In the 1890s, the idea of a “record industry” was a novel concept. The phonograph had only been invented in 1877, its close cousin the gramophone patented and made available for purchase little more than a decade later. The notion that you could hear a sound at a time other than when it was being created? Until recently, this had been beyond the pale of possibility, akin to the first decades of the photograph, just starting to shift the sonic and cultural contours of daily life.

Emile Berliner, the German-born American businessman who first marketed the gramophone, guessed that there was a new market emerging. He was right. Yes, he had the capital to make that market viable, but so did people’s response to the remarkable new direction in the medium of sound. Berliner was there to capture it. First came the United States Gramophone Company in 1894. Four years later, it was the Gramophone Company in England and Deutsche Gramophon in Germany. This was a new industry, but a thriving one.

By 1917, however, these European iterations of the record industry barely existed. Berliner had been unable to keep operating Deutsche Gramophon after the onset of World War I. Its Russian operations had been seized by the revolution. And the original Gramophone Company factories in Middlesex had been converted to manufacture munitions for the British war effort. Apparently, the precision needed to build machines capable of reproducing sound could be easily repurposed to make casings for the artillery shells blowing apart young men on the Western Front. An industry is an industry.

Skip forward, through the various imbrications of the record industry and the war industry: through the invention of headphones by the American military during World War II, to the Gramophone Company’s inheritor label EMI’s involvement in developing cruise missiles, to Spotify co-founder Daniel Ek’s $700 million investment in AI-operated military drones. Ek has been involved in German weapons tech developer Helsing for years, but it was this massive investment that started to catch Spotify flak in the summer of 2025. Several artists – Deerhoof, Xiu Xiu, Godspeed You! Black Emperor and many more – very publicly removed their music from the streaming platform.

This was the latest in several waves of bad publicity. Spotify is notorious for paying artists fractions of a penny per stream as it rakes in billions, a fact about which artists have been increasingly vocal. The streaming giant’s own use and allowance of artificial intelligence has been a growing bone of contention. This came to a head around the same time news of Ek’s Helsing investments broke, when “Velvet Sundown” – a band entirely AI-generated; music, promo photos, and backstory – gained more than 1 million streams. Though Spotify itself had no direct connection to the “art hoax”, it highlighted how easy the platform had made it to rip off and even entirely displace genuine artists.

For many artists, living as they do in the context of not just economic precarity but of an interminable war in Ukraine and a full-on genocide in Gaza, the Spotify-Helsing news was simply the final straw. That their music might become another cog in the literal war machine was deeply disturbing.

“There must be hundreds of bands right now at least as big as ours who are thinking of leaving”, Deerhoof’s Greg Saunier told the Los Angeles Times. “I thought we’d be fools not to leave, the risk would be in staying. How can you generate good feelings between fans when musical success is intimately associated with AI drones going around the globe murdering people?”

As a result, Spotify’s public relations department has spent the last half of 2025 in damage control. The Velvet Sundown fiasco is almost certainly behind the decision to scrub 75 million AI-generated songs from the service, though it hasn’t stopped tens of thousands of other AI tracks from being uploaded each day. Whether the Helsing fallout led directly to Ek stepping down as CEO (though remaining as Executive Chairman) hasn’t been stated, though the timing is notable.

Spectacular sound

Pulling back our focus, Spotify’s recent troubles can be seen as the latest episode in a generalised crisis for significant sections of the culture industry. Streaming platforms have a notoriously difficult time turning a profit when it comes to film and television. Subscription numbers simply aren’t enough; most services are kept afloat through venture capital. The resulting downward pressure on actors, writers, and crew has already produced large-scale rebellions among artists in the form of the prolonged Hollywood strikes of 2023.

Spotify, conversely, has to shell out very little in terms of production or release costs. Combine this with paying artists an average of $0.003 per play, and it’s easy to see how a large base of premium subscribers can garner the kind of profit it has. Where Spotify’s own crisis manifests is in what it must do in order to keep ears hooked to its services. Its algorithms have already become notorious for favouring some artists over others, and the competition for artists to get onto one of the services coveted playlists have resulted in a well-documented narrowing of sonic diversity.

That streaming platforms view musicians less as artists and more as “content producers” feeds into a sharpening of alienation between these artists and their art. It is therefore appropriate to draw a link between the problems of profitability in the culture industry and the broader contemporary “crisis of believability”, feeding back into the progressive erosion of social cohesion.

