In October 1994, I opened one of those light blue Royal Mail International Aerogrammes that periodically crossed my desk in times past from friends in the United Kingdom. This one was from John Saville, of whose support and generosity I had been the beneficiary since our first meeting at a gathering of “Commonwealth Labour Historians” in 1981.

John wrote about a number of things, but his letter was most concerned with a recent Times Higher Education Supplement that carried a review by his old friend and comrade, Christopher Hill. A revered Marxist authority on 17th century England, Hill reviewed my homage to E.P. (Edward) Thompson. The book in question was originally a long, two-part essay written for the Canadian journal Labour/Le Travail. Produced in haste and out of sadness at the death of arguably the most significant working-class historian of the twentieth century and an indefatigable campaigner for just causes, this obituary-like reflection attracted the attention of Michael Sprinker, an editor at Verso. The New Left publisher put out E.P. Thompson: Objections and Oppositions a year later. John took exception to Christopher’s use of the THES review to characterise what might have been had Edward not taken his leave from the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) with Saville and countless others in 1956, and closed with the conviction, “No doubt we shall discuss …”.[1]

Having not seen the THES review, I made my way to the library to have a look. Hill’s review was both personally wounding and intellectually and politically troubling. One part of this was the high regard in which I held Hill. To be criticised by Christopher – whom I had met, once and briefly, at a November 1980 New York conference where he delivered a talk on “Radical Pirates” – was certainly disconcerting, although his review did open with the acknowledgement that, “This is a timely and useful book”. That said, from there it was largely downhill.

I thought Christopher inexplicably mistook what the book was. I made clear on the first page of a preface what the reader would not be getting: my book was not the full biography Thompson deserved. Such a study was impossible so close to Thompson’s death, and would necessarily be based on deep, and wide-ranging, archival research. Rather, my short book was a suggestive contemplation, memoir, and appreciation. Other reviewers understood the limitations of a publication completed so quickly after Edward’s death, situating its contribution within a particular historical context. Hill clearly expected more. Surprisingly, given Thompson’s significance we still lack, more than three decades later, a full and satisfactory biographical treatment of this major figure.[2]

Hill’s decision to use the limited space of a review of E.P. Thompson: Objections & Oppositions to settle accounts with Edward over the Communist Party and the events of 1956-57 was what was most disappointing. According to Hill, the exodus of some 7,000 members from the CPGB had been “fired by Thompson’s protest, resignation and propaganda”. He further suggested that if “they had remained in the party to fight for democracy the outcome might have been different”. Many who resigned, such as himself, Hill now claimed, “felt that Thompson’s precipitate actions had made defeat a certainty. We held that he should have stayed to fight within the party instead of ensuring its decline into insignificance”. Who those others were, and why they had not voiced their grievances, were questions that Hill did not answer. Christopher’s conclusion, arrived at under the THES title, “The Shock Tactician”, was somewhat barbed, given that he and Thompson had been on good terms for decades. “The walls of Jericho did not fall at the blast of Thompson’s trumpet”. Destroying the Communist Party that had a “distinguished agitational history … was not a victory for any cause that Thompson claimed to believe in”.[3]

Hill closed his review with acknowledgement of Thompson’s justifiably lauded historical writing, for which he professed admiration “second to none”. Yet there was no mistaking his view that Edward’s “righteous wrath” was unduly counter-productive. There was a personal dimension to all of this. Tariq Ali recently recounts that, decades after the events of 1956-57, Hill told him that the “rudest and most obnoxious letter I have ever received in my life was from Edward”, who railed against Christopher for “taking too long to leave the CPGB”. The man E.P. Thompson dedicated Whigs and Hunters: The Origin of the Black Act (1975) to as “Master of more than an old Oxford College” clearly did not take kindly to “rude” chastisement. Hill might concede Thompson’s insistence that expressions of anger, indignation or even malice could be genuine. But there were, in Christopher’s view, limits; he did not appreciate Thompson’s implied criticism that such controls likely revealed “a concealed preference … for the language of the academy”. This was a stand Edward had taken in an early New Left Review critique of Raymond Williams, an essay that Williams subsequently recalled caused him considerable pain.[4]

