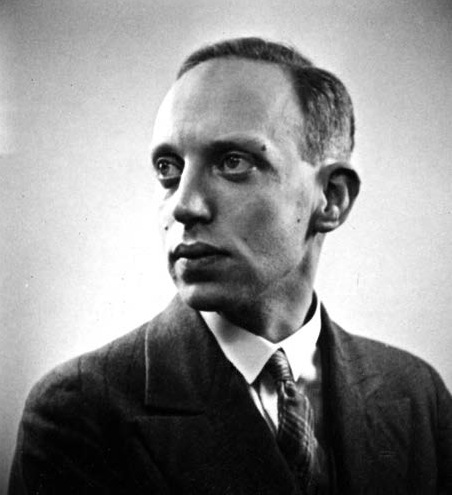

Richard Löwenthal (1908-1991) was a German Jewish writer and political scientist. In the Weimar Republic he belonged to the Communist youth movement and then to a revolutionary splinter group called the Leninist Organisation, also known as New Beginning. He helped organise underground resistance to the Nazi regime before he was forced into exile. He published a series of critical essays on fascism and Stalinism, which he interpreted as twin totalitarian efforts to repress class struggle. Eventually arriving in London, he aided the British war effort and helped broker peace between German Social Democrats and leftwing splinter groups in exile. After the war, he worked as a correspondent for Reuters and the Observer, covering developments in world communism. Eventually he resettled in West Germany, where he was named professor of political science at the Free University of Berlin. One of his students there was the New Left leader Rudi Dutschke. By the 1960s, however, Löwenthal had evolved from revolutionary socialist into defender of the democratic establishment.

The following essay appeared in September 1936. Under the pseudonym Paul Sering, the young Löwenthal formulated a critique of a new tendency among Central European Social Democrats called folk-socialism [Volkssozialismus], which was a form of left populism designed to win over supporters from the far right. The tendency emphasised national welfare, abandoned class struggle, and implicitly endorsed xenophobia. Löwenthal notes similarities between folk-socialism and the left wing of the Nazi Party around Otto Strasser. Whether left or right, he concludes, any populism framed in nationalist terms would benefit reactionary forces. This essay from the 1930s resonates with debates on the left today, which is grappling with how to combat the resurgent far right. Then and now, Marxists should resist the importation of ideas from the nationalist right as a dangerous form of völkisch socialism. There is a real socialist strategy for national leadership and international peace, and that strategy requires class struggle.

The first English version of this essay appeared as the pamphlet What Is Folksocialism?, translated in 1937 by Harriet Young and Mary Fox for the League for Industrial Democracy in New York. The original German version appeared under the title “Was ist der Volkssozialismus?” in the final issue of the Zeitschrift für Sozialismus in September 1936. It has been abridged and retranslated here for clarity. Please note that the German word Volk has a racial connotation that is lacking in the closest English equivalent, “the people”.

abridged translation by Terence Renaud

After a historic collapse and under uniquely difficult conditions, the German socialist workers’ movement is now trying to rebuild its organisations and redefine its tasks. In this critical situation, a tendency has emerged within the Social-Democratic parties of Germany and the German-speaking part of Czechoslovakia (Sudetenland) that claims to have figured out how socialists should reorient themselves. According to this tendency, workers’ socialism can only be resurrected as folk-socialism [Volkssozialismus]. The much-needed renewal of socialism consists not in redefining the tasks of the workers’ movement, but rather in recognising that the working class no longer has any special role to play. It is the duty of German socialists not to rebuild the workers’ movement, folk-socialists claim, but to join with the coming people’s movement [Volksbewegung].

Otto Strasser’s group of dissident Nazis is the prototype of this classless, folk-socialist movement. The folk-socialist current is thus one of conversion: it expresses the tendency by some members of the workers’ movement to convert to “leftwing” National Socialism.

Naturally, the sophistication and the degree of consciousness vary among representatives of this tendency. Folk-socialism is a kaleidoscopic ideology. It crops up in articles by the German Social Democrat Wilhelm Sollmann and in the book Folk and Workers (1936) by the Sudeten Social Democrat Wenzel Jaksch. The latter formulates it as a programme for converting working-class socialists. In his book Revolution of the West (1936), the former newspaper editor Emil Franzel makes a historical and philosophical argument for the complete abandonment of the worker’s movement.

