Text in English, Russian and Portuguese

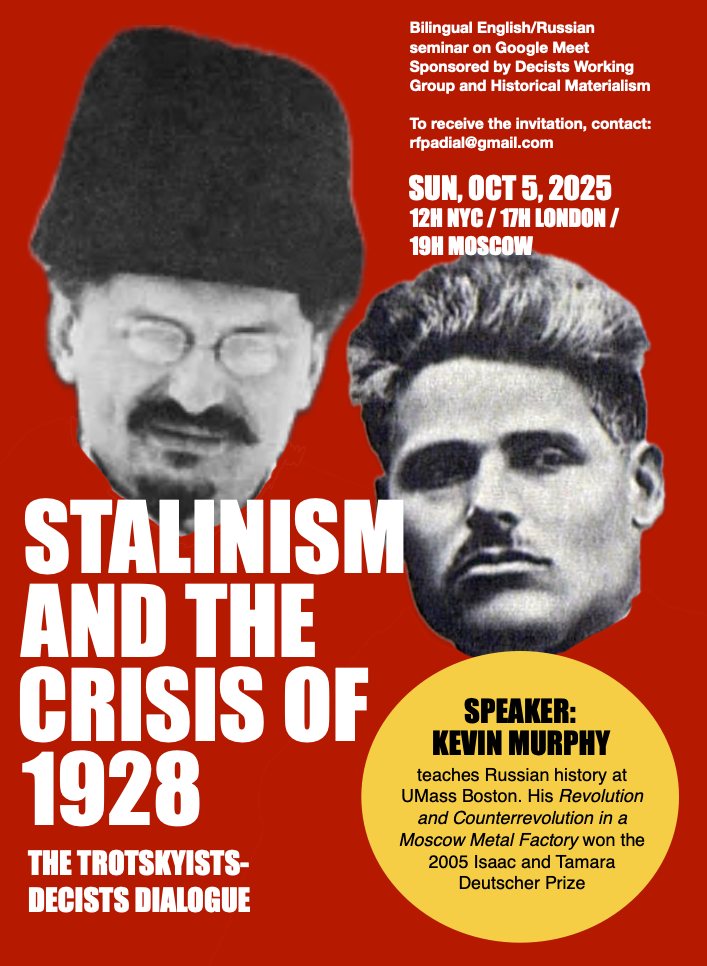

Stalinism and the Crisis of 1928: The Trotskyist-Decist Dialogue

Kevin Murphy

1928 was the pivotal year in the development of the Stalinist system. In a period of just fourteen months, Stalin and his lieutenants defeated two major oppositions—the United Opposition in late 1927, and then, a year later, his former allies, Nikolai Bukharin and his supporters, staunch advocates for continuing the New Economic Policy (NEP). By eliminating both opposition currents and promoting his loyalists, Stalin became the unchallenged ruler of the Soviet Union. Throughout 1928, he had implemented violent “extraordinary measures” against the peasants in the countryside, signalling the start of his six-year ‘war’ against Soviet peasants, who, in turn, organised hundreds of mass rebellions. He escalated attacks on workers’ living standards, largely silenced public dissent and exiled several thousands of oppositionists (including Trotsky). For more than a half century afterwards, very few dissenting voices in the Bolshevik Party would have their views heard at any level of the Communist Party, either at party congresses, at the local level, or in the public press. By the end of 1928, Stalin and his supporters were putting the finishing touches on draconian plans for the First Five-Year Plan that would compel both peasants and workers to pay for rapid industrialisation.

The plan called for fantastic but unrealistic accelerated industrialisation and marked the end of the more lenient NEP, which had allowed limited private enterprise, particularly in agriculture and small-scale trade, in order to revive the war-ravaged economy after the Civil War. The new plan aimed to increase Soviet production from near pre-war levels to two-and-a-half times that in just over four years. In the absence of foreign investment or internal funding, such a plan could only be carried out, as the former Czech historian Michal Reiman argued, by a “very brutal attack on the living and working conditions of industrial workers and the rural population”. Reiman suggests that, rather than a well-planned strategy, Stalin’s 1928 policies are better understood as ad hoc responses to the very deep social and economic crisis of late NEP. For Reiman, the origins of the Stalinist social system of “inequality and privilege” and the regime’s elimination of opposition forces were intertwined. Realisation of the plan required “the existence of a ruling social stratum, separated from the people and hostilely disposed toward it”.

The state’s protracted offensive against Soviet peasants and workers did not go unchallenged and met with fierce resistance. Here, we examine the social crisis of 1928 from the perspective of the two opposition Bolshevik groups, the recently expelled (December 1927) United Opposition and the even more radical current of the Democratic Centralists. We now have a wide range of documents not just from these two groups but between them, illustrating frequent solidarity and criticisms of each other at both leadership and rank-and-file levels. Significantly, the gap between the leaders of the two groups continued to widen over 1928, while, at the grassroots, members showed mutual admiration and even practical cooperation. Statements, correspondence and leaflets offer a fascinating window for understanding how socialists at the time viewed events and hoped to influence the course of the tumultuous year. Here, we explore how both opposition groups analysed the crisis, their respective analyses of the regime and their response to rising workers’ militancy, which, by the late autumn of 1928, generated growing calls for unity between the two groups among rank-and-file members.

As Alexei Gusev indicated at our last seminar, the Decists played a crucial role in both the 1923 Opposition and in the formation of the United Opposition in 1926—particularly Timofei Sapronov, who acted as interlocutor between the Zinoviev oppositionists and the Trotskyists in early 1926. Later that year, the Decists argued against the retreat of the Opposition in the face of threats of expulsion: in October, they criticised Zinoviev and Trotsky for repenting against accusations of “factionalism” and “violation of party discipline”, and broke with the United Opposition. Even Trotsky’s sympathetic biographer, Isaac Deutscher, conceded that the Opposition’s tactical retreats benefited the party leadership. “The Opposition … yielded so much ground and gained nothing. It had renounced co-thinkers and allies, admitted itself guilty of offending against the 1921 ban, called its organization to disband…” In his judgment, the Opposition “had tied its own hands” only “to bring upon itself fresh blows”. As we shall see, even after this break, the Decists’ radical positions continued to receive a considerable hearing among Oppositionists.

Throughout 1927 and again in 1928, the Decists repeatedly aimed their criticisms primarily at Stalin, rather than the Bukharinists–the focus of Trotsky and the United Opposition criticisms. The Decists maintained in their publication Under the Banner of Lenin that, for years, real political power was in the hands of the Secretariat and Stalin. Party committees controlled the “party masses” who, were, in turn, in the hands of secretaries actually appointed from above. Similarly, this process also happened at the “highest party executive body, the Central Committee. Beginning in 1923, the actual leadership of the party gradually passed from the hands of the Politburo to the Secretariat headed by General Secretary Stalin”.

Stalin, in March 1927, made a very rare open declaration for his increasingly strident attacks on Soviet workers (his similar declaration at the July Central Committee 1928 plenum would not be published for another twenty years). At the 5th Conference of the Komsomol in a speech on “rationalisation”, Stalin argued that “not a single major step in our country has been without some sacrifices on the part of certain groups of the working class in the interests of the entire class of workers in our country”. He, therefore, argued that “we should not stop before some minor sacrifices in the interests of the working class”. The Decists, unlike Trotsky and the United Opposition, openly challenged this call for workers’ sacrifice. “Only a man dazed by power, who has already lost the ability to understand the workers, can speak like this”, they declared in their Under the Banner of Lenin programme. It was “under the guise of fighting against ‘certain groups of the working class’”, argued the Decists, that Stalin was waging “a struggle against the entire working class, relying on the non-proletarian classes”.

In 1927, the Decists had continued to argue that there were no significant differences between Stalin and Bukharin on agrarian policies. Although they cited Bukharin’s famous 1925 declaration that “we need to say to the entire peasantry, to all its different strata: enrich yourselves, accumulate, develop your farms”, the Decists insisted “it would be quite wrong to consider that the Stalinist group on questions of village policy takes some fundamentally different, ‘left-wing’ position, as opposed to the openly right-wing position of Smirnov, Kalinin and Kaminski”. For the Decists, the power of the “dominant Stalinist group” and its resort to repression was paramount. They claimed that Stalin had “resorted to obviously fascist methods of struggle, to the formal prohibition of discussion, expulsions from the party, threats of dismissal from work and the use of direct obstruction”. Here, they disagreed sharply with the United Opposition. In Under the Banner of Lenin, they argued that “instead of showing the Party that the main stronghold of the right-wing danger is the Stalin group and the party apparatus subordinate to it” (which had been the position of the entire opposition before the 1926 discussion), the Zinoviev-Trotsky opposition had “repeatedly oriented the Party toward the idea that the Stalin group could itself begin to fight the right-wing danger”.