It is also apropos to view this crisis through the lens of the spectacle, as it has been understood and argued by the situationists: a recuperation of artistic expression’s vaunted freedoms back into modes of commodification. That a significant step in this process is the transformation of art into a material support for the weapons of modern warfare should be unsurprising, given how much discourse and media chatter is shaped to normalise daily dispossession and outright slaughter. “Everything that appears is good”, wrote Guy Debord, “whatever is good will appear”. Even if what appears is mass death.

“There’s certainly a link”, says Joey La Neve DeFrancesco, guitarist for the Downtown Boys and founding member of United Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW).

These tech CEOs, their interests are of course profits above everything. I’m not sure if Daniel Ek was more of a music fan that he wouldn’t operate this way, given the incentives of running a company with a monopoly like Spotify. That’s what capitalism does. But certainly this ‘tech guy’ ideology taking over everything is accelerating that and contributing to this. They truly, truly do not care. We used to see, across the tech industry, some veneer of liberalism, wanting to seem like they cared about music and the arts and peace and love. Now they’ve totally stripped away that veneer, wholeheartedly embracing Trump and the weapons industry.

Though Big Tech’s liberalism may have given way to a plainer ruthlessness, what remains constant is the denial of the massive amounts of labour going into it, compensated with pennies if at all. It’s there in the data we provide through mobile devices, in the hyper-exploited microworkers training the algorithms, and in the paltry compensation of artists on streaming platforms.

The time and effort required to write a song or record an album is almost entirely elided by the ease and access of streaming. If the virtual entirety of recorded music is instantly available at our fingertips, the implied logic goes, then it can’t really be work. Except that it is, of course. Literally everything required for something like leisure time to exist also required someone making it. And the very idea of leisure time, as something distinct from work, is only possible if it can be comfortably situated in a system that appropriates the fruits of surplus labour into the hands of a few.

The times and places where one “gets to exist” are only allowed in the shadow of the times and places where work is performed and labour is extracted. By now, pointing this out is to illustrate what most instinctually know. As for work being “robbed of its charm”, it feels positively quaint by today’s standards. If artistic expression, long portrayed as a realm of life somehow beyond the logic of work, can have the actual circumstances of its production be so atomised and reified, then it says something about the reality of what Jodi Dean has famously called “communicative capitalism”, particularly as late capitalism moves out of its liberal phase.

Dean’s formulation – now well-known and frequently referenced on the Left – posits that the digitally networked world radically reconfigures our sense of boundary between fantasy and the Real (per Lacan) and of what it means to actively participate in society at large, resulting in an ontology where virtually anyone can be transformed into an other, a “threat to be destroyed”. It’s an argument Dean has been making for twenty years, though its implications have become more and more apparent, and have been codified in subsequent formulations such as Nick Srnicek’s “platform capitalism”.

In any case, the outcomes are spectacularly grim. In his new book Why Sound Matters, musician and broadcaster Damon Krukowski writes about the recent trend of audience members throwing hard or sharp projectiles at performing musicians – of whose music these audience members are supposedly a fan. These incidents occasionally lead to serious injury among performers. Krukowski suggests that the phenomenon may have something to do with how streaming renders the performer “unreal”, obscuring their labour and subjectivity, denying the consequentiality of harming them. If this correlation holds, then it can feasibly be framed as a logical evolution of communicative capitalism into a version of itself befitting the post-liberal age.

The work of art (and music) in the age of algorithmic reproduction

The denial that art is labour and the insistence on sound as commodity are, like so much else under late capitalism, an irreconcilable contradiction. Streaming has already reconfigured the relationship between artist and their art and their audience. It is not hyperbole to say that the next step is, if some executives have their druthers, the virtual elimination of the artist. Is that possible? Even something as mundane and anodyne as relaxing nature sounds require someone to record them. Spotify, however, floods its service with these kinds of tracks – many of which Spotify claims to “own” – as a way to pitch its app as necessary for general wellbeing.

Leaving aside the specious and downright dicey notions that come part and parcel with the very concept of “wellness” and the industry that has sprung up around it, the amount of estimated revenue generated by this kind of practice generates a wholesale windfall for Spotify. According to Krukowski, every day an estimated 3 million hours is spent listening to these “white noise” tracks, generating an estimated $38 million in yearly profit. On the grounds that “nobody can own the wind”, few if any of those who recorded these sounds receive even the pittance thrown to the songwriters and musicians.

Plenty has been written about it, but the advent of AI accelerates this trend of “removing the human” as much as possible, particularly in the arts. The same goes well beyond the boundaries of the culture industry. AI could signal a historic freedom of humans from drudgery, but that’s not the case. If anything, the age of AI is coming to view all humans as liabilities, save for those who own and design the technology. To many, Velvet Sundown’s “success” felt less like a shock and more like a rueful confirmation. “The machines make ‘paintings,’” writes Adam Turl in their book Gothic Capitalism: Art Exiled from Heaven and Earth. “You work at UPS. The machines write poetry. You work at Starbucks”.

