Lenin once said: if you ditch Hegel, you derail Marx. This comes with a reminder: read your Marx or crash hard! But what to read in Marx, which Marx, when, and how? Reading Marx doubles, triples, quadruples as misreading, overreading, underreading, un-reading, Ur-reading Marx; as reading into Marx; as reading Marx into others; as reading Marx reading others. ‘Marx’ usually designates Marx and Engels as an intellectual unit and a political party; at other times, ‘Marx’ refers to a lone wolf apart from Engels. Engels, the ‘General’, for his part, inhabits several lives: Engels before Marx, alongside Marx shoulder-to-shoulder, and after Marx. Engels may have called himself a ‘second fiddle’ next to Marx, but he was more than a reader, editor and sponsor of Marx. He was a theoretician, tactician and adventurer in his own right. The two comrades in arms authored what fills their archives, and, by silence, what never made it in. Yet the fate of that legacy is scarcely theirs to decide alone.

Archives, editors, and their selections largely shape how Marx and Engels come down to us.[1] At first glance, what survives in the archive is what is stubbornly present in manuscripts, drafts, letters and notebooks. On closer inspection, the archive determines what endures, what is catalogued, and what even counts as archival material. Tautologically, an archive is what the archive archives. But deadly seriously, an archive is where what counts as history is decided, framed, and laid before us. ‘Marx’ and ‘Engels’, or indeed ‘Marx and Engels’, as we know them and as they are introduced to us, are no exception.[2]

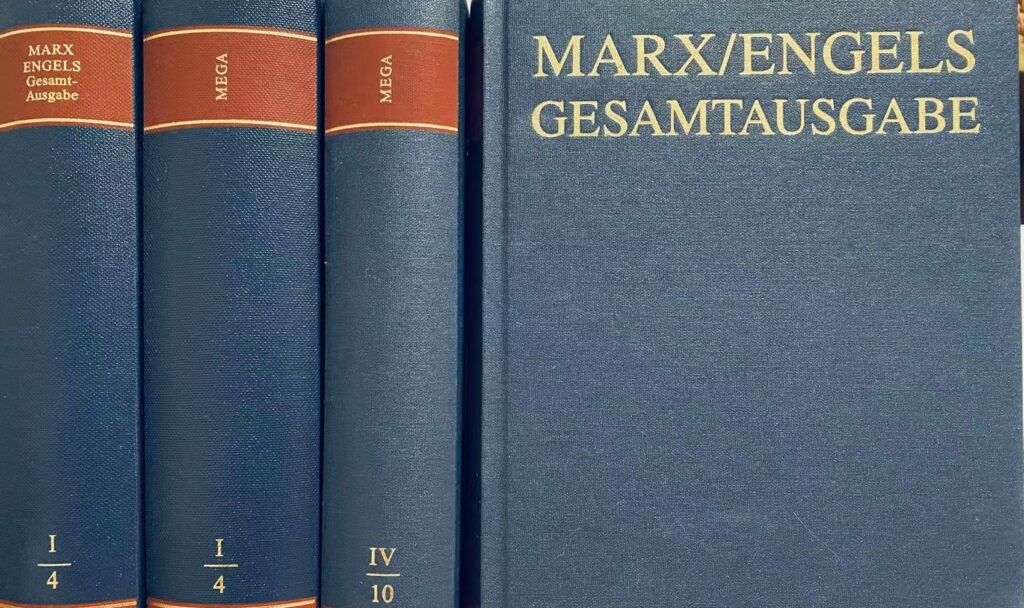

MEGA – the greatest pun of all history – stands for ‘(make) Marx-Engels-Great-Again!’. In German, it is somewhat less fancy: Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe. Still, it comes surprisingly close to Gesamtkunstwerk. Put Sartre’s totalisation and Jameson’s historicisation in the same room, and you arrive at something that resembles the spirit of the Gesamtausgabe. MEGA is, in every sense, a mega-project, driven by mega-ambitions to produce the historical-critical edition of Marxism’s two mega-figures. For all the sublimity on display in its title, the project’s political and historical backstory is far more humble, even meagre in places. It is forged in sweat, blood and archival dust.