We agree with folk-socialists that after the experiences of the last twenty years, a fundamental reorientation of European socialism is necessary. But we draw opposite conclusions from those experiences. We stand by our conviction that socialism in Germany can be achieved only under the leadership of an independent, unified, and tightly organised workers’ movement in alliance with all the forces of international socialism. We must therefore come to grips with folk-socialism as a forced entry into our ranks by an enemy ideology.

***

The system of parliamentary democracy, which the workers’ movement in many countries helped establish, has been in crisis in many countries since the shock of the Great War and the recent intensification of capitalist contradictions. The crisis of the state makes problems of power newly relevant. In one country after the next, an alternative has emerged between fascist state power and socialist state power. For the first time, the workers’ movement has the opportunity to secure the development of socialism by taking over the state. For the first time, too, it risks losing the democratic rights that it has already gained.

The course of the Russian Revolution offered the first sign of this new era. The victory of Italian Fascism was the second sign. These signs might be seen as resulting from a temporary postwar crisis and the particular fate of backward, agrarian countries. But that interpretation has been proven false since the Great Depression universalised the crisis of democracy. Moreover, the victory of fascism in Europe’s most industrially advanced country, Germany, has provided a third and unmistakable sign of our new era.

In the sixteen years between the Russian Revolution and the German catastrophe of 1933, the European workers’ movement has not adequately adjusted to its new tasks. This adjustment requires new forms of organisation and action, new leaders, and new personnel. For most of the workers’ movement, this renewal and redefinition of goals never took place. Nor has the workers’ movement realised that the power struggle is already underway. Until recently, people were faced with the alternative of organising as a parliamentary opposition or not participating in government at all. They were stuck in old forms of special-interest politics, and everything else they entrusted to an objective historical process that they refused to see was already in crisis. Even Communists, who under the influence of the Russian Revolution had split off from the mainstream workers’ movement, failed to achieve any real change of organisation and strategy.

A basic recognition of the need for a shift in strategy dawned at the onset of the Great Depression, and it has gained traction since 1933. Today socialists generally understand the need for socialist solutions and a coalitional policy based not on temporary electoral gains but on the permanent conquest of power: We aim for a total reconstruction of society.

Seizing power amid a crisis of democracy requires breaking the bonds of special interests, so that a workers’ party may legitimately claim leadership of the whole nation. Seizing power without the help of an agrarian revolution, such as what happened in Russia, requires new reflection on the political coalitions appropriate for each country. To destroy an advanced apparatus of oppression, and to take over a complex state administration and privatised economy, require careful technical and organisational preparation. The division of the European continent into hostile camps and the dangerous position of any isolated socialist government make it necessary to merge our various struggles into one general European fight for freedom.

***

The workers’ movement of the past era limited itself to special-interest politics, trusted in general social progress, and did not seize power. Folk-socialists blame this failure on the fact that it was a movement of one class only—the working class. They claim that a class-based movement is too narrow for socialist objectives and that Marxism, which bases socialism on the workers’ movement, is too limiting a doctrine.

In every country where democracy is in crisis, the class struggle indeed takes the form of a decisive battle for leadership of the nation. The party that wants to win must convince the whole nation that it is fit to lead, and it must have a clear position on all general national issues. Without a definite foreign policy, without combining that foreign policy with a position on national defence, and without integrating those issues into a day-to-day socialist agenda, there is no chance of taking and maintaining power. To demand this from a working-class party is not folk-socialistic. It is a realistic, socialist power politics. And it revives a Marxist tradition that was buried during a long period of reformist self-restraint. It would be folk-socialistic, however, to believe that the battle for national leadership will result in socialist victory without a ruthless class struggle.

The folk-socialists agree with both fascists and traditional reformists that proletarian class interests stand opposed to the national interest. That is because the fascists consciously and the reformists and folk-socialists unconsciously identify the national interest with capitalist growth. In capitalist class society, the advantage of one is necessarily the disadvantage of the other. Increases in wages will reduce profits and sharpen the general national crisis, which, in turn, drags down the middle class. We have often seen this happen. That is why fascists will demand and reformists will deliver the sacrifice of the working class to the national interest. That is why folk-socialists are clueless about the revolutionary possibilities of class struggle, and why the Belgian theorist Henri de Man believes that a socialist plan from above must replace economic struggle from below.