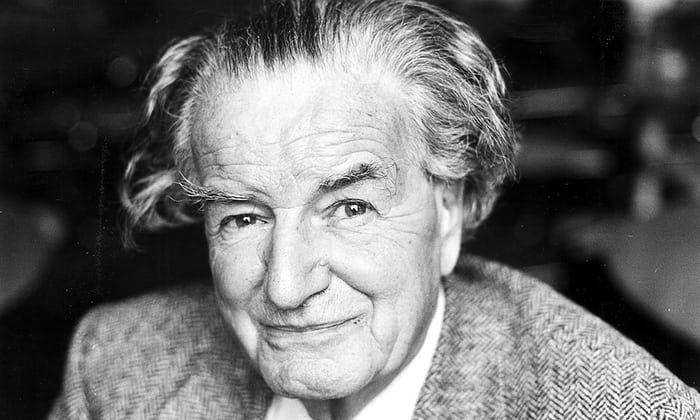

All of this came back to me as I read Michael Braddick’s recent Verso-published Christopher Hill: The Life of a Radical Historian (2025). Braddick’s book, a long overdue biographical study of Hill, has much to recommend it. The book conveys reasonably well Hill’s contributions to the history of seventeenth-century England. This is no mean feat, given that Hill’s command of the period’s events and printed sources was so monumental as to make a thorough and imaginative tour through his oeuvre an undeniably daunting task.

What was perhaps most distinctive and, to many of us associated with the ethos of the 1960s, most endearing about Hill was his defiant and unrepentant stand against complacent autocracy. The American Marxist historian closest to Christopher in terms of subject area and interpretive approach, C.H. George, once told me over a drink what he thought made Hill tick. George regarded Hill as that rare historian who actually delighted in the beheading of a King, Charles I. This, George insisted, enlivened Christopher’s immense scholarly production. Hill revelled in the radical antinomianism of the seventeenth century, with its republican regicide as the political rejoinder to the divine right of kings:

Monsters which knaves ‘sacred’ proclaim,

And then like slaves fall down before ‘em.

What can there be in kings divine?

The most are wolves, goats, sheep or swine.

Then farewell sacred majesty,

Let’s put all brutish tyrants down;

When men are born and still live free,

Here every head doth wear a crown.[5]

This was heady stuff in the 1960s and early 1970s, when there was an appetite among young radicals for the root-and-branch revolutionary transformation of society and a hard-edged refusal to bow to heredity authority.

The current conventional wisdom is that Hill’s view of the seventeenth-century is outdated, displaced by superior, sophisticated studies. Braddick too easily echoes this view. I am no specialist in the field, but I do know that historiographic fashion is quite fickle and moves with the political times. Hill’s reception has, no doubt, suffered of late, but it could well revive when the terms of trade in the political culture shift from right to left. I, for one, am forever thankful to have the library shelf of Hill’s titles.

Braddick also highlights the progressive role Hill played at the influential Oxford College, Balliol, where he was master, jokingly referred to by his friend, Richard Cobb, as “SuperGod”. Hill rightly comes across as an unassuming, quiet and reflective leader, respectful of tradition but never standing on expectations of ceremonial obeisance. Politically, Braddick, who has genuine interpretive differences with Hill, quietly dispenses with a good deal of the ideological nonsense that circulated about the former Communist Party member, accused of being a spy for the Soviet Union. This was nothing more than post-Cold War red baiting and cheap conviction by innuendo. That a residue of this ugliness continues is evident in the cute but offensive title of the Times Literary Supplement review of Braddick’s biography: “A Stalinist Chump at Oxford”.[6]

When John Saville wrote to me in 1994 about Christopher’s review, he reflected on Christopher’s delay in leaving the Communist Party in 1956-57. “Edward and I knew he wasn’t with us during the summer of the Reasoner [ed., 1956]”, Saville noted, adding that the two dissident communists assumed that Hill’s “experience on the internal commission on party democracy … made him realise the old guard would never change and just as important that at the conference of spring 1957 the mass of delegates were against him, and us”. Saville insisted it was not Edward who alienated the many trade unionists who exited the CPGB: they “were not readers of the Reasoner”.

Lawrence Daly, a coal-miner militant born into a Communist family, and the future founder of the Fife Socialist League, left the Party in August 1956, before establishing contact with the Reasoner. Similarly, the Fire Brigades Union leadership left the CPGB en masse without any influence from Thompson, Saville, and others. Labour movement figures departed the Party, Saville claimed, because after Khruschev’s 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union speech of 1956, and the repressive Hungarian events later that year, disillusionment set in.