Before MEGA

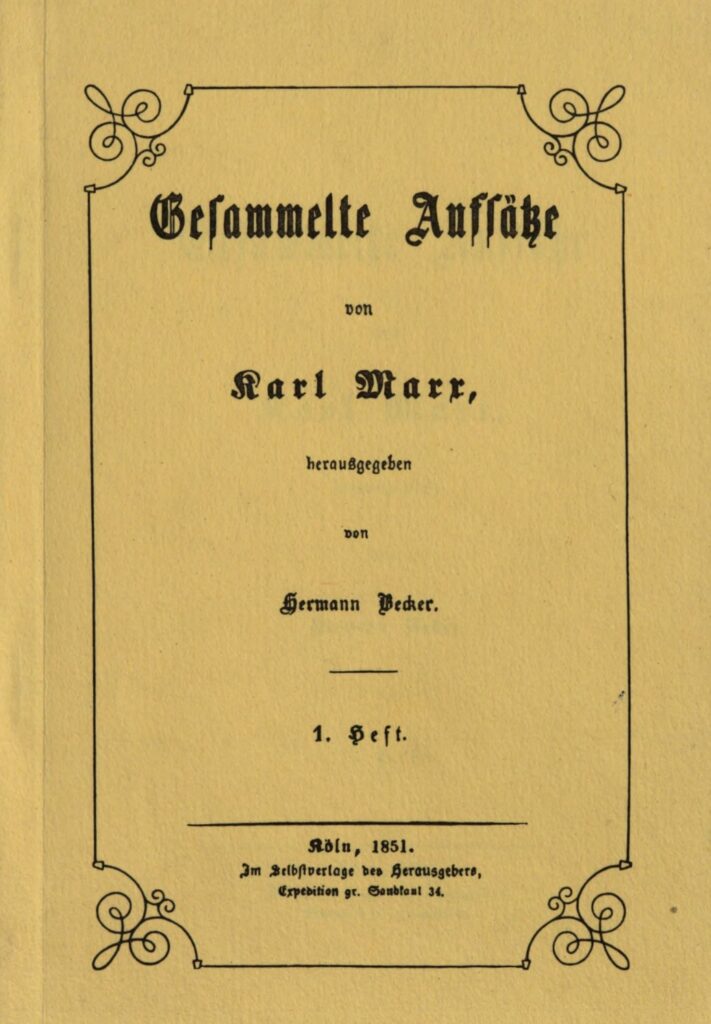

Long before any collected edition of Marx and Engels appeared, Marx witnessed the beginnings of a selected edition of his own works. In November 1850, he laid out the plan and reconnected with the Cologne publisher Hermann Becker. Supported by the Communist League, a two-volume project aimed to gather his pre- and post-1848 writings, including newspaper articles and a German translation of his Poverty of Philosophy. Technical problems, financial troubles, and police harassment slowed production, so only the first instalment appeared in 1851. Political repression and Becker’s arrest prevented the project from continuing and later attempts to secure another publisher through Ferdinand Lassalle failed.[3]

Where Marx in the early 1850s could only glimpse his writings gathered in a modest selection, Engels imagined a far grander compendium: a complete edition of Marx’s works, arranged chronologically, each text preserved in its historical form, cleaned of textual errors, and framed with prefaces and explanatory footnotes to guide the reader. Yet, as custodian of Marx’s legacy, Engels found himself buried beneath the herculean task of editing the second (1885) and third (1894) volumes of Capital. He was unable to mount the full exhibition he envisioned. In his lifetime, he allowed the SPD only occasional glimpses, printing a few minor works in isolation without commentary or introduction so as not to scatter the collection before its appointed unveiling. Still, he took quiet pleasure in seeing apprentices like Eduard Bernstein eager to decipher the ‘hieroglyphics’ of Marx’s texts. Kautsky was likewise drafted into the line of succession.[4]