But the working class is strengthened by economic struggle, which, in turn, aggravates the crisis. Suppose it were to use that strength to strike a decisive blow against capitalist ownership? Suppose it were to prevent the capitalists from shifting the burden onto the middle class and, in alliance with the middle class, overthrow capitalist rule? Only then would a road to socialism open up for the nation, and only in that way could class interests and the national interest truly align. This is the Marxist idea of class struggle for leadership of the nation.

In Italy, the workers’ movement succumbed to fascism because it did not conduct its class struggle as a fight for political power, and because it aggravated the national crisis without offering a socialist solution. In Germany, the workers’ movement succumbed to fascism because it subordinated class struggle to the interests of the “people’s community” [Volksgemeinschaft], which, in reality, were the interests of the bourgeoisie. Thus, it crippled itself and was unable to seize power or implement any socialist solution. There were plenty of patriotic expressions by Social-Democratic and Communist workers in the last years before the Nazi coup, but this labour patriotism achieved nothing without class struggle. In France, the workers’ movement has proven over the past few months that proletarian class struggle and a successful alliance with the middle class are not opposed strategies, nor are fighting for better wages and fighting for the nation: these things belong together. The more resolutely this alliance defies big business, the stronger it is and the more entrenched its power in government. If such a government were to be diverted from its proletarian base by the alleged national interest, however, then it would soon lose the support of the middle class as well. The fight for the destiny of the nation must be conducted as a class struggle.

An antifascist foreign policy for maintaining peace must necessarily be coordinated between various countries. While the folk-socialists philosophise about the “reality” of the nation and the supposed impotence of internationalism, they overlook today’s actual foreign policy problems. While they set national politics against class politics, issues of foreign policy themselves take on a clear class character. Internationally, the creation of a strong antifascist front for peace depends today on the strength of the workers’ movement. The Labour and Socialist International will be effective as a real force precisely to the degree that the workers’ parties of each country succeed in their fight for control of the nation.

***

The main proponent of folk-socialism in the ranks of Social Democracy is Wenzel Jaksch. He invented the formula of reviving workers’ socialism as folk-socialism. His book Folk and Workers [Volk und Arbeiter] is, in many ways, a serious, positive contribution to clarifying the tasks of the German revolution. To secure socialist victory in Germany, he argues, the working class cannot be content with proclaiming its right to rule. It must prove itself capable of solving German problems in accordance with the needs of the vast labouring majority of people. Only then can it recruit this majority into a united socialist front. Insofar as the book formulates the issue in this way and contains concrete suggestions for solving that issue, we wholeheartedly agree with it.

Among other things, we disagree however with Jaksch’s take on foreign policy. At one point, he distinguishes between two kinds of national consciousness: the positive kind, which stresses the achievements of a nation and its tasks within the community of nations; and the negative kind, which manifests itself in nationalist defence against the surrounding world. In a similar sense, one can say that Jaksch himself begins with a positive national consciousness but ends up with a negative European consciousness. The latter starkly demarcates the Continent from all non-European peoples, from the British Empire, and even from the Soviet Union. This European nationalism expresses itself economically in his remarks about Continental farmers and textile workers. It expresses itself culturally in his emphatic resistance to Americanisation, about which he has only the vaguest notions. Likewise, he constantly emphasises the foreignness of Soviet Russia. Politically, this implies a tendency to want European unification as quickly as possible, regardless of the member states’ class character. Such a tendency privileges any European alliance, no matter what kind, over the possibility of closer ties with the Soviet Union.

If victorious only in one country, folk-socialists who strive for a European federation will nevertheless find themselves forced to defend against non-socialist states. In their hour of need, folk-socialists will have to rely on the Soviet Union. Being European nationalists, however, they reject any ties with the Soviets. So, they will seek nearby alliances no matter how reactionary those states are. To these alliances they will sacrifice whatever positive results their own socialist action may have produced. By maintaining the bourgeois character of the existing international order, folk-socialists will, despite their intentions, retain all of its internal contradictions.

***

The purpose of our analysis is to highlight the consequences of the folk-socialist attack on Marxism. Despite what they claim, folk-socialists are attacking not an obsolete Marxist terminology but, rather, the historic mission of the workers’ movement itself.