In the face of this, campaigns by musicians for fair pay are about more than compensation. They are about the artists’ continued control over what they produce as a unique creation, and the persistence of artistic autonomy as a viable facet of daily life. It may be telling that many of the artists involved in the most recent spate of boycotts are on the more experimental, unconventional ends of the musical spectrum. However much one might enjoy the music of Xiu Xiu or Godspeed You! Black Emperor, their music is difficult to mimic through the formulae of AI.

Or rather, it is for the time being, while AI is still slow to learn or understand these artists’ sound. As time progresses, and even as AI continues to gorge on its own enshittified information, the space for fringe expressions – in music, visual art, literature and more – tightens. The prospects of an avant-garde, long beleaguered under neoliberalism, have always been threatened by capitalism’s drive to automate. If we so rarely hear from or even think of the avant-garde today, this is no doubt a significant reason.

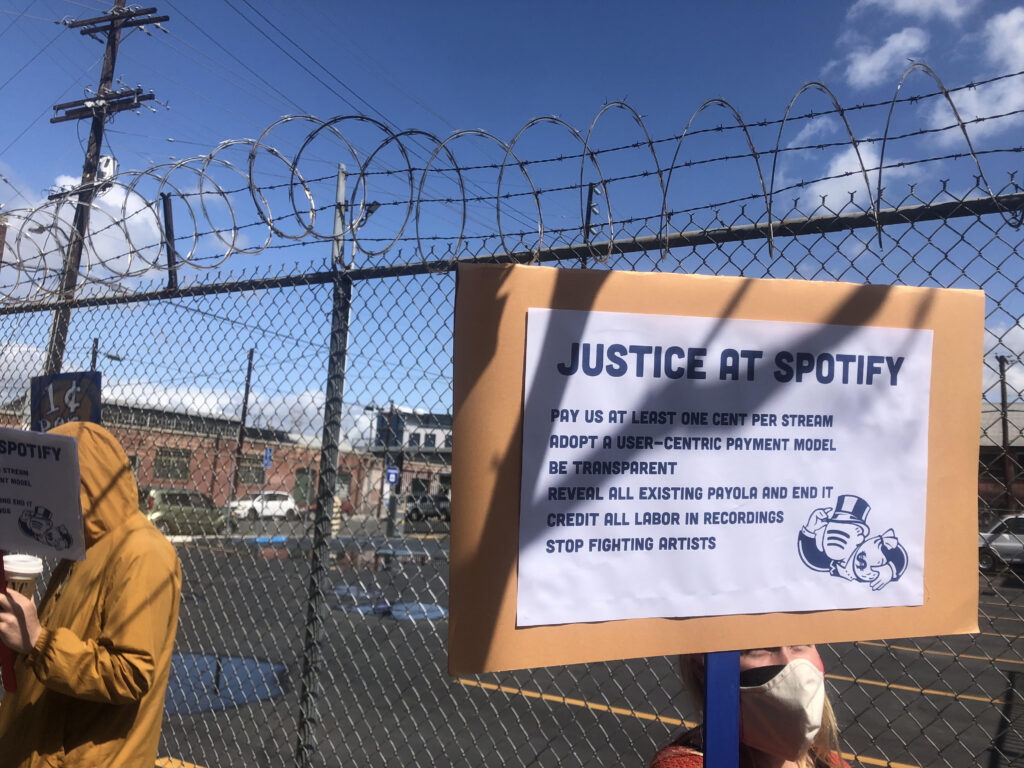

UMAW came together in the United States during the height of the Covid pandemic. With the shutdown of public life making live, in-person performance impossible, touring artists were left without an income and unable to ignore the dismal compensation. Since then, it has grown into something like a trade union, insofar as one can exist in the unstable world of recording artists. Its largest campaign has, predictably, attempted to force Spotify to pay artists the whopping sum of a penny per play.

UMAW isn’t calling for a boycott of Spotify in response to Ek’s Helsing ties, though DeFrancesco points out that they’ve been supportive of musicians who have decided to remove their material from the streamer. “Artists are pulling their music off. There’s absolutely no criticism of that”, he says. “We see our role as trying to more systemically take on the streaming industry”.