Christopher’s memory, according to Saville, was taking a distorting “interesting twist”. The commission on inner-party democracy that Hill participated in before resigning led to Christopher signing off on a minority report that he stated publicly he did not agree with entirely. Co-signators were Peter Cadogan and Malcolm MacEwan. Saville was adamant that Hill “quite misjudges or forgets what happened”, and the minority report could never have won over the majority of CPGB delegates. Claims that Thompson destroyed the CPGB, when other Moscow-affiliated parties around the world went into the same kind of post-1956 tailspins as their British counterpart, or that the Party Hill so desired to change was realistically able to be reformed were not sustained by evidence. The argument was “nonsense” Saville concluded.[7]

Like John Saville, Dorothy Thompson took issue with Christopher Hill. She wrote to Hill to express disagreement with “some aspects of your account of the ’56 events”. Dorothy challenged Christopher’s focus on Edward as the animating force behind both the Reasoner group and the approach it took in responding to the CPGB crisis. Dottie recalled that she dissuaded Edward and John Saville from resigning “quietly … persuading them that they should stay in until they were expelled in order to make the arguments convincing”. Dorothy also offered an insightful comment: there may well have been a generational difference separating out the response of the Reasoners and an older cohort of Communists such as Hill. “We had after all, been 15 when the war broke out”, Dorothy noted; “had none of us been to the SU or had much to do with the CP in the ‘thirties”. She was flummoxed by James Klugmann’s perplexed response at the reaction to 1956’s revelations. Dorothy and Klugmann always got along well, and, as they talked, he confided that “he couldn’t understand why ‘this Joe business’ upset” Dottie so much. The Dorothy Thompson-Hill correspondence, while critical, was warm and congenial. Dorothy Thompson closed with “much love” to Christopher and his wife Bridget.[8]

Christopher replied to Dorothy in kind, John Saville rightly characterising Hill’s response as “friendly and civilized”. Hill conceded that the generational aspect of who left the Party and who stayed in and desired reform was something worth considering and that he “hadn’t thought of that before”. Edward, Hill agreed, was certainly not the “sole instigator of the Reasoner group”, but he focused on him nonetheless because he was “its most articulate and effective spokesman”. Beyond this, Christopher was unrepentant: “we can only agree to differ about the far-away events of 1956-7”. He noted the many “weary months of hard labour” that went into the writing of the minority report, a document which made “the right sort of suggestions”. Christopher proudly reported to Dorothy the Vice-Chancellor of Glasgow University describing the document as “impeccably liberal” at the same time as he refused Hill “a job because of my political opinions”. Most tellingly, Hill recalled that the minority report “just failed to become the committee’s majority report because at the last minute King St. [ed., CPGB leadership] put some sort of pressure on a very good working-class comrade who had been with us all the way up to then”.[9]

This was precisely the kind of evaluation John Saville, whom Dorothy shared Hill’s letter with (as she may have with Martin Eve who, like Christopher, stayed in the Party until 1957, but who sided with Dottie on his understanding of what had happened), dissented from. John insisted that there were “only two working class members who had great sympathy with the minority report”, and that “the solid bloc of party functionaries would never have shifted”. Saville thought, “It really is very unhistorical for Christopher to write in these terms”.[10]

None of the correspondents I am quoting wanted to get into a public debate in 1994. So why does this matter? To many, it will not. My sense is that the significance of these letters is twofold. They detail why Christopher Hill, in 1994, felt compelled to raise the interpretation he did of 1956-57 when he had not done so publicly before this. And they shed light on how this is presented in Braddick’s study of Hill. Braddick had access to at least some of the correspondence in my possession. He alludes to it, but in ways that prompt reconsideration. The letters therefore illuminate analytical issues central to the history of the revolutionary left in the twentieth century as well as prompting thought about historical method.

On the why of Hill’s 1994 reconstruction of the 1956-57 CPGB crisis, and what I take to be a naïve assumption that it would have been possible to reform the Communist Party, Christopher explained to Dorothy Thompson that, by the time the minority report of the commission on inner-party democracy was eventually available:

King St.’s tactic of playing for time had paid off. Too many people had left the party in disgust without staying in to fight the forlorn hope battle for reforming or changing the leadership. The result was to destroy the party as a viable reforming organization of the left, and nothing has replaced it. I cannot think this was a desirable outcome. … What I most bitterly regret about the events of 1956-7 is that we now have no such organization. The ‘New Left’ contained many powerful personalities but never amounted to a coherent party which could attract a mass backing to do the sort of job which the CP did in the 30s and 40s and which still desperately needs doing.

