this analysis, Marx thoroughly subjects the “confusion” that arises from the appearances of monied capital to critique.

Finally, as the third part of Section 5, Marx considers the inflows and outflows of bullion as the portion of monied capital that must form the reserve of the credit/banking system, thus constituting a constraint on the movement of monied capital. Ōtani observes that this final part concludes the consideration of monied capital in relation to real capital and brings the entire fifth section to a close.

After the elucidation of the theoretical development of interest-bearing capital, which demonstrates how interest-bearing capital is derived from industrial capital, Marx offers some historical considerations of interest-bearing capital in Section 6. This historical section is necessary to clarify the distinction between interest-bearing capital and usurer’s capital in precapitalist societies Marx shows how the emerging industrial capital assimilated the pre-existing forms of interest-bearing capital and subordinated them to its own functions.

Ōtani’s accomplishment and influence on Japanese Marxism

The above is only a thumbnail sketch of Ōtani’s research, based on his own account (Ōtani 1995), but it may at least point to the limitations that the Engels edition of Volume III imposed on a Marxist understanding of the capitalist financial system. Ōtani’s great accomplishment was to recognise that the main topic addressed by Marx in Chapter 5 of the manuscript for Book III was “monied capital” as the concrete form of “interest-bearing capital” under the credit (or banking) system, rather than an analysis of the credit system per se. Clarifying the concept of monied capital is essential for understanding not only the financial system as a whole but also the relationship between monied capital and real capital, which, in turn, is crucial to an understanding of the phenomenon of crisis.[22] Simply put, there is no way to come to grips with such phenomena as the “financialiaation” of the capitalist economy with understanding the essential concept of interest-bearing capital and monied capital as its phenomenal form. And this can only be accomplished fully on the basis of examining the original manuscript for Capital.

Even in Japan, Ōtani’s research on Marx’s manuscripts has yet to be fully assimilated, but a number of important works have appeared in recent years that have made it possible to understand Capital in the light of “new MEGA”. In 2023, a book by Korefumi Miyata appeared in which he examines the three books of Capital on the basis of the original manuscripts (Miyata 2023) and a year later Ryūji Sasaki published a detailed introduction to Book III that is also based on the new MEGA edition (Sasaki 2024), as the follow-up to his popular introduction to Book I (Sasaki 2018). A Japanese edition of Book III based closely on Marx’s original manuscripts is also under preparation now and will be published in the near future by Sakurai Shoten. Thanks to such resources, readers and scholars in Japan have had easier access to an “unfiltered” Marx. It is hoped that more and more Japanese research based on new MEGA will be made available in English in the years ahead.

References

Ehara, Kei 2018, “Teinosuke Otani: Marx’s Theory of Interest-bearing Capital”, in Marx-Engels Jahrbuch 2017/18, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, pp. 245–52).

Engels, Frederick 1995, Correspondence 1883–1886, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, Volume 47, New York: International Publishers.

Kuruma, Ken 2000, Kahei shinyo ron to gendai: Fukansei no riron (Money Credit in the Modern Era: The Theory of the System of Non-Convertibility), Tokyo: Ōtsuki Shoten.

Kuruma, Ken 2003, Shihonshugi wa sonzoku dekiru ka: Seichōshijō-shugi no hakai (Can Capitalism Survive: The Collapse of the Doctrine Prioritizing Growth), Tokyo: Ōtsuki Shoten.

Kuruma, Samezō 2024, In Pursuit of Marx’s Theory of Crisis, translated and edited by Michael Schauerte, Leiden: Brill.

Marx, Karl 1981a [written 1864–65], Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume 3, translated by David Fernbach, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

Marx, Karl 1992, Ökonomische Manuskripte 1863–67, in Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe Abteilung 2, Band 4.2, Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

Marx, Karl 1994, Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, Dritter Band, in Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe Abteilung 2, Band 15, Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

Miyata, Korefumi 2016, “Karl Marx’s Credit Theory. The Relation between the Accumulation of Monied Capital and the Accumulation of Real Capital”, in Marx-Engels Jahrbuch 2017/18, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, pp. 10–27).

Miyata, Korefumi 2023, Marukusu no keizai riron: MEGA-ban “Shihon-ron” no kanōsei: Marx’s Political Economy: The Potential of the MEGA-edition of Capital, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Ōtani, Teinosuke 1995, “Marukusu no rishiumi shihon ron” (Theory of Marx’s Interest-bearing Capital), in Marukusu no rishiumi shihon ron: 1 kan (Theory of Marx’s Interest-bearing Capital: Volume 1), Tokyo: Sakurai Shoten, pp. 41–71.