From alienation to exterminism

Taking on streaming presents very real challenges that cannot be ignored. Viewing it as peripheral would be a mistake. So too would dismissing the organisation of musicians and artists against it as somehow epiphenomenal to the class struggle. True, organising musicians comes with peculiar challenges. Much as streaming services rely on their labour, they aren’t placed in relation to each other in precisely the same way as a more “traditional” workplace. It is difficult, for instance, to imagine musicians going on strike against Spotify.

However, in the age of fully integrated communicative/platform capitalism, when companies like Google and Amazon have radically reconstituted both the labour-capital relationship and everyday subjectivity, these kinds of casualisation and atomisation are commonplace. The daily existence of autoworkers, janitors, teachers and cubicle drones are increasingly enmeshed with that of Uber drivers and Mechanical Turks that populate the automated gig economy, particularly as its models are brought to bear on other industries.

As such, streaming platforms’ enthusiasm for AI is a bellwether. Not only does AI’s isolation and atomisation of the labour process bode horribly for the future of the fully realised human subject, the technology is already doing more than its part to render the planet uninhabitable. Artificial intelligence requires a mammoth volume of clean water to cool the servers necessary for its operation – some estimates put it at two litres per kilowatt hour. According to University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, AI could be consuming approximately 6.6 billion cubic meters of water per year by 2027, and at a time when more than a billion people lack access to clean drinking water.

E.P. Thompson had a word for this approach to the designs of everyday life: exterminism. The outlook he identified in relation to the Cold War’s nuclear arms race finds strong echoes today in luxury doomsday bunkers, securitised gated communities, armed guards trained to keep the inconvenient hordes out (just in case the drones malfunction). In his book Four Futures, Peter Frase calls these “inverted gulags”, designed to repress and disenfranchise by locking out rather than in.

Four Futures deftly updates Thompson’s concept by bringing it into the age of climate catastrophe and full-scale automation. Though it was released almost a decade before ChatGPT became a household word, Frase’s descriptions hold true. If anything, AI makes them more prescient:

The great danger posed by the automation of production, in the context of a world of hierarchy and scarce resources, is that it makes the great mass of people superfluous from the standpoint of the ruling elite. This is in contrast to capitalism, where the antagonism between capital and labor was characterized by both a clash of interests and a relationship of mutual dependence…

So, it is embodied in the logic of the AI weapons drone. It is not known whether Daniel Ek has his own doomsday bunker, though he can certainly afford it. Nevertheless, his investment in the very possibility of war waged by robots reflects, at minimum, a partial acceptance of apocalypse as inevitability, and the need to eliminate the contingency of human choice-making from the equations of warfare. In the past, the weakness of most war-making was the ability of a soldier to put down their weapon, to refuse to shoot another like them. Bertolt Brecht once wrote that even the most powerful and destructive tank still has one defect: “It needs a driver”. It doesn’t anymore, at least not like it once did.

The elimination of contingency and subjectivity is, in fact, something that streaming is well-suited for, particularly as public space has shrunk, atrophied, or disappeared altogether. The portable sonic architecture provided by an algorithm or AI that “knows” what you want to hear next further mitigates against chance or encounter. It imbues passivity rather than initiative and entrenches the idea that those existing outside the sonic bubble are at best an obstacle, at worst disposable.

Might it be a bit dramatic to draw a straight line from Spotify’s denigration of music to hackneyed, full-scale cyberpunk dystopia? Perhaps. Then again, reports of Ek and his AI weapons drones came alongside growing concerns regarding the complete collapse of the North Atlantic air current. Cue increased catastrophic heatwaves, freezes across much of Europe, droughts, and crop failures.

The telos of a vast scorched, wasted world pockmarked with a few oases of automated luxury is in keeping with a historical trajectory Spotify already tacitly accepts: from the division and atomisation of labour, to the isolation of the artist in the name of art’s commodification, up to and including rendering them disposable, through to the neutralisation and finally the disposability of the masses themselves to maintain profitability, the plunder of resources be damned. That such a world would be unsustainable, inevitably buckling in on itself, is beside the point. It is a scenario for which many of the richest are already preparing.

The elimination of contingency and subjectivity is, in fact, something that streaming is well-suited for, particularly as public space has shrunk, atrophied, or disappeared altogether. The portable sonic architecture provided by an algorithm or AI that “knows” what you want to hear next further mitigates against chance or encounter. It imbues passivity rather than initiative, and entrenches the idea that those existing outside the sonic bubble are at best an obstacle, at worst disposable.

Despite all this, it is worth considering how none of it was inevitable. Just as AI might have helped simplify and liberate people from a large portion of daily work, the technological skill that made recorded music possible could have been, per Benjamin, a cypher for art’s radical democratisation. It need not have been diverted into the manufacture of arms or built on the backs of untold amounts of sweat and creativity. It is as true for Spotify and Helsing as it was for the munitions made at the Gramophone Company.