Almost immediately after the 15th Party Congress in December 1927, several thousand Oppositionists were banished to far corners of the Soviet Union. Trotsky was sent 4,000 kilometres away to Alma Ata in Kazakhstan: the GPU reported he had to be “taken by force” and a crowd of 3,000 saw him off in Moscow with shouts of “Down with the gendarmes!”, “Down with the Thermidorians!” and “Down with the Nazis!”. Until October, the state security guarding him at Alma Ata was relatively lenient: Trotsky hunted, rented a dacha with an apple orchard, received sacks of mail daily and even managed to set up his own mail system from Moscow. Trotskyists and Decists were scattered around the Soviet Union: Christian Rakovsky in Barnaul; Yevgeny Prebrazhensky in Siberia; Karl Radek in the Verkhneuralsk Political Isolator, Decist leader Timofei Sapronov to the far north in Shenkursk. For Trotsky, the necessity of reform within the regime would be paramount throughout 1928, and he counterposed this directly against what he considered ultra-leftist calls from the Decists for revolution. The Trotskyists’ Appeal of the Deportees in January flatly denied that they aimed to “create a second party”, an accusation that party leaders repeatedly levelled against them, although OGPU reports to Stalin show that they understood this was untrue. Notwithstanding his political differences with Trotsky, Sapronov attempted to stay on decent terms with Trotsky, sending him a May Day greeting from Shenkursk.

To understand the enormous changes during 1928, we need to briefly examine the roots of the crisis. The economic calamity of late 1927 shook Soviet society and was central to discussions on all sides—though most Soviet leadership exchanges were inaccessible to party members and Soviet citizens. A similar ‘scissor crisis’ in 1923, as described by Trotsky at the time, had seen the rising costs of underproduced industrial goods start to vary indirectly with the much lower costs of agricultural prices. By late 1923, agricultural prices were only 89 percent pre-war levels, whereas the price of manufactured goods was nearly three times their pre-war level. This meant that peasants’ incomes fell, and it became difficult for them to buy manufactured goods: many stopped selling their produce and reverted to subsistence farming. 1927 brought a similar crisis, and, by the late summer, food queues appeared in many cities, as peasants, unable to afford rising costs for products, started to reduce their marketable produce, Soviet leaders claimed popular fears were exaggerated but, in the last two months, the marketable produce was half that of a year earlier—a disaster compounded by the winter wheat failure in Ukraine.

So drastic was the crisis that, in January 1928, Stalin and his entourage took the unprecedented step of personally travelling to the Urals and Siberia for three weeks to bully local leaders and implement ‘emergency measures’ for procurement on the ‘grain’ front. Central Committee members and 30,000 loyal party activists spread out across the Soviet Union, armed with powers to set up grain procurement troikas (three person committees) purge recalcitrant organizations, arrest peasants and confiscate the property of ‘speculators’ for wilfully withholding grain from the market.

Ostensibly aimed at “kulaks” (wealthier peasants), the harsh measures of early 1928 hit the middle peasants the hardest. Better-off peasants mostly had sold their grain at lower prices, absorbing the loss, while the middle peasants held on in hopes of higher prices, as Moshe Lewin has shown. In Siberia, Stalin lambasted local officials as ‘kulak’ agents, but Lewin showed (and virtually all historians of the Soviet Union today agree) this was a policy aimed at the entire peasantry. ‘Kulaks’ were not a class in the Marxist sense, nor significantly distinct from other villagers. Only one per cent of peasants hired more than one worker, while wealthier peasants earned only five times as much as the poorest peasants. Rather than expressing hostility towards marginally more affluent peasants, other villagers were content that they were willing to hire them or loan them money at a time when the Soviet state failed to do so. V.P. Danilov noted, from the 1927 Soviet census, that the average size of ‘kulak’ land, discounting rented land, was only four times that of a poor peasant. The scale of peasant-wide resistance to Stalin’s offensive was enormous, including over 700 mass rebellions in 1928. Later, during collectivisation and dekulakisation, peasant women repeatedly helped organise collective resistance of millions, including thousands of entire villages. As E.H. Carr first suggested, “It was no longer true that class analysis determined policy”: rather, policy determined “what form of class analysis was appropriate to the given situation”.

The absurdity of the regime’s anti-kulak policies would only worsen over the next two years. Lynne Viola’s archival research has proved that entire villages repeatedly showed solidarity in the face of the state offensive: “we have no Kulaks here” became a “virtual refrain of the late 1920s, an implicit defense of the whole village”. Wealthier peasants understood the implications of the regime’s “anti-kulak” actions and rhetoric, often fleeing to the cities or deliberately lowering their financial status to avoid state repression, including a million in the Russian federation alone. A Politburo decree of January 1930 set regional dekulakisation quotas in the thousands for the highest category–those to be sent to concentration camps, including 15,000 for Ukraine. On the eve of the brutal dekulakisation campaign of 1930, the head of the Russian Federation, Sergei Syrtsov, acknowledged that some local officials argued that, if not enough kulaks were found, “we shall acquire some by nomination”. Sometimes, the peasants did the nominations themselves, drawing lots in order to meet the regime’s kulak quota. A March 1930 OGPU report acknowledged that middle peasants, poor peasants, landless labourers, Red partisans and Red Army soldiers’ families had been exiled and that such cases were “occurring almost everywhere…”.

The “extraordinary measures” of early 1928 met with very different responses from Trotsky and Decist leader Sapronov. In a circular letter to his supporters on 9 May 1928, Trotsky addressed the issue of support for Stalin’s official turn and whether the opposition was ready to support it. “We are, unconditionally, and with all our forces and resources”. He argued that, while they would keep their independence, the shift would increase the possibility of reforming the Party “without great upheavals” and that they would assist in the process, “completely and to the utmost of our ability”. From Shenkursk, Sapronov wrote to the Trotskyist supporter Nechaev that from letters he had received that “we are unanimously opposed to the ‘leftist shift’.

In the Results of the July Plenum, N. Baskakov argued that the Trotskyists were incorrect to characterise Stalin’s shift as ‘leftist’. It was only a “pseudo-leftist” manoeuvre that gave the “proletarian section of the party no reason whatsoever to reevaluate anything”. After three months, it had become clear that “the worker-peasant alliance had broken down and anti-Soviet sentiments had grown among the worker-peasant masses, threatening to erupt in rebellion in some places”. For Baskakov, “top-down manoeuvres” and “reformist compromises” were inadequate for stopping or even slowing down the further slide: the only solution was “a powerful wave of mass protest by the working class”. He insisted that the July plenum marked “a new stage of capitulation by the Central Committee to the kulaks, one that is more decisive and opportunistic than in the four-year period before the 15th Party Congress”. The struggle for grain “revealed an unprecedented decay and class degeneration of the party and Soviet apparatus”. While his arguments were not as extreme as Trotsky’s views on ‘kulaks’, he did assert that kulaks would be “even more brazen in resisting the party’s attempts to implement class policy in the countryside on land reform and taxes”.

A Proletarian Opposition (Decist) statement Facing the Kulaks, with their Backs to the Workers similarly focused on the Stalinist leaders. It noted that kulaks had their grain procurement prices raised, while “decrees concerning the poor are not being carried out”. It cited a Rabkrin report in Pravda that showed that, instead of the mandated 38% of poor peasants exempted from tax in Moscow province, only 23% were—with some villages as low as 15%. The Stalinist leadership were “political intriguers” because they “beat the rightists” while “carrying out their line” themselves. Calling on other workers to “join this resistance”, they declared that “only the organisation and unity of the working class can repel the ever-increasing pressure”.

The April Central Committee plenum reaffirmed the “extraordinary measures” and escalated procurement measures and attacks on peasants. By the summer, a confrontation loomed between the two party leadership groups. Despite the public face of unity at the July Central Committee plenum, the rift between Stalin and his lieutenants against the Bukharinists had reached a breaking point—and the details eventually reached Trotsky. On 11 July, Bukharin met secretly with Trotsky’s former ally Kamenev: later he met with Moscow Trotskyists who relayed Kamanev’s account to Trotsky in Alma Ata.

Even with an abbreviated oral report of the plenum (none of the speeches were published at the time), Bukharin clearly understood–much better than Trotsky–the direction Stalin was moving, toward an increasingly fierce and violent prolonged battle not against kulaks, but the entire Soviet peasantry. Stalin had argued at the plenum that, in order to develop industry, a ‘tribute’ by the peasantry was necessary. Bukharin told Kamenev that his policies would bring ‘disaster’ and a civil war with the peasants, that Stalin would have to “drown the revolts in blood”. Although the Stalin group baited the Bukharinists for “defending the kulaks and NEPmen” (as did the Trotskyists), behind closed doors, they conceded even larger problems. Mikoyan admitted that the scissor crisis would last a long time, that the “scissors cannot be closed”. Molotov claimed that “the middle peasants have become strong”, while Stalin taunted Tomsky for suggesting concessions to the middle peasants. “What if the middle peasants demand concession to the monopoly of foreign trade or a peasant union. Concessions there too?”