After Engels died in 1895, the SPD gradually assumed guardianship of the Marx–Engels legacy and began prying open its sealed drawers. Franz Mehring’s Nachlass edition of 1902 exposed long-lost writings from the 1840s. Kautsky’s Theories of Surplus Value (1905–10) carried on the slow excavation of Marx’s manuscripts. In 1910/11, some leading Austro-Marxists and the Russian archivist David Riazanov agreed that, once copyright lapsed in 1913, the SPD should produce a definitive, fully scholarly edition of Marx’s works. Yet the project immediately collided with party politics.[5] The 1913 Briefwechsel (correspondence), edited by Bernstein and August Bebel, revealed how fears of embarrassing allies could trump editorial completeness, resulting in an abridged and selective publication.[6] Kautsky’s 1914 ‘popular’ edition of Capital and Riazanov’s 1917 two-volume selection added a few more windows into the archive, but only a fraction of the estate was brought to light.

MEGA1

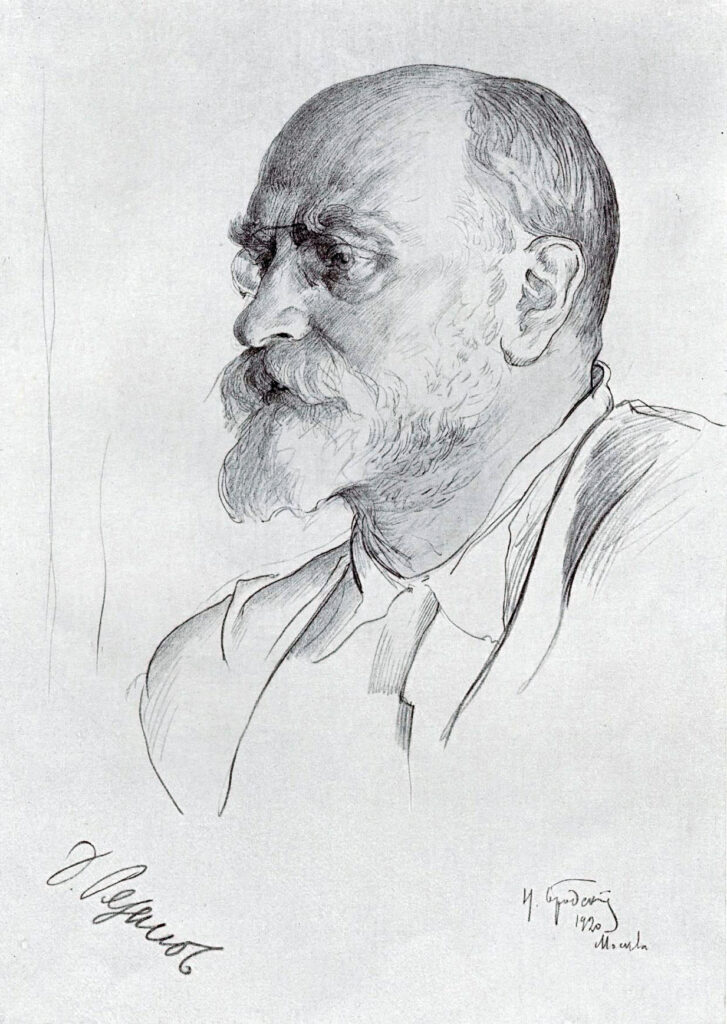

