With its provocative title, Andreas Malm’s 2021 How to Blow Up a Pipeline broke out of the left ghetto and gained mainstream attention for the argument that the climate change crisis is so severe that direct action is justified. Certainly, we need more mass protest and campaigns to push for change. But Malm wants to go further, lauding disruptive direct-action tactics and suggesting that Extinction Rebellion is too tame.

As far as I know, neither Malm, nor anyone who has read the book, has yet actually blown up a pipeline to protest against climate change. But the vicarious idea of direct action by the few in the name of the many remains popular. Malm sees to want to contribute to this, while also saying he really prefers mass protest. Unfortunately, his analysis of what distinguishes mass action from the action of the few is fuzzy, as is his discussion of what separates ‘direct action as prank’ from direct action as major sabotage.

His analysis of why this should happen is also weak. Like many on the Left, he seems to think it sufficient to attack the private jets, yachts, and SUVs, as if the problem is the super-rich alone. But he must know that, if they were all banned tomorrow (as they should be), the bigger part of the climate change would still exist.

Similarly, by evoking a motley collection of examples of direct action from the past, he seems to hope that no one will notice the problems in his discussion. One of the most important, which he is not alone in using, is that of those Suffragettes who used direct action in the UK before 1914 in the fight for votes for women.

But what of this discussion? Well – let us be frank – it is so awful that it needs to be blown up as a warning lesson for how bad history and bad politics meld together.

Suffragettes – the fantasy versus the reality

Before 1918, all women in Britain were denied the right to vote in general elections. A broad women’s movement fought to change this. But there is no evidence that the mainstream Suffragette movement supported direct action beyond that they thought necessary for gaining the vote. Innocent readers would have no idea that the Suffragette leaders were supporters of parliamentary change. Their problem was that not having the vote, women could not directly access this.

But the problems go deeper. The name Suffragette is particularly associated with the women only Women’s Social and Political Union dominated by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. Other women wanting the vote tended to call themselves suffragists. The WSPU was never the biggest organisation either. That was the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. Nor did the WSPU have the most democratic demands. It was prepared to compromise on a limited property-based suffrage for men and women.

After 1906, the women’s movement as a whole became more militant. This militancy took the form of mass protests with huge demonstrations. Other organisations too, alongside the WSPU, supported ‘deeds not words’. What they did not support was the later direct action of the Suffragettes.

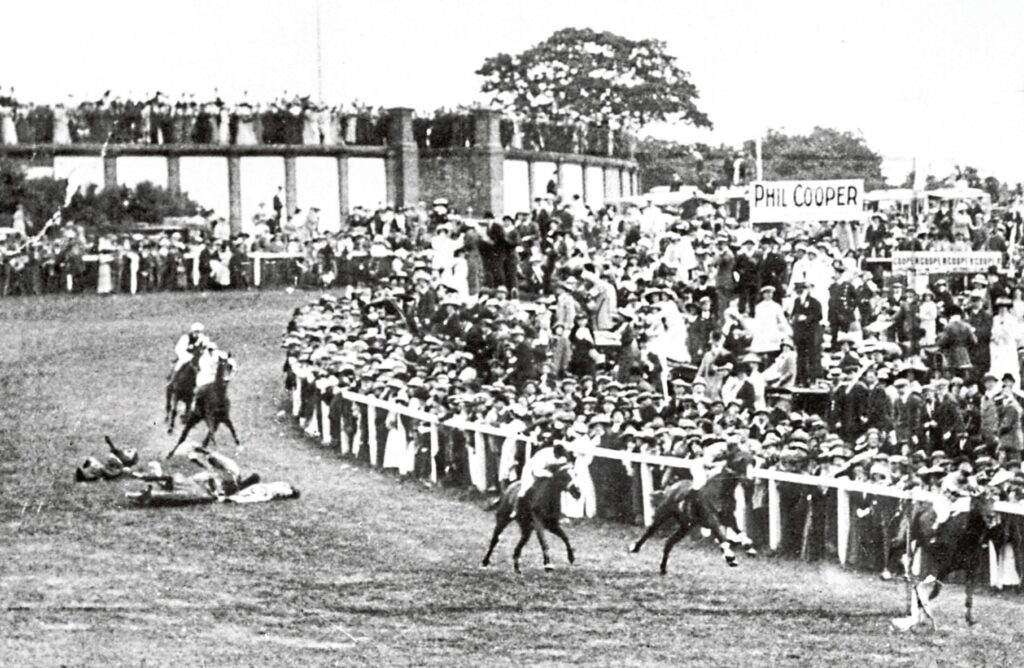

After the Liberal government of the day side-lined voting change, the leaders of the WSPU decided on more violent direct action in the years 1912-1914. The result was more civil disobedience and a rash of attacks on property ranging from breaking windows, destroying the post in post boxes, attacking works of art, arson, bombs and attacks on individual politicians.[1]

It is indisputable that, in doing this, the WSPU Suffragettes broke with the conventional idea of how women should act. It is indisputable also that they showed enormous courage – some dying for the cause, others being imprisoned, treated brutally, and going on hunger strikes. But the key issue is what impact did their actions have?

You would not know it from Malm’s account, but many historians, including feminist ones, think that the Suffragettes’ direct action actually derailed the movement for the vote. You can best access the debate by looking at a discussion in the Women’s History Review.[2]

What is the case against the Suffragettes?