Sound and silence, repression and resistance

All of this exists alongside what may be the most overt state crackdown on anti-war artists in more than a generation. Belfast hip-hop group Kneecap have had charges of supporting terrorism dropped in the UK courts, but they are still banned from travelling in the United States. Same with Bob Vylan after their provocative statements from the stage at Glastonbury. And while the mass slaughter in Gaza has mostly ceased (for now), one wonders what other consequences there will be for artists and musicians who continue to speak in support of Palestine. That a certain Palestinian solidarity group remains proscribed by the UK government, that students and organisers in the US still face punishments including expulsions, firings, and even deportations, gives us some sense. What Herbert Marcuse identified several decades ago as “repressive tolerance”, liberal capitalism’s smothering of vital speech with endless choice, is now giving way to straightforward repression (though still, perversely, in the name of protecting freedom of speech).

Even so, it seems artists’ revulsion at being complicit in the war machine has reached a significant point, forcing them to reassess their conclusions about the broader structures of the culture and tech industries, and how artists are situated within it. Take, for example, Brian Eno. The prodigal innovator of modern ambient has long been a vocal supporter of Palestine, and he was one of the prime organisers for September’s “Together for Palestine” concert at Wembley Arena.

Eno has been around for decades, and is certainly no stranger to the shady machinations of the music business or capitalism. Still, this past May, he was moved to speak about the unique role he played in relation to Microsoft – also complicit in providing Israel’s Ministry of Defense with military AI:

In the mid-1990s, I was asked to compose a short piece of music for Microsoft’s Windows 95 operating system. Millions – possibly even billions – of people have since heard that short start-up chime—which represented a gateway to a promising technological future. I gladly took on the project as a creative challenge and enjoyed the interaction with my contacts at the company. I never would have believed that the same company could one day be implicated in the machinery of oppression and war.

That seven second opening chime is iconic, synonymous with Microsoft itself and the era that made the home computer a truly everyday item. But this “promising technological future” came hand-in-hand with the further privatisation of life at the apex of neoliberalism, a key step in the present and future decimation of the commons. Again, considering the potentials both the computer and the internet represented for a radical democratic access to information and education, it needn’t have turned out this way.

In his statement, Eno also pledged to donate the fee he received to foundations aiding victims of Israel’s bombardment. He has long been among the many artists who support the cultural boycott of Israel (a list that has grown since the beginning of its most recent bombardment), a critic of prevailing streaming models, and of the industry’s obsession with slick, over-perfect production. Adding it all together, it would seem that Eno’s vision of a truly democratic music industry would be one that values chance, contingency, surprise, encounter, and the labour that produces them.

Threads of this vision can be found in any effective strategy for taking on the streaming companies and the culture industry as a whole. The separation of music from the war machine is deeply intertwined with the right of artists to a decent living, which itself cannot be meaningfully accomplished without providing that right for all labour. In turn, none can be realised without a thorough reimagining of society’s shape and, ultimately, the return of a flourishing commons.

Bring it back down to brass tacks. As Joey DeFrancesco points out, the more money streamers are obligated to pay artists, the less there is to develop weapons with. UMAW has already been at least partially successful in this regard, campaigning alongside Palestinian solidarity groups to have weapons contractors like Raytheon and Collins Aerospace booted from SXSW in Austin, Texas. Across the Atlantic, similar boycott campaigns have managed to get Barclays Bank – also deeply invested in the arms industry – to withdraw from sponsorship of several festivals.

“This was huge”, said DeFrancesco about the SXSW victory. “As far as we know, this kind of thing has never happened at a music festival before. I think it presented an interesting way we can have entertainment labor both advocate for better conditions and for more ethical practices in the industry”.

It’s one thing to win this in the context of music festivals. To pull it off with the most hegemonic music streamer in the world, the service that virtually everyone carries with them on their phone without a second thought? That would likely imply a broader, more radical reshaping of the music industry, prioritising music and artists – and human beings – over all the venal ruthlessness that views everything around it as something to be either sold or eliminated, and in turn the aforementioned reshaping of everyday life. It sounds utopian. It sounds a bit unhinged. It also sounds, and is, necessary.

Alexander Billet is a writer and critic based in Los Angeles. He is the author of Shake the City: Experiments In Space and Time, Music and Crisis (second edition forthcoming in 2026), and has contributed to Los Angeles Review of Books, Salvage, Jacobin, Protean, and other outlets. Read more of his work at alexanderbillet.com.