John Saville, adamant that Hill was wrong on much, nevertheless thought Hill’s explanation of why he was taking the stand he did in 1994 “very much to his political credit”. Most of Christopher’s generation, Saville told me sadly, “have in fact given up”. In the climate of the 1990s, with the Labour Party under Tony Blair embracing neoliberalism and the “Third Way”, the far Left in the throes of disintegration, and the CPGB an antiquated irrelevance, Saville wrote to me that “we are desperately in need of a much stronger Left political current; and that cannot come about without a political organization. But you know the problem”.[11]

There is, nonetheless, a problem with how this appears in Braddick’s book. Hence this note, something of a footnote to what Saville considered Hill’s 1994 interpretive folly, “what can only be described as … fantasies of what might have happened”.[12]

Saville was unwavering in his view that Christopher’s position around 1956-57 in his THES review of my book was an about-face. “I’ve known C. since 1939 and he has never indicated anything like this before”. At the CPGB Congress in April 1957, those like Hill who advocated reform were subjected to a Stalinist fusillade. Denounced as lacking political backbone, Hill and others were assailed as “spineless intellectuals”, told to “take their medicine”. Christopher responded. His tone, as it so often was, conveyed admirable restraint and conciliation, acknowledging that the “world of illusions, … a smug, cosy little world”, was one that all Communists had a hand in creating: “We are all responsible for the bad state the Party has got into, for taking lines from the top”. The minority report Hill endorsed was resoundingly defeated, 423 to 23 with 15 abstentions. That decisive count alone lends credence to Saville’s jaundiced judgement about the possibilities of reforming the Party, and casts considerable doubt on Hill’s more guardedly optimistic assessment almost three decades later.

On May Day 1957, Hill offered his resignation from the CPGB. He largely conceded that Thompson and Saville had been correct in their assessment of the situation, confirming Saville’s view that Hill’s 1994 comments represented a departure from his past positions. Sometime in 1957, Margot Heinemann sent a letter to John, reporting that she had conversed with Christopher, whom she quoted as saying, “I am only ashamed I didn’t move as fast and see as clearly as John and Edward”. Into the 1980s, Hill would confess, “I was a sucker for Stalinism until I found out a lot more about it. I thought the Communist Party held out an alternative. I was wrong”.[13]

This is all a little muddled in Braddick’s telling because he elides the historical context of 1956-57 and a much later, and backdated, reconsideration. In 1956, Hill undoubtedly harboured illusions in the possibility of Party reform, at least for a time. But the hopeful mirage quickly faded, and Hill acknowledged this. Braddick offers up the October 1994 correspondence between Dorothy Thompson and Christopher Hill as evidence of Hill’s 1956-57 commitment to reform the Party and his foresight that the New Left, fractured and incapable of sustaining a mass base, would inevitably fail. This puts the cart of afterthought before the evidence of historical situation and how it was perceived at the time.

What is therefore understated is the extent to which Hill, in the aftermath of his drubbing at the 1957 spring conference and his resignation from the CPGB, recognised that the Party was not open to reform, which was the undeniable reality of the period. Moreover, while Hill was right in his 1994 assessment that the New Left proved incapable of building an alternative to a disciplined communist party, there is scant evidence that, in 1957, he had, as Braddick implies, grasped the inevitability of this failure.

There is no indication in Braddick’s account that Hill’s 1994 views could have constituted a retrospective realignment. Positions that evolved and grew out of disappointment and desperation associated with decades of political developments and that crystallised in the 1990s are thus parachuted back into the crisis of 1956-57, the suggestion being that they were rooted in this earlier period and exhibited an unproblematic continuity carrying forward for decades. Hill’s claims about 1956-57, and his justification of them in correspondence with Dorothy Thompson are in my view better placed in Braddick’s penultimate chapter, “Retirement, Revisionism, and the Experience of Defeat: 1978-2003”.

There is no doubt that Hill remembered and resented Thompson’s rudeness in challenging him in 1956, but there is also little to suggest that, for the decades spanning the late 1950s into the early 1990s, Hill ever repudiated the Reasoners or suggested the inevitability of New Left failures. It is of course possible that Hill was always sceptical of the New Left’s potential, but the critique that he would adopt in 1994 was premised on the need to retain something of what the Communist Party was in 1956-57, while rejecting other aspects of the organisation.