The impact of German fascism and the weakness of the workers’ movement in Central Europe caused this folk-socialist derailment. Those things account for why some people now believe that the answer to the new problems consists in tapping into fascism’s own sources of strength. Since Hitler won with the ideology of a socialism without class struggle, some think, socialism could win more easily with this same ideology. They treat the disappointed followers of Hitlerite ideology as forerunners of a new socialist idea.

The organised expression of the Nazi old guard’s disappointment is the “revolutionary National Socialism” of Otto Strasser. Folk-socialists in the Social Democratic camp who want to escape the constraints of Marxism advocate an alliance with Strasser. That also means assimilating his ideology. In fact, Strasser’s group represents the sort of “renewed” socialism that no longer proceeds from class interests, but, instead, bases itself on the situation of a proletarianised nation [Volk] and appeals directly to the soul of that nation. It meets all the demands that folk-socialists have made of the workers’ movement. Strasser’s group constitutes a model for their own development.

Strasser has recently published a new edition of his blueprint for German socialism (Aufbau des deutschen Sozialismus, originally 1931). The touchstone of his faction is its position on Hitler’s system. Now as before, he labels this system the “Gironde of the German revolution”. By analogy to the French Revolution and the Jacobins’ more moderate wing, Strasser thus interprets Hitler’s system as a stabilisation of the first, imperfect stage of the German revolution. Any stabilisation of an imperfect stage seems reactionary to him. But he fights Hitler’s system for the purpose of furthering its own ideals. Here lies his psychological and propagandistic advantage over supporters of Hitler’s existing system. But here also lies the principal weakness of his position: he cannot understand how a movement that shares his ideals could lead to such a desultory result.

Strasser has judged the Hitlerite movement not according to its social character but according to its ideas. On a series of important points, these ideas were actually his own: the overcoming of class struggle not through a genuine abolition of classes, but through a binding ideal; the decoupling of the socialist goal from the working class and its international organisation; and the treatment of war as the beginning of the German National Socialist revolution. He was and is of the opinion that the ideas of national solidarity, the sacrificial bond of all social groups, and camaraderie at the front are in themselves socialist. While he admits that these ideas must be realised in accordance with a socialist goal, he thinks that only Hitler’s shortcomings are to blame for the lack of any such realisation. According to him, Hitler’s ideology pollutes the “socialist” ideals of a “conservative revolution” with liberal imperialist race theory and a defence of private property. When Strasser realised that he could not change Hitler’s mind about these things, he broke with him in disappointment.He never learned the right lesson from his disillusionment with Hitler. The Nazi Party took its predestined path not because of Hitler’s stupidity, Goebbels’ mendacity, or Goering’s ambition. It merely obeyed the laws of the objective situation and the social forces involved. Strasser’s brother Gregor was defeated in the decisive party crisis of 1934 because he sought to build a coalition with trade unionists and somewhat progressive industrialists, not because of palace intrigues. Such a coalition would have contradicted the social nature of the Nazi Party, whereas his opponents oriented themselves toward the Party’s natural allies in the bankrupt Volksgemeinschaft. Hitler’s party failed to realise socialism not because it betrayed fascist ideals, but because it was, from the very beginning, a fascist party.

For Strasser, the real progress and partial success of Hitler consists in his having done away with bourgeois democracy. We Marxists do not want the return of the Weimar Republic either. If Strasser thinks that this system is historically obsolete, then he certainly has a greater sense of reality than some “constitutionalist poets” today. Just because the Hitler regime emerged more recently out of the unsustainable Weimar democracy, though, does not make it a better deal for socialists.

Parts of the workers’ movement were slow at first to acknowledge the stability of the fascist regime, so they predicted its collapse at every turn. Strasser has made this self-deception into his core principle. Whoever sees the regime as somehow incomplete or considers it an early stage of an ongoing revolution sustained by the same forces that started it, cannot grasp the fact that the regime has now stabilised. As a result of such misconceptions, some unusual ideas arise about how to overthrow it.

***

Strasser’s programme contains detailed specifications for building the state and economy in a manner that he considers socialist. He says absolutely nothing, however, about how to arrive at that socialist destination. We Marxists cannot afford to ignore this question, because folk-socialists in the Social-Democratic camp propose cooperating with Strasser on the road to socialism. Only the road and the destination together form a political programme.

