Bruno Leipold’s Citizen Marx: Republicanism and the Formation of Karl Marx’s Social and Political Thought and Vanessa Will’s Marx’s Ethical Vision

Introduction

With his development this realm of physical necessity expands as a result of his wants; but, at the same time, the forces of production which satisfy these wants also increase. Freedom in this field can only consist in socialised man, the associated producers, rationally regulating their interchange with Nature, bringing it under their common control, instead of being ruled by it as by the blind forces of Nature; and achieving this with the least expenditure of energy and under conditions most favourable to, and worthy of, their human nature. But it nonetheless still remains a realm of necessity. Beyond it begins that development of human powers which is an end in itself, the true realm of freedom, which, however, can blossom forth only with this realm of necessity as its basis.[1]

Marx, Capital, Volume Three

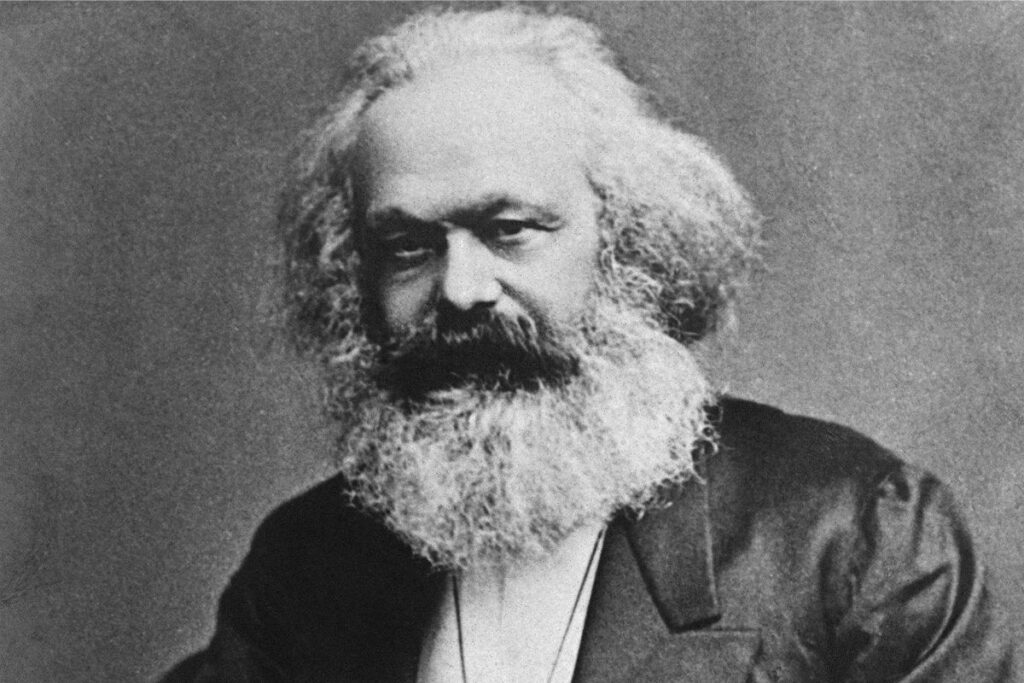

In the “Theses on Feuerbach” Marx declared that philosophers had hitherto only interpreted the world when the point was to change it. And change it he surely did. If Plato is the quintessential tragic philosopher who sought to in vain to influence the world, Marx lies on the opposing pole as the tragic thinker whose thinking influenced enormous upheavals, many of which Marx would have viewed with contempt, repeating his classic line that ‘if they are Marxist then I myself am not a Marxist’. The index of figures and movements he inspired is as astonishing as it can be disturbing. Marx inspired authoritarian movements and labour activism, democratic-socialist efforts to impose limits on the working day and dense cultural theories about the nature of our postmodern condition. The world-historical changes Marx provoked makes interpreting him a challenge in the 21st century. Familiarity with what one has heard about Marx, or thinks one knows, often takes the place of real analysis. There have been so many takes on Marx and Marxism, a lot of almost purposively low quality, that it can be hard to look at his work itself with eyes unclouded by Prager U or Rupert Murdoch’s The Sun.

This is a shame, since there is still much we have to learn from Marx in a century where however things change, much remains the same. It is now easier to imagine the end of liberalism than the end of capitalism. Indeed, capitalist realism seems stronger than ever, as America is set to be governed by a cabal of billionaires who promise to stick it to liberal elites by ending wokeness, even as they drool at the prospect of gutting already threadbare government services providing a safety net for everyone else. If this stirs one’s sense of injustice, that is a healthy sign that change may still be possible. Understandable pessimism of the intellect should never be an excuse to indulge in pessimism of the will.