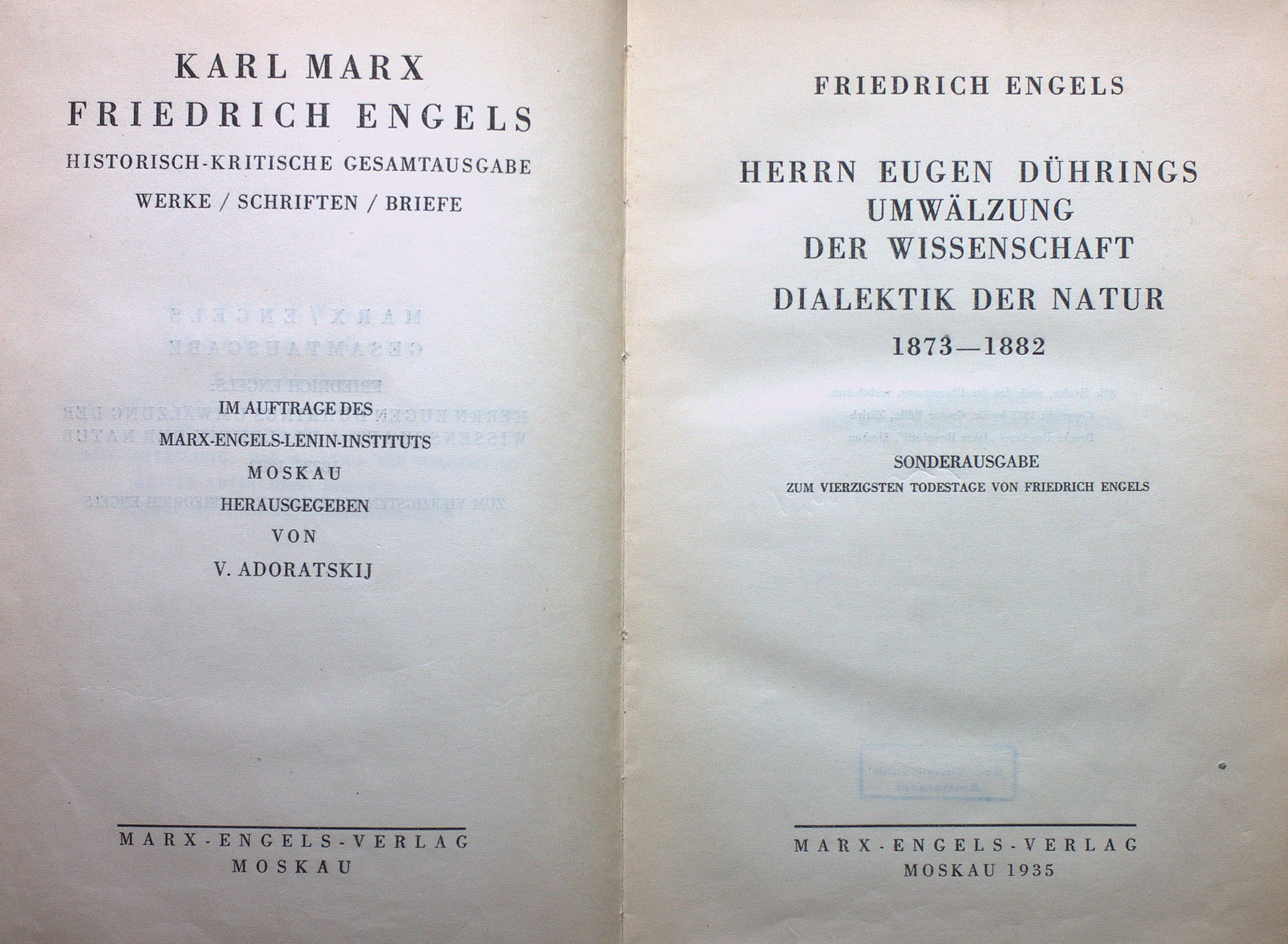

The first MEGA (MEGA1) came into existence in the early Soviet Union. Approved by the Comintern in 1924 and housed first in the Marx–Engels Institute and later in the Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute, the project was directly tied to the Soviet state even while relying on international cooperation, especially with the SPD, whose Berlin archive contained most of the legacy.[7] Riazanov, authorised in 1921 to hire non-party specialists, drove the effort.[8] He drew on his long ties to the SPD, photographed manuscripts, and organised a Europe-wide network to gather documents and channel them to Moscow.[9] Agreements with the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt and a Berlin-based publishing society allowed work on a planned 42-volume edition to begin. Between 1927 and 1941, twelve volumes appeared, including major first editions such as the 1844 Manuscripts, The German Ideology, Dialectics of Nature, and the 1939 publication of the Grundrisse.[10]