Ōtani, Teinosuke 2003 Marukusu ni yotte, Marukusu o amu (Weaving Marx through Marx), Tokyo: Ōtsuki Shoten.

Ōtani, Teinosuke 2011, Marukusu no asoshieshon ron: Mirai shakai wa shihonshugi no naka ni mieteiru (Marx’s Theory of Association: Getting a Glimpse of a Future Society within Capitalism), Tokyo: Sakurai Shoten.

Ōtani, Teinosuke 2016, Marukusu no rishiumi shihon ron (Theory of Marx’s Interest-bearing Capital; 4 vols.), Tokyo: Sakurai Shoten.

Ōtani, Teinosuke 2018, Shihonron sōkō ni Marukusu no kutō o yomu: “Shihonron” dai ni bu dai hachi kō zenbun to sono kanren shiryō o shūroku (Reading Marx’s Struggles in the Manuscripts of Capital: Complete Text of Eighth Manuscript for Book II of Capital and Related Materials).

Ōtani, Teinosuke 2018, A Guide to Marxian Political Economy: What Kind of a Social System Is Capitalism?, Cham: Springer.

Sasaki, Ryūji 2018, Marukusu shihon-ron (Marx’s Capital), Tokyo: Kadokawa.

Sasaki, Ryūji 2024, Marukusu shihon-ron dai sank kan (Marx’s Capital Vol. 1), Tokyo: Kadokawa.

[1] Japanese names in this article are listed in the “Western” order, with the surname last, in part because Ōtani himself listed his own name in this order for his English- and German-language papers.

[2] A separate editing team was established in Sendai that was headed by Izumi Ōmura, who was also a member of the IMES editorial board.

[3] Kei Ehara has reviewed the four volumes of Marx’s Theory Interest-Bearing Capital in English, situating Ōtani’s work within the context of the debate between Kōzō Uno and Yoshio Miyake over Part 3 of Volume III of Capital (Ehara 2018). Korefumi Miyata also touches on some aspects of Teinosuke Ōtani’s research on interest-bearing capital in his paper “Karl Marx’s Credit Theory. The Relation between the Accumulation of Monied Capital and the Accumulation of Real Capital” (Miyata 2016).

[4] One of the weaknesses of Japanese Marxism up to that point was the lack of debate over the meaning of socialism. Left-Communist and Trotskyist tendencies were absent in Japan in the 1920s and 1930s. In the 1950s, Tadayuki Tsushima presented a theory of state capitalism in his book Kuremurin no shinwa (Myths of the Kremlin), but it was primarily based on the writings of Raya Dunayevska, Tony Cliff, and others. In the 1970s, Hiroyoshi Hayashi developed a more coherent and original theory of state capitalism, and Tsuyoshi Nakamura and others presented the concept of council communism, but none of these theories exerted much influence outside of their own organisational circles.

[5] Ōtani’s ideas on the dimensions of a post-capitalist society are presented in his book Marx’s Theory of Association: Getting a Glimpse of a Future Society within Capitalism (Ōtani 2011).

[6] Ken Kuruma’s writings on money and the modern financial system are gathered in his book Money Credit in the Modern Era: The Theory of the System of Non-Convertibility (Ōtsuki Shoten 2000).

[7] Ōtani 2003, p. 35.

[8] Ōtani 2003, p. 37.

[9] English translations of the editorial conversations for the four Marx-Lexikon volumes on crisis can be found in In Pursuit of Marx’s Theory of Crisis (Kuruma 2024).

[10] Satō’s paper built on the prewar work of Samezō Kuruma. At the same time, he criticises the limitations in Kuruma’s understanding of “capital in general” that arose from his unfamiliarity with the Grundrisse, which was unknown to Marxists in Japan until the publication of the second German edition in 1953.

[11] No claim to originality can be made for my summary of the research that follows, as it is mainly a synopsis of Ōtani’s own introduction to his research on interest-bearing capital (Ōtani 1995).

[12] Ōtani 1995, p. 246.

[13] Marx 1981, p. 93.

[14] Ōtani 1995, p. 253.

[15] Marx 1981, pp. 94–5.

[16] 13 November 1885 letter to Nikolai Danielson; Engels 1995, p. 348.

[17] This is modelled after the table that appears in “Miyata 2016” (p. 13).

[18] Marx 1992, p. 469.

[19] Marx 2004, p. 432.

[20] Marx 1992, pp. 504–5.

[21] Marx 1992, p. 501.

[22] See Miyata 2016 for more on the “plethora of monied capital” and its relation to crisis and the accumulation of real capital.