History would reveal that the promise of the New Left was to be unrealised. Did Hill really anticipate this in 1956-57? If so, there is little indication, in the late 1950s and 1960s, that Hill voiced much in the way of criticism of the nascent New Left. There is even some suggestion that Hill thought a new political orientation might lead to something positive: less than a month after Hill’s exit from the CPGB, he was writing to Saville urging co-ordination of the New Reasoner and the Oxford-based Universities and Left Review. The merger of these projects would eventually lead to the establishment of the New Left Review. But the kinds of political disillusionment that the late twentieth century unleashed for the left, combined with how Thompson’s calling Hill to account in 1956 still rankled after decades of close Thompson-Hill friendship and compatibility, could culminate in a skewed, decontextualised, and personalised reconstruction of the past.[14]

Christopher Hill was by no means hostile to the countercultural, bohemian sensibilities of much of the 1960s New Left. Braddick demonstrates this, and a reading of the wonderfully evocative and quintessentially Hill study, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (1972), confirms the point. As Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker show in a review of Braddick in The Nation, Hill was, in some ways (including his distance from the kinds of organisational initiatives that Thompson struggled to keep alive, such as the May Day Manifesto initiatives of 1967-68), the most New Left of all the distinguished historians to pass through the Communist Party Historians Group. There is no denying, however, that he was also, in the 1940s and 1950s, perhaps the most deferential to Stalin. All of the Communist historians I have been discussing were, during much of their time in the CPGB, on the same page with respect to this kind of adoration, even Thompson. This was, by the 1990s, Hill’s cross to bear. The burden of it all was clearly onerous.[15]

Through time — struggles, victories, and perhaps most decisive for recent generations, the experience of defeat — change happens. It is not always for the better, and judgements can err on the side of wishful thinking as often as they are able to provide much needed insight. In a 1984 book, The Experience of Defeat: Milton and Some Contemporaries, Christopher Hill wrote that, “The experience of defeat meant recognizing the collapse of the system of ideas which had previously sustained action, and attempting to discover new explanations, new perspectives”. Milton, Hill insisted, was that rare seventeenth-century radical whose “experience of defeat led him to take his” role as a poet and prophet “not less but more thoroughly”.[16] Braddick’s representation of Hill’s place in the events of 1956-57, his experience of defeat gathering momentum over the 1980s and into the 1990s, and his 1994 reassessment of what might have been, filtered through decades of left-wing fragmentation and resignation – all of this poses questions.

Historical contexts matter, and memory, always fallible, can often conveniently skirt them. If this footnote to a folly has meaning, it suggests that congealing historical occurrences together, presuming prior actions to have been guided by later conclusions, is a perilous way of understanding the past. Braddick’s book, illuminating in so many ways, offers us a view of 1956-57, and Hill’s negotiation of that crisis in the Communist Party, that cries out for interrogation. The biographer of the historian chastised for his lumping historically situated ideas indiscriminatingly together rather than splitting them into more refined differentiations has ironically, in one small instance at least, fallen prey to the criticism directed at his subject.[17]

[1] Saville to Palmer, 12 October 1994. All private communications cited are in possession of the author.

[2] See, for instance, Frank McLynn, “To Build Jerusalem”, New Statesman & Society, 11 November 1994: “The time has not yet come for a full biography of E.P. Thompson, who died last year, but, until it does, Bryan Palmer’s useful volume provides the bare bones of a career. … Meanwhile, this interim report is very welcome as it reminds us how much the British left owes to this great radical dissenter”.

[3] Christopher Hill, “The Shock Tactician”, Times Higher Education Supplement, 7 October 1994.

[4] Tariq Ali, You Can’t Please All: Memoirs, 1980-2024 (London: Verso, 2024), 73; E.P. Thompson, “The Long Revolution, 1”, New Left Review, 9 (May-June 1961), p. 25. The letter Ali recounts Hill mentioning is undoubtedly that referenced in Michael Braddick, Christopher Hill: The Life of a Radical Historian (London: Verso, 2025), p. 124. Braddick does not cite an actual copy of the communication, but an allusion to it in Penelope J. Corfield’s recollection of Hill, her uncle. Since Braddick has conducted a thorough search of Hill’s Papers, it is possible that Thompson’s letter to Hill is not located there. It might well have been misplaced, even destroyed, or, more likely, Hill sent it to Dorothy Thompson to deposit in E. P. Thompson’s Papers after Edward’s death. Dottie asked all of Edward’s correspondents to forward letters to her so that they could be placed in her husband’s papers. Those papers are not yet accessible.