Riazanov fought to keep the edition alive under heavy political pressure, insisting on a measure of autonomy for himself and the institute. This brought escalating conflict and ended with his 1931 arrest on Stalin’s orders and, like some other leading MEGA1 editors, his eventual tragic death in the purges.[11] Vladimir Adoratsky, appointed as director of the now Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute, initially tried to continue MEGA1 by adjusting its prefaces to the doctrinal line. The Soviet publishing cooperative for foreign workers in the USSR issued seven further volumes by 1935. The last, a joint edition of Anti-Dühring and Dialectics of Nature, appeared disguised as a special Engels memorial volume. MEGA1 came to an end after successive waves of purges and, ultimately, the outbreak of the Second World War.[12]

MEGA²

The MEGA² project was launched as a bold attempt to rebuild the Marx–Engels edition from the ground up. After a major 1967 reassessment of new German editorial scholarship, and exchanges with fellow editors, the Berlin Marx–Engels department developed a new MEGA concept, pushing it through despite considerable misunderstandings and resistance.[13] The International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam (holder of two-thirds of the original Marx–Engels manuscripts) then agreed to support the project once its historical-critical character was secured and it became clear that only such an institution could realise an undertaking of this scale. The editorial guidelines published for public discussion in 1972 drew on innovative approaches and were widely welcomed; over 120 experts noted that they advanced the field and would shape future editorial practice.[14]

The demise of the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc states nearly capsized the MEGA² project, yet they also opened doors no one had imagined. For a while, no one knew whether Marx and Engels would be shelved, restarted from scratch, or carried forward with the hard-won materials already in hand. In the end, despite old anxieties about the political legacy of Marx and Engels, German science policymakers chose the pragmatic middle course. With the creation of the International Marx–Engels Foundation in 1990, MEGA² was relaunched as a strictly academic venture, internationally steered and politically unencumbered. Updated guidelines, digital tools, and a streamlined plan of 114 volumes gave the project its modern shape. Folded into Germany’s Academies Programme, MEGA² finally found a stable institutional home, and a future.[15]

MEGA Dossier

If MEGA teaches one hard truth, it is that ‘Marx’ and ‘Engels’ refuse to sit still. They morph whenever an archive creaks open or a translation tilts the ground beneath them. This dossier takes that lesson to heart. It is a workshop in motion, a MEGA-in-miniature forever under construction. We gather new translations, revisit old ones, track what MEGA has unearthed, and invite reflections on how Marx and Engels travel across languages, centuries, and political climates. Think of it as a living reading room where the shelves keep shifting and the texts keep talking back.

Literature

Backhaus, Hans-Georg and Helmut Reichelt 1995, ‘Der politisch-ideologische Grundcharakter der Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe: eine Kritik der Editionsrichtlinien der IMES’, MEGA-Studien, 1994/2: 101-118.

Dlubek, Rolf 1992, ‘Frühe Initiativen zur Vorbereitung einer neuen MEGA (1955-1958)’, Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-Forschung. Neue Folge 1992, Berlin: Argument.

Dlubek, Rolf 1993, ‘Tatsachen und Dokumente aus einem unbekannten Abschnitt der Vorgeschichte der MEGA (1961-1965)’, Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-Forschung. Neue Folge 1993, Berlin: Argument.

[Editors] 1977, ‘Karl Marx. Gesammelte Aufsätze. Februar 1851. Entstehung und Überlieferung’, in Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA2), section I, volume 10, Berlin: Dietz.

Engels, Frederick 2001a, ‘Engels to Karl Kautsky. 29 June 1891’, in Marx-Engels Collected Works, vol. 49, London: Lawrence & Wishart, pp. 209-212.

Engels, Frederick 2001b, ‘Engels to Karl Kautsky. 28 January 1889’, in Marx-Engels Collected Works, vol. 48, London: Lawrence & Wishart, pp. 257-9.

Hecker, Rolf 1997, ‘Rjazanov’s Editionsprinzipien der ersten MEGA’, Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-For schung Neue Folge. Sonderband 1, Hamburg: Argument.