Through 1928 and for years afterwards, Trotsky regarded the Bukharinists (allegedly advocates of the ‘kulaks’) as the main danger in the Party. While criticising a 15 February Pravda editorial, he applauded them on several key issues. The editorial had acknowledged “the lagging of industry” and the “extreme kulak danger”, though Trotsky’s solution was to divert industry “what had gone to the kulak” to accelerate “both light and heavy industry”. Despite their differences with the ‘centrist’ Stalinists, who “still have the apparatus”, it remained the task of the opposition to “support every step to the left, even a half-hearted one”. During the July Central Committee Plenum, Rykov, Bukharin and other leaders of the so-called “Right” advocated for a continuation of the New Economic Policy and a less confrontational approach toward the peasantry. Stalin tactfully made concessions to give the appearance of party unity and to solidify his loyalist forces for later attacks on the Bukharin supporters. Bukharin, as described by Kamenev’s report on his brief meeting with him, understood the implications of Stalin’s behind the scenes manoeuvres to pressure the Leningrad organisation to side with him and to flip Politburo leaders Bukharin had counted on. According to Kamenev, Bukharin looked like a man “who knows he is doomed” and warned Kamenev that Stalin would turn the Soviet Union into a “police state”. During the plenum, Stalin disavowed the use of ‘emergency measures’ as a permanent policy, suspended forced requisitions and agreed to raise grain prices for the peasants’ produce. Trotsky misread Stalin’s machinations, claiming that the so-called ‘Right’ had emerged “entirely victorious from its first skirmish with the centre, after four or five months of ‘left’ politics”.

For Trotsky, the Bukharinists represented a ‘Right danger’ towards Thermidor and possibly counterrevolution, even if they were not conscious of it. Perhaps this explains why Trotsky found so few of their words to quote to prove this accusation. “We do not mean by this that everyone who promotes this policy wants consciously to go all the way to Thermidor. No, the Thermidorians, and even more the semi-Thermidorians, have never been distinguished by a broad historical awareness”. For Trotsky, the ‘Right danger’ was “less the danger of an open, full-fledged bourgeois counterrevolution than that of a Thermidor, that is, a partial counterrevolutionary shift or upheaval” which could last for a prolonged period. While Stalinists controlled the party apparatus (as Trotsky acknowledged), he argued that reform of this apparatus could be achieved, though he failed throughout 1928 to offer much in terms of specifics on how the opposition’s proposed reforms could be achieved. In an exchange with Borodai that we will examine later, it was this possibility of reform that underpinned his conclusion that Soviet power remained intact. But, for Trotsky, the implications were enormous: a victory for the ‘Right” would be “a partial counterrevolutionary shift”, such that a return “from Thermidor to the dictatorship of the proletariat could only be effected through a new revolution”. Trotsky thus based his entire analysis of whether reform was possible on who would win the leadership battle, and a victory for Stalin would be the much better outcome, keeping hopes for reform alive.

The late 1928 rise in workers’ militancy helps us understand calls for cooperation and even unity among rank-and-file Trotskyists and Decists. Top secret reports to Stalin include hundreds of pages documenting protests across the Soviet Union. By the fall of 1928, as Vladimir Brovkin concludes, the “temperature of frustration at the factories and plants rose, ready to boil over”. This renewed worker radicalisation ranged from simmering anger amongst relatively privileged metal workers in the Soviet capital to better organised and ultimately open rebellion by Ivanovo textile workers.

Discontent among Moscow’s Hammer and Sickle workers was widespread. At a shop recruitment meeting in September, one worker declared, “I will not enter the Party because communists are embezzlers and thieves”. At another meeting, a woman worker asked, “Is the Party running a correctional institution? Why do you accept all kinds of garbage and keep those who do nasty things?” The reputation of the Party at the massive Hammer and Sickle factory was so bad that even the factory newspaper acknowledged that “there is distrust of the self-criticism campaign” and a “clear anti-party mood as a result of the intensification of the working day and the regime’s ‘rural policies’”. In Why We Are Non-party, Hammer and Sickle workers complained that “we do not want to vote for what has been predetermined”; one complained that “instead of explaining things, party members would rather curse you out”, and another protested that a cell secretary smeared his opponents for having “white guardist views”. Three women explained that they refused to join the party “because our tongues are whole” and “only those who swallow half their tongues beforehand are met with open arms”. Other women workers in the factory complained of party members’ sexual assaults and even reported the murder of a woman. The reputation of the Party was so damaged that, on International Women’s Day 1928, women disrupted the male speaker’s report and were forcibly removed.

Stalin’s 1928 self-criticism (samokritika) campaign was one of many regime gimmicks initiated to deflect attention from its increased exploitation of Soviet workers. The head of the party’s Central Control Commission admitted the manipulative nature of the 1928 campaign, saying that it was better to “release the reins” by allowing “workers to criticise us” than to have workers take action on their own. As OGPU reports from around the Soviet Union illustrate, Hammer and Sickle workers also sympathised with the plight of the peasantry. An anonymous note to a speaker at a general meeting “all we hear from you is that the village has kulaks … if you examine the villages and then estimate your possessions, the figures will show who is the kulak.” Other notes asked why grain was still being exported by the government during the grain crisis and one asked if “grain will again be taken forcibly from the peasants?”

Intimidation by hardened party loyalists had marked the 1927 political discussions with Oppositionists who were routinely whistled at and shouted down. Such tactics continued into 1928 as effective weapons of regime loyalists. Occasionally, workers were so angered by the Party’s heavy-handed policies that they voiced their grievances openly. In February 1928, bolt shop workers struck over a 20 percent wage reduction. At an extraordinary meeting after the strike, the party factory secretary wrote a resolution condemning the strike action, but his proposal did not “receive a single vote” while “workers who spoke up blamed the stoppage on the factory committee and administration” and argued their strike was justified.

The factory newspaper acknowledged that fear of reprisals had intimidated many workers from openly speaking out at meetings. Yet, in the collective agreement meeting in December, many did: several workers argued that production savings were “being taken out of workers’ pockets”, while a party member was reprimanded for complaining that “They squeeze and oppress us and suck our blood dry”. At a factory-wide delegates’ meeting in December, a party loyalist attempted to shut down discussion over wage increases, arguing it was “incorrect” to “raise the question of raising pay… We should raise productivity and thus we will lower the costs of production”. His claim that wage discussions were being raised by oppositionists “to disrupt our collective agreement” was immediately challenged by the next speaker: it was raised because of the “discrepancies” between shops on wage and skill grades.

We must keep in mind that this discontent in the Soviet capital, where metal workers were privileged economically and politically, was the lower parameter of workers’ anger. At the other extreme, the epicentre of workers’ resistance to Stalinism was among textile workers generally, and in Ivanovo specifically. Better organised but with lower wages and intensifying productivity, more than 15,000 textile workers struck in 1928, by far the highest rate of strike action in any Soviet industry. Jefferey Rossman’s book, Worker Resistance Under Stalin, focuses on Ivanovo textile workers and shows that intensification of labour with near starvation wages led to a series of mass worker rebellions in Ivanovo. We can also see some rank-and-file Trotskyists either never received Rakovsky’s no-strike pledge (which we will cite momentarily) or chose to ignore it, siding repeatedly with their workmates against the state offensive.