[5] Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (New York: Viking, 1972), p. 335.

[6] Richard Davenport-Hines, “A Stalinist Chump at Oxford: The Civil War historian who misjudged his times”, Times Literary Supplement, 21 March 2025, https://www.the-tls.co.uk, accessed 20 May 2025. I say cute only because the title obviously echoes the 1940-released Laurel and Hardy film, A Chump at Oxford, itself a parody of a 1938 film, A Yank at Oxford.

[7] Saville to Palmer, 12 October 94; Saville to Palmer, 17 November 1994.

[8] Dorothy Thompson to Hill, 21 October 1994, sent to B.P. in confidence. I have kept Dottie’s request for confidentiality around this letter and Christopher Hill’s response, quoted below, for more than 30 years. But with all parties involved in the communications long dead, and with these same documents available in the accessible archival papers of Christopher Hill and John Saville, and some cited by Braddick, it now seems beside the point to keep them private.

[9] Hill to Dorothy Thompson, 30 October 1994.

[10] Saville to Palmer, 12 October 1994; 17 November 1994.

[11] Hill to Dorothy Thompson, 30 October 1994; Saville to Palmer, 17 November 1994.

[12] Saville to Palmer, 17 November 1994.

[13] Saville to Palmer, 12 October 1994; Braddick, Christopher Hill, esp. pp. 128-39, 241.

[14] The only indication of Hill’s views of 1956-57 that I have come across suggesting any affinity with what he wrote in his 1994 review of my book is a memoir posted online by his niece, Penelope J. Corfield, “Christopher Hill: The Marxist Historian as I Knew Him”, 4-5, https://www.penelopejcorfield.com, accessed 20 May 2025. Corfield’s relevant recollection of her conversations with Christopher appeared long after 1994. This essay conveys Hill’s sadness that the dissident Communist reformers did not prevail, but does not reiterate his negative assessment of Thompson’s role in destroying the CPGB, let alone suggest that Christopher was convinced in the late 1950s that a New Left would inevitably fail. For Hill’s suggestion to Saville concerning the two New Left publications, see Braddick, Christopher Hill, p. 127.

[15] Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, “The World Turned Upside Down: Christopher Hill’s History from Below”, The Nation, 13 May 2025, https://www.thenation.com, accessed 20 May 2025. Other recent reviews of Braddick are congruent with this understanding of Hill as well. See Raphael Magarik, “Christopher Hill: Pioneer of History from Below”, Jacobin, 5 May 2025, https://www.jacobin.com, accessed 20 May 2025; Stefan Collini, “Agent of Injustice”, London Review of Books, 47, 22 May 2025. On Hill and Stalin see Paul Flewers and John McIlroy, ed., 1956: John Saville, E.P. Thompson & The Reasoner (London, Merlin, 2016), esp. p. 356; Christopher Hill, “Stalin and the Science of History”, Modern Quarterly, 8 (Autumn 1953), pp. 198-212. E. P. Thompson’s William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1955), contained a number of “casuistries explaining away what one should have repudiated in the character of Stalinism”, among them: “Were William Morris alive to-day, he would not look far to find the party of his choice” (p. 795); and praise for “Stalin’s blue-print of the advance to Communism” (p. 760).

[16] Christopher Hill, The Experience of Defeat: Milton and Some Contemporaries (London: Faber & Faber, 1984), pp. 17, 328.

[17]For the critique of Hill and splitting and lumping, at times quite rancorous, see J.H. Hexter, “The Burden of Proof”, Times Literary Supplement, 24 October 1975. Hexter’s critique was no doubt animated by animosity to Hill’s attraction to radicalism, and Braddick provides useful background suggesting its lack of originality. He also notes that although Hexter’s attack upset Hill as unduly personalised, Christopher later mended fences with Hexter, who was entertained in the Hill household. Bridget Hill declared, with respect to Hexter: “It was difficult to hate him”. See Braddick, Christopher Hill, pp. 162-64, 200.