Hecker, Rolf, Richard Sperl und Carl-Erich Vollgraf (eds.) 2021, Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-Forschung. Neue Folge Sonderband 6 Boris Ivanovič Nikolaevskij Auf den Spuren des Marx-Engels-Nachlasses und des Archivs der russischen Sozialdemokratie (1922–1940), Hamburg: Argument.

Heinrich, Michael 1996, ‘Edition und Interpretation: Zu dem Artikel von Hans-Georg Backhaus und Helmut Reichelt, “Der politisch-ideologische Grundcharakter der Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe”’, MEGA-Studien, 1995/2: 111-121.

Kangal, Kaan 2018, ‘Karl Schmückle and Western Marxism’, Revolutionary Russia, 31 (1): 67-85.

Marx, Karl 1851, Gesammelte Aufsätze. 1. Heft, edited by Hermann Becker, Cologne: [Private Edition].

Rjasanow, David Borisowitsch 2007 [1927], ‘Vorwort zur MEGA 1927’, UTOPIE kreativ, 206: 1095–1011.

Rokitianskii, Iakov and Reinkhard Miuller 1996, Krasnyi dissident. Akademik Riazanov ‒ opponent Lenina, zhertva Stalina. Biograficheskii ocherk. Dokumenty. Moscow: Academia.

Rokitjanskij, Jakov 1993, ‘Das tragische Schicksal von David Borisovic Rjazanov’. Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-Forschung. Neue Folge 1993, Hamburg: Argument.

Schiller, Franz 1930, ‘Das Marx-Engels-Institut in Moskau’, Archiv für die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der Arbeiterbewegung, XV: 416–435.

Sperl, Richard 2004, „Edition auf hohem Niveau“. Zu den Grundsätzen der Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA), Hamburg: Argument.

Sperl, Richard 2005, ‘Marx-Engels-Editionen’, in Bodo Plachta (ed.), Editionen zu deutschsprachigen Autoren als Spiegel der Editionsgeschichte, Berlin: de Gruyter.

Vilar, Pierre 1973, ‘Marxist History, a History in the Making: Towards a Dialogue with Althusser’, New Left Review, I/80 (July/Aug): 65-106.

Vollgraf, Carl-Erich, Richard Sperl and Rolf Hecker (eds.) 2005, Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-Forschung. Neue Folge Sonderband 5 Die Marx-Engels-Werkausgaben in der UdSSR und DDR (1945–1968), Hamburg: Argument.

[1] Whatever its accuracy, Pierre Vilar (1973, p. 68) raises a point that speaks directly to this issue: ‘Not only for “Marxology” but for epistemology too, and for history above all, it is a pity that almost all editions of Marx isolate his works from each other, upset their chronology, or distinguish between their contents and the “genres” to which they belong (the “economic”, “political”, “philosophical” works, etc).’ On the question concerning the principle of chronology in MEGA, see Sperl 2004, pp. 53-67.

[2] Concerning the ideological background of the collected works of Marx and Engels in MEGA, see the debate between Hans-Georg Backhaus and Helmut Reichelt (1995), on one side, and Michael Heinrich (1996), on the other.

[3] [Editors] 1977, pp. 1020-3.

[4] Cf. Engels 2001a, p. 210; Engels 2001b, pp. 258-9.

[5] Cf. Rjasanow 2007 [1927], pp. 1100–1101.

[6] Rjasanow 2007 [1927], p. 1103.

[7] Rjasanow 2007 [1927], pp. 1096, 1110.

[8] Rokitianskii and Miuller 1996, p. 58; Rokitjanskij 1993, p. 4; Schiller 1930, p. 420.

[9] Cf. Hecker, Sperl and Vollgraf (eds.) 2021.

[10] Cf. Rokitjanskij 1993; Hecker 1997.

[11] Cf. Karl Schmückle is another significant case. Cf. Kangal 2018.

[12] Sperl 2005, pp. 336-7.

[13] For the period prior to this date, see Dlubek 1992; Dlubek 1993; Vollgraf, Sperl and Hecker (eds.) 2005.

[14] Sperl 2005, p. 342.

[15] Sperl 2005, pp. 344-5.