According to Strasserite socialism, the ideal political form is corporate statism.[1] That involves a complex combination of local preliminary elections organised by vocation, indirect representation in the higher agencies, and appointment from the top down. In many respects, it is reminiscent of the structure of the Catholic Church. The details are irrelevant, but we will note two characteristics: first, the strict prohibition on political parties, justified by the need to vanquish “the obnoxious noble lie of popular self-government”; and second, the fact that Strasser’s system cannot be built from below but only from above. The three authoritative bodies that would govern his Reich are the President, the Great Council, and the Estates Chamber. Of them, only the third would result from an indirect vote. This system could begin to function only once the President is in place, appoints the ministers and regional presidents to the Great Council, and then—in a state without parties—announces elections by professional vocation (not by head).

When Strasser’s book first appeared, the clear assumption of his plan was that a faction led by him could seize dictatorial state power. Today, under existing fascism, the repetition of this plan and its anti-democratic polemic can only have one meaning. If things go according to Strasser, then Hitler’s system will be overthrown not by awakening the oppressed masses. Rather, it will take place as a revolution from above, a palace revolution within the Nazi machine, on the basis of which Strasser will bestow true socialism upon an amazed and delighted people!

Of course, Hitler will never be overthrown by a mere palace revolution. In that sense, Strasser’s corporatist fantasies pose no real danger to the regime. But, if the masses were to mobilise, then opposing factions would doubtless arise within the Nazi machine and try to use the masses as a means to their own particular ends. After the work was done, they would then restore the masses to their powerless condition. The duty of socialists, by contrast, will be to exploit the contradictions within the Nazi machine in order to empower a mass movement as the means to overthrow the regime. If socialists want this, they must not indulge in illusions about factions within the fascist machine itself. Socialists must oppose all ideologies that place the masses’ hopes in any reactionary faction.

***

On the issue of nationalism, Strasser has made the clearest and most positive progress beyond Hitler’s official doctrine. He conceives of the nation as a historical and cultural unit, not a biological one. He emphasizes that the value of each nation’s particular existence does not justify imperialism, but actually precludes it. On this basis, he promotes a federation of European nations on the Swiss model. A few pages after rejecting imperialism, of course, he is inconsistent enough to develop grand plans for a unified European colonial policy.

The crucial weakness of Strasser’s European design lies in the ambiguity of its domestic policies and the class assumptions of its implementation. Switzerland is no product of the twentieth century. Among advanced capitalist states beset by imperialist rivalries, a free federation is impossible. The only possible course of action in that situation is building a bloc of client states through victory of the strongest. Today, any free European federation would require the victory of socialism in all its member states, as the example of the Soviet Union shows. Socialists should strive for and promote such a federation, not apart from their other goals but together with a general programme of European socialism.

Strasser is unable to recognise this because he believes that every people must find its own social order, even if that order differs fundamentally from that of neighbouring peoples. For example, he suggests that the stability of Italian Fascism speaks to its suitability for the Italian people. But it is obviously impossible to build a free federation that includes a socialist Germany side by side with Fascist Italy and its vassals. Limiting socialist goals to one country thus becomes an obstacle to realising socialist goals for Europe in general. The road to a unified Europe is the same road to European socialism. It leads through the construction of a united front between socialist and progressive forces, not through a policy that tolerates European fascism.

***

The original mass basis of the Nazi Party extended far beyond the middle class. The Party’s policies were not determined by uniquely middle-class interests, although middle-class people ruined by the economic crisis did form its core. Its policies were those of all who could not hold onto their economic role amid the fierce capitalist competition and class struggle of bourgeois society. So, they were forced to call for help from a strong state in order to secure their own existence. This state has been established. It has eliminated democratic forms of class struggle. It has replaced liberal compromises with an activist economic policy, and today it confronts all social classes in the same manner: politically as oppressor, economically as sole customer, and administratively with an array of bureaucratic harassments.

In all classes, the regime has given rise to muffled discontent, a desire to be free from restraints, and a will to pursue one’s own interests freely again. Ideologically, this discontent takes a liberal form among the bourgeoisie and a socialist form among the workers. The middle class suffers most under the oppressive bureaucratic machine. Middle-class resistance will be partly religious or confessional and partly a variation on National-Socialist ideology itself. The Party’s disillusioned old guard are the spokesmen of middle-class resistance.