Marxism’s disinterest in justice

For some readers, referring to “injustice” in an essay on Marx may be a big red flag. After all is not Marx the quintessential “materialist” thinker who held questions of right and wrong, justice and injustice in contempt? Did he not chastise the utopian socialists for their abstract fascination with blueprints and questions of “right”, caricaturing them as writing recipe books for the cook shops of the future? This longstanding view had deep resonance through 20th century Marxism. Many agreed with Althusser’s argument that the young Marx may have dabbled in making moral arguments here and there. But these pre-Marxist positions were largely superseded by the mature Marx’s transition to writing about the science of history and society without the need to recourse to moralism.[2] In Self-Ownership, Freedom and Equality, the analytical Marxist G.A. Cohen summarised this outlook with his patented clarity:

Classical Marxism distinguished itself from what it regarded as the socialism of dreams by declaring a commitment to hard-headed historical and economic analysis: it was proud of what it considered to be the stoutly factual character of its central claims. The title of Engels’ book, The Development of Socialism from Utopia the Science, articulates this piece of Marxist self-interpretation. Socialism, once raised aloft by airy ideals, would henceforth rest on a firm foundation of fact.[3]

On this “classical” view, there was, in fact, no reason for Marxists to talk about justice, morality, or ethics. Instead, what was required was a hardheaded application of Marx’s method to empirical material, which would, of course, demonstrate how the latent contradictions of capitalism inevitably paved the way for the emergence of a higher form of society.

As Cohen points out, the fall of the Soviet Union seriously challenged many of these views. Even though it, in fact, vindicated Marx’s insistence that building socialism in a country where material conditions were not right was doomed to failure, the moral and political failings of the authoritarian command economies were too blatant for any but the most dogged to retain faith in the inexorability of a historical transition to socialism. Moreover, Cohen notes it was always something of a self-conceit that Marxists were indifferent to moral principles. It was always “in part bravado. For values of equality, community and human self-realization were undoubtedly integral to the Marxist belief structure. All classical Marxists believed in some kind of equality, even if many would have refused to acknowledge that they believed in it and none, perhaps, could have stated precisely what principle of equality he believed in.”[4]

Marx the republican

Cohen is absolutely right that the disavowal of Marxism’s moral impetus has always been a weak spot in the tradition. It has made it much more difficult to render explicit the core principles Marx stood for, which, in turn, obscures the longstanding debate about what a just and workable postcapitalist society might look like. Fortunately, recent Marxist scholarship has done a lot to try and explicate the core moral principles that should define anticapitalism. Much of this builds on pioneering late-20th century efforts by authors like Cohen, Rodney Peffer, and Allen Wood to open the blinds on this intriguing horizon.

Two recent books in this genre are Bruno Leipold’s Citizen Marx: Republicanism and the Formation of Karl Marx’s Social and Political Thought and Vanessa Wills’s Marx’s Ethical Vision. As their titles suggest, the books tackle different sides of Marx’s normative outlook. Leipold is interested in Marx’s republican concern for a society free of domination and focuses on the social and political sides to his œuvre. Wills is concerned with the core of Marx’s “ethical vision”, where the key influences and competitors are figures like Aristotle, Kant, Hegel and J.S. Mill. However, the books complement one another in laying out the vision Marx had for a future socialist society: radically democratic political and economic institutions to protect against domination, highly equal but not crudely egalitarian in calling for something like equality of outcome, and focused on the cooperative development of human powers.

Leipold’s lucid and extraordinarily erudite book is the more straightforward of the two. He is deeply inspired by the recent “republican” reading of Marx defended by William Clare Roberts.[5] Republican thinkers hold that a narrow version of classical liberalism does not have a monopoly on theorising freedom. They emphasise that to be free is not just to be left alone by the state or others in certain prescribed domains of life such as the market or the private sphere. If one lacks other rights and powers, for instance to a say in how one is governed by the state or in the workplace, one can be very much unfree because you’re subjected to the exercise of arbitrary power.