Trotskyists were part of a wider milieu who helped build the resistance among textile workers and were part of the later rebellion that rocked the regime in 1932. Textile workers had been at the centre of the 1925 strike movement and again in 1928 when 15,000 struck, the most militant sector of resistance of any industry. The intensification of the work process while offering only semi-starvation rations and lower wages sparked this new militancy; Trotskyists repeatedly appear as part of this resistance. In December 1927—the same month of their expulsion from the Party—delegates at a textile conference praised Trotsky for his foreseeing that the seven-hour working day would allow management to “pile extra work on the worker”. A March 1929 report of the All-Union Trade Union of Textile Workers noted rising dissatisfaction among operatives as the size and intensity of strikes had increased in 1928 and agitation against the regime policies had become common on the shop floor. The report mentioned five workers by name, including a Trotskyist in the Moscow region who enjoyed “great popularity among the workers”. At the luzha Spinning Mill in 1930, Trotskyists distributed leaflets stating that “We cannot remain silent while they exploit us, while they fail to give us a slice of bread, while our earnings fall on a daily basis”. The appeal concluded that “We must not allow this, but must collectively say: Give us bread, free trade, a reduction in prices, and an increase in pay! This is what Trotsky fought for—and for this, he was shamelessly driven out of the party”. The OPGPU noted with alarm that “many workers cited these leaflets” and concluded that “Trotsky was really correct in his battle with the party”. A leaflet distributed in 1931 at a Kineshma mill declared that “Our rulers of the Soviet Union are more feeble than the bourgeoisie… Down with Soviet rulers! Long live Trotskyism! Long live Leninism and the Leninist way!” During the winter of 1931-2, a sharp decline in rations, rising truancy and illness led local officials to request the centre to improve their procurement efforts because “Anti-Soviet and Trotskyite elements” had used the deteriorating situation “against the Party and the state”. A report on the 1932 Teikovo rebellion stated that, as a result of delays in explaining the new rationing system and deficiencies in supply agencies, “unhealthy moods arose among a certain segment of workers”, who were “used by Trotskyites and class–alien elements, who managed to put significant groups of backward workers under their influence and organise a strike movement assault against party and Soviet organisations”.

The renewal in worker radicalisation went unmentioned by Trotsky, even with reports that signalled otherwise. A June letter from Moscow to Trotsky showed that “the mood among the masses, in connection with the collective agreements is obviously one of hostility … toward the official trade union organizations is scornfully hostile… On all questions … workers go directly to the secretary of the party cell, saying they want to deal directly with the boss and not with the frontman”. The report pointed out that workers were “very interested in the Opposition” with only three dozen capitulations. Yet, even as late as October 1928, Trotsky continued to refer to the “present passivity of the masses…”

By the later summer, new calls calling for unity between the Trotskyists and Decists emerged. Sapronov’s August 5th letter to the Trotskyist oppositionist Nechaev attests to significant Trotskyist support for unification. Nacheav stated that it was “possible and necessary to talk about unification” to which Sapronov replied, “Your position, although shared by a large number of comrades in your group, is not yet ideologically dominant”. Sapronov said he often received similar letters from members of the group, with one comrade expressing support for a joint statement to the Comintern Congress (July and August): “We need more organisation and joint action”. Sapronov replied. “A joint statement is the beginning of unity, which your leaders apparently do not want”.

The Decist leader V.M. Smirnov and Trotsky each worked to convince their ranks to not join forces with the other group. Smirnov shared Trotsky’s intransigence against unification: in a 14 August letter to his Decist comrades, he argued that “association with this tendency is useless and harmful”. Like Trotsky, he acknowledged that there were “good guys” among the Trotskyists who were sometimes “caught among them, they must be pulled out of this swamp” not by making any “concessions to the moods and views of this swamp, but by strongly denouncing these views”. For Smirnov, the Trotskyists’ reform strategy undermined a more combative approach. “They are ready to make the mass a weapon for their notorious reform, but afraid to death of the veritable class struggle, rightly fearing that they will step over their equivocating ‘guidelines’”. On 30 August, Trotsky wrote that “Smirnov and others are fiercely criticising our “capitulationism” … a clear attitude towards them must be taken”.

On 12 October, a Voronezh colony of Trotskyist exiles responded to a Sapronov letter and excerpts from a Smirnov letter. What is striking is that, despite harsh words for both Decist leaders, the letter emphasised the possibility of collaboration because of the “great danger” caused by “the cowardly capitulation of the highest organs of the Party and soviet power to the capitalist forces”. This meant that the primary duty of the opposition was to liquidate among themselves the now irrelevant political scores of the past for “the revolutionary cause of the future”. They criticised Sapronov for his accusation that the Opposition ignored the “worker question”, and claimed he resorted to methods of polemics that were “often used by Bukharin’s Garda and the loyal Stalinist apparatus”. Smirnov, in particular, had gone so far that he “is singularly concerned with inciting and aggravating an unnecessary fight”. His usual “demagogy, slander, fraud, gross falsification, empty pompous shouting, and sheer hysteria” provided enough for irrefutable evidence “for maintaining a separate existence”. While mentioning their long-standing advocacy of “deep party reform as a prerequisite for the reform of the Soviet state”, this was not their emphasis. They even “went so far as to assert that party leadership is actually crossing fatal historical limits and the path of intra-party reform is becoming less and less likely” – a remarkable admission, given that this was the main issue that caused the breach between the two groups. They curiously quoted Trotsky’s provocative statement that “the victory of the right wing over the dictatorship of the proletariat would no longer be achieved with the methods of party reform alone”. Although this reform strategy versus the Decists’ revolutionary programme remained the primary issue that separated the two groups, they nevertheless concluded their appeal with a call for unity, stating, “We believe that we have no irreconcilable differences of principle and let us not invent them anymore. Enough squabbling. Time insistently calls for revolutionary unity, for Bolshevik determination”.

The rising tide of workers’ resistance propelled these calls for unity. In an 21 October article on Bonapartism, Trotsky conceded that, amongst his supporters, some considered the Decists to be “pretty good fellows”, but argued their strategic goal should be to “take away the best elements from among them with the help of their own documents” (here, he meant especially the writings of V. Smirnov). The next day, Trotsky again acknowledged that some of supporters “favoured not only joint work with the Democratic Centralists but even total merger”. Isaac Deutscher provides a fascinating glimpse of the generational fault lines that had developed among the Trotsky supporters, which entailed far-reaching political implications. By the spring of 1928, “two distinct currents had formed in the colonies”. The more conservative “conciliators” were not about to surrender to Stalin “but they wished the Opposition to mitigate its hostility towards his faction and to prepare for a dignified reconciliation with it on the basis of the left course”. Although Deutscher concedes that it was “well nigh impossible to disentangle their motives”, these were mostly men of the older generation, for whom “the nostalgic feeling for their old party was extremely strong”. They were also more conservative as “enlightened bureaucrats, economists and administrators, who had been more interested in the Opposition’s program of industrialisation and economic planning than in its demands for inner-party freedom and proletarian democracy”. Wave after wave of these more conservative older men would capitulate to Stalinism.

The “irreconcilable Trotskyists” were mostly younger men, for whom “expulsion from the party had been less of a break in life than it had been to their elders”. Politically, they had been drawn to the Opposition by its call for proletarian democracy. They were hardened enemies of the bureaucracy and determined anti-Stalinists. The more extreme of this grouping, argues Deutscher, “found that they had much in common” with the Decists. Significantly, Deutscher states that after official party policy changed at the July Central Committee Plenum, the more radical Trotskyists had the upper hand in “nearly all opposition centres”.

By October 1928, the GPU treatment of political exiles became notably harsher—presumably under orders from Stalin. This was an ominous sign, as Stalin was no longer apprehensive of any repercussions arising out of harsh treatment of the opposition. The turn illustrated Stalin’s growing confidence in politically annihilating both sections of his opponents. Trotsky ceased to receive letters from friends and followers: according to his son Lev Sedov, they were “under a postal blockade”. The secret mail between Alma Ata and Moscow vanished without a trace. The GPU intensified repression against the more radical Trotskyists and the Decists.

In the Prophet Unarmed, Isaac Deutscher describes how, in the face of increased repression, Oppositionists connected with the discontent in the factories in the last months of 1928. Between 6,000 and 8,000 Left Oppositionists were imprisoned and deported: these tended to be younger activists who willingly chose prison and exile over capitulation. Their boldness was fuelled by growing anger across the Soviet working class. Workers’ discontent was even reported in Pravda: it published a report on the rampant foremen abuse at a Smolensk wood working factory that included bribery and sexual assault. A Decist activist challenged the report’s assertion that such abuse was “unheard of”, insisting that the rise in managerial abuse could be “encountered in one or another form, in one or another degree at any factory, at any plant, at any enterprise”. Workers ridiculed the so-called the regime’s “left course” and the slogan of “self-criticism” that had been “unable to halt the growth of discontent”. Oppositionists in Hammer and Sickle spoke “very energetically” in the collective agreement campaign, with one party loyalist acknowledging that there was “a large group of oppositionists”. Despite increased state repression, party reports in early 1929 noted that “recently the opposition have developed their work up to creating cells” in different shops, and had even organised their own meeting in December 1928. Isabelle Longuet has shown that opposition support was so widespread in Moscow that even non-party workers distributed tens of thousands of their leaflets against the deportation of oppositionists, for wage increases in collective agreements and for supporting other striking workers in Moscow–activity that ran directly counter to the official policy of opposition leaders.