People in the middle class once believed that the power of a strong state could relieve the pressure exerted on them by competition with big business, technological progress, price fluctuations, and debt. Today, they see that large enterprises profit off of a booming economy, and that early attempts to curb technology have ceased under pressure from global competition and the needs of rearmament. They also see that debt relief continues only for those who are no longer creditworthy, and that the burden of price fluctuations due to market forces falls directly on them. The natural burdens of capitalist development now combine with the additional burden of a growing bureaucracy, which the middle class finds harder to bear than the bourgeoisie. A leitmotif runs through all the publications of the Strasser group. It stresses the dual fight against bureaucracy and for the autonomy of small producers.

Today, the entire development of productive technology and organisation tends toward a bureaucratic organisation of society as a whole, which, in one way or another, establishes itself in every form of government.

Individual countries perceive capitalism’s inherent and automatic tendency toward further technological development as pressure from the outside. Therefore, to defend against technological progress, the middle class demands protectionist autarchy. Autarchy within a national framework has proven impossible. Technological dynamism simply overrides it. So, educated people in the middle class extend their demand for autarchy to all of Europe. Their federation does not need to be socialist, because it has only one true aim: to protect the old Continental farmer and artisan’s venerable and complementary forms of production against the evils of global progress.

The Europe envisioned by folk-socialists is the nature reserve of the middle class. Strasser’s socialism is a craftsman’s paradise. Corporate statism is the reactionary utopia of reconciling each group’s ideal interests without resorting to raw forms of class struggle, which would mean a real reckoning of interests. Politically, Strasser believes that “the little man” who carried out the Nazi revolution will now take it “beyond Hitler” to its conclusion. The Germanic cultural ideal for which he strives is indeed to make all Germans middle class.[2]

Folk-socialism is a late form of middle-class socialism, siphoned off from the main flow into fascism. Folk-socialism in the Social-Democratic camp functions as a movement of ideological compromise with fascism in power, disguised as an adaptation to the needs of the present moment. Its drift toward Strasser owes not to Strasser’s own allure but to the real strength of Hitler. Insofar as they borrow their ideology from Strasser, the folk-socialists seek to renew socialism from the same sources out of which fascism drew its strength. But socialism can only renew itself by returning to its own sources of strength.

***

Emil Franzel’s book Revolution of the West can be viewed as the quintessential philosophy of history for all shades of folk-socialism. From its vantage point, one can supposedly reach new value judgements and a new groundwork for the socialist idea.

The socialist ideal that Franzel sees first embodied in the Middle Ages is the meaningful incorporation of each person’s work into the work of the community as a whole. All socialists undoubtedly have this goal in common. But Franzel separates the realisation of the socialist ideal from the productive forces and class structure of existing society. Thus, while he does not wish to revert entirely to the medieval stage of technology, he is always ready to pay the price of technological regression in exchange for a close-knit, static, and de-proletarianised society.

For us Marxists, socialism means abolishing the division of society into classes of exploiters and the exploited. Socialists seek to create the preconditions for a society in which all of humanity can exist humanely and flourish. We cannot arrive at these goals independent of technology. That there are today not only socialist ideals but possibilities for their realisation owes precisely to the fact that humans’ productive capacities have reached a stage at which socialist ideals can actually be achieved.

Thus, socialists cannot share Franzel’s negative attitude toward technological progress. As certainly as capitalism has brought us nearer to the possibility of socialism, it has brought us tremendous progress in social organisation. Insofar as the liberal ideology of ascendant capitalism celebrates these forward steps, we agree with it. It is true that technological progress has made it possible to support more people with less work, and to satisfy their demands more abundantly than ever before. But socialists have never shared the liberal illusion that these blessings of technological progress are automatically realised under capitalist conditions. They have always pointed out that the inevitable result of those conditions are economic crises and mass unemployment. For the masses, capitalism guarantees only misery, not upward mobility.