It starts with the fact that the WPSU, with Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst at the top, was a completely undemocratic organisation. Emmeline was, said one of those who lost her favour, ‘a dictator without mercy’.[3] The WPSU was – to use a modern term – sectarian. There were splits with other organisations and splits internally as those who opposed the Pankhursts were driven out – including Emmeline’s famous left wing daughter Sylvia who Malm omits to mention. Yet it was Sylvia who was the bravest of the family and punished perhaps all the more by the state because she wanted to build a mass democratic movement.[4]

The focus on individual or small group actions in the WPSU intensified its political traits. How much of the direct action followed instructions from Emmeline and Christabel is disputed. But it is difficult to deny that the measures had to be carried semi-secretly. The people undertaking a lot of the actions were few in number and a significant number were actually employees of the WPSU. Emmeline, on the other hand, disappeared to the USA for a period and Christabel lived, as Barbara Winslow put it, ‘in comfortable, self-imposed exile in Princess Polignac’s palace in Paris’.[5]

The economic effect of the direct actions was quite modest. They did not encourage mass political support for the vote for women. To the contrary, anti-suffrage campaigners were emboldened. The Government saw the suffragette actions as an excuse to do nothing and the other suffrage campaigners were furious. Nor did the WPSU gain internally. It had rich backers and extraordinary finances but, in other respects, most historians consider it to have been in deep difficulties in 1914 with its modest membership falling.[6]

Sex and War – the Suffragettes and Gandhi hand in hand?

Malm ridicules those who invoke a supporter of non-violence like Gandhi against the direct action of the Suffragettes. Malm says that Gandhi’s position was compromised by his weird ideas about sex and support for British imperialism and World War 1.

The issue here is not Gandhi. But how on earth is it possible to read anything about the Suffragettes without understanding that they did exactly the same? They were obsessed with sex, venereal disease, and white slavery. For Christabel Pankhurst, it was ‘votes for women and chastity for men’. And as for the war? Are you kidding me?

The Suffragettes suspended open campaigning for the vote in order to support the war effort. Emmeline Pankhurst worked with the government for the mobilisation of women – including having secret meetings with Lloyd George. With her close supporters, she organised state subsidised demonstrations for the war and war work. She supported the internment of aliens; she wanted civil servants with German blood dismissed. Should I go on?

The magazine The Suffragette was renamed Britannia in October 1915. Men were urged to do the men’s work of fighting and dying for their country. She opposed strikes, supporting women in strike breaking. She was ‘an out an out imperialist’[7] who went twice to North America to encourage support for the war and spent several months in Russia in 1917 to help try to keep the Provisional Government in power.

It was Emmeline and Christabel’s Pankhursts’ support for the war effort that made them popular. (Emmeline repudiated the anti-war stance of her two other daughters Sylvia and Adela.) Lloyd George later wrote to Bonar Law that Emmeline Pankhurst and her supporters had ‘been extraordinarily useful, as you know to the Government – especially in the industrial districts where there has been trouble during the last two very trying years. They have fought the Bolshevist and Pacifist enemy with great skill, tenacity, and courage’.[8]

But, if the pre-war militancy was not the factor gaining women the vote, neither was the wartime patriotism of the Suffragettes. Annie Kenney, perhaps the leading member of the WSPU with a working-class background, said ‘we gained nothing by our patriotism. No money, no lasting position. By Armistice we were tired out, no homes, no job, no money, no cause. Forgotten’.[9]

Celebrating a wrong model

So, Malm’s naïve history leads him to laud the direct action of an organisation that was effectively run as a dictatorship with a paramilitary character; that drove out dissidents; an organisation that depended disproportionately on the financial support of the rich; that set itself against the labour movement; that alienated masses of people; that undercut bigger and more powerful campaigns; and that ended up supporting mass bloodshed.

And what happened next? Emmeline died a Tory party candidate and although some of her friends turned left others went on to support the Black Shirts.

Andreas, how did you get this so wrong? And if we cannot trust your history, why should we trust your politics?

[1] C.J. Bearman, ‘An Examination of Suffragette Violence’, English Historical Review, vol. cxx no 486, 2055, pp. 365-397 is the most detailed discussion of who did what, when and to whom. It is essential reading.

[2] The debate is between Jane Purvis, Elizabeth Crawford and Sandra Holton, ‘Did Militancy Help or Hinder the Granting of Women’s Suffrage in Britain?’, Women’s History Review, vol. 28 no. 3, 2019, pp. 200-234.

[3] P. Bartley, Emmeline Pankhurst, London: Routledge, 2002, p. 7.

[4] Sylvia later wrote ‘I believed then and always that the movement required, not more serious militancy by the few, but a stronger appeal to the great masses to join the struggle’. B.Winslow, Sylvia Pankhurst. Sexual Politics and Political Activism, London: Verso, 2021, p. 18.

[5] Winslow, op cit., p. 53.

[6] M. Pugh, The March of the Women. A Revisionist Analysis of the Campaign for Women’s Suffrage, Oxford: OUP, 2000.

[7] Bartley, op cit., p. 197.

[8] Bartley, op cit., p. 205.

[9] Bartley, op cit., p. 211.