A classic example is of the slave who is kindly treated by his master, left largely to his own devices, and even paid a salary. While such a person seems “free”, in the sense of largely being left alone, they are still subject to domination and subordination by a master who can withdraw that freedom at any time. The drafters of the Declaration of Independence intimated just as much when they that equal men have a right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” but that to “secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” It is not enough to proclaim support for negative rights without providing social rights to guarantee them. On some readings, even higher aspirations were ascribed to the republican tradition. Canadian philosopher Douglas Moggach obverses that German idealists like Kant rejected eudaimonist modes of argumentation, but nonetheless ascribed enormous perfectionist expectations onto republican political forms. Free individuals governed by laws they gave themselves would respect each other’s dignity and raise society to a higher rational level than has been seen before. While often criticised, thinkers from Hegel to Marx remained receptive to aspects of this perfectionist vision.[6]

Leipold notes how Marx was receptive to many of these republican arguments, but radically innovative in extending them to the economy and workplace. Leipold reminds us that Marx began his career as a democratic critic of Prussian absolutism, fiercely defending rights to freedom of expression and democratic participation while offering subtle critiques of regime apologists like the late Hegel. Marx and his long-suffering family paid a heavy price for this activism; denied an academic career, his newspapers shut down one after another, exiled from country to country and monitored by secret police. In his mature phase, Marx became increasingly interested in how various forms of economic power aligned with political domination to maintain subordinating social structures. This included the state, but also the workplace. As Marx noted in Chapter 15 of Capital, Volume I, liberal thinkers admirably insisted on the importance of individual rights, the division of powers, and representative participation at the state level.[7] But all this fell away the minute one entered the factory floor, when capitalists exercised autocratic power over their workers resembling the worst features of the feudal system liberals prided themselves on opposing. As Leipold notes:

These descriptions of the relationship between workers and their capitalist employers in terms of despotism were entirely commonplace in Marx’s writings. The power enjoyed by individual capitalists mirrored, Marx argued, the arbitrary power enjoyed by absolute rulers over their subjects. Just as workers could have a ‘public despot’ in the political sphere, they were also confronted by ‘private despots’ in their workplace. … Using the ‘extraordinary wealth of statistics, official reports, and pieces of press reportage’ he had gathered, Marx documented how the workers’ meager pay and long hours, their unsafe and unhealthy workplaces, their monotonous and intellectual unstimulating tasks, were compounded by the fact that the capitalist or ‘factory autocrat’ subjects him [the worker] during the labor process to the pettiest, most spiteful despotism. (p. 306.)

Leipold’s reading of Marx brings him into dialogue with contemporary left-liberal thinkers like Elizabeth Anderson, who have also condemned the forms of domination characteristic of “private government”. Anderson notes how, if Americans were told that the government was now going to tell them when to wake up and go to bed, what they can wear, when they can go to the bathroom, when they are allowed to eat, what to post on social media etc, they would instantly rebel.[8] But, in fact, this is all commonly accepted as simply a natural state of affairs when workers go to their job and are subjected to the rule of capital and capitalists. Unfortunately, we are not nearly so far from the world Marx described as we may think.

Is there an alternative to these forms of domination? Leipold refreshingly offers a partial reconstruction of Marx’s vision of a radically democratic “social republic”. These are mainly sketched out in short, mainly responsive works like The Civil War in France and the “Critique of the Gotha Programme”. Leipold highlights how Marx “condemned the state as a professionalized, hierarchical, and centralized body that has escaped the control of its citizens” by being largely accountable to plutocrats and elites. Changing things would mean “fundamentally transforming” the existing state’s “five main organs: the bureaucracy or civil service, the standing army, the established church, the police, and the judiciary” (p. 376). On Marx’s vision, standing armies would be turned into a militias, the police, judiciary, and bureaucracy would be radially democratised and accountable through direct recall, and the state would be decentralised with more self-governing powers being granted to local assemblies. Aligned with this, workers would, of course, gain far more control over their workplace through an extension of principles of non-domination into the economic sphere to challenge the power of capitalist autocracy.

Leipold’s book is largely a reconstruction rather than a defence of the republican strains of Marx’s thought, meaning we get a good sense of what his “social republic” would look like but not much evaluation of its merits or demerits. I think that the kind of hyper-democratic society envisioned by Marx has a lot of good qualities to it – if nothing else, Citizen Marx should be the final nail in “Marx was a proto-authoritarian” coffin. But we would need a lot of clarity on issues like what basic rights would be guaranteed in such a state and how would they be upheld? Leipold makes clear that Marx thought liberal rights were important historical achievements, even if inadequate for full freedom since they only protected against certain kinds of abuses and were not extended to spheres like the workplace where they were clearly needed. But a lot more could be said on such points to make a case for social republic. Nevertheless Leipold deserves great credit for his exhilarating and learned exegesis on this central topic.

Marx the ethicist

Vanessa Wills’ Marx’s Ethical Vision is a much more philosophical and dense book than Leipold’s. Citizen Marx, as the title suggests, leans heavily on the Marx who kept a close eye on the streets. Marx’s Ethical Vision focuses on the Marx who wrote book-length critiques of idealism and whose work was in constant dialogue with Aristotle, Hegel, Kant, Mill, Bentham and other great thinkers of the Western canon. Discussions of Marx’s epistemology and theory of history, debates over whether Marx was a determinist or a believer in free will, and whether he is best labelled a virtue ethicist, consequentialist, deontologist or something else entirely abound. Wills’ goal is to show that Marx’s thought was “at once ethical and scientific. It is simultaneously a view of the world from the interested perspective of the oppressed and exploited laboring masses and an objective and universally valid account of human existence” (p. 9).

Wills notes that, for many Marxists, ethical arguments have been treated as mere expressions of “ideology”. That is, that the prevailing ethical outlook at any given time portends to a kind of universality while, in fact, being very much a historically relative expression of that society’s structure – in particular, its economic arrangements. Even the most noble and reflective ethicists can be vulnerable to this objection. When Aristotle defended the existence of “natural slaves”, he was simply expressing the common view of a Greek citizen who took for granted that slaves were supposed to do most of the hard work in a civilized polis. When J.S. Mill defended British imperialism for allegedly elevating underdeveloped and immature societies, he was expressing the myopic and chauvinistic Victorian attitudes of his time.

Wills acknowledges the importance of this ideological critique, while pointing out how it has led many to ignore the throughline of positive ethics that persists beneath Marx’s historical analyses of ideology. As she puts it, the

flourishing, development, and well-being of human individuals guides Marx at every stage of his philosophical work and is the basis of his outlook on morality. He argues both that it is the highest goal for human beings, and that it provides the standard by which moral theories should be judged. When Marx criticizes specific moralities, it is not because he has abandoned any moral conception whatsoever. Rather, what rival theories represent abstractly as a desirable state of affairs is, for Marx, a goal to be aimed at through practical revolutionary activity, not merely wished for in systems of moral injunctions. (pp. 44-45.)

Put another way, when Plato insisted that the good could only be obtained when we shed our commitment to doxa and apprehended the true forms of justice, he aimed for the right goal. But Plato overestimated how simple philosophical speculation by the few would be sufficient to break through the doxatic illusions generated by social practices. Overcoming them would require not just philosophical contemplation or even utopian theorising about the ideal republic. It would require practical action and a keen understanding of material reality to erode the social sources of ideological illusion – most notably, sites of domination and power which were stubbornly fetishised and taken for granted as natural by those who profited from them.

Of what, then, might the positive content of Marx’s ethical vision consist? Wills argues it is very much in the tradition of Aristotelean critiques of liberal individualism. A “Marxist approach to ethics can be understood as an attempt in part to recoup the loss, described for example in Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue, inflicted by liberalism’s repudiation of the Aristotelian notion that there is a shared, universal, objective and knowable human nature from which normative claims can be derived about how human social life ought to be arranged.” Wills stresses how Marx’s historicism never entailed a claim that there is no human nature as such. Marx viewed the “essential” characteristic of human nature to be “human’s own power to intervene into natural and social processes, and consequently into their own development” which “allows us to make judgements about what is conducive or injurious to the flourishing of this essential nature while also acknowledging that specific human traits vary over time, and that this variation in appearance has consequences for morality” (p. 49).

Marx followed Aristotle and Hegel in thinking that human nature consisted in the expressive exercise of our human powers over nature and indeed our own self-hood. A good society was one which enabled the development of many of our different and germinal powers; especially higher kinds of powers like socialising and cooperating with others, creative fulfilment through work, philosophising and scientific analysis etc. Being able to exercise our human powers was not largely a matter of innate ability according to Marx; although he of course acknowledged variations in natural talents in the “Critique of the Gotha Programme” and elsewhere. It was a matter of material conditions, since even the most average of persons flourished more fully when they were enabled to develop their powers. As did the society around them.

One of Marx’s dialectical observations about capitalism was that it had clearly succeeded in providing a higher material basis for human flourishing than any previous mode of production. From The Communist Manifesto onward Marx and Engels rhapsodised about how the technological and social changes wrought by capitalism had produced wonders the world have never yet seen. But they were also sharply critical of how capitalism still failed to truly provide comprehensive opportunities for development and flourishing to the vast majority, and had little incentivise to do so. The capitalists running Adam Smith’s pin factory had every incentive to ensure that their workers became very good at making pin heads, because that was conducive to economic efficiency. But they had little incentive to develop any of their workers’ powers beyond that, since there was no profit to be made in doing so. This is why Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations worried that the division of labour would make workers one sided and ignorant unless government stepped in to offset these tendencies. Which it often to be compelled to do, and almost certainly in the face of capitalist resistance to wealth redistribution through social programs and regulation of the workplace.

Marx on the good life

Wills’ book is a remarkably good discussion of these dimensions of Marx’s thought. But it goes further still. One longstanding criticism of Marx’s ethics has been its lack of teleological orientation; an account of “ends” if you will. Even those sympathetic to elements of Marx’s arguments criticise him for a kind of Promethean yearning to develop human powers, without ever specifying what it is good for us to deploy our powers to do. In modern parlance, Marx seems to have too little to say about the “good life.” Indeed, as Wills stresses, he even seems to suggest that, under communism, there will be an “abolition of morality” – sometimes taken to be an argument for an utterly libertine society. But what Marx actually means is that ideological and historically contingent forms of morality which uphold relations of exploitation will be transcended.

What kind of ethical relations and behaviours Marx thinks should govern a socialist society is in unclear. Wills gives three different possible readings. The first and most radical holds that a fully developed socialist society would be so pro-social that there would be no need to make moral requirements explicit anymore. A sense of ethical reciprocity would arise “immanently from human conditions and forms of being”. The second possibility is that moral requirements would persist but be rendered uncontroversial. Individuals would “discharge their obligations because it is already embedded in their forms of life that they would do so”. Finally, a third possibility is that Marx followed Hegel in thinking that a good society would be one where individuals would adopt ethical roles willingly without the need for abstract and formal moral commands. They would see their private will as in line with the “good of society as a universal and collective whole”.

Wills thinks that the first approach is the most plausible and most attractive. If that is the case, then I cannot but disagree emphatically with Marx. As Patrick Deneen notes in Democratic Faith, one of the better arguments for a more egalitarian and democratic society is, ironically, not rooted in these kinds of perfectionist aspirations.[9] Instead, it flows from the Augustinean recognition that human beings have always been, and will always be, imperfect and torn between doing the good and giving into the libido dominandi. When we take this seriously, it actually becomes a pretty good argument for socialism. If you think that power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely, one should be very concerned about how mass concentrations of wealth enable concentrations of plutocratic political power. Not to mention how they enable capitalists to domineer over their workers. Given this, I think something like liberal socialism is a more realistic endpoint for a lot of these Marxist inclinations, grounding a developmental ethic in a society that requires respect for liberal rights and freedoms. Nonetheless, Wills has made a major contribution to not only Marxist scholarship, but moral philosophy, through her brave reconstruction of his ethical vision. She makes clear how seriously Marx took moral and ethical philosophy, and presents a view that competes proudly next to more rival positions.

Conclusion

Marx remains an essential thinker for our era. Ironically, he will continue to be so as long as opponents of Marxism get their way and capitalism persists. This will mean that anyone who finds it discontenting will inexorably turn to capitalism’s greatest critic for insight. In The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon the main character Oedipa Mass comes across a group of conservative anti-capitalists, who explain that they cannot support capitalism because of its bad habit of producing so many Marxists.

It is important to learn more about what Marx had to say in order to offer cogent defences and criticisms of his positions. Citizen Marx and Marx’s Ethical Vision are both essential guides to these issues, showing us sides to the surly Prussian that have been underexplored and underappreciated. I do not think anyone will come away from them thinking Marx was right about everything, or even that he did not make serious errors. But they will come to a better appreciation of Marx as multifaceted thinker committee to human freedom and the full development of the personality in a society free of domination. Marx thought that the free development of each could be a precondition for the free development of all. That remains a noble, if flawed, vision worth learning from.

References

Althusser, Louis 2005, For Marx, Verso

Anderson, Elizabeth 2017, Private Government, Princeton University Press

Cohen, G.A. 1995, Self-Ownership, Freedom and Equality, Cambridge University Press

Deneen, Patrick 2005, Democratic Faith, Princeton University Press

Leipold, Bruno 2024, Citizen Marx: Republicanism and the Formation of Karl Marx’s Social and Political Thought, Princeton University Press

Marx, Karl 1990, Capital: Volume One, Penguin

Marx, Karl 1991, Capital: Volume Three, Penguin

Moggach, Douglas 2022 “Post Kantian Perfectionism”, Academicus International Scientific Journal

Roberts, William Clare 2017, Marx’s Inferno: The Political Theory of Capital, Princeton University Press

Wills, Vanessa 2024, Marx’s Ethical Vision, Oxford University Press

[1] Marx,1991, pp.959.

[2] Althusser, 2005

[3] Cohen, 1995, pp.5

[4] Cohen,1995

[5] Roberts,2017

[6] Moggach, 2022.

[7] Karl Marx,1990

[8] Anderson,2017.

[9] Deneen, 2005.