Trotsky and his closest collaborator, Christian Rakovsky, exiled in Astrakhan, largely missed this growing radicalisation, even with reports of workers’ warm reception to Opposition agitation. In October, Trotsky continued to talk about the “passivity of the masses” which he attributed to the “failure of the old ways” which “have disappointed them and new ones have not yet been found”. Rakovsky was even more pessimistic about the fighting capacity of Soviet workers. In an August 1928 letter to Nikolai Valentinov, Rakovsky declared that the opposition had been correct to have “sounded the alarm on the terrible decline of the spirit of activity of the working classes, and on their increasing indifference towards the destiny of the dictatorship of the proletariat and of the Soviet state”. According to Rakovsky, “the flood” of public scandals were a direct result of “his passivity of the masses (a passivity greater even among the communist masses than among the non-party masses) towards the unprecedented manifestations of despotism which have emerged”. By November, apparently enough reports from Oppositionists in the factories had reached Trotsky, so that, despite the mail blockade, he belatedly changed his positions on the worker radicalisation that the Decists, including Borodai, had long noted. “Certain symptoms are at hand”, such as Stalin’s “self-criticism” deflection, which suggested that the “political revival has already begun”.

By late 1928, Trotsky also started paying much more attention to the Decists. Having largely ignored them until now, he mentioned them eight times in his writings of late 1928, devoting more attention to the Decists over several months than he had to the Soviet working class over the entire year. On 22 October, in reply to Teplov, Trotsky conceded that the Democratic Centralists had “come onto the agenda now in all the exile colonies” because unincarcerated Decists were active in Moscow, Kharkov and other cities. “We will win the workers away from them with a courageous and determined policy on the weightiest questions, on the one hand, and with a campaign of clarification, on the other”.

The exchange between a worker Decist, Borodai, and Trotsky has long fascinated socialist critics of Trotsky’s position. Given the context of renewed calls for unity among both groups, Trotsky’s response can now also be read as an attempt to seal off the Trotskyists from the Decists. Borodai’s letter commented on the increased receptivity to Opposition views. “We are observing that in the lower strata of the party, namely, its working-class part, as well as among the broad layers of the non-party working masses, sympathy and support for opposition views are growing. They are real. There is a root in the masses, in the working class”. Borodai’s polite tone (translated into English by our Working Group for the first time) and his “comradely wave of discussions” with Trotsky’s supporters was not reciprocated by Trotsky himself. He accused Borodai of not understanding dialectics, and repeatedly complained that Borodai posed his questions incorrectly, “You put the fifth question just as inexactly as the first four…”

Trotsky was especially annoyed by a Kharkov Decist leaflet claiming that the October Revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat had already been liquidated. This assertion was “patently false” and these Decists had “done much harm to the Opposition”, he responded. He also stated that comments by V. Smirnov “sound as if they were specially calculated to prevent a rapprochement and to maintain a separate chapel at all costs”.

Trotsky also took particular umbrage at Borodai’s fourth question: “Are you thus putting entirely within quotation marks ‘the Left course’ and the ‘shift’ that you once proposed to support with all forces and all means?” Trotsky perfectly well understood the question but chose to rally his supporters with outrage, “This is a downright untruth on your part. Never and nowhere have I spoken of a Left course. I spoke of a ‘shift’ and a ‘Left zig-zag’”. He then answered the substance of Borodai’s letter: “A serious and intelligent Oppositionist will say, in any workers’ cell, in any workers’ meeting: ‘We are summoned to fight against the Right wing—that’s a wonderful thing. We have called on you to do this for a long time.’” Here, Trotsky implies that incarcerated worker Decists like Borodai were not all that serious, nor intelligent, for focusing their fire against Stalin.

Five of Borodai’s questions focused on the same general theme: the nature of the regime, its repression, the party apparatus and whether the dictatorship of the working class still existed. Has the Party degenerated? Do we still have a dictatorship of the working class? Is the degeneration of the Soviet apparatus and Soviet power a fact? Is it still possible to harbour illusions towards the Stalinists as still capable of defending the interests of the revolution and the interests of the working class? Who can guarantee that tomorrow they will not wash their hands of the blood of the Bolsheviks? Borodai ended his letter stating that the questions “I have put before you, I think that if not today, then not tomorrow, the working class will put them before us right up front, and we must be able to answer them”.

Here Trotsky’s method of analysing whether the Soviet Union remained a ‘workers’ state’ was based entirely on whether reforms were possible–is convincing and consistent, though completely at odds from what his later followers would argue. In his long response, Trotsky never mentions nationalised property as a criterion for judging the regime. For Trotsky, the crucial issue, which he states repeatedly, is whether reform within the existing party and state institutions was still possible. “Has power slipped out of the hands of the proletariat? To a certain degree, to a considerable degree, but still far from decisively. As for the proletariat, it can regain full power, renovate the bureaucracy and put it under its control by the road of reform of the party and the Soviets”. And again, “The question thus comes down to the same thing: Is the proletarian kernel of the party, assisted by the working class, capable of triumphing over the autocracy of the party apparatus which is fusing with the state apparatus? Whoever replies in advance that it is incapable, thereby speaks not only of the necessity of a new party on a new foundation, but also of the necessity of a second and new proletarian revolution”. And, yet again, “Are the tens and hundreds of thousands of workers, party members and members of the Communist Youth, who are at present actively, half-actively or passively supporting the, Stalinists, capable of redressing themselves, of reawakening, of welding their ranks together “to defend the interests of the revolution and of the working class”? To this, I answer: Yes”.

From a Marxist perspective it would be hard to disagree that his emphasis on the political control of the state was indeed the central issue. Prior to 1933, Trotsky would repeat this emphasis many times. Thus, in The Third International After Lenin, he argued that “the socialist character of industry is determined and secured in a decisive measure by the role of the party. If we allow that this web is weakening, disintegrating and ripping, then it becomes absolutely self-evident that within a brief period nothing will remain of the socialist character of state industry, transport, etc”. And, in a similar formulation in 1931, Trotsky suggested that “If we proceed from the incontestable fact that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union has ceased to be a party, are we not thereby forced to the conclusion that there is no dictatorship of the proletariat in the USSR, since this is inconceivable without a ruling proletarian party?”

In a February 1935 essay The Workers’ State, Thermidor and Bonapartism, Trotsky belatedly acknowledged that “The Thermidor of the Great Russian Revolution is not before us but already far behind. The Thermidoreans can celebrate, approximately, the tenth anniversary of their victory”. Thermidor had been the main issue that earlier divided the Decists from the Trotskyists, and he had now drawn the same conclusion that the Decists had in 1926, and even a year earlier! Yet, in the same article, he ridiculed the Decists for claiming “Thermidor is an accomplished fact!” Rather than conceding that he had been wrong in provoking this split, he simply invoked his newly revised definition of a workers’ state: “The prognosis of the Bolshevik-Leninists … was confirmed completely. Today there can be no controversy on this point. Development of the productive forces proceeded not by way of restoration of private property but on the basis of socialization, by way of planned management”.

The Decists, on the other hand, had correctly understood Stalin’s ever widening grip on the party and apparatuses but incorrectly tied such control to his changing social policies. While the Decists had correctly argued that Stalin was the leader of Thermidor against party democracy, they also continued to assert that Stalin was the leader of ‘kulak democracy’ at a time when he was, in fact, laying the groundwork for his “destruction of private farming” as Deutscher correctly wrote. Yet there was a fundamental difference between the errors of the Decists and that of Trotsky’s opposition. The Decists would later correct their analysis, moving toward the Marxist theory of state capitalism. Trotsky’s focus on the Bukharin and the so-called ‘Right’ instead of Stalin would continue for years, leading to his initial support for collectivisation. His failure to thoroughly reevaluate his incorrect analysis proved to be a catastrophe for the revolutionary opponents of Stalinism.

After Trotsky’s deportation to Prinkipo, Turkey in January 1929, Rakovsky—as his most trusted collaborator—became the de facto leader of the internally exiled Oppositionists. While communication became much more difficult, Rakovsky, along with M. Okudzhava and Vladislav Kossior issued the following stunning statement, discovered by Alexey Gusev, on the Opposition’s attitude toward strike action in their Statement on the Goals of the Opposition, What should be emphasised is that this article appeared in Trotsky’s Bulletin of the Opposition published in Paris in October 1929 without criticism from Trotsky.

The duty of the opposition is to channel the demands of the working class into the framework of trade union and party legality, rejecting those forms of struggle which, like strikes, for example, harm industry and the state, and thus harm the workers themselves. Strikes are harmful to industry and the state, and thus to the workers themselves. The Leninist opposition must resolutely repel attempts by petty-bourgeois and even openly counter-revolutionary elements to use the discontent of the working masses for their own political ends.

Rakovsky, Okudzhava and Kossior framed their no-strike pledge within the context of their reform strategy: “We are in favour of reform and we are resolutely opposed to any adventurism. Our position does not stem from a foolish theory about the ‘nature of power,’ which provides no basis for reliable reformist tactics”. But it was also formulated in terms of party loyalty: “Since we can influence the non-party working masses, it is our duty to direct their efforts toward combating the rightist and kulak dangers. For industrialisation and collective farm construction!” Therefore, it became “the duty of every conscious Leninist oppositionist to resolutely oppose deviations from our party’s reformist line, regardless of whether they lead to capitulation or decimation”. Neither the authors of this statement nor Trotsky offered a balance sheet of how this reform strategy was working, though the authors conceded their strategy was “complex and responsible … like walking on a knife edge”. Their task was to simultaneously “strengthen the authority of the Soviet state, defend it from all overt and covert enemies, support the centrist leadership in all its measures aimed at ensuring the security of the Union, and at the same time fight against the methods of violence employed by the centrist leadership against the Party and the working class”.

On the issue of organising strikes, the September 1927 Platform of the Left Opposition included only a terse statement on strikes, stating that “in the state industries the decision of the Eleventh Party Congress, proposed by Lenin, remains in force. As regards strikes in the concession industries, the latter shall be regarded as private industries”. On 21 October, in his only statement on strikes in 1928, Trotsky (like the Decists) pointed out that strikes were still legal, referencing the Role of Trade Unions at the Eleventh Party Congress. Though strikes were “an extreme measure”, under certain circumstances it “may be the party duty” of Oppositionists when “all other means for obtaining realizable demands had been exhausted”. Trotsky emphasised going through official union and party channels. The problem, in practice, was that most strikes by late NEP were wildcat strikes that had circumvented official channels—precisely because of the state’s hostility against work stoppages and the capitulation of trade-union organisations. Nowhere does Trotsky openly call for workers to fight the state offensive against the working class by using their primary weapon that defined Russian workers as the most militant in world working-class history–the strike.

The Decists had a very different approach to utilising strike action as the crucial weapon for defending the Soviet Working class. The Decists made this argument in their May 1927 statement, Under the Banner of Lenin. They argued that “previously, the trade union could force the owner to submit to the arbitration court in any conflict, now the owner, regardless of the consent of the trade union, can transfer the case to the arbitration court. As a result of this situation, illegal strike committees are usually elected during strikes, and there are rudiments of illegal trade unions (i.e. mutual aid funds)”. Recounting the strike activity under NEP (particularly the 1925 strike wave) they also complained that workers were “still deprived of the possibility of applying strike action in state enterprises, even though all other means have been exhausted”. Allowing workers to strike in state-owned enterprises would “boost workers’ confidence in unions” but opposition to these proposals “remained a mystery”.

Under the Banner Lenin also criticised the Trotskyists for “unfounded pessimism about the working class, whose ‘shop-floor interests’ are said to prevail over class interests at present”. This hindered their ability “to put forward slogans that could really win the sympathy of the working class for the opposition and active support for it”. They claimed that, since October 1925, wages had ceased to increase, and more recently had declined, while the “output per worker during this period has risen by at least 15%”. While unemployment had increased by 385,000 people over the previous half year, i.e. by 36%. The “classes whose domination had been eliminated or undermined by the October Revolution: the Nepman, the kulak, the bureaucrat are growing and multiplying”. While treating these forces equally, the Decists perceived the origins of a new, hostile ruling class, “The state and economic apparatus is firmly seized by an irremovable caste of officials. These officials are already confronting the working masses as a new ruling class, embodying in their person the unheard-of growth of bureaucratic perversions of the workers’ state”.

Where they had the leverage, the Decists attempted to promote strike actions. A Decist leaflet addressed to “the working men and women of the ‘Red October’ Factory in 1928 indicates they had a cell in the confectionery, and encouraged strike action. It commented that “our bureaucratic revolutionaries are building ‘socialism’ at an unremitting tempo. They are industrialising our country; they are enhancing the productivity of labour; they spout red words and revolutionary slogans next to newly introduced “technology” in our factories and mills. But in “our own factory” productivity was increased by 24% which, they argued, came entirely “on the backs of workers”. They should no longer act “like sheep” to the demands of the “brazen bureaucracy”. The leaflet called for workers to, “Refuse work according to the new norms! Put strike actions to use, all the power is with you! Organize around the true proletarian party of oppositionists. COMRADE WORKERS, WE CALL YOU OUT TO STRIKE”.

Similarly, in September 1929, ‘Trotskyists’ leaflets were found across Moscow districts, although they were signed by “Sokolniki group of Bolsheviks-Leninists Sapronovists”, according to the Moscow Regional Committee. The leaflet was addressed to ‘All Workers’ and they claimed were now subject to “hard labour as they have been exposed to the burden of socialist competition under official-bureaucrat’s whip”. The leaflet noted that the three “traitors”—Radek, Smilga and Preobrazhensky—had capitulated to Stalin. It also mentioned that, two years previously, “there were only a few worker Bolsheviks in prison, and now thousands of them are being imprisoned, but Trotskyists still argue that it is their own platform that is being fulfilled.” It ended with a plea, “Comrades Workers! DEMAND THE RELEASE OF YOUR DEVOTED BOLSHEVIKS-LENINISTS FROM PRISON AND EXILE. LONG LIVE LENINIST OPPOSITION!”

That the Decists used the “Bolshevik-Leninists (i.e. Trotskyists, KM) Sapronovists” designation rather than their normal Proletarian Opposition is highly unusual—the only such occurrence we have yet found. It would appear that rank-and-file oppositionists, in face of increased arrests and with their ranks depleted, had found a working compromise with the Trotskyists in which the Decists would work under the Trotskyists banner while maintaining their independence. Yet it also ridiculed the formal Trotskyist position for claiming that, despite thousands of arrests, their platform was being fulfilled. The call for workers to demand the release of the comrades reads as almost a desperate plea by a shattered revolutionary group that had lost in their desperate battle against the repressive apparatus. Over the next two years, fewer and fewer revolutionaries would remain at liberty, and no evidence from the archives has revealed any organized opposition after 1932.

An honest appraisal of the Decists compared to the Trotskyists shows that, on many issues, their arguments and actions appeared far more convincing. What might appear as a rather obscure discussion on a reformist versus revolutionary approach to the party leadership had profound implications, especially in mobilising workers’ solidarity and organising strikes. Rakovsky’s party loyalty plea, that it was the “duty of the opposition is to channel the demands of the working class into the framework of trade union and party legality” at a time of mass arrests of oppositionists was comparable to Trotsky’s loyalty pledge in May 1924 at the Thirteenth Party Congress: “We can only be right with and by the Party, for history has provided no other way of being in the right”.

Moreover, the admiration and apparent cooperation between ‘irreconcilables’ of both groups was at odds with the actions of their leaders. We can only speculate whether a more radical and united opposition may have had an impact on the trajectory of events, but we do know that Moscow was the stronghold of both the Trotskyists and the Decists, and that they were talking to thousands of workers. We also know that, repeatedly over recent years, key developments had raised the confidence among workers to fight, transforming simmering anger into class-wide militancy and even revolution. This happened on Bloody Sunday 1905, after the Lena massacre in 1912, the proroguing of the Duma in September 1915 and on International Women’s Day 1917, when a handful of Bolshevik women textile workers ignored party leaders and initiated the revolt that would overthrow the Tsar.

In many ways, Trotsky was clearly not the revolutionary defender of the Soviet working class against Stalinism that he has been depicted by his epigones. This mischaracterisation can be partly explained by a similar generational divide between more conservative older Trotsky loyalists and younger, less dogmatic Marxists. Most older Trotskyists today have never read Trotsky systematically nor critically yet spent decades defending the “orthodoxy”. At the key juncture in development of Stalinism, Trotsky and his older comrades viewed the Bukharinists and so-called “Right” as the main danger of capitalist restoration. That perspective, rooted in an inaccurate fear of ‘kulaks’ and Trotsky’s Bonapartist analysis, would remain operative for years despite its increasingly disconnected depiction of Soviet reality. Trotsky’s low point was reached in 1935, when he criticised Stalin’s meagre allowance of kitchen gardens to pauperised collective farmers, those destitute peasants Stalin had viciously brutalised for most the preceding seven years. For Trotsky, this represented a step to the ‘right’ and a concession to potential “kulaks”.

A new generation of socialists, less dogmatic and more open to a critical appraisal of Trotsky’s actual positions, will help us understand the roots of these theoretical and historical divisions that have divided revolutionary socialists for much of the past century. The Decist opposition, the most consistent and radical socialists, will surely help us understand the origins of Stalinist system.

Сталинизм и кризис 1928 года: диалог троцкистов и децистов

Кевин Мерфи

1928 год стал поворотным моментом в развитии сталинской системы. Всего за четырнадцать месяцев Сталин и его соратники разгромили две основные оппозиционные силы — Объединенную оппозицию в конце 1927 года, а год спустя — своих бывших союзников, Николая Бухарина и его сторонников, ярых сторонников продолжения Новой экономической политики (НЭП). Устранив обе оппозиционные силы и выдвинув своих сторонников, Сталин стал безраздельным правителем Советского Союза. На протяжении 1928 года он проводил жестокие «чрезвычайные меры» против крестьян, что ознаменовало начало его шестилетней «войны» против советских крестьян, которые, в свою очередь, организовали сотни массовых восстаний. Он усилил наступление на уровень жизни рабочих, в значительной степени подавил публичное несогласие и сослал несколько тысяч оппозиционеров (включая Троцкого). В течение более полувека после этого лишь единицы в большевистской партии осмеливались высказывать свое несогласие на любом уровне Коммунистической партии, будь то на съездах партии, на местном уровне или в публичной прессе. К концу 1928 года Сталин и его сторонники дорабатывали драконовские планы Первого пятилетнего плана, который должен был заставить как крестьян, так и рабочих платить за быструю индустриализацию.

Проект ускоренной индустриализации, выдвинутый планом, был грандиозным, но нереализумым; он ознаменовал конец более мягкого НЭПа, который допускал ограниченное частное предпринимательство, особенно в сельском хозяйстве и мелкой торговле, с целью возрождения разрушенной экономики после Гражданской войны. Новый план был направлен на увеличение советского производства с уровня, близкого к довоенному, в два с половиной раза за чуть более чем четыре года. В отсутствие иностранных инвестиций или внутреннего финансирования такой план мог быть реализован, как утверждал бывший чешский историк Михал Рейман, только путем «очень жестокого удара по условиям жизни и труда промышленных рабочих и сельского населения». Рейман предполагал, что политика Сталина 1928 года скорее являлась не хорошо спланированной стратегией, а ситуативной реакцией на очень глубокий социальный и экономический кризис конца НЭПа. По мнению Реймана, истоки сталинской социальной системы «неравенства и привилегий» и ликвидация оппозиционных сил режимом были взаимосвязаны. Реализация плана требовала «существования правящего социального слоя, отделенного от народа и враждебно настроенного по отношению к нему».

Длительная атака государства на советских крестьян и рабочих не осталась без ответа и встретила ожесточенное сопротивление. Здесь мы рассмотрим социальный кризис 1928 года с точки зрения двух оппозиционных большевистских групп: недавно исключенной (декабрь 1927 года) Объединенной оппозиции и еще более радикального течения демократических централистов. В настоящее время мы располагаем широким спектром документов, которые касаются не только внутренней жизни этих двух групп, но и отношений между ними, а также отражают проявления солидарности и взаимную критику как на уровне руководства, так и на уровне рядовых членов. Примечательно, что разрыв между лидерами двух групп продолжал углубляться в течение 1928 года, в то время как рядовые члены проявляли уважение друг к другу и даже сотрудничали на практике. Заявления, переписка и листовки дают замечательную возможность понять, как социалисты того времени воспринимали события и надеялись повлиять на события бурного года. В том тексте мы изучим, как две оппозиционные группы анализировали кризис, природу режима, и то, как рядовые члены к концу осени 1928 года стали реагировать на увеличившуюся активность рабочих, все чаще призывая единству групп.

Как отмечал Алексей Гусев на нашем последнем семинаре, децисты сыграли решающую роль как в оппозиции 1923 года, так и в формировании Объединенной оппозиции в 1926 году — особенно Тимофей Сапронов, который в начале 1926 года выступал в качестве посредника на переговорах между сторонниками Зиновьева и троцкистами. Позже в том же году децисты выступили против того, чтобы оппозиция отступила перед угрозой исключения из партии: в октябре они раскритиковали Зиновьева и Троцкого за раскаяние во «фракционности» и «нарушении партийной дисциплины» и порвали с Объединенной оппозицией. Даже сочувствующий Троцкому биограф Исаак Дойчер признал, что тактическое отступление оппозиции пошло на пользу партийному руководству. «Оппозиция … уступила так много и ничего не получила. Она отказалась от единомышленников и союзников, признала себя виновной в нарушении запрета 1921 года, призвала свою организацию к роспуску…» По его мнению, оппозиция «связала себе руки», только «чтобы подставить себя под новые удары». Но, как мы увидим, даже после этого разрыва радикальные позиции децистов продолжали пользоваться значительным вниманием среди оппозиционеров.

На протяжении 1927 года и снова в 1928 году децисты неоднократно направляли свою критику в первую очередь против Сталина, а не против бухаринцев, которые были в центре критики Троцкого и Объединенной оппозиции. Децисты утверждали в своей платформе, которая распространялась под заголовком “Под знамя Ленина”, что уже в течение нескольких лет реальная политическая власть находилась в руках Секретариата ЦК и Сталина. «Партийные массы» контролировались партийными комитетами, которые, в свою очередь, находились в руках секретарей, фактически назначаемых сверху. Аналогичный процесс происходил и в «высшем партийном исполнительном органе, Центральном комитете. Начиная с 1923 года, фактическое руководство партией постепенно переходит из рук Политбюро в руки Секретариата во главе с генсеком тов. Сталиным».

В марте 1927 года Сталин сделал очень необычное для него открытое заявление об усиливающемся наступлении на советских рабочих (его аналогичное заявление на пленуме ЦК в июле 1928 года не будет опубликовано еще в течение двадцати лет). На 5-й конференции комсомола в речи о «рационализации» Сталин утверждал, что «ни один крупный шаг в нашей стране не был сделан без определенных жертв со стороны отдельных групп рабочего класса в интересах всего рабочего класса нашей страны». Поэтому он утверждал, что «мы не должны останавливаться перед небольшими жертвами в интересах рабочего класса». Децисты, в отличие от Троцкого и Объединенной оппозиции, открыто бросили вызов этому призыву к жертвам со стороны рабочих. «Только человек, ослепленный властью, уже утративший способность понимать рабочих, может говорить так», — заявили они в своей платформе. Децисты утверждали, что «под видом борьбы с «отдельными группами рабочего класса» Сталин ведет борьбу «против рабочего класса в целом, опираясь на непролетарские классы».

В 1927 году децисты продолжали утверждать, что между Сталиным и Бухариным не было существенных различий в аграрной политике. Хотя они цитировали знаменитое заявление Бухарина 1925 года о том, что «мы должны сказать всему крестьянству, всем его слоям: обогащайтесь, накапливайте, развивайте свои хозяйства», децисты настаивали, что «было бы неверно считать, что сталинская группа в вопросах деревенской политики занимает какую-то принципиально иную, ’’левую” позицию, в противоположность откровенно правой позиции Смирнова, Калинина, Каминского». Для децистов решающее значение имела «господствующая сталинская группа» и использование ею репрессий. Они утверждали, что Сталин «прибег к явно фашистским методам борьбы, к формальному запрету дискуссий, исключению из партии, угрозам увольнения с работы и прямому преследованию». В этом вопросе они резко расходились с Объединенной оппозицией. В своей платформе они утверждали, что «вместо того, чтобы показать партии, что главным оплотом правой опасности является сталинская группа и подчиненный ей партийный аппарат» (что было позицией всей оппозиции до дискуссии 1926 года), оппозиция Зиновьева-Троцкого «неоднократно ориентировала партию на то, что сталинская группа может сама начать бороться с правой опасностью».

Практически сразу после XV съезда партии в декабре 1927 года несколько тысяч оппозиционеров были сосланы в отдаленные уголки Советского Союза. Троцкий был отправлен за 4000 километров в Алма-Ату в Казахстане: ГПУ сообщило, что его пришлось «увезти силой», а в Москве его провожала толпа из 3000 человек с криками «Долой жандармов!», « Долой термидорианцев!» и «Долой фашистов!». До октября режим слежки за ним в Алма-Ате был относительно снисходительным: Троцкий охотился, снимал дачу с яблоневым садом, ежедневно получал мешки с почтой и даже сумел наладить собственную почтовую связь из Москвы. Троцкисты и децисты были разбросаны по всему Советскому Союзу: Христиан Раковский в Барнауле; Евгений Преображенский в Сибири; Карл Радек в Тобольске, лидер децистов Тимофей Сапронов на Крайнем Севере в Шенкурске. Для Троцкого необходимость реформ внутри режима была первостепенной задачей на протяжении всего 1928 года, и он противопоставлял ее тому, что он считал ультралевыми призывами децистов к революции. В «Обращении ссыльных» в январе троцкисты категорически отрицали, что они стремились «создать вторую партию», — обвинение, которое партийные лидеры неоднократно выдвигали против них, хотя отчеты ОГПУ Сталину показывают, что они — лидеры — при этом понимали, что это не соответствует действительности. Несмотря на политические разногласия с Троцким, Сапронов пытался поддерживать с ним нормальные отношения, отправив ему поздравление с Первомаем из Шенкурска.

Чтобы понять огромные изменения, произошедшие в 1928 году, нам необходимо кратко рассмотреть корни кризиса. Экономическая катастрофа конца 1927 года потрясла советское общество и стала центральной темой дискуссий во всех кругах, хотя материалы обсуждений в советском руководстве были недоступны для членов партии и советских граждан. В 1923 году подобный кризис — «кризис ножниц», как называл его в то время Троцкий, — привел к тому, что растущие цены на производившиеся в недостаточном количестве промышленные товары все больше расходились с низкими ценами на сельскохозяйственную продукцию. К концу 1923 года цены на сельскохозяйственную продукцию составляли лишь 89% от довоенного уровня, в то время как цены на промышленные товары были почти в три раза выше довоенного уровня. Это означало, что доходы крестьян упали, и им стало трудно покупать промышленные товары: многие перестали продавать свою продукцию и вернулись к натуральному хозяйству. В 1927 году тоже наступил кризис, и к концу лета во многих городах появились очереди за продуктами, поскольку крестьяне, неспособные покупать вновь подорожавшие промтовары, начали сокращать свою товарную продукцию. Советские лидеры утверждали, что опасения населения преувеличены, но за последние два месяца года товарная продукция сократилась вдвое по сравнению с предыдущим годом — катастрофа, усугубленная неурожаем озимой пшеницы на Украине.

Кризис был настолько серьезным, что в январе 1928 года Сталин и его окружение предприняли беспрецедентный шаг, лично отправившись на Урал и в Сибирь на три недели, чтобы запугать местных лидеров и провести «чрезвычайные меры» по закупкам на «зерновом фронте». Члены Центрального комитета и 30 000 преданных ему партийных активистов разъехались по всему Советскому Союзу, вооруженные полномочиями формировать тройки по закупке зерна (комитеты из трех человек), чистить непокорные организации, арестовывать крестьян и конфисковывать имущество «спекулянтов» за умышленное уклонение от продажи зерна.

Суровые меры, принятые в начале 1928 года и направленные якобы против «кулаков» (более зажиточных крестьян), сильнее всего ударили по средним крестьянам. Как показал Моше Левин, более зажиточные крестьяне в основном продавали свое зерно по более низким ценам, принимая на себя убытки, в то время как средние крестьяне держались в надежде на более высокие цены. В Сибири Сталин резко критиковал местных чиновников как агентов «кулаков», но Левин показал (и практически все современные историки Советского Союза с этим согласны), что эта политика была направлена против всего крестьянства. «Кулаки» не были классом в марксистском понимании и не отличались значительно от других сельских жителей. Только один процент крестьян нанимал более одного рабочего, а более обеспеченные крестьяне зарабатывали всего в пять раз больше, чем самые бедные. Вместо того чтобы выражать враждебность по отношению к немного более зажиточным крестьянам, другие сельские жители были довольны тем, что те были готовы нанимать их или одалживать им деньги в то время, когда советское государство не могло этого сделать. В. П. Данилов отметил, что согласно советской переписи 1927 года средний размер земельного надела «кулаков» без учета арендуемой земли был всего в четыре раза больше, чем у бедных крестьян. Масштабы сопротивления крестьян сталинской кампании были огромны: в 1928 году произошло более 700 массовых восстаний. Позже, во время коллективизации и раскулачивания, крестьянки неоднократно помогали организовывать коллективное сопротивление миллионов людей, в тысячах деревень. Как впервые предположил Э. Х. Карр, «классовый анализ больше не определял политику»: скорее, политика определяла, «какая форма классового анализа была уместна в данной ситуации».

Абсурдность антикулацкой политики режима только усугубилась в течение следующих двух лет. Архивные исследования Линн Виолы доказали, что целые деревни неоднократно проявляли солидарность перед лицом государственного наступления: «У нас здесь нет кулаков» стало «фактическим рефреном конца 1920-х годов, неявной защитой всей деревни». Более зажиточные крестьяне понимали последствия «антикулацких» действий и риторики режима и часто бежали в города или намеренно снижали свой финансовый статус, чтобы избежать репрессий со стороны государства — в том числе миллион человек только в РСФСР. Постановлением Политбюро от января 1930 года были установлены региональные планы по раскулачиванию для высшей категории — тех, кого отправляли в концентрационные лагеря, в том числе 15 000 человек для Украины. Накануне жестокой кампании по раскулачиванию 1930 года глава правительства РСФСР Сергей Сырцов признал, что некоторые местные чиновники утверждали, что если не будет найдено достаточно кулаков, «мы получим их путем назначения». Иногда крестьяне сами выдвигали кандидатов, проводя жеребьевку, чтобы выполнить установленную режимом развёрстку по кулакам. В отчете ОГПУ от марта 1930 года признавалось, что средние крестьяне, бедные крестьяне, безземельные батраки, семьи красных партизан и солдат Красной Армии были сосланы и что такие случаи «происходили почти повсеместно…».

«Чрезвычайные меры» начала 1928 года вызвали совершенно разные реакции у Троцкого и лидера децистов Сапронова. В циркулярном письме своим сторонникам от 9 мая 1928 года Троцкий затронул вопрос о поддержке официального поворота Сталина и о том, готова ли оппозиция поддержать его. «Мы готовы, безоговорочно, всеми силами и средствами», – писал он. Он утверждал, что, хотя оппозиционеры сохранят свою независимость, этот поворот увеличит возможность реформирования партии «без больших потрясений» и что они будут содействовать этому процессу «полностью и в меру своих возможностей». Сапронов же написал из Шенкурска троцкисту Нечаеву, что из полученных им писем следует, что «мы единодушно выступаем против “левого поворота”».

В «Итогах июльского пленума» Н. Баскаков утверждал, что троцкисты неправомерно охарактеризовали сдвиг Сталина как «левый». Это был лишь «псевдолевый» маневр, который не давал «пролетарской части партии никаких оснований для переоценки чего бы то ни было». Через три месяца стало ясно, что «рабоче-крестьянский союз распался, а среди рабочих и крестьян усилились антисоветские настроения, которые в некоторых местах угрожали перерасти в восстание». По мнению Баскакова, «маневры сверху» и «реформистские компромиссы» были недостаточны, чтобы остановить или даже замедлить дальнейшее сползание: единственным решением была «мощная волна массовых протестов рабочего класса». Он настаивал, что июльский пленум ознаменовал «новую стадию капитуляции ЦК перед кулаками, более решительную и оппортунистическую, чем в четырехлетний период до XV съезда партии». Борьба за зерно «выявила беспрецедентный упадок и классовую дегенерацию партийного и советского аппарата». Хотя его аргументы не были столь крайними, как взгляды Троцкого на «кулаков», он все же утверждал, что кулаки будут «еще более нагло сопротивляться попыткам партии проводить классовую политику в сельской местности в области земельной реформы и налогообложения».

Заявление Пролетарской оппозиции (децистов) «Лицом к кулакам, спиной к рабочим» также было сосредоточено на сталинских лидерах. В нем отмечалось, что кулакам повысили цены на закупку зерна, в то время как «декреты, касающиеся бедных, не выполняются». Оно цитировало отчет Рабкрина в «Правде», который показывал, что вместо 38% бедных крестьян, которых предполагалось освободить от налогов в Московской области, только 23% были освобождены, а в некоторых деревнях этот показатель составлял всего 15%. Сталинское руководство было «политическими интриганами», потому что они «били правых», в то же время сами «проводили их линию». Призывая других рабочих «присоединиться к сопротивлению», они заявили, что «только организация и единство рабочего класса могут отразить постоянно растущее давление».

Пленум ЦК в апреле подтвердил «чрезвычайные меры» и санкционировал усиление давления на крестьян в ходе хлебозаготовок. К лету между двумя группами партийного руководства назрела конфронтация. Несмотря на публичную демонстрацию единства на июльском пленуме ЦК, раскол между Сталиным и его соратниками, с одной стороны, и бухаринцами, с другой, достиг критической точки — и подробности этого в конце концов дошли до Троцкого. 11 июля Бухарин тайно встретился с бывшим союзником Троцкого Каменевым: позже он встретился с московскими троцкистами, которые передали рассказ Каменева Троцкому в Алма-Ате.