That does not prevent socialists from welcoming the development of productive possibilities as such. Whoever adopts Franzel’s backward stance on technology denies the real potentialities of socialism. He posits the fictitious ability of a close-knit social order to sustain fragmented, small-scale production. In response to our existing society that suffers from an inability to fully utilise its wealth, he preaches the ideal of poverty rather than the rational utilisation of wealth.

Just as Franzel does not understand the importance of industrial development for socialism, so he sets historical tasks for the proletariat that fail to overcome the proletarian condition itself. The working class is, for him, only a symptom of capitalist misery and not also the post-capitalist vanguard. As a result, he adopts the Nazi term de-proletarianisation [Entproletarisierung]. He does not say how he imagines it playing out. One can only guess based on his general agreement with other folk-socialists.

We can overcome the proletarian condition only by organising large-scale production, not by changing proletarians back into small-scale proprietors. The revolution can consist only in proletarians establishing and actively supporting a society that takes control over production and makes workers jointly responsible for production. Absent capitalist crises and mass unemployment, precarity will cease. And through the creation of developmental opportunities for each person on the basis of growing social wealth and the elimination of parasitic classes, work will cease to function as a marker of class identity. Overcoming the proletarian condition therefore lies in the abolition of wage labour. It means transforming labourers into joint owners of organised general production, not into small-scale proprietors. It remains crucial that the active supporters of the new society of tomorrow are chiefly the proletariat of today.

But the word de-proletarianisation indeed has a definite cultural meaning for Franzel, even if it lacks any definite political or economic meaning. For him, it really all comes down to cultural values—even aesthetic values, in the narrowest sense. His real quarrel is not with capitalism, but with the crude culture produced for mass consumption. His real heroes are not the militants of the socialist workers’ movement, but the artistic loners who form a small elite within and against today’s cultural chaos. Too bad for him that the aristocrats of the spirit on whom he calls, whether they are named Stefan George or Karl Kraus, have never had anything to do with the socialist cause.

It is here that Franzel’s criteria for reinterpreting history and remodelling socialism come into focus. It is here that this folk-socialist gets exposed as an anti-proletarian socialist.

The folk-socialist may be well educated, even in Marxism. He can argue along Marxist lines that the proletariat, which inhabits a bourgeois world and whose ideas derive from that world, cannot generate the values required for a socialist culture. But he offers no argument besides his hunch that the future socialist world is embodied already in today’s aesthetic-aristocratic outsiders. Even if it is impossible to prefigure socialist culture, particular values do arise from the conditions of the socialist struggle, a struggle which the proletarian masses are waging. Here we find the true spirit of solidarity in its contemporary guise; here we sense a will to freedom that is no longer merely “liberal”; here we witness the fight for human emancipation as it really takes place. Socialism will not be brought about by artistic loners who somehow de-proletarianise the world. The proletariat will transform itself by transforming society.

The task of fighting for socialism does not belong to the working class alone. The most conscious and active socialists from all classes may join the socialist movement. But the movement’s main force must be the working class. In its fight, it needs not only allies but also intellectual experts of all sorts in its ranks. It needs them to help realise its role as leader of the socialist movement. But it does not need intellectuals who deny that role.

***

The chief characteristic of the European situation today is the conspicuous trend toward the development of international class fronts.

With growing clarity despite internal divisions, the forces of the workers’ movement are coalescing in a defensive front for peace and democracy: this is the front of the Soviet Union and its democratic allies. It works to give all members a uniformly antifascist character, which will consolidate the front and make it the rallying point for progressive forces in all countries.

Likewise, the forces of European reaction coalesce in the camp of German fascism. Already we have witnessed a proposed alliance between the Catholic Church and Hitler against Bolshevism, and already we have seen tendencies toward a Central European bloc of dictatorships. This is the international reactionary axis that unleashed the Spanish Civil War and supports the Nationalist rebels. In every country, this is the axis that wages a war of annihilation against socialist forces.

It is good to speak about European unity in this situation and proclaim it as a goal. But it is crazy and dangerous to promote the illusion that this unity can be salvaged through rapprochement between the two hostile fronts. A peaceful settlement of differences is out of the question. With fascism there is only one form of appeasement, and that is capitulation.

[1] That is, a Ständestaat or estates-based system modeled on the feudal old regime.

[2] For a depiction of this endangered middle-class mentality and its susceptibility to fascism, see Hans Fallada’s 1932 novel Little